Semi-cursive script

| Semi-cursive script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | Han dynasty to present |

| Languages | Old Chinese, Middle Chinese, Modern Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, Korean |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Oracle bone script

|

Child systems | Regular script Zhuyin Simplified Chinese Chu Nom Khitan script Jurchen script Tangut script |

| Unicode | |

| 4E00–9FFF, 3400–4DBF, 20000–2A6DF, 2A700–2B734, 2F00–2FDF, F900–FAFF | |

| Semi-cursive script | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

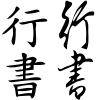

Traditional characters for "semi-cursive script" written in regular script (left) and semi-cursive script (right). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 行書 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 行书 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | walking/running script[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | hành thư chữ hành | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 行書 𡨸行 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 행서 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 行書 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 行書 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ぎょうしょ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Semi-cursive script (traditional Chinese: 行書; simplified Chinese: 行书; pinyin: xíngshū), also known as running hand script, is a style of calligraphy which emerged in China during the Han dynasty (3rd century BC – 3rd century AD). The style is used to write Chinese characters and is abbreviated slightly where a character’s strokes are permitted to be visibly connected as the writer writes, but not to the extent of the cursive style.[2] This makes the style easily readable by readers who can read regular script and quickly writable by calligraphers who require ideas to be written down quickly.[2] In order to produce legible work using the semi-cursive style, a series of writing conventions is followed, including the linking of the strokes, simplification and merging strokes, adjustments to stroke order and the distribution of text of the work.[3]

One of the most notable calligraphers who used this style was Wang Xizhi, known for his work Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection (Lantingji Xu), produced in AD 353. This work remains highly influential in China, as well as outside of China where calligraphy using Chinese characters are still in practice, such as Japan and Korea.[3] In modern times, semi-cursive script is the most prominent in Chinese daily life despite a lack of official education offered for it, having gained this status with the introduction of fountain pens, and there have been proposals to allow for customizable fonts on computers.

History

The Chinese writing system has been borrowed and used in East Asian countries, including Japan, Korea and Vietnam for thousands of years due to China’s extensive influence, technology and large territory. As a result, the culture of calligraphy and its various styles spread across the region, including semi-cursive script.[3][4]

China

The semi-cursive style was developed in the Han Dynasty.[2] Script in this style is written in a more curvaceous style than the regular script, however not as illegible as the cursive script.[1]

One of the most notable calligraphers to produce work using the semi-cursive style is Wang Xizhi, where his work Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection was written in 353 AD.[3] The work included the character 之, a possessive particle, twenty-one times all in different forms. The difference in form was generated by Wang under the influence of having alcohol with his acquaintances. He had wanted to reproduce the work again since it was in his liking, but to no avail. Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Collection is still included in some of the world’s most notable calligraphy works and remains highly influential in the calligraphy world.[3]

The semi-cursive style was also the basis of the techniques used to write with the fountain pen when Western influence was heavy in China, in the early 20th century. Although it is not officially taught to students, the style has proceeded to become the most popular Chinese script in modern times.[3][5] In the digital age, it has been proposed to encode Chinese characters using the "track and point set" method, which allows users to make their own personalized semi-cursive fonts.[5]

Japan

Calligraphy culture from China was introduced to Japan in around AD 600 and has been practiced up to the modern day. Although Japan originally used Chinese characters (called kanji in Japanese) to represent words of the spoken language, there were still parts of the spoken language that could not be written using Chinese characters.[1] The phonetic writing systems, hiragana and katakana, were developed as a result of the semi-cursive and cursive styles.[1] During the Heian Period, a large number of calligraphy works were written in the semi-cursive style because the roundedness of the style allowed for a natural flow between kanji and hiragana.[6][7] In the Edo period, general trends have been noticed where semi-cursive was used with hiragana in mixed script for "native" literature and books translated for commoners, while regular script kanji was used alongside katakana for Classical Chinese works meant to be read by scholars.[8]

Korea

Chinese calligraphy appeared in Korea at around 2nd or 3rd century AD. Korea also used Chinese characters (called hanja in Korean) until the invention of the Korean alphabet, hangul, in 1443.[9] Even then, many calligraphers did not choose to use the newly created hangul writing system and continued to write calligraphy and its various styles using Chinese characters.[10] In this environment, semi cursive script started seeing use in Korea during the Joseon Dynasty.[11][12]

Characteristics

Semi-cursive script aims for an informal, natural movement from one stroke to the next.[2] Another distinct feature of this style is being able to pinpoint where each stroke originates and which stroke is it followed by. In order to be able to write in the semi-cursive style, the calligrapher should be able to write in the regular script and know the order the strokes should be written in.[1]

Many calligraphers choose to use this style when they need to write things down quickly, but still require the characters to be readable. In Japan, most calligraphy works are done in this style due to its ability to create a style unique to the calligrapher in a small timeframe.[1]

Uses

The semi-cursive style is practiced for aesthetic purposes, and a calligrapher may choose to specialize in any script of their preference. The smooth transition and omission of some strokes of the semi-cursive style had also contributed to the simplification of Chinese characters by the People's Republic of China.[4]

Writing conventions

Stroke linking

One of the characteristics of semi-cursive script is the joining of consecutive strokes. To execute this, one must write a character in an uninterrupted manner and only stop the brush movement when required. In some scenarios, the strokes may not be visibly linked, but it is possible to grasp the direction which each stroke is drawn.[3]

Stroke merging and character simplification

The fast brush movement needed for the semi-cursive style allows a decrease in the number of strokes needed to produce a character. However, this is done in a way to preserve readability by considering the stroke order of each Chinese character in most cases. There are no solid rules to the way in which characters are simplified, and it is up to the calligrapher to display their personal style and preferences.[3]

Stroke order modification

With the intention to prioritise speed, calligraphers may choose to make subtle changes to the stroke order of the written character. They may choose to reverse the direction of the stroke or write the strokes out of order compared to how they are written in the regular script.[3]

Text direction

In works written using semi-cursive script, the size of each character can vary greatly with each other. Where works of the regular script are usually written in the same size, semi-cursive characters can be arranged to achieve “rhythm and balance” artistically. To preserve this rhythm and balance, most semi-cursive and cursive works are written in vertical columns from right to left, despite the adoption of the Western standard in Chinese texts, writing in rows from left to right.[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Sato, Shozo (2014). Shodo: The quiet art of Japanese Zen calligraphy. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1204-9. OCLC 1183131287.

- ^ a b c d "5 script styles in Chinese Calligraphy". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Li, Wendan (2010-05-31). Chinese Writing and Calligraphy. University of Hawaii Press. doi:10.1515/9780824860691. ISBN 978-0-8248-6069-1.

- ^ a b Li, Yu (2020). The Chinese writing system in Asia: An interdisciplinary perspective. London. ISBN 978-1-000-69906-7. OCLC 1114273437.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Wu, Yao; Jiang, Jie; Li, Yi (December 2018). "A Method of Chinese Characters Changing from Regular Script to Semi-Cursive Scrip Described by Track and Point Set". 2018 International Joint Conference on Information, Media and Engineering (ICIME). IEEE. pp. 162–167. doi:10.1109/icime.2018.00041. ISBN 978-1-5386-7616-5. S2CID 58012641.

- ^ Bernard, Kyoko; Nakata, Yujiro; Woodhill, Alan; Nikovskis, Armis (1973). "The Art of Japanese Calligraphy". Monumenta Nipponica. 28 (4): 514. doi:10.2307/2383576. ISSN 0027-0741. JSTOR 2383576.

- ^ Boudonnat, Louise (2003). Traces of the brush: The art of Japanese calligraphy. Harumi Kushizaki. San Francisco: Chronicle. ISBN 2-02-059342-4. OCLC 51553636.

- ^ Hisada, Yukio (2018-03-31). "The Usage of Sentences Mixing Regular-Script Kanji and Hiragana in the Latter Part of the Edo Period". グローバル日本研究クラスター報告書. Vol. 1. Osaka University. pp. 170–180.

- ^ Choi, Yearn-hong (2016). "Choe Chi-won, great Tang and Silla poet". The Korean Times. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Brown, Ju (2006). China, Japan, Korea: Culture and customs. John Brown. North Charleston, South Carolina: BookSurge. ISBN 1-4196-4893-4. OCLC 162136010.

- ^ "Categories of calligraphy". swmuseum.suwon.go.kr. Retrieved 2021-07-30.

- ^ "Collection of Calligraphic Works by Successive Kings from Seonjo to Sukjong – Kings of Joseon (Seonjo~Sukjong)". Jangseogak. Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2021-07-30 – via Google Arts & Culture.

Further reading

- Running Hand at chinaculture.org, Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China

External links

Media related to Semi-cursive script at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Semi-cursive script at Wikimedia Commons