Boko Haram: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 4 edits by Blaylockjam10 (talk) to last revision by 188.53.186.217. (TW) |

m Biased villification. |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

[[File:Islamist insurgency in Nigeria.svg|thumb|Nigerian territory under the control of Boko Haram as of 21 February 2015, shown in dark grey]] |

[[File:Islamist insurgency in Nigeria.svg|thumb|Nigerian territory under the control of Boko Haram as of 21 February 2015, shown in dark grey]] |

||

'''Boko Haram''' ("Western education is forbidden"), officially called '''Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'Awati Wal-Jihad''' ({{lang-ar|جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد}}, ''Jamā‘at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da‘wah wa’l-Jihād'', "Group of the [[Sunni Islam|People of Sunnah]] for Preaching and Jihad"), is an [[Islamist |

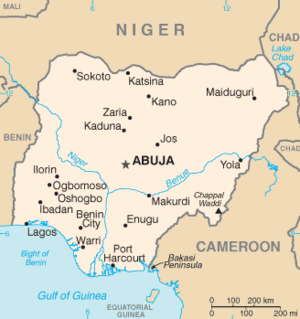

'''Boko Haram''' ("Western education is forbidden"), officially called '''Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'Awati Wal-Jihad''' ({{lang-ar|جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد}}, ''Jamā‘at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da‘wah wa’l-Jihād'', "Group of the [[Sunni Islam|People of Sunnah]] for Preaching and Jihad"), is an [[Islamist]] movement based in north-east [[Nigeria]], also active in [[Chad]], [[Niger]] and northern [[Cameroon]].<ref name=Bureau/> The group is led by [[Abubakar Shekau]]. Estimates of membership vary between a few hundred and 10,000. The group had been linked to [[al-Qaeda]] and in 2014 expressed support for the [[Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant]], pledging formal allegiance to it in 2015.<ref name="conflict-news.com"/><ref name="visionofhumanity.org-p53"/><ref name="telegraph.co.uk">{{cite news |url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/al-qaeda/10893889/Al-Qaeda-map-Isis-Boko-Haram-and-other-affiliates-strongholds-across-Africa-and-Asia.html |title=Al-Qaeda map: Isis, Boko Haram and other affiliates' strongholds across Africa and Asia |date=12 June 2014 |accessdate=1 September 2014}}, see interactive infographic</ref><ref name="visionofhumanity.org-p53" /><ref name="Boko">{{cite news |title=Boko Haram voices support for ISIS' Baghdadi|url=http://english.alarabiya.net/en/News/africa/2014/07/13/Boko-Haram-voices-support-for-ISIS-Baghdadi.html |publisher=Al Arabiya |date=13 July 2014 |accessdate=3 January 2014}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://twitter.com/azelin/status/574286226565566464/photo/1|title=EXCLUSIVE: Boko Haram pledges baya to the Islamic State|date=7 March 2015|accessdate=7 March 2015}}</ref> |

||

[[Boko Haram insurgency|Boko Haram killed more than 5,000 civilians between July 2009 and June 2014]], including at least 2,000 in the first half of 2014, in attacks occurring mainly in north-east, north-central and central Nigeria.<ref>{{cite news |date=19 July 2014 |url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/19/boko-haram-kill-100-people-take-control-nigerian-town |title=Boko Haram insurgents kill 100 people as they take control of Nigerian town |newspaper=The Guardian |date=2014-07-19 |accessdate=2014-07-20}}</ref><ref name="cfrNigeria Security Tracker">{{cite web | url=http://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-security-tracker/p29483 | title=Nigeria Security Tracker | publisher=Council of Foreign Relations | work=www.cfr.org | date=2014 | accessdate=21 July 2014 }}</ref><ref name=enc>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1581959/Boko-Haram |title=Boko Haram |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Britannica |accessdate=September 2014}}</ref> Corruption in the security services and human rights abuses committed by them have hampered efforts to counter the unrest.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/wp/2014/05/19/boko-haram-inside-the-state-department-debate-over-the-terrorist-label/ |title=Boko Haram: Inside the State Department debate over the 'terrorist' label |newspaper=The Washington Post |author=Glenn Kessler |date=19 May 2014 |accessdate=3 August 2014}}</ref><ref name="hrw report"/> Since 2009 Boko Haram have abducted more than 500 men,<ref>{{cite news |date=3 January 2015 |url=http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30666011 |title=Boko Haram unrest: Gunmen kidnap Nigeria villagers |publisher=BBC |date=2015-01-03 |accessdate=2015-01-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=15 August 2014 |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/15/boko-haram-kidnap-boys_n_5681165.html |title=Boko Haram Kidnap Dozens Of Boys In Northeast Nigeria: Witnesses |publisher=The Huffington Post |date=2014-07-15 |accessdate=2015-01-05}}</ref> women and children, including the [[Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping|kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls]] from [[Chibok]] in April 2014.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/27/nigeria-victims-abductions-tell-their-stories |title=Nigeria: Victims of Abductions Tell Their Stories |publisher=Human Rights Watch |date=27 October 2014 |accessdate=November 2014}}</ref> 650,000 people had fled the conflict zone by August 2014, an increase of 200,000 since May; by the end of the year 1.5 million had fled.<ref name="news 24">{{cite news |url=http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Islamists-force-650-000-Nigerians-from-homes-20140805 |title= |

[[Boko Haram insurgency|Boko Haram killed more than 5,000 civilians between July 2009 and June 2014]], including at least 2,000 in the first half of 2014, in attacks occurring mainly in north-east, north-central and central Nigeria.<ref>{{cite news |date=19 July 2014 |url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/19/boko-haram-kill-100-people-take-control-nigerian-town |title=Boko Haram insurgents kill 100 people as they take control of Nigerian town |newspaper=The Guardian |date=2014-07-19 |accessdate=2014-07-20}}</ref><ref name="cfrNigeria Security Tracker">{{cite web | url=http://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-security-tracker/p29483 | title=Nigeria Security Tracker | publisher=Council of Foreign Relations | work=www.cfr.org | date=2014 | accessdate=21 July 2014 }}</ref><ref name=enc>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/1581959/Boko-Haram |title=Boko Haram |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Britannica |accessdate=September 2014}}</ref> Corruption in the security services and human rights abuses committed by them have hampered efforts to counter the unrest.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/fact-checker/wp/2014/05/19/boko-haram-inside-the-state-department-debate-over-the-terrorist-label/ |title=Boko Haram: Inside the State Department debate over the 'terrorist' label |newspaper=The Washington Post |author=Glenn Kessler |date=19 May 2014 |accessdate=3 August 2014}}</ref><ref name="hrw report"/> Since 2009 Boko Haram have abducted more than 500 men,<ref>{{cite news |date=3 January 2015 |url=http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30666011 |title=Boko Haram unrest: Gunmen kidnap Nigeria villagers |publisher=BBC |date=2015-01-03 |accessdate=2015-01-05}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=15 August 2014 |url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/08/15/boko-haram-kidnap-boys_n_5681165.html |title=Boko Haram Kidnap Dozens Of Boys In Northeast Nigeria: Witnesses |publisher=The Huffington Post |date=2014-07-15 |accessdate=2015-01-05}}</ref> women and children, including the [[Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping|kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls]] from [[Chibok]] in April 2014.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/27/nigeria-victims-abductions-tell-their-stories |title=Nigeria: Victims of Abductions Tell Their Stories |publisher=Human Rights Watch |date=27 October 2014 |accessdate=November 2014}}</ref> 650,000 people had fled the conflict zone by August 2014, an increase of 200,000 since May; by the end of the year 1.5 million had fled.<ref name="news 24">{{cite news |url=http://www.news24.com/Africa/News/Islamists-force-650-000-Nigerians-from-homes-20140805 |title= |

||

Revision as of 22:42, 16 March 2015

| Boko Haram Group of the People of Sunnah for Preaching and Jihad (official name) | |

|---|---|

| جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد | |

| File:Logo of Boko Haram.svg | |

| Leaders | Mohammed Yusuf (founder) (KIA) Abubakar Shekau (current leader) |

| Dates of operation | 2002–present |

| Active regions | Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger, Chad |

| Ideology | Wahhabism Salafism Islamic fundamentalism |

| Part of | |

| Opponents | |

Boko Haram ("Western education is forbidden"), officially called Jama'atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda'Awati Wal-Jihad (Arabic: جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد, Jamā‘at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da‘wah wa’l-Jihād, "Group of the People of Sunnah for Preaching and Jihad"), is an Islamist movement based in north-east Nigeria, also active in Chad, Niger and northern Cameroon.[1] The group is led by Abubakar Shekau. Estimates of membership vary between a few hundred and 10,000. The group had been linked to al-Qaeda and in 2014 expressed support for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, pledging formal allegiance to it in 2015.[7][8][9][8][10][11]

Boko Haram killed more than 5,000 civilians between July 2009 and June 2014, including at least 2,000 in the first half of 2014, in attacks occurring mainly in north-east, north-central and central Nigeria.[12][13][14] Corruption in the security services and human rights abuses committed by them have hampered efforts to counter the unrest.[15][16] Since 2009 Boko Haram have abducted more than 500 men,[17][18] women and children, including the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls from Chibok in April 2014.[19] 650,000 people had fled the conflict zone by August 2014, an increase of 200,000 since May; by the end of the year 1.5 million had fled.[20][21]

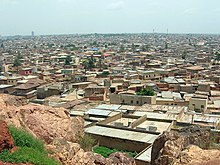

After its founding in 2002, Boko Haram's increasing radicalisation led to a violent uprising in July 2009 in which its leader was executed. Its unexpected resurgence, following a mass prison break in September 2010, was accompanied by increasingly sophisticated attacks, initially against soft targets, and progressing in 2011 to include suicide bombings of police buildings and the United Nations office in Abuja. The government's establishment of a state of emergency at the beginning of 2012, extended in the following year to cover the entire north-east of the country, resulted in a marked increase in both security force abuses and militant attacks. The Nigerian military proved ineffective in countering the insurgency, hampered by an entrenched culture of official corruption. Since mid-2014, the militants have been in control of swathes of territory in and around their home state of Borno, estimated at 50,000 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi) in January 2015, but have not captured the capital of Borno state, Maiduguri, where the group was originally based.[22]

Name

The official name is جماعة أهل السنة للدعوة والجهاد Jamā‘atu Ahli is-Sunnah lid-Da‘wati wal-Jihād, meaning "People Committed to the Prophet's Teachings for Propagation and Jihad".[23] The group was also originally known informally as 'Yusifiyya', after its first leader, Mohammed Yusuf.[24]

The name "Boko Haram" is usually translated as "Western education is forbidden". Haram is from the Arabic حَرَام ḥarām, "forbidden"; and the Hausa word Template:Wiktha [the first vowel is long, the second pronounced in a low tone], originally meaning "fake", has come to mean[25] and is widely translated as "Western education" and thought to be a possible corruption of the English word "book".[26][27] Boko Haram has also been translated as "Western influence is a sin"[28] and "Westernization is sacrilege".[14]

Some Nigerians dismiss Western education as ilimin boko ("education fake") and draw a distinction between makaranta alkorani (religious school), based on the Qur'an where students learn to write and recite Arabic, and makaranta boko — government schools imparting secular education in the colonial English (official) language.[29] [26][27][30]

Ideology

Boko Haram was founded as a Sunni Islamic fundamentalist sect advocating a strict form of sharia law and developed into a Salafist-jihadi group in 2009, influenced by the Wahhabi movement. The movement is so diffuse that fighters associated with it do not necessarily follow Salafi doctrine.[31][32][33][34][35][36] Boko Haram seeks the establishment of an Islamic state in Nigeria. It opposes the Westernization of Nigerian society and the concentration of the wealth of the country among members of a small political elite, mainly in the Christian south of the country.[37][38] Nigeria is Africa's biggest economy, but 60% of its population of 173 million (2013) live on less than $1 a day.[39][40][41] The sharia law imposed by local authorities, beginning with Zamfara in January 2000 and covering 12 northern states by late 2002, may have promoted links between Boko Haram and political leaders, but was considered by the group to have been corrupted.[42]: 101 [43][44][45]

According to Borno Sufi Imam Sheik Fatahi, Yusuf was trained by Kano Salafi Izala Sheik Ja'afar Mahmud Adamu, who called him the "leader of young people"; the two split some time in 2002–4. They both preached in Maiduguri's Indimi Mosque, which was attended by the deputy governor of Borno.[24][46] Many of the group were reportedly inspired by Mohammed Marwa, known as Maitatsine ("He who curses others"), a self-proclaimed prophet (annabi, a Hausa word usually used only to describe the founder of Islam) born in Northern Cameroon who condemned the reading of books other than the Quran.[26][47][48][49] In a 2009 BBC interview, Yusuf, described by analysts as being well-educated, reaffirmed his opposition to Western education. He rejected the theory of evolution, said that rain is not "an evaporation caused by the sun", and that the Earth is not a sphere.[50]

Symbols

Boko Haram uses a number of visual symbols in flags, printed materials and in propaganda videos that are regularly released to the public. The main logo is composed of three elements, which may also appear separately:

- Two crossed Kalashnikov AK-47 automatic rifles. This symbolizes armed struggle and the willingness to use violence.

- An open Quran, the holy book of Islam. This symbolizes Islamic proselytizing.

- The Islamic declaration of faith, the Shahada. The declaration is written in Arabic. It reads "There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah."

In addition to these symbols, in concert with their proclamation of support for the Syria-/Iraq-based group, Boko Haram has recently also used the Black Standard variant flag used by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

History

Background

Before colonisation and subsequent annexation into the British Empire in 1900 as Colonial Nigeria, the Bornu Empire ruled the territory where Boko Haram is currently active. It was a sovereign sultanate run according to the principles of the Constitution of Medina, with a majority Kanuri Muslim population. In 1903, both the Bornu Sultanate and Sokoto Caliphate came under the control of the British, who used educational institutions to help spread Christianity in the region.[52] British occupation ended with Nigerian independence in 1960.[53][54][55]

Except for a brief period of civilian rule between 1979 and 1983, Nigeria was governed by a series of military dictatorships from 1966 until the advent of democracy in 1999. Ethnic militancy is thought to have been one of the causes of the 1967–70 civil war; religious violence reached a new height in 1980 in Kano, the largest city in the north of the country, where the Muslim fundamentalist sect Yan Tatsine ("followers of Maitatsine") instigated riots that resulted in four or five thousand deaths. In the ensuing military crackdown, Maitatsine was killed, fuelling a backlash of increased violence that spread across other northern cities over the next twenty years.[56] Social inequality, poverty and the increasingly radical nature of Islam, locally and internationally, contributed both to the Maitatsine and Boko Haram uprisings.[42]: 97–98

In the decades since the end of British occupation, politicians and academics from the mainly Islamic North have expressed their fundamental opposition to Western education. Political ethno-religious interest groups, whose membership includes influential political, military and religious leaders, have thrived in Nigeria, though they were largely suppressed under military rule. Their paramilitary wings, formed since the country's return to civilian rule, have been implicated in much of the sectarian violence in the years following.[57]

Boko Haram founding and early years

Mohammed Yusuf founded the sect that became known as Boko Haram in 2002 in Maiduguri, the capital of the north-eastern state of Borno. He established a religious complex and school that attracted poor Muslim families from across Nigeria and neighbouring countries. The center had the political goal of creating an Islamic state, and became a recruiting ground for jihadis. By denouncing the police and state corruption, Yusuf attracted followers from unemployed youths.[32][53][58][59] He is reported to have used the existing infrastructure in Borno of the Izala Society (Jama'at Izalatil Bidiawa Iqamatus Sunnah), a popular conservative Islamic sect, to recruit members, before breaking away to form his own faction. The Izala were originally welcomed into government, along with people sympathetic to Yusuf. Boko Haram conducted its operations more or less peacefully during the first seven years of its existence, withdrawing from society into remote north-eastern areas. The government repeatedly ignored warnings about the increasingly militant character of the organization.[33][60] The Council of Ulama advised the government and the Nigerian Television Authority not to broadcast Yusuf's preaching, but their warnings were ignored. Yusuf's arrest elevated him to hero status. Borno's Deputy Governor Alhaji Dibal has claimed that the al-Qaeda had ties with Boko Haram, but broke them when they decided that Yusuf was an unreliable person.[24]

Campaign of violence

2009

In 2009 police began an investigation into the group code-named 'Operation Flush'. On 26 July, security forces arrested nine Boko Haram members and confiscated weapons and bomb-making equipment. Either this or a clash with police during a funeral procession led to revenge attacks on police and widespread rioting. A joint military task force operation was launched in response, and by 30 July more than 700 people had been killed, mostly Boko Haram members, and police stations, prisons, government offices, schools and churches had been destroyed.[14][42]: 98–102 [61][62] Yusuf was arrested, and died in custody "while trying to escape". As had been the case decades earlier in the wake of the 1980 Kano riots, the killing of the leader of an extremist group would have unintended consequences. He was succeeded by Abubakar Shekau, formerly his second-in-command.[63][64] A classified cable sent from the U.S. Embassy in Abuja in November 2009, available on WikiLeaks, is illuminating:[24]

[Borno political and religious leaders] ... asserted that the state and federal government responded appropriately and, apart from the opposition party, overwhelmingly supported Yusuf's death without misgivings over the extrajudicial killing. Security remained a concern in Borno, with residents expressing concern about importation of arms and exchanges of religious messages across porous international borders.

There were reports that Yusuf's deputy had survived, and audio tapes were believed to be in circulation in which Boko Haram threatened future attacks. However, many observers did not anticipate imminent bloodshed. Security in Borno was downgraded. Borno government official Alhaji Boguma believed that the state deserved praise from the international community for ending the conflict in such a short time, and that the "wave of fundamentalism" had been "crushed".[24]

2010

In September 2010, having regrouped under their new leader, Boko Haram broke 105 of its members out of prison in Maiduguri along with over 600 other prisoners and went on to launch attacks in several areas of northern Nigeria.[56][65][66]

2011

Under Shekau's leadership, the group continuously improved its operational capabilities. After launching a string of IED attacks against soft targets, and its first vehicle-borne IED attack in June 2011, killing 6 at the Abuja police headquarters, in August Boko Haram bombed the UN headquarters in Abuja, the first time they had struck a Western target. A spokesman claiming responsibility for the attack, in which 11 UN staff members died as well as 12 others, with more than 100 injured, warned of future planned attacks on U.S. and Nigerian government interests. Speaking soon after the U.S. embassy's announcement of the arrival in the country of the FBI, he went on to announce Boko Haram's terms for negotiation: the release of all imprisoned members. The increased sophistication of the group led observers to speculate that Boko Haram was affiliated with AQIM, which was active in Niger.[65][66][67][68][69][70]

Boko Haram has maintained a steady rate of attacks since 2011, striking a wide range of targets, multiple times per week. They have attacked politicians, religious leaders, security forces and civilian targets. The tactic of suicide bombing, used in the two attacks in the capital on the police and UN headquarters, was new to Nigeria. In Africa as a whole, it had only been used by al-Shabaab in Somalia and, to a lesser extent, AQIM.[1][14][68][71][72][73]

Bombings following 2011 presidential inauguration

Within hours of Goodluck Jonathan's presidential inauguration in May 2011, Boko Haram carried out a series of bombings in Bauchi, Zaria and Abuja. The most successful of these was the attack on the army barracks in Bauchi. A spokesman for the group told BBC Hausa that the attack had been carried out, as a test of loyalty, by serving members of the military hoping to join the group. This charge was later refuted by an army spokesman, who claimed, "This is not a banana republic." However, on 8 January 2012, the president would announce that Boko Haram had in reality infiltrated both the army and the police, as well as the executive, parliamentary and legislative branches of government. Boko Haram's spokesman also claimed responsibility for the killing outside his home in Maiduguri of the politician Abba Anas Ibn Umar Garbai, the younger brother of the Shehu of Borno, who was the second most prominent Muslim in the country after the Sultan of Sokoto. He added, "We are doing what we are doing to fight injustice, if they stop their satanic ways of doing things and the injustices, we would stop what we are doing."[74][75]

This was one of several political and religious assassinations Boko Haram carried out that year, with the presumed intention of correcting injustices in the group's home state of Borno. Meanwhile, the trail of massacres continued relentlessly, apparently leading the country towards civil war. By the end of 2011, these conflicting strategies led observers to question the group's cohesion; comparisons were drawn with the diverse motivations of the militant factions of the oil-rich Niger Delta. Adding to the confusion, in November, the State Security Service announced that four criminal syndicates were operating under the name 'Boko Haram'.[71][76][77][78]

The common theme throughout the north-east was the targeting of police, who were regularly massacred at work or in drive-by shootings at their homes, either in revenge for the killing of Yusuf, or as representatives of the state apparatus, or for no particular reason. Five officers were arrested for Yusuf's murder, which had no noticeable effect on the level of unrest. Opportunities for criminal enterprise flourished. Hundreds of police were dead and more than 60 police stations had been attacked by mid-2012. The government's response to this self-reinforcing trend towards insecurity was to invest heavily in security equipment, spending $5.5 billion, 20% of their overall budget, on bomb detection units, communications and transport; and $470 million on a Chinese CCTV system for Abuja, which has failed in its purpose of detecting or deterring acts of terror.[77][79][80][81][82][83]

The election defeat of former military dictator Muhammadu Buhari increased religious political tension, as the presidency was expected to change hands to a northern, Muslim candidate. Sectarian riots engulfed the twelve northern states of the country during the three days following the election, leaving more than 800 dead and 65,000 displaced. The subsequent campaign of violence by Boko Haram culminated in a string of bombings across the country on Christmas Day. In the outskirts of Abuja, 37 died in a church that had its roof blown off. "Cars were in flames and bodies littered everywhere," one resident commented, words repeated in nearly all press reports about the aftermath of the bombings. Similar Christmas events had occurred in previous years. Jonathan declared a state of emergency on New Year's Eve in local government areas of Jos, Borno, Yobe and Niger, and closed the international border in the north-east.[84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92]

2012

State of emergency

Boko Haram carried out 115 attacks in 2011, killing 550. The state of emergency would usher in an intensification of violence. The opening three weeks of 2012 accounted for more than half of the death total of the preceding year. Two days after the state of emergency was declared, Boko Haram released an ultimatum to southern Nigerians living in the north, giving them three days to leave. Three days later they began a series of mostly small-scale attacks on Christians and members of the Igbo ethnic group, causing hundreds to flee. In Kano, on 20 January, they carried out by far their most deadly action yet, an assault on police buildings, killing 190. One of the victims was a TV reporter. The attacks included a combined use of car bombs, suicide bombers and IEDs, supported by uniformed gunmen.[31][93][94][95][96][97][98]

Denouncements of violence and human rights abuses

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published reports in 2012 that were widely quoted by government agencies and the media, based on research conducted over the course of the conflict in the worst affected areas of the country. The NGOs were critical of both security forces and Boko Haram. HRW stated "Boko Haram should immediately cease all attacks, and threats of attacks, that cause loss of life, injury, and destruction of property. The Nigerian government should take urgent measures to address the human rights abuses that have helped fuel the violent militancy." According to the 2012 U.S. Department of State Country Report on Human Rights Practices,[16]

... serious human rights problems included extrajudicial killings by security forces, including summary executions; security force torture, rape, and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of prisoners, detainees, and criminal suspects; harsh and life-threatening prison and detention center conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention; prolonged pretrial detention; denial of fair public trial; executive influence on the judiciary; infringements on citizens' privacy rights; restrictions on freedom of speech, press, assembly, religion, and movement ...

On 9 October witnesses in Maiduguri claimed members of the JTF [Joint Task Force] "Restore Order", [a vigilante group] based in Maiduguri, went on a killing spree after a suspected Boko Haram bomb killed an officer. Media reported the JTF killed 20 to 45 civilians and razed 50 to 100 houses in the neighborhood. The JTF commander in Maiduguri denied the allegations. On 2 November, witnesses claimed the JTF shot and killed up to 40 people during raids in Maiduguri. The army claimed it dismissed some officers from the military as a result of alleged abuses committed in Maiduguri, but there were no known formal prosecutions in Maiduguri by year's end.

Credible reports also indicated ... uniformed military personnel and paramilitary mobile police carried out summary executions, assaults, torture, and other abuses throughout Bauchi, Borno, Kano, Kaduna, Plateau, and Yobe states ... The national police, army, and other security forces committed extrajudicial killings and used lethal and excessive force to apprehend criminals and suspects, as well as to disperse protesters. Authorities generally did not hold police accountable for the use of excessive or deadly force or for the deaths of persons in custody. Security forces generally operated with impunity in the illegal apprehension, detention, and sometimes extrajudicial execution of criminal suspects. The reports of state or federal panels of inquiry investigating suspicious deaths remained unpublished.

There were no new developments in the case of five police officers accused of executing Muhammad Yusuf in 2009 at a state police headquarters. In July 2011 authorities arraigned five police officers in the federal high court in Abuja for the murder of Yusuf. The court granted bail to four of the officers, while one remained in custody.

Police use of excessive force, including use of live ammunition, to disperse demonstrators resulted in numerous killings during the year. For example, although the January fuel subsidy demonstrations generally remained peaceful, security forces reportedly fired on protesters in various states across the country during those demonstrations, resulting in 10 to 15 deaths and an unknown number of wounded.

Despite some improvements resulting from the closure of police checkpoints in many parts of the country, states with an increased security presence due to the activities of Boko Haram experienced a rise in violence and lethal force at police and military roadblocks.

Continuing abductions of civilians by criminal groups occurred in the Niger Delta and Southeast ... Police and other security forces were often implicated in the kidnapping schemes.

Although the constitution and law prohibit such practices and provide for punishment of such abuses, torture is not criminalized, and security service personnel, including police, military, and State Security Service (SSS) officers, regularly tortured, beat, and abused demonstrators, criminal suspects, detainees, and convicted prisoners. Police mistreated civilians to extort money. The law prohibits the introduction into trials of evidence and confessions obtained through torture; however, police often used torture to extract confessions.[99]

2013

Nigeria's Borno State, where Boko Haram is based, adjoins Lake Chad, as do Niger, Cameroon and the country of Chad. The conflict, and refugees, spilled over the national borders to involve all four countries.

Since early 2013, Boko Haram have increasingly operated in Northern Cameroon, and have been involved in skirmishes along the borders of Chad and Niger. They have been linked to a number of kidnappings, often reportedly in association with the splinter group Ansaru, drawing them a higher level of international attention.

The U.S. Bureau of Counterterrorism provides the following summary of Boko Haram's 2013 foreign operations:

In February 2013, Boko Haram was responsible for kidnapping seven French tourists in the far north of Cameroon. In November 2013, Boko Haram members kidnapped a French priest in Cameroon. In December 2013, Boko Haram gunmen reportedly attacked civilians in several areas of northern Cameroon. Security forces from Chad and Niger also reportedly partook in skirmishes against suspected Boko Haram members along Nigeria's borders. In 2013, the group also kidnapped eight French citizens in northern Cameroon and obtained ransom payments for their release.[1]

Boko Haram has often managed to evade the Nigerian army by retreating into the hills around the border with Cameroon, whose army is apparently unwilling to confront them. Nigeria, Chad and Niger had formed a Multinational Joint Task Force in 1998. In February 2012, Cameroon signed an agreement with Nigeria to establish a Joint Trans-Border Security Committee, which was inaugurated in November 2013, when Cameroon announced plans to conduct "coordinated but separate" border patrols in 2014. It convened again in July 2014 to further improve cooperation between the two countries.[100][101][102][103][104]

In late 2013 Amnesty International received 'credible' information that over 950 inmates had died in custody, mostly in detention centres in Maiduguri and Damaturu, within the first half of the year. Official state corruption was also documented in December 2013 by the UK Home Office:[105][106]

The NPF [Nigeria Police Force], SSS, and military report to civilian authorities; however, these security services periodically act outside of civilian control. The government lack effective mechanisms to investigate and punish abuse and corruption. The NPF remain susceptible to corruption, commit human rights abuses, and generally operate with impunity in the apprehension, illegal detention, and sometimes execution of criminal suspects. The SSS also commit human rights abuses, particularly in restricting freedom of speech and press. In some cases private citizens or the government brought charges against perpetrators of human rights abuses in these units. However, most cases lingered in court or went unresolved after an initial investigation.

The state of emergency was extended in May 2013 to cover the whole of the three north-eastern states of Borno, Adamawa and Yobe, raising tensions in the region. In the 12 months following the announcement, 250,000 fled the three states, followed by a further 180,000 between May and August 2014. A further 210,000 fled from bordering states, bringing the total displaced by the conflict to 650,000. Many thousands left the country. An August 2014 AI video showed army and allied militia executing people, including by slitting their throats, and dumping their bodies in mass graves.[107][108][109]

2014

Kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in April 2014

In April 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls from Chibok, Borno. More than 50 of them soon escaped, but the remainder have not been released. Instead, Shekau, who has a reward of $7 million offered by the United States Department of State since June 2013 for information leading to his capture, announced his intention of selling them into slavery. The incident brought Boko Haram extended global media attention, much of it focused on the pronouncements of the First Lady of the United States. Faced with outspoken condemnation for his perceived incompetence, and detailed accusations from Amnesty International of state collusion, President Jonathan responded by hiring a Washington PR firm.[112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119]

Parents of the missing schoolgirls and those who had escaped were kept waiting until July to meet with the president, which caused them concern. In October, the government announced the girls' imminent release, but the information proved unreliable. The announcement to the media of a peace agreement and the imminent release of all the missing girls was followed days later by a video message in which Shekau stated that no such meeting had taken place and that the girls had been "married off". The announcement to the media, unaccompanied by any evidence of the reality of the agreement, was thought by analysts to have been a political ploy by the president to raise his popularity before his confirmation of his candidacy in the 2015 general election. Earlier in the year, the girls' plight had featured on "#BringBackOurGirls" political campaign posters in the streets of the capital, which the president denied knowledge of and soon took down after news of criticism surfaced. These posters, which were interpreted, to the dismay of campaigners for the girls' recapture, as being designed to benefit from the fame of the kidnapping, had also been part of Jonathan's "pre-presidential campaign". In September, "#BringBackGoodluck2015" campaign posters again drew criticism.[120] The official announcement of the president's candidacy was made before cheering crowds in Abuja on 11 November.[121]

Kidnapping of the Cameroon vice-president's wife

In 2014 Boko Haram continued to increase its presence in northern Cameroon. On 16 May, ten Chinese workers were abducted in a raid on a construction company camp in Waza, near the Nigerian border. Vehicles and explosives were also taken in the raid, and one Cameroon soldier was killed. Cameroon's antiterrorist Rapid Intervention Battalion attempted to intervene but were vastly outnumbered.[122] In July, the vice-president's home village was attacked by around 200 militants; his wife was kidnapped, along with the Sultan of Kolofata and his family. At least 15 people, including soldiers and police, were killed in the raid. The vice-president's wife was subsequently released in October, along with 26 others including the ten Chinese construction workers who had been captured in May; authorities made no comment about any ransom, which the Cameroon government had previously claimed it never pays.[123] In a separate attack, nine bus passengers and a soldier were shot dead and the son of a local chief was kidnapped. Hundreds of local youths are suspected to have been recruited. In August, the remote Nigerian border town of Gwoza was overrun and held by the group. In response to the increased militant activity, the Cameroonian president sacked two senior military officers and sent his army chief with 1000 reinforcements to the northern border region.[124][125][126]

Between May and July 2014, 8,000 Nigerian refugees arrived in the country, up to 25% suffering from acute malnutrition. Cameroon, which ranked 150 out of 186 on the 2012 UNDP HDI, hosted, as of August 2014, 107,000 refugees fleeing unrest in the CAR, a number that was expected to increase to 180,000 by the end of the year.[127][128][129] A further 11,000 Nigerian refugees crossed the border into Cameroon and Chad during August.[130]

Announcing an Islamic caliphate

The attack on Gwoza signalled a change in strategy for Boko Haram, as the group continued to capture territory in north-eastern and eastern areas of Borno, as well as in Adamawa and Yobe. Attacks across the border were repelled by the Cameroon military.[131] The territorial gains were officially denied by the Nigerian military. In a video obtained by the news agency AFP on 24 August, Shekau announced that Gwoza was now part of an Islamic caliphate.[132] The town of Bama, 70 kilometres (45 mi) from the state capital Maiduguri, was reported to have been captured at the beginning of September, resulting in thousands of residents fleeing to Maiduguri, even as residents there were themselves attempting to flee.[133] The military continued to deny Boko Haram's territorial gains, which were, however, confirmed by local vigilantes who had managed to escape. The militants were reportedly killing men and teenage boys in the town of over 250,000 inhabitants. Soldiers refused orders to advance on the occupied town; hundreds fled across the border into Cameroon, but were promptly repatriated. Fifty-four deserters were later sentenced to death by firing squad.[134][135]

On 17 October, the Chief of the Defence Staff announced that a ceasefire had been brokered, stating "I have accordingly directed the service chiefs to ensure immediate compliance with this development in the field." Despite a lack of confirmation from the militants, the announcement was publicised in newspaper headlines around the world. Within 48 hours, however, the same publications were reporting that Boko Haram attacks had nevertheless continued unabated. It was reported that factionalisation would make such a deal particularly difficult to achieve.[136][137][138]

On 29 October Mubi, a town of 200,000 in Adamawa, fell to the militants, further undermining confidence in the peace talks. Thousands fled south to Adamawa's capital city, Yola.[139] Amid media speculation that the ceasefire announcement had been part of President Jonathan's re-election campaign, a video statement released by Boko Haram through the normal communication channels via AFP on 31 October stated that no negotiations had in fact taken place.[140][141] Mubi was said to have been recaptured by the army on 13 November. On the same day, Boko Haram seized Chibok; two days later, the army recaptured the largely deserted town. As of 16 November it was estimated that more than twenty towns and villages had been taken control of by the militants.[142][143] On 28 November, 120 died in an attack at the central mosque in Kano during Friday prayers. There were 27 Boko Haram attacks during the month of November, killing at least 786.[144][145]

On 3 December, it was reported that several towns in North Adamawa had been recovered by the Nigerian military with the help of local vigilantes. Bala Nggilari, the governor of Adamawa state, said that the military were aiming to recruit 4,000 vigilantes.[146] On 13 December Boko Haram attacked the village of Gumsuri in Borno, killing over 30, and kidnapping over 100 women and children.[147]

Attacks in Cameroon

In the second half of December, the focus of activity switched to the Far North Region of Cameroon, beginning on the morning of 17 December when an army convoy was attacked with an IED and ambushed by hundreds of militants near the border town of Amchide, 60 kilometres (40 mi) north of the state capital Maroua. One soldier was confirmed dead, and an estimated 116 militants were killed in the attack, which was followed by another attack overnight with unknown casualties.[148] On 22 December the Rapid Intervention Battalion followed up with an attack on a Boko Haram training camp near Guirdivig, arresting 45 militants and seizing 84 children aged 7–15 who were undergoing training, according to a statement from Cameroon's Ministry of Defense. The militants fled in pick-up trucks carrying an unknown number of their dead; no information on army casualties was released.[149] On 27–28 December five villages were simultaneously attacked, and for the first time the Cameroon military launched air attacks when Boko Haram briefly occupied an army camp. Casualty figures were not released. According to Information Minister Issa Tchiroma, "Units of the group attacked Makari, Amchide, Limani and Achigachia in a change of strategy which consists of distracting Cameroonian troops on different fronts, making them more vulnerable in the face of the mobility and unpredictability of their attacks."[150]

2015

Baga massacre

On 3 January 2015, Boko Haram again attacked Baga, seizing it and the military base used by a multinational force set up to fight them. The town was burned and the people massacred. Although the death toll of the massacre was earlier estimated by local officials to be upwards of 2000,[151] the Defence Ministry has now dismissed these claims as "speculation and conjecture" and "exaggerated". They estimate the death toll to be closer to 150 instead. It should be noted, however, that this is an estimation and that Nigeria has often been accused of underestimating casualty figures in an effort to downplay the threat of Boko Haram.[152] Some residents escaped to nearby Chad.[153]

Cameroon raids

On 12 January Boko Haram attacked a Cameroon military base in Kolofata. Government forces report killing 143 militants, while one Cameroon soldier was killed.[154] On 18 January Boko Haram raided two Tourou Cameroon area villages, torching houses, killing some residents and kidnapping between 60 and 80 people including an estimated 50 young children between the ages of 10 and 15.[155]

Chad attacks

On 4 February the Chad Army killed over 200 Boko Haram militants, as a response to an offensive the day before.[156] Soon afterwards, Boko Haram launched an attack on the Cameroonian town of Fotokol, killing 81 civilians, 13 Chadian and 6 Cameroonian soldiers.[157]

Allegiance to Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant

On 7 March 2015, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau pledged allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant via an audio message posted on the organisation's Twitter account.[158][159] On 12 March 2015, ISIL's spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani released an audiotape in which he welcomed the pledge of allegiance and described it as an expansion of the group's caliphate to West Africa.[160]

Organization

Leaders, structure and members

Although Boko Haram is organized in a hierarchical structure with one overall leader, the group also operates as a clandestine cell system using a network structure.[161] The boundaries of the organization are sometimes not clear. In many cases leadership is direct while in others it is more 'inspirational'. Boko Haram operates as an insurgency/guerilla force, with units having between 300 and 500 fighters each.[162] Estimates of the total number of fighters range between 500 and 9,000.[8][7][163] Fighters are mainly drawn from the Kanuri ethnic group.[164]

Between 2002 and 2009, Boko Haram was led by the organization founder, Islamist cleric Mohammed Yusuf. In 2009, after Yusuf was killed, leadership passed to Abubakar Shekau, who was Yusuf's second-in command. Shekau has since married one of Mohammed Yusuf's four wives. Abubakar Shekau was born in Yobe, Nigeria between 1965 and 1975 and is of Kanuri ethnicity.[165] He speaks Arabic, Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri. In addition to operational leadership, Shekau is also the religious leader of Boko Haram and regularly delivers sermons to his followers. In 2012, the U.S. Department of State designated Abubakar Shekau a Specially Designated Global Terrorist under Executive Order 13224. Under Shekau's leadership, Boko Haram's operational capabilities have grown.[165]

Momodu Bama had been named as second in command after Abubakar Shekau took over as leader. Bama was killed in 2013. Another regional leader that was killed was known as Abba. Aminu Sadiq Ogwuche is suspected of organizing the April 2014 Abuja bombing and is wanted in connection with the 2014 girl kidnappings.[citation needed]

Financing

Kidnappings, robbery and extortion

Boko Haram gets funding from bank robberies and kidnapping ransoms.[94][166] As an example, in the spring of 2013 gunmen from Boko Haram kidnapped a family of seven French tourists on vacation in Cameroon. Two months later, the kidnappers released the hostages along with 16 others in exchange for a ransom of $3.15 million.[167]

Any funding they may have received in the past from al-Qaeda affiliates is insignificant compared to the estimated $1 million ransom for each wealthy Nigerian or foreigner kidnapped. Cash is moved around by couriers, making it impossible to track, and communication is conducted face-to-face. Their mode of operation, which is thought to include paying local youths to track army movements, is such that little funding is required to carry out attacks.[168] Equipment captured from fleeing soldiers keeps the group constantly well-supplied.[169] The group also extorts local governments. A spokesman of Boko Haram claimed that Kano state governor Ibrahim Shekarau and Bauchi state governor Isa Yuguda had paid them monthly.[170][171]

Donations from Islamist sympathizers

After Boko Haram was founded, it received most of its funds from local donors who supported its goal of imposing Islamic law while ridding Nigeria of Western influences. In more recent times, Boko Haram has broadened its funding by drawing on foreign donors, and other ventures such as fake charity organizations.[167] In February 2012, recently arrested officials revealed that while the organization initially relied on donations from members, its links with Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb opened it up to funding from groups in Saudi Arabia and the UK.[172][173]

Boko Haram cloaks its sources of finance through the use of a highly decentralized distribution network. The group employs an Islamic model of money transfer called hawala, which is based on an honor system and a global network of agents that makes the financing difficult to track.[167] In the past, Nigerian officials have been criticized for being unable to trace much of the funding that Boko Haram has received.[174]

Drug trafficking, smuggling and poaching

Boko Haram has occasionally been connected in media reports with cocaine trafficking;[175][176] according to some there appears to be a lack of evidence regarding this means of funding. James Cockayne, formerly Co-Director of the Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation and Senior Fellow at the International Peace Institute, wrote in 2012,[177][178]

Given their appreciation of the contested nature of much African governance, it comes as something of a surprise that Carrier and Klantschnig [Review of Africa and the War on Drugs, 2012] fiercely downplay the impact that cocaine trafficking is having on West African governance. On the basis of just three case studies (Guinea-Bissau, Lesotho[clarification needed] and Nigeria) the authors conclude that 'state complicity' in the African drug trade is 'rare', and the dominant paradigm is 'repression'. As a result, they radically understate the close involvement of political and military actors in drug trafficking – particularly in West African cocaine trafficking – and overlook the growing power of drug money in African electoral politics, local and traditional governance, and security.

According to Loretta Napoleoni, an expert on terrorist finance, Boko Haram funds itself by trafficking drugs from drug cartels in Latin America. "Nobody wants to admit that cocaine reaches Europe via West Africa," says Napoleoni, "This kind of business is a type of business where Islamic terrorist organizations are very much involved."[167]

Boko Haram also engages in other forms of smuggling. According to a report from the Animal Protection Institute, the group has joined other criminal groups in Africa in the billion-dollar rhino and elephant poaching industry.[167]

Ties to other designated terrorist groups

This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (February 2015) |

Evidence going back to 2002 or earlier ties Boko Haram to al-Qaeda and its regional affiliates. According to E. J. Hogendoorn, author of a report on Boko Haram for the International Crisis Group, Osama bin Laden himself sent $3 million in seed money to Nigeria to fund the spreading of his ideologies, and some of this money was used to help start the Boko Haram group. This information came from a Nigerian researcher's interview with a member of Boko Haram "who was very knowledgeable about the origins of the group". It also appears that bin Laden provided strategic direction to the Nigerians. In 2011, correspondence between bin Laden and Boko Haram was found in bin Laden's compound after the raid that killed him.[179]

In July 2009 AQIM issued a statement of support for Boko Haram and when the Nigerian government attacked the group, its members scattered to various al-Qaida operations.[180]

In July 2010, Boko Haram's leader Abubakar Shekau praised al-Qaeda and offered his condolences for the "martyrdom" of al-Qaeda's two top Iraq leaders. "Do not think jihad is over," Shekau said. "Rather, jihad has just begun. O America, die with your fury." In November 2012, Shekau "expressed Boko Haram's solidarity with al-Qaeda affiliates in Afghanistan, Iraq, North Africa, Somalia and Yemen".[181]

In June 2012 the U.S. State Department designated Khalid al-Barnawi and Abubakar Adam Kambar as terrorists that "have ties to Boko Haram and have close links to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb", at the same time as it designated Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau as a terrorist. In June 2013, when the "Rewards for Justice" program offered a $7 million reward for information leading to the capture of Shekau, similar rewards were offered for leaders in AQIM and its offshoots. Shekau is charged with "expressing solidarity with al-Qaeda and threatening the United States" and that "there are reported communications, training, and weapons links between Boko Haram, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which may strengthen Boko Haram's capacity to conduct terrorist attacks." These three organizations are all formal branches of al-Qaeda.

Speaking by phone to reporters in in November 2012, group spokesman Abu Qaqa said: "We are together with al-Qaeda, they are promoting the cause of Islam, just as we are doing. Therefore they help us in our struggle and we help them, too." The 2012 Reuters special report details how fighters have trained with al-Qaeda affiliates in small groups over at least 6 years.[182]

According to the UN Security Council listing of Boko Haram under the al-Qaeda sanctions regime in May 2014,[183] the group "has maintained a relationship with AQIM for training and material support purposes", and "gained valuable knowledge on the construction of improvised explosive devices from AQIM". The UN found that a "number of Boko Haram members fought alongside al Qaeda affiliated groups in Mali in 2012 and 2013 before returning to Nigeria with terrorist expertise". AQIM is one of al-Qaeda's regional branches, whose leader, Abu Musab Abdel Wadoud, has sworn an oath of allegiance to al-Qaeda's senior leadership.[181]

However, al-Qaeda Core has never officially accepted Boko Haram as an affiliate, and after the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping al-Qaeda did not praise Boko Haram, leading some analysts to conclude that the group was too violent for al-Qaeda.[180][184] The form and structure of al-Qaeda and its affiliates remains a matter of debate within the US Intelligence Community, and the exact current status of ties between Boko Haram and the al-Qaeda organization remains unclear.[179]

In July 2014 Shekau released a 16-minute video where he voiced support for ISIL's head Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, al-Qaeda's head Ayman al-Zawahiri and Afghan Taliban leader Mullah Omar.[185] In March 2015 Shekau formally pledged allegiance to ISIL, which was accepted by the group's spokesman several days later.[160]

Response by Nigerian authorities

The Nigerian military is, in the words of a former British military attaché speaking in 2014, "a shadow of what it's reputed to have once been. It's fallen apart." They are short of basic equipment, including radios and armoured vehicles. Morale is said to be low. Senior officers are alleged to be skimming military procurement budget funds that are intended to pay for the standard issue equipment of soldiers. The country's defense budget accounts for more than a third of the security budget of $5.8 billion, but only 10% is allocated to capital spending.[186] In a 2014 United States Department of Defense assessment, funds are being "skimmed off the top", troops are "showing signs of real fear", and are "afraid to even engage".[31]: 9

In the summer of 2013, the Nigerian military shut down mobile phone coverage in the three north-eastern states to disrupt the group's communication and ability to detonate IEDs. Accounts from military insiders and data of Boko Haram incidences before, during and after the mobile phone blackout suggest that the shut down was ‘successful’ from a military- tactical point of view. However it angered citizens in the region (owing to negative social and economic consequences of the mobile shutdown) and engendered negative opinions toward the state and new emergency policies. While citizens and organizations developed various coping and circumventing strategies, Boko Haram evolved from an open network model of insurgency to a closed centralized system, shifting the center of its operations to the Sambisa Forest. This fundamentally changed the dynamics of the conflict. [187]

In July 2014, Nigeria was estimated to have had the highest number of terrorist killings in the world over the past year, 3477, killed in 146 attacks.[188] The governor of Borno, Kashim Shettima, of the opposition ANPP, said in February 2014:[189]

Boko Haram are better armed and are better motivated than our own troops. Given the present state of affairs, it is absolutely impossible for us to defeat Boko Haram.

International responses

Designation as a terrorist organization

| Country | Date | References |

|---|---|---|

| 20 August 2012 | [190] | |

| 10 July 2013 | [191][192] | |

| 14 November 2013 | [193] | |

| 24 December 2013 | [194] | |

| 22 May 2014 | [195] | |

| 26 June 2014 | [196] | |

| 15 November 2014 | [197] |

United States responses

The U.S. State Department designated Boko Haram and Ansaru as terrorist organisations in November 2013, citing various reasons including links with AQIM, "thousands of deaths in north-east and central Nigeria over the last several years, including targeted killings of civilians", and Ansaru's 2013 kidnapping and execution of seven international construction workers. In the statement it was noted, however, "These designations are an important and appropriate step, but only one tool in what must be a comprehensive approach by the Nigerian government to counter these groups through a combination of law enforcement, political, and development efforts."[198][199] The State Department had resisted earlier calls to designate the group as a terrorist organisation after the 2011 UN bombing.[200] The U.S. government does not believe Boko Haram is currently (2014) affiliated with al Qaeda Central, despite regular periodic pledges of support and solidarity from its leadership for al-Qaeda, but is particularly concerned about ties between Boko Haram and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), including "likely sharing funds, training, and explosive materials", [31]

Efforts to cooperate in freeing the Chibok schoolgirls had faltered, largely due to mutual distrust; the infiltration of the military by Boko Haram meant that U.S. officials were wary of sharing raw intelligence data, and the Nigerian military had failed to supply information that might have aided U.S. drone flights in locating the kidnapped girls. The Nigerian government claims that Boko Haram is "the West Africa branch of the world-wide Al-Qaida movement with connections with Al'shabb [sic] in Somalia and AQIM in Mali". They deny having committed human rights abuses in the conflict, and therefore oppose U.S. restrictions on arms sales, which they see as being based on the U.S. mis-application of the Leahy Law due to concerns over human rights in Nigeria. The U.S. had supplied the Nigerian army with trucks and equipment but had blocked the sale of Cobra helicopters. In November 2014 the U.S. State department again refused to supply Cobras, citing concerns over the Nigerian military's ability to maintain and use them without endangering civilians.[201][202][203][204]

On 1 December 2014 the U.S. embassy in Abuja announced that the U.S. had discontinued training a Nigerian battalion at the request of the Nigerian government. A spokesman for the U.S. state department said, "We regret premature termination of this training, as it was to be the first in a larger planned project that would have trained additional units with the goal of helping the Nigerian Army build capacity to counter Boko Haram. The U.S. government will continue other aspects of the extensive bilateral security relationship, as well as all other assistance programs, with Nigeria. The U.S. government is committed to the long tradition of partnership with Nigeria and will continue to engage future requests for cooperation and training."[204][205]

African Coalition force

After a series of meetings over many months,[2][3][4] Cameroon's foreign minister announced on 30 November 2014 that a coalition force to fight terrorism, including Boko Haram, would soon be operational. The force would include 3,500 soldiers from Benin, Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria.[206][207] Discussions between the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) about a broader based military force have been scheduled.[208]

French and British assistance

France and the UK, in coordination with the United States, have sent trainers, and material assistance to Nigeria to assist in the fight against Boko Haram.[209] France planned to use 3,000 troops in the region for counter-terrorism operations. Israel and Canada also pledged support.[210]

Chinese assistance

In May 2014, China offered Nigeria assistance that included satellite data and potentially military equipment.[209]

See also

- Islamic extremism in Northern Nigeria

- Timeline of Boko Haram insurgency

- Human rights in Nigeria

- Nigerian Mobile Police

References

- ^ a b c d e f Bureau of Counterterrorism. "Country Reports on Terrorism 2013". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d http://www.ngrguardiannews.com/news/national-news/187812-five-lake-chad-region-nations-meet-over-boko-haram

- ^ a b c d "Jonathan tasks Defence, Foreign Ministers of Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon, Niger, Benin on Boko Haram's defeat". sunnewsonline.com.

- ^ a b c d Martin Williams. "African leaders pledge 'total war' on Boko Haram after Nigeria kidnap". The Guardian.

- ^ "Chadian Forces Deploy Against Boko Haram". VOA. 16 January 2015. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "How Big Is Boko Haram?". 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ a b c "Are Boko Haram Worse Than ISIS?". Conflict News.

- ^ a b c d "Global Terrorism Index 2014" (PDF). Institute for Economics and Peace. p. 53. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ^ "Al-Qaeda map: Isis, Boko Haram and other affiliates' strongholds across Africa and Asia". 12 June 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2014., see interactive infographic

- ^ "Boko Haram voices support for ISIS' Baghdadi". Al Arabiya. 13 July 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "EXCLUSIVE: Boko Haram pledges baya to the Islamic State". 7 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ "Boko Haram insurgents kill 100 people as they take control of Nigerian town". The Guardian. 19 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria Security Tracker". www.cfr.org. Council of Foreign Relations. 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Boko Haram". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved September 2014.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Glenn Kessler (19 May 2014). "Boko Haram: Inside the State Department debate over the 'terrorist' label". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Nigeria: Boko Haram Attacks Likely Crimes Against Humanity". Human Rights Watch. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram unrest: Gunmen kidnap Nigeria villagers". BBC. 3 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Boko Haram Kidnap Dozens Of Boys In Northeast Nigeria: Witnesses". The Huffington Post. 15 July 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Nigeria: Victims of Abductions Tell Their Stories". Human Rights Watch. 27 October 2014. Retrieved November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Islamists force 650 000 Nigerians from homes". News 24. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram Overruns Villages and Army Base in Northeast Nigeria". The Wall Street Journal. 5 January 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Boko Haram is now a mini-Islamic State, with its own territory". The Telegraph. 10 January 2015.

- ^ Department of Public Information • News and Media Division (22 May 2014). "Security Council Al-qaida Sanctions Committee Adds Boko Haram to its Sanctions List". New York: UN Security Council. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e U.S. Embassy, Abuja (4 November 2009). "Nigeria: Borno State Residents Not Yet Recovered From Boko Haram Violence". Wikileaks. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ http://www.gamji.com/tilde/tilde99.htm

- ^ a b c George Percy Bargery (1934). "Hausa-English dictionary". Lexilogos. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ a b Paul Newman (2013). "The Etymology of Hausa boko" (PDF). Mega-Chad Research Network. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria committing 'war crimes' to defeat Boko Haram". The Independent. 17 August 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ William F. S. Miles (9 May 2014). "Breaking Down 'Boko Haram'". cognoscenti.

- ^ Dr. Aliyu U. Tilde. "An in-house Survey into the Cultural Origins of Boko Haram Movement in Nigeria". Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d Lauren Ploch Blanchard (10 June 2014). "Nigeria's Boko Haram: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b Johnson, Toni (27 December 2011). "Backgrounder - Boko Haram". www.cfr.org. Council of Foreign Relations. Retrieved 12 March 2012. Cite error: The named reference "cfrBackgrounder" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Cook, David (26 September 2011). "The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria". Combating Terrorism Centre. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ "The Diffusion of Intra-islamic Violence and Terrorism: the Impact of the Proliferation of Salafi/Wahhabi Ideologies". Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "sunnicity.com". Retrieved 10 November 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Onuoha, Freedom (2014). "Boko Haram and the evolving Salafi Jihadist threat in Nigeria". In Pérouse de Montclos, Marc-Antoine (ed.). Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria (PDF). Leiden: African Studies Centre. pp. 158–191. ISBN 978-90-5448-135-5. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ^ "African Arguments Editorial – Boko Haram in Nigeria : another consequence of unequal development". African Arguments. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Bartolotta, Christopher (23 September 2011). "Terrorism in Nigeria: the Rise of Boko Haram". The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Zainab Usman (1 May 2014). "Nigeria's Economic Transition Reveals Deep Structural Distortions". African Arguments. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Data". The World Bank. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigerians living in poverty rise to nearly 61%". BBC. 13 February 2012. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c Adesoji, Abimbola (2010). "The Boko Haram Uprising and Islamic Revivalism in Nigeria". Africa Spectrum. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "USCIRF Annual Report 2013 - Thematic Issues: Severe religious freedom violations by non-state actors". UNHCR. 30 April 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Barnaby Phillips (20 January 2000). "Islamic law raises tension in Nigeria". BBC. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Article 7: Right to equal protection by the law". BBC World Service. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Gérard L. F. Chouin, Religion and bodycount in the Boko Haram crisis: evidence from the Nigeria Watch database, p. 214. ISBN 978-90-5448-135-5

- ^ Adebayo, Akanmu G, ed. (2012). Managing Conflicts in Africa's Democratic Transitions. Lexington Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0739172636.

- ^ West African Studies Conflict over Resources and Terrorism. OECD. 2013.

- ^ J. Peter Pham (19 October 2006). "In Nigeria False Prophets Are Real Problems". World Defense Review. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria's 'Taliban' enigma". BBC News. 28 July 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ^ "Africa in Transition". Council on Foreign Relations - Africa in Transition.

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. "Influence of Christian Missions", Nigeria: A Country Study], Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991, accessed 18 April 2012

- ^ a b Chothia, Farouk (11 January 2012). "Who are Nigeria's Boko Haram Islamists?". BBC News. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ Ijeaku, N.J.O. (2009). The Igbo and Their Niger Delta Neighbors: We Are No Second Fools. Xlibris Corporation. pp. 82–83. ISBN 9781462808618.

- ^ Martin Meredith (2011). "5. Winds of Change". The State of Africa: A History of the Continent Since Independence (illustrated ed.). Simon and Schuster. p. 77. ISBN 9780857203892.

- ^ a b Martin Ewi (24 June 2013). "Why Nigeria needs a criminal tribunal and not amnesty for Boko Haram". Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Kirk Ross (19 May 2014). "Revolt in the North: Interpreting Boko Haram's war on western education". African Arguments. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Analysis: Understanding Nigeria's Boko Haram radicals". www.irinnews.org. 18 July 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Whose faith, whose girls?". The Economist.

- ^ "Nigeria accused of ignoring sect warnings before wave of killings". The Guardian. London. 2 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ^ Joe Bavier (15 January 2012). "Nigeria: Boko Haram 101". Pulitzercenter.org.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (27 July 2009). "Scores Die as Fighters Battle Nigerian Police". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Nigeria sect head dies in custody". BBC. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria killings caught on video – Africa". Al Jazeera English. 10 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Boko Haram attacks – timeline". The Guardian. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Peace and Security Council Report" (PDF). ISS. February 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Ndahi Marama (30 July 2014). "UN House bombing: Why we struck-Boko Haram". Vanguard. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Counterterrorism 2014 Calendar". The National Counterterrorism Center. 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Ibrahim Mshelizza (29 August 2011). "Islamist sect Boko Haram claims Nigerian U.N. bombing". Reuters. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ Joe Brock (31 January 2012). "Special Report: Boko Haram - between rebellion and jihad". Reuters. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b Richard Dowden (9 March 2012). "Boko Haram – More Complicated Than You Think". Africa Arguments. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ David Cook (26 September 2011). "The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria". Combating Terrorism Center. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram attacks an air base in Nigeria". Aljazeera. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram claims responsibility for bomb blasts in Bauchi, Maiduguri". Vanguard News. 1 June 2011. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Olalekan Adetayo (9 January 2012). "Boko Haram has infiltrated my govt –Jonathan". Punch. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ David Cook (26 September 2011). "The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria". Combating Terrorism Center. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ a b Jean Herskovits (2 January 2012). "In Nigeria, Boko Haram Is Not the Problem". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Olly Owen (19 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Answering Terror With More Meaningful Human Security". African Arguments. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Olly Owen (19 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Answering Terror With More Meaningful Human Security". African Arguments. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Gernot Klantschnig (February 2012). "Review of the January 2012 UK Border Information Service Nigeria Country of Origin Information Report" (PDF). Independent Advisory Group on Country Information. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor. "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Boko Haram Attacks Likely Crimes Against Humanity". Human Rights Watch. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Ibanga Isine (27 June 2014). "High-level corruption rocks $470million CCTV project that could secure Abuja". Premium Times. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Duncan Gardham; Laura Heaton (25 December 2011). "Coordinated bomb attacks across Nigeria kill at least 40". The Telegraph. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Five bombs explode across Nigeria killing dozens". Buenos Aires Herald. 25 December 2011. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Adam Nossiter (25 December 2011). "Nigerian Group Escalates Violence With Church Attacks". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tina Moore (25 December 2011). "Christmas Day bombings in Nigeria kill at least 39, radical Muslim sect claims responsibility". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria churches hit by blasts". Aljazeera. 26 December 2011. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Christmas bombings kill many near Jos, Nigeria". BBC. 25 December 2010. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Felix Onuah; Tim Cocks (31 December 2011). "Nigeria's Jonathan declares state of emergency". Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigerian fuel subsidy: Strike suspended". BBC. 16 January 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Post-Election Violence Killed 800". Human Rights Watch. 17 May 2011. Retrieved November 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ David Blair (5 February 2012). "Al-Qaeda's hand in Boko Haram's deadly Nigerian attacks". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ a b Mike Oboh (22 January 2012). "Islamist insurgents kill over 178 in Nigeria's Kano". Reuters. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigerians offer prayers in Kano for suicide bombers' victims". The Guardian. Associated Press. 23 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria's Kano rocked by multiple explosions". BBC. 21 January 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ Taye Obateru; Grateful Dakat (22 January 2012). "Boko Haram: Fleeing Yobe Christians". Vanguard. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: Boko Haram Widens Terror Campaign". Human Rights Watch. 24 January 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (2012). "Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "With cross-border attacks, Boko Haram threat widens". IRIN. 21 November 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Tim Cocks (30 May 2014). "Cameroon weakest link in fight against Boko Haram". Reuters. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Nigeria: FG Inaugurates Nigeria-Cameroon Trans-Border Security Committee". allAfrica. 5 February 2013. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "2nd session of Nigeria/Cameroon Trans-Border Security Committee meets in Abuja". Daily Independent. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria-Cameroon security committee meets". News 24 Nigeria. 2014-07-07. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria: Deaths of hundreds of Boko Haram suspects in custody requires investigation". Amnesty International. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Operational Guidance Note" (PDF). Home Office. December 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ "650,000 Nigerians Displaced Following Boko Haram Attacks – UN". Information Nigeria. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Adrian Edwards (9 May 2014). "Refugees fleeing attacks in north eastern Nigeria, UNHCR watching for new displacement". UNHCR. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Emele Onu (5 August 2014). "Amnesty Says 'Gruesome' Nigerian Footage Shows War Crimes". Bloomberg. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Ries, Brian (6 May 2014). "Bring Back Our Girls: Why the World Is Finally Talking About Nigeria's Kidnapped Students". Mashable. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ Litoff, Alyssa (6 May 2014). "Home> International 'Bring Back Our Girls' Becomes Rallying Cry for Kidnapped Nigerian Schoolgirls". ABC News. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ^ "Rewards for Justice - First Reward Offers for Terrorists in West Africa". U.S. Department of State. 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Nigeria says 219 girls in Boko Haram kidnapping still missing". Fox News. 23 June 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Maria Tadeo (10 May 2014). "Nigeria kidnapped schoolgirls: Michelle Obama condemns abduction in Mother's Day presidential address". The Independent. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Tim Cocks (8 July 2014). "Jonathan's PR offensive backfires in Nigeria and abroad". Yahoo! News/Reuters. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Megan R. Wilson (2014-06-26). "Nigeria hires PR for Boko Haram fallout". The Hill. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Nigeria: Government knew of planned Boko Haram kidnapping but failed to act". Amnesty International UK. 9 May 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Taiwo Ogunmola Omilani (24 July 2014). "Chibok Abduction: NANS Describes Jonathan As Incompetent". Leadership, Nigeria. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "One month after Chibok girls' abduction". The Nation, Nigeria. 15 May 2014. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Daniel Magnowski (10 September 2014). "Nigeria's President Jonathan Bans 'Bring Back Goodluck' Campaign". Bloomberg. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ Felix Onuah (11 November 2014). "Nigeria's Jonathan seeks second term, vows to beat Boko Haram". Reuters. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Emmanuel Tummanjong (17 May 2014). "Chinese Workers Kidnapped by Suspected Boko Haram Militants in Cameroon". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ Natasha Culzac (11 October 2014). "Boko Haram releases 27 hostages including Deputy PM's wife, Cameroon says". The Independent. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ^ "Boko Haram plans more attacks, recruits many young people". Vanguard. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ "'Islamist militants' kill 10 in northern Cameroon". BBC. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ Haruna Umar (7 August 2014). "Boko Haram takes Nigeria town, resident says". Yahoo! News. Retrieved August 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Cameroon receives 8,000 refugees fleeing Boko Haram in Nigeria". Nigerian Tribune. 13 July 2014. Retrieved August 2014.