Superhero: Difference between revisions

rvv |

→Divergent character examples: minor edit to replace improper use of the word "alternatively" |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

*[[Superman]], [[Silver Surfer]], [[Martian Manhunter]] and [[Captain Marvel (Marvel Comics)|Captain Marvel]] (the [[Marvel Comics]] character) are [[extraterrestrial]]s who have, either permanently or provisionally, taken it upon themselves to protect the planet [[Earth]]. |

*[[Superman]], [[Silver Surfer]], [[Martian Manhunter]] and [[Captain Marvel (Marvel Comics)|Captain Marvel]] (the [[Marvel Comics]] character) are [[extraterrestrial]]s who have, either permanently or provisionally, taken it upon themselves to protect the planet [[Earth]]. |

||

* |

*In juxtaposition to them, [[Adam Strange]] is a human being who protects the planet [[Rann]]. |

||

*[[Thor (Marvel Comics)|Thor]] and [[Hercules (comics)|Hercules]] are [[mythology|mythological]] [[god]]s reinterpretted as superheroes. Wonder Woman, while not a goddess, is a member of the [[Amazons|Amazon tribe]] of [[Greek mythology]]. |

*[[Thor (Marvel Comics)|Thor]] and [[Hercules (comics)|Hercules]] are [[mythology|mythological]] [[god]]s reinterpretted as superheroes. Wonder Woman, while not a goddess, is a member of the [[Amazons|Amazon tribe]] of [[Greek mythology]]. |

||

* |

*By contrast, [[Spawn (comics)|Spawn]], [[The Demon (comics)|The Demon]] and [[Ghost Rider]] are actual [[demon]]s, who find themselves manipulated by circumstance to be allies for the forces of good. [[Hellboy]], on the other hand, is a demon who is heroic on his own accord. |

||

*The [[Gargoyles (animated series)|Gargoyles]] are ancient, almost [[myth]]ological creatures who, despite their monstrous appearance, are a benign, intelligent species dedicated to protecting their territories. |

*The [[Gargoyles (animated series)|Gargoyles]] are ancient, almost [[myth]]ological creatures who, despite their monstrous appearance, are a benign, intelligent species dedicated to protecting their territories. |

||

* |

*Characters who have trod the line between superhero and villain include [[Magneto (comics)|Magneto]], [[Juggernaut (comics)|Juggernaut]], [[Emma Frost]], [[Catwoman]], [[Elektra Natchios|Elektra]],and [[Venom (comics)|Venom]]. |

||

*Because the superhero is such an outlandish and recognizable character type, several comedic heroes have been introduced, including [[Super Dupont]], [[The Tick]], [[The Flaming Carrot]], [[The Ambiguously Gay Duo]] and ''[[The Simpsons]]''’ [[Radioactive Man]]. |

*Because the superhero is such an outlandish and recognizable character type, several comedic heroes have been introduced, including [[Super Dupont]], [[The Tick]], [[The Flaming Carrot]], [[The Ambiguously Gay Duo]] and ''[[The Simpsons]]''’ [[Radioactive Man]]. |

||

Revision as of 11:28, 14 January 2006

A superhero is a fictional character who is noted for feats of courage and nobility, who usually has a colorful name and costume and abilities beyond those of normal human beings. A female superhero is called a superheroine.

Since the definitive superhero, Superman, debuted in 1938, the stories of superheroes - ranging from episodic adventures to decades-long sagas - have become an entire genre of fiction that has dominated American comic books and crossed over into several other media.

Common traits

A range of attributes are commonly part of a superhero's make-up, although they are by no means definitive (see Divergent character examples). Most superheroes have a few of the following features:

- Extraordinary powers and abilities, mastery of relevant skills, and/or advanced equipment. Although superhero powers vary widely, superhuman strength, the ability to fly, enhancements of the senses and the ability to project energy of some kind are all common. Some superheroes, such as Batman and Green Hornet, possess no superpowers but have mastered skills such as martial arts and forensic sciences. Others have special equipment, such as Iron Man’s powered armor and Green Lantern’s power ring.

- A strong moral code, including a willingness to risk their own safety in the service of good without expectation of reward.

- A special motivation, such as a sense of responsibility (e.g. Spider-Man), a strong sense of justice (e.g. Captain America), a formal calling (e.g., Captain Marvel), or a personal vendetta against criminals (e.g., The Punisher).

- A secret identity that protects the superhero’s friends and family from becoming targets of his or her enemies. Most superheroes use a descriptive or metaphoric codename for their public deeds.

- A flamboyant and distinctive costume (see Common costume features).

- An underlining motif or theme that affects the hero’s name, costume, personal effects and other aspects of his character (e.g., Batman resembles a large bat, calls his headquarters the "Batcave" and his specialized automobile, which also looks bat-like, the "Batmobile").

- A trademark weapon (e.g., Wonder Woman’s "Lasso of Truth," Captain America’s shield).

- A supporting cast of recurring characters, including the hero's friends, co-workers and/or love interests, who may or may not know of the superhero's secret identity. Often the hero's personal relationships are complicated by his/her dual life.

- An archenemy or a number of enemies that s/he fights repeatedly. Often a nemesis is a superhero’s opposite or foil (e.g., Sabretooth embraces his savage instincts while Wolverine battles his).

- Independent wealth (e.g., Batman or the X-Men's benefactor Professor X) or an occupation that allows for minimal supervision (e.g., Superman's civilian job as a reporter).

- A secret headquarters or base of operations (e.g., Superman's Fortress of Solitude).

- An "origin story" that explains the circumstances by which the character acquired his/her abilities as well as his/her motivation for fighting evil. Many back stories involve tragic elements and/or freak accidents that result in the development of the hero's abilities.

Most superheroes work independently. However, there are also many superhero teams. Some, such as the Fantastic Four and X-Men, have common origins and usually operate as a group. Others, such as DC Comics’s Justice League and Marvel’s Avengers are "all-star" groups consisting of heroes of separate origins who also operate individually.

Some superheroes, especially those introduced in the 1940s, work with a child or teenaged sidekick (e.g., Batman and Robin, Captain America and Bucky). This has become less common since more sophisticated writing and older audiences have lessened the need for characters who specifically appeal to young readers and made such obvious child endangerment seem implausible. Sidekicks themselves are often seen as a separate classification of superheroes.

Superheroes most often appear in comic books, and superhero stories are the dominant genre of American comic books, to the point that the terms "superhero" and "comic book character" are often used synonymously. Superheroes have also been featured in radio serials, prose novels, TV series, movies, and other media. Most of the superheroes who appear in other media are adapted from comics, but there are exceptions.

Marvel Comics Group and DC Comics, Inc., share ownership of the United States trademark for the phrase "Super Heroes" as it applies to comics, and these two companies own a majority of the world’s most famous superheroes. However, throughout comic book history, there have been significant heroes owned by others, such as Captain Marvel, owned by Fawcett Comics (but later acquired by DC) and Spawn, owned by creator Todd McFarlane.

Superheroes are largely an American creation but there have been successful superheroes in other countries, most of whom share the conventions of the American model. For example, Japan has numerous superheroes of its own. Ultraman and Kamen Rider have become popular in Japanese tokusatsu live-action shows, and Science Ninja Team Gatchaman and Sailor Moon are staples of Japanese anime and manga. Other examples include Cybersix from Argentina, Captain Canuck from Canada, Marvelman (known as Miracleman in North America) from the United Kingdom, Nagraj from India and the heroes of AK Comics from Egypt.

Although superhero fiction is considered a subgenre of fantasy/science-fiction, it crosses into many other genres. Many superhero franchises resemble crime fiction (Batman, Daredevil), others horror fiction (Spawn, Hellboy), while others contain aspects of more standard science fiction (Green Lantern, X-Men). Many of the earliest superheroes, such as The Sandman and The Clock, were rooted in the pulp fiction of their predecessors.

Because the fantastic nature of the superhero milieu allows almost anything to happen, particular superhero series frequently cross over into a variety of vastly different genres. In the 1980s series The New Teen Titans, for example, the Titans battled a supernatural satanic cult leader in one story, went off to another galaxy to participate in a space war in the following story, and then returned to Earth and became involved in a gritty urban drama involving young runaways. The content of each of these stories is quite different, yet the same principal characters are involved.

Common costume features

A superhero’s costume helps make him or her recognizable to the general public (both in and outside of fiction). Costumes frequently incorporate the superhero's name and theme. For example Daredevil resembles a red devil, the design of Captain America's costume echoes that of the American flag and Spider-Man’s costume features a web pattern.

Many features of superhero costumes recur frequently, including:

- Superheroes who maintain a secret identity often wear a mask, ranging from the small bands of Green Lantern and Ms. Marvel to the full facemasks of Spider-Man and Black Panther. Most common, however, are masks covering the upper face, leaving the more indistinguishable jaw and neck areas exposed which represents a compromise of a believable disguise while allowing for the character to still show facial expression. These include the masks of Captain America, Batman and The Flash.

- Form-fitting clothing, often referred to as tights or spandex, although the exact material is usually not identified. Such material displays a character’s muscular build.

- A symbol, such as a stylized letter or visual icon, usually on the chest. Examples include Superman’s "S" and Green Lantern's lantern symbol.

- While a vast majority of superheroes do not wear capes, the garment is still closely associated with them, likely due to the fact that two of the most widely-recognized superheroes, Batman and Superman, wear capes.

- When thematically appropriate, some superheroes dress like people from certain professions or subcultures. Zatanna, who possesses wizard-like powers, dresses like a magician and Ghost Rider, who rides a super powered motorcycle, dresses in the garb of a biker.

- While most superhero costumes merely hide the hero’s identity and/or present a recognizable image, parts of some costumes have functional uses. Batman’s utility belt and Spawn’s "necroplasmic armor" have both been of great assistance to the heroes. Iron Man, in particular, wears a variety of powered armor that protects him and provides technological advantages.

- Several heroes of the 1990s, including Cable and many Image Comics characters, rejected the traditional superhero outfit for costumes that appeared more practical and militaristic. Shoulder pads, kevlar-like vests, metal plated armor, knee and elbow pads, and heavy duty belts were all common features. The modern Animal Man is a compromise in this respect with him wearing a standard skintight bodysuit that is worn under a regular jacket which gives him both pockets and a distinctive look.

Character subtypes

In superhero role-playing games (particularly Champions), superheroes are informally organized into categories based on their skills and abilities. Since comic book and role-playing fandom overlap, these labels have carried over into discussions of superheroes outside the context of games:

- "Martial Artist": A hero whose physical abilities are mostly human rather than superhuman but whose combat skills are phenomenal. Some of these characters are actually superhuman (Daredevil, Iron Fist) while others are normal human beings who are extremely skilled and athletic (Batman and related characters, Black Widow, and Elektra).

- "Brick/Tanker": A character with a superhuman degree of strength and endurance and usually an oversized, muscular body, e.g., The Thing, The Hulk, Colossus, Savage Dragon.

- "Blaster": A hero whose main power is a distance attack, e.g., Cyclops, Starfire, Static.

- "Archer": A subvariant of this type who uses bow and arrow-like weapons that have a variety of specialized functions like explosives, glue, nets, rotary drill, etc., e.g., Green Arrow, Hawkeye.

- "Mage": A subvariant of this type who is trained in the use of magic that partially or wholly involves ranged attacks., e.g., Doctor Strange, Doctor Fate.

- "Gadgeteer": A hero who invents special equipment that often imitates superpowers, e.g., Forge, Nite Owl.

- "Armored Hero": A gadgeteer whose powers are derived from a suit of powered armor, e.g., Iron Man, Steel.

- "Speedster": A hero possessing superhuman speed and reflexes, e.g., The Flash, Quicksilver.

- "Mentalist": A hero who possesses psionic abilities, such as telekinesis, telepathy and extra-sensory perception, e.g., Professor X, Jean Grey, Saturn Girl.

- "Shapeshifter": A hero who can manipulate his/her own body to suit his/her needs, such as stretching (Mister Fantastic, Plastic Man) or disguise (Changeling, Chameleon).

- "Sizechanger": A shapeshifter who can alter his/her size, e.g., the Atom (shrinking only), Colossal Boy (growth only), Hank Pym (both).

These categories often overlap. For instance, Batman is a martial artist and a gadgeteer, and Superman is extremely strong and damage resistant and also has ranged attacks (heat vision, superbreath) like an energy blaster and can move quickly like a speedster. The Martian Manhunter excels in every category except martial arts and gadgetry.

Divergent character examples

While the typical superhero is described above, many break the mold:

- Spider-Man has been portrayed as an everyman hero, showing poor judgment and being overwhelmed by the combined responsibilities of his personal life and mission as a superhero.

- The Incredible Hulk is usually defined as a superhero, but he has little self-control and his actions have often either inadvertently or deliberately caused great destruction. As a result, he has been hunted by the military and other superheroes.

- Wolverine of the X-Men has shown a willingness to kill and behave anti-socially. Wolverine belongs to an entire underclass of anti-heroes who are grittier and more violent than classic superheroes, often putting the two groups at odds. Others include Rorschach, Daredevil, Green Arrow, Black Canary, The Punisher and, in some incarnations, Batman.

- Some superheroes have been created and employed by national governments to serve their interests and defend the nation. Examples include Captain America, who was outfitted by and worked for the United States Army during World War II, and Alpha Flight, a superhero team formed by the Canadian government.

- Many superheroes have never had a secret identity, such as Wonder Woman (in her current version) and the members of The Fantastic Four. Others who once had a secret identities, such as Captain America and Steel, have later made their identities public.

- Some superhero identities have been used by more than one person. A character takes on another's name and mission after the original dies, retires or takes on a new identity. Several characters have taken-up the mantles of Green Lantern, The Flash, Captain Canuck,Zorro,Batmanand Robin.

- Superman, Silver Surfer, Martian Manhunter and Captain Marvel (the Marvel Comics character) are extraterrestrials who have, either permanently or provisionally, taken it upon themselves to protect the planet Earth.

- In juxtaposition to them, Adam Strange is a human being who protects the planet Rann.

- Thor and Hercules are mythological gods reinterpretted as superheroes. Wonder Woman, while not a goddess, is a member of the Amazon tribe of Greek mythology.

- By contrast, Spawn, The Demon and Ghost Rider are actual demons, who find themselves manipulated by circumstance to be allies for the forces of good. Hellboy, on the other hand, is a demon who is heroic on his own accord.

- The Gargoyles are ancient, almost mythological creatures who, despite their monstrous appearance, are a benign, intelligent species dedicated to protecting their territories.

- Characters who have trod the line between superhero and villain include Magneto, Juggernaut, Emma Frost, Catwoman, Elektra,and Venom.

- Because the superhero is such an outlandish and recognizable character type, several comedic heroes have been introduced, including Super Dupont, The Tick, The Flaming Carrot, The Ambiguously Gay Duo and The Simpsons’ Radioactive Man.

History of superheroes in comic books

Antecedents

The origins of superheroes can be found in several prior forms of fiction. Many share traits with protagonists of later Victorian literature, such as The Scarlet Pimpernel and Sherlock Holmes.

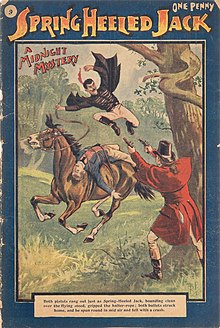

One notable fore-runner of the modern superhero was Spring Heeled Jack, who first emerged as an urban legend in England during the 1830s. Reports of a mysterious figure, apparently capable of superhuman feats of agility and sometimes said to bear unusual weapons including a gas or flame projector and clawed gauntlets, continued for most of the next hundred years. However, it was in the penny dreadfuls, Victorian fore-runners of the comic book format, that Spring Heeled Jack underwent his transformation into a prototypical superhero, complete with a mask and elaborate costume, secret identity as an altruistic, wealthy bachelor, technology-based super powers, concealed base of operations (in a crypt), etc. In many respects Jack was a Victorian-era Batman, emerging decades before his time.

Another early superhero was the Reverend Dr. Christopher Syn, the protagonist of a series of novels by Russell Thorndike. Dr. Syn adopted the masked and costumed identity of the Scarecrow of Romney Marsh to defend his parishioners against the King's press-gangs and tax agents. Set during the 1700s, Thordike's first novel featuring Dr. Syn/the Scarecrow was published in 1915, pre-dating the dual-identity superheroics of Superman, Batman and others by more than twenty years.

The dime novel stories of Zorro and Tarzan also influenced superheroes. Pulp magazine crime fighters, such as Doc Savage, The Shadow and The Spider, and comic strip characters, such as Dick Tracy and The Phantom, were probably the most direct influences.

By modern standards, characters like Doc Savage and The Phantom — normal human beings at or near peak abilities — could be considered superheroes in their own right, but the first appearance of Superman is widely considered the point at which the superhero genre truly began.

Philip Wylie's 1930 novel Gladiator has recently gained attention as a prototype not only of the "classic" superhero, but also of its deconstruction. [1]

Golden Age

In 1938, writer Jerry Siegel and illustrator Joe Shuster, who had previously worked in pulp science fiction magazines, introduced Superman. The character possessed many of the traits that have come to define the superhero, including a secret identity, superhuman powers and a colorful costume including a symbol and cape. His name is also the source of the term "superhero."

DC Comics (which published under the names National and All-American at the time) received an overwhelming response to Superman and, in the months that followed, introduced such superheroes as Batman and his sidekick Robin, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, The Flash, Hawkman, Aquaman and Green Arrow. The first team of superheroes was DC's Justice Society of America, featuring most of the aforementioned characters.

Although DC dominated the superhero market at this time, companies large and small created hundreds of superheroes. Marvel Comics’ Human Torch and Sub-Mariner, Quality Comics’ Plastic Man and Phantom Lady, and Will Eisner's The Spirit (featured in a newspaper insert) were also hits. The era's most popular superhero, however, was Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel, who outsold Superman during the 1940s.

During World War II, superheroes grew in popularity, surviving paper rationing and the loss of many writers and illustrators to service in the armed forces. The need for simple tales of good triumphing over evil may explain the wartime popularity of superheroes. Publishers responded with stories in which superheroes battled the Axis Powers and the introduction of patriotically themed superheroes, most notably Marvel's Captain America.

After the war, superheroes lost popularity. This led to the rise of other genres, especially horror and crime. The lurid nature of these genres sparked a moral crusade in which comics were blamed for juvenile delinquency. The movement was spearheaded by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who argued, among other things, that "deviant" sexual undertones ran rampant in superhero comics. [2]

In response, the comic book industry adopted the stringent Comics Code. By the mid-1950s, only Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman retained a sliver of their prior popularity, although an effort towards complete inoffensiveness that some people considered silly, especially by modern standards. This ended what historians have called the Golden Age of comic books.

Silver Age

In the 1950s, DC Comics, under the editorship of Julius Schwartz, recreated many popular 1940s heroes, launching an era later deemed the Silver Age of comic books. The Flash, Green Lantern, Hawkman and several others were revived with new origin stories. While past superheroes resembled mythological heroes in their origins and abilities, these heroes were inspired by contemporary science fiction. In 1960, DC banded its most popular heroes together in the Justice League of America, which became a sales phenomenon.

Empowered by the return of the superhero at DC, Marvel Comics editor/writer Stan Lee and the artists/co-writers Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko launched a new line of superhero comic books, beginning with The Fantastic Four in 1961. These comics continued DC’s emphasis on science fiction concepts (radiation was a common source of superpowers) but placed greater emphasis on personal conflict and character development. This led to many superheroes that differed greatly from their predecessors with more dramatic potential. Some examples:

- The Thing, a member of The Fantastic Four, was a super strong, but monstrous creature with rock-like skin, whose appearance filled him with self-pity.

- Spider-Man was a teenager who struggled to earn money and maintain his social life in addition to his costumed exploits.

- The Incredible Hulk shared a Jekyll/Hyde-like relationship with his alter ego and was driven by rage.

- The X-Men were "mutants" who gained their powers through genetic mutation and who were hated and feared by the society they sought to protect.

By the early 1970s, the return of the superhero genre, the rise of television as the top medium for light entertainment and the Comics Code Authority’s effect on grittier genres obliterated genres such as westerns, romance, horror, war and crime while the superhero genre underwent a revival. In the coming decades, non-superhero comic book series would occasionally rise to popularity but superheroes and comic books would be forever intertwined in the eyes of the American public.

Deconstruction of the superhero

In the 1970, DC Comics paired Green Arrow and Green Lantern together in a ground-breaking socially-conscious series. Writer Dennis O'Neil portrayed Green Arrow as an angry, street-smart populist and Green Lantern as good-natured but short-sighted authority figure. This is the first instance in which superheroes were classified into two distinct groups, the "classic" superhero and the more brazen anti-hero and the first to suggest that the former had become outdated.

In the 1970s, DC returned Batman to his roots as a dubious vigilante and Marvel introduced several popular anti-heroes, including The Punisher, Wolverine and writer/artist Frank Miller's darker version of Daredevil. These characters were deeply troubled from within. Batman, The Punisher and Daredevil were driven by the crime-related deaths of family members and were continually exposed to slum life. The X-Men’s Wolverine, on the other hand, was a mysterious character who was at odds with his own savage nature.

The trend was taken to a new extreme in the 1986 mini-series Watchmen by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, which was published by DC but took place outside the "DC Universe", with new characters. The superheroes of Watchmen were emotionally unsatisfied, psychologically withdrawn and even sociopathic.

Another story, The Dark Knight Returns (1985-1986) continued Batman’s renovation. This mini-series, written and illustrated by Frank Miller, featured a future Batman returning from retirement. The series portrayed the hero as a madman on a brutal quest to mold society to his will and concluded with a symbolic slugfest against Superman.

Some critics believe that this trend is tied to the cynicism of the 1980s, when the idea of a person selflessly using his extraordinary abilities on a quest for good was no longer believable, but a person with a deep psychological impulse to destroy criminals was. Regardless, both Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns were acclaimed for their artistic ambitiousness and psychological depth and became watermark series, leading to numerous imitations.

Struggles of the 1990s

By the early 1990s, anti-heroes had become the rule rather than the exception, as The Punisher, Wolverine and the grimmer Batman became very popular and marketable characters. Anti-heroes such as the X-Men’s Gambit and Bishop, X-Force's Cable and the Spider-Man adversary Venom became some of the most popular new characters of the early 1990s. This was financial boom time for the industry when a new character could become well-known quickly and, according to many fans, stylistic flair eclipsed character development.

In 1992, Marvel illustrators Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld — all of whom helped popularize anti-heroes in the Spider-Man and X-Men franchises — left Marvel to found Image Comics. Image changed the comic book industry as a haven for creator-owned characters and the first challenger to Marvel and DC in 30 years. Image superhero teams, such as Lee’s WildC.A.Ts and Gen 13, Leifeld’s Youngblood, were instant hits but were criticized as over-muscled, over-sexualized, excessively violent and lacking in unique personality. McFarlane’s occult hero Spawn fared somewhat better in critical respect and long-term sales and his vast popularity led many young creators to gravitate towards the trend of gritty anti-heroes.

To keep ahead of new competitors and continue to the financial boom, Marvel and DC launched headline-grabbing, large-scale storylines that made drastic changes to iconic characters. The "Death of Superman" found the hero killed and resurrected, Batman was physically crippled in the "KnightSaga" storyline, and a clone of Spider-Man vied with the original for the title. While these stories drummed up publicity, fans complained that the essential elements of the franchises had been diluted and they ultimately lost interest.

Throughout the 1990s, several creators deviated from the trends of violent anti-heroes and sensational, large-scale storylines. Painter Alex Ross, writer Kurt Busiek and Alan Moore himself tried to "reconstruct" the superhero genre with acclaimed titles such as Busiek's and Ross' Astro City and Moore's Tom Strong, which combined artistic sophistication and idealism into a superheroic version of retro-futurism. Ross also painted two widely acclaimed mini-series, Marvels (written by Busiek) for Marvel Comics and Kingdom Come for DC, which examined the classic superhero in a more literary context. Kingdom Come also satirized the anti-heroes; Magog, one of the series' antagonists, was a parody of Cable.

By the beginning of the 2000s, most classic superheroes had returned to their roots. However, the comic book industry’s most acclaimed writers could make drastic changes and gain general fan approval, as was the case with Grant Morrison's New X-Men series and Brian Michael Bendis's "Avengers Disassembled" story arc.

As of 2005, a decline in the comic book industry has cut the surplus of anti-heroes, but a revival of superhero films and a rise in the sale of trade paperbacks have kept the superhero genre healthy.

Growth in diversity

From their birth until the early 1960s, superheroes largely conformed to the model of lead characters in American popular fiction in the first half of the 20th century. Hence, the typical superhero was a white, middle to upper class, heterosexual, professional, young-to-middle-aged man. A majority of superheroes still fit this description but, in subsequent decades, many minority characters have broken the mold.

Female characters

The first significant female superhero was DC Comics’s Wonder Woman, created by psychologist William Moulton Marston in 1941 as a role model for young women. She was the only widely popular female superhero for two decades and is arguably still the most famous.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, DC debuted female versions of prominent male superheroes, such as Supergirl, Batwoman, and Hawkgirl, as well as female supporting characters that were successful professionals, such as Superman’s love interest Lois Lane, who starred in a spin-off series aimed at young female readers.

Meanwhile, Marvel Comics introduced The Fantastic Four's Invisible Girl and the X-Men's Marvel Girl, but these characters were physically weak and were portrayed primarily as romantic interests of their teammates. The 1970s saw these heroes become more confident and assertive and the launch of several series starring female superheroes, including Spider-Woman and Ms. Marvel. Initially, some characters were preachy feminist stereotypes, like Ms. Marvel and DC's Power Girl, until writers grew more accustomed with society's changing attitudes.

In subsequent decades, Elektra, Catwoman, Witchblade and Spider-Girl became stars of popular series and the X-Men, one of the few superhero teams to feature as many female characters as male, became the industry's most successful franchise. Storm, Rogue and Psylocke were some of the most popular "X-Women."

Non-Caucasian characters

In the late 1960s, superheroes of other racial groups began to appear in Marvel Comics. In 1966, the company introduced the Black Panther, the first serious black superhero. In 1972, Luke Cage, an African-American "hero-for-hire," became the first black superhero to star in his own series.

In 1971, Marvel introduced Red Wolf, the first Native American hero [3]. Shortly after, he starred in a short-lived eponymous series.

In 1974, Shang Chi, a martial arts hero, became the first Asian hero to star in an American comic book series (The last Asian title character, the 1950s’ Yellow Claw, was a villain, although his main opponent was also Asian. [4]).

Comic book companies were in the early stages of cultural expansion and many of these characters played to specific stereotypes; Cage often employed lingo similar to that of blaxploitation films, Native Americans were often associated with wild animals and Asians were often portrayed as martial artists. Subsequent minority heroes, such as the X-Men’s Storm (the first black, female superhero) and The Teen Titans’ Cyborg would avoid the patronizing nature of the earlier characters as the comics industry became more mature and diverse.

In the 1980s, a recurring character was promoted to Green Lantern: John Stewart, a black ex-Marine. He went on to become one of the most fully fleshed characters, as he had a love/hate relationship with his superpowers, and also suffered a brief spell of paraplegia. However, this did not stop criticisms when he was enrolled into the JLA, fans accusing the creators of including him merely to add diversity.

In 1993, Milestone Comics, an African-American-owned imprint of DC, introduced a line of series that included characters of many ethnic minorities, including several black headliners. The imprint lasted four years, during which it introduced Static, a character adapted into the WB Network series Static Shock.

Gay characters

In 1992, Marvel revealed that Northstar, a member of Alpha Flight, was homosexual, after years of implication. Although some secondary characters in Watchmen were gay, Northstar was the first gay superhero to have a permanent presence in a continuing series. Since then, a few other semi-prominent gay superheroes have emerged, such as Gen13's Rainmaker, The New Mutants’ Karma and The Authority's gay couple Apollo and Midnighter.

The Flash adversary Pied Piper came out of the closet after quitting his criminal activity and becoming a supporting hero.

Recently gay characters were revealed in two Marvel titles, the Ultimate incarnation of Colossus in Ultimate X-Men, and the characters of Wiccan and Hulkling in the series Young Avengers.

Diversified teams

In 1975, Marvel revived the X-Men, introducing a new team with members culled from several different nations, including the German Nightcrawler, the Russian Colossus, the Canadian Wolverine and the Kenyan Storm. The X-Men, which became comic books’ most successful franchise in the coming decade, continued to have a radically diverse roster and an underlining message of tolerance and unity. Ethnic diversity would be an important part of subsequent X-Men-related groups, as well as series that attempted to mimic the X-Men’s success, such as DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes and Teen Titans.

Treatment in other media

Film

Superhero films began as Saturday movie serials aimed at children during the 1940s. The decline of these serials meant the death of superhero films until the release of 1978‘s Superman. Several sequels followed in the 1980s. A popular Batman series lasted from 1989 until 1997. These franchises were initially successful but later sequels in both series fared poorly, stunting the growth of superhero films for a time.

In the early 2000s, blockbusters such as 2000’s X-Men, 2002’s Spider-Man and 2005's Batman Begins have led to dozens of superhero films. The improvements in special effects technology and more sophisticated writing that emulates the spirit of the comic books has drawn in mainstream audiences and caused critics to take superhero films more seriously.

Live-action television series

Several popular but, by modern standards, campy live action superhero programs aired from the early 1950s until the late 1970s. These included The Adventures of Superman starring George Reeves, the psychedelic-colored Batman series of the 1960s starring Adam West and Burt Ward and CBS’s Wonder Woman series of the 1970s starring Lynda Carter. In fact, during the late seventies, CBS gained a reputation as "The Superhero Network", causing it to purge some shows, with only The Incredible Hulk having reached five seasons.

In the 1990s, networks attempted several unconventional uses of the superhero genre in live action shows, including the exceptionally popular Smallville, which reinvents Superman’s origins as teen drama. Other examples include Lois and Clark, Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Alias.

Animation

In the 1940s, Fleischer/Famous Studios produced a number of groundbreaking Superman cartoons, which became the first examples of superheroes in animation.

Since the 1960s, superhero cartoons have been a staple of children’s television, particularly in the USA. However, by the early 1980s, US broadcasting restrictions on violence in children’s entertainment led to series that were extremely tame, a trend exemplified by the series Super Friends.

In the 1990s, Batman: The Animated Series and X-Men led the way for series that displayed advanced animation, mature writing and respect for the comic books on which they were based. This trend continues with Cartoon Network’s successful adaptations of DC's Justice League and Teen Titans.

Radio

In the late 1930s and throughout the 1940s, Superman was one of the most popular radio serials in the United States. Along with Green Hornet and The Shadow, the series helped popularize superheroes during their earliest years. By the early 1950s, the rise of television ended radio serials, including superhero shows.

Prose

Popular superheroes have occasionally been adapted into prose fiction, starting with the 1942 novel Superman by George Lowther. Elliot S! Maggin also wrote two popular Superman novels, Last Son of Krypton and Miracle Monday, in the 1970s. Maggin later penned the 1998 novelization of the Kingdom Come comics series.

Juvenile novels featuring Batman, Spider-Man, the X-Men, and the Justice League have also been published from time to time, often marketed in association with popular TV series.

The Wild Cards books, edited by George R. R. Martin launched in 1987, were a non-comic book-based science fiction series that dealt with super-powered heroes.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Marvel and DC released novels based on important stories from their comics, such as The Death of Superman and the year-long Batman: No Man’s Land.

John Ridley's 'Those Who Walk In Darkness' is about the special police teams that have to deal with super beings in the modern world.

Robert Mayer's 1977 Superfolks tells of a retired hero who has married and moved to the suburbs being drawn back into action.

Michael Bishop's 1992 novel Count Geiger's Blues has pop culture-hating critic Xavier Thaxton plunging into a pool of toxic waste, whereupon he transforms into a costumed superhero and gains an allergy to High Art.

Two anthologies of creator-owned superhero tales were released in conjunction with the Silver Age Sentinels role-playing game. 2003's Path of the Just featured an introduction by Denny O'Neil and stories by John Ostrander and Steven Grant. 2004's Path of the Bold had an introduction by Elliot S! Maggin and stories by Robert Weinberg and John Kovalic. Both anthologies were edited by James Lowder.

Computer games

While many popular superheroes have been featured in licensed computer games, up until recently there have been few that have revolved around heroes created specifically for the game. This has changed due to two popular franchises: The Silver Age-inspired Freedom Force (2002) and City of Heroes (2004), a Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game, both of which allow players to create their own superheroes.

Notes

- While "superhero" has been jointly trademarked by DC Comics and Marvel Comics, it is the more common usage. However, as an attempt to avoid the trademark, super-hero with a hyphen is sometimes used as a generic spelling that covers all such heroes, not simply those owned by DC or Marvel.

See also

- Anti-hero

- Evil genius

- Supervillain

- List of powers in superhero fiction

- List of superheroes

- List of anthropomorphic animal superheroes

- List of superhero teams and groups

- Elseworlds/What If - a popular type of superhero story

- Superhero and supervillain hideouts and bases

- Superhero Chronology

- Category: Real-life Superheroes

- List of actors who have played superheroes

External links

- Superhero Database Growing the biggest database of Superheroes

- Duke University exhibit on the development of superheroes

- Modernism and the Birth of the American Superhero, an article by Robert Emmons, Jr.

- Guardians of the North! a virtual museum tour through the history of Canadian superheroes, hosted by the National Library and Archives of Canada.

- The World's Worst Super-Heroes Extravaganza! on The 7th Level

- International Superheroes, an index of superheroes from around the world.