Healthcare reform in the United States: Difference between revisions

→Common arguments for and against nationalized health care: mention rescission as a problem with private coverage |

|||

| Line 357: | Line 357: | ||

*[[National health insurance]] |

*[[National health insurance]] |

||

*[[Healthcare rationing in the United States]] |

*[[Healthcare rationing in the United States]] |

||

*[[Wendell Potter]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 21:18, 15 September 2009

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States |

|---|

|

|

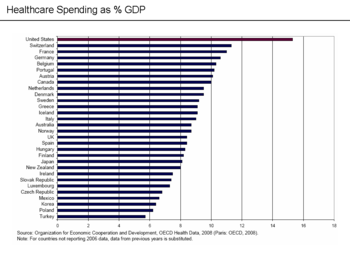

The debate over health care reform in the United States centers on questions about whether there is a fundamental right to health care, on who should have access to health care and under what circumstances, on the quality achieved for the high sums spent, and on the sustainability of expenditures that have been rising faster than the level of general inflation and the growth in the economy. Medical debt is the leading cause of personal bankruptcy in the United States.[1][2] The mixed public-private health care system in the United States is the most expensive in the world, with health care costing substantially more per person than in any other nation on Earth.[3] A greater portion of gross domestic product (GDP) is spent on health care in the U.S. than in any United Nations member state except for Tuvalu.[4] A study of international health care spending levels in the year 2000, published in the health policy journal Health Affairs, found that while the U.S. spends more on health care than other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the use of health care services in the U.S. is below the OECD median. The authors of the study concluded that the prices paid for health care services are much higher in the U.S.[5]

According to the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, the United States is the "only wealthy, industrialized nation that does not ensure that all citizens have coverage".[6] Whether a federal government-mandated system of universal health care should be implemented in the U.S. remains a hotly debated political topic, with Americans divided along party lines in their views regarding whether a new public health plan should be created and administered by the federal government.[7] Those in favor of government-guaranteed universal health care argue that the large number of uninsured Americans creates direct and hidden costs shared by all, and that extending coverage to all would lower costs and improve quality.[8] Opponents of government mandates or programs for universal health care argue that people should be free to opt out of health insurance.[9] Both sides of the political spectrum have also looked to more philosophical arguments, debating whether people have a fundamental right to have health care provided to them by their government.[10][11]

Costs

Current figures estimate that spending on health care in the U.S. is about 16% of its GDP.[12][13] In 2007, an estimated $2.26 trillion was spent on health care in the United States, or $7,439 per capita.[14] Health care costs are rising faster than wages or inflation, and the health share of GDP is expected to continue its upward trend, reaching 19.5 percent of GDP by 2017.[12] In fact, government health care spending in the United States is consistently greater, as a portion of GDP, than in Canada, Italy, the United Kingdom and Japan (countries that have predominantly public health care).[15] And an even larger portion is paid by private insurance and individuals themselves. A recent study found that medical expenditure was a significant contributing factor in 60% of personal bankruptcies in the United States. "Unless you're Warren Buffett, your family is just one serious illness away from bankruptcy...for middle-class Americans, health insurance offers little protection...," said Dr. David Himmelstein of Harvard University, who helped compile the study.[16]

The U.S. spends more on health care per capita than any other UN member nation.[4] It also spends a greater fraction of its national budget on health care than Canada, Germany, France, or Japan. In 2004, the U.S. spent $6,102 per capita on health care, 92.7% more than any other G7 country, and 19.9% more than Luxembourg, which, after the U.S., had the highest spending in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).[17] Although the U.S. Medicare coverage of prescription drugs began in 2006, most patented prescription drugs are more costly in the U.S. than in most other countries. Factors involved are the absence of government price controls, enforcement of intellectual property rights limiting the availability of generic drugs until after patent expiration, and the monopsony purchasing power seen in national single-payer systems.[citation needed] Some U.S. citizens obtain their medications, directly or indirectly, from foreign sources, to take advantage of lower prices.

The U.S. system already has substantial public components. The federal Medicare program covers nearly 45 million elderly and some people with disabilities; the federal-state Medicaid program provides coverage to the poor; the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) extends coverage to low-income families with children; Native Americans are covered both on the reservation (by tribal hospital), and in the urban setting (by hospitals maintained by the Indian Health Service) ; merchant seamen are covered by the Public Health System;[citation needed] and retired railway workers and military veterans are also covered by the government.[18]

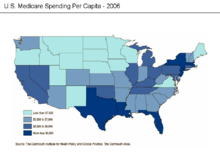

The Congressional Budget Office has argued that the Medicare program as currently structured is unsustainable without significant reform, as tax revenues dedicated to the program are not sufficient to cover its rapidly increasing expenditures. Further, the CBO also projects that "total federal Medicare and Medicaid outlays will rise from 4 percent of GDP in 2007 to 12 percent in 2050 and 19 percent in 2082—which, as a share of the economy, is roughly equivalent to the total amount that the federal government spends today. The bulk of that projected increase in health care spending reflects higher costs per beneficiary rather than an increase in the number of beneficiaries associated with an aging population."[19] The Government Accountability Office reported that the unfunded liability facing Medicare as of January 2007 was $32.1 trillion, which is the present value of the program deficits expected for the next 75 years in the absence of reform.[20] According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, spending on Medicare will grow from approximately $500 billion during 2009 to $930 billion by 2018. Without changes, the system is guaranteed “to basically break the federal budget,” President Obama said at a White House news conference July 22.[21]

Uninsured

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, people in the U.S. without health insurance coverage at some time during 2007 totaled 15.3% of the population, or 45.7 million people.[22][23] According to the Census Bureau, this number decreased slightly from 47 million in 2006 due to increased publicly sponsored coverage in addition to the fact that about 300,000 more people were covered in Massachusetts under the Massachusetts health care reform law in 2007.[24] In 2009, the Census Bureau estimated that there are 47 million Americans who do not have any health insurance at all.[25] Other studies, which complement the Census Bureau and include data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, have placed the number of uninsured for all or part of the years 2007-2008 as high as 86.7 million, about 29% of the U.S. population, or about one-in-three among those under 65 years of age.[26][27]

It is estimated that the current economic downturn and rising unemployment rate likely will have caused the number of uninsured to grow by at least 2 million in 2008.[24][26] Fareed Zakaria wrote that only 38% of small businesses provide health insurance for their employees during 2009, versus 61% in 1993, due to rising costs.[28]

During September 2009, Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL) stated that the average family pays an additional $1,000 per year in insurance premiums to cover the uninsured.[29] President Obama, in his September 9 remarks to a joint session of Congress on health care, called the cost of uninsured Americans "a hidden and growing tax."[30] The Pacific Research Institute argues that the uninsured subsidize the insured, do not drive up the cost of health care, and use fewer services than the insured.[31] A 2004 editorial in USA Today asserted that United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) data show the uninsured are unfairly billed for services at rates far higher—305% in some areas of California—than are the insured; USA Today concluded that "millions of [uninsured patients] are forced to subsidize insured patients."[32] According to the editorial:

"Many hospitals say they have to charge the uninsured high 'sticker prices' or risk violating a federal ban on charging Medicare patients more than other customers. Hospitals also must try to collect what patients owe, or they could lose Medicare reimbursement for bad debts, notes a 2003 study by the Commonwealth Fund, a health-policy-research foundation."[33]

Comparisons with other health care systems

The cost and quality of care in the United States are frequently the two major issues of discussion. While cost comparisons are relatively easy, the reasons for higher costs in the U.S. and quality measures are frequently subject to debate. The U.S. pays twice as much yet lags other wealthy nations in such measures as infant mortality and life expectancy, which are among the most widely collected, hence useful, international comparative statistics. For 2006-2010, the U.S. life expectancy will lag 38th in the world, after most rich nations, lagging last of the G5 (Japan, France, Germany, U.K., U.S.) and just after Chile (35th) and Cuba (37th).[34]

In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked the U.S. health care system 37th in overall performance, right next to Slovenia, and 72nd by overall level of health (among 191 member nations included in the study).[3][35] The WHO study has been criticized by the free market advocate David Gratzer because "fairness in financial contribution" was used as an assessment factor, marking down countries with high per-capita private or fee-paying health treatment.[36] One study found that there was little correlation between the WHO rankings for health systems and the satisfaction of citizens using those systems.[37] Some countries, such as Italy and Spain, which were given the highest ratings by WHO were ranked poorly by their citizens while other countries, such as Denmark and Finland, were given low scores by WHO but had the highest percentages of citizens reporting satisfaction with their health care systems.[37] WHO staff, however, say that the WHO analysis does reflect system "responsiveness" and argue that this is a superior measure to consumer satisfaction, which is influenced by expectations.[38]

Despite larger spending, the United States has a worse infant mortality rate (6.26)[39] and life expectancy (78.11)[40] than the European Union (5.72[39] and 78.67[40]). Various reasons have been suggested to explain the high infant mortality rates in the U.S. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that higher rates of infant mortality in the U.S. are "due in large part to disparities which continue to exist among various racial and ethnic groups in this country, particularly African Americans".[41] Some studies claim the data collected regarding infant mortality and life expectancy do not lend themselves to fair comparison.[42] A CATO Institute survey has stated that Americans are less likely than citizens of other countries, such as Cuba, to abort fetuses with disabilities and other medical problems; the group views this a complicating factor towards these calculations.[43] Other complaints relate to apples-to-oranges comparisons, which calls attention to the fact that different definitions are used to define live births in different nations, and that Europe's definitions are broadly different from that of the USA and Canada. Such differences in basic definitions make statistical equivalences inappropriate. [44]

Another metric used to compare the quality of health care across countries is Years of potential life lost (YPLL). By this measure, the United States comes third to last in the OECD for women (ahead of only Mexico and Hungary) and fifth to last for men (ahead of Poland and Slovakia aditionally), according to OECD data. Yet another measure is Disability-adjusted life year (DALY); again the United States fares relatively poorly.[citation needed] According to Jonathan Cohn, health care scholars prefer these more "finely tuned" statistical measures for international comparisons in place of the relatively "crude" infant mortality and life expectancy.[45]

Access to advanced medical treatments and technologies in the U.S. is greater than in most other developed nations and waiting times may be substantially shorter for treatment by specialists.[46]

The lack of universal coverage contributes to another flaw in the current U.S. health care system: on most dimensions of performance, it underperforms relative to other industrialized countries.[47] In a 2007 comparison by the Commonwealth Fund of health care in the U.S. with that of Germany, Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, the U.S. ranked last on measures of quality, access, efficiency, equity, and outcomes.[47]

The U.S. system is often compared with that of its northern neighbor, Canada (see Canadian and American health care systems compared). Canada's system is largely publicly funded. In 2006, Americans spent an estimated $6,714 per capita on health care, while Canadians spent US$3,678.[48] This amounted to 15.3% of U.S. GDP in that year, while Canada spent 10.0% of GDP on health care.

A 2007 review of all studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the U.S. found that "health outcomes may be superior in patients cared for in Canada versus the United States, but differences are not consistent."[49]

History of reform efforts

U.S. efforts to achieve universal coverage began with Theodore Roosevelt, who had the support of progressive health care reformers in the 1912 election but was defeated.[50] And President Harry S Truman called for universal health care as a part of his Fair Deal in 1949 but strong opposition stopped that part of the Fair Deal.[citation needed]

The Medicare program was established by legislation signed into law on July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Medicare is a social insurance program administered by the United States government, providing health insurance coverage to people age 65 and over, or who meet other special criteria. The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 (COBRA) amended the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) to give some employees the ability to continue health insurance coverage after leaving employment.

Health care reform was a major concern of the Bill Clinton administration headed up by First Lady Hillary Clinton; however, the 1993 Clinton health care plan was not enacted into law. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) made it easier for workers to keep health insurance coverage when they change jobs or lose a job, and also made use of national data standards for tracking, reporting and protecting personal health information.

During the 2004 presidential election, both the George Bush and John Kerry campaigns offered health care proposals.[51][52] As president, Bush signed into law the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act which included a prescription drug plan for elderly and disabled Americans.[53]

Health reform and the 2008 presidential election

Both of the major party presidential candidates offered positions on health care.

John McCain's proposals focused on open-market competition rather than government funding. At the heart of his plan were tax credits - $2,500 for individuals and $5,000 for families who do not subscribe to or do not have access to health care through their employer. To help people who are denied coverage by insurance companies due to pre-existing conditions, McCain proposed working with states to create what he called a "Guaranteed Access Plan."[54]

Barack Obama called for universal health care. His health care plan called for the creation of a National Health Insurance Exchange that would include both private insurance plans and a Medicare-like government run option. Coverage would be guaranteed regardless of health status, and premiums would not vary based on health status either. It would have required parents to cover their children, but did not require adults to buy insurance.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that the two plans had different philosophical focuses. They described the purpose of the McCain plan as to "make insurance more affordable," while the purpose of the Obama plan was for "more people to have health insurance."[55] The Des Moines Register characterized the plans similarly.[56]

A poll released in early November 2008, found that voters supporting Obama listed health care as their second priority; voters supporting McCain listed it as fourth, tied with the war in Iraq. Affordability was the primary health care priority among both sets of voters. Obama voters were more likely than McCain voters to believe government can do much about health care costs.[57]

Public policy debate

The political debate over health care reform has for several decades revolved around the questions of whether fundamental reform of the system is needed, what form those reforms should take, and how they should be funded. Issues regarding publicly funded health care are frequently the subject of political debate.[58] Whether or not a publicly funded universal health care system should be implemented is one such example.[59]

In spite of the amount spent on health care in the U.S., a 2008 report by the Commonwealth Fund ranked the United States last in the quality of health care among the 19 compared countries.[60] Opponents of government intervention, such as the Cato Institute and the Manhattan Institute, argue that the U.S. system performs better in some areas such as the responsiveness of treatment, the amount of technology available, and higher cure rates for some serious illnesses such as colon, lung, and prostate cancer in men.[43][61]

According to economist and former US Secretary of Labor, Robert Reich, only a "big, national, public option" can force insurance companies to cooperate, share information, and reduce costs. Scattered, localized, "insurance cooperatives" are too small to do that and are "designed to fail" by the moneyed forces opposing Democratic health care reform.[62][63]

Current reform advocacy

General strategies

Mayo Clinic President and CEO Denis Cortese has advocated an overall strategy to guide reform efforts. He argued that the U.S. has an opportunity to redesign its healthcare system and that there is a wide consensus that reform is necessary. He articulated four "pillars" of such a strategy:[64]

- Focus on value, which he defined as the ratio of quality of service provided relative to cost;

- Pay for and align incentives with value;

- Cover everyone;

- Establish mechanisms for improving the healthcare service delivery system over the long-term, which is the primary means through which value would be improved.

Writing in The New Yorker, surgeon Atul Gawande further distinguished between the delivery system, which refers to how medical services are provided to patients, and the payment system, which refers to how payments for services are processed. He argued that reform of the delivery system is critical to getting costs under control, but that payment system reform (e.g., whether the government or private insurers process payments) is considerably less important yet gathers a disproportionate share of attention. Gawande argued that dramatic improvements and savings in the delivery system will take "at least a decade." He recommended changes that address the over-utilization of healthcare; the refocusing of incentives on value rather than profits; and comparative analysis of the cost of treatment across various healthcare providers to identify best practices. He argued this would be an iterative, empirical process and should be administered by a "national institute for healthcare delivery" to analyze and communicate improvement opportunities.[65]

A report published by the Commonwealth Fund in December 2007 examined 15 federal policy options and concluded that, taken together, they had the potential to reduce future increases in health care spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. These options included increased use of health information technology, research and incentives to improve medical decision making, reduced tobacco use and obesity, reforming the payment of providers to encourage efficiency, limiting the tax federal exemption for health insurance premiums, and reforming several market changes such as resetting the benchmark rates for Medicare Advantage plans and allowing the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate drug prices. The authors based their modeling on the effect of combining these changes with the implementation of universal coverage. The authors concluded that there are no magic bullets for controlling health care costs, and that a multifaceted approach will be needed to achieve meaningful progress.[66]

Over-utilization of services and comparative effectiveness research

Over-utilization of healthcare services refers to when a patient overuses a doctor or to a doctor ordering more tests or services than may be required to address a particular condition effectively. Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. According to economist Peter A. Diamond and research cited by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.[67] Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. OMB Director Peter Orszag stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."[68]

Independent advisory panels

President Obama has proposed an "Independent Medicare Advisory Panel" (IMAC) to make recommendations on Medicare reimbursement policy and other reforms. Comparative effectiveness research would be one of many tools used by the IMAC. The IMAC concept was endorsed in a letter from several prominent healthcare policy experts, as summarized by OMB Director Peter Orszag:[69]

Their support of the IMAC proposal underscores what most serious health analysts have recognized for some time: that moving toward a health system emphasizing quality rather than quantity will require continual effort, and that a key objective of legislation should be to put in place structures (like the IMAC) that facilitate such change over time. And ultimately, without a structure in place to help contain health care costs over the long term as the health market evolves, nothing else we do in fiscal policy will matter much, because eventually rising health care costs will overwhelm the federal budget.

Both Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. Denis Cortese and Surgeon/Author Atul Gawande have argued that such panel(s) will be critical to reform of the delivery system and improving value. Washington Post columnist David Ignatius has also recommended that President Obama engage someone like Cortese to have a more active role in driving reform efforts.[70]

Tax reform

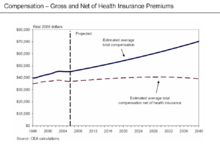

The Congressional Budget Office has described how the tax treatment of insurance premiums may affect behavior:[71]

One factor perpetuating inefficiencies in health care is a lack of clarity regarding the cost of health insurance and who bears that cost, especially employment-based health insurance. Employers’ payments for employment-based health insurance and nearly all payments by employees for that insurance are excluded from individual income and payroll taxes. Although both theory and evidence suggest that workers ultimately finance their employment-based insurance through lower take-home pay, the cost is not evident to many workers...If transparency increases and workers see how much their income is being reduced for employers’ contributions and what those contributions are paying for, there might be a broader change in cost-consciousness that shifts demand.

Peter Singer wrote in the New York Times that the current exclusion of insurance premiums from compensation represents a $200 billion subsidy for the private insurance industry and that it would likely not exist without it.[72]

Employer-provided health insurance receives uncapped tax benefits. According to the OECD, it "encourages the purchase of more generous insurance plans, notably plans with little cost sharing, thus exacerbating moral hazard".[73] Consumers want unfettered access to medical services; they also prefer to pay through insurance or tax rather than out of pocket. These two needs create cost-efficiency challenges for health care.[74] Some studies have found no consistent and systematic relationship between the type of financing of health care and cost containment.[75]

Premium tax subsidies to help individuals purchase their own health insurance have also been suggested as a way to increase coverage rates. Research confirms that consumers in the individual health insurance market are sensitive to price. It appears that price sensitivity varies among population subgroups and is generally higher for younger individuals and lower income individuals. However, research also suggests that subsidies alone are unlikely to solve the uninsured problem in the U.S.[76][77]

Enhancing consumer choice and competition

There are various ways in which insurance distorts typical free-market behavior. For example, a fully-insured person has no incentive to "shop around" for the best price and would insist on the best treatment available, regardless of cost. Employees typically have limited health insurance options through their employers, who may also face limited choices of insurers in their geographic area or state. In addition, the consumers of health care often lack basic information compared to the medical professionals they buy it from, and fully informed choices (particularly in emergencies) are often implausible.

Meanwhile, health insurance companies and care providers also suffer from information asymmetry, as patients are almost always more aware of their particular family histories and risky behaviors than the firms are. Price theory dictates that the risk cost associated with this lack of information gets passed on to consumers. Demand is likely to be inelastic. The medical profession potentially may set rates that are well above ideal market value, and they are controlled by licensing requirements, with some degree of monopoly or oligopoly control over prices. Monopolies are made more likely by the variety of specialists and the importance of geographic proximity. Private insurers have been perhaps the only stabilizing force, as they pay a contractually fixed cost for a given procedure. With no more than one or two heart specialists or brain surgeons to choose from, competition for patients between such experts is limited, so contractually pre-arranged pricing helps reduce supply-limited pricing.

Some reform proposals try to overcome these challenges by creating more competitive markets for insurance and providing individuals with additional information and financial resources with which to purchase services. Republican Newt Gingrich described such an approach:[78]

"The answer is more market competition -- giving consumers more choices, more information and more control. Here is one example. There are more than 1,300 health insurance companies in this country, but currently, consumers can buy only a product licensed in each individual state. Creating a nationwide health insurance market where any individual or group can shop for less expensive coverage from another state would provide more choices, forcing private plans to create better products, improve services and lower prices. We must also equip individuals with information on healthcare cost and quality. Releasing the Medicare-claims history of doctors and hospitals (with patients' personal information removed) would give Americans more knowledge to choose the most efficient institutions, practitioners and the most effective treatments. Inexplicably, this taxpayer-funded data remain locked away. Of course, some Americans also need financial resources to pay for their healthcare choices. Tax credits are one way to help consumers purchase private healthcare coverage, or we could allow individuals to deduct the cost of insurance they purchase, just as employers do now. These are just some solutions to create competition to drive down costs while increasing quality."

Increased use of preventive care

Increased use of preventive care is often suggested as a way of reducing health care spending. Research suggests, however, that in most cases prevention does not produce significant long-term cost savings. Preventive care is typically provided to many people who would never become ill, and for those who would have become ill, it is partially offset by the health care costs during additional years of life.[79]

Coverage mandates

Reforming or restructuring the private health insurance market is often suggested as a means for achieving health care reform in the U.S. Insurance market reform has the potential to increase the number of Americans with insurance, but is unlikely to significantly reduce the rate of growth in health care spending.[80] Careful consideration of basic insurance principles is important when considering insurance market reform, in order to avoid unanticipated consequences and ensure the long-term viability of the reformed system.[81] According to one study conducted by the Urban Institute, if not implemented on a systematic basis with appropriate safeguards, market reform has the potential to cause more problems than it solves.[80]

Since most Americans with private coverage receive it through employer-sponsored plans, many have suggested employer "pay or play" requirements as a way to increase coverage levels (i.e., employers that do not provide insurance would have to pay a tax instead). However, research suggests that current pay or play proposals are limited in their ability to increase coverage among the working poor. These proposals generally exclude small firms, do not distinguish between individuals who have access to other forms of coverage and those who do not, and increase the overall compensation costs to employers.[82]

Congress is debating bills such as the America's Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009, which would prevent insurers from excluding persons from coverage based on pre-existing medical conditions and limit the ability of insurance companies to cancel coverage.

Arguing against requiring individuals to buy coverage, the Cato Institute has asserted that the Massachusetts' law forcing everyone to buy insurance caused costs there to increase faster than in the rest of the country.[83] Arguing for a single-payer health care system, Marcia Angell, former editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, called the Massachusetts mandates "a windfall for the insurance industry" and wrote, "Premiums are rising much faster than income, benefit packages are getting skimpier, and deductibles and co-payments are going up."[84] The Boston Globe reported that, since Massachusetts mandated the uninsured to purchase insurance, emergency visits and costs have increased;[85] insurance premiums have increased faster than the rest of the United States, and are now the highest in the country.[86] Karen Davenport, director of health policy at the Center for American Progress, argued that "before making coverage mandatory, we need to reform the health insurance market, strengthen public health insurance programs, and finance premium subsidies for people who can’t afford coverage on their own."[87]

Reform of doctor's incentives

Critics have argued that the healthcare system has several incentives that drive costly behavior. Two of these include:[88]

- Doctors are typically paid for services provided rather than with a salary. This provides a financial incentive to increase the costs of treatment provided.

- Patients that are fully insured have no financial incentive to minimize the cost when choosing from among alternatives. The overall effect is to increase insurance premiums for all.

Gawande quoted one surgeon who stated: "We took a wrong turn when doctors stopped being doctors and became businessmen." Gawande identified various revenue-enhancing approaches and profit-based incentives that doctors were using in high-cost areas that may have caused the over-utilization of healthcare. He contrasted this with lower-cost areas that used salaried doctors and other techniques to reward value, referring to this as a "battle for the soul of American medicine."[65]

Medical malpractice liability costs and tort reform

Critics have argued that medical malpractice costs (insurance and lawsuits, for example) are significant and should be addressed via tort reform.[89]

How much these costs are is a matter of debate. Some have argued that malpractice lawsuits are a major driver of medical costs.[90] A 2005 study estimated the cost around 0.2%, and in 2009 insurer WellPoint Inc. said "liability wasn’t driving premiums."[91] A 2006 study found neurologists in the United States ordered more tests in theoretical clinical situations posed than their German counterparts; U.S. clinicians are more likely to fear litigation which may be due to the teaching of defensive strategies which are reported more often in U.S. teaching programs.[92] Counting both direct and indirect costs, other studies estimate the total cost of malpractice between 5% and 10% of total U.S. medical costs.[93]

In August 2009, physician and former Democratic National Committee Chairman Howard Dean explained why tort reform was omitted from the Congressional health care reform bills then under consideration: "When you go to pass a really enormous bill like that, the more stuff you put it in it, the more enemies you make, right?...And the reason tort reform is not on the bill is because the people who wrote it did not want to take on the trial lawyers in addition to everybody else they were taking on. That is the plain and simple truth."[94][95]

Others have argued that even successful tort reform might not lead to lower aggregate liability. For example, the current contingent fee system skews litigation towards high-value cases while ignoring meritorious small cases; aligning litigation more closely with merit might thus increase the number of small awards, offsetting any reduction in large awards.[96] A New York study found that only 1.5% of hospital negligence led to claims; moreover, the CBO observed that "health care providers are generally not exposed to the financial cost of their own malpractice risk because they carry liability insurance, and the premiums for that insurance do not reflect the records or practice styles of individual providers but more-general factors such as location and medical specialty."[97] Given that total liability is small relative to the amount doctors pay in malpractice insurance premiums, alternative mechanisms have been proposed to reform malpractice insurance.[98]

In 2004, the CBO studied restrictions on malpractice awards proposed by the George W. Bush Administration and members of Congress; CBO concluded that "the evidence available to date does not make a strong case that restricting malpractice liability would have a significant effect, either positive or negative, on economic efficiency."[99] Empirical data and reporting have since shown that some of the highest medical costs are now in states where tort reform had already caused malpractice premiums and lawsuits to drop substantially; unnecessary and injurious procedures are instead caused by a system "often driven to maximize revenues over patient needs."[100][101][102]

Rationing of care

Healthcare rationing may refer to the restriction of medical care service delivery based on any number of objective or subjective criteria. Republican Newt Gingrich argued that the reform plans supported by President Obama expand the control of government over healthcare decisions, which he referred to as a type of healthcare rationing.[103] However, President Barack Obama has argued that U.S. healthcare is already rationed, based on income, type of employment, and pre-existing medical conditions, with nearly 46 million uninsured. He argued that millions of Americans are denied coverage or face higher premiums as a result of pre-existing medical conditions.[104]

Former Republican Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson argued that some form of rationing is inevitable and desirable considering the state of U.S. finances and the trillions of dollars of unfunded Medicare liabilities. He estimated that 25-33% of healthcare services are provided to those in the last months or year of life and advocated restrictions in cases where quality of life cannot be improved. He also recommended that a budget be established for government healthcare expenses, through establishing spending caps and pay-as-you-go rules that require tax increases for any incremental spending. He has indicated that a combination of tax increases and spending cuts will be required. All of these issues would be addressed under the aegis of a fiscal reform commission.[105]

Rationing by price means accepting that there is no triage according to need. Thus in the private sector it is accepted that some people get expensive surgeries such as liver transplants or non life threatening ones such as cosmetic surgery, when others fail to get cheaper and much more cost effective care such as prenatal care, which could save the lives of many fetuses and newborn children. Some places, like Oregon for example, do explicitly ration Medicaid resources using medical priorities.[106]

Payment system reform

The payment system refers to the billing and payment for medical services, which is distinct from the delivery system through which the services are provided. Converting to a single-payer system is seen by proponents as a solution to flaws in the current system. Economist Paul Krugman argued in 2005 that the U.S. converting to a single-payer system would save approximately $200 billion annually, mainly due to the removal of insurance company overhead. He stated this would more than offset the cost of providing coverage to those presently uninsured.[107]

Proponents of health care reform argue that moving to a single-payer system would reallocate the money currently spent on the administrative overhead required to run the hundreds[108] of insurance companies in the U.S. to provide universal care.[109] An often-cited study by Harvard Medical School and the Canadian Institute for Health Information determined that some 31 percent of U.S. health care dollars, or more than $1,000 per person per year, went to health care administrative costs.[110] Other estimates are lower. One study of the billing and insurance-related (BIR) costs borne not only by insurers but also by physicians and hospitals found that BIR among insurers, physicians, and hospitals in California represented 20-22% of privately insured spending in California acute care settings.[111]

Advocates of "single-payer" argue that shifting the U.S. to a single-payer health care system would provide universal coverage, give patients free choice of providers and hospitals, and guarantee comprehensive coverage and equal access for all medically necessary procedures, without increasing overall spending. Shifting to a single-payer system, by this view, would also eliminate oversight by managed care reviewers, restoring the traditional doctor-patient relationship.[112] Among the organizations in support of single-payer health care in the U.S. is Physicians for a National Health Program (PNHP), an organization of some 17,000 American physicians, medical students, and health professionals.[113]

Healthcare technology

The Congressional Budget Office has concluded that increased use of health information technology has great potential to significantly reduce overall health care spending and realize large improvements in health care quality providing that the system is integrated. The use of health IT in an unintegrated setting will not realize all the projected savings. [114]

Common arguments for and against nationalized health care

Template:MultiCol From supporters:

- In most cases, people have little influence on whether or not they will contract an illness. Consequently, illness may be viewed as a fundamental part of what it means to be human and, as such, access to treatment for illness should be based on acknowledgement of the human condition, not the ability to pay[10][115][116][117] or entitlement.[118] Therefore, health care may be viewed as a fundamental human right itself or as an extension of the right to life. [119]

- Since people perceive universal health care as free, they are more likely to seek preventative care which, in the long run, lowers their overall health care expenditure by focusing treatment on small, less expensive problems before they become large and costly.[120]

- A universal health care system allows for a larger capital base than can be offered by free market insurers (without violating antitrust laws). A larger capital base "spreads out" the cost of a payout among more people, lowering the cost to the individual.

- Universal health care would provide for uninsured adults who may forgo treatment needed for chronic health conditions.[121]

- In most free-market situations, the consumer of health care is entirely in the hands of a third party who has a direct personal interest in persuading the consumer to spend money on health care in his or her practice. The consumer is not able to make value judgments about the services judged to be necessary because he or she may not have sufficient expertise to do so.[122] This, it is claimed, leads to a tendency to over produce. In socialized medicine, hospitals are not run for profit and doctors work directly for the community and are assured of their salary. They have no direct financial interest in whether the patient is treated or not, so there is no incentive to over provide. When insurance interests are involved this furthers the disconnect between consumption and utility and the ability to make value judgments. [123] Others argue that the reason for over production is less cynically driven but that the end result is much the same.[124].

- The profit motive in medicine values money above public benefit.[125] For example, pharmaceutical companies have reduced or dropped their research into developing new antibiotics, even as antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria are increasing, because there's less profit to be gained there than in other drug research.[126] Those in favor of universal health care posit that removing profit as a motive will increase the rate of medical innovation.[127]

- Paul Krugman and Robin Wells say that in response to new medical technology, the American health care system spends more on state-of-the-art treatment for people who have good insurance, and spending is reduced on those lacking it.[128]

- The profit motive adversely affects the cost and quality of health care. If managed care programs and their concomitant provider networks are abolished, then doctors would no longer be guaranteed patients solely on the basis of their membership in a provider group and regardless of the quality of care they provide. Theoretically, quality of care would increase as true competition for patients is restored.[129]

- Wastefulness and inefficiency in the delivery of health care would be reduced.[130] A single payer system could save $286 billion a year in overhead and paperwork.[131] Administrative costs in the U.S. health care system are substantially higher than those in other countries and than in the public sector in the U.S.: one estimate put the total administrative costs at 24 percent of U.S. health care spending.[132] It might only take one government agent to do the job of two health insurance agents.[133] According to one estimate roughly 50% of health care dollars are spent on health care, the rest go to various middlemen and intermediaries. A streamlined, non-profit, universal system would increase the efficiency with which money is spent on health care.[134]

- About 60% of the U.S. health care system is already publicly financed with federal and state taxes, property taxes, and tax subsidies - a universal health care system would merely replace private/employer spending with taxes. Total spending would go down for individuals and employers.[135]

- Several studies have shown a majority of taxpayers and citizens across the political divide would prefer a universal health care system over the current U.S. system[136][137][138]

- America spends a far higher percentage of GDP on health care than any other country but has worse ratings on such criteria as quality of care, efficiency of care, access to care, safe care, equity, and wait times, according to the Commonwealth Fund.[139]

- A universal system would align incentives for investment in long term health-care productivity, preventive care, and better management of chronic conditions.[120]

- The Big Three of U.S. car manufacturers have cited health-care provision as a financial disadvantage. The cost of health insurance to U.S. car manufacturers adds between $900 and $1,400 to each car made in the U.S.A.[140]

- In countries in Western Europe with public universal health care, private health care is also available, and one may choose to use it if desired. Most of the advantages of private health care continue to be present, see also Two-tier health care.[141]

- Universal health care and public doctors would protect the right to privacy between insurance companies and patients.[142]

- Public health care system can be used as independent third party in disputes between employer and employee.[143]

- A study of hospitals in Canada found that death rates are lower in private not-for-profit hospitals than in private for-profit hospitals.[144]

- A universal single-payer system would significantly lower administrative costs. Multiple peer-reviewed studies estimate the administrative savings alone from such a switch to be over $200 billion.[145] Medicare has a 4% overhead compared to 14% of total private insurance expenditures.[146]

- In a private system, insurance companies may be motivated by moral hazard to cancel the insurance policies of the sick, which is called rescission. Thus, unlike the situation under national coverage, individuals find out that they have no health coverage when it is too late to do anything about it.[147]

| class="col-break " |

From opponents:

- Health care is not a right. [11][148] Thus, it is not the responsibility of government to provide health care.[149]

- Free health care can lead to overuse of medical services, and hence raise overall cost.[150][151]

- Universal health coverage does not in practice guarantee universal access to care. Many countries offer universal coverage but have long wait times or ration care.[43]

- The federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act requires hospitals and ambulance services to provide emergency care to anyone regardless of citizenship, legal status or ability to pay.[152][153][154][155]

- Eliminating the profit motive will decrease the rate of medical innovation and inhibit new technologies from being developed and utilized.[156] [157]

- Publicly-funded medicine leads to greater inefficiencies and inequalities. [11][156][158] Opponents of universal health care argue that government agencies are less efficient due to bureaucracy.[158] Universal health care would reduce efficiency because of more bureaucratic oversight and more paperwork, which could lead to fewer doctor-patient visits. [159] Advocates of this argument claim that the performance of administrative duties by doctors results from medical centralization and over-regulation, and may reduce charitable provision of medical services by doctors.[148]

- Converting to a single-payer system could be a radical change, creating administrative chaos.[160]

- The extra spending in the U.S. is justified if expected life span increases by only about half a year as a result.[161]

- Unequal access and health disparities still exist in universal health care systems.[162]

- 70% of health care costs are a direct result from behavior and therefore preventable. By utilizing market-based solutions that create incentives for healthy behavior, the government can ultimately reduce our nation's health-care bill by 40%. [163]

- The problem of rising health care costs is occurring all over the world; this is not a unique problem created by the structure of the U.S. system.[43]

- Universal health care suffers from the same financial problems as any other government planned economy. It requires governments to greatly increase taxes as costs rise year over year. Universal health care essentially tries to do the economically impossible.[164] Empirical evidence on the Medicare single payer-insurance program demonstrates that the cost exceeds the expectations of advocates.[165] As an open-ended entitlement, Medicare does not weigh the benefits of technologies against their costs. Paying physicians on a fee-for-service basis also leads to spending increases. As a result, it is difficult to predict or control Medicare's spending.[162] The Washington Post reported in July 2008 that Medicare had "paid as much as $92 million since 2000" for medical equipment that had been ordered in the name of doctors who were dead at the time.[166] Medicare's administrative expense advantage over private plans is less than is commonly believed.[167][168][169][170] Large market-based public program such as the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program and CalPERS can provide better coverage than Medicare while still controlling costs as well.[171][172]

- National health systems tend to be more effective as they incorporate market mechanisms and limit centralized government control.[43]

- Some commentators have opposed publicly-funded health systems on ideological grounds, arguing that public health care is a step towards socialism and involves extension of state power and reduction of individual freedom.[173]

- The right to privacy between doctors and patients could be eroded if government demands power to oversee the health of citizens.[174]

- Universal health care systems, in an effort to control costs by gaining or enforcing monopsony power, sometimes outlaw medical care paid for by private, individual funds.[175][176]

- Some supporters of American health care reform oppose American health care tort reform (litigation reform).[177]

- The Blue Dog Democrats, support some reforms but oppose other proposals because they cost too much. CNN reports that "Blue Dogs had threatened to derail the bill...because of concerns that it costs too much and fails to address systemic problems in the nation's ailing health care industry."[178]

- Wait times for medical care have been demonstrated in a fully government run health care system to increase substantially compared to a privatized system. Ontario's average wait time between seeing a general care physician and receiving treatment is 15.0 weeks, nearly 4 months. [179]

- The BBC reports that "the (Democratic) party is deeply divided between those that want a publicly-run insurance scheme and those alarmed by the borrowing necessary to fund it" [180]

Other arguments for nationalized health care

Democrats are far more supportive of nationalized health care than are Republicans and overall more Democrats would support a socialized medicine based reform than would not,[181] arguing that it has several advantages over the for-profit, free market system. It has been suggested that the largest obstacle is a lack of political will.[182]

Some advocates of nationalized health care argue that conservatives and many Republicans have historically fought nationalized health care, viewing it as an expansion of government that violates their free-market, limited federal government ideology. Conservative reform proposals focus on enhanced private competition to lower costs and tax reform.[183][184] A New York Times editorial recently asserted:

In recent weeks, it has become inescapably clear that Republicans are unlikely to vote for substantial reform this year. Many seem bent on scuttling President Obama’s signature domestic issue no matter the cost. As Senator Jim DeMint, Republican of South Carolina, so infamously put it: “If we’re able to stop Obama on this, it will be his Waterloo. It will break him.”[185]

Other arguments against nationalized health care

While polling data indicate that U.S. citizens are concerned about health care costs and there is substantial support for some type of reform (see Public opinion, below) most are generally satisfied with the quality of their own health care. According to a Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health in 2003, 86.9% of Americans reported being "satisfied" or "very satisfied" with their health care services, compared to 83.2% of Canadians.[186] In the same study, 93.6% of Americans reported being "satisfied" or "very satisfied" with their physician services, compared to 91.5% of Canadians (according to the study authors, that difference was not statistically significant).

Some U.S. reformers argue for other, more incremental changes to achieve universal health care, such as tax credits or vouchers.[187] However, proponents of a single-payer system, such as Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, assert that incremental changes in a free-market system are "doomed to fail."[188]

Current reform proposals

Obama administration proposals

In July 2008, candidate Obama promised to "bring down premiums by $2,500 for the typical family." His advisers have said that the $2,500 premium reduction includes, in addition to direct premium savings, the average family's share of the reduction in employer-paid health insurance premiums and the reduction in the cost of government health programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. Ken Thorpe of Emory University issued estimates that support Obama's proposal. Other health analysts, such as Joe Antos of the American Enterprise Institute, Karen Davis of the Commonwealth Fund and Jonathan B. Oberlander of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill expressed skepticism that Obama's proposals would achieve the stated level of cost savings.[189]

A September 2008 critique of Obama's health care ideas published in Health Affairs concludes that it does not address the core economic causes of rising health care spending, but would "greatly increase" federal regulation of health coverage.[190] Its authors include a volunteer adviser to the presidential campaign of Senator John McCain and a scholar with the American Enterprise Institute.[191]

The proposal includes implementing guaranteed eligibility for affordable health care for all Americans, paid for by insurance reform, reducing costs, and requiring employers to either furnish meaningful coverage or contribute to a new public plan.[192][193] He would provide for mandatory health care insurance for children.

The outlines of Obama's health care proposal were described in his October 2008 campaign document entitled "Barack Obama and Joe Biden’s plan to lower health care costs and ensure affordable, accessible health coverage for all."[194]. The plan aims to "improve efficiency and lower costs in the health care system by adopting state-of-the-art health information technology systems; by ensuring that patients receive and providers deliver the best possible care, including prevention and chronic disease management services; reforming the market structure to increase competition; and offering federal reinsurance to employers to help ensure that unexpected or catastrophic illnesses do not make health insurance unaffordable or out of reach for businesses and their employees."

For those not insured through employment, Obama's October 2008 proposal includes a National Health Insurance Exchange that would include both private insurance plans and a Medicare-like, government-run option. Coverage would be guaranteed regardless of health status, and premiums would not vary based on health status either. The campaign estimated the cost of the program at $60 billion annually.[195] According to the Associated Press, the program will need to attract young, healthy people into buying coverage to work, but at the state level guaranteed issue requirements have "often had the opposite effect." The plan requires that parents cover their children, but does not require adults to buy insurance.[195]

An April 2009 reform plan, which President Obama was said to support and which is thought to be gaining support in Congress, would give the public the choice of a public sector competitor in the private health insurance market. An article in The Economist said that the inclusion of a public sector option could trigger insurance opposition which, in conjunction with employer health-care provider opposition, could kill health care reform. [196]

Although in 2008 then-Senator Obama campaigned against requiring adults to buy insurance, in July 2009 President Obama reportedly "changed his mind" and announced that he was "now in favor of some sort of individual mandate as long as there's a hardship exemption."[197] Then, in contrast to earlier advocacy of a publicly-funded health care program, in August 2009 Obama administration officials announced they would support a health insurance cooperative in response to deep political unrest amongst Congressional Republicans and amongst citizens in town hall meetings held across America.[198][199][200]

Congressional proposals

On August 9, 2009, the New York Times published a primer and table summarizing Congressional proposals including areas of agreement and disagreement.[201] Some provisions of the Congressional proposals are directly contrary to the reform proposals that President Obama campaigned on; for example, the Congressional proposals would mandate all employers and individuals to purchase insurance or pay a penalty, and the Senate Finance Committee proposal would omit a public option from insurance choices.[202]

On May 5, 2009, the U.S. Senate Finance Committee held hearings on Health care reform. On the panel of the "invited stakeholders," no supporter of the Single-payer health care system was invited.[203] The panel featured Republican senators and industry panelists who argued against any kind of expanded health care coverage.[204] The preclusion of the single payer option from the discussion caused significant protest by doctors in the audience.[204]

There is one bill currently before Congress but others are expected to be presented soon. A merged single bill is the likely outcome.[citation needed] The main sticking points at the markup stage of the Affordable Health Choices Act of 2009 currently before the House of Representatives have been in two areas: whether the government should provide a public insurance plan option to compete with the private insurance sector, and whether comparative effectiveness research should be used to contain costs met by the public providers of health care.[citation needed] Some Republicans have expressed opposition to the public insurance option believing that the government will not compete fairly with the private insurers. Republicans have also expressed opposition to the use of comparative effectiveness research (CER) to limit coverage in any public sector plan (including any public insurance scheme or any existing government scheme such as Medicare), which they regard as rationing by the back door.[citation needed] Democrats have claimed that the bill will not do this but are reluctant to introduce a clause that will prevent, arguing that it would limit the right of the Department of Health and Human Services to prevent payments for services that clearly do not work.[citation needed] America's Health Insurance Plans, the umbrella organization of the private health insurance providers in the United States has recently urged the use of CER to cut costs by restricting access to ineffective treatments and cost/benefit ineffective ones. Republican amendments to the bill would not prevent the private insurance sectors from citing CER to restrict coverage and apply rationing of their funds, a situation which would create a competition imbalance between the public and private sector insurers.[citation needed] A proposed but not yet enacted short bill with the same effect is the Republican sponsored Patients Act 2009.[citation needed]

On June 15, 2009, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issued a preliminary analysis of the major provisions of the Affordable Health Choices Act. [205] The CBO estimated the ten-year cost to the federal government of the major insurance-related provisions of the bill at approximately $1.0 trillion.[205] Over the same ten-year period from 2010 to 2019, the CBO estimated that the bill would reduce the number of uninsured Americans by approximately 16 million.[205] At about the same time, the Associated Press reported that the CBO had given Congressional officials an estimate of $1.6 trillion for the cost of a companion measure being developed by the Senate Finance Committee.[206] In response to these estimates, the Senate Finance Committee delayed action on its bill and began work on reducing the cost of the proposal to $1.0 trillion, and the debate over the Affordable Health Choices act became more acrimonious.[207][208] Congressional Democrats were surprised by the magnitude of the estimates, and the uncertainty created by the estimates has increased the confidence of Republicans who are critical of the Obama Administration's approach to health care.[209][210]

On July 2, 2009, the U.S. Congressional Budget Office issued a preliminary estimate of another draft version of the Affordable Health Choices Act.[211] The cost was lower than the earlier estimate, due to several changes in the draft legislation. The premium subsidies were significantly reduced, a penalty was added for employers who do not offer subsidized coverage to their employees, and the ability of workers to claim a subsidy for individual coverage on the basis that their employer's plan was too expensive was limited.[211] The new estimate placed the 10-year net increase in the federal budget deficit at $597 billion, and the net reduction in the uninsured at 20 million.[211] While the proposal included a "public plan" option, the CBO said that it did not have a material effect on either the cost of the proposal or on the number of people who would be covered ". . . largely because the public plan would pay providers of health care at rates comparable to privately negotiated rates—and thus was not projected to have premiums lower than those charged by private insurance plans . . ."[211] The draft proposal evaluated by CBO did not include Medicaid expansions or other subsidies for individuals below 150% of the Federal Poverty Level.[211] In a July New York Times editorial, Paul Krugman said that after adding an expansion of Medicaid for the poor and near-poor "we’re probably looking at between $1 trillion and $1.3 trillion" for the federal budget cost of the reform package (not counting unfunded mandates on employers and individuals).[212]

In late July 2009 the director of the Congressional Budget Office testified that the proposals then under consideration would significantly increase federal spending and did not include the "fundamental changes" needed to control the rapid growth in health care spending.[213][214] The CBO reviewed the potential impact of an independent Medicare Advisory Council, and estimated that it would save $2 billion over 10 years.[215] The advisory panel had been pushed by the Obama administration as a key mechanism for reducing long-term health care costs.[216] Republicans immediately began using the CBO estimate to argue that the Democratic reform proposals would not control health care costs.[216]

State-level reform efforts

A few states have taken serious steps toward universal health care coverage, most notably Minnesota and Massachusetts, with a recent example being the Massachusetts 2006 Health Reform Statute.[217] The influx of more than a quarter of a million newly insured residents has led to overcrowded waiting rooms and overworked primary-care physicians who were already in short supply in Massachusetts.[218] Other states, while not attempting to insure all of their residents, cover large numbers of people by reimbursing hospitals and other health care providers using what is generally characterized as a charity care scheme; New Jersey is perhaps the best example of a state that employs the latter strategy.

Several single payer referendums have been proposed at the state level, but so far all have failed to pass: California in 1994,[219] Massachusetts in 2000, and Oregon in 2002.[220]

The percentage of residents that are uninsured varies from state to state. Texas has the highest percentage of residents without health insurance at 24%.[221] New Mexico has the second highest percentage of uninsured at 22%.[221]

States play a variety of roles in the health care system including purchasers of health care and regulators of providers and health plans,[222] which give them multiple opportunities to try to improve how it functions. While states are actively working to improve the system in a variety of ways, there remains room for them to do more.[223]

San Francisco has established a program to provide health care to all uninsured residents (Healthy San Francisco).

Public opinion

Survey research in recent decades has shown that Americans generally see expanding coverage as a top national priority, and a majority express support for universal health care.[224] There is, however, much more limited support for tax increases to support health care reform.[224][225][226] Most Americans report satisfaction with their own personal health care.[227] As of 2001, most do not support a single-payer system.[225] Polls of public support for a government-run insurance plan to compete with private insurers, the so-called "public option", have varied widely between 40% to 83% in support of such a plan, depending on the particular poll.[228] Most of the recent polls show between 65% and 76% support of having the option to join a public plan.[229]

In an article published in the May/June 2008 issue of Health Affairs, pollsters William McInturff and Lori Weigel concluded that the current health care debate is very similar to that of the early 1990s, when the 1993 Clinton health care plan was under consideration. Similarities noted by the authors include a strong desire for change, a weakening economy, and an increased willingness to accept a larger governmental role in health care. New factors include high military spending and a higher burden placed on businesses by health care costs. However, the authors argue that many of the barriers to reform that existed in the early 1990s are still in play, including a strong resistance to government as the sole provider of care ("'I like national health insurance,' patiently explained one focus-group respondent. 'I just don’t want the government to run it.'"). The authors conclude that incremental change appears more likely than wholesale restructuring of the system.[230]

A poll released in March 2008 by the Harvard School of Public Health and Harris Interactive found that Americans are divided in their views of the U.S. health system, and that there are significant differences by political affiliation. When asked whether the U.S. has the best health care system or if other countries have better systems, 45% said that the U.S. system was best and 39% said that other countries' systems are better. Belief that the U.S. system is best was highest among Republicans (68%), lower among independents (40%), and lowest among Democrats (32%). Over half of Democrats (56%) said they would be more likely to support a presidential candidate who advocates making the U.S. system more like those of other countries; 37% of independents and 19% of Republicans said they would be more likely to support such a candidate. 45% of Republicans said that they would be less likely to support such a candidate, compared to 17% of independents and 7% of Democrats.[231][232] Differing levels of satisfaction with the current system result in differences in the preferred policy solutions of Democrats and Republicans. Democrats are more likely to believe that the primary responsibility for ensuring access to health care should fall on government, while Republicans are more likely to see health care as an individual responsibility, and are more likely to believe that private industry is more effective in providing coverage and controlling cost than government. Democrats are more likely to support higher taxes to expand coverage, and more likely to require everyone to purchase coverage.[233]

A 2008 survey of over two thousand doctors published in Annals of Internal Medicine, shows that physicians support universal health care and national health insurance by almost 2 to 1.[234]

A CBS News/New York Times poll taken in April 2009 found that healthcare is the most important issue after the economy, and that Americans 57 percent of Americans are willing to pay higher taxes for universal healthcare, compared to 38 percent that are not. Also 54 percent of Americans feel that providing health insurance for all is more important than the problem of keeping health costs down (49 percent). [235]

A Pew Research Center poll issued in June 2009 found that "[m]ost Americans believe that the nation’s health care system is in need of substantial changes."[236] However, the survey found that, compared to the early 1990s when the Clinton Health Reform plan was being considered, fewer Americans believed the country was spending too much on health care, fewer believed that the health care system was in crisis, and fewer supported a complete restructuring of the system.[236] Most supported extending coverage to the uninsured and slowing the increase in health care costs, but neither issue found the same level of support as they did in 1993.[236] "[F]ar fewer [said that] health care expenses are a major problem for themselves and their families than was the case in 1993."[236]

A Time Magazine poll from July 2009 asked respondents if they would favor a "national single-payer plan similar to medicare for all" from Congress. The survey found 49% in support with 46% opposed and 5% unsure.[237]

In an August 2009 poll, SurveyUSA showed the majority of Americans (77%) feel that it is either "Quite Important" or "Extremely Important to "give people a choice of both a public plan administered by the federal government and a private plan for their health insurance."[238]

Prescription drug prices

During the 1990s, the price of prescription drugs became a major issue in American politics as the prices of many new drugs increased sharply, and many citizens discovered that neither the government nor their insurer would cover the cost of such drugs. In absolute currency, the U.S. spends the most on pharmaceuticals per capita in the world. However, national expenditures on pharmaceuticals accounted for only 12.9% of total health care costs, compared to an OECD average of 17.7% (2003 figures).[239] Some 23% of out-of-pocket health spending by individuals is for prescription drugs.[240]

See also

- United States National Health Care Act

- Single-payer health insurance

- America's Affordable Health Choices Act

Related articles

- Health care compared - tabular comparisons of the U.S., Canada, and other countries not shown above.

- Healthcare in Taiwan, 6 percent of GDP (~1/4 US cost), universal coverage by a government-run insurer with smart card IDs to fight fraud.

- Health care reform

- Health care reform debate in the United States

- Health economics

- Health insurance exchange

- Health policy analysis

- Health care politics

- List of healthcare reform advocacy groups in the United States

- National health insurance

- Healthcare rationing in the United States

References

- ^ "Medical Debt Huge Bankruptcy Culprit - Study: It's Behind Six-In-Ten Personal Filings". CBS. 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Medical Bills Leading Cause of Bankruptcy, Harvard Study Finds", ConsumerAffairs.com, February 3, 2005 http://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2005/bankruptcy_study.html#ixzz0QdG8hYUvhttp://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2005/bankruptcy_study.html

- ^ a b World Health Organization assess the world's health system. Press Release WHO/44 21 June 2000.

- ^ a b WHO (2009). "World Health Statistics 2009". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2009-08-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gerard F. Anderson, Uwe E. Reinhardt, Peter S. Hussey and Varduhi Petrosyan, "It’s The Prices, Stupid: Why The United States Is So Different From Other Countries", Health Affairs, Volume 22, Number 3, May/June 2003. Accessed February 27, 2008.

- ^ Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations, Institute of Medicine at the National Academies of Science, 2004-01-14, accessed 2007-10-22

- ^ WSJ-Seib-Health Debate Isn't About Health

- ^ "Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations". Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ^ "No Health Insurance? So What?". The Cato Institute. 2002-10-03. Retrieved 2007-10-27.

- ^ a b Center for Economic and Social Rights. "The Right to Health in the United States of America: What Does it Mean?" October 29, 2004. Cite error: The named reference "CESR" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Sade RM. "Medical care as a right: a refutation." N Engl J Med. 1971 December 2;285(23):1288-92. PMID 5113728. (Reprinted as "The Political Fallacy that Medical Care is a Right.")

- ^ a b "National Health Expenditure Data: NHE Fact Sheet," Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, referenced February 26, 2008

- ^ "The World Health Report 2006 - Working together for health."

- ^ "National Health Expenditures, Forecast summary and selected tables", Office of the Actuary in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2008. Accessed March 20, 2008.

- ^ "OECD Health Data 2009 - Frequently Requested Data". Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. June 2009.

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://ocde.p4.siteinternet.com/publications/doifiles/012006061T02.xls

- ^ U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ^ CBO Testimony

- ^ GAO Presentation-January 2008-Slide 17

- ^ Bloomberg-Cardiologists Crying Foul over Medicare Reforms-August 2009

- ^ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2007." U.S. Census Bureau. Issued August 2008.

- ^ "Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2006." U.S. Census Bureau. Issued August 2007.

- ^ a b Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured

- ^ http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/News-Conference-by-the-President-July-22-2009/

- ^ a b Families USA (2009) press release summarizing a Lewin Group study: "New Report Finds 86.7 Million Americans Were Uninsured at Some Point in 2007-2008" [2]

- ^ http://www.familiesusa.org/assets/pdfs/americans-at-risk.pdf

- ^ Washington Post-Zakaria-More Crises Needed?-August 2009

- ^ Meet the Press-Transcript of Sept 13 2009-Dick Durbin Statement

- ^ http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-by-the-President-to-a-Joint-Session-of-Congress-on-Health-Care/

- ^ http://liberty.pacificresearch.org/docLib/20070408_HPPv5n2_0207.pdf

- ^ http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2004-07-01-our-view_x.htm

- ^ http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2004-07-01-our-view_x.htm

- ^ File:Life Expectancy 2005-2010 UN WPP 2006.PNG using: United Nations World Population Prospects: 2006 revision -Table A.17[3]. Life expectancy at birth (years) 2005-2010. All data from the ranking is included, except for Martinique and Guadeloupe (due to imaging difficulties).

- ^ Health system attainment and performance in all Member States, ranked by eight measures, estimates for 1997

- ^ David Gratzer, Why Isn't Government Health Care The Answer?, Free Market Cure, 16 July 2007

- ^ a b Robert J. Blendon, Minah Kim and John M. Benson, "The Public Versus The World Health Organization On Health System Performance", Health Affairs, May/June 2001

- ^ Christopher J.L. Murray, Kei Kawabata, and Nicole Valentine, "People’s Experience Versus People’s Expectations", Health Affairs, May/June 2001

- ^ a b "Infant mortality rate". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 18th August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b "Life expectancy at birth". CIA Factbook. Retrieved 18th August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Infant Mortality Fact Sheet