Iyer: Difference between revisions

changes |

m Reverted 1 edit by 122.162.235.66 identified as vandalism to last revision by Ravichandar84. (TW) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Ethnic group |

|||

|image = [[Image:Chembai.jpg|thumb|center|[[Chembai|Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavathar]], a prominent Iyer vocalist]] |

|||

|group = Iyer |

|||

|poptime = <p align="justify">[[1901]]:415,931<ref name="ghuryep393" /><br>[[2004]]:< 2,400,000 (Estimated)<ref name="pop">{{cite journal | author=Sreenivasarao Vepachedu| title=Brahmins| journal=Mana Sanskriti (Our Culture)| year=2003| issue=69| url=http://www.vedah.net/manasanskriti/Brahmins.html#Brahmin_Population}}</ref><ref>Accurate statistics on the population of Iyers are unavailable. This is due to the fact that the practice of conducting caste-based population census have been stopped since independence. The statistics given here are mainly based on estimates from unofficial sources</ref> |

|||

|popplace = Indian states of [[Tamil Nadu]], [[Kerala]] and [[Andhra Pradesh]]|langs = [[Mother tongue]] is [[Brahmin Tamil|Tamil]] with unique Iyer dialects. Knowledge of [[Sanskrit]] for religious reasons. |

|||

|rels = [[Hinduism]] |

|||

|related = [[Panch-Dravida|Pancha-Dravida Brahmins]], [[Tamil people]], [[Iyengar]], [[Madhwa]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Iyer''' ([[Tamil language|Tamil]] : அய்யர் [[Malayalam Language|Malayalam]]:അയ്യര) also called '''Sastri'''<ref name="britannica">{{cite book | title=Encyclopedia Britannica, śāstrī | url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/524792/sastri#tab=active~checked%2Citems~checked&title=%C5%9B%C4%81str%C4%AB%20--%20Britannica%20Online%20Encyclopedia}}</ref>, '''Sarma''' or '''Bhattar'''<ref name="castesandtribes_p354">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 354</ref><ref name="permaul_p300">[[#Cochin, Its past and present|Cochin, Its past and present]], Pg 300</ref> is the name given to [[Hindu]] [[Brahmins]] of [[Tamil people|Tamil]] or [[Telugu people|Telugu]] origin who are followers of the ''[[Advaita Vedanta|Advaita]]'' philosophy propounded by [[Adi Shankara]].<ref name="Uttarakhand_info">{{Cite web|url=http://www.4dham.com/go2/Iyer.html|title=Iyer|accessdate=2008-08-07|publisher=Uttarakhand Information Centre}}</ref><ref name="imperial_gazetteer_p267">{{cite book | title=The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume XVI| last=| first=| year=1908| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=London}}, Pg 267</ref><ref name="universalhistory_1781_109">[[#universalhistory_1781|An Universal History]], Pg 109</ref><ref name="universalhistory_1781_110">[[#universalhistory_1781|An Universal History]], Pg 110</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p269">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 269</ref><ref name="folktalesofsouthernindiap3">[[#Folk Tales of Southern India|Folk Tales of Southern India]], Pg 3</ref>They are found mostly in Tamil Nadu as they are generally native to the Tamil country. But they are also found in significant numbers in Andhra Pradesh, Kerala and Karnataka. |

|||

The name 'Iyer' originated in the medieval period when different sects of Brahmins residing in the then Tamil country organized themselves as a single community. A breakaway sect of Sri Vaishnavas later formed a new community called "Iyengars".<ref name="castesandtribes_p334">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 334</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p348">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 348</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p349">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 349</ref> |

|||

Iyers fall under the [[Brahmin communities#Pancha-Dravida|Pancha Dravida Brahmin]] sub-classification of India's Brahmin community and follow the same customs and traditions as other Brahmins.<ref name="castesandtribes_p268">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 268</ref> In recent times, they have been affected by [[Reservation_in_India#Caste_Based_Reservations_in_Tamil_Nadu|reservation policies]] <ref name="Tambram"> {{cite news | last=Vishwanath | first=Rohit | title= BRIEF CASE: Tambram's Grouse | date=[[June 23]], [[2007]] | url =http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/Tambrams_Grouse/articleshow/2142389.cms | work =The Times of India | accessdate = 2008-08-19}}</ref>and the [[Self-Respect Movement]] in the Indian state of [[Tamil Nadu]]. |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

Iyers are [[South India]]n Brahmins who reside in the states of [[Tamil Nadu]], [[Kerala]], [[Andhra Pradesh]] and [[Karnataka]]. Iyers are predominantly [[Smartism|Smarthas]] or followers of the [[Smriti]] texts.<ref name="Maharashtra">{{cite book | title=Maharashtra| last=Suresh Singh| first=Kumar| coauthors=B. V. Bhanu, B. R. Bhatnagar, D. K. Bose, V. S. Kulkarni, J. Sreenath| year=2004| pages=1873| publisher=Popular Prakashan| id=ISBN 8179911020}}</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p269" /> |

|||

The term Iyer is derived from the term Ayya which is often used by Tamils to designate respectable people. There are number of etymologies for the word Ayya, generally it is thought to be derived from [[Proto-Dravidian]] term denoting an elder brother. It is used in that meaning in [[Tamil language|Tamil]], [[Telugu]] and [[Malayalam]].<ref name="tamilsinsrilankap374">{{cite book | title=The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE| last=Indrapala| first=K.| pages=374| year=2007| publisher=Vijitha Yapa| id=ISBN 978-955-1266-72-1}}</ref> Yet others derive the |

|||

word Ayya as a [[Prakrit]] version of the Sanskrit word '[[Arya]]' which means '[[noble]]'.<ref name="Ayya_etymology">{{Cite web|url=http://starling.rinet.ru/cgi-bin/response.cgi?single=1&basename=\data\drav\sdret&text_recno=175&root=config|title=The ''Ayya''|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=STarling Database|author=}} |

|||

</ref><ref name="Kerala Iyers">{{Cite web|url=http://www.keralaiyers.com/history?PHPSESSID=4935ec87b8f426ff0233383ea3ad5de3|title=History of Kerala Iyers|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=keralaiyers.com}} |

|||

</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.hinduwebsite.com/hinduism/concepts/arya.asp|title=The Concepts of Hinduism - Arya|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=hinduwebsite.com|author=V. Jayaram}} |

|||

</ref> "Ayar" is also the name of a [[Konar|Tamil Yadava]] sub-caste.<ref name="castesandtribes_p63">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 63</ref> During the [[British Raj]], Christian clergymen were also occasionally given the honorific surname "Ayyar".<ref name="castesandtribes_p19">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 19</ref> |

|||

In ancient times, Iyers were also called '''Anthanar'''<ref name="anthanar_meaning1">{{cite book | title=Educational System of the Ancient Tamils| last=Pillai| first=Jaya Kothai| year=1972| pages=54| publisher=South India Saiva Siddhanta Works Pub. Society| location=Tinnevelly}}</ref><ref name="anthanar_meaning2">{{cite book | title=Tales and poems of South India| last=Robinson| first=Edward Jewitt| year=1885| pages=67| publisher=T. Woolmer}}</ref> or '''Parpaan'''<ref name="parppan_meaning1">{{cite book | title=Naccinarkkiniyar's Conception of Phonology| url=http://books.google.co.in/books?id=moUOAAAAYAAJ&lr=&pgis=1| last=Caṇmukam| first=Ce. Vai.| year=1967| pages=212| publisher=Annamalai University}}</ref><ref name="parppan_meaning2">{{cite book | title=The Journal [afterw.] The Madras journal of literature and science, ed. by J.C. Morris| year=1880| pages=90| publisher=Madras Literary Society}}</ref><ref name="parppan_meaning3">{{cite book | title=The Eight Anthologies: A Study in Early Tamil Literature| last=Marr| first=John Ralston| year=1985| pages=114| publisher=Institute of Asian Studies}}</ref>, though the usage of the word ''parpaan'' is considered derogatory in modern times.<ref name="parppan_modernusage">{{cite book | title=The Asiatic Review| last=East India Asssociation| year=1914| pages=457| publisher=Westminster Chamber}}</ref> Until recent times, Kerala Iyers were called '''Pattars'''.<ref name="bhattar1">{{cite book | title=A Collection of Treaties, Engagements, and Other Papers of Importance Relating to British Affairs in Malabar| last=Logan| first=William| date=1989| pages=154| publisher=Asian Educational Services| id=ISBN 8120604490, ISBN 9788120604490}}</ref> Like the term ''parppan'', the word "Pattar" too is considered derogatory. |

|||

It has also been recorded that in the past, the Nayak kings of Madurai have held the title "Aiyar" while Brahmins have borne titles as Pillai or Mudali.<ref name = "castesandtribesofsouthernindia6p368">{{cite book | title=Castes and Tribes of Southern India Volume VI| last=Thurston| first=Edgar| authorlink= Edgar Thurston|coauthors=K. Rangachari| year=1909| pages=368|publisher=Government Press| location=Madras}}</ref> |

|||

== Origin == |

|||

=== Regional origin === |

|||

The origin of Iyers, like other South-Indian Brahmin communities, is shrouded in mystery. There have been evidences of Brahmin presence in the southern states even prior to the [[Sangam period|Sangam Age]]. However, it is generally believed that they were few in number and that most Iyers migrated from other parts of India at a later stage. According to some sources, these early inhabitants comprised mostly of [[priests]] who ministered in temples known as "[[Gurukkal Brahmins|Gurukkals]]". Large scale migrations are generally believed to have occurred between 200 and 1600 AD and most Iyers are believed to have descended from these migrants.<ref name="Gurukkal">{{Cite web|url=http://www.chennaionline.com/columns/DownMemoryLane/diary169.asp|title=The Brahmins of South India - Ayyars|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=chennaionline.com|author=Chander Kanta Gariyali, I. A. S}} |

|||

</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://tamilartsacademy.com/journals/volume3/articles/Vedas%20and%20Vedic%20Saivas%20in%20TN.html|title=Nataraja and Vedic concepts as revealed by Sekkilar|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=Tamil Arts Academy|author=R. Nagaswamy}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.chennaionline.com/columns/DownMemoryLane/diary172.asp|title=Dikshitars|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=chennaionline.com|author=Chander Kanta Gariyali, I. A. S}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author=K. D. Abhyankar| title=Folklore and Astronomy: Agastya a sage and a star| journal=Current Science| year=2005| volume=29| issue=12| url=http://www.iisc.ernet.in/currsci/dec252005/2174.pdf}}</ref><ref name="ghuryep360">[[#G. S. Ghurye|G. S. Ghurye]], p 360</ref>. However, this theory has come under attack in recent times from historians and anthropologists who question the validity of this theory due to lack of evidence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://micheldanino.voiceofdharma.com/tamilculture.html|title=Vedic Roots of Early Tamil Culture|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=Voice of Dharma|author=Michael Danino}}</ref><ref>[{{Cite web|url=http://koenraadelst.bharatvani.org/articles/aid/aryanpolitics.html|title=The Politics of the Aryan Invasion Debate|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=Voice of India|year=2003|author=Dr. Koenraad Elst}}</ref><ref name="Manickam">P.V.Manickam Naicker, writes in 'The Tamil Alphabet and its Mystic Aspect', 1917,Pg 74-75: "Even should Dutt's description of the aryanisation be true, the real Aryan ''corpus'' in South-India came to nothing. A ''cranial study'' of the various classes will also confirm the same. The lecturer, being a non-Brahmin, wishes to leave nothing to be misunderstood. His best and tried friends are mostly Brahmins and he is a sincere admirer of them. There is no denying the fact that the ancestors of the present Brahmins were the most cultured among the South-Indians at the time the said Aryanisation took place and got crystallized into a class revered by the people. As the cultured sons of the common mother Tamil, is it not their legitimate duty to own their kinsmen and to cooperate and uplift their less lucky brethern, if they have real patriotism for the welfare of the country? On the contrary, the general disposition of many a Brahmin is to disown his kinship with the rest of the Tamil brethern, to disown his very mother Tamil and to comstruct an imaginary untainted Aryan pedigree as if the Aryan alone is heaven-born</ref><ref name="slaterp158">[[#Slater|Slater]], Pg 158</ref> |

|||

<ref name="zvelebil_companionp260">[[#Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature|Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature]],Pg 260</ref> |

|||

During the early medieval period, when [[Ramanuja]] founded [[Vaishnavism]] many Iyers adopted the new philosophical affiliation and were called [[Iyengars]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.salagram.net/parishad6.htm|title=Sripada Ramanujacharya|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=New Zealand Hare Krishna Spiritual Resource Network}}</ref>The Valluvars are believed to be the descendants of the earliest priests of the Tamil country.<ref name = "castesandtribesofsouthernindia7p303">{{cite book | title=Castes and Tribes of Southern India Volume VII| last=Thurston| first=Edgar| authorlink= Edgar Thurston|coauthors=K. Rangachari| year=1909| pages=303|publisher=Government Press| location=Madras}}</ref> |

|||

There is also ample evidence to suggest that a large number of individuals of non-Brahmin communities could have been invested with the sacred thread and ordained as temple priests.<ref name="castesandtribes_lii">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Introduction, Pg lii</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_liv">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Introduction, Pg liv</ref> |

|||

Though, Iyers have been classified as a left-hand caste in ancient times,<ref name="ghuryep360"/> Schoebel, in his book ''History of the Origin and Development of Indian Castes'' published in 1884, spoke of Tamil Brahmins as "Mahajanam" and regarded them, along with foreign migrants, as outside the dual left and right-hand caste divisions of Tamil Nadu.<ref name="ghuryep360" /> |

|||

=== Racial origin === |

|||

Iyer men and women are slightly different in physical makeup and complexion to the average Tamilian <ref name="madras_in_the_olden_time>{{cite book | title=Madras in the olden time| last=Wheeler| first=J. T.| authorlink= |coauthors=| year=1861| pages=22|publisher=Graves & Co.| location=Madras}}</ref><ref name="slaterp158" /> and this, along with the social practices and customs of Iyers are regarded as evidences of an "Aryan origin" for Tamil Brahmins.<ref name="aryans_brahmins_kerala">{{Cite web|url=http://www.shelterbelt.com/KJ/kharyans.html|title=The Coming of Aryans and Brahmins into Kerala|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Kerala Journal|author=Dr. Zacharias Thundy}}</ref><ref name = "ptsrinivasaiyengar_p55">[[#ptsrinivasaiyengar|P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, Pg 55]]</ref><ref name = "ptsrinivasaiyengar_p56">[[#ptsrinivasaiyengar|P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, Pg 56]]</ref> Moreover, some Iyer communities pay homage to the river Narmada instead of the South Indian river Cauvery in their rituals and revere legends proposing a northern origin for their community. Iyer marriage rites, especially, are a mixture of some customs regarded Aryan and some considered Dravidian. <ref name = "ptsrinivasaiyengar_p57">[[#ptsrinivasaiyengar|P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, Pg 57]]</ref><ref name = "ptsrinivasaiyengar_p58">[[#ptsrinivasaiyengar|P. T. Srinivasa Iyengar, Pg 58]]</ref>This issue is still being debated and researched by anthropologists, linguists and archaeologists alike. However, regardless of whether the "Aryan theory" of origin for Iyers is true or not, still it has often been a burning political issue in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. |

|||

Recent [[genetic]] studies amongst Iyers of [[Madurai]] reveal close proximity to populations from [[Eurasia]]n [[steppes]] of [[Central Asia]].<ref name="HLAAffinities">{{Cite web|url=http://www.geocities.com/tokyo/5220/brahmin_dna_study1.htm|title=HLA affinities of Iyers, a Brahmin population of Tamil Nadu, South India.|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=Wayne State University Press|year=1996|author=K. Balakrishnan, R. M. Pitchappan, K. Suzuki, U. Sankar Kumar, K. Tokunaga}}</ref> |

|||

<ref name="indian_caste_pop">{{cite journal | author=Michael Bamshad, Toomas Kivisild, W. Scott Watkins, Mary E. Dixon, Chris E. Ricker, Baskara B.Rao, J. Mastan Naidu, B. V. Ravi Prasad, P. Govinda Reddy, Arani Rasanayagam, Surinder S. Papiha, Richard Villems, Alan J. Redd, Michael F. Hammer, Son V. Nguyen, Marion L. Carroll, Mark A. Batzer, Lynn B. Jorde| title=Genetic Evidence on the Origins of Indian Caste Populations| journal=Genome Research| year=2001| volume=11| issue=6| url=http://genome.cshlp.org/cgi/content/full/11/6/994}}</ref> Other genetic researches have found close similarities between recent migrants and [[Bengali Brahmins]]. <ref name="genetic_bengalibrahmins">{{cite journal | author=S. KANTHIMATHI, M. VIJAYA, A. RAMESH| title=Genetic study of Dravidian castes of Tamil Nadu| journal=Indian Academy of Sciences Journal of Genetics| volume=87| issue=2| page=175-179|url=http://www.ias.ac.in/jgenet/Vol87No2/175.pdf}}</ref>However, the sharing of some haplotypes between the Iyers and some Southeast Asian populations suggests a migration through Southeast Asia to India.<ref name="HLAAffinities" /> When genetic analysis of South Asians was performed while discarding caste-based ramifications, it was observed that South Indians, in general had lesser genetic affinity with Central Asian people than the inhabitants of North India overall and the [[mitochondrial DNA]] ([[maternal]]) of Indian caste and [[tribal]] populations all emerged from the same source.<ref name="tribalandcaste">{{cite journal | author=T. Kivisild,1, S. Rootsi, M. Metspalu, S. Mastana, K. Kaldma, J. Parik, E. Metspalu, M. Adojaan, H.-V. Tolk, V. Stepanov, M. Go¨lge, E. Usanga, S. S. Papiha, C. Cinniog˘lu, R. King, L. Cavalli-Sforza, P. A. Underhill, and R. Villems| title=The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations| journal=American Journal of Human Genetics| year=2003| volume=72| page=313-332| url=http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/AJHG_2003_v72_p313-332.pdf}}</ref><ref name="genetics_thehindu">{{cite news | last= Ranganna| first=T.S. | title= People in north and south India belong to the same gene pool: ICHR Chairman | date=[[June 24]],[[2006]] | url=http://www.hinduonnet.com/2006/06/24/stories/2006062412870400.htm | work =The Hindu: Karnataka | accessdate = 2008-08-27}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Edgar Thurston classified Iyers as mesocephalic with an average [[cephalic index]] of 74.2<ref name="castesandtribes_lxiii">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Introduction, Pg lxiii</ref> and average nasal index of 95.1 based on the anthropological survey he had conducted in the Madras Presidency.<ref name="castesandtribes_li">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Introduction, Pg li</ref> The Kerala Iyer was found to have a cephalic index of 74.5 <ref name="castesandtribes_lxiii" />and nasal index of 92.9.<ref name="castesandtribes_li" /> |

|||

== Population and distribution == |

|||

[[Image:India Chola Nadu locator map.svg|thumb|right|200px|Though Iyers are distributed almost evenly all over the Indian state of Tamil Nadu, an extensive majority resides in the [[Chola Nadu]] region of Tamil Nadu comprising the delta of the [[Cauvery|River Cauvery]] ''(indicated by the shaded portion in the map)'' which is the traditional home of the Tamil Brahmin population]] |

|||

Today, Iyers live all over [[South India]], but an overwhelming majority of Iyers continue to thrive in [[Tamil Nadu]]. Tamil Brahmins form an estimated 3% of the state's total population and are distributed all over the state<ref name="pop" />. However, accurate statistics on the population of the Iyer community is unavailable<ref name="pop" />. |

|||

They are concentrated mainly along the [[Cauvery]] Delta [[districts]] of [[Mayiladuthurai]], [[Thanjavur District|Thanjavur]] <ref name="imperial_gazetteer_p260">{{cite book | title=The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume XVI| last=| first=| year=1908| pages=260| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=London}}</ref><ref name="imperial_gazetteer_p20">{{cite book | title=The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume XVI| last=| first=| year=1908| pages=20| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=London}}</ref> and [[Tiruchirapalli District|Tiruchirapalli]] where they form almost 10% of the total population<ref name="ghuryep393">[[#G. S. Ghurye|G. S. Ghurye]], Pg 393</ref>. In Northern Tamil Nadu they are found in the [[urban area]]s of [[Chennai]]<ref name="imperial_gazetteer_p272">{{cite book | title=The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume XVI| last=| first=| year=1908| pages=272| publisher=Clarendon Press| location=London}}</ref>, [[Kanchipuram]], [[Chengalpattu]], [[Sriperumbudur]] and [[Vellore]]. They are almost non-existent in [[rural]] parts.<ref name="madura_gazetteer">{{cite book | title=Madura District Gazetteer Vol 1| last=Francis| first=W.| date=1906| pages=84| publisher=Government of Madras| location=Madras}}</ref> |

|||

Iyers are also found in fairly appreciable number in Western and Southern districts of Tamil Nadu.<ref name="folktalesofsouthernindiap6">[[#Folk Tales of Southern India|Folk Tales of Southern India]], Pg 6</ref> Iyers of the far south are called [[Tirunelveli]] Iyers<ref name="Tirunelveli_iyers_pop">{{cite book | title=Manual of the Tinnevelly District in the Presidency of Madras| last=Stuart| first=A. J.| year=1879| pages=15|publisher=Government of Madras|id=}}</ref> and speak the Tirunelveli Brahmin dialect. The most prominent Tirunelveli Iyer was [[Subramanya Bharathi]], often regarded as the "[[national poet]] of Tamil Nadu". In [[Coimbatore]], there are a large number of Kerala Iyers from Palakkad.<ref name="colorful_festival_hindu">{{cite news | last= Prabhakaran| first=G. | title= A colourful festival from a hoary past | date=[[Nov 12]],[[2005]] | url=http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/mp/2005/11/12/stories/2005111200510400.htm | work =The Hindu Metro Plus:Coimbatore | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref> |

|||

Telugu-speaking [[Smartha]] Brahmins, especially of the [[Mulukanadu]] sect, often identify themselves as Iyers in Tamil Nadu. They are found all along coastal [[Andhra Pradesh]] and North Tamil Nadu. The fall of the [[Vijayanagar Empire]] in 1565 prompted large scale migrations from Vijayanagar as thousands of Telugu Brahmins moved southwards and settled in the districts of Tamil Nadu.<ref name="melattur_bhagavathar_mela">{{cite news | last= S. Natarajan| first=Melattur | title= Melattur, a seat of Bhagavata Mela - an overview (Part I) | date=[[March 21]],[[2004]] | url=http://www.narthaki.com/info/articles/art108.html | work =narthaki.com, Online Indian Dance Journal | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref> There were also periodic migrations from the southern districts of Andhra Pradesh during the 19th and early 20th centuries when Southern and Eastern districts of Andhra Pradesh were parts of Madras province.Savant [[Tyagaraja]], the [[Paramacharya]] of the Kanchi mutt and singer [[S.P.Balasubrahmanyam|S.P.Balasubramanyam]] are prominent Iyers of Telugu origin. |

|||

== Subsects == |

|||

Iyers have many sub-sects among them, such as [[Vadama]], Brahacharnam or [[Brahatcharanam]], [[Vadhima|Vathima]], [[Sholiyar]] or [[Sholiyar|Chozhiar]] , Ashtasahasram, Mukkani and [[Gurukkal Brahmins|Gurukkal]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p333">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], p 333</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p334">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], p 334</ref><ref name="kamat_potpourri">{{Cite web|url=http://www.kamat.com/kalranga/people/brahmins/list.htm|title=List of Brahmin communities|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Kamat's Potpourri|author=Vikas Kamat}}</ref><ref name="Leach">{{cite book | title=Aspects of caste in south India, Ceylon, and north-west Pakistan. Cambridge [Eng.]| last=Leach| first=E. R.| authorlink= |coauthors=| year=1960| pages=368|publisher=Published for the Dept. of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University Press| location=Madras}}</ref>Each sub-sect is further subdivided according to the village or region of origin. |

|||

[[Image:Brahacharnam holy man 1909.jpg|thumb|250px|left|A Tamil Smartha Brahmin holy man engaged in Siva-worship. His body is covered by coat and chains made of ''Rudraksha'' beads]] |

|||

=== Vadama === |

|||

{{See also|Vadama}} |

|||

The Vadamas regard themselves the most superior of Smartha Brahmins.<ref name="castesandtribes_p334" /><ref name="vadama_meaning_stein">{{cite book | title=Peasant State and Society in Medieval South India| last=Stein| first=Burton| year=1980| pages=210| publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> The word "Vadama" is derived from the Tamil word ''Vadakku'' meaning North.<ref name="vadama_meaning">{{cite book | title=Early South Indian Paleography| last=Mahalingam| first=T. V. | year=1967| pages=296| publisher=University of Madras}}</ref> Due to this reason, it is widely speculated that the Vadamas could have been the latest of the Brahmin settlers of the Tamil country.<ref name="vadama_meaning_stein" /> At the same time, however, the honorific title ''Vadama'' could also be used simply to denote the level of Sanskritization and cultural affiliation and not as evidence for a migration at all.<ref name="madras_bulletin">{{cite book | title=Bulletin of the Institute of Traditional Cultures| year=1957| pages=141| publisher=Institute of Traditional Cultures}}</ref> |

|||

Many Vadamas follow a number of Vaishnavite religious beliefs and practices.<ref name="castesandtribes_p334" /> They sport the ''urdhvapundram'' mark on their forehead unlike other sects of Iyers. <ref name="castesandtribes_p334" /> A large section of the Iyengar community is believed to be made of converted Vadamas. There are also vadamas who were involved in the revival of saivism and shaktism in Tamil Nadu. <ref>http://chennaionline.com/hotelsandtours/Placesofworship/2005/07temple51.asp</ref><ref>http://www.dlshq.org/saints/appayya.htm</ref>.<ref>http://www.geocities.com/vienna/strasse/5926/shyamabio.htm,</ref> One such saint Appayya Dikshitar set about to prove that Ramayana and Mahabharata were written in order to bring glory to Lord Shiva.<ref>http://www.shaivam.org/adappayya_works.htm</ref> |

|||

The Vadamas are classified into Vadadesa Vadama, Choladesa Vadama, Sabhaiyar, Inji and Thummagunta Dravida.<ref name="castesandtribes_p334" /> |

|||

=== Vathima === |

|||

{{See also|Vathima}} |

|||

The Vathimas are few in number and are confined mostly to eighteen villages in [[Thanjavur district]]. They are sub-divided into Pathinettu Gramathu Vathima or Vathima of the eighteen villages, Udayalur, Nannilam and Rathamangalam.<ref name="castesandtribes_p337">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 337</ref> |

|||

=== Brahacharnam === |

|||

{{See Also|Brahatcharanam}} |

|||

Brahacharnam is a corruption of the Sanskrit word ''Brahatcharnam'' means "the great sect".<ref name="castesandtribes_p335">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 335</ref> Brahacharnams are more Saivite than Vadamas and are sub-divided into Kandramaicka, Milanganur, Mangudi, [[Palamaneri Iyers|Pazhamaneri]], Musanadu, Kolathur, Marudancheri,Sathyamangalam and Puthur Dravida.<ref name="castesandtribes_p335" /> |

|||

=== Ashtasahasram === |

|||

The Ashtasahasrams are, like the Brahacharnams, more Saivite than the Vadamas.<ref name="castesandtribes_p338">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 338</ref> They are further sub-divided into Aththiyur, Arivarpade, Nandivadi and Shatkulam.<ref name="castesandtribes_p338" />. |

|||

=== Dikshitar === |

|||

[[Image:Dikshitar.JPG|thumb|right|A ''Dikshitar'' from Chidambaram]] |

|||

The Dikshitars are based mainly in the town of [[Chidambaram]] and according to legend, have descended from three thousands individuals who migrated from [[Varanasi]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p338" /> They wear their [[kudumi]] in front of their head like the [[Nairs]] and [[Nambudiris]] of [[Kerala]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p338" /> |

|||

=== Chozhiar or Sholiyar === |

|||

The Sholiyars serve as priests, cooks or decorate idols in Hindu temples.<ref name="castesandtribes_p341">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 341</ref> According to legend, they are believed to have descended from [[Chanakya]], the minister of [[Chandragupta Maurya]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p342">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 342</ref> They are divided into Tirukattiur, Madalur, Visalur, Puthalur, Senganur, Avadiyar Koil.<ref name="castesandtribes_p340">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 340</ref> |

|||

=== Gurukkal === |

|||

{{See also|Gurukkal Brahmins}} |

|||

The sect of Sivacharya or Gurukkal form the hereditary priesthood or in the Siva and Sakthi temples in Tamil Nadu<ref name="castesandtribes_p347">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 347</ref><ref name="Gurukkal" />. They are Saivites and adhere to the philosophy of [[Shaiva Siddhanta]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p347" /> They are well versed in Agama Sasthras and follow the Agamic rituals of these temples.<ref name="castesandtribes_p347" /> |

|||

Gurukkals are sub-divided into Tiruvalangad, Conjeevaram and Thirukkazhukunram.<ref name="castesandtribes_p347" /> |

|||

=== Mukkani === |

|||

The Mukkani sub-sect of Iyers are traditionally helpers to the priests in the temples of [[Thiruchendur]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p342">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 342</ref> Legend has it that the Mukkanis were the '''bhoothaganas''', the demon bodyguards of [[Lord Siva]] and that they were given the responsibility for guarding Subrahmanya's shrines by Siva.<ref name="Mukkanis">{{Cite web|url=http://www.keralaiyers.com/subsects|title=Subsects|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=keralaiyers.com|author=}} |

|||

</ref>. The Mukkanis predominantly subscribe to the [[Rig Veda]]. |

|||

=== Kaniyalar === |

|||

The Kaniyalar are a little known sub-sect of Iyers. A large number of Kaniyalars serve as cooks and menial servants in Vaishnavite temples.<ref name="castesandtribes_p342" /> Hence, they sport the ''namam'' like Vaishnavite [[Iyengars]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p342" /> |

|||

=== Prathamasaki === |

|||

The Prathamasakis form another little-known sub-sect of Iyers. They follow the White Yajur Veda.<ref name="castesandtribes_p344">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 344</ref> According to Hindu legend, in remote antiquity, the Prathamasakis were cursed by God to spend one hour every day as [[Paraiyar|Parayars]]<ref name="castesandtribes_p345">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 345</ref> and hence they are known as "Madhyana Paraiyans" in [[Thanjavur district|Tanjore district]]<ref name="castesandtribes_p344" /> and are regarded inferior by other sects of Brahmins.<ref name="castesandtribes_p344" /> |

|||

Edgar Thurston also mentions another sect of Iyers called ''Kesigal'' or ''Hiranyakesigal''.<ref name="castesandtribes_p335">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 335</ref> However, this sub-sect appears to have disappeared or merged into the larger Vadama community with the passage of time. |

|||

Iyers are also divided into different sects based on the [[Vedas|Veda]] they follow.<ref name="castesandtribes_p267">[[#Castes and Tribes of South India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 267</ref> Iyers belonging to the [[Yajur Veda]] sect usually follow the teachings of the Krishna Yajur Veda.<ref name="castesandtribes_p268" /><ref name="subsects_keralaiyers">{{Cite web|url=http://www.keralaiyers.com/subsects|title=Subsects|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=keralaiyers.com}}</ref> |

|||

== Gotra or Lineage == |

|||

{{See Also|Brahmin gotra system}} |

|||

Iyers, like all other Brahmins, trace their paternal ancestors to one of the eight ''[[rishi]]s'' or sages.<ref name="gotra_def">{{Cite web|url=http://vedabase.net/g/gotra|title=Definition of the word ''gotra''|accessdate=2008-08-19}}</ref><ref name="gotra_description">{{Cite web|url=http://www.gurjari.net/ico/Mystica/html/gotra.htm|title=Gotra|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=gurjari.net}}</ref> Accordingly they are classified into eight ''[[gotra]]s'' based on the ''rishi'' they have descended from. A maiden in the family belongs to gotra of her father, but upon marriage takes the ''gotra'' of her husband. |

|||

== Migrations == |

|||

=== Migration to Karnataka === |

|||

Over the last few centuries, a large number of Iyers have also migrated and settled in parts of [[Karnataka]]. The erstwhile [[Mysore state]] had been home to a significantly large Mulukanadu community. During the rule of the Mysore Maharajahs, a large number of Iyers from the then [[Madras Presidency|Madras province]] migrated to Mysore. The [[Ashtagrama Iyer]]s are also a prominent group of Iyers in Karnataka<ref name="ashtagramaiyer_history">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ashtagrama.com/wst_page2.html|title=Brief history of ''Ashtagrama''|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Ashtagrama Iyer community website|author=}}</ref>. |

|||

=== Migrations to Kerala === |

|||

A series of large-scale migrations of Iyers from the Tamil country into Kerala over the past few centuries has created a 'Kerala Iyer' community<ref name="Kerala" /><ref name="keralaiyers_migrationtheories">{{Cite web|url=http://www.keralaiyers.com/migrationtheories|title=Migration Theories|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=keralaiyers.com}}</ref>. According to [[anthropologists]], two streams of migration actually took place: |

|||

* A wave of migrations from [[Tirunelveli]] and [[Ramnad]] [[districts]] of Tamil Nadu first to the erstwhile [[princely states]] of [[Travancore]] and [[Cochin]] and later to [[Palakkad]] and [[Kozhikode]] districts have resulted in the origin of an Iyer community in the Travancore and Cochin regions. |

|||

* There were also migrations rom [[Tanjore]] district of Tamil Nadu to Palakkad. Their descendants are known today as [[Palakkad Iyers]].<ref name="permaul_p300" /><ref name="permaul_p308">[[#Cochin, Its past and present|Cochin, Its past and present]], Pg 308</ref> |

|||

==== Iyers in Travancore and Cochin regions ==== |

|||

A majority of the Iyers living in the historic [[Travancore]] and [[Cochin]] regions of Kerala are the descendents of 18th century migrants from the former [[Pandya]] kingdom and the Madras Presidency<ref name="Kerala">{{Cite web|url=http://www.kuzhalmannamagraharam.info/articles/kerala-iyer-history.html|title=History of Kerala iyers and Agraharams|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Kuzhalmanna Agraharam website|author=}}</ref><ref name="keralaiyers_migration">{{Cite web|url=http://www.keralaiyers.com/migration|title=Migration Theories|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=keralaiyers.com}}</ref>. However, Iyers were neither considered eligible nor allowed to officiate as priests in the temples of [[Kerala]] as the priests in these parts practised 'Tantra Vidhi'- a very complex system of [[Tantric]] rites monopolized by the [[Nambudiri|Namboothris]]<ref name="Kerala Iyers" />. The only exception is the district of [[Kanyakumari district|Kanyakumari]] in Tamil Nadu which was formerly a part of [[Travancore|Travancore state]]. .{{Facts|date=June 2008}} |

|||

Due to their skill in [[culinary]] art, Iyers were initially employed mostly as cooks. They are generally credited with having introduced Tamil delicacies as ''[[idli]]'', ''[[sambhar]]'', ''[[dosa]]'' and ''[[vadai]]'' in Kerala. However, with the passage of time, Iyers entered administrative and commercial professions as well. |

|||

The first prominent member of the Iyer community in Kerala was [[Ramayyan Dalawa]], who was the Prime Minister (''Dewan'' or ''Dalawa'') of Travancore State during the reign of Raja [[Marthanda Varma]]. Other prominent Iyers from Kerala include [[Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer]], [[Malayattoor Ramakrishnan]], [[V. R. Krishna Iyer]] and [[T. N. Seshan]]. |

|||

Tamil Brahmins have fully [[racial integration|integrated]] into Kerala society even while retaining their ancestral traditions. Their mother tongue is a dialect of [[Brahmin Tamil|Tamil]] heavily influenced by [[Malayalam]] vocabulary. During the 19th century, Iyers, like Malayali Nambudhiris, even adopted the Malayali practice of ''[[sambandham]]'' though the numbers contacting such alliances were very low <ref name="castesandtribes_p355">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 355</ref> |

|||

==== Palakkad Iyers ==== |

|||

Iyers who migrated to the [[Palakkad district]] from the [[Chola]] kingdom to serve in the temples of Kerala are known as [[Palakkad Iyers]]. From the very beginning, the Palakkad Iyers were endowed with grants of land and were pretty well-off compared to the Travancore and Cochin Iyers. They also officiated in [[temples]] as priests. The Palakkad Iyers resided in [[agraharams]]<ref name="colorful_festival_hindu" /><ref name="agraharams">{{Cite web|url=http://kbspalakkad.org/palakkad/palakkad.htm|title=Palakkad District|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Kerala Brahmana Sabha|author=}}</ref> . Those who established themselves in the interior parts of Kerala lived in houses known as 'Madom'<ref name="agraharams" /><ref name="madhom">{{Cite web|url=http://www.samooham.com/|title=Ernakulam Gramajana Samooham Home Page|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Ernakulam Gramajana Samooham|author=}}</ref>. |

|||

The Palakkad Iyers were greatly affected by the Kerala Agrarian Relations Bill, 1957 (repealed in 1961 and substituted by The Kerala Land Reforms Act, 1963) which abolished the [[tenancy]] system.<ref name="keralagovt_legislations">{{Cite web|url=http://niyamasabha.org/codes/bus_1_1.htm|title=Landmark Legislations - Land Reforms|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Kerala Legislative Assembly|author=}}</ref> |

|||

=== Migrations to Sri Lanka === |

|||

According to a [[primary source]] called [[Mahavamsa]], Brahmins in general are known in written [[Sri Lanka]]n history from the beginnings of Indic migrations to the island from about 500 BCE. Currently Tamil Brahmins are an important part of the [[Sri Lankan Tamil]] ethnic group in Sri Lanka.<ref name="civattampip3">{{cite book | title=Sri Lankan Tamil society and politics| last=Civattampi| first=K.| year=1995| pages=3| publisher=New Century Book House| location=Madras| id=ISBN 812340395X }}</ref><ref name="ritualizingontheboundariesp3">[[#Ritualizing on the Boundaries|Ritualizing on the Boundaries]], Pg 3</ref> Tamil Brahmins played an important historic role in the formation of the [[Jaffna Kingdom]] circa thirteenth century.<ref name="ritualizingontheboundariesp3" /><ref name="criticalhistoryofjaffna">{{cite book | title=A critical history of Jaffna| last=Gnanaprakasar| first=S.|year=1928|pages=96| publisher=Gnanaprakasa Yantra Salai|id=ISBN 8120616863, ISBN 9788120616868}}</ref> (See [[Aryacakravarti dynasty]])<ref name="pathmanathan">[[#Pathmanathan|Pathmanathan]], Pg 1-13</ref> |

|||

=== Recent migrations === |

|||

Apart from [[South India]], Iyers have also migrated to and settled in places in [[North India]]. There are significantly large Iyer communities in [[Mumbai]]<ref name="ritualizingontheboundariesp86">[[#Ritualizing on the Boundaries|Ritualizing on the Boundaries]], Pg 86</ref><ref name="ritualizingontheboundariesp12">[[#Ritualizing on the Boundaries|Ritualizing on the Boundaries]], Pg 12</ref>, [[Kolkata]], [[Orissa]] and [[Delhi]]. These migrations, which commenced during the British rule, were often undertaken in search of better prospects and contributed to the prosperity of the community<ref name="Tambram" />. |

|||

In recent times Iyers have also migrated in large numbers to the [[United Kingdom]], [[Europe]] and the [[USA]]<ref name="ritualizingontheboundariesp12" /> in search of better fortune. They are one of the fastest growing Asian communities in the US. |

|||

== Religious practices, ceremonies and festivals == |

|||

=== Rituals === |

|||

Iyer rituals comprise rites as described in [[Hindu scripture]]s such as [[Apastamba|Apastamba Sutra]] attributed to [[Apastamba]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p268">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 268</ref> The most important rites are the shodasa samskaras or the 16 essential [[Saṃskāra]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p270">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 270</ref> Although many rites and rituals that were practiced in ancient times are no longer followed, some traditions are continued to this day<ref name="16Samskaras">{{Cite web|date=[[August 8]],[[2003]]|url=http://www.commsp.ee.ic.ac.uk/~pancham/Articles/The%20Sixteen%20Samskaras.pdf|title=The Sixteen Samskaras Part-I|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=|author=}}.</ref><ref name="samskaras_names">{{Cite web|url=http://www.kamakoti.org/hindudharma/part16/chap8.htm|title=Names of Samskaras|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=kamakoti.org|author=}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Brahmins ablution.gif|thumb|250px|Iyers from [[South India]] performing the Sandhya Vandhanam, 1913]] |

|||

Iyers are initiated into rituals at the time of birth. In ancient times, rituals used to be performed when the baby was being separated from mother's umbilical cord. This ceremony is known as '''Jatakarma'''<ref name="jatakarma1">{{Cite web|url=http://www.subhakariam.com/samskara/jatakarma.htm|title=Jatha karma|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=|author=Rajagopala Ghanapatigal}}</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p272">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 272</ref>. However, this practice is no longer observed. At birth, a [[horoscope]] is made for the child based on the position of the stars. The child is then given a ritual name with a grand Hindu ritual<ref name="castesandtribes_p272" /><ref name="Ayush Homam">{{cite news | last= Austin| first=Lisette | title= Welcoming baby; Birth rituals provide children with a sense of community, culture | date=[[May 21]],[[2005]] | url=http://www.parentmap.com/content/view/498/276/ | work =Parentmap | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref>. On the child's birthday (especially the first one) a Hindu ritual is performed to ensure longevity. This ritual is known as [[homas| Ayushya Homam]]. This ceremony is held on the child's birthday reckoned as per the Tamil calendar based on the position of the [[nakshatra]]s or stars and not the [[Gregorian calendar]]<ref name="Ayush Homam" />. The child's first birthday is the most important and is the time when the baby is formally initiated by piercing the ears of the boy or girl. From that day onwards a girl is expected to wear earrings. |

|||

A second initiation (for the male child in particular) follows when the child crosses the age of seven.<ref name="universalhistory_1781_107">[[#universalhistory_1781|An Universal History]], Pg 107</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p273">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 273</ref> This is the [[Upanayana]] ceremony during which a [[Brahmin|Brahmana]] is said to be reborn.<ref name="castesandtribes_p273" /><ref name="castesandtribes_p277">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 277</ref> A three-piece cotton thread is installed around the [[torso]] of the child encompassing the whole length of his body from the left [[shoulder]] to the right [[hip]].<ref name="universalhistory_1781_107" /><ref name="castesandtribes_p274">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 274</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p277" /><ref name="castesandtribes_p278">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 278</ref> The Upanayana ceremony of initiation is solely performed for the members of the [[dvija]] [[castes]], generally when the individual is between 7 and 16 years of age.<ref name="upanayanam">{{Cite web|url=http://www.gurjari.net/ico/Mystica/html/upanayanam.htm|title=Upanayanam|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=gurjari.net|author=}}</ref><ref name="iyer_ritesandrituals">{{Cite web|url=http://www.boloji.com/hinduism/047.htm|title=Customs and Classes of Hinduism|date=[[March 2]], [[2003]]|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=Boloji Media Inc.|author=Neria Harish Hebbar}}</ref> In ancient times, the Upanayana was often considered as the ritual which marked the commencement of a boy's education<ref name="castesandtribes_p276">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 276</ref>, which in those days, comprised mostly of the study of the Vedas. However, with the Brahmins taking to other [[vocations]] than [[priesthood]], this initiation has become more of a symbolic ritual these days.The [[neophyte]] was expected to perform the [[Sandhya Vandana]]m ritual<ref name="castesandtribes_p313">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 313</ref><ref>[http://rds.yahoo.com/_ylt=A0geu6yffRFHMHAA5ihXNyoA;_ylu=X3oDMTExbTV0dDR1BHNlYwNzcgRwb3MDMQRjb2xvA2FjMgR2dGlkAwRsA1dTMQ--/SIG=12i54k7sd/EXP=1192415007/**http%3a//www.tiehh.ttu.edu/gopal/2005%2520Upakarma%2520vidhi.pdf A Description of the Sandhya Vandanam]</ref> and utter a prescribed set of prayers, three times a day: dawn, mid-day, and dusk. The most sacred and prominent of the prescribed set of prayers is the [[Gayatri Mantra]],<ref name="castesandtribes_p312">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 312</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p313" /><ref>[http://www.gayathrimanthra.com/contents/gayathri/gayathrimanthram.html The Meaning of the Gayatri Manthra and its Description]</ref> which is as sacred to the Hindus as the [[Kalima]] to the [[Muslims]] and [[Ahuna Vairya|Ahunwar]] to the [[Zoroastrians]].<ref name="castesandtribes_p313" /> Once a year (usually in the month of August or September) Iyers change their sacred thread. This ritual is exclusive to South Indian Brahmimns and the day is commemorated as 'Avani Avittam'. |

|||

Other important ceremonies for Iyers include the rites for the deceased. <ref name="castesandtribes_p299">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 299</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p300">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 300</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p301">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 301</ref>All Iyers are cremated according to [[Historical Vedic religion|Vedic]] rites, usually within a day of the individual's death<ref name="castesandtribes_p298">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 298</ref><ref name="deathrites_majorreligions">{{Cite web|url=http://www.beliefnet.com/story/78/story_7894_2.html|title=Transition Rituals|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=Beliefnet Inc.|author=}}</ref>. The death rites include a 13-day ceremony, and regular ''[[Tarpanam]]''<ref name="Tharpanam">{{Cite web|url=http://www.vadhyar.com/Tarpanam.php|title=Tharpanam|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=vadhyar.com|author=}}</ref>(performed every month thereafter, on [[Amavasya]] day, or New Moon Day), for the ancestors.<ref name="castesandtribes_p298" /><ref name="castesandtribes_p303">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 303</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p304">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 304</ref>There is also a yearly ''[[Shraadh|shraarddha]]'', that must be performed.<ref name="castesandtribes_p304" /><ref name="castesandtribes_p305">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 305</ref> These rituals are expected to be performed only by male descendants of the deceased. Married men who perform this ritual must be accompanied by their wives. The women are symbolically important in the ritual to give a "consent" to all the proceedings in it<ref name="journey_of_a_lifebody>{{Cite web|url=http://www.hindugateway.com/library/rituals/|title=The Journey of a Lifebody|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Hindu Gateway|author=David M. Knipe}}</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p298" />. |

|||

=== Festivals === |

|||

{{See Also|Hindu festivals}} |

|||

Iyers celebrate almost all Hindu festivals like [[Deepavali]], [[Navratri]], [[Pongal]], [[Vinayaka Chaturthi]], [[Janmaashtami|Janmāshtami]], [[Tamil New Year]], [[Sivarathri]] and Karthika Deepam. |

|||

However, the most important festival which is exclusive to Brahmins of South India is the Avani Avittam festival.<ref name="Avani_Avittam">{{Cite web|url=http://www.panchangam.com/avani.htm|title=Avani Avittam|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=K.G.Corporate Consultants|author=}}</ref> |

|||

=== Weddings === |

|||

{{See Also|Hindu weddings}} |

|||

A typical Iyer wedding consists of ''Sumangali Prārthanai'' (Hindu prayers for prosperous married life) , ''Nāndi'' (homage to ancestors), ''Nischayadhārtham'' (Engagement)<ref name="castesandtribes_p278" /> and ''Mangalyadharanam'' (tying the knot).<ref name="castesandtribes_p285">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 285</ref> This is a highly ritualistic affair. The main ritualistic events of an Iyer marriage include ''Vratam'' (fasting), ''Kasi Yatra'' (pilgrimage to Kasi), ''Oonjal'' (Swing), ''Kanyadanam'' (placing the bride in the groom's care), ''Mangalyadharanam'', ''Pānigrahanam'' <ref name="castesandtribes_p286">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 286</ref>and ''Saptapathi'' (or ''seven steps'' - the final and most important stage wherein the bride takes seven steps supported by the groom's palms thereby finalizing their union).<ref name="castesandtribes_p286" /> This is usually followed by ''Nalangu'', which is a casual and informal event.<ref name="Iyer_marriage"> {{Cite web|url=http://www.sawnet.org/weddings/tamil_vedic.html|title=A South Indian Wedding – The Rituals and the Rationale|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Sawnet|author=Padma Vaidyanath}}</ref><ref name="castesandtribes_p290">[[#Castes and Tribes of Southern India|Castes and Tribes of Southern India]], Pg 290</ref> |

|||

== Lifestyle and culture == |

|||

{{See Also|Culture of Tamil Nadu}} |

|||

=== Traditional Iyer ethics === |

|||

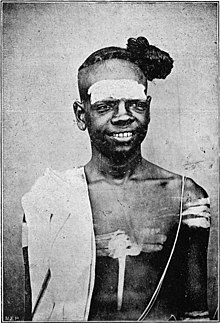

[[Image:Mvsivan.jpg|thumb|left|A traditional-looking Iyer -- M.V.Sivan, a prominent vocalist from the 19th century]] |

|||

Iyers are generally orthodox Hindus who adhere steadfastly to their customs and traditions. However, of recent, they have started leaving their traditional priestly duties for more secular vocations, causing contemporary Iyers to be more flexible than their parents and grandparents. They followed the [[Manusmriti]] (Hindu Code of Laws or The Institutes of Manu) and the Grihya Sutras of [[Apastamba]] and [[Baudhayana]]. The society is patriarchal but not feudal.<ref name="apastamba_sutra">{{cite book | title=Yajur-Veda: Apastamba-Grhya-Sutra| last=Pandey| first=U. C. | date=1971}}</ref><!--removing possible copyvio image[[Image:Paramacharya.jpg|thumb|left|Shankaracharya of Kanchi, Jagadguru Chandrasekharendra Saraswati, also known as "Paramacharya"]] . --> |

|||

Iyers observed many rules in the past when they used to live and marry only within their community; many continue to adhere to their roots. Their dietary habits can be considered to be strict, consuming only vegetarian food which excludes fish and fowl, eggs and egg products. Some abjure onion and garlic on the grounds that they activate certain base senses. Milk and milk products, preferably from the cow, were approved.<ref name="universalhistory_1781_104">[[#universalhistory_1781|An Universal History]], Pg 104</ref> They were mandated to avoid the consumption of intoxicants, including alcohol and tobacco<ref name="Manusmriti" /><ref name="universalhistory_1781_104" />. |

|||

[[Image:Iyer.jpg|thumb|right|An Iyer man dressed in traditional clothes for a Hindu ritual]] |

|||

Iyers follow elaborate purification rituals, both of self and the house. The women of the household cook food only after a bath, while the males perform religious rites after a purificatory bath. An Iyer does not visit a temple without taking bath. Food is partaken of only after it is offered to the deity/deities in a prescribed manner. Like any other Brahmin community, bathing everyday is mandatory, and is, strictly speaking, the first thing to be carried out, before beginning any work of the day or before the start of any ritual or prayer. So much importance was given to this, that it was not unusual to see Iyers bathe many times during the day (before performing any important ritual).<ref name="Madi">{{Cite web|url=http://www.icsi.berkeley.edu/~snarayan/anthro-pap/subsection3_4_1.html|title=The Practice of ''madi''|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=ICSI Berkeley|author=}}</ref> |

|||

The bathing was considered sufficiently purifying only if it confirmed to the rules of ''madi''<ref name="Madi" />. The word ''[[madi]]'' is used by Tamil Brahmins to indicate that a person is bodily pure. |

|||

In order to practice madi, the brahmin had to wear only clothes which had been recently washed and dried, and the clothes should remain untouched by any person who was not ''madi''. Only after taking bath in cold water, and after wearing such clothes, would the person be in a state of ''madi''. |

|||

This practice of ''madi'' is followed by Iyers even in modern times, before participating in any kind of religious ceremony<ref name="Madi" />. |

|||

[[Image:Madras Kappi.jpg|thumb|left|As alcoholic beverages are prohibited according to the ''Manusmriti'', Iyers have taken a special liking for coffee <ref name="oasis_vegetarian">{{cite news | last= Lakshmi| first=S. | title= An oasis of vegetarian calm | date=[[February 23]],[[2008]] | url=http://www.business-standard.com/common/news_article.php?leftnm=way&autono=314701 | work =Business Standard | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref><ref name="art_of_slurping">{{cite news | last= | first= | title= The Art of Slurping | date=[[December 23]],[[2001]] | url=http://www.hinduonnet.com/mag/2001/12/23/stories/2001122300030400.htm | work =The Hindu | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref>]]. |

|||

Until the turn of the last century, an Iyer widow (but not a widower) was never allowed to remarry. Divorces were considered a "great evil". Once a widow, an Iyer woman had to shave her head and lead the life of [[Sanyasin]]. She had to stop wearing the kumkum/bindi on her forehead, and was recommended to smear her forehead with [[sacred ashes]]. All of these practices have diminished over the last few decades, and modern Iyer widows lead less orthodox lives<ref name="brahminwomenp171">[[#Brahmin Women|Brahmin Women]], Pg 171</ref>. |

|||

=== Traditional attire === |

|||

[[Image:MylaiTamizhSangam.jpg|thumb|right|Tamil Brahmins (Iyers and Iyengars) in traditional ''veshti'' and ''angavastram'' at a convention of the Mylai Tamil Sangam, circa early 1900s]] |

|||

Iyer men traditionally wear ''[[veshti]]s'', which cover them from waist to foot. These are made of [[cotton]] and sometimes [[silk]]. ''Veshtis'' are worn in different styles. They are worn in typical brahminical style during religious ceremonies. This style is popularly known as '''panchakacham'''(from the [[sanskrit]] terms ''pancha'' and ''gajam'' meaning "five yards" as the length of the ''panchakacham'' is five yards in contrast to the ''veshtis'' used in non-ceremonial daily life is, by contrast, four or eight cubits long). They sometimes wrap their shoulders with a single piece of cloth known as ''angavastram'' (body-garment). In earlier times, Iyer men who performed austerities also draped their waist or chests with deer skin or grass. |

|||

The traditional Iyer woman is draped in a nine yard saree, also known as [[madisar]] in Tamil.<ref name='madisar">{{cite news | last= | first= | title= A saree caught in a time wrap | date=[[January 23]], [[2005]] | url =http://www.tribuneindia.com/2005/20050123/society.htm#2 | work =The Tribune | accessdate = 2008-09-03}}</ref> Though such dress is worn regularly only by the older women these days, on festivals and other religious occasions younger women wear it as well. |

|||

=== Iyers and art === |

|||

[[Image:DKPattammal-DKJayaraman-young.jpg|thumb|left|DK Pattammal (right) ,Classical Music Singer, in concert with her brother, DK Jayaraman; ''circa'' early 1940s.]] |

|||

For centuries, Iyers have taken a keen interest in preserving the arts and sciences. They undertook the responsibility of preserving the [[Natya Shastra of Bharata|Bharata Natya Shastra]], a monumental work on [[Bharatanatyam]], the classical dance form of Tamil Nadu. During the early 20th century, dance was usually regarded as a degenerate art associated with [[devadasi]]s. However, it was an Iyer woman, [[Rukmini Devi Arundale]], who revived the dying art form thereby breaking social and caste taboos about Brahmins taking part in the study and practice of the traditional dance form of Bharatanatyam, an art then considered degenerate<ref>''Roles and Rituals for Hindu Women'' By Julia Leslie, Pg. 154</ref><ref name="natyam_academy">{{cite news | last=Vishwanathan | first= Lakshmi | title= How Natyam danced its way into the Academy | date=[[December 1]],[[2006]] | |

|||

url=http://www.hindu.com/ms/2006/12/01/stories/2006120100180600.htm | work =The Hindu | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref>. |

|||

However, compared to dance, the contribution of Iyers in field of music has been considerably noteworthy<ref>''From the Tanjore Court to the Madras Music Academy: A Social History of Music in South India'' by Lakshmi Subramanian ISBN-10: 0195678354</ref><ref name="carnaticmusic_popularity">{{Cite web|url=http://www.karnatik.com/article001.shtml|title=Popularity of Carnatic music|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=karnatik.com|author=Raghavan Jayakumar}}</ref>. The Trinity of Carnatic Music were responsible for making some excellent compositions towards the end of the 18th century. In more recent times, [[Chembai|Chembai Vaidyanatha Iyer]] and [[D. K. Pattammal]] have enthralled audiences with some soul-stirring renderings. Today, there are Iyers who give traditional renderings as well as playback singers in Indian films like [[S P Balasubrahmanyam]], [[Hariharan]], [[Kavita Krishnamurthy]], [[Nithyashree Mahadevan]], [[Usha Uthup]], [[Shankar Mahadevan]], [[Mahalaxmi Iyer]], [[Hamsika Iyer]] and [[Naresh Iyer]] . Iyers have also contributed considerably to [[drama]], short story and temple architecture. |

|||

In the field of literature and journalism, the Iyer community has produced stalwarts like [[R. K. Narayan]], [[R. K. Laxman]], [[Subramanya Bharathi]], [[Kalki Krishnamurthy]], [[Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer|Ulloor Parameswara Iyer]], and [[Cho Ramaswamy]] to name a few. The adoption of Western education at every stage has ensued their proficiency in the English language<ref name="Non-Brahmin Movement" /><ref>''Caste in Indian Politics'' by Rajni Kothari,Pg 254</ref>. They have also contributed in an equal amount to Tamil language and literature<ref name="Hart" /><ref>In [http://www.tamilnation.org/books/History/nambi.htm ''Tamil Renaissance and Dravidian Nationalism''] Nambi Arooran states: "However the Tamil Renaissance cannot be considered as solely the work of non-Brahmin scholars. Brahmins also played all equally important role and the contribution of U. V. Swaminatha Aiyar and C. Subramania Bharati cannot be underestimated. Similarly in the reconstruction of the Tamil past Brahmin historians such as S. Krishnaswami Aiyangar, K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar, P. T. Srinvasa Ayyangar and C. S. Srinivasachari brought out authoritative works on the ancient and medieval periods of South Indian history, on the basis of which non-Brahmins were able to look back with pride upon the excellence of Tamil culture. But some of the non-Brahmins looked at the contribution of Brahmin scholars with suspicion because of the pro-Aryan and pro-Sanskrit views expressed sometimes in their writings."</ref>.There are innumerable hymns composed on different deities worshipped in the [[South India|South]] such as [[Meenakshi]], [[Amman]], Shiva, Murugan, Vishnu, etc. The style of these poems are indeed unique and beautiful. Besides Tamil, they have also written a number of works in Sanskrit which is the language used in rituals. |

|||

The Iyer community has also produced a number of film stars and cine artistes. Two of [[Kollywood]]'s greatest directors, [[K. Balachander]] and [[Mani Ratnam]] hail from the Iyer community. [[Gemini Ganesan]] was one of the greatest Tamil film actors of the black-and-white era along with [[Sivaji Ganesan]] and [[M. G. Ramachandran]]. At present, [[Ajith Kumar|Ajith]] and [[Trisha Krishnan|Trisha]] are amongst the top five stars in Tamil cinema. |

|||

=== Food === |

|||

{{See Also|Tamil cuisine}} |

|||

[[Image:Tamil Sappadu.jpg|thumb|left|The diet of Iyers comprise mainly of Tamil vegetarian cuisine, comprising rice]] |

|||

The main diet of Iyers is composed of vegetarian food<ref name="castesandtribes_p268" /><ref name="hindu_attitude_vegetarianism">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ivu.org/congress/wvc57/souvenir/raghunathan.html|title=The Hindu Attitude Towards Vegetarianism|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=International Vegetarian Union|author=N. Raghunathan}}</ref>, mostly rice which is the staple diet for millions of South Indians.Vegetarian side dishes are frequently made in Iyer households apart from compulsory additions as rasam,sambar,etc. Home-made [[ghee]] is a staple addition to the diet, and traditional meals do not begin until ghee is poured over a heap of rice and lentils. While tasting delicious, the cuisine eschews the extent of spices and heat traditionally found in south Indian cuisine. Iyers are mostly known for their love for curd. Other South Indian delicacies such as dosas, idli, etc. are also relished by Iyers. Coffee amongst beverages and curd amongst food items form an indispensable part of the Iyer food menu. Liquor is traditionally forbidden, as per the Manusmrithi<ref name="Manusmriti">{{cite book | title=The Laws of Manu| last=Doniger| first=Wendy| coauthors=Brian K. Smith| date=1991| publisher=Penguin Books}}</ref><ref name="universalhistory_1781_104" />, and is accordingly eschewed by the Iyers. |

|||

Consumption of food is also accompanied by a ritual called ''annasuddhi'', literally meaning 'purification of rice'. Involving a few invocations and sprinkling of water, the ritual is considered essential before partaking of food, in traditional Iyer households. |

|||

== ''Agraharam'' == |

|||

[[Image:Agraharam.jpg|thumb|350px|right|Agraharam]] |

|||

In ancient times, Iyers, along with [[Iyengars]] and other [[Tamil Brahmins]], lived in exclusive Brahmin [[Quarter (country subdivision)|quarters]] of their village or town known as an '[[agraharam]]'(in Sanskrit ''Agram'' means ''tip'' or ''end'' and ''Haram'' means ''Shiva''). [[Shiva]] and [[Vishnu]] [[temples]] were usually situated at the ends of an agraharam. In most cases, there would also be a fast-flowing stream or river nearby.<ref name="quaint_charm">{{cite news | last=Sashibhushan | first= M. G. | title= Quaint charm | date=[[February 23]],[[2004]] | url=http://www.hindu.com/mp/2004/02/23/stories/2004022301910300.htm| work =Business Line | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref> |

|||

A typical agraharam consisted of a temple and a street adjacent to it. The houses on either side of the street were exclusively peopled by Brahmins who followed a joint family system. All the houses were identical in design and architecture though not in size. |

|||

With the arrival of the British and commencement of the Industrial Revolution, Iyers started moving to cities for their sustenance. Starting from the late 1800s, the agraharams were gradually discarded as more and more Iyers moved to towns and cities to take up lucrative jobs in the provincial and judicial administration. |

|||

However, there are still some agraharams left where traditional Iyers continue to reside. In an Iyer residence, people wash their feet first with water on entering the house. This is not possible in flats in cities due to the layout of the same. But in houses in villages, the layout permits this and is still practiced.<ref name="life_in_an_agrharam">{{Cite web|url=http://www.saibaba.ws/teachings/goalguide/goalguide03.htm|title=The Goal and the Guide, Petal 3:Fire Walking|accessdate=2008-08-27|publisher=Sri Satya Sai Baba Website|author=Bombai Srinivasan}}</ref><ref name="agraharam_description">{{cite news | last=Sridhar | first= Lalitha | title= Simply South | date=[[August 6]],[[2001]] | url=http://www.blonnet.com/2001/08/06/stories/100672a4.htm | work =Business Line | accessdate = 2008-08-27}}</ref> |

|||

==Language of Iyers== |

|||

{{See Also|Brahmin Tamil}} |

|||

{{wikibooks|Brahmin Tamil}} |

|||

[[Tamil language|Tamil]] is the [[mother tongue]] of most Iyers residing in [[India]] and elsewhere. However, Iyers speak a distinct dialect of Tamil unique to their community.<ref name="ethnologue">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/14/show_language.asp?code=TCV|title=TAMIL: a language of India|accessdate=2008-09-03|year=2000|work=Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 14th Edition}}</ref><ref name="international_conference_on_dialects">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ifpindia.org/ecrire/upload/dialects_conference_note.pdf|title=Streams of Language: Tamil Dialects in History and Literature|accessdate=2008-09-03|publisher=french Institute of Pondicherry}}</ref><ref name="Tamil_dialects3">{{cite book | title=Negotiating multiculturalism: Disciplining Difference in Singapore | last=Purushotam| first=Nirmala Srirekham| pages=37|authorlink= |coauthors=| year=2000| publisher=Walter de Gruyter| location=}}</ref>This [[dialect]] of Tamil is known as [[Braahmik]] or [[Brahmin Tamil]], but is more popularly known by its [[colloquial]] term "Iyer baashai" or "language of Iyers". Brahmin Tamil is highly [[Sanskritized]] and has often invited ridicule from [[Tanittamil Iyakkam|Tamil]] [[nationalists]] due to its extensive usage of the Sanskrit [[vocabulary]]. However, with [[Brahmins]] moving out of their [[agraharams]] to urban centres or migrating to foreign countries, Brahmin Tamil is being increasingly discarded and is facing the prospect of [[extinction]]. The Palakkad Iyers have a unique sub-dialect of their own. Palakkad Tamil is characterized by the presence of a large number of words of Malayali origin. The Iyers of Tirunelveli speak a form of Tamil closely allied to the Tirunelveli dialect. The Sankheti Iyers speak a sub-dialect of Brahmin Tamil called [[Sankethi language|Sankheti]]. |

|||

Apart from Tamil, Iyers in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala are also fluent in the local languages of their state i.e. [[Telugu]], [[Kannada]] and [[Malayalam]], respectively. Iyers who reside in [[Mumbai]] and [[North India]] are well-versed in [[Hindi]] and [[English language|English]]. |

|||

Iyengars speak a separate dialect of Tamil called Iyengar Tamil. |

|||

==Iyers today== |

|||

[[Image:Tamil brahmin couple circa 1945.jpg|thumb|left|A Tamil Brahmin couple, circa 1945]] |

|||

Akin to Bengali Brahmins, the Brahmins of South India were one of the first communities to be Westernized. However, this was restricted to their outlook on the material world. They have retained their Smartha traditions despite almost two centuries of western influence<ref name="Tambram" />. |

|||

In addition to their earlier occupations, Iyers today have diversified into a variety of fields — their strengths particularly evident in the fields of [[Mass Media]], science, mathematics and computer science. It is a small percentage of Iyers who voluntarily choose, in this era, to pursue the traditional vocation of priesthood, though all Hindu temple priests are Brahmins. Some Iyers today have even married outside of their caste in Europe and therefore produced children of mixed background. |

|||

==Social and political issues== |

|||

''See Also:[[Iyer#Accusations of Casteism and Other Controversies|Accusations of Casteism and Other Controversies]] |

|||

[[Image:P. S.jpg|200px|This portrait of [[Sir P. S. Sivaswami Iyer]] depicts the grand and aristocratic lifestyle led by Tamil Brahmins during the [[British Raj]]|thumb|right]] |

|||

Since ancient times, Iyers, as members of the privileged priestly class, exercised a near-complete domination over [[educational]],[[religious]] and [[literary]] [[institutions]] in the Tamil country |

|||

<ref name="Vivekananda">{{cite book | title=The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda| last=Vivekananda| first=Swami| date=1955| pages=296| publisher=Advaita Ashrama}}</ref>. Their domination continued throughout the [[British Raj]] as they used their knowledge of the English language and education to dominate the political, administrative, [[judicial]] and [[intellectual]] spectrum. Upon India's independence in 1947, they hoped to consolidate their hold on the administrative and judicial machinery . Such a situation led to resentment from the other castes in Tamil Nadu; an upshot of this atmosphere was an "non-Brahmin" movement and the formation of the [[Justice Party (India)|Justice Party]]<ref name="Non-Brahmin Movement">{{Cite web|url=http://www.tamilnation.org/caste/nambi.htm|title=Caste & the Tamil Nation:The Origin of the Non-Brahmin Movement, 1905-1920|accessdate=2008-09-03|publisher=Koodal Publishers|year=1980|author=K. Nambi Arooran|work=Tamil renaissance and Dravidian nationalism 1905-1944}}</ref> . In the early days,the Justice Party functioned on a principled high-ground as a representative organization of non-Brahmins of the [[Madras Presidency]] and campaigning for their grievances to be addressed and for the fulfillment of their education and monetary needs. However, with the passage of time, the movement soon led to a power struggle between the [[Brahmin]]s and '''other upper castes''' like the [[Mudaliar]]s, [[Pillai]]s and [[Chettiar]]s. [[E.V.Ramasami Naicker|Periyar]], who took over as Justice Party President in the 1940s, changed its name to [[Dravidar Kazhagam|Dravida Kazhagam]], and formulated the view that [[Tamil Brahmins]] were [[Aryans]] as opposed to a majority of Tamils who were [[Dravidian]] based on [[Robert Caldwell]]'s writings <ref name="periyar_antibrahminism">{{cite news | last= Selvaraj| first= Sreeram | title= 'Periyar was against Brahminism, not Brahmins' | date=[[April 30]], [[2007]] | url =| work =Rediff News | accessdate = 2008-08-19}} |

|||

</ref>. See [[#Iyers and the Aryan Invasion Theory|Iyers and the Aryan Invasion Theory]]. The ensuing [[Anti-Brahminism|anti-Brahmin propaganda]] and the rising unpopularity of the [[Rajaji]] Government left an indelible mark on the Tamil Brahmin community ending their political aspirations forever. In the 1960s the [[Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam]] (roughly translated as "Organisation for Progress of Dravidians") and its subgroups gained political ground on this platform forming state ministries, thereby wrenching control from the [[Indian National Congress]], in which Iyers at that time were holding important party positions. Today, apart from a few exceptions, Iyers have virtually disappeared from the political arena. |

|||

<ref name="iyothee_thass">{{cite book | title=Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium: From Lyothee Thass to Periyar | last=Geetha| first=V.| date=2001| publisher=Bhatkal & Sen| id=ISBN 8185604371,ISBN 978-8185604374}}</ref><ref name="rise_of_caste">{{cite news | last= Lal| first= Amrith | title= Rise of caste in Dravida land | date=[[May 7]], [[2001]] | url =| work = Indian Express | accessdate = 2008-08-19}}</ref><ref>[http://www.outlookindia.com/full.asp?fodname=20050411&fname=Brahmins+(F)&sid=1 Dalits in Reverse, an article from Indian magazine ''The Outlook'']</ref><ref name="brahmnins-dalitsoftoday">{{cite news | last= Gautier| first= Francois | title= Are Brahmins the Dalits of today? | date=[[May 23]], [[2006]] | url =http://in.rediff.com/news/2006/may/23franc.htm | work =Rediff News | accessdate = 2008-08-19}}</ref><ref name="brahminsandeelamists">{{Cite web|url=http://www.ambedkar.org/News/hl/Brahmins%20and%20Eelamists.htm|title=Brahmins and Eelamists|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=ambedkar.org|author=V. Thangavelu}}</ref><ref name="Dalit_visions">{{cite book | title=Dalit Visions: The Anti-caste Movement and the Construction of an Indian Identity| last=Omvedt| first=Gail| year=2006| pages=95| publisher=Orient Longman| id=ISBN 8125028951, ISBN 9788125028956}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>Lloyd I. Rudolph Urban Life and Populist Radicalism: Dravidian Politics in Madras The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 3 (May, 1961), pp. 283-297</ref><ref> |

|||

Lloyd I. Rudolph and Suzanne Hoeber Rudolph, The Modernity of Tradition: political development in India P78,University of Chicago Press 1969, ISBN 0226731375 |

|||

</ref><ref>C. J. Fuller,The Renewal of the Priesthood: Modernity and Traditionalism in a South Indian Temple P117, Princeton University Press 2003 ISBN 0691116571 |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The recent decision by the Tamil Nadu government to appoint non-Brahmin priests in Hindu temples had created a controversy of sorts<ref name="tamil_nadu_caste_barrier">{{cite news | last= | first= | title= Tamil Nadu breaks caste barrier | date=[[May 16]], [[2006]] | url =http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4986616.stm | work =BBC News | accessdate = 2008-09-06}}</ref>, even leading to violence in the Nataraja temple at Chidambaram. <ref name="tension_at_chidambaram_temple">{{cite news | last= | first= | title= Tension at Chidambaram temple | date=[[March 2]], [[2008]] | url =http://news.webindia123.com/news/Articles/India/20080302/899005.html | work =Web India 123 | accessdate = 2008-09-06}}</ref> |

|||

== Criticism == |

|||

=== Relations with other communities === |

|||

''See Also: [[Brahminism]],[[Anti-Brahminism]],[[Reservations in India#Caste Based Reservations in Tamil Nadu|Caste-Based Reservations in Tamil Nadu]] |

|||

The legacy of Iyers have often been marred by accusations of [[racism]] and counter-racism against them by non-Brahmins and vice versa. The [[Manusmriti]] forbids Brahmins from eating with individuals of particular castes (particularly the [[Scheduled Castes]]) and prescribed a strict code of laws with regard to their day-to-day behavior and dealings with other castes. Iyers of orthodox families generally obeyed these laws strictly. |

|||

{{cquote|It was found that prior to Independence, the Pallars were never allowed to enter the residential areas of the caste Hindus particularly of the Brahmins. Whenever a Brahmin came out of his house, no Scheduled Caste person was expected to come in his vicinity as it would pollute his sanctity and if it happened by mistake, he would go back home cursing the latter. He would come out once again only after taking a bath and making sure that no such thing would be repeated. |

|||

However, as a mark of protest a few Pallars of this village deliberately used to appear before the Brahmin again and again. By doing so the Pallars forced the Brahmin to get back home once again to take a bath drawing water from deep well.<ref name="untouchability_indianvillages">{{Cite web|url=http://www.tamilnation.org/caste/ramaiah.htm#Untouchability_in_villages|title=Untouchability in villages|accessdate=2008-08-19|publisher=tamilnation.org|author=A. Ramiah|work=Untouchability and Inter Caste Relations in Rural India: The Case of Southern Tamil villages}}</ref>}} |

|||

[[T. Muthuswamy Iyer|Sir T. Muthuswamy Iyer]], the first Indian judge of the [[Madras High Court]], once made the controversially casteist remark: |

|||

{{cquote|Hindu temples were neither founded nor are kept up for the benefit of [[Muslim|Mahomedans]], [[Dalit|outcastes]] and others who are outside the scope of it<ref name="temple_entry">{{Cite web|url=http://www.evrperiyar-bdu.org/downloads/templeentry.pdf|title=THE RIGHT OF TEMPLE ENTRY|accessdate=2008-07-19|author=P. Chidambaram Pillai}}</ref>}} |

|||