Acupuncture: Difference between revisions

link for human anatomy |

there are several problems with this source and the edits related to this |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

Ideas of what constitutes “health” and “healing” sometimes differ from concepts used in scientific, [[evidence based medicine]]. Acupuncture was developed prior to the science of [[human anatomy]] and the [[cell theory]] upon which the science of [[biology]] is based. Disease is believed to be caused by an imbalance of [[yin and yang]] (a [[metaphysical]] balance) caused by a "blockage" or "stagnation" of [[mystical]] "energy" (known as [[qi]]), not by infectious agents; qi "energy" is not recognized as existing in the science of [[physics]]. Location of meridians is based on the number of rivers flowing through an ancient Chinese empire, and the location of acupuncture points on the meridians is based on the number of days in the year,<ref name="Matuk2006" /> and do not correspond to any [[human anatomy|anatomical structure]]. No force corresponding to qi (or yin and yang) has been found in the sciences of [[physics]] or [[human physiology]].<ref name="Matuk2006" /><ref name=Mann>[[Felix Mann]], quoted by Matthew Bauer in ''[http://www.chinesemedicinetimes.com/section.php?xSec=122 Chinese Medicine Times]'', vol 1 issue 4, p. 31, August 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"</ref><ref name = NIH-1997consensus/><ref name = "TorT52" /><ref name="Ahn2008" /> |

Ideas of what constitutes “health” and “healing” sometimes differ from concepts used in scientific, [[evidence based medicine]]. Acupuncture was developed prior to the science of [[human anatomy]] and the [[cell theory]] upon which the science of [[biology]] is based. Disease is believed to be caused by an imbalance of [[yin and yang]] (a [[metaphysical]] balance) caused by a "blockage" or "stagnation" of [[mystical]] "energy" (known as [[qi]]), not by infectious agents; qi "energy" is not recognized as existing in the science of [[physics]]. Location of meridians is based on the number of rivers flowing through an ancient Chinese empire, and the location of acupuncture points on the meridians is based on the number of days in the year,<ref name="Matuk2006" /> and do not correspond to any [[human anatomy|anatomical structure]]. No force corresponding to qi (or yin and yang) has been found in the sciences of [[physics]] or [[human physiology]].<ref name="Matuk2006" /><ref name=Mann>[[Felix Mann]], quoted by Matthew Bauer in ''[http://www.chinesemedicinetimes.com/section.php?xSec=122 Chinese Medicine Times]'', vol 1 issue 4, p. 31, August 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"</ref><ref name = NIH-1997consensus/><ref name = "TorT52" /><ref name="Ahn2008" /> |

||

Evidence may support the use of acupuncture to control some types of [[nausea]]<ref name="pmid15266478"/> and [[pain]],<ref name="Cochrane back 2005"/> but evidence for the treatment of other conditions is equivocal,<ref name="pmid17265547"/> and several [[Review journal|review articles]] discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture have concluded it is possible to explain through the [[placebo effect]].<ref name = Madsen2009>{{cite doi | 10.1136/bmj.a3115 }}</ref><ref name="Ernst_2006-02">{{cite pmid | 16420542 }}</ref> [[Publication bias]] is a significant concern when evaluating the literature. Other claims of efficacy have not been tested. Reports from the US [[National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine]] In America, (NCCAM), the [[American Medical Association]] (AMA) and various US government reports have studied and commented on the efficacy (or lack thereof) of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe only when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles.<ref name="NIH-1997consensus">{{cite web |author=NIH Consensus Development Program |title=Acupuncture --Consensus Development Conference Statement |url=http://consensus.nih.gov/1997/1997Acupuncture107html.htm |date=November 3–5, 1997 |publisher= [[National Institutes of Health]] |accessdate=2007-07-17}}</ref><ref name="NCCAM2006-Acupuncture">{{cite web |title=Acupuncture |url=http://nccam.nih.gov/health/acupuncture/ |publisher=US [[National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine]]|year=2006 |accessdate=2006-03-02}}</ref><ref name="pmid12801494">{{cite pmid | 12801494 }}</ref><ref name="cite pmid | 12564354">{{cite pmid | 12564354 }}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===Antiquity=== |

===Antiquity=== |

||

Revision as of 17:02, 4 February 2011

| This article is part of a series on |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

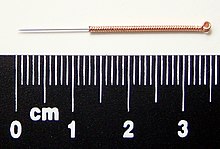

Acupuncture is an alternative medicine that treats patients by insertion and manipulation of needles in the body. Its practitioners variously claim that it relieves pain, treats infertility, treats disease, prevents disease, promotes general health, or can be used for therapeutic purposes.[1] Acupuncture's effectiveness for other than psychological effects is denied by the science based medicine community. Acupuncture typically incorporates traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) as an integral part of its practice and theory. The term “acupuncture” is sometimes used to refer to insertion of needles at points other than traditional ones, or to applying an electric current to needles in acupuncture points.[2][3] Acupunture dates back to prehistoric times, with written records from the second century BCE.[4] Different variations of acupuncture are practiced and taught throughout the world.

Ideas of what constitutes “health” and “healing” sometimes differ from concepts used in scientific, evidence based medicine. Acupuncture was developed prior to the science of human anatomy and the cell theory upon which the science of biology is based. Disease is believed to be caused by an imbalance of yin and yang (a metaphysical balance) caused by a "blockage" or "stagnation" of mystical "energy" (known as qi), not by infectious agents; qi "energy" is not recognized as existing in the science of physics. Location of meridians is based on the number of rivers flowing through an ancient Chinese empire, and the location of acupuncture points on the meridians is based on the number of days in the year,[5] and do not correspond to any anatomical structure. No force corresponding to qi (or yin and yang) has been found in the sciences of physics or human physiology.[5][6][7][8][9]

Evidence may support the use of acupuncture to control some types of nausea[10] and pain,[11] but evidence for the treatment of other conditions is equivocal,[12] and several review articles discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture have concluded it is possible to explain through the placebo effect.[13][14] Publication bias is a significant concern when evaluating the literature. Other claims of efficacy have not been tested. Reports from the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine In America, (NCCAM), the American Medical Association (AMA) and various US government reports have studied and commented on the efficacy (or lack thereof) of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe only when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles.[7][15][16][17]

History

Antiquity

The earliest written record of acupuncture is the Chinese text Shiji (史記, English: Records of the Grand Historian) with elaboration of its history in the 2nd century BCE medical text Huangdi Neijing (黃帝內經, English: Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon).[4]

Acupuncture's origins in China are uncertain. One explanation is that some soldiers wounded in battle by arrows were believed to have been cured of chronic afflictions that were otherwise untreated,[18] and there are variations on this idea.[19] In China, the practice of acupuncture can perhaps be traced as far back as the Stone Age, with the Bian shi, or sharpened stones.[20] In 1963 a bian stone was found in Duolun County, Inner Mongolia, China pushing the origins of acupuncture into the Neolithic age.[21] Hieroglyphs and pictographs have been found dating from the Shang Dynasty (1600-1100 BCE) which suggest that acupuncture was practiced along with moxibustion.[22]

Despite improvements in metallurgy over centuries, it was not until the 2nd century BCE during the Han Dynasty that stone and bone needles were replaced with metal.[21] The earliest records of acupuncture is in the Shiji (史記, in English, Records of the Grand Historian) with references in later medical texts that are equivocal, but could be interpreted as discussing acupuncture. The earliest Chinese medical text to describe acupuncture is the Huangdi Neijing, the legendary Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine (History of Acupuncture) which was compiled around 305–204 BC.[4]

The Huangdi Neijing does not distinguish between acupuncture and moxibustion and gives the same indication for both treatments. The Mawangdui texts, which also date from the 2nd century BC (though antedating both the Shiji and Huangdi Neijing), mention the use of pointed stones to open abscesses, and moxibustion but not acupuncture. However, by the 2nd century BCE, acupuncture replaced moxibustion as the primary treatment of systemic conditions.[4]

In Europe, examinations of the 5,000-year-old mummified body of Ötzi the Iceman have identified 15 groups of tattoos on his body, some of which are located on what are now seen as contemporary acupuncture points. This has been cited as evidence that practices similar to acupuncture may have been practiced elsewhere in Eurasia during the early Bronze Age.[23]

Middle history

Acupuncture spread from China to Korea, Japan and Vietnam and elsewhere in East Asia.

Around ninety works on acupuncture were written in China between the Han Dynasty and the Song Dynasty, and the Emperor Renzong of Song, in 1023, ordered the production of a bronze statuette depicting the meridians and acupuncture points then in use. However, after the end of the Song Dynasty, acupuncture and its practitioners began to be seen as a technical rather than scholarly profession. It became more rare in the succeeding centuries, supplanted by medications and became associated with the less prestigious practices of shamanism, midwifery and moxibustion.[24]

Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century were among the first to bring reports of acupuncture to the West.[25] Jacob de Bondt, a Danish surgeon travelling in Asia, described the practice in both Japan and Java. However, in China itself the practice was increasingly associated with the lower-classes and illiterate practitioners.[26]

The first European text on acupuncture was written by Willem ten Rhijne, a Dutch physician who studied the practice for two years in Japan. It consisted of an essay in a 1683 medical text on arthritis; Europeans were also at the time becoming more interested in moxibustion, which ten Rhijne also wrote about.[27] In 1757 the physician Xu Daqun described the further decline of acupuncture, saying it was a lost art, with few experts to instruct; its decline was attributed in part to the popularity of prescriptions and medications, as well as its association with the lower classes.[28]

In 1822, an edict from the Chinese Emperor banned the practice and teaching of acupuncture within the Imperial Academy of Medicine outright, as unfit for practice by gentlemen-scholars. At this point, acupuncture was still cited in Europe with both skepticism and praise, with little study and only a small amount of experimentation.[29]

Modern era

In the early years after the Chinese Civil War, Chinese Communist Party leaders ridiculed traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture, as superstitious, irrational and backward, claiming that it conflicted with the Party's dedication to science as the way of progress. Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong later reversed this position, saying that "Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house and efforts should be made to explore them and raise them to a higher level."[30]

Acupuncture gained attention in the United States when President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972. During one part of the visit, the delegation was shown a patient undergoing major surgery while fully awake, ostensibly receiving acupuncture rather than anesthesia. Later it was found that the patients selected for the surgery had both a high pain tolerance and received heavy indoctrination before the operation; these demonstration cases were also frequently receiving morphine surreptitiously through an intravenous drip that observers were told contained only fluids and nutrients.[31]

The greatest exposure in the West came when New York Times reporter James Reston, who accompanied Nixon during the visit, received acupuncture in China for post-operative pain after undergoing an emergency appendectomy under standard anesthesia. Reston believed he had pain from the acupuncture and wrote it in The New York Times.[32] In 1973 the American Internal Revenue Service allowed acupuncture to be deducted as a medical expense.[33]

In 2006, a BBC documentary Alternative Medicine filmed a patient undergoing open heart surgery allegedly under acupuncture-induced anaesthesia. It was later revealed that the patient had been given a cocktail of weak anaesthetics that in combination could have a much more powerful effect. The program was also criticised for its fanciful interpretation of the results of a brain scanning experiment.[34][35][36]

Acupuncture anesthesia for surgery has fallen out of favor with scientifically trained surgeons in China. A delegation of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal reported in 1995: We were not shown acupuncture anesthesia for surgery, this apparently having fallen out of favor with scientifically trained surgeons. Dr. Han, for instance, had been emphatic that he and his colleagues see acupuncture only as an analgesic (pain reducer), not an anesthetic (an agent that blocks all conscious sensations).[31]

Traditional theory

Traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is based on a pre-scientific paradigm of medicine that developed over several thousand years and involves concepts that have no counterpart within contemporary medicine.[7] The zang systems are associated with the solid, yin organs such as the liver while the fu systems are associated with the hollow yang organs such as the intestines. Health is explained as a state of balance between the yin and yang, with disease ascribed to either of these forces being unbalanced, blocked or stagnant.

Acupuncture points and meridians

| Flow of qi through the meridians | ||

| Zang-fu | Aspect | Hours |

| Lung | taiyin | 0300-0500 |

| Large Intestine | yangming | 0500-0700 |

| Stomach | yangming | 0700-0900 |

| Spleen | taiyin | 0900-1100 |

| Heart | shaoyin | 1100–1300 |

| Small Intestine | taiyang | 1300–1500 |

| Bladder | taiyang | 1500–1700 |

| Kidney | shaoyin | 1700–1900 |

| Pericardium | jueyin | 1900–2100 |

| San Jiao | shaoyang | 2100–2300 |

| Gallbladder | shaoyang | 2300-0100 |

| Liver | jueyin | 0100-0300 |

| Lung (repeats cycle) | ||

Acupuncture points are located based on a belief that the body is related to the number of rivers flowing toward the an ancient Cinese kingdom (believed to be exactly 12), and the number of days in the year (believed to be exactly 365).[5] "It is because of the twelve Primary channels that people live, that disease is formed, that people are treated and disease arises." [(Spiritual Axis, chapter 12)]. Channel theory reflects the limitations in the level of scientific development at the time of its formation, and is therefore tainted with the philosophical idealism and metaphysics of its day. That which has continuing clinical value needs to be reexamined through practice and research to determine its true nature.[37]

Traditional diagnosis

The acupuncturist decides which points to treat by observing and questioning the patient in order to make a diagnosis according to the tradition which he or she utilizes. In TCM, there are four diagnostic methods: inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation.[38]

- Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge.

- Auscultation and olfaction refer, respectively, to listening for particular sounds (such as wheezing) and attending to body odor.

- Inquiring focuses on the "seven inquiries", which are: chills and fever; perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination; pain; sleep; and menses and leukorrhea.

- Palpation includes feeling the body for tender "ashi" points, and palpation of the left and right radial pulses at two levels of pressure (superficial and deep) and three positions Cun, Guan, Chi (immediately proximal to the wrist crease, and one and two fingers' breadth proximally, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring fingers).

Tongue and pulse diagnosis and acupuncture treatment

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in traditional Chinese medicine. The surface of the tongue is believed to contain a map of the entire body, and is used to determine acupuncture points to manipulate. For example, teeth marks on one part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the heart, while teeth marks on another part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the liver.[39]

Pregnancy diagnosis and acupuncture to treat infertility

Acupuncture practitioners believe it can be used to treat infertility, and “both pregnancy and the sex of a child can be diagnosed from the pulses by a skilled practitioner”, as part of an overall reproductive technology.[40]

Traditional Chinese medicine perspective

Classically, in clinical practice, acupuncture treatment is typically highly individualized and based on philosophical constructs as well as subjective and intuitive impressions, and not on controlled scientific research.[41]

Clinical practice

Warming an acupuncture point, typically by moxibustion (burning or heating the skin at acupuncture points with a combination of herbs, primarily mugwort), is a different treatment than acupuncture itself and is often, but not exclusively, used as a supplemental treatment.[citation needed]

Indications according to acupuncturists in the West

The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture (2004) states: "In the United States, acupuncture has its greatest success and acceptance in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain."[42] They say that acupuncture may be considered as a complementary therapy for the conditions in the list below, noting: "Most of these indications are supported by textbooks or at least 1 journal article. However, definitive conclusions based on research findings are rare because the state of acupuncture research is poor but improving."[42] For example, drug detoxification is suggested[43] but evidence is poor.[44][45][46]

Scientific basis and research on efficacy

Acupuncture has been the subject of active scientific research both in regard to its basis and therapeutic effectiveness since the late 20th century, but it remains controversial among medical researchers and clinicians.[12] Research on acupuncture points and meridians has not demonstrated their existence or properties.[47] Clinical assessment of acupuncture treatments, due to its invasive and easily detected nature, makes it difficult to use proper scientific controls for placebo effects.[7][12][48][49][50]

Evidence supports the use of acupuncture to control some types of nausea[10] and pain[11] but evidence for the treatment of other conditions is equivocal[12] and several review articles discussing the effectiveness of acupuncture have concluded it is possible to explain through the placebo effect.[13][14]

The World Health Organization[51] and the United States' National Institutes of Health (NIH)[7] have stated that acupuncture can be effective in the treatment of neurological conditions and pain, though these statements have been criticized for bias and a reliance on studies that used poor methodology.[52][53] Reports from the USA's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), the American Medical Association (AMA) and various USA government reports have studied and commented on the efficacy (or lack thereof) of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles, and that further research is needed.[7][15][16][17]

Criticism

The National Council Against Health Fraud stated in 1990 that acupuncture’s “theory and practice are based on primitive and fanciful concepts of health and disease that bear no relationship to present scientific knowledge.”[54] In 1993 neurologist Arthur Taub called acupuncture “nonsense with needles.”[55] Physicist John P. Jackson,[56] Steven Salzberg, director of the Center for Bioinformatics and Computational Biology and professor at the University of Maryland,[57] Yale University professor of neurology, and founder and executive editor of Science Based Medicine, Steven Novella,[58] and Wallace I. Sampson, clinical professor emeritus of medicine at Stanford University and editor-in-chief at the Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, have all characterized acupuncture as pseudoscience.[59]

According to the 1997 NIH consensus statement on acupuncture:

Despite considerable efforts to understand the anatomy and physiology of the "acupuncture points", the definition and characterization of these points remains controversial. Even more elusive is the basis of some of the key traditional Eastern medical concepts such as the circulation of Qi, the meridian system, and the five phases theory, which are difficult to reconcile with contemporary biomedical information but continue to play an important role in the evaluation of patients and the formulation of treatment in acupuncture.[7]

Qi, acupuncture points and meridians

Acupuncture points are located based on what historian of science Camilla Matuk calls "mystical numerical associations", in that "12 vessels circulating blood and air corresponding to the 12 rivers flowing toward the Central Kindgom; and 365 parts of the body, one for each day of the year".[5] No research has established any consistent anatomical structure or function for either acupuncture points or meridians. The nervous system has been evaluated for a relationship to acupuncture points, but no structures have been clearly linked to them. Controversial studies using nuclear imaging have suggested that tracers may be used to follow meridians and are not related to veins or lymphatic tissues, but the interpretation of these results is unclear. The electrical resistance of acupuncture points and meridians have also been studied, with conflicting results.[9]

The meridians are part of the controversy in the efforts to reconcile acupuncture with conventional medicine. The National Institutes of Health 1997 consensus development statement on acupuncture stated that acupuncture points, Qi, the meridian system and related theories play an important role in the use of acupuncture, but are difficult to relate to a contemporary understanding of the body.[7] Chinese medicine forbade dissection, and as a result the understanding of how the body functioned was based on a system that related to the world around the body rather than its internal structures. The 365 "divisions" of the body were based on the number of days in a year, and the twelve meridians proposed in the TCM system are thought to be based on the twelve major rivers that run through China.[5]

These ancient traditions of Qi and meridians have no counterpart in modern studies of chemistry, biology and physics and to date scientists have been unable to find evidence that supports their existence.[8][9]

Acupuncturist Felix Mann, who was the author of the first comprehensive English language acupuncture textbook Acupuncture: The Ancient Chinese Art of Healing has stated that "The traditional acupuncture points are no more real than the black spots a drunkard sees in front of his eyes" and compared the meridians to the meridians of longitude used in geography - an imaginary human construct.[60] Mann attempted to join up his medical knowledge with that of Chinese theory. In spite of his protestations about the theory, he was fascinated by it and trained many people in the west with the parts of it he borrowed. He also wrote many books on this subject. His legacy is that there is now a college in London and a system of needling that is known as "Medical Acupuncture". Today this college trains doctors and western medical professionals only. Reviewers Leonid Kalichman and Simon Vulfsons have described the use of dry needling of myofascial trigger points as an effective and low risk treatment modality.[61] A systematic review of acupuncture for pain found that there was no difference between inserting needles into "true" acupuncture on traditional acupuncture points versus "placebo" points not associated with any TCM acupuncture points or meridians. The review concluded that "A small analgesic effect of acupuncture was found, which seems to lack clinical relevance and cannot be clearly distinguished from bias. Whether needling at acupuncture points, or at any site, reduces pain independently of the psychological impact of the treatment ritual is unclear."[13]

A report for CSICOP on pseudoscience in China written by Wallace Sampson and Barry Beyerstein said:

A few Chinese scientists we met maintained that although Qi is merely a metaphor, it is still a useful physiological abstraction (e.g., that the related concepts of Yin and Yang parallel modern scientific notions of endocrinologic [sic] and metabolic feedback mechanisms). They see this as a useful way to unite Eastern and Western medicine. Their more hard-nosed colleagues quietly dismissed Qi as only a philosophy, bearing no tangible relationship to modern physiology and medicine.[62]

Possible neural mechanism of action

Acupuncture and sham acupunture might poduce psychological pain and nausea relief, but this may be a result of the painful nature of insertion of needles for some people, and "it is well established that painful stimulation inhibits pain"; this has been proposed as a physiological basis of acupuncture analgesia."Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).[14] Publication bias is a significant concern when evaluating the literature. Other claims of efficacy have not been tested. Reports from the US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), the American Medical Association (AMA) and various US government reports have studied and commented on the efficacy (or lack thereof) of acupuncture. There is general agreement that acupuncture is safe when administered by well-trained practitioners using sterile needles.[7][15][16][17] The neural mechanisms underlying minute pain relief from insertion of needles are unknown, but it has been suggested that it may involve recruitment of the body's own pain reduction system, and an increased release of endorphins, serotonin, norepinephrine, or GABA.[63]

Efficacy study design

One of the major challenges in acupuncture research is in the design of an appropriate placebo control group.[48] In trials of new drugs, double blinding is the accepted standard, but since acupuncture is a procedure rather than a pill, it is difficult to design studies in which both the acupuncturist and patient are blinded as to the treatment being given. The same problem arises in double-blinding procedures used in biomedicine, including virtually all surgical procedures, dentistry, physical therapy, etc. As the Institute of Medicine states: "Controlled trials of surgical procedures have been done less frequently than studies of medications because it is much more difficult to standardize the process of surgery. Surgery depends to some degree on the skills and training of the surgeon and the specific environment and support team available to the surgeon. A surgical procedure in the hands of a highly skilled, experienced surgeon is different from the same procedure in the hands of an inexperienced and unskilled surgeon... For many CAM modalities, it is similarly difficult to separate the effectiveness of the treatment from the effectiveness of the person providing the treatment."[50]: 126 Acupuncture itself is also a very strong placebo, and can provoke extremely high expectations from patients and test subjects; this is particularly problematic for health problems like chronic low back pain, where conventional treatment is often relatively ineffective and may have been unsuccessfully used in the past. In situations like these, it may be inappropriate to consider "conventional care" a proper control intervention for acupuncture since patient expectations for conventional care are quite low.[64]

Blinding of the practitioner in acupuncture remains challenging. One proposed solution to blinding patients has been the development of "sham acupuncture", i.e., needling performed superficially or at non-acupuncture sites. Controversy remains over whether, and under what conditions, sham acupuncture may function as a true placebo, particularly in studies on pain, in which insertion of needles anywhere near painful regions may elicit a beneficial response.[7][49] A review in 2007 noted several issues confounding sham acupuncture: "Weak physiologic activity of superficial or sham needle penetration is suggested by several lines of research, including RCTs showing larger effects of a superficial needle penetrating acupuncture than those of a nonpenetrating sham control, positron emission tomography research indicating that sham acupuncture can stimulate regions of the brain associated with natural opiate production, and animal studies showing that sham needle insertion can have nonspecific analgesic effects through a postulated mechanism of “diffuse noxious inhibitory control”. Indeed, superficial needle penetration is a common technique in many authentic traditional Japanese acupuncture styles."[65]

An analysis of 13 studies of pain treatment with acupuncture, published in January 2009 in the journal BMJ, concluded there was little difference in the effect of real, sham and no acupuncture.[13]

Evidence-based medicine

There is scientific agreement that an evidence-based medicine (EBM) framework should be used to assess health outcomes and that systematic reviews with strict protocols are essential. Organizations such as the Cochrane Collaboration and Bandolier publish such reviews. In practice, EBM is "about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence".[66][67] Scientific disagreement over multiple aspects of acupuncture research is not uncommon.[68]

The development of the evidence base for acupuncture was summarized in a review by researcher Edzard Ernst and colleagues in 2007. They compared systematic reviews conducted (with similar methodology) in 2000 and 2005: "The effectiveness of acupuncture remains a controversial issue. ... The results indicate that the evidence base has increased for 13 of the 26 conditions included in this comparison. For 7 indications it has become more positive (i.e. favoring acupuncture) and for 6 it had changed in the opposite direction. It is concluded, that acupuncture research is active. The emerging clinical evidence seems to imply that acupuncture is effective for some but not all conditions."[12]

For acute low back pain there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against either acupuncture or dry needling, though for chronic low back pain acupuncture is more effective than sham treatment but no more effective than conventional and alternative treatments for short-term pain relief and improving function. However, when combined with other conventional therapies, the combination is slightly better than conventional therapy alone.[11][69] A review for the American Pain Society/American College of Physicians found fair evidence that acupuncture is effective for chronic low back pain.[70] Conducting research on low back pain is unusually problematic since most patients have experienced "conventional care" - which is itself relatively ineffective - and have low expectations for it. As such, conventional care groups may not be an adequate scientific control and may even lead to nocebo effects that can further inflate of the apparent effectiveness of acupuncture.[64]

There are both positive[71] and negative[72] reviews regarding the effectiveness of acupuncture when combined with in vitro fertilisation.

A Cochrane Review concluded that acupuncture was effective in reducing the risk of post-operative nausea and vomiting with minimal side effects, though it was less than or equal to the effectiveness of preventive antiemetic medications.[10] A 2006 review initially concluded that acupuncture appeared to be more effective than antiemetic drugs, but the authors subsequently retracted this conclusion due to a publication bias in Asian countries that had skewed their results; their ultimate conclusion was in line with the Cochrane Review - acupuncture was approximately equal to, but not better than preventive antiemetic drugs in treating nausea.[73] Another Cochrane Review concluded that electroacupuncture can be helpful in the treatment of vomiting after the start of chemotherapy, but more trials were needed to test their effectiveness versus modern antivomiting medication.[74]

There is moderate evidence that for neck pain, acupuncture is more likely to be effective than sham treatment and offers short-term improvement compared to those on a waiting list.[75]

There is evidence to support the use of acupuncture to treat headaches that are idiopathic, though the evidence is not conclusive and more studies need to be conducted.[76] Several trials have indicated that migraine patients benefit from acupuncture, although the correct placement of needles seems to be less relevant than is usually thought by acupuncturists. Overall in these trials acupuncture was associated with slightly better outcomes and fewer adverse effects than prophylactic drug treatment.[77]

There is conflicting evidence that acupuncture may be useful for osteoarthritis of the knee, with both positive,[78][79] and negative[65] results. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International released a set of consensus recommendations in 2008 that concluded acupuncture may be useful for treating the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee.[80]

A systematic review of the best five randomized controlled trials available concluded there was insufficient evidence to support the use of acupuncture in the treatment of the symptoms of fibromyalgia.[81]

For the following conditions, the Cochrane Collaboration has concluded there is insufficient evidence to determine whether acupuncture is beneficial, often because of the paucity and poor quality of the research, and that further research is needed: chronic asthma,[82] Bell's palsy,[83] cocaine dependence,[84] depression,[85] rimary dysmenorrhoea (incorporating TENS,[86] epilepsy,[87] glaucoma,[88] insomnia,[89] irritable bowel syndrome,[90] induction of childbirth,[91] rheumatoid arthritis,[92] shoulder pain,[93] schizophrenia,[94] smoking cessation,[95] acute stroke,[96] stroke rehabilitation,[97] tennis elbow,[98] and vascular dementia.[99]

Positive results from some studies on the efficacy of acupuncture may be as a result of poorly designed studies or publication bias.[100][101] Edzard Ernst and Simon Singh state that as the quality of experimental tests of acupuncture have increased over the course of several decades (through better blinding, the use of sham needling as a form of placebo control, etc.) the results have demonstrated less and less evidence that acupuncture is better than placebo at treating most conditions.[102]

Neuroimaging studies

A 2005 literature review examining the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography to study changes in brain activity caused by acupuncture[103] concluded that neuroimaging data to date show some promise for being able to distinguish the cortical effects of expectation, placebo, and real acupuncture. The studies reviewed were mostly small and pain-related, and more research is needed to determine the specificity of neural substrate activation in non-painful indications.

Medical organizations

Citing research that had accumulated since 1993, the American Medical Association (AMA) Council on Scientific Affairs produced a report in 1997, which stated that there was insufficient evidence to support acupuncture's effectiveness in treating disease, and highlighted the need for further research. That report also included a policy statement that cited the lack of evidence, and sometimes evidence against, the safety and efficacy of alternative medicine interventions, including acupuncture and called for "Well-designed, stringently controlled research...to evaluate the efficacy of alternative therapies."[104]

Also in 1997, the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) issued a consensus statement on acupuncture that concluded that despite research on acupuncture being difficult to conduct, there was sufficient evidence to encourage further study and expand its use.[7] The consensus statement and conference that produced it were criticized by Wallace Sampson, writing for an affiliated publication of Quackwatch who stated the meeting was chaired by a strong proponent of acupuncture and failed to include speakers who had obtained negative results on studies of acupuncture. Sampson also stated he believed the report showed evidence of pseudoscientific reasoning.[105] In 2006 the NIH's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine stated that it continued to abide by the recommendations of the 1997 NIH consensus statement, even if research is still unable to explain its mechanism.[15]

In 2003 the World Health Organization's Department of Essential Drugs and Medicine Policy produced a report on acupuncture. The report was drafted, revised and updated by Zhu-Fan Xie, the Director for the Institute of Integrated Medicines of Beijing Medical University. It contained, based on research results available in early 1999, a list of diseases, symptoms or conditions for which it was believed acupuncture had been demonstrated as an effective treatment, as well as a second list of conditions that were possibly able to be treated with acupuncture. Noting the difficulties of conducting controlled research and the debate on how to best conduct research on acupuncture, the report described itself as "...intended to facilitate research on and the evaluation and application of acupuncture. It is hoped that it will provide a useful resource for researchers, health care providers, national health authorities and the general public."[51] The coordinator for the team that produced the report, Xiaorui Zhang, stated that the report was designed to facilitate research on acupuncture, not recommend treatment for specific diseases.[53] The report was controversial; critics assailed it as being problematic since, in spite of the disclaimer, supporters used it to claim that the WHO endorsed acupuncture and other alternative medicine practices that were either pseudoscientific or lacking sufficient evidence-basis. Medical scientists expressed concern that the evidence supporting acupuncture outlined in the report was weak, and Willem Betz of SKEPP (Studie Kring voor Kritische Evaluatie van Pseudowetenschap en het Paranormale, the Study Circle for the Critical Evaluation of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal) said that the report was evidence that the "WHO has been infiltrated by missionaries for alternative medicine".[53] The WHO 2005 report was also criticized in the 2008 book Trick or Treatment for, in addition to being produced by a panel that included no critics of acupuncture at all, containing two major errors - including too many results from low-quality clinical trials, and including a large number of trials originating in China where, probably due to publication bias, no negative trials have ever been produced. In contrast, studies originating in the West include a mixture of positive, negative and neutral results. Ernst and Singh, the authors of the book, described the report as "highly misleading", a "shoddy piece of work that was never rigorously scrutinized" and stated that the results of high-quality clinical trials do not support the use of acupuncture to treat anything but pain and nausea.[106]

The National Health Service of the United Kingdom states that there is "reasonably good evidence that acupuncture is an effective treatment" for nausea, vomiting, osteoarthritis of the knee and several types of pain but "because of disagreements over the way acupuncture trials should be carried out and over what their results mean, this evidence does not allow us to draw definite conclusions". The NHS states there is evidence against acupuncture being useful for rheumatoid arthritis, smoking cessation and weight loss, and inadequate evidence for most other conditions that acupuncture is used for.[68]

Safety

Because acupuncture needles penetrate the skin, many forms of acupuncture are invasive procedures, and therefore not without risk. Injuries are rare among patients treated by trained practitioners.[107][108] In most jurisdictions, needles are required by law to be sterile, disposable and used only once; in some places, needles may be reused if they are first resterilized, e.g. in an autoclave. When needles are contaminated, risk of bacterial or other blood-borne infection increases, as with re-use of any type of needle.[109]

Adverse events

Estimates of adverse event rates due to acupuncture range from 671[110] to 1,137 per 10,000 treatments, generally minor.[16] A 2010 systematic review found that acupuncture has been associated with a total of 86 deaths (that number being the sum of fatalities over all years surveyed), most commonly due to pneumothorax; with adequate training fatalities can be avoided.[111]

Other injury

Other risks of injury from the improper insertion of acupuncture needles include: Nerve injury, resulting from the accidental puncture of any nerve, Brain damage or stroke, which is possible with very deep needling at the base of the skull, [[Pneumothors/en/ab004131.html|accessdate=20 lung,[112] Kidney damage from deep needling in the low back, Haemopericardium, or puncture of the protective membrane surrounding the heart, which may occur with needling over a sternal foramen (a hole in the breastbone that occurs as the result of a congenital defect.),[113] Risk of terminating pregnancy with the use of certain acupuncture points that have been shown to stimulate the production of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and oxytocin, and with unsterilized needles and lack of infection control: transmission of infectious diseases.

The risk can be reduced through proper training of acupuncturists. Graduates of medical schools and (in the US) accredited acupuncture schools receive thorough instruction in proper technique so as to avoid these events.[114]

Omitting modern medical care

Receiving alternative medicine as a replacement for standard modern medical care could result in inadequate diagnosis or treatment of conditions for which modern medicine has a better treatment record.

Concern has also been expressed that unethical or naive practitioners may induce patients to exhaust financial resources by pursuing ineffective treatment.[115][116] Profession ethical codes set by accrediting organizations such as the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine require referrals to make "timely referrals to other health care professionals as may be appropriate."[117] In Canada, public health departments in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia regulate acupuncture.[118][119]

Legal and political status

Those who specialize in Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine are usually referred to as "licensed acupuncturists", or L.Ac.'s. The abbreviation "Dipl. Ac." stands for "Diplomate of Acupuncture" and signifies that the holder is board-certified by the NCCAOM.[120]

A poll of American doctors in 2005 showed that 59% believe acupuncture was at least somewhat effective for treatment of pain.[121] In 1996, the United States Food and Drug Administration changed the status of acupuncture needles from Class III to Class II medical devices, meaning that needles are regarded as safe and effective when used appropriately by licensed practitioners.[122][123] As of 2004, nearly 50% of Americans who were enrolled in employer health insurance plans were covered for acupuncture treatments.[124][125]

In Ontario, the practice of acupuncture is now regulated by the Traditional Chinese Medicine Act, 2006, S.O. 2006, chapter 27.[126] The government is in the process of establishing a college[127] whose mandate will be to oversee the implementation of policies and regulations relating to the profession.

In the United Kingdom, acupuncturists are not a regulated profession. The principle body for professional standards in traditional/lay acupuncture is the British Acupuncture Council,[128] The British Medical Acupuncture Society [129] is an inter-disciplinary professional body for regulated health professional using acupuncture as a modality and then there is the Acupuncture Association of Chartered Physiotherapists.[130]

In Australia traditional/lay acupuncture is not a regulated health profession. traditional/lay acupuncture or Chinese Medicine was not included in the National Health Regulation Law.[131] Acupuncture will not be recognised as profession in Australia but as a modality either within Chinese Medicine / traditional Asian healing systems or within the scope of practice of regulated health professions. The practice of acupuncture is governed by a range of state / territory laws relating to consumer protection and infection control. Victoria is the only state of Australia with an operational registration board.[132] Currently acupuncturists in New South Wales are bound by the guidelines in the Public Health (Skin Penetration) Regulation 2000,[133] which is enforced at local council level. Other states of Australia have their own skin penetration acts.

In New Zealand traditional/lay acupuncture is not a regulated health profession. Osteopaths have a scope of practice for Western Medical Acupuncture and Related Needling Techniques.[134] The state-owned Accident Compensation Corporation reimburses for acupuncture treatment by registered healthcare practitioners and some traditional/lay acupuncturists that belong to voluntary professional associations.[135]

Many other countries do not license acupuncturists or require them to be trained.

See also

References

- Barnes, LL (2005). Needles, herbs, gods, and ghosts: China, healing, and the West to 1848. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674018729.

- Cheng, X (1987). Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1st ed.). Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 7-119-00378-X.

- Singh, S (2008). Trick or treatment: The undeniable facts about alternative medicine. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393066616.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Free preview at Google Books - Stux, Gabriel (1988). Basics of Acupuncture. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 354053072x.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Footnotes

- ^ Novak, Patricia D.; Norman W. Dorland; Dorland, William A. N. (1995). Dorland's Pocket Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-5738-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de las Peñas, César Fernández; Arendt-Nielsen, Lars; Gerwin, Robert D (2010). Tension-type and cervicogenic headache: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Jones & Bartlett Learning. ISBN 9780763752835.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Robertson, Valma J; Robertson, Val; Low, John; Ward, Alex; Reed, Ann (2006). Electrotherapy explained: principles and practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780750688437.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Prioreschi, P (2004). A history of Medicine, Volume 2. Horatius Press. pp. 147–8. ISBN 1888456019.

- ^ a b c d e Camillia Matuk (2006). "Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration" (PDF). Journal of Biocommunication. 32 (1).

- ^ Felix Mann, quoted by Matthew Bauer in Chinese Medicine Times, vol 1 issue 4, p. 31, August 2006, "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? - Part One"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k NIH Consensus Development Program (November 3–5, 1997). "Acupuncture --Consensus Development Conference Statement". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2007-07-17.

- ^ a b Singh & Ernst, 2008, p. 52-3.

- ^ a b c Ahn, AC; Colbert, AP; Anderson, BJ; Martinsen, OG; Hammerschlag, R; Cina, S; Wayne, PM; Langevin, HM (2008). "Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: a systematic review". Bioelectromagnetics. 29 (4): 245–56. doi:10.1002/bem.20403. PMID 18240287.

- ^ a b c Lee A, Done ML (2004). "Stimulation of the wrist acupuncture point P6 for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (3): CD003281. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003281.pub2. PMID 15266478.

- ^ a b c Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC (2005). "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD001351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. PMID 15674876.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K. (2007). "Acupuncture: its evidence-base is changing". Am J Chin Med. 35 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1142/S0192415X07004588. PMID 17265547.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3115 , please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi= 10.1136/bmj.a3115instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16420542 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 16420542instead. - ^ a b c d "Acupuncture". US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006. Retrieved 2006-03-02. Cite error: The named reference "NCCAM2006-Acupuncture" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12801494 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 12801494instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12564354 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 12564354instead. - ^ Tiran, D (2000). Complementary therapies for pregnancy and childbirth. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 79. ISBN 0702023280.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ e.g. White, A (1999). Acupuncture: a scientific appraisal. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1. ISBN 0750641630.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Ma, K (1992). "The roots and development of Chinese acupuncture: from prehistory to early 20th century". Acupuncture in Medicine. 10 ((Suppl)): 92–9. doi:10.1136/aim.10.Suppl.92.

- ^ a b Chiu, M (1993). Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2. ISBN 0443042233.

- ^ Robson, T (2004). An Introduction to Complementary Medicine. Allen & Unwin. pp. 90. ISBN 1741140544.

- ^ Dofer, L; Moser, M; Bahr, F; Spindler, K; Egarter-Vigl, E; Giullén, S; Dohr, G; Kenner, T (1999). "A medical report from the stone age?" (pdf). The Lancet. 354 (9183): 1023–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)12242-0. PMID 10501382.

- ^ Barnes, 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Unschuld, Paul. Chinese Medicine, p. 94. 1998, Paradigm Publications

- ^ Barnes, 2005, p. 58-9.

- ^ Barnes, 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Barnes, 2005, p. 188.

- ^ Barnes, 2005, p. 308-9.

- ^ Crozier RC (1968). Traditional medicine in modern China: science, nationalism, and the tensions of cultural change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- ^ a b Beyerstein, BL (1996). "Traditional Medicine and Pseudoscience in China: A Report of the Second CSICOP Delegation (Part 1)". Skeptical Inquirer. 20 (4). Committee for Skeptical Inquiry.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Davidson JP (1999). The complete idiot's guide to managing stress. Indianapolis, Ind: Alpha Books. pp. 255. ISBN 0-02-862955-8.

- ^ Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 133. ISBN 0465041957.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Singh & Ernst, 2008, p. 49.

- ^ Simon Singh (2006-03-26). "A groundbreaking experiment ... or a sensationalised TV stunt?". The Guardian.

- ^ Simon Singh (14 February 2006). "Did we really witness the 'amazing power' of acupuncture?". Daily Telegraph.

- ^ O'Connor J & Bensky D (trans. & eds.) (1981). Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text. Seattle, Washington: Eastland Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-939616-00-9.

- ^ Cheng, 1987, chapter 12.

- ^ “Tongue Diagnosis in Chinese Medicine”, Giovanni Maciocia, Eastland Press; Revised edition (June 1995)

- ^ ” Chinese Medicine and Assisted Reproductive Technology for the Modern Couple”, Roger C. Hirsh, OMD, L.Ac., Acupuncture.com, [1]

- ^ Medical Acupuncture - Spring / Summer 2000- Volume 12 / Number 1

- ^ a b Braverman S (2004). "Medical Acupuncture Review: Safety, Efficacy, And Treatment Practices". Medical Acupuncture. 15 (3).

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12623739, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12623739instead. - ^ Jordan JB (2006). "Acupuncture treatment for opiate addiction: a systematic review". J Subst Abuse Treat. 30 (4): 309–14. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2006.02.005. PMID 16716845.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gates S, Smith LA, Foxcroft DR (2006). "Auricular acupuncture for cocaine dependence". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD005192. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005192.pub2. PMID 16437523.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bearn J, Swami A, Stewart D, Atnas C, Giotto L, Gossop M (2009). "Auricular acupuncture as an adjunct to opiate detoxification treatment: effects on withdrawal symptoms". J Subst Abuse Treat. 36 (3): 345–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.002. PMID 19004596.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Napadow V, Ahn A, Longhurst J; et al. (2008). "The status and future of acupuncture mechanism research". Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 14 (7): 861–9. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.SAR-3. PMID 18803495.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b White AR, Filshie J, Cummings TM (2001). "Clinical trials of acupuncture: consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding". Complement Ther Med. 9 (4): 237–245. doi:10.1054/ctim.2001.0489. PMID 12184353.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Johnson MI (2006). "The clinical effectiveness of acupuncture for pain relief—you can be certain of uncertainty". Acupunct Med. 24 (2): 71–9. doi:10.1136/aim.24.2.71. PMID 16783282.

- ^ a b Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public (2005). "Complementary and Alternative Medicine in the United States" (Document). National Academies Press.

{{cite document}}: Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ a b Zhu-Fan, X (2003). Zhang X (ed.). "Acupuncture: Review and Analysis of Reports on Controlled Clinical Trials". World Health Organization.

- ^ Singh & Ernst, 2008, p. 70-73.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, M (2005). "Critics slam draft WHO report on homoeopathy". The Lancet. 366 (9487): 705–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67159-0. PMID 16130229.

- ^ "Position Paper on Acupuncture". National Council Against Health Fraud. 1990. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ Arthur Taub (1993). Acupuncture: Nonsense with Needles.

- ^ John P. Jackson. "What is acupuncture?".

- ^ Steven Salzberg (2008). "Acupuncture infiltrates the University of Maryland and NEJM".

- ^ Steven Novella. "Acupuncture Pseudoscience in the New England Journal of Medicine".

- ^ Wallace I. Sampson. "Critique of the NIH Consensus Conference on Acupuncture".

- ^ Mann, Felix (2000). Reinventing acupuncture: a new concept of ancient medicine. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 14, 31. ISBN 0-7506-4857-0.

- ^ Kalichman L, Vulfsons S (2010 Sep-Oct). "Dry needling in the management of musculoskeletal pain". J Am Board Fam Med. 23 (5): 640–6. PMID 20823359.

Dry needling is a treatment modality that is minimally invasive, cheap, easy to learn with appropriate training, and carries a low risk. Its effectiveness has been confirmed in numerous studies and 2 comprehensive systematic reviews.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sampson, Wallace Sampson (1996). "Traditional Medicine and Pseudoscience in China: A Report of the Second CSICOP Delegation (Part 2)". Skeptical Inquirer. 20 (5). Retrieved 2009-09-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sun Y, Gan TJ, Dubose JW, Habib AS (2008). "Acupuncture and related techniques for postoperative pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Br J Anaesth. 101 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1093/bja/aen146. PMID 18522936.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19942631 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 19942631instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17577006 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 17577006instead. - ^ Sackett, David L (1996-01). "Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't". BMJ. 312: 71. PMID 17340682.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Vickers, AJ (2001). "Message to complementary and alternative medicine: evidence is a better friend than power" (pdf). BMC Complement Altern Med. 1 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-1-1. PMC 32159. PMID 11346455.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "Acupuncture: Evidence for its effectiveness". National Health Service. 2010-03-18. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ^ Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, Forys K, Ernst E (2005). "Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain" (PDF). Ann. Intern. Med. 142 (8): 651–63. PMID 15838072.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chou R, Huffman LH (2007). "Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline". Ann Intern Med. 147 (7): 492–504. doi:10.1001/archinte.147.3.492. PMID 17909210.

- ^ Manheimer E, Zhang G, Udoff L, Haramati A, Langenberg P, Berman BM, Bouter LM (2008). "Effects of acupuncture on rates of pregnancy and live birth among women undergoing in vitro fertilisation: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 336 (7643): 545–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39471.430451.BE. PMC 2265327. PMID 18258932.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ El-Toukhy, T; Sunkara, SK; Khairy, M; Dyer, R; Khalaf, Y; Coomarasamy, A (2008). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of acupuncture in in vitro fertilisation". BMJ. 115 (10): 1203–13. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01838.x. PMID 18652588.

- ^ Lee A, Copas JB, Henmi M, Gin T, Chung RC (2006). "Publication bias affected the estimate of postoperative nausea in an acupoint stimulation systematic review". J Clin Epidemiol. 59 (9): 980–3. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.003. PMID 16895822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ezzo, JM; Richardson, MA; Vickers, A; Allen, C; Dibble, SL; Issell, BF; Lao, L; Pearl, M; Ramirez, G (2006). "Acupuncture-point stimulation for chemotherapy-induced nausea or vomiting". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (2): CD002285. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002285.pub2. PMID 16625560.

- ^ Trinh K, Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith C, Wang E, Cameron I, Kay T (2007). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Spine. 32 (2): 236–43. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000252100.61002.d4. PMID 17224820.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Trinh K, Graham N, Gross A, Goldsmith C, Wang E, Cameron I, Kay T (2006). "Acupuncture for neck disorders". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD004870. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004870.pub3. PMID 16856065.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11279710, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11279710instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19160193, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19160193instead. - ^ White A, Foster NE, Cummings M, Barlas P (2007). "Acupuncture treatment for chronic knee pain: a systematic review". Rheumatology. 46 (3): 384–90. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel413. PMID 17215263.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Selfe TK, Taylor AG (2008 Jul-Sep). "Acupuncture and osteoarthritis of the knee: a review of randomized, controlled trials". Fam Community Health. 31 (3): 247–54. doi:10.1097/01.FCH.0000324482.78577.0f. PMC 2810544. PMID 18552606.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Zhang, W; Moskowitz, RW; Nuki, G; Abramson, S; Altman, RD; Arden, N; Bierma-Zeinstra, S; Brandt, KD; Croft, P (2008). "OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines" (pdf). Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 16 (2): 137–162. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013. PMID 18279766.

- ^ Mayhew E; Ernst E (2007). "Acupuncture for fibromyalgia—a systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 46 (5): 801–4. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kel406. PMID 17189243.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

McCarney, RW; Brinkhaus, B; Lasserson, TJ; Linde, K; McCarney, Robert W (2003). "Acupuncture for chronic asthma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003 (3): CD000008. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000008.pub2. PMID 14973944. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|first1=and|first=specified (help); More than one of|last1=and|last=specified (help) - ^ He, L; Zhou, MK; Zhou, D; Wu, B; Li, N; Kong, SY; Zhang, DP; Li, QF; Yang, J (2004). "Acupuncture for Bell's palsy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (4): CD002914. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002914.pub3. PMID 17943775. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Gates, S; Smith, LA; Foxcroft, DR; Gates, Simon (2006). "Auricular acupuncture for cocaine dependence". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (1): CD005192. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005192.pub2. PMID 16437523. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Smith, CA; Hay, PP; Smith, Caroline A (2004-03-17). "Acupuncture for depression". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004 (3): CD004046. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub2. PMID 15846693. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^

Proctor, ML; Smith, CA; Farquhar, CM; Stones, RW; Zhu, Xiaoshu; Brown, Julie; Zhu, Xiaoshu (2002

volume=2002). "Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002123. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002123. PMID 11869624. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Missing pipe in:|year=(help); line feed character in|year=at position 5 (help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Cheuk, DK; Wong, V; Cheuk, Daniel (2006). "Acupuncture for epilepsy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (2): CD005062. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005062.pub2. PMID 16625622. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Law, SK; Li, T; Law, Simon K (2007). "Acupuncture for glaucoma". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (4): CD006030. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006030.pub2. PMID 17943876. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Cheuk, DK; Yeung, WF; Chung, KF; Wong, V; Cheuk, Daniel KL (2007). "Acupuncture for insomnia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (3): CD005472. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005472.pub2. PMID 17636800. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ Lim, B; Manheimer, E; Lao, L; Ziea, E; Wisniewski, J; Liu, J; Berman, B; Manheimer, Eric (2006). "Acupuncture for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (4): CD005111. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005111.pub2. PMID 17054239. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Smith, CA; Crowther, CA; Smith, Caroline A (2004). "Acupuncture for induction of labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2004 (1): CD002962. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002962.pub2. PMID 14973999. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Casimiro, L; Barnsley, L; Brosseau, L; Milne, S; Robinson, VA; Tugwell, P; Wells, G; Casimiro, Lynn (2005). "Acupuncture and electroacupuncture for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (4): CD003788. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003788.pub2. PMID 16235342. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Green, S; Buchbinder, R; Hetrick, S; Green, Sally (2005). "Acupuncture for shoulder pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (2): CD005319. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005319. PMID 15846753. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Rathbone, J; Xia, J; Rathbone, John (2005). "Acupuncture for schizophrenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (4): CD005475. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005475. PMID 16235404. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ White, AR; Rampes, H; Campbell, JL; White, Adrian R (2006). "Acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (1): CD000009. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000009.pub2. PMID 16437420. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Zhang, SH; Liu, M; Asplund, K; Li, L; Liu, Ming (2005). "Acupuncture for acute stroke". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (2): CD003317. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003317.pub2. PMID 15846657. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Wu, HM; Tang, JL; Lin, XP; Lau, J; Leung, PC; Woo, J; Li, YP; Wu, Hong Mei (2006). "Acupuncture for stroke rehabilitation". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006 (3): CD004131. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004131.pub2. PMID 16856031. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Green, S; Buchbinder, R; Barnsley, L; Hall, S; White, M; Smidt, N; Assendelft, W; Green, Sally (2002). "Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2002 (1): CD003527. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003527. PMID 11869671. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Peng, WN; Zhao, H; Liu, ZS; Wang, S; Weina, Peng (2008). "Acupuncture for vascular dementia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 (2): CD004987. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004987.pub2. PMID 17443563. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ Tang JL, Zhan SY, Ernst E (1999). "Review of randomised controlled trials of traditional Chinese medicine". BMJ. 319 (7203): 160–1. PMC 28166. PMID 10406751.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R, Rees R (1998). "Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials". Control Clin Trials. 19 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00150-5. PMID 9551280.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Singh & Ernst, 2008, p. 79-82.

- ^ Lewith GT, White PJ, Pariente J (2005). "Investigating acupuncture using brain imaging techniques: the current state of play". Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine: eCAM. 2 (3): 315–9. doi:10.1093/ecam/neh110. PMC 1193550. PMID 16136210. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Report 12 of the Council on Scientific Affairs (A-97) – Alternative Medicine". American Medical Association. 1997. Retrieved 2009-10-07.

- ^ Sampson, W (2005-03-23). "Critique of the NIH Consensus Conference on Acupuncture". Quackwatch. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ Singh & Ernst, 2008, p. 277-8.

- ^ Lao L, Hamilton GR, Fu J, Berman BM (2003). "Is acupuncture safe? A systematic review of case reports". Alternative therapies in health and medicine. 9 (1): 72–83. PMID 12564354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Norheim AJ (1996). "Adverse effects of acupuncture: a study of the literature for the years 1981–1994". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine. 2 (2): 291–7. doi:10.1089/acm.1996.2.291. PMID 9395661.

- ^ http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/340/mar18_1/c1268

- ^ White, A; Hayhoe, S; Hart, A; Ernst, E (2001). "Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists". British Medical Journal. 323 (7311): 485–6. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7311.485. PMC 48133. PMID 11532840.

- ^ Ernst E (2010). "Deaths after acupuncture: A systematic review". The International Journal of Risk and Safety in Medicine. 22 (3): 131–136. doi:10.3233/JRS-2010-0503.

- ^ Leow TK (2001). "Pneumothorax Using Bladder 14". Medical Acupuncture. 16 (2).

- ^ Yekeler, Ensar; Tunaci, M; Tunaci, A; Dursun, M; Acunas, G. "Frequency of Sternal Variations and Anomalies Evaluated by MDCT". American Journal of Roentgenology. 186 (4): 956–60. doi:10.2214/AJR.04.1779. PMID 16554563. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Cheng, 1987.

- ^ Barret, S (2007-12-30). "Be Wary of Acupuncture, Qigong, and "Chinese Medicine"". Quackwatch. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Final Report, Report into Traditional Chinese Medicine" (pdf). Parliament of New South Wales. 2005-11-09. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "NCCAOM Code of Ethics" (pdf). National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ "Traditional Chinese Medicine Act, 2006". ServiceOntario. 2007-06-04. Retrieved 2010-11-03. [dead link]

- ^ "Health Professions Act: Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners and Acupuncturists Regulation". Queen’s Printer for British Columbia. 2008-10-15. Retrieved 2010-11-03.

- ^ NCCAOM

- ^ "More than half of the physicians (59%) believed that acupuncture can be effective to some extent." Physicians Divided on Impact of CAM on U.S. Health Care; Aromatherapy Fares Poorly; Acupuncture Touted. HCD Research, 9 September 2005. convenience links: Business Wire, 2005; AAMA, 2005. Link to internet archive version: Cumulative Report

- ^ Updates-June 1996 FDA Consumer

- ^ US FDA/CDRH: Premarket Approvals

- ^ Report: Insurance Coverage for Acupuncture on the Rise. Michael Devitt, Acupuncture Today, January, 2005, Vol. 06, Issue 01

- ^ Claxton, Gary (2004). The Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits 2004 Annual Survey (PDF). pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-87258-812-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Traditional Chinese Medicine Act, 2006, S.O. 2006, c. 27

- ^ "Welcome to the TC-CTCMPAO". Ctcmpao.on.ca. Retrieved 2009-09-02.

- ^ http://www.acupuncture.org.uk/index.php

- ^ http://www.medical-acupuncture.co.uk/

- ^ http://www.aacp.org.uk/

- ^ http://www.ahpra.gov.au/

- ^ Welcome to the Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria

- ^ "Health NSW" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.osteopathiccouncil.org.nz/scopes-of-practice.html

- ^ ACC Releases Guidelines for Acupuncture Treatment

Further reading

- Deadman, P (2007). A Manual of Acupuncture. Journal of Chinese Medicine Publications. ISBN 0951054651.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Jin, G (2006). Contemporary Medical Acupuncture - A Systems Approach (English). Springer. ISBN 7040192578.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Maciocia, G (1989). The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text for Acupuncturists and Herbalists (2nd ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0443039801.

External links

![]() Media related to Acupuncture at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acupuncture at Wikimedia Commons

![]() Quotations related to Traditional Chinese medicine at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Traditional Chinese medicine at Wikiquote

- Articles needing cleanup from June 2010

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from June 2010

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from June 2010

- Articles needing cleanup from May 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from May 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from May 2008

- Acupuncture

- Chinese inventions

- Energy therapies

- Alternative medicine