Salem, Massachusetts: Difference between revisions

DTParker1000 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (22 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

[[File:Salem Harbor Fitz Hugh Lane.jpeg|thumb|''Salem Harbor'', oil on canvas, [[Fitz Hugh Lane]], 1853. [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]].]] |

[[File:Salem Harbor Fitz Hugh Lane.jpeg|thumb|''Salem Harbor'', oil on canvas, [[Fitz Hugh Lane]], 1853. [[Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]].]] |

||

During the [[American Revolution]], the town became a center for [[privateer]]ing. Although the documentation is incomplete, about 1,700 [[Letters of Marque]], issued on a per-voyage basis, were granted during Revolution. Nearly 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers, and are credited with capturing or destroying about 600 British ships.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/privateers.html|title=John Fraylor. Salem Maritime National Historic Park|publisher=Nps.gov|accessdate=2012-09-03}}</ref> During the [[War of 1812]], privateering resumed. |

During the [[American Revolution]], the town became a center for [[privateer]]ing. Although the documentation is incomplete, about 1,700 [[Letters of Marque]], issued on a per-voyage basis, were granted during Revolution. Nearly 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers, and are credited with capturing or destroying about 600 British ships.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/privateers.html|title=John Fraylor. Salem Maritime National Historic Park|publisher=Nps.gov|accessdate=2012-09-03}}</ref> During the [[War of 1812]], privateering resumed. |

||

==War of 1812 and the Essex Junto == |

|||

In the winter of 1803-1804, a group of Federalist congressmen plotted to establish a "Northern Confederacy" consisting of New Jersey, New York, New England, and Canada, to be established with the support of Britain, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton. When traction was not found with the Adams and Hamilton the conspirators turned to Vice President Aaron Burr. With Burr on trial for [[Burr Conspiracy]] they would loose the support of New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. In Massachusetts the scheme started in Ipswich but quickly moved to Salem by the [[Essex Junto]] headed by [[Timothy Pickering]] who had served for Washington and Adams as Secretary of State. Along with [[Daniel Webster]], [[George Cabot]], [[William Prescott Jr.]], and [[Nathan Dane]] Pickering made loud threats that were noticed by [[Samuel Adams]], [[Thomas Jefferson]], and [[Joseph Story]] in their various letters. During the [[War of 1812]] Massachusetts pulled all military and financial support from the war and built their own standing forces with the threat of siding with the British who already took over what was then territory of Massachusetts, Maine. In Salem they re-outfitted the old hill fort and rename it [[Fort Pickering]] in preparation for the defense of the British once they ventured south of Maine. Webster, Pickering, Prescott, and Cabot headed south to Hartford Connecticut for a convention with threats of secession. The [[Hartford Convention]] ended up to be a comedy of errors for in Ghent the treaty was signed that ended the War. Also by the time they arrived in Washington D.C. news had arrived that Jackson and Lafitte had defeated Wellington's army in New Orleans. This could of been a serious wound to the new country, but President Monroe did a tour of New England in 1817 to heal the wounds of the Hartford Convention as the Federalist Party dissolved, for a little while later reforming as the Whig Party, but for a short time Monroe succeeded in unifying the country into a one party system and removed the specter of the collapse of the country.<ref>{{cite url |title=THE NORTHERN CONFEDERACY ACCORDING TO THE PLANS OF THE "ESSEX JUNTO ^' 1796-1814 |author=Charles Raymond Brown |url=https://archive.org/stream/northconfed00brownrich/northconfed00brownrich_djvu.txt |access-date=6 September 2017 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Sub Rosa |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2017}}</ref> |

|||

==Trade with the Pacific and Africa== |

==Trade with the Pacific and Africa== |

||

| Line 120: | Line 123: | ||

==Legacy of the East Indies and Old China Trade== |

==Legacy of the East Indies and Old China Trade== |

||

{{further information|Peabody Academy of Science}} |

{{further information|Peabody Academy of Science}} |

||

The [[Old China Trade]] left a significant mark in two historic districts, [[Chestnut Street District]], part of the [[Samuel McIntire]] Historic District containing 407 buildings, and the [[Salem Maritime National Historic Site]], consisting of 12 historic structures and about 9 acres (36,000 m²) of land along the waterfront in Salem. [[Elias Hasket Derby]] was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary merchants in Salem. Derby was also the owner of the Grand Turk, the first New England vessel to trade directly with [[China]]. Thomas Perkins was his supercargo and established strong ties with the Chinese and garnered the Forbes fortune through his illegal opium sales. |

The [[Old China Trade]] left a significant mark in two historic districts, [[Chestnut Street District]], part of the [[Samuel McIntire]] Historic District containing 407 buildings, and the [[Salem Maritime National Historic Site]], consisting of 12 historic structures and about 9 acres (36,000 m²) of land along the waterfront in Salem. [[Elias Hasket Derby]] was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary merchants in Salem. Derby was also the owner of the Grand Turk, the first New England vessel to trade directly with [[China]] and second to sail from America after the <i>Empress of China</i>. Thomas H. Perkins was his supercargo and established strong ties with the Chinese and garnered the Forbes fortune through his illegal opium sales. |

||

Salem was incorporated as a city on March 23, 1836,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.salempd.org/history.htm |title=Salem history |publisher=Salempd.org |date=2010-05-13 |accessdate=2012-11-10 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130112082322/http://www.salempd.org/History.htm |archivedate=2013-01-12 |df= }}</ref> and adopted a city seal in 1839 with the motto "''Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum''", [[Latin]] for "To the rich East Indies until the last lap." [[Nathaniel Hawthorne]] was overseer of Salem's port from 1846 until 1849. He worked in the U.S. Customs House across the street from the port<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.salemweb.com/guide/tour/attract5.shtml |title=Salem Massachusetts - Sites and Attractions Tour |publisher=Salemweb.com |accessdate=2012-09-03}}</ref> near Pickering Wharf, his setting for the beginning of ''[[The Scarlet Letter]]''. In 1858, an [[amusement park]] was established at Juniper Point, a peninsula jutting into the harbor. Prosperity left the city with a wealth of fine architecture, including [[Federal architecture|Federal-style]] mansions designed by one of America's first [[architect]]s, [[Samuel McIntire]], for whom the city's largest historic district is named. These homes and mansions now comprise the greatest concentrations of notable pre-1900 domestic structures in the United States. |

Salem was incorporated as a city on March 23, 1836,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.salempd.org/history.htm |title=Salem history |publisher=Salempd.org |date=2010-05-13 |accessdate=2012-11-10 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20130112082322/http://www.salempd.org/History.htm |archivedate=2013-01-12 |df= }}</ref> and adopted a city seal in 1839 with the motto "''Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum''", [[Latin]] for "To the rich East Indies until the last lap." [[Nathaniel Hawthorne]] was overseer of Salem's port from 1846 until 1849. He worked in the U.S. Customs House across the street from the port<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.salemweb.com/guide/tour/attract5.shtml |title=Salem Massachusetts - Sites and Attractions Tour |publisher=Salemweb.com |accessdate=2012-09-03}}</ref> near Pickering Wharf, his setting for the beginning of ''[[The Scarlet Letter]]''. In 1858, an [[amusement park]] was established at Juniper Point, a peninsula jutting into the harbor. Prosperity left the city with a wealth of fine architecture, including [[Federal architecture|Federal-style]] mansions designed by one of America's first [[architect]]s, [[Samuel McIntire]], for whom the city's largest historic district is named. These homes and mansions now comprise the greatest concentrations of notable pre-1900 domestic structures in the United States. |

||

Shipping declined throughout the 19th century. Salem and its [[silt]]ing harbor were increasingly eclipsed by nearby [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]] and [[New York City]]. Consequently, the city turned to manufacturing. Industries included [[Tanning (leather)|tanneries]], shoe factories, and the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company. More than 400 homes were destroyed in the [[Great Salem Fire of 1914]], leaving 3,500 families homeless from a blaze that began in the Korn Leather Factory at 57 Boston Street. The historic concentration of Federal architecture on Chestnut Street were spared from destruction by fire, in which they still exist to this day. A memorial plaque currently exists where the Korn Leather Factory once stood, on what is now a [[Walgreens]] store. |

Shipping declined throughout the 19th century. Salem and its [[silt]]ing harbor were increasingly eclipsed by nearby [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]] and [[New York City]]. Consequently, the city turned to manufacturing. Industries included [[Tanning (leather)|tanneries]], shoe factories, and the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company. More than 400 homes were destroyed in the [[Great Salem Fire of 1914]], leaving 3,500 families homeless from a blaze that began in the Korn Leather Factory at 57 Boston Street. The historic concentration of Federal architecture on Chestnut Street were spared from destruction by fire, in which they still exist to this day. A memorial plaque currently exists where the Korn Leather Factory once stood, on what is now a [[Walgreens]] store. |

||

===Derby Tunnels=== |

|||

[[File:Elias Hasket Derby Jr 2.jpg|thumb|left|Elias Hasket Derby, Jr.]] In 1801, Elias Hasket Derby, Jr. extended the tunnel system in [[Salem, Massachusetts]], in response to [[Thomas Jefferson]]'s new custom duties.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=97xglLJM8WcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false |title=Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City |publisher=Salem House Press |access-date=2014-03-01}}</ref> Jefferson had ordered the local militias to help collect these duties, but in Salem, Derby had hired the local militia (later the United States' first [[National Guard of the United States|National Guard]] unit), the [[101st Engineer Battalion (United States)|101st Engineer Battalion]], to dig the tunnels and hide the spoils in five ponds in the local common. |

|||

This extension was funded by the [[Salem Common Historic District (Salem, Massachusetts)|Salem Common]] Improvement Fund, whose members included Supreme Court Justice [[Joseph Story]], Secretary of the Navy [[Benjamin Crowninshield]], Congressman [[Jacob Crowninshield]], Senator [[Nathaniel Silsbee]], lawyer [[Daniel Webster]], Senator [[William Gray (Massachusetts)|William Gray]], Senator [[Benjamin Pickman, Jr.]], and the London banker and [[JPMorgan Chase]] founder [[George Peabody]]. |

|||

Salem's head of customs, Joseph Hiller, was also a member, as was Benjamin Crowninshield, head of customs for [[Marblehead, Massachusetts]]. Presidents [[George Washington]], [[James Monroe]], and [[John Quincy Adams]] might have walked in the tunnels as well. At a minimum, they visited many homes that were connected to the tunnels, and John Quincy Adams dedicated the [[East India Marine Hall]], which had four sub-basements and was connected to the tunnels.<ref>{[cite book |title=Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2012}}</ref> |

|||

The [[East India Marine Society]] Museum had many locations in town that were connected to the tunnels. The society became the [[Peabody Academy of Science]] with the support of Joseph Peabody, and the tunnels became part of the [[Peabody Essex Museum]] after it merged with the Essex Institute in 1992. |

|||

The Essex Institute — established by [[Edward Augustus Holyoke]], founder of the ''[[The New England Journal of Medicine]] —'' was also connected to the tunnels. |

|||

The tunnels were used by [[Charles Lenox Remond]] to move runaway slaves along the [[Underground Railroad]]. They were also used to transport illicit liquor during the [[Prohibition|Prohibition Era]]. |

|||

The tunnels extended three miles from the town's wharfs to an underground train station built by the superintendent of the [[Eastern Railroad (Massachusetts)|Eastern Railroad]], [[John Kinsman]]. Along the way, they connected several homes, stores, and banks. Two large brick homes were built at fixed distances to conceal the purchases of bricks needed for the tunnel. Many large churches were made out of bricks for the same reason.<ref>{[cite book |title=Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2012}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Daniel Lowe Tunnel.jpg|thumb|right|Tunnel under the first church in the country]] |

|||

[[File:Charles Bulfinch.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Charles Bulfinch]][[Samuel McIntire]] fashioned the [[Federal architecture|Federal style of architecture]] after [[Charles Bulfinch]], who would become the [[architect of the Capitol]]. In both of these men's designs, homes had exterior chimneys that connected to the tunnels through watertight fireplace arches. |

|||

These arches and their flues provided not only a dry entrance to the homes but also a draw system up through the chimneys for the tunnels. Bulfinch connected his Looby Asylum, Essex Bank Building, and Old Town Hall to the tunnels in Salem. He would also build tunnels from the State House in Boston and the [[National Capitol]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.salemtunneltour.com |title=salem Smugglers' Tour |publisher=salem Smugglers' Tour |access-date=1 January 2014}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- EDITORIAL NOTE: Following was moved from Tunnels article, where it gave undue weight to this topic. This text should be merged here.--> |

|||

[[File:Iron Door in the Smuggling tunnel in Salem, Ma..jpg|thumb|alt=Picture of tunnel on the Salem Tunnel Tour|Iron door blocking off smuggling tunnels under the Downing Block in [[Salem, Massachusetts]]]] |

|||

Smuggling tunnels are common in most New England seaports. These towns relied on imports and had built tunnels in response to Jefferson's new custom duties. In places like [[New Londondery, New Hampshire]], [[Marblehead, Massachusetts]], and Salem, the heads of customs turned a blind eye to the smugglers. [[Joseph Hiller]] was the head of customs in Salem. He was the Master Mason of the [[Essex Lodge]] and a conspirator in the Salem Common Improvement Fund.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=97xglLJM8WcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Salem Secret Underground: The History of the Tunnels in the City |access-date=12 January 2012}}</ref> The fund was a subterfuge to underwrite a massive tunnel spanning three miles, used to avoid paying Jefferson's new custom duties in 1801. Another member of the fund was Secretary of the Navy [[Benjamin Crowninshield]], who was head of customs in Marbelhead. In fact the Custom House in Salem was built atop the basement of his father's house, with the old tunnels still leading to it. (Crowninshield's father, George Crowninshield, started the Boston Brahmin [[Crowninshield family]].) Benjamin Crowninshield's home was also connected. President [[James Monroe]] visited his home plus many others in town that were connected to the tunnel. <ref>{{cite book |title=Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2012}}</ref><ref> {{cite web |title=The History of Presidential Visits to Salem |url=https://patch.com/massachusetts/salem/u-s-presidents-in-salem |access-date=6 September 2017}}</ref> |

|||

[[George Washington]] celebrated his birthday in Assembly Hall in town and slept in the [[Joshua Ward House]]. Both buildings were connected to the tunnels. |

|||

[[John Quincy Adams]] lectured at the [[Salem Lyceum]], visited the banker Joseph Peabody, dedicated the East India Marine Hall, and was entertained at Hamilton Hall. All of those buildings were connected to the tunnels. |

|||

Others who used the tunnels included: |

|||

*The murderer of [[Joseph White]] in 1830. |

|||

*The Parker brothers, who inherited the wealth left to them by their father, Colonel William Parker, who utilized those tunnels extensively. |

|||

*[[Charles Lenox Remond]] used the tunnels to transport runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad. The tunnels even connected the sea to an Underground Railroad station. |

|||

The tunnels were extended by Elias Hasket Derby, Jr. His father, [[Elias Hasket Derby]], Sr., was America's first millionaire and the most successful owner of a fleet of privateers during the [[American Revolutionary War]]. |

|||

The Architect of the Capitol [[Charles Bulfinch]] built the Looby Asylum, Old Town Hall, and the Essex Bank Building in Salem, which all connected to the tunnels. Old Town Hall was built on the site of Elias Hasket Derby's last mansion in town. This was the money pit that spurred his son to dig tunnels to support it. After it was demolished Bulfinch had built Old Town Hall on its location, extending the tunnel entrances to it. |

|||

One of the oldest elite societies in America, the Salem Marine Society, had tunnels leading into their building where the [[Hawthorne Hotel]] is now. They still have their club house on top of the building. They received the deed from the opium dealer [[Thomas Handasyd Perkins]]. Their sister organization, the Salem East India Marine Society (founded by Jonathan and John Hodges), created a museum which would eventually merge with the Essex Institute (which was founded by [[Edward Augustus Holyoke]]). Both museums have been connected to the tunnels for over 200 years. |

|||

The Hodges' home actually connected to Elias Hasket Derby's home. The East India Marine Society Museum would be renamed the Peabody Academy of Science, after Joseph Peabody found they were near destitution. In 1992, the two museums merged to create the Peabody Essex Museum. |

|||

In later years the tunnels were used during Prohibition. Bunghole Liquors, which received the second liquor license in town after Prohibition, has a basement that was a [[speakeasy]] hidden under a funeral home, and that basement is attached to the tunnels.<ref>{{cite web|title=History |url=http://salemtunneltour.com/History.html |access-date=24 January 2014}</ref> |

|||

==Inventions== |

|||

Many inventors lived in Salem. [[Moses Farmer]] was the first to light his home by electricity and sold his lightbulb to [[Thomas Edison]]. Edison also used his arc lighting in his demonstrations. Farmer provided Tesla with his lightbulbs for [[Westinghouse]] after Edison refused to sell them his to light the [[Columbian Exposition]] World Fair of 1893. Farmer would die at the fair. [[Charles Grafton Page]] made an electromagnet that could lift 1,000 pounds, electric train, an early telegraph, and worked in the US patent office. He was a precursor to what would befall Tesla for his laboratory had burned down during the Civil War and the section of the Smithsonian which housed his magnet also burned at a later date. [[Joseph Dixon]] the inventor of high temperature graphite crucibles, the Single Reflex Lens, and the Dixon-Ticonderoga #2 pencil lived in Salem. Packard Electric were making electric cars in the nineteenth century up to the 1914 fire which destroyed their factory. [[Alexander Graham Bell]] invented the phone in Salem and held the first public demonstration at the Salem Lyceum Hall. Also [[Nicola Tesla]] would create a power plant for Pequot Mills. He was in the area after [[Mark Twain]] introduced him to [[John Hammond Sr.]]. Tesla would give his son, [[John Hammond Jr.]] the patents for remote control which Hammond used to develop guided missiles and boats for the military during WWII. Tesla would conduct tests on ESP at [[Hammond Castle]] using a [[Faraday Cage]] to prove ESP did not transmit through electromagnetic waves, for a psychic received a message from a woman in the cage a few miles away. It was John Hammond Sr. who helped destroy Tesla's plans for free wireless electricity since he just invested heavily in a copper mine that was going to create electrical lines for transmission. Also [[Elihu Thomson]] had his [[Thomson-Houston Electric Company]] in the bordering town of Lynn and lived in the other border town Swampscott. This company will be merged with [[Edison Electric Company]] to make [[General Electric]]. Many of these Salem inventors' inventions are still displayed in the [[Smithsonian]] in the electricity display room. |

|||

==Air Station and the National Guard== |

==Air Station and the National Guard== |

||

| Line 397: | Line 444: | ||

* [[John Tucker Daland House]] (1851) |

* [[John Tucker Daland House]] (1851) |

||

* [[Joseph Story House]] |

* [[Joseph Story House]] |

||

* White-Lord House (1811) 31 Washington Square, built from bribes by Baring Brothers Bank to build the Second Bank of the United States. President Jackson visited this home during the Bank Wars in 1833. Also President Monroe was entertained here in July of 1817 with Charles Bulfinch. Built by William Roberts who built the East India Marine Hall. One of many locations connected to the tunnels of Salem. |

|||

*[[Gardner-Pingree House]] (1804) Built by Samuel McIntire. Owned by Captain Joseph White who was murdered in the home in 1830 by his nephew Stephen White. It is the basis for the mansion in the [[Parker Brothers]] game [[Clue]]. Also connected to the tunnels in Salem. |

|||

* [[Chestnut Street District]], also known as the McIntire Historic District,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.salemweb.com/guide/arch/mdistrict.shtml|title=Salem Massachusetts - Salem Architecture Salem Architecture: McIntire|work=salemweb.com}}</ref> greatest concentration of 17th and 18th century domestic structures in the U.S. |

* [[Chestnut Street District]], also known as the McIntire Historic District,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.salemweb.com/guide/arch/mdistrict.shtml|title=Salem Massachusetts - Salem Architecture Salem Architecture: McIntire|work=salemweb.com}}</ref> greatest concentration of 17th and 18th century domestic structures in the U.S. |

||

* [[First Church in Salem]], Unitarian Universalist, founded in 1629. |

* [[First Church in Salem]], Unitarian Universalist, founded in 1629. |

||

* John Hodges House (1788) Built for the founder of the Salem East India Marine Society who founded what is now the Peabody Essex Museum. This home and the museum were connected to the tunnels in Salem. |

|||

* [[Derby House]] (1762) First brick house built in Salem after another man had died of a cold who lived in a brick home. Home of America's first millionaire ranked the 10th richest in history. Connected to the John Hodges House by a tunnel. |

|||

* [[Misery Islands]] |

* [[Misery Islands]] |

||

* [[Nathaniel Bowditch House]] (c. 1805), home of the founder of modern navigation |

* [[Nathaniel Bowditch House]] (c. 1805), home of the founder of modern navigation |

||

| Line 414: | Line 465: | ||

* [[Winter Island]], park and historic point of the U.S. Coast Guard in WW2 for [[U-boat]] patrol |

* [[Winter Island]], park and historic point of the U.S. Coast Guard in WW2 for [[U-boat]] patrol |

||

* [[The Witch House]], the home of the [[Salem witch trials]] investigator [[Jonathan Corwin]], and the only building still standing in Salem with direct ties to the witch trials |

* [[The Witch House]], the home of the [[Salem witch trials]] investigator [[Jonathan Corwin]], and the only building still standing in Salem with direct ties to the witch trials |

||

*Daniel Low & Co. Building (1826) Originally built for the First Church. Later owned by jeweler Daniel Low. Connected to the tunnels in Salem. This passage is still open leading to Low's warehouse behind. In the floor of the tunnel are buried runaway slaves. Daniel Low knowing that they were there and the State wanted to commemorated them sealed the floor of the tunnel in concrete before they could he invented the souvenir spoon and sold KKK belt buckles. |

|||

===Salem points of interest=== |

===Salem points of interest=== |

||

| Line 446: | Line 498: | ||

* [[Frederick M. Davenport]] (1866-1956), US Congressman |

* [[Frederick M. Davenport]] (1866-1956), US Congressman |

||

* [[Elias Hasket Derby]] (1739–1799), merchant, first millionaire<ref>http://gravematter.smugmug.com/gallery/1499497/1/71888985/Large</ref> |

* [[Elias Hasket Derby]] (1739–1799), merchant, first millionaire<ref>http://gravematter.smugmug.com/gallery/1499497/1/71888985/Large</ref> |

||

* Elias Hasket Derby Jr. (1766-1826) General of Second Corp Cadets, Engineer of extending the smuggling tunnels in Salem, inventor of first broadcloth loom in America. <ref>{{cite book | title=Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City |author= Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2012 |isbn=978-0983666554}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Joseph Story]] (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) Associate Superior Court Justice, First Dean of Harvard Law School, brother-in-law to Stephen White, director of Second Bank of the United States in Philadelphia and Boston, took bribes from [[Joshua Bates]] of Baring Brothers & Co. bank to establish the Second National Bank of the United States in 1811 <ref> {{cite book |title=Sub Rosa |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |year=2017}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Thomas Handasyd Perkins]] Haitian slave trader up to Slave Revolt, opium dealer, owned Perkins & Co. ran by his Forbes nephews, Sold company to Russell & Co. which kept John Murray Forbes employed running the opium empire, sold lot in New Haven for William Russell to build the crypt for Skull & Bones on, hired Charles Bulfinch to build Bunker Hill monument and several properties in Boston connected by tunnels, was bribed by Joshua Bates of Baring Brothers & Co. to establish the Second Bank of the United States in 1811, director of bank in Boston.. |

|||

*Stephen White (1787-1841) head of the National Republican Party (Whig Party) for Massachusetts, Paid for the East India Marine Hall and incorporated the museum know today as [[Peabody Essex Museum]], banker for Daniel Webster, brother-in-law to Joseph Story, murdered Captain Joseph White, planned assassination of President William Harrison with Webster and Henry Clay, bribed in 1811 by Joshua Bates of Baring Brothers & Co. to establish Second Bank of the United States, and director in the Second Bank of the United States, established [[East Boston]]. <ref> {{cite book |title=Death of an Empire |author=Robert Booth |publisher= St. Martins Press |year=2011}}</ref><ref> {{cite book |title=Sub Rosa |author=Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin |publisher=Salem House Press |date=2017}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Joseph Dixon]] (1799–1869) Inventor of the SLR, high temperature crucibles, the Dixon-Ticonderoga Pencil, and anti-counterfeiting methods. |

|||

* [[Mary Tileston Hemenway]] (1820 – 1894) Sponsor of the [[Hemenway Southwestern Archaeological Expedition]]. |

|||

* [[Harriet Lawrence Hemenway]] (1858–1960) Founder of [[Massachusetts Audubon Society]]. |

|||

* [[Joseph Horace Eaton]] (1815–1896), artist and military officer |

* [[Joseph Horace Eaton]] (1815–1896), artist and military officer |

||

* [[Benjamin Crowninshield]] (December 27, 1772 – February 3, 1851) Congressman from Massachusetts, Secretary of the Navy, received bribes from Joshua Bates from Baring Brothers Bank to establish the Second Bank of the United States in 1811, director of Second Bank of the United States Boston. |

|||

* [[Ephraim Emerton]] (1851–1935), medievalist historian and Harvard chair |

* [[Ephraim Emerton]] (1851–1935), medievalist historian and Harvard chair |

||

* [[John Endecott]] (1588–1665), governor |

* [[John Endecott]] (1588–1665), governor |

||

| Line 458: | Line 518: | ||

* [[Dudley Leavitt (minister)|Dudley Leavitt]] (1720–1762), early Harvard-educated Congregational minister,<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ALQsQX07_Z4C&pg=RA2-PA735&lpg=RA2-PA735&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+stratham&source=web&ots=Wj-3l7LaEt&sig=3KpIFUivHnYEx1dl-tUe5lnMKkw&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result |title=The Native Ministry of New Hampshire, Nathan Franklin Carter, Rumford Printing Co., Concord, N.H., 1906 |publisher=Books.google.com |date=1987-04-01 |accessdate=2012-11-10}}</ref> [[New Hampshire]] native, married to Mary Pickering;<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DHcsAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA171&lpg=PA171&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+pickering&source=web&ots=-osJtVrCjH&sig=bgqzmDaDs5Yj5Rs8ZdfG5NNyYy8&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result |title=The Life of Timothy Pickering, Vol. II, Octavius Pickering, Charles Wentworth Upham, Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1873 |publisher=Books.google.com |accessdate=2012-11-10}}</ref> Leavitt Street named for him; minister of a splinter church of Salem's First Church, referred to after his death as "the Church of which the Rev. Mr. Dudley Leavitt was late Pastor"<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Co8SAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+SALEM&source=web&ots=-yZW70oWTp&sig=PD0SfVURYRDGOTQ6IUvQ6gxpXcY&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result|title=A Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle, Salem, Mass., 1854-5|publisher=}}</ref> |

* [[Dudley Leavitt (minister)|Dudley Leavitt]] (1720–1762), early Harvard-educated Congregational minister,<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ALQsQX07_Z4C&pg=RA2-PA735&lpg=RA2-PA735&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+stratham&source=web&ots=Wj-3l7LaEt&sig=3KpIFUivHnYEx1dl-tUe5lnMKkw&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result |title=The Native Ministry of New Hampshire, Nathan Franklin Carter, Rumford Printing Co., Concord, N.H., 1906 |publisher=Books.google.com |date=1987-04-01 |accessdate=2012-11-10}}</ref> [[New Hampshire]] native, married to Mary Pickering;<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DHcsAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA171&lpg=PA171&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+pickering&source=web&ots=-osJtVrCjH&sig=bgqzmDaDs5Yj5Rs8ZdfG5NNyYy8&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result |title=The Life of Timothy Pickering, Vol. II, Octavius Pickering, Charles Wentworth Upham, Little, Brown & Co., Boston, 1873 |publisher=Books.google.com |accessdate=2012-11-10}}</ref> Leavitt Street named for him; minister of a splinter church of Salem's First Church, referred to after his death as "the Church of which the Rev. Mr. Dudley Leavitt was late Pastor"<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Co8SAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA8&lpg=PA8&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+SALEM&source=web&ots=-yZW70oWTp&sig=PD0SfVURYRDGOTQ6IUvQ6gxpXcY&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result|title=A Memorial of the Old and New Tabernacle, Salem, Mass., 1854-5|publisher=}}</ref> |

||

* [[Mary Lou Lord]], singer-songwriter; grew up in Salem |

* [[Mary Lou Lord]], singer-songwriter; grew up in Salem |

||

* [[Samuel McIntire]] (1757–1811), architect and woodcarver<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=5401630|title=THE ELIAS HASKET DERBY FEDERAL CARVED MAHOGANY SIDE CHAIR|author=Christie?s|work=christies.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://antiquesandartireland.com/2011/01/antique-furniture-record/|title=ANTIQUES AND ART IRELAND - Art Auctions and Antique Auctions in Ireland|work=antiquesandartireland.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/sama/planyourvisit/upload/McTrail.pdf |format=PDF |publisher= [[National Park Service]]|title= |

* [[Samuel McIntire]] (1757–1811), architect and woodcarver<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.christies.com/LotFinder/lot_details.aspx?intObjectID=5401630|title=THE ELIAS HASKET DERBY FEDERAL CARVED MAHOGANY SIDE CHAIR|author=Christie?s|work=christies.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://antiquesandartireland.com/2011/01/antique-furniture-record/|title=ANTIQUES AND ART IRELAND - Art Auctions and Antique Auctions in Ireland|work=antiquesandartireland.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/sama/planyourvisit/upload/McTrail.pdf |format=PDF |publisher= [[National Park Service]]|title= Architecture Walking Trail in the Samuel McIntire Historic District}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pem.org/sites/mcintire/|title=PEM - Samuel McIntire: Carving an American Style Microsite|work=pem.org}}</ref> |

||

* [[Rob Oppenheim]], professional golfer |

* [[Rob Oppenheim]], professional golfer |

||

* [[Daniel Webster]] Black Dan, Great Orator, Director of the Second Bank of the United States Boston, Settled Ashburton-Webster treaty with the head of Baring Brothers Bank, Secretary of State to Presidents Fillmore, Tyler, and Harrison, basis for [[Sam the Eagle]] of the Muppets, Assassinated Presidents Polk, Harrison,and Taylor with Senator [[Henry Clay]]. |

|||

* [[Charles Grafton Page]] (1812–1868), electrical inventor |

* [[Charles Grafton Page]] (1812–1868), electrical inventor |

||

* [[George Swinnerton Parker]] (1866–1952), founder of [[Parker Brothers]] |

* [[George Swinnerton Parker]] (1866–1952), founder of [[Parker Brothers]] |

||

| Line 465: | Line 526: | ||

* [[Benjamin Peirce]] (1809–1880), mathematician and logician, director of [[U.S. Coast Survey]] from 1867-74 |

* [[Benjamin Peirce]] (1809–1880), mathematician and logician, director of [[U.S. Coast Survey]] from 1867-74 |

||

* Jerathmiel Peirce (1747-1827), half-owner of the [[Friendship of Salem]] and owner of the [[Peirce-Nichols House]] |

* Jerathmiel Peirce (1747-1827), half-owner of the [[Friendship of Salem]] and owner of the [[Peirce-Nichols House]] |

||

* [[Timothy Pickering]] (1745–1829), secretary of state<ref>Clarfield. ''Timothy Pickering and the American Republic'' p.246</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x24MAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA105&lpg=PA105&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+salem+death&source=web&ots=ClrSsTuN2q&sig=WpD1vO57neZYZn4kRonb2AzuFfc&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result|title=Historical Collections of the Essex Institute|publisher=}}</ref><ref name=wills2003>{{cite book |author = [[Garry Wills]] |year = 2003 |title = Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power |chapter = Before 1800 |url = |pages = 20–21 |publisher = [[Houghton Mifflin Company]] |isbn = 0-618-34398-9 |

* [[Timothy Pickering]] (1745–1829), secretary of state to Washington and Adams, aide de camp to Washington, head of Essex Junto, leader in Hartford Convention, planned to give New back to the British during the War of 1812.<ref>Clarfield. ''Timothy Pickering and the American Republic'' p.246</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x24MAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA105&lpg=PA105&dq=%22dudley+leavitt%22+salem+death&source=web&ots=ClrSsTuN2q&sig=WpD1vO57neZYZn4kRonb2AzuFfc&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result|title=Historical Collections of the Essex Institute|publisher=}}</ref><ref name=wills2003>{{cite book |author = [[Garry Wills]] |year = 2003 |title = Negro President: Jefferson and the Slave Power |chapter = Before 1800 |url = |pages = 20–21 |publisher = [[Houghton Mifflin Company]] |isbn = 0-618-34398-9 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

* [[Benjamin Pickman|Benjamin Pickman, Jr.]] (1763–1843), early Salem merchant for whom Pickman Street is named<ref>[http://www.pem.org/museum/newmanuscripts8-08.pdf Naturalization papers of Benjamin Pickman, Dudley Leavitt Pickman Papers, Phillips Library Collection, Peabody Essex Museum, pem.org/museum] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141218203340/http://www.pem.org/museum/newmanuscripts8-08.pdf |date=December 18, 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4yBOCV5-pEC&pg=PA161&lpg=PA161&dq=%22benjamin+pickman%22+bristol&source=web&ots=alojS6_ZAB&sig=cFBXvh8nv9dTpcN8Q-_dW13tW2o&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result|title=The Founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony|publisher=}}</ref> |

* [[Benjamin Pickman|Benjamin Pickman, Jr.]] (1763–1843), early Salem merchant for whom Pickman Street is named<ref>[http://www.pem.org/museum/newmanuscripts8-08.pdf Naturalization papers of Benjamin Pickman, Dudley Leavitt Pickman Papers, Phillips Library Collection, Peabody Essex Museum, pem.org/museum] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141218203340/http://www.pem.org/museum/newmanuscripts8-08.pdf |date=December 18, 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V4yBOCV5-pEC&pg=PA161&lpg=PA161&dq=%22benjamin+pickman%22+bristol&source=web&ots=alojS6_ZAB&sig=cFBXvh8nv9dTpcN8Q-_dW13tW2o&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=2&ct=result|title=The Founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony|publisher=}}</ref> |

||

| Line 477: | Line 538: | ||

* [[Steve Thomas (television)|Steve Thomas]], former host of PBS's ''This Old House'' |

* [[Steve Thomas (television)|Steve Thomas]], former host of PBS's ''This Old House'' |

||

* [[Bob Vila]], craftsman |

* [[Bob Vila]], craftsman |

||

* [[Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin]] (1972-) author and illustrator of several books including the <i>Salem Trilogy, Sub Rosa, Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City, Mr. Pelinger's House & Intergalactic Roadshow</i>, and <i>Max Teller's Amazing Adventure</i>. He is also an accomplished flute player on the Boston's North Shore. <ref>{{cite web | url=http://bostonvoyager.com/interview/meet-chris-dowgin-salem-smugglers-tour-salem/ | title=Meet Chris Dowgin of Salem Smugglers' Tour in Salem | Boston Voyager | accessed September 6th, 2017</ref><ref>An Acoustic Session with Chris Dowgin, Winthrop Cable Access TV, September 1, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBqmMHluBvM</ref><ref>Salem House Press, www.salemhousepress.com/Authors.html, accessed September 6th, 2017</ref> |

|||

* [[Thomas A. Watson]] (1854-1934), assistant to Alexander Graham Bell; his name was the first phrase ever uttered over a telephone<ref>{{Citation |last=Bruce |first=Robert V. |title=Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude |location=Boston |publisher=Little, Brown |page=181 |isbn=0-316-11251-8 }}.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.invent.org/hall_of_fame/457.html |title=Thomas A. Watson |author=National Inventors Hall of Fame |year=2010 |accessdate=14 July 2012}}</ref> |

* [[Thomas A. Watson]] (1854-1934), assistant to Alexander Graham Bell; his name was the first phrase ever uttered over a telephone<ref>{{Citation |last=Bruce |first=Robert V. |title=Alexander Graham Bell and the Conquest of Solitude |location=Boston |publisher=Little, Brown |page=181 |isbn=0-316-11251-8 }}.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.invent.org/hall_of_fame/457.html |title=Thomas A. Watson |author=National Inventors Hall of Fame |year=2010 |accessdate=14 July 2012}}</ref> |

||

* [[Jack Welch]], former chairman and CEO of [[General Electric]]; grew up in Salem and attended Salem High School |

* [[Jack Welch]], former chairman and CEO of [[General Electric]]; grew up in Salem and attended Salem High School |

||

* [[Roger Williams (theologian)|Roger Williams]] (1603–1683), theologian |

* [[Roger Williams (theologian)|Roger Williams]] (1603–1683), theologian, asked to leave Salem because he believed in separation of Church and State and that Native Americans deserved compensation for their lands. |

||

{{div col end}} |

{{div col end}} |

||

| Line 533: | Line 595: | ||

* Vickers, Daniel, and Vince Walsh. "Young men and the sea: The sociology of seafaring in eighteenth‐century Salem, Massachusetts," ''Social history'' (1999) 24#1 pp: 17-38. |

* Vickers, Daniel, and Vince Walsh. "Young men and the sea: The sociology of seafaring in eighteenth‐century Salem, Massachusetts," ''Social history'' (1999) 24#1 pp: 17-38. |

||

* Wagner, E.J., [http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/A-Murder-in-Salem.html "A Murder in Salem"], ''[[Smithsonian (magazine)|Smithsonian]]'' magazine, November 2010 |

* Wagner, E.J., [http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/A-Murder-in-Salem.html "A Murder in Salem"], ''[[Smithsonian (magazine)|Smithsonian]]'' magazine, November 2010 |

||

*Dowgin, Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin [https://books.google.com/books?id=97xglLJM8WcC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false "Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City"], 1st edition, Salem : Salem House Press, 2012. {{ISBN|978-0983666554}} |

|||

*Dowgin, Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin "Sub Rosa", 1st Edition, Salem : Salem House Press, 2017 {{ISBN|9780986261022}} |

|||

*Dowgin, Christopher Jon Luke Dowgin [https://books.google.com/books?id=jIjWw7jiFIsC&printsec=frontcover&dq=a+walk+through+salem&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjsiaq025LWAhXHNSYKHaoqAzIQ6AEIKDAA#v=onepage&q=a%20walk%20through%20salem&f=false "A Walk Through Salem"] 1st Edition, Salem : Norge Forge Press, 2009 {{ISBN|9780615340302}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

Revision as of 09:06, 7 September 2017

Salem, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Witch House | |

| Nickname(s): The Witch City, The City of Witches | |

| Motto: Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum (Latin: To the farthest port of the rich Indies) | |

Location in Essex County and the state of Massachusetts. | |

| Coordinates: 42°31′10″N 70°53′50″W / 42.51944°N 70.89722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Essex |

| Incorporated | 1629 |

| City | 1836 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council city |

| • Mayor | Kim Driscoll |

| Area | |

| • Total | 18.1 sq mi (46.8 km2) |

| • Land | 8.1 sq mi (21.0 km2) |

| • Water | 10.0 sq mi (25.8 km2) |

| Elevation | 26 ft (8 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 41,340 |

| • Estimate (2016)[1] | 43,132 |

| • Density | 2,300/sq mi (880/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| Area code | 351 / 978 |

| FIPS code | 25-59105 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0614337 |

| Website | www |

Salem is a coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, in the United States, located on Massachusetts' North Shore. It is a New England bedrock of history and is considered one of the most significant seaports in Puritan American history.

The city's reported population was 41,340 at the 2010 census.[2] Salem and Lawrence are the county seats of Essex County, though the county government was abolished in 1999.[3]

The city is home to the House of Seven Gables, Salem State University, the Salem Willows Park, Forest River Park, Federal Street District, Charter Street Historic District, and the Peabody Essex Museum.[4][5][6][7] Salem is a residential and tourist area which includes the neighborhoods of Salem Neck, Downtown Salem District,[8] The Point, South Salem and North Salem, Witchcraft Heights, Pickering Wharf, and the McIntire Historic District[9] (named after Salem's famous architect and carver Samuel McIntire).[10][11]

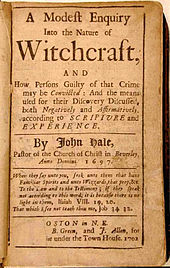

Much of the city's cultural identity reflects its role as the location of the infamous Salem witch trials of 1692, as featured in Arthur Miller's The Crucible. Police cars are adorned with witch logos, a local public school is known as the Witchcraft Heights Elementary School, the Salem High School athletic teams are named the Witches, and Gallows Hill is currently used as a playing field for various sports, originally believed to be the site of numerous public hangings. Tourists know Salem as a mix of important historical sites and a vibrant downtown that has more than 60 restaurants, cafes, and coffee shops.[12] In 2012, the Retailers Association of Massachusetts chose Salem for their inaugural "Best Shopping District" award.[13]

President Barack Obama signed executive order HR1339 on January 10, 2013, designating Salem as the birthplace of the U.S. National Guard.[14][15][16][17]

More than one million tourists from all around the world visit Salem annually, bringing in at least $100 million in tourism spending each year.[18] More than 250,000 visited Salem over Halloween weekend in 2016.[19][20][21][22][23]

History

Salem is located at the mouth of the Naumkeag river at the site of an ancient American Indian village and trading center. It was first settled by Europeans in 1626, when a company of fishermen[24] arrived from Cape Ann, led by Roger Conant. Conant's leadership provided the stability to survive the first two years, but he was replaced by John Endecott, one of the new arrivals, by order of the Massachusetts Bay Company. Conant graciously stepped aside and was granted 200 acres (0.81 km2) of land in compensation. These "New Planters" and the "Old Planters"[24][25] agreed to cooperate, in large part due to the diplomacy of Conant and Endecott. In recognition of this peaceful transition to the new government, the name of the settlement was changed to Salem, a hellenized form of the word for "peace" in Hebrew (שלום, shalom) which is mentioned many times in the Bible and associated with Jerusalem.[26][27]

In 1628, Endecott ordered that the Great ("Governor's") House be moved from Cape Ann, reassembling it on what is now Washington Street north of Church Street.[28] When Higginson arrived in Salem, he wrote that "we found a faire house newly built for the Governor" which was remarkable for being two stories high.[29] A year later, the Massachusetts Bay Charter was issued creating the Massachusetts Bay Colony with Matthew Craddock as its governor in London and Endecott as its governor in the colony.[30] John Winthrop was elected Governor in late 1629, and arrived with the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, beginning the Great Migration.[citation needed]

In 1639, Endecott's was one of the signatures on the building contract for enlarging the meeting house in Town House Square for the First Church in Salem. This document remains part of the town records at City Hall. He was active in the affairs of the town throughout his life. Samuel Skelton was the first pastor of the First Church of Salem, which is the original Puritan church in North America.[31][32] Endecott already had a close relationship with Skelton, having been converted by him, and Endecott considered him as his spiritual father.[33][34]

Roger Conant died in 1679 at the age of 87; a large statue commemorating him stands overlooking Salem Common.

Salem originally included much of the North Shore, including Marblehead. Most of the accused in the Salem witch trials lived in nearby "Salem Village", now known as Danvers, although a few lived on the outskirts of Salem. Salem Village also included Peabody and parts of present-day Beverly. Middleton, Topsfield, Wenham, and Manchester-by-the-Sea were once parts of Salem.

Puritans had come to Massachusetts to obtain religious freedom for themselves, but had no particular interest in establishing a haven for other faiths. The laws were harsh, with punishments that included fines, deprivation of property, banishment, or imprisonment.

One of the most widely known aspects of Salem is its history of witchcraft allegations, which in many popular accounts started with Abigail Williams, Betty Parris, and their friends playing with a Venus glass (mirror) and egg. Salem is also significant in legal history as the site of the Dorthy Talbye trial, where a mentally ill woman was hanged for murdering her daughter because Massachusetts made no distinction at the time between insanity and criminal behavior.[35]

William Hathorne was a prosperous businessman in early Salem and became one of its leading citizens of the early colonial period. He led troops to victory in King Philip's War, served as a magistrate on the highest court, and was chosen as the first speaker of the House of Deputies. He was a zealous advocate of the personal rights of freemen against royal emissaries and agents.[36][37] His son Judge John Hathorne came to prominence in the late 17th century, when people generally believed witchcraft to be real. Nothing caused more fear in the Puritan community than people who appeared to be possessed by demons, and witchcraft was a serious felony. Judge Hathorne is the best-known of the witch trial judges, and he became known as the "Hanging Judge" for sentencing witches to death.[38][39]

Salem and the Revolutionary War

On February 26, 1775, patriots raised the drawbridge at the North River, preventing British Colonel Alexander Leslie and his 300 troops of the 64th Regiment of Foot from seizing stores and ammunition hidden in North Salem. A few months later, in May 1775, a group of prominent merchants with ties to Salem, including Francis Cabot, William Pynchon, Thomas Barnard, E. A. Holyoke and William Pickman, felt the need to publish a statement retracting what some interpreted as Loyalist leanings and to profess their dedication to the Colonial cause.[40]

During the American Revolution, the town became a center for privateering. Although the documentation is incomplete, about 1,700 Letters of Marque, issued on a per-voyage basis, were granted during Revolution. Nearly 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers, and are credited with capturing or destroying about 600 British ships.[41] During the War of 1812, privateering resumed.

War of 1812 and the Essex Junto

In the winter of 1803-1804, a group of Federalist congressmen plotted to establish a "Northern Confederacy" consisting of New Jersey, New York, New England, and Canada, to be established with the support of Britain, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton. When traction was not found with the Adams and Hamilton the conspirators turned to Vice President Aaron Burr. With Burr on trial for Burr Conspiracy they would loose the support of New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. In Massachusetts the scheme started in Ipswich but quickly moved to Salem by the Essex Junto headed by Timothy Pickering who had served for Washington and Adams as Secretary of State. Along with Daniel Webster, George Cabot, William Prescott Jr., and Nathan Dane Pickering made loud threats that were noticed by Samuel Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Joseph Story in their various letters. During the War of 1812 Massachusetts pulled all military and financial support from the war and built their own standing forces with the threat of siding with the British who already took over what was then territory of Massachusetts, Maine. In Salem they re-outfitted the old hill fort and rename it Fort Pickering in preparation for the defense of the British once they ventured south of Maine. Webster, Pickering, Prescott, and Cabot headed south to Hartford Connecticut for a convention with threats of secession. The Hartford Convention ended up to be a comedy of errors for in Ghent the treaty was signed that ended the War. Also by the time they arrived in Washington D.C. news had arrived that Jackson and Lafitte had defeated Wellington's army in New Orleans. This could of been a serious wound to the new country, but President Monroe did a tour of New England in 1817 to heal the wounds of the Hartford Convention as the Federalist Party dissolved, for a little while later reforming as the Whig Party, but for a short time Monroe succeeded in unifying the country into a one party system and removed the specter of the collapse of the country.[42][43]

Trade with the Pacific and Africa

Following the American Revolution, many ships used as privateers were too large for short voyages in the coasting trade, and their owners determined to open new avenues of trade to distant countries. The young men of the town, fresh from service on the armed ships of Salem, were eager to embark in such ventures. Captain Nathaniel Silsbee, his first mate Charles Derby, and second mate Richard J. Cleveland were not yet twenty years old when they set sail on a nineteen-month voyage that was perhaps the first from the newly independent America to the East Indies. In 1795, Captain Jonathan Carnes set sail for Sumatra in the Malay Archipelago on his secret voyage for pepper; nothing was heard from him until eighteen months later, when he entered with a cargo of pepper in bulk, the first to be so imported into the country, and which sold at the extraordinary profit of seven hundred per cent.[44] The Empress of China, formerly a privateer, was refitted as the first American ship to sail from New York to China. By 1790, Salem had become the sixth largest city in the country, and a world-famous seaport—particularly in the China Trade, along with exporting codfish to Europe and the West Indies, importing sugar and molasses from the West Indies, tea from China, and products depicted on the city seal from the East Indies – in particular Sumatran pepper. Salem ships also visited Africa – Zanzibar in particular, Russia, Japan, and Australia.

The neutrality of the United States was tested during the Napoleonic Wars. After the Chesapeake–Leopard affair, President Thomas Jefferson was faced with a decision to make regarding the situation at hand. In the end, he chose an economic option: the Embargo Act of 1807. Jefferson essentially closed all the ports overnight, putting a damper on the seaport town of Salem. The embargo of 1807 was the starting point on the path to the War of 1812 with Great Britain. Both Great Britain and France imposed trade restrictions in order to weaken each other's economies. This also had the effect of disrupting American trade and testing the United States' neutrality. As time went on, harassment of American ships by the British Navy increased. This included impressment and seizures of American men and goods.[45]

The Salem–India Story by Vanita Shastri narrates the adventures of the Salem seamen who connected the far corners of the globe through trade. This period (1788–1845) marks the beginning of U.S. international relations, long before the 21st century wave of globalization. It reveals the global trade connections that Salem had established with faraway lands, which were a source of livelihood and prosperity for many. Charles Endicott, master of Salem merchantman Friendship, returned in 1831 to report Sumatran natives had plundered his ship, murdering the first officer and two crewmen. Following public outcry, President Andrew Jackson ordered the Potomac on the First Sumatran Expedition, which departed New York City on August 19, 1831. This also led to the mission of diplomatist Edmund Roberts, who negotiated a treaty with Said bin Sultan, Sultan of Muscat and Oman on September 21, 1833.[46] In 1837, the sultan moved his main place of residence to Zanzibar and welcomed Salem citizen Richard Waters as a United States consul of the early years.[45]

Legacy of the East Indies and Old China Trade

The Old China Trade left a significant mark in two historic districts, Chestnut Street District, part of the Samuel McIntire Historic District containing 407 buildings, and the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, consisting of 12 historic structures and about 9 acres (36,000 m²) of land along the waterfront in Salem. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary merchants in Salem. Derby was also the owner of the Grand Turk, the first New England vessel to trade directly with China and second to sail from America after the Empress of China. Thomas H. Perkins was his supercargo and established strong ties with the Chinese and garnered the Forbes fortune through his illegal opium sales.

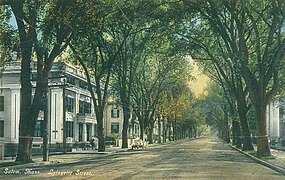

Salem was incorporated as a city on March 23, 1836,[47] and adopted a city seal in 1839 with the motto "Divitis Indiae usque ad ultimum sinum", Latin for "To the rich East Indies until the last lap." Nathaniel Hawthorne was overseer of Salem's port from 1846 until 1849. He worked in the U.S. Customs House across the street from the port[48] near Pickering Wharf, his setting for the beginning of The Scarlet Letter. In 1858, an amusement park was established at Juniper Point, a peninsula jutting into the harbor. Prosperity left the city with a wealth of fine architecture, including Federal-style mansions designed by one of America's first architects, Samuel McIntire, for whom the city's largest historic district is named. These homes and mansions now comprise the greatest concentrations of notable pre-1900 domestic structures in the United States.

Shipping declined throughout the 19th century. Salem and its silting harbor were increasingly eclipsed by nearby Boston and New York City. Consequently, the city turned to manufacturing. Industries included tanneries, shoe factories, and the Naumkeag Steam Cotton Company. More than 400 homes were destroyed in the Great Salem Fire of 1914, leaving 3,500 families homeless from a blaze that began in the Korn Leather Factory at 57 Boston Street. The historic concentration of Federal architecture on Chestnut Street were spared from destruction by fire, in which they still exist to this day. A memorial plaque currently exists where the Korn Leather Factory once stood, on what is now a Walgreens store.

Derby Tunnels

In 1801, Elias Hasket Derby, Jr. extended the tunnel system in Salem, Massachusetts, in response to Thomas Jefferson's new custom duties.[49] Jefferson had ordered the local militias to help collect these duties, but in Salem, Derby had hired the local militia (later the United States' first National Guard unit), the 101st Engineer Battalion, to dig the tunnels and hide the spoils in five ponds in the local common.

This extension was funded by the Salem Common Improvement Fund, whose members included Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Crowninshield, Congressman Jacob Crowninshield, Senator Nathaniel Silsbee, lawyer Daniel Webster, Senator William Gray, Senator Benjamin Pickman, Jr., and the London banker and JPMorgan Chase founder George Peabody.

Salem's head of customs, Joseph Hiller, was also a member, as was Benjamin Crowninshield, head of customs for Marblehead, Massachusetts. Presidents George Washington, James Monroe, and John Quincy Adams might have walked in the tunnels as well. At a minimum, they visited many homes that were connected to the tunnels, and John Quincy Adams dedicated the East India Marine Hall, which had four sub-basements and was connected to the tunnels.[50] The East India Marine Society Museum had many locations in town that were connected to the tunnels. The society became the Peabody Academy of Science with the support of Joseph Peabody, and the tunnels became part of the Peabody Essex Museum after it merged with the Essex Institute in 1992.

The Essex Institute — established by Edward Augustus Holyoke, founder of the The New England Journal of Medicine — was also connected to the tunnels.

The tunnels were used by Charles Lenox Remond to move runaway slaves along the Underground Railroad. They were also used to transport illicit liquor during the Prohibition Era.

The tunnels extended three miles from the town's wharfs to an underground train station built by the superintendent of the Eastern Railroad, John Kinsman. Along the way, they connected several homes, stores, and banks. Two large brick homes were built at fixed distances to conceal the purchases of bricks needed for the tunnel. Many large churches were made out of bricks for the same reason.[51]

Samuel McIntire fashioned the Federal style of architecture after Charles Bulfinch, who would become the architect of the Capitol. In both of these men's designs, homes had exterior chimneys that connected to the tunnels through watertight fireplace arches.

These arches and their flues provided not only a dry entrance to the homes but also a draw system up through the chimneys for the tunnels. Bulfinch connected his Looby Asylum, Essex Bank Building, and Old Town Hall to the tunnels in Salem. He would also build tunnels from the State House in Boston and the National Capitol.[52]

Smuggling tunnels are common in most New England seaports. These towns relied on imports and had built tunnels in response to Jefferson's new custom duties. In places like New Londondery, New Hampshire, Marblehead, Massachusetts, and Salem, the heads of customs turned a blind eye to the smugglers. Joseph Hiller was the head of customs in Salem. He was the Master Mason of the Essex Lodge and a conspirator in the Salem Common Improvement Fund.[53] The fund was a subterfuge to underwrite a massive tunnel spanning three miles, used to avoid paying Jefferson's new custom duties in 1801. Another member of the fund was Secretary of the Navy Benjamin Crowninshield, who was head of customs in Marbelhead. In fact the Custom House in Salem was built atop the basement of his father's house, with the old tunnels still leading to it. (Crowninshield's father, George Crowninshield, started the Boston Brahmin Crowninshield family.) Benjamin Crowninshield's home was also connected. President James Monroe visited his home plus many others in town that were connected to the tunnel. [54][55] George Washington celebrated his birthday in Assembly Hall in town and slept in the Joshua Ward House. Both buildings were connected to the tunnels.

John Quincy Adams lectured at the Salem Lyceum, visited the banker Joseph Peabody, dedicated the East India Marine Hall, and was entertained at Hamilton Hall. All of those buildings were connected to the tunnels.

Others who used the tunnels included:

- The murderer of Joseph White in 1830.

- The Parker brothers, who inherited the wealth left to them by their father, Colonel William Parker, who utilized those tunnels extensively.

- Charles Lenox Remond used the tunnels to transport runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad. The tunnels even connected the sea to an Underground Railroad station.

The tunnels were extended by Elias Hasket Derby, Jr. His father, Elias Hasket Derby, Sr., was America's first millionaire and the most successful owner of a fleet of privateers during the American Revolutionary War.

The Architect of the Capitol Charles Bulfinch built the Looby Asylum, Old Town Hall, and the Essex Bank Building in Salem, which all connected to the tunnels. Old Town Hall was built on the site of Elias Hasket Derby's last mansion in town. This was the money pit that spurred his son to dig tunnels to support it. After it was demolished Bulfinch had built Old Town Hall on its location, extending the tunnel entrances to it.

One of the oldest elite societies in America, the Salem Marine Society, had tunnels leading into their building where the Hawthorne Hotel is now. They still have their club house on top of the building. They received the deed from the opium dealer Thomas Handasyd Perkins. Their sister organization, the Salem East India Marine Society (founded by Jonathan and John Hodges), created a museum which would eventually merge with the Essex Institute (which was founded by Edward Augustus Holyoke). Both museums have been connected to the tunnels for over 200 years.

The Hodges' home actually connected to Elias Hasket Derby's home. The East India Marine Society Museum would be renamed the Peabody Academy of Science, after Joseph Peabody found they were near destitution. In 1992, the two museums merged to create the Peabody Essex Museum.

In later years the tunnels were used during Prohibition. Bunghole Liquors, which received the second liquor license in town after Prohibition, has a basement that was a speakeasy hidden under a funeral home, and that basement is attached to the tunnels.[56]

Inventions

Many inventors lived in Salem. Moses Farmer was the first to light his home by electricity and sold his lightbulb to Thomas Edison. Edison also used his arc lighting in his demonstrations. Farmer provided Tesla with his lightbulbs for Westinghouse after Edison refused to sell them his to light the Columbian Exposition World Fair of 1893. Farmer would die at the fair. Charles Grafton Page made an electromagnet that could lift 1,000 pounds, electric train, an early telegraph, and worked in the US patent office. He was a precursor to what would befall Tesla for his laboratory had burned down during the Civil War and the section of the Smithsonian which housed his magnet also burned at a later date. Joseph Dixon the inventor of high temperature graphite crucibles, the Single Reflex Lens, and the Dixon-Ticonderoga #2 pencil lived in Salem. Packard Electric were making electric cars in the nineteenth century up to the 1914 fire which destroyed their factory. Alexander Graham Bell invented the phone in Salem and held the first public demonstration at the Salem Lyceum Hall. Also Nicola Tesla would create a power plant for Pequot Mills. He was in the area after Mark Twain introduced him to John Hammond Sr.. Tesla would give his son, John Hammond Jr. the patents for remote control which Hammond used to develop guided missiles and boats for the military during WWII. Tesla would conduct tests on ESP at Hammond Castle using a Faraday Cage to prove ESP did not transmit through electromagnetic waves, for a psychic received a message from a woman in the cage a few miles away. It was John Hammond Sr. who helped destroy Tesla's plans for free wireless electricity since he just invested heavily in a copper mine that was going to create electrical lines for transmission. Also Elihu Thomson had his Thomson-Houston Electric Company in the bordering town of Lynn and lived in the other border town Swampscott. This company will be merged with Edison Electric Company to make General Electric. Many of these Salem inventors' inventions are still displayed in the Smithsonian in the electricity display room.

Air Station and the National Guard

Coast Guard Air Station Salem was established on February 15, 1935 when the U.S. Coast Guard established a new seaplane facility in Salem because there was no space to expand the Gloucester Air Station at Ten Pound Island. Coast Guard Air Station Salem was located on Winter Island, an extension of Salem Neck which juts out into Salem Harbor. Search and rescue, hunting for derelicts, and medical evacuations were the station's primary areas of responsibility. During its first year of operation, Salem crews performed 26 medical evacuations. They flew in all kinds of weather, and the radio direction capabilities of the aircraft were of significant value in locating vessels in distress.

During World War II (1939–45), air crews from Salem flew neutrality patrols along the coast, and the Air Station roster grew to 37 aircraft. Anti-submarine patrols were flown on a regular basis. In October 1944, Air Station Salem was officially designated as the first Air-Sea Rescue station on the eastern seaboard. The Martin PBM Mariner, a hold-over from the war, became the primary rescue aircraft. In the mid-1950s, helicopters came, as did Grumman HU-16 Albatross amphibious flying boats (UFs).

The air station's missions included search and rescue, law enforcement, counting migratory waterfowl for the U.S. Biological Survey, and assisting icebound islands by delivering provisions.[57][58]

The station's surviving facilities are part of Salem's Winter Island Marine Park. Salem Harbor was deep enough to host a seadrome with three sea lanes, offering a variety of take-off headings irrespective of wind direction unless there was a strong steady wind from the east. This produced large waves that swept into the mouth of the harbor, making water operations difficult. When the seadrome was too rough, returning amphibian aircraft would use Naval Auxiliary Air Facility Beverly. Salem Air Station moved to Cape Cod in 1970.

In 2011, the City of Salem finalized plans for the 30-acre (12 ha) Winter Island Park[59] and squared off against residents who are against bringing two power generating windmills to the tip of Winter Island.[60] The Renewable Energy Task Force, along with Energy and Sustainability Manager, Paul Marquis, have recommended the construction of a 1.5-megawatt power turbine at the tip of Winter Island,[61] which is the furthest point from residences and where the winds are the strongest.[62]

The nearly 30-acre park has been open to the public since the early 1970s. In 2011, a master plan was developed with help from the planning and design firm, Cecil Group of Boston and Bioengineering Group of Salem. The City of Salem paid $45,000 in federal money.[63] In the long term, the projected cost to rehabilitate just the barracks was $1.5 million. But in the short term, there are multiple lower-cost items, like a proposed $15,000 kayak dock or $50,000 to relocate and improve the bathhouse. This is a very important project since Fort Pickering guarded Salem Harbor as far back as the 17th century.[64]

Designation as National Guard Birthplace

In 1637, the first muster was held on Salem Common, where for the first time a regiment of militia drilled for the common defense of a multi-community area,[65] thus laying the foundation for what became the Army National Guard. In 1637, the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony ordered the organization of the Colony's militia companies into the North, South and East Regiments. The colonists adopted the English militia system, which obligated all males between the ages of 16 and 60 to possess arms and participate in the defense of the community.[15][16]

On August 19, 2010, Governor of Massachusetts Deval Patrick signed HB1145, "An Act Designating the City of Salem as the Birthplace of the National Guard."[66] This as later approved by the U.S. House of Representatives in March 2012,[67] and was signed into law by President Barack Obama on January 10, 2013.[68] This executive order designated the City of Salem, Mass., as the birthplace of the U.S. National Guard.[69]

Each April, the Second Corps of Cadets gather in front of St. Peter's Episcopal Church, where the body of their founder, Stephen Abbott, is buried. They lay a wreath, play "Taps" and fire a 21-gun salute. In another annual commemoration, soldiers gather at Old Salem Armory to honor soldiers who were killed in the Battles of Lexington and Concord. On April 14, 2012, Salem celebrated the 375th anniversary of the first muster on Salem Common, with more than 1,000 troops taking part in ceremonies and a parade.[70]

World record for Federal furniture

In 2011, a mahogany side chair with carving done by Samuel McIntire sold at auction for $662,500.[71] The price set a world record for Federal furniture. McIntire was one of the first architects in the United States, and his work represents a prime example of early Federal-style architecture. Elias Hasket Derby, Salem's wealthiest merchant and thought to be America's first millionaire, and his wife, Elizabeth Crowninshield, purchased the set of eight chairs from McIntire.[72]

The Samuel McIntire Historic District represents the greatest concentration of 17th and 18th century domestic structures anywhere in America.[citation needed] It includes McIntyre commissions such as the Peirce-Nichols House and Hamilton Hall. The Witch House or Jonathan Corwin House (circa 1642) is also located in the district. Samuel McIntyre's house and workshop were located at 31 Summer Street in what is now the Samuel McIntire Historic District.

Film, literature, and television in Salem

- The 2015 single "Spirit of Salem" by Majungas was inspired by Salem's October tourist attraction—Haunted Happenings.[73]

- Salem Secret Underground:The History of the Tunnels in the City goes over a grand conspiracy engineered by the son of America's first millionaire, and paid for by many of the country's most influential politicians during the Adams administration, that involved using three miles of tunnels to avoid paying duties on imports.[further explanation needed] Dowgin, Christopher Jon Luke (2009). Salem Secret Underground: The History of the Tunnels in the City. Salem, MA: Salem House Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-9836665-5-4.

- In June 1970, Bewitched filmed on location in Salem.

- The Europeans, an Academy Award-nominated adaptation of the Henry James novel, starring Lee Remick, filmed in 1978 and was released in 1979.

- Three Sovereigns for Sarah, PBS drama starring Vanessa Redgrave, 1985

- Hocus Pocus, Disney's Halloween comedy-drama film starring Bette Midler, Sarah Jessica Parker, and Kathy Najimy. The daytime scenes were filmed in Salem while the nighttime scenes were filmed at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank, California.

- The Travel Channel, "Places of Mystery: Witch City," 2000; "Ghost Adventures," 2010

- In 2007, PBS's aired a documentary titled "Hand of God" regarding the sexual abuse and cover up of a Salem priest serving at St. James Church in the 1960s.

- In 2008, scenes from the film Bride Wars were filmed here.[74]

- An episode of the TLC series What Not to Wear was filmed in Salem in 2009.

- The 2012 Rob Zombie movie The Lords of Salem was set and filmed in Salem.[75][76]

- Some interior and street scenes for 2013's American Hustle were filmed on Federal St. in Salem, outside the Essex Superior Court House and Old Granite Courthouse.[77][78][79]

- The WGN America Salem (TV series) is set in the city during the Salem Witch Trials.

- Historic images of Salem

-

One of Many Sealed Tunnel Entrances in Salem

-

Salem Depot, 1910

-

Peabody House, c. 1905

-

Salem Harbor in 1907

-

Lafayette Street in 1910

-

Naumkeag Mills, c. 1910

-

Roger Williams House (The Witch House) c. 1910

-

Sampler (needlework) made in Salem in 1791. Art Institute of Chicago textile collection.

-

Pickering House, c. 1905

-

Essex Street, c. 1920

-

Town House Square, 1891

Geography

Salem is located at 42°31′1″N 70°53′55″W / 42.51694°N 70.89861°W (42.516845, -70.898503).[80] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 18.1 square miles (47 km2), of which 8.1 square miles (21 km2) is land and 9.9 square miles (26 km2), or 55.09%, is water. Salem lies on Massachusetts Bay between Salem Harbor, which divides the city from much of neighboring Marblehead to the southeast, and Beverly Harbor, which divides the city from Beverly along with the Danvers River, which feeds into the harbor. Between the two harbors lies Salem Neck and Winter Island, which are divided from each other by Cat Cove, Smith Pool (located between the two land causeways to Winter Island), and Juniper Cove. The city is further divided by Collins Cove and the inlet to the North River. The Forest River flows through the south end of town, along with Strong Water Brook, which feeds Spring Pond at the town's southwest corner. The town has several parks, as well as conservation land along the Forest River and Camp Lion, which lies east of Spring Pond.

The city is divided by its natural features into several small neighborhoods. The Salem Neck neighborhood lies northeast of downtown, and North Salem lies to the west of it, on the other side of the North River. South Salem is south of the South River, lying mostly along the banks of Salem Harbor southward. Downtown Salem lies 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Boston, 16 miles (26 km) southwest of Gloucester and Cape Ann, and 19 miles (31 km) southeast of Lawrence, the other county seat of Essex County. Salem is bordered by Beverly to the north, Danvers to the northwest, Peabody to the west, Lynn to the south, Swampscott to the southeast, and Marblehead to the southeast. The town's water rights extend along a channel into Massachusetts Bay between the water rights of Marblehead and Beverly.

Transportation

Roads

The connection between Salem and Beverly is made across the Danvers River and Beverly Harbor by three bridges, the Kernwood Bridge to the west, and a railroad bridge and the Essex Bridge, from the land between Collins Cove and the North River, to the east. The Veterans Memorial Bridge carries Massachusetts Route 1A across the river. Route 1A passes through the eastern side of the city, through South Salem towards Swampscott. For much of its length in the city, it is coextensive with Route 114, which goes north from Marblehead before merging with Route 1A, and then heading northwest from downtown towards Lawrence. Route 107 also passes through town, entering from Lynn in the southwest corner of the city before heading towards its intersection with Route 114 and terminating at Route 1A. There is no highway access within the city; the nearest highway access to Route 128 is along Route 114 in neighboring Peabody.

Rail

Salem has a station on the Newburyport/Rockport Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail. The railroad lines are also connected to a semi-abandoned portion of freight lines which lead into Peabody, and a former line into Marblehead has been converted into a bike path.

Bus

Several MBTA Bus routes pass through the city.

Airports

The nearest small airport is Beverly Municipal Airport, and the nearest national and international service can be reached at Boston's Logan International Airport.

The Salem Ferry