Peter Sellers: Difference between revisions

Undid revision 502854815 by Schrodinger's cat is alive (talk) unexplained rm |

Undid revision 502855049 by Cardinal Direction (talk)Look at the previous two edits and you may guess where the information was. |

||

| Line 187: | Line 187: | ||

==Personal life== |

==Personal life== |

||

Sellers would claim that he had no personality and was almost unnoticeable, which meant that he "needed a strongly defined character to play".<ref>{{cite news|title=Obituary: Mr Peter Sellers|newspaper=[[The Times]]|date=25 July 1980|location=London|page=16}}</ref> He would make similar references throughout his life: when he appeared on ''[[The Muppet Show]]'' he chose not to appear as himself, instead appearing in a variety of costumes and accents. When [[Kermit the Frog]] told Sellers he could relax and be "himself," Sellers replied: |

|||

{{quote|But that, you see, my dear Kermit, would be altogether impossible. I could never be myself ... You see, there is no me. I do not exist ... There used to be a me, but I had it surgically removed.|Peter Sellers, ''The Muppet Show'', February 1978{{sfn|Sikov|2002|p=352}}}} |

|||

Others saw a different side to Sellers. Directors John and Roy Boulting considered that Sellers was "a deeply troubled man, distrustful, self-absorbed, ultimately self-destructive. He was the complete contradiction."<ref name=Boulting/> Sellers was shy and insecure when out of character.{{sfn|Lewis|1995|p=823}}<ref name="Mortimer (1980)"/> When he was invited to appear on [[Michael Parkinson]]'s [[Parkinson (TV series)|eponymous chat show]] in 1974, he withdrew the day before, explain to Parkinson that "I just can't walk on as myself". When he was told he could come on as someone else, he appeared dressed as a member of the [[Gestapo]].{{sfn|Parkinson|2009|p=255}} After a few lines in keeping with his assumed character, he stepped out of the role and settled down and, according to Parkinson himself, "was brilliant, giving the audience an astonishing display of his virtuosity".{{sfn|Parkinson|2009|p=256}} |

|||

Sellers' difficulties in his career and life prompted him to seek periodic consultations with astrologer [[Maurice Woodruff]], who held considerable sway over his later career.{{sfn|Sikov|2002|pp=117-118}} After a chance meeting with a North American Indian spirit guide in the 1950s, Sellers became convinced that the music hall comedian [[Dan Leno]], who died in 1904, haunted him and guided him into making career and life decisions.<ref>{{cite news|last=Evans|first=Peter|title=Dynamite in bed - and ruthless out of it. Lynne, the gold-digger who tricked Peter Sellers' family out of his millions|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-1225892/Dynamite-bed--ruthless-Lynne-gold-digger-tricked-Peter-Sellers-family-millions.html#comments|accessdate=26 June 2012|newspaper=[[Daily Mail]]|date=7 November 2009|location=London}}</ref>{{sfn|Anthony|2010|p=200}} |

|||

===Relationships=== |

===Relationships=== |

||

[[File:Britt Ekland and Peter Sellers 1964 crop.jpg|right|thumb|Sellers and Britt Ekland 1964]] |

[[File:Britt Ekland and Peter Sellers 1964 crop.jpg|right|thumb|Sellers and Britt Ekland 1964]] |

||

Revision as of 21:01, 17 July 2012

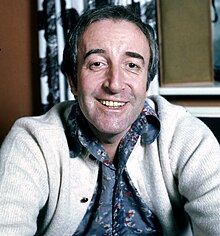

Peter Sellers | |

|---|---|

Publicity photo of Sellers, circa 1975 | |

| Born | Richard Henry Sellers 8 September 1925 |

| Died | 24 July 1980 (aged 54) London, England |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Occupation(s) | Radio and film actor and comedian |

| Years active | 1948–1980 |

| Known for | Impressionism |

| Notable work | The Pink Panther, Dr. Strangelove, Lolita, Being There |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Hayes (1951–61; divorced) Britt Ekland (1964–68; divorced) Miranda Quarry (1970–74; divorced) Lynne Frederick (1977–80; his death) |

| Awards | Golden Globe for Best Actor in Being There (1980); BAFTA (1959) |

| Website | http://www.petersellers.com |

Richard Henry Sellers, CBE (8 September 1925 – 24 July 1980), known as Peter Sellers, was a British comedian, singer and actor who was perhaps best known as Chief Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther series of films. He is also notable for his appearences in the BBC Radio comedy series The Goon Show and for his many comic songs which he performed frequently during his 50-year career.

Born in Portsmouth, Sellers made his stage debut at the Kings Theatre, Southsea, during his infant years and later appeared at the Windmill Theatre. Sellers began accompanying his parents in a variety act which toured the provincial theatres. His theatrical abilities were dismissed by his father but encouraged by his mother and he later built on his abilities as an improvisational performer whilst attending college in his teenage years. Sellers became interested in stand-up comedy, but was initially unsuccessful and so planned on a performing career on radio. In 1948 his made his radio debut in Much Binding in the Marsh eventually becoming a regular radio performer, appearing in Starlight Hour, The Gang Show, Henry Hall's Guest Night and It's Fine To Be Young.

During the early 1950s, Sellers, along with Michael Bentine, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe, took part in a series of recordings known as the Goon Show; a collaboration which ended in 1960. His ability to speak in different accents along with his talent to portray a wide range of characters to comic effect, contributed to his success as a radio personality and screen actor and earned him national and international nominations and awards.

In the 1950s, Sellers began to appear in films and scored some considerable success with his roles. His film output was frequent and he displayed a versatile ability to perform in different film genres. Perhaps the most famous of these were The Pink Panther series of films, Dr. Strangelove, Lolita and Being There. Actress Bette Davis once remarked of him, "He isn't an actor—he's a chameleon."[1] Despite his professional success, Sellers struggled with depression and his behaviour was famously erratic. Sellers' private life was characterised by turmoil and crises, and included emotional problems and substance abuse. Sellers was married four times, and had three children from the first two marriages. He died as a result of heart disease in 1980.

Biography

Family background and early life

Sellers was born on 8 September 1925 in Southsea, a suburb of Portsmouth. His parents were Yorkshire-born William "Bill" Sellers (1900—1962), and Agnes Doreen "Peg" (née Marks) (1892—1967); both were variety entertainers, with Peg being one of the Ray Sisters troupe.[2] Although he was christened Richard Henry, his parents always called him Peter, after his elder stillborn brother;[3] aside from the stillborn child, Sellers was an only child.[4] Peg Sellers was related to the pugilist Daniel Mendoza (1764–1836),[nb 1] a relative Sellers greatly revered, and whose engraving hung in Sellers' office. At one time Sellers planned to have Mendoza's image for his production company's logo.[6]

Sellers' stage debut was aged two weeks, when he was carried on stage by Dickie Henderson, the headline act at the Kings Theatre, Southsea: the crowd sang "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow" and Sellers burst into tears.[7] With both his parents in variety, the family constantly on the move, touring with theatre commitments and Sellers was unhappy, saying "I really didn't like that period of my life as a kid".[8]

Sellers had a very close relationship with his mother; his friend Spike Milligan considered that "it really is unhealthy for a grown man to be so needful of his mother".[9] Sellers' agent, Dennis Selinger, recalled his first meeting with Peg and Peter Sellers, noting that "Sellers was an immensely shy young man, inclined to be dominated by his mother, but without resentment or objection".[10] Sellers' biographer, Ed Sikov, considered this influence to be more insidious, seeing Sellers to be "the painstaking product of a terrible mother, the fucked-up labour of her love."[11]

Schooling

In 1935 the Sellers family settled in North London, initially in a flat in Muswell Hill.[12] Although Bill Sellers, was Protestant, and Peg was Jewish, Sellers attended the North London Roman Catholic school St. Aloysius College, run by the Brothers of Our Lady of Mercy.[2] According to Sellers' biographer, Roger Lewis, Sellers was intrigued by Catholicism, but soon after entering Catholic school, he "discovered he was a Jew—he was someone on the outside of the mysteries of faith."[13] He was a top student at the school, and recalls that the teacher once scolded the other boys for not studying: "The Jewish boy knows his catechism better than the rest of you!"[14]

Later in his life, Sellers is quoted as saying "My father was solid Church of England but my mother was Jewish, Portuguese Jewish, and Jews take the faith of their mother."[13] Film critic Kenneth Tynan noted after his interview with Sellers that one of the main "motive forces" for his ambition as an actor was "his hatred of anti-Semitism." Tynan explained that while Jewishness is "tolerated" in some professions, it was often not in actors. This led to Sellers' refusal "to be content with the secure reputation of a great mimic and his determination to go down in history as something more—a great actor, perhaps, or a great director".[15] Sellers was of the opinion that "becoming part of some large group never does any good. Maybe that's my problem with religion," he said during an interview. He explained that "I wasn't baptised. I wasn't Bar Mitzvahed. I suppose my basic religion is doing unto others as they would do unto me. But I find it all very difficult. I am more inclined to believe in the Old Testament than in the New".[16]

Early experiences of performance

Accompanying his family on the variety show circuit,[17] Sellers learned stagecraft, which proved valuable later. He performed at age five at the burlesque Windmill Theatre in the drama Splash Me!, which featured his mother.[18] However, he grew up with conflicting influences from his parents and developed ambivalent feelings about show business. His father lacked confidence in Peter's abilities to ever become much in the entertainment field, even suggesting that his son's talents were only enough to become a road sweeper, while Sellers' mother encouraged him continually.[19]

Whilst at St Aloysius College Sellers began to develop his improvisational skills. Sellers and his closest friend at the time, Bryan Connon, both enjoyed listening to early radio comedy shows and Connon remembers that "Peter got endless pleasure imitating the people in Monday Night at Eight. He had a gift for improvising dialogue. Sketches, too. I'd be the 'straight man', the 'feed', ... I'd cue Peter and he'd do all the radio personalities and chuck in a few voices of his own invention as well."[20]

With the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, St Aloysius College was evacuated to Cambridgeshire, but Peg decided not to allow Sellers to go,[21] a decision which ended his formal education aged fourteen.[2] Early in 1940 Peg decided to move to the north Devon town of Ilfracombe, where her brother managed the Victoria Palace Theatre;[21] Sellers got his first job at the theatre aged fifteen, starting as a caretaker.[22] He was steadily promoted, becoming a box office clerk, usher, assistant stage manager and lighting operator. He was also offered some small acting parts.[22] Working backstage gave him a chance to see serious actors at work, such as Paul Scofield. He also became close friends with Derek Altman, and together they launched Sellers' first stage act under the name "Altman and Sellers," where they played ukuleles, sang, and told jokes. They also both enjoyed reading detective stories by Dashiell Hammett, and were inspired to start their own detective agency. "Their enterprise ended abruptly when a potential client ripped Sellers' fake moustache off."[22]

At his regular job backstage at the theatre, Sellers began practising on a set of drums that belonged to the band "Joe Daniels and His Hot Shots." Daniels noticed his efforts and gave him practical instructions. Sellers' biographer Ed Sikov wrote that "drumming suited him. Banging in time Pete could envelop himself in a world of near-total abstraction, all in the context of a great deal of noise."[23] Spike Milligan later noted that Sellers was very proficient on the drums and "might well have stayed a jazz drummer" if his mimicry and improvisation skills had not been so good.[2]

Second World War

As the Second World War broke out in Europe, Sellers continued to develop his drumming skills, and he joined the bands of Oscar Rabin, Henry Hall and Waldini and his Gypsy Band,[9] as well as his father's quartet, before he left and joined a band from Blackpool.[24] In the latter two of these bands, Sellers was a member of Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA), the organisation that provided entertainment for British forces and factory workers during the war.[24]

In September 1943 he joined the Royal Air Force, although it is unclear whether he volunteered or was enlisted;[25][26] his mother tried to have him disqualified on medical grounds, but failed.[2] Although Sellers wished to become a pilot, his poor eyesight meant he was restricted to ground staff duties only.[27] He found the duties dull and auditioned for Ralph Reader to become a member of his Gang Shows: Reader accepted him and Sellers toured the UK before being transferred to India.[28] His tour also included Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Burma, although the duration of his stay in Asia is unknown and its length may have been exaggerated by Sellers himself.[29] He also served in Germany and France after the war.[29]

Another Gang Show player, actor David Lodge became friends with Sellers and described Sellers' role, saying "Peter on the drums was one of the best performers ever. "Drumming Man" was how he was billed. He closed the show. To see him do his jazz numbers was a show in itself, throwing up the sticks, catching them. Nothing could have followed him!"[30] Occasionally Sellers impersonated his superiors by bluffing his way into the Officers' Mess using mimicry and make-up. Lodge clearly remembers the first time he witnessed Sellers impersonating an officer, after he pulled a squadron leader's uniform out of the props. The band's trumpeter first tried to stop him: "I noticed his walk had even gotten years older, and carried an authority I never imagined Peter could muster. He threw open the door of the men's bunkhouse and waited a second before he entered—even then he had a great sense of timing ... Then he walked down the centre, eyeing them with quiet pride ... imitating impeccably the tones of a man unused to having his authority questioned."[31]

Early post-war career

After the war, Sellers returned to England to work at the Air Ministry[32] prior to his demobilisation, which came in 1946.[33] Sellers had difficulty in finding bookings and work was sporadic.[34] He was fired after one performance of stand-up comedy routine in Peterborough, but the headline act, Welsh vocalist Dorothy Squires, took pity on him and persuaded the management to reinstate him.[35] Sellers was also continuing his drumming and was billed on his appearance at the Aldershot Hippodrome as "Britain's answer to Gene Krupa".[34] In March 1948, Sellers gained a slot at the Windmill Theatre, a variety and revue theatre in London; he provided the comedy turns in between the nude shows on offer.[36] Sellers undertook a six-week run at the theatre, earning £30 a week (£1,378 in 2024 pounds[37]).[38]

In 1948 Sellers wrote to the BBC, then based at Alexandra Palace, and subsequently received an audition. As a result he made his television debut on 18 March 1948 in New To You, with an act that was largely based on impressions; he was well received and returned to appear the following week.[39]

Frustrated with the slow development of his career, Sellers telephoned BBC radio producer Roy Speer, pretending to be Kenneth Horne, star of the radio show Much Binding in the Marsh, to get Speer to speak to him. Speer called Sellers a "cheeky young sod" for his efforts, but he was given an audition as a result, which initially led to a brief appearance on 1 July 1948 on ShowTime[40] and subsequently to his work on Ray's a Laugh with comedian Ted Ray.[41] By the end of October 1948 Sellers was a regular radio performer, appearing in Starlight Hour, The Gang Show, Henry Hall's Guest Night and It's Fine To Be Young.[42]

In December 1948 the BBC Third Programme broadcast the comedy series Third Division, which starred Benny Hill, Harry Secombe, Carole Carr, Michael Bentine and Sellers, with scripts provided by Frank Muir and Denis Norden.[43] One evening Sellers and Bentine visited the Hackney Empire, where Secombe was performing, and Bentine introduced Sellers to Spike Milligan.[44] The four would meet up at Grafton's public house near Victoria, where the owner, Jimmy Grafton was also a BBC script writer; the four comedians dubbed him KOGVOS (King of Goons and Voice of Sanity) and he went on to edit some of the first Goon Shows.[45]

1950s

Sellers had his first inclusion in a film in 1950, dubbing the voice of Alfonso Bedoya in The Black Rose.[46] He continued to work with Secombe, Bentine and Milligan; from their first meeting the four tried to interest the BBC in their work, but it was not until 3 February 1951 that they made a trial tape for BBC producer Pat Dixon, which was eventually accepted. The first Goon Show[45] was broadcast on 28 May 1951[47] under the name Crazy People—against the wishes of the Goons themselves.[4] Sellers appeared in all The Goons for all ten series, the programme finishing on 28 January 1960.[45]

In 1949 Sellers had started to date Anne Howe,[48][nb 2] and he proposed to her in April 1950.[50] The couple married at Caxton Hall in London on 15 September 1951,[51] and their son, Michael, was born on 2 April 1954,[52] with a daughter, Sarah, following in 1958.[53]

He continued with his attempts to move into film with a number of small roles, before being offered a role in the 1955 Ealing Comedies film, The Ladykillers as Harry Robinson, the teddy boy. Sellers played opposite Alec Guinness, Herbert Lom and Cecil Parker and this was seen to be his "first good role".[54] The Ladykillers was a success in both Britain and the US and it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay at the 29th Academy Awards.[55]

No further film work was available for Sellers immediately after the film, so, in 1956, The Goons ran three series on Britain's new television station, ITV. The three series, The Idiot Weekly, Price 2d, A Show Called Fred and Son of Fred.[56] Film producer Michael Relph was impressed with one of Sellers' portrayals of an elderly character in Idiot Weekly, he cast the 32-year-old actor as a 68-year-old projectionist in The Smallest Show on Earth.[57]

Sellers' difficulties in his career and life prompted him to seek periodic consultations with astrologer Maurice Woodruff, who held considerable sway over his later career.[58] After a chance meeting with a North American Indian spirit guide in the 1950s, Sellers became convinced that the music hall comedian Dan Leno, who died in 1904, haunted him and guided him into making career and life decisions.[59][60]

Sellers released his first album in 1958, The Best of Sellers, which reached number 3 in the UK Albums Chart;[61] the record was produced by George Martin and released on Parlophone.[62]

Sellers also made his first film with John and Roy Boulting in 1958, Carlton-Browne of the F.O., playing a support role for the film's lead, Terry-Thomas.[63] Before the film had been released the Boultings, with Sellers and Terry-Thomas in the cast, started filming I'm All Right Jack.[63] When he first saw the script, Sellers turned the role down, asking "Where are the funny lines?"[64] After a week of discussion and persuasion he agreed to take the role of Fred Kite, a shop steward;[64] Sellers prepared for the role by watching footage of union officials, but was still unsure whether his characterisation would be humorous[65] until his screen test was met with laughter and spontaneous applause from the crew.[66] Sellers won the Best British Actor at the 13th British Academy Film Awards for his portrayal of Kite;[67] the film became the biggest box office hit in Britain of 1960.[68]

In between Carlton-Browne of the F.O. and I'm All Right Jack, Sellers also starred in The Mouse That Roared; he played three leading and distinct roles: the elderly queen, the ambitious Prime Minister and the innocent and clumsy farm boy selected to lead an invasion of the United States.[69]

After completing I'm All Right Jack, Sellers returned to record a new series of The Goon Show.[70] Over the course of two weekends he took his 16mm cine camera to Totteridge Lane in London and filmed himself, Spike Milligan Mario Fabrizi, Leo McKern and Richard Lester. Lester also helped with the editing and the result was The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film, an eleven minute short film which was only meant for showing amongst friends.[71] Instead the film was screened at the 1959 Edinburgh and San Francisco film festivals,[72]winning the award for best fiction short in the latter festival. The film was then nominated for an Academy Award for Short Subject (Live Action) at the 1960 Academy Awards.[73]

1959 also saw Sellers release his second album, Songs For Swinging Sellers, which reached number 3 in the UK Albums Chart.[61]

1960s

In 1960 Fleming portrayed an Indian doctor, Dr. Ahmed el Kabir, in The Millionairess with Sophia Loren. The film was based on a George Bernard Shaw play of the same name; Sellers was not interested in taking the role until he learnt that Loren was to be his co-star.[74] When asked about his glamorous co-star, he explained to reporters "I don't normally act with romantic, glamorous women ... she's a lot different from Harry Secombe."[75] Sellers and Loren developed a close relationship during filming, with Sellers declaring his love for her, even in front of his wife;[76] Sellers went as far as to wake his son at 3am to ask "Do you think I should divorce your mummy?"[77][nb 3]

The film inspired the George Martin-produced novelty hit single with Sellers and Loren, Goodness Gracious Me, which reached number 4 in the UK Singles Chart in November 1960.[79] A follow-up single by the couple, Bangers and Mash, reached number 22 in UK chart.[79] The songs were included on an album released by the couple, Peter & Sophia, which reached number 5 in the UK Albums Chart.[61]

In 1961 Sellers directed his first film, in which he also starred: Mr. Topaze,[80] based on the Marcel Pagnol play Topaze.[81] The public reaction to the film was mediocre,[82] and Sellers rarely referred to the film again.[83]

In 1962, Stanley Kubrick asked Sellers to play the role of Clare Quilty in Lolita, opposite James Mason and Shelley Winters.[84] According to Alexander Walker, working on Lolita was "the first time he tasted what it was like to work creatively during shooting, not just in the preproduction run-up."[85] Sellers felt the part of a flamboyant American television playwright was beyond his ability, mainly because Quilty was, in Sellers' words, "a fantastic nightmare, part homosexual, part drug addict, part sadist".[86] He became nervous about taking on the role, and many people came up to him and told him they felt the role believable.[87] Kubrick eventually succeeded in persuading Sellers to play the part. Kubrick had American jazz producer Norman Granz record Sellers' portions of the script for Sellers to listen to, so he could study the voice and develop confidence.[88]

Unlike most of his earlier well-rehearsed film roles, Sellers was encouraged by Kubrick to improvise throughout the filming in order to exhaust all the possibilities of his character. In order to capture Sellers in the shortest number of takes, Kubrick often used as many as three cameras.[89] Kubrick later described the filming process: "When Peter was called to the set he would usually arrive walking very slowly and staring morosely ... As work progressed, he would begin to respond to something or other in the scene, his mood would visibly brighten and we would begin to have fun. Improvisational ideas began to click and the rehearsal started to feel good. On many of these occasions, I think, Peter reached what can only be described as a state of comic ecstasy."[89] Kubrick gave him free "license" to break the rules and Sellers "indulged in his liking for setting himself problems, encouraged by Kubrick to explore the outer limits of the comédie noire—and sometimes, he felt, go over them—in a way that appealed to the macabre imagination of himself and his director."[89] Oswald Morris, the film's cinematographer, further commented that, "the most interesting scenes were the ones with Peter Sellers, which were total improvisations."[90] Because of this experience, Sellers later claimed that his relationship with Kubrick became one of the most rewarding of his career.[91]

At the end of 1962 his marriage to Anne finally disintegrated,[92][nb 4] and in October Sellers' father Bill died, aged sixty-two.[94] After the death, Sellers decided to get away from England and take the first international film he could; he took roles in Heavens Above! and The Wrong Arm of the Law before an international offer came in for The Pink Panther.[95]

Edwards' last minute offer for the role of Chief Inspector Jacques Clouseau was prompted by the decision of Peter Ustinov to suddenly back out of the film;[96] Edwards later recalled his feelings as "desperately unhappy and ready to kill, but as fate would have it, I got Mr. Sellers instead of Mr. Ustinov—thank God!"[97] The film starred David Niven in the principal role, with two others actors in more prominent roles that Sellers,[98] but Sellers' performance is "his first memorable performance as a visual screen comic in the Chaplin-Keaton tradition and class."[98] Although the Clouseau character was in the script, Sellers created the personality. While flying to Rome for filming, he used the time alone to devise the character, including the accent, costume and make-up for the part, including a moustache and trench coat.[99] Sellers described the character's personality he would portray:

I'll play Clouseau with great dignity, because he thinks of himself as one of the world's best detectives. Even when he comes a cropper, he must pick himself up with that notion intact. The original script makes him out to be a complete idiot. I think a forgivable vanity would humanize him and make him kind of touching. It's as if filmgoers are kept one fall ahead of him.[99]

The Pink Panther was not released until January 1964[100] when it received only a lukewarm reception from the critics.[101]

In Kubrick's next film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb he asked Sellers to be in the leading role. Sellers played three extremely different characters: U.S. President Merkin Muffley, Dr. Strangelove, a heavily German-accented nuclear scientist, and Group Captain Lionel Mandrake of the RAF. Sellers was initially hesitant about taking on the task, but Kubrick convinced him that there was no better actor that could play these parts.[102]

Muffley and Dr. Strangelove appeared in the same room throughout the film, with the help of doubles mostly seen from the rear. Sellers was originally also cast to play a fourth role as bomber pilot Major T. J. "King" Kong, but from the beginning Sellers was reluctant. He felt his workload was too heavy and he worried he would not properly portray the character's Texas accent. Kubrick pleaded with him and asked screenwriter Terry Southern (who had been raised in Texas) to record a tape with Kong's lines spoken in the correct accent. Using Southern's tape, Sellers managed to get the accent right, and started shooting the scenes in the airplane. But then Sellers sprained an ankle and could not work in the cramped cockpit set.[103][104] This forced Kubrick to recast the part with Slim Pickens. For his performance in all three roles, Sellers was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor. Kubrick again gave Sellers a free rein to improvise throughout the filming. Sellers once said, "If you ask me to play myself, I will not know what to do. I do not know who or what I am."[105]

In early 1964, at age 38, Sellers suffered a series of eight heart attacks over the course of three hours[106][107] after visiting Disneyland with his family. His health meant he had to withdraw from the filming of Billy Wilder's Kiss Me, Stupid and he was replaced by Ray Walston. Although Sellers survived, his heart was permanently damaged. Sellers chose to consult with psychic healers rather than seek conventional Western medical treatment, and his heart condition continued to deteriorate over the next 16 years. In late 1977, he suffered a second major heart attack, resulting in his being fitted with a pacemaker.[108]

1970s

Sellers appeared in an episode of the American television series It Takes a Thief in 1969. Fellow comedian and friend Spike Milligan noted that the early 1970s were for Sellers "a period of indifference, and it would appear at one time that his career might have come to a conclusion",[2] although the subsequent Pink Panther films reinvigorated his career and made him a millionaire.[2]

Directors John and Roy Boulting considered that Sellers was "a deeply troubled man, distrustful, self-absorbed, ultimately self-destructive. He was the complete contradiction."[64] Sellers was shy and insecure when out of character.[109][110] When he was invited to appear on Michael Parkinson's eponymous chat show in 1974, he withdrew the day before, explain to Parkinson that "I just can't walk on as myself". When he was told he could come on as someone else, he appeared dressed as a member of the Gestapo.[111] After a few lines in keeping with his assumed character, he stepped out of the role and settled down and, according to Parkinson himself, "was brilliant, giving the audience an astonishing display of his virtuosity".[112]

He returned to the character for three more sequels from 1975 to 1978. The Trail of the Pink Panther, containing unused footage of Sellers, was released in 1982, after his death. His widow, Lynne Frederick, successfully sued the film's producers for unauthorised use. Sellers had prepared to star as Chief Inspector Clouseau in another Pink Panther film; he died before the start of this project, Romance of the Pink Panther.

Sellers would claim that he had no personality and was almost unnoticeable, which meant that he "needed a strongly defined character to play".[113] He would make similar references throughout his life: when he appeared on The Muppet Show he chose not to appear as himself, instead appearing in a variety of costumes and accents. When Kermit the Frog told Sellers he could relax and be "himself," Sellers replied:

But that, you see, my dear Kermit, would be altogether impossible. I could never be myself ... You see, there is no me. I do not exist ... There used to be a me, but I had it surgically removed.

— Peter Sellers, The Muppet Show, February 1978[114]

In 1979, Sellers played the role of Chance, a simple-minded gardener addicted to watching TV, in the black comedy Being There, considered by some critics to be the "crowning triumph of Peter Sellers's remarkable career,"[115] as well as a great achievement for novelist Jerzy Kosinski. During a BBC interview in 1971, Sellers said that more than anything else, he wanted to play the role of Chance.[115]

Kosinski, the book's author, felt that the novel was never meant to be made into a film, but Sellers succeeded in changing his mind, and Kosinski allowed Sellers and director Hal Ashby to make the film, provided he could write the script.[115] According to film critic Danny Smith, Sellers was "naturally intrigued with the idea of Chance, a character who reflected whatever was beamed at him".[115]

Sellers's performance was praised by some critics as achieving "the pinpoint-sharp exactitude of nothingness. It is a performance of extraordinary dexterity",[116] and "[making] the film's fantastic premise credible".[117]

Sellers's described his experience of working on the film as "so humbling, so powerful"[118] During the filming, in order not to break his character, he refused most interview requests, and even kept his distance from other actors. He tried to remain in character even after he returned home.[118] Sellers considered Chance's walking and voice the character's most important attributes, and in preparing for the role, Sellers worked alone with a tape recorder, or with his wife, and then with Ashby, to perfect the clear enunciation and flat delivery needed to reveal "the childlike mind behind the words."[118]

Critic Frank Rich noted the acting skill required for this sort of role, with a "schismatic personality that Peter had to convey with strenuous vocal and gestural technique ... A lesser actor would have made the character's mental dysfunction flamboyant and drastic ... [His] intelligence was always deeper, his onscreen confidence greater, his technique much more finely honed."[117]

Co-star Shirley MacLaine found Sellers "a dream" to work with, while the story's author and screenwriter Jerzy Kosinski claimed that "nobody thought Chance was even a character, yet Peter knew that man."[119] Being There earned Sellers his best reviews since the 1960s, a second Academy Award nomination and a Golden Globe award. A few months after the film was released, Time magazine wrote a cover-story article about Sellers, entitled, "Who is This Man?" The cover showed many of the characters Sellers had portrayed, including Chance, Quilty, Strangelove, Clouseau, and the Grand Duchess Glorianna XII. Sellers was pleased by the article, written by critic Richard Schickel, and wrote an appreciative letter to the magazine's editor.[120]

1980s

Sellers' last movie was The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, a comedic reimagining of the classic series of adventure novels by Sax Rohmer. In this new version, Sellers played both "Fu Manchu" and his arch nemesis, police inspector Nayland Smith. Production of the film ran into problems from the start, with Sellers' poor health and mental instability causing long delays and bickering between star and director Piers Haggard. With roughly 60% of the movie shot, Sellers had Haggard sacked and took over direction himself. Haggard later complained that the reshoots Sellers ordered added nothing to the production, and had resulted in the film being incoherent and unfocused.

Sellers died shortly before Fu Manchu was released, with his very last performance being that of conman "Monty Casino" in a series of adverts for Barclays Bank. In 1982, Sellers returned to the big screen as Inspector Clouseau in Trail of the Pink Panther, which was composed entirely of deleted scenes from his past three Panther movies, in particular The Pink Panther Strikes Again, with a new story written around them. David Niven also reprised his role of Sir Charles Lytton in this movie. Along with what many, notably his widow Lynne Frederick, saw as exploitation of Sellers, the manner in which Niven's cameo was handled has earned the movie a lasting unsavoury reputation.[citation needed] Edwards continued the series with a further instalment called the Curse of the Pink Panther, which was shot back-to-back with the framing footage for Trail, but Sellers was wholly absent from this film.

After The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, Sellers was scheduled to appear in another Clouseau comedy, The Romance Of The Pink Panther. Its script, written by Peter Moloney and Sellers himself, had Clouseau falling for a brilliant female criminal known as 'The Frog' and aiding her in her heists with the aim to reform her character.[citation needed] Blake Edwards did not participate in the planning of this new Clouseau instalment, as the working relationship between him and Sellers had broken down during the filming of Revenge Of The Pink Panther. The final draft of the script, including a humorous cover letter signed by "Pete Shakespeare", was delivered to United Artists' office less than six hours before Sellers died.[citation needed] Sellers' death ended the project, along with two other planned movies for which Sellers had signed contracts in 1980. The two films—Unfaithfully Yours and Lovesick—were rewritten as vehicles for Dudley Moore; both performed poorly at the box office upon release.[citation needed] Trade papers such as Variety carried an elaborately curlicued advert for the former movie, with Sellers at the top of the cast list, in early June 1980.[citation needed]

Death

Photograph by Allan Warren

A reunion dinner was scheduled in London with his Goon Show partners, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe, for 25 July 1980. But around noon on 22 July, Sellers collapsed from a massive heart attack in his Dorchester Hotel room and fell into a coma. He died in Middlesex Hospital, London just after midnight on 24 July 1980, aged 54.[122] He was survived by his fourth wife, Lynne Frederick, and his three children. At the time of his death, he was scheduled to undergo heart surgery at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.[123]

Although Sellers was reportedly in the process of excluding Frederick from his will a week before he died, she inherited almost his entire estate worth an estimated £4.5 million while his children received £800 each.[124] When Frederick died in 1994 (aged 39), her mother Iris inherited everything, including all of the income and royalties from Sellers' work. When Iris dies the whole estate will go to Cassie, the daughter Lynne had with her third husband, Barry Unger. Sellers' only son, Michael, died of a heart attack at 52 during surgery on 24 July 2006 (26 years to the day after his father's death).[125] Michael was survived by his second wife, Alison, whom he married in 1986, and their two children.

In his will, Sellers requested that the Glenn Miller song "In the Mood" be played at his funeral. The request is considered his last touch of humour, as he hated the piece.[126] His body was cremated and he was interred at Golders Green Crematorium in London. After her death in 1994, the ashes of his former widow Frederick were co-interred with his.[124]

Acting technique and preparation

Sellers' friend and Goon Show colleague Spike Milligan said that Sellers "had one of the most glittering comic talents of his age",[2] while John and Ray Boulting noted that he was "the greatest comic genius this country has produced since Charles Chaplin".[64] In an October 1962 interview for Playboy, Sellers described how he prepared for his wide range of roles:

I start with the voice. I find out how the character sounds. It's through the way he speaks that I find out the rest about him. ... After the voice comes the looks of the man. I do a lot of drawings of the character I play. Then I get together with the makeup man and we sort of transfer my drawings onto my face. An involved process. After that I establish how the character walks. Very important, the walk. And then, suddenly, something strange happens. The person takes over. The man you play begins to exist.[16]

Writer and playwright John Mortimer saw the process for himself when Sellers was about to undertake filming on Mortimer's The Dock Brief and could not decide how to play the character of the barrister. By chance he ordered cockles for lunch and the smell brought back a memory of the seaside town of Morecambe: this gave him "the idea of a faded North Country accent and the suggestion of a scrappy moustache".[110] So important was the voice as the starting point for character development Sellers would walk round London with a reel-to-reel tape recorder, recording voices to study at home.[127]

A feature of the characterisations undertaken by Sellers is that regardless of how clumsy or idiotic they are, he ensured they always retain their dignity.[41] On playing Clouseau, he described that "I set out to play Clouseau with great dignity because I feel that he thinks he is probably one of the greatest detectives in the world. The original script makes him out to be a complete idiot. I thought a forgivable vanity would humanise him and make him kind of touching.[128] His biographer, Ed Sikov notes that because of this retained dignity, Sellers is "the master of playing men who have no idea how ridiculous they are.[129] Film critic Dilys Powell also saw the inherent dignity in the parts and noted that Sellers had a "balance between character and absurdity".[130] Fellow actor Richard Attenborough also thought that because of his sympathy, Sellers could "inject into his characterisations the frailty and substance of a human being".[131] Critic Tom Milne saw a change over Sellers' career and noted that his "comic genius as a character actor was ... stifled by his elevation to leading man" and his later films suffered as a result.[132]

Personal life

Relationships

Sellers' personality was described by others as difficult and demanding and he often clashed with fellow actors and directors.[132] He had a strained relationship with friend and director Blake Edwards, with whom he worked on the Pink Panther series and The Party. The two sometimes stopped speaking to each other during filming, communicating by passing each other notes.[133] Steven Bach, the senior vice-president and head of worldwide productions for United Artists considered that Sellers was "deeply unbalanced, if not committable: that was the source of his genius and his truly quite terrifying aspects as manipulator and hysteric".[134] Sellers' difficulties to maintain civil and peaceful relationships also extended into his private life. He assaulted his then wife, Britt Ekland.[135].

Marriages

Sellers was married four times and fathered three children:

- Anne Hayes (née Howe,[136] 1951–1961). They had a son, Michael, and a daughter, Sarah.

- Swedish actress Britt Ekland (1964–1968). They had a daughter, Victoria Sellers. The couple appeared in three films together: Carol For Another Christmas (1964), After the Fox (1966), and The Bobo (1967).

- Australian model Miranda Quarry (1970–1974); now the Countess of Stockton.

- English actress Lynne Frederick (1977–1980), who was briefly married to Sir David Frost shortly after Sellers' death.

Filmography and other works

Legacy and influence

The stage play, "Being Sellers," premiered in Australia in 1998, three years after release of the biography by Roger Lewis, "The Life and Death of Peter Sellers." The play premiered in New York in December 2010. In 2004, the book was turned into an HBO film, The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, starring Geoffrey Rush.[137]

The film Trail of the Pink Panther, made by Blake Edwards using unused footage of Sellers from The Pink Panther Strikes Again, is dedicated to Sellers's memory. The title reads "To Peter ... The one and only Inspector Clouseau."

In a 2005 poll to find "The Comedian's Comedian", Sellers was voted 14 in the list of the top 20 greatest comedians by fellow comedians and comedy insiders.[138] British comedian Sacha Baron Cohen frequently referred to Peter Sellers "as the most seminal force in shaping his early ideas on comedy". Cohen was considered for the role of the biopic The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, although the role eventually went to Geoffrey Rush.[139]

References

- Notes

- ^ Accounts vary as to whether Agnes was a first cousin, three times removed, of Mendoza,[5] or if she was his great-granddaughter.[6]

- ^ Her maiden name was Anne Howe, while her professional name was Anne Hayes.[49]

- ^ There is uncertainty if the relationship was anything more than platonic: a number of people, including Spike Milligan, consider it was an affair, whilst others, including Graham Stark, think it remained nothing more than a a strong friendship. Sellers' wife at the time, Anne, afterwards commented that "I don't know to this day whether he had an affair with her. Nobody does."[78]

- ^ The decree nisi was granted in March 1963 and Anne married Ted Ledy in October the same year.[93]

- Footnotes

- ^ Peter Sellers Bio, Turner Classic Movies

- ^ a b c d e f g h Millian, Spike (2004). "Sellers, Peter (1925–1980)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31669. Retrieved 9 July 2012. (subscription required) Cite error: The named reference "Milligan (DNB)" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 5.

- ^ a b Lewis 1995, p. 690.

- ^ "Peg Sellers". Find A Grave. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b Lewis 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 19.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 9.

- ^ a b Evans 1980, p. 45.

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 57.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 24.

- ^ a b Lewis 1995, p. 44.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 12.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Playboy interview: Peter Sellers". Playboy. 9 (10): 72. 1 October 1962.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 8.

- ^ Louvish, Simon (5 October 2002). "Here, there and everywhere". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 18.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 28.

- ^ a b Walker 1981, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Sikov 2002, p. 19.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 20.

- ^ a b Sikov 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 40.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 25.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 42.

- ^ a b Sikov 2002, p. 26.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 44.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 46.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 32.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 132.

- ^ a b Sikov 2002, p. 38.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 57.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 58.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 40.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, pp. 47–4.

- ^ a b Lewis 1995, p. 164.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 46.

- ^ Carpenter 2003, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Barker, Dennis. "Goons (act. 1951–1960)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 July 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 284.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 177.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 230.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 231.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 57.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 71.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 98.

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 79.

- ^ "The 29th Academy Awards (1957) Nominees and Winners". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Sikov 2002, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Evans, Peter (7 November 2009). "Dynamite in bed - and ruthless out of it. Lynne, the gold-digger who tricked Peter Sellers' family out of his millions". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Anthony 2010, p. 200.

- ^ a b c "Peter Sellers, albums". Official UK Charts Archive. The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 186.

- ^ a b Sikov 2002, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d Boulting, John; Boulting, Roy (25 July 1980). "Peter the Great". The Guardian. London. p. 11.

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 85.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 80.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards 1959". BAFTA Awards Database. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 536.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 594.

- ^ Sikov 2002, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Oliver, John. "Running, Jumping and Standing Still Film, The (1960)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "The 32nd Academy Awards (1960) Nominees and Winners". Oscar Legacy. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 141.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 84.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Sellers 1981, p. 72.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 145.

- ^ a b "Peter Sellers & Sophia Loren". Official UK Charts Archive. The Official UK Charts Company. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Mr. Topaze (1961)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 108.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 109.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 167.

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 98.

- ^ Walker 1981, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 91.

- ^ "'I Am Not a Funny Man'—Mr. Peter Sellers as Peter Sellers". The Times. London. 27 June 1962. p. 15.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Walker 1981, p. 118.

- ^ LoBrutto 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ^ LoBrutto 1999, p. 205.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 180.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 114.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 182.

- ^ Walker 1981, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 185.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 127.

- ^ a b Evans 1980, p. 101.

- ^ a b Walker 1981, p. 128.

- ^ "Peter Sellers triumphs as a detective". The Guardian. London. 27 January 1964. p. 7.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 187.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 191.

- ^ Gerber & Lisanti 2009, p. 133.

- ^ Lee Hill, "Interview with a Grand Guy": interview with Terry Southern

- ^ Kinn, Gail; Piazza, Jim. The Greatest Movies Ever, Black Dog Publishing (2008) p. 127

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 116.

- ^ Sellers 1981, p. 96.

- ^ Buchan, David (29 March 1977). "Sellers 'op'". Daily Express. London. p. 7.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 823.

- ^ a b Mortimer, John (27 July 1980). "Creative Force of a Meticulous Clown". The Sunday Times. London. p. 37.

- ^ Parkinson 2009, p. 255.

- ^ Parkinson 2009, p. 256.

- ^ "Obituary: Mr Peter Sellers". The Times. London. 25 July 1980. p. 16.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 352.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Danny (February 1981). "Giving Peter Sellers a Chance". Third Way. 4 (12). Hymns Ancient & Modern: 22–23. Cite error: The named reference "Smith" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 361.

- ^ a b Rich, Frank (14 January 1980). "Cinema: Gravity Defied (Subscription needed)". Time. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ a b c Dawson 2009, p. 211.

- ^ Walker 1981, p. 204.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 373.

- ^ "Seth Rogen To Grace Cover Of Playboy". Access Hollywood. NBCUniversal. 18 February 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Sikov 2002, pp. 381–382.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 379.

- ^ a b Graham, Caroline (8 February 2009). "The girl who got Peter Sellers' £5m - and she never even met him". Daily Mail. London. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ Sellers & Morecambe 2000.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Rigelsford 2004, p. 97.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 270.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (27 July 1980). "The delicate balance of Peter Sellers". The Sunday Times. London. p. 37.

- ^ Chorlton, Penny (25 July 1980). "Stars' tributes to Peter Sellers". The Guardian. London. p. 1.

- ^ a b Milne, Tom (27 July 1980). "The comic chameleon:". The Observer. London. p. 32.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 210.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 591.

- ^ Sikov 2002, p. 261.

- ^ Lewis 1995, p. 879.

- ^ Merwin, Ted (23 November 2010). "Who Was Peter Sellers?". The Jewish Week. New York. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ^ "Cook voted 'comedians' comedian'". BBC News. 2 January 2005. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ Saunders 2009, p. 22.

Bibliography

- Anthony, Barry (2010). The King's Jester. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-430-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carpenter, Humphrey (2003). Spike Milligan: The Biography. London: Coronet Books. ISBN 978-0-3408-2612-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dawson, Nick (2009). Being Hal Ashby: Life of a Hollywood Rebel. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2538-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Evans, Peter (1980). The Mask Behind the Mask. London: Severn House Publishers. ISBN 0-7278-0688-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ekland, Britt (1982). True Britt. New York: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-4250-5341-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gerber, Gail; Lisanti, Tom (2009). Trippin' With Terry Southern: What I Think I Remember. London: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-4114-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lewis, Roger (1995). The Life and Death of Peter Sellers. London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0-0997-4700-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - LoBrutto, Vincent (1999). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-3068-0906-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parkinson, Michael (2009). Parky: My Autobiography. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-3409-6167-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rigelsford, Adrian (2004). Peter Sellers: A Life in Character. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0270-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saunders, Robert A. (2009). The Many Faces of Sacha Baron Cohen: Politics, Parody, and the Battle Over Borat. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7391-2337-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sellers, Michael (1981). P.S. I Love You!. Glasgow: William Collins, Sons. ISBN 0-00-216649-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sellers, Michael; Morecambe, Gary (2000). Sellers on Sellers. London: André Deutsch. ISBN 978-0-2-339-9883-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sikov, Ed (2002). Mr Strangelove; A Biography of Peter Sellers. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-2830-7297-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Spizer, Bruce; Livingston, Alan W. (2000). The Beatles' Story on Capitol Records: Beatlemania & the Singles. London: Four Ninety-Eight Productions. ISBN 978-0-9662-6491-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tobler, Adrian (1992). NME Rock 'N' Roll Years. London: Reed International Books. ISBN 978-0-6005-7602-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker, Alexander (1981). Peter Sellers. Littlehampton: Littlehampton Book Services. ISBN 978-0-2977-7965-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Who Was Who (1971-1980). London: A & C Black. 1981. ISBN 978-0-7136-2176-1.

External links

- Official website

- Peter Sellers at IMDb

- Peter Sellers at the TCM Movie Database

- Peter Sellers at the BFI's Screenonline

- Use dmy dates from April 2012

- All articles with faulty authority control information

- 1925 births

- 1980 deaths

- BAFTA winners (people)

- Best British Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- English comedians

- English film actors

- English impressionists (entertainers)

- English Jews

- English radio actors

- English television actors

- Jewish actors

- Jewish comedians

- People from Southsea

- People from Portsmouth

- Royal Air Force airmen