History of the Catholic Church in the United States: Difference between revisions

→European immigrants: Eliminating redundant section |

→Colonial era: Expanding and reorganizing |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Colonial era== |

==Colonial era== |

||

===Spanish missions=== |

|||

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States before the [[Protestant Reformation]] with the [[Spain|Spanish]] explorers and settlers in present-day [[Florida]] (1513) and the [[southwest United States|southwest]]. The first Christian worship service held in the current United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in Pensacola, FL.(St. Michael records) The influence of the [[Spanish Missions of California|Alta California missions]] (1769 and onwards) forms a lasting memorial to part of this heritage. |

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States before the [[Protestant Reformation]] with the [[Spain|Spanish]] explorers and settlers in present-day [[Florida]] (1513) and the [[southwest United States|southwest]]. The first Christian worship service held in the current United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in Pensacola, FL.(St. Michael records) The influence of the [[Spanish Missions of California|Alta California missions]] (1769 and onwards) forms a lasting memorial to part of this heritage. |

||

Until the 19th century, the Roman Catholic Church had to operate its missions under the [[Spain|Spanish]] and [[Portugal|Portuguese]] governments and military. <ref>Franzen, 362</ref> [[Junípero Serra]] founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions.<ref name="Norman111">Norman, ''The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History'' (2007), pp. 111–2</ref> These missions brought grain, cattle and a new way of living to the Indian tribes of California. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization of [[San Francisco, California|San Francisco]] in 1776 and [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] in 1781. However, by bringing Western civilization to the area, these missions and the Spanish government have been held responsible for wiping out nearly a third of the native population, primarily through disease.<ref name="King">King, ''Mission to Paradise'' (1975), p. 169</ref> |

|||

===French territories=== |

|||

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of colonies and forts in [[Detroit]], [[St. Louis]], [[Mobile]], [[Biloxi]], [[Baton Rouge]], and [[New Orleans]]. As early as 1604, the French established a site in [[Maine]] on [[Saint Croix Island]], but it was short-lived. |

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of colonies and forts in [[Detroit]], [[St. Louis]], [[Mobile]], [[Biloxi]], [[Baton Rouge]], and [[New Orleans]]. As early as 1604, the French established a site in [[Maine]] on [[Saint Croix Island]], but it was short-lived. |

||

===English colonies=== |

|||

In the English colonies, Catholicism was introduced with the settling of [[Maryland]] in 1634 |

In the English colonies, Catholicism was introduced with the settling of [[Maryland]] in 1634. Maryland was one of the few regions among the English colonies in North America that was predominantly Catholic. However, at the time of the [[American Revolution]], Catholics formed less than 1% of the population of the thirteen colonies, and only one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, [[Charles Carroll of Carrollton|Charles Carroll]], was a Catholic. |

||

The [[Maryland Toleration Act]], issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of religion (as long as it was [[Christianity|Christian]]). It has been considered a precursor to the [[First Amendment to the United States Constitution|First Amendment]]. |

|||

===Anti-Catholicism=== |

===Anti-Catholicism=== |

||

Revision as of 03:22, 30 March 2009

Colonial era

Spanish missions

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States before the Protestant Reformation with the Spanish explorers and settlers in present-day Florida (1513) and the southwest. The first Christian worship service held in the current United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in Pensacola, FL.(St. Michael records) The influence of the Alta California missions (1769 and onwards) forms a lasting memorial to part of this heritage.

Until the 19th century, the Roman Catholic Church had to operate its missions under the Spanish and Portuguese governments and military. [1] Junípero Serra founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions.[2] These missions brought grain, cattle and a new way of living to the Indian tribes of California. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization of San Francisco in 1776 and Los Angeles in 1781. However, by bringing Western civilization to the area, these missions and the Spanish government have been held responsible for wiping out nearly a third of the native population, primarily through disease.[3]

French territories

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of colonies and forts in Detroit, St. Louis, Mobile, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. As early as 1604, the French established a site in Maine on Saint Croix Island, but it was short-lived.

English colonies

In the English colonies, Catholicism was introduced with the settling of Maryland in 1634. Maryland was one of the few regions among the English colonies in North America that was predominantly Catholic. However, at the time of the American Revolution, Catholics formed less than 1% of the population of the thirteen colonies, and only one of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll, was a Catholic.

The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of religion (as long as it was Christian). It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment.

Anti-Catholicism

American Anti-Catholicism has its origins in the Reformation which developed a deep-rooted antipathy for the Roman Church as a result of its long struggle to establish its independence outside the church. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to the New World by British colonists who were predominantly Protestant, and who opposed not only the Roman Catholic Church but also the Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently Reformed.

Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia."[4] Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Another result of this was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant, that Anglicans elsewhere had shown some care in using too prominently due to their own reservations about the nature of the Church of England, and other Anglican bodies, vis-à-vis later radical reformers who were happier to use the term Protestant.

In 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil." [5].

19th century

The main source of Roman Catholics in the United States was the huge numbers of European immigrants of the 19th and early 20th centuries. These huge numbers of immigrant Catholics came from Ireland, Southern and Western Germany (Bavaria, Baden-Wurttemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate), Austria, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Substantial numbers of Catholics also came from French Canada during the mid-19th century and settled in New England. Since then, there has been cross-fertilization of the Catholic population as members of historically Catholic groups converted to various Protestant faiths, and vice-versa, with Catholics of (usually partial) English, Scottish, north German, Norwegian, or Swedish descent not uncommon.

By 1850 Roman Catholics had become the country’s largest single denomination. Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled through immigration; by the end of the decade it would reach seven million. These huge numbers of immigrant Catholics came from Ireland, Southern Germany, Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe. This influx would eventually bring increased political power for the Roman Catholic Church and a greater cultural presence, led at the same time to a growing fear of the Catholic "menace."

Parochial schools

The Catholic parochial school system developed in the early-to-mid-nineteenth century partly in response to what was seen as anti-Catholic bias in American public schools. Most states passed a constitutional amendment, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools, a possible outcome with heavy immigration from Catholic Ireland after the 1840s. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, in theory, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it were religious. However, no state school system had, by 2009, changed its laws to allow this.[6]

Plenary Councils of Baltimore

In the latter half of the 19th century, the first attempt at standardizing discipline in the American Church occurred with the convocation of the Plenary Councils of Baltimore. These councils resulted in the Baltimore Catechism and the establishment of the Catholic University of America.

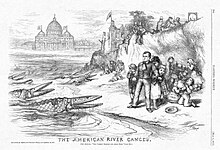

Anti-Catholicism

Some anti-immigrant and Nativism movements, like the Know Nothings and the Ku Klux Klan, have also been anti-Catholic. Indeed for most of the history of the United States, Catholics have been persecuted. It was not until the Presidency of John F. Kennedy that Catholics lived in the U.S. free of scrutiny. The Ku Klux Klan-ridden South discriminated against Catholics for their commonly Irish, Italian, Polish, or Spanish ethnicity. Those in the Protestant Midwest and North labeled Catholics as anti-American "Papists", incapable of free thought without the approval of the Pope.

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Fearing the end of time, some American Protestants who believed they were God's chosen people, went so far as to claim that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.[7]

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.[8]

This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for raising the taxes of the country[citation needed] as well as for spreading violence and disease.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Roman Catholic. Modern Roman Catholic immigrants come to the United States from the Philippines, Poland, and Latin America, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism and diversity has greatly impacted the flavor of Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses serve in both the English language and the Spanish language. This multiculturalism and diversity has greatly impacted the flavor of Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses serve the faithful in both the English language and the Spanish language. Also, when many parishes were set up in the United States, separate churches were built for parishioners from Ireland, Germany, Italy, etc. In Iowa, the development of the Archdiocese of Dubuque, the work of Bishop Loras and the building of St. Raphael's Cathedral illustrate this point.

In the later 20th century "[...] the Catholic Church in the United States became the subject of controversy due to allegations of clerical child abuse of children and adolecents, of episcopal negligence in arresting these crimes, and of numerous civil suits that cost Catholic dioceses hundreds of millions of dollars in damages."[9] Because of this, higher scrutiny and governance, as well as protective policies and diocesian investigation into seminaries have been enacted to correct these former abuses of power, and safeguard parishioners and the Church from further abuses and scandals.

References

- ^ Franzen, 362

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 111–2

- ^ King, Mission to Paradise (1975), p. 169

- ^ Ellis, John Tracy.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|American Catholicism year=ignored (help) - ^ Annotation

- ^ Bush, Jeb (March 4, 2009). NO:Choice forces educators to improve. The Atlanta Constitution-Journal.

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D. Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University

Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-838-63227-0.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 31 (help) - ^ Jimmy Akin (2001-03-01). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ Patrick W. Carey, Catholics in America. A History, Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger, 2004, p. 141

See also

Additional reading

- Fogarty, Gerald P. Commonwealth Catholicism: A History of the Catholic Church in Virginia, ISBN 978-0268022648.