Anti-Romani sentiment: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

|||

| Line 498: | Line 498: | ||

==Antiziganism in popular culture== |

==Antiziganism in popular culture== |

||

* The [[European Center for Antiziganism Research]] officially filed a complaint against [[Sacha Baron Cohen]] — who plays [[Borat Sagdiyev|Borat]] in the eponymous [[mockumentary]] film ''[[Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan|Borat]]'' — for inciting violence and violating [[Germany]]'s anti-discrimination laws.<ref>[http://www.breitbart.com/news/2006/11/01/061101190142.n43n2q02.html Rights group files complaint against 'Borat' in Germany]{{dead link|date=May 2012}}</ref> One part of the [[Satire|satirical]] film, which purportedly portrays Borat's impoverished native village in [[Kazakhstan]], actually shows a Romani village in Romania. |

* The [[European Center for Antiziganism Research]] officially filed a complaint against [[Sacha Baron Cohen]] — who plays [[Borat Sagdiyev|Borat]] in the eponymous [[mockumentary]] film ''[[Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan|Borat]]'' — for inciting violence and violating [[Germany]]'s anti-discrimination laws.<ref>[http://www.breitbart.com/news/2006/11/01/061101190142.n43n2q02.html Rights group files complaint against 'Borat' in Germany]{{dead link|date=May 2012}}</ref> One part of the [[Satire|satirical]] film, which purportedly portrays Borat's impoverished native village in [[Kazakhstan]], actually shows a Romani village in Romania. Note that neither Mr. Cohen himself, his character, nor the plot bear any relation whatsoever to either Kazakhstan or Romania (or their people - be they Romani, Kazakh, Romanian, Russian, etc.), and the attribution of this generic "barbaric foreigner from an unpleasant backwards country" to specific cultures or locales was widely seen as inflammatory and met with outrage by a variety of organizations from almost all parties thus involved. Several countries banned the film for specific or general insults to the dignities of countries and cultures mentioned, alluded to, or used in the film. |

||

* The [[The Adventures of Tintin|Tintin book]] ''[[The Castafiore Emerald]]'' heavily criticises antiziganism, as the Romanis who move onto [[Captain Haddock]]'s property are falsely accused of stealing [[Bianca Castafiore]]'s priceless [[emerald]], though they are innocent. |

* The [[The Adventures of Tintin|Tintin book]] ''[[The Castafiore Emerald]]'' heavily criticises antiziganism, as the Romanis who move onto [[Captain Haddock]]'s property are falsely accused of stealing [[Bianca Castafiore]]'s priceless [[emerald]], though they are innocent. |

||

Revision as of 19:10, 20 August 2012

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

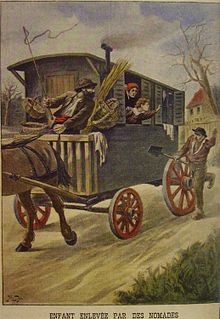

Antiziganism or Anti-Romanyism or Anti-Gypsyism is hostility, prejudice or racism directed at the Romani people, also known as Gypsies.

As an endogamous culture with a tendency to practise self-segregation[citation needed], the Romanis have generally resisted assimilation with the indigenous communities of whichever countries they have moved to; they have thus successfully preserved their distinctive and unique culture.

The price of this cultural longevity, however, has been a degree of isolation from the surrounding population that has made them vulnerable to being stereotyped as thieves, tramps, con men and fortune tellers. Due in part to this same cultural segregation, the Romanis have been subject to various forms of discrimination throughout history and in nearly all the countries in which they have settled.

Etymology

The root zigan (pronounced [ˈtsiɡaːn]) is the basis of the word given to the Roma people in many European languages. Note however, that in several regions[which?] "zigan" and its variations are considered derogatory and offensive.[citation needed] Many activists[who?] and scholars[who?] prefer the phrase "Roma-phobia".[citation needed]

History of antiziganism

In the Middle Ages

In the early 13th century Byzantine records, the Atsínganoi are mentioned as "wizards... who are inspired satanically and pretend to predict the unknown."[1] By the 16th century, many Romanies in Eastern and Central Europe worked as musicians, metal craftsmen, and soldiers.[2] As the Ottoman Turks expanded into the territory of modern Bulgaria, they relegated Romanies, seen as having "no visible permanent professional affiliation", to the lowest rung of the social ladder.[3]

In Royal Hungary (present-day West-Slovakia, West-Hungary and West-Croatia), strong anti-Romani policies emerged since they were increasingly seen as Turkish spies or as a fifth column. In this atmosphere, they were expelled from many locations and increasingly adopted a nomadic way of life.[4]

The first anti-Romani legislation was issued in March of Moravia in 1538, and three years later, Ferdinand I ordered that Romanies in his realm be expelled after a series of fires in Prague. Seven years later, the Diet of Augsburg declared that "whosoever kills a Gypsy, will be guilty of no murder."[5] In 1556, the government stepped in to "forbid the drowning of Romani women and children."[6]

In England, the Egyptians Act 1530 banned Romanies from entering the country and required those living in the country to leave within 16 days. Failure to do so could result in confiscation of property, imprisonment and deportation. The act was amended with the Egyptians Act 1554, which directed that they abandon their "naughty, idle and ungodly life and company" and adopt a settled lifestyle. However, for those who failed to adhere to a sedentary existence the Privy council interpreted the act to permit execution of non-complying Romanies 'as a warning to others'.[7]

18th century

In 1710, Joseph I issued an edict against the Romani, ordering "that all adult males were to be hanged without trial, whereas women and young males were to be flogged and banished forever." In addition, they were to have their right ears cut off in the kingdom of Bohemia, in the March of Moravia, the left ear. In other parts of Austria they would be branded on the back with a branding iron, representing the gallows. These mutilations enabled authorities to identify them as Romani on their second arrest. The edict encouraged local officials to hunt down Romani in their areas by levying a fine of 100 Reichsthaler for those failing to do so. Anyone who helped Romani was to be punished by doing a half-year's forced labor. The result was "mass killings" of Romani. In 1721, Charles VI amended the decree to include the execution of adult female Romani, while children were "to be put in hospitals for education."[8]

In 1774, Maria Theresa of Austria issued an edict forbidding marriages between Romani. When a Romani woman married a non-Romani, she had to produce proof of "industrious household service and familiarity with Catholic tenets", a male Rom "had to prove ability to support a wife and children", and "Gypsy children over the age of five were to be taken away and brought up in non-Gypsy families."[9]

A panel was established in 2007 by the Romanian government to study the 18th and 19th century use of Romani as slaves for Princes, local landowners, and monasteries. Slavery of Romani was outlawed in Romania around 1856.[10]

19th century

Petty theft was a regular justification for persecution of Romanies. In 1899, the Nachrichtendienst in Bezug auf die Zigeuner ("Intelligence Service Regarding the Gypsies") was set up in Munich under the direction of Alfred Dillmann, cataloguing data on all Romani individuals throughout the German lands. It did not officially close down until 1970. The results were published in 1905 in Dillmann’s Zigeuner-Buch,[11] that was used in the following years as justification for the Porajmos. It described the Romani people as a "plague" and a "menace", but almost exclusively presented as Gypsy crime trespassing and the theft of food.[11]

Porajmos

Persecution of Romani people reached a peak during World War II in the Porajmos, the Nazi genocide of Romanis during the Holocaust. Because the Romani communities of Eastern Europe were less organized than the Jewish communities, it is more difficult to assess the actual number of victims though the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Research Institute in Washington puts the number of Romani lives lost by 1945 at between 500,000 and 1.5 million. Former ethnic studies professor Ward Churchill has argued that the Romani population suffered proportionally more genocide than the Jewish population of Europe and that their plight has largely been sidelined by scholars and the media.[12]

The extermination of Romanies by the German Nazi authorities in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was so thorough that the Bohemian Romani language became an extinct language. The policy of the Nazis varied across countries they conquered: they killed almost all the Romanis in the Baltic countries, yet they did not attempt to eliminate the Romanis in Denmark or Greece.

Romanies were also persecuted by the fascist Ustaše in Croatia, who were allied to the Nazis. As a result, there were hardly any Romanies left in Croatia after the war.

Contemporary antiziganism

According to a report issued by Amnesty International in 2011, "...systematic discrimination is taking place against up to 10 million Roma across Europe. The organization has documented the failures of governments across the continent to live up to their obligations".[14]

Antiziganism has continued in the 2000s, particularly in Germany, France, England, Romania, Bulgaria, Slovakia,[15] Hungary,[16] Slovenia[17] and Kosovo.[18]

Romanis often live [citation needed] in low-class ghettos, are subject to discrimination in jobs and schools, and are often subject to police brutality. In Bulgaria, professor Ognian Saparev has written articles stating that 'Gypsies' should be confined to ghettos because they do not assimilate, are culturally inclined towards theft, have no desire to work, and use their minority status to 'blackmail' the majority.[citation needed] European Union officials censured both the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2007 for forcibly segregating Romani children from normal schools.[19]

The manele, their modern music style, was prohibited in some cities of Romania in public transport[20] and taxis[21][22], that actions being justified by buses and taxis companies as being for passenger's comfort and a pleasant ambience. However that actions had been characterised by Speranta Radulescu, a professor of ethno-musicology at the Bucharest Conservatory, as "a defect of Romanian society".[23].There were also a few criticisms of the Professor's Dr. Ioan Bradu Iamandescu experimental study, which linked the listening of "manele" to increased level of aggressiveness and low autocontrol and set a correlation between preference for that music style and low cognitive skills.[24][25]

As of 2006, many Romanies who had previously lived in Kosovo, lived in displaced refugee communities in Montenegro and Serbia. Those who remain often fear attacks from ethnic Albanians who see them as "Serb Collaborators". In February 2007, three Romani women in Slovakia received compensation after suing a hospital for sterilizing them while they were underage and without their consent. While the sterilizations occurred in 1999 and 2002, and the women had been repeatedly appealing to prosecutors since then, they were up until this time ignored.[citation needed]

The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights Thomas Hammarberg has been an outspoken critic of Antiziganism, both in reports and periodic Viewpoints. In August 2008, Hammarberg noting that "today's rhetoric against the Roma is very similar to the one used by Nazis and fascists before the mass killings started in the thirties and forties. Once more, it is argued that the Roma are a threat to safety and public health. No distinction is made between a few criminals and the overwhelming majority of the Roma population. This is shameful and dangerous."[26]

According to the latest Human Rights First Hate Crime Survey, Romanies routinely suffer assaults in city streets and other public places as they travel to and from homes, workplaces, and markets. In a number of serious cases of violence against Romani people, attackers have also sought out whole families in their homes, or whole communities in settlements predominantly housing Romanis. These widespread patterns of violence are sometimes directed both at causing immediate harm to Romanis, without distinction between adults, the elderly, and small children and physically eradicating the presence of Romani people in towns and cities in several European countries.[27]

Europe (European Union)

The practice of placing Romani students in segregated schools or classes remains widespread in countries across Central and Eastern Europe.[28] In Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, and Slovakia, many Romani children have been channeled into all-Romani schools that offer inferior quality education and are sometimes in poor physical condition, or into segregated all-Romani or predominantly Romani classes within mixed schools.[29] In Hungary, Bulgaria, and Slovakia, many Romani children are sent to classes for pupils with learning disabilities, regardless of whether such classes are appropriate for the children in question or not. In Bulgaria, they are also sent to so-called "delinquent schools", where a variety of human rights abuses take place.[29]

Romani in European population centers are often accused of crimes such as pickpocketing. In 2009 a documentary by BBC called Gypsy child thieves uncovered how Gypsy children are kidnapped and abused by Gypsy gangs from Romania. The children are often held locked in sheds during the nights and sent to steal during the days. In Milan, Italy, it is estimated that a single Gypsy child is able to steal as much as €12,000 in a month; there were as many as 50 of such abused Gypsy children operating in the city. Meanwhile, the Romani bosses of these gangs build glossy villas back in Romania. The film went on to describe the link between poverty, discrimination, crime and exploitation.[30]

A UN study[31] found that Romanis in Eastern European countries such as Bulgaria are arrested for robbery at a much higher rate than other groups. Amnesty International[32] and Romanis groups such as the Union Romani blame widespread police and government racism and persecution.[33] In July 2008, a Business Week feature found the region's Romani population to be a "missed economic opportunity."[34] Hundreds of people from Ostravice in the Beskydy mountains signed a petition against a plan to move Romani families from Ostrava city to their home town, fearing the Romani invasion as well as their schools not being able to cope with the influx of Romani children.[35]

In 2009, the UN's anti-racism panel charged that "Gypsies suffer widespread racism in European Union." that 'Racially motivated crime is an everyday experience' for Roma people, says EU's Fundamental Rights Agency.'.[36]

Bulgaria

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2011) |

Despite the low birth rate in the country, Bulgaria's Health Ministry was considering a law aimed at lowering the birth rate of certain minority groups, particularly the Romanis, owing to the high mortality rate among Romani families, which are typically large. This was later abandoned because of conflict with EU law and the Bulgarian constitution.[37]

Attaka have also been accused of fueling of antiziganist feeling.

In 2011 in Bulgaria, widespread Anti-Roma protests occurred in response to the murder of Angel Petrov on the orders of Kiril Rashkov, a Roma leader in the village of Katunitsa. In the subsequent trial, the killer - Simeon Yosifov was sentenced to 17 years in jail.[38] As of May 2012, an appeal is under way.

Czech Republic

Roma make up 2-3% of population in the Czech Republic. According to Říčan (1998), Roma make up more than 60% of Czech prisoners and about 20-30% earn their livelihood in illegal ways, such as prostitution, trafficking and other property crimes.[39] Roma are thus more than 20 times overrepresented in Czech prisons than their population share would suggest.

The high crime rate and asocial behavior creates fear and hostility. According to 2010 survey, 83% of Czechs consider Roma asocial and 45% of Czechs would like to expel them out of Czech Republic.[40] A 2011 poll, which followed after a number of brutal attacks by Romani perpetrators against majority population victims, revealed that 44% of Czechs are afraid of Roma people.[41] The majority of the Czech people do not want to have Romanies as neighbours (almost 90%, more than any other group[42]) seeing them as thieves and social parasites. In spite of long waiting time for a child adoption, Romani children from orphanages are almost never adopted by Czech couples.[43] After the Velvet Revolution in 1989 the jobs traditionally employing Romanis either disappeared or were taken over by workers from Ukraine, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, Mongolia and even Nigeria.

While the general attitude of Czech population towards Roma minority is negative, occurrences of anti-Roma violence are condemned by the public and repressed by the authorities.[citation needed] Among highly medialized cases was Vítkov arson attack of 2009, in which four right-wing extremists seriously injured 3 year old Romani girl. The public responded by donating money as well as presents to the family, which was in the end able to buy a new house from the donations, while the perpetrators were sentenced to 18 and 22 years in prison.

The Gypsies and Romanis are in the centre of agenda of far-right groups in the Czech Republic, which are spreading antiziganism especially in connection with criminal acts rendered by Romani perpetrators on majority population victims, focusing especially on cases of rapes and murders, such as nearly killing and rape of a 13-year-old boy in Duchcov or rape of a 17-year-old girl in church in Nový Bydžov,[44] or brutal murder of an 81-year-old woman in Olešnice by gang of Romani children, who were sent to commit the crime by father of one of them in order to exploit lower ranges of punishment available for minors.[45] Far-right groups often hold demonstrations in places, where majority population suffers from high crime rates attributed to Romani perpetrators.[46][47][48] Far-right groups also organize "crime patrols" in such places.[49][50] (these are however no militia style patrols, they rather rely on requesting police presence). Far-right is also promoting repatriation of Roma to India on voluntary basis, arguing that the Czech state should offer paying all the costs, including establishment of their new livelihood there.[51][52] There are some Romani groups calling for a similar plan, however instead of India they are requesting relocation to Germany, France, United Kingdom, Denmark, Sweden, Finland or Belgium, while in their view the Czech Republic should reimburse costs.[53]

In January 2010, Amnesty International launched a report titled Injustice Renamed: Discrimination in Education of Roma persists in the Czech Republic.[54] According to the BBC, it was Amnesty's view that while cosmetic changes had been introduced by the authorities, little genuine improvement in addressing discrimination against Romani children has occurred over recent years.[55]

Denmark

In Denmark, there was much controversy when the city of Helsingør decided to put all Romani students in special classes in its public schools. The classes were later abandoned after it was determined that they were discriminatory and the Romanis were put back in regular classes.[56]

France

France has come under criticism for its treatment of Roma. In the summer of 2010 French authorities demolished at least 51 illegal Roma camps and began the process of repatriating their residents to their countries of origin.[57] The French government has been accused of perpetrating these actions to pursue its political agenda.[58]

Germany

After 2005 Germany deported some 50,000 people, mainly gypsies and Romanis, to Kosovo. These were asylum seekers who fled the country during the Kosovo War. The people were deported after living more than 10 years in Germany. The deportations were highly controversial: many were children, who obtained education in Germany, spoke German as their primary language and considered themselves as Germans.[59]

Hungary

Hungary has seen escalating violence against the Romani people. On 23 February 2009, a Romani man and his five-year-old son were shot dead in Tatárszentgyörgy village southeast of Budapest as they were fleeing their burning house which was set alight by a petrol bomb. The dead man's two other children suffered serious burns. Suspects were arrested and are currently on trial.[60]

Another commentator feels that Hungary is on the brink of a race war with the ethnic Hungarian paramilitary Magyar Garda in confrontation with the Romani Garda.[61]

In 2008 Marioara Rostas, a teenage Roma girl was abducted in Dublin city centre, reportedly by member(s) of a local notorious crime family. Over the next week she was raped vaginally, anally and oraly multiple times, abused, brutalized, including having her teeth removed, and shot dead.[62][63] Her body was discovered in the Wicklow Mountains four years later in a crime that shocked the Irish Garda Representative Association (GRA) on indifference to the crime within Irish society and why had there been no "outpourings of disgust that such depravity could be committed here".[64]

The lack of public outcry in Ireland led journalist Cormac O’Keeffe of the Irish Examiner to write: "Kidnapped, gang raped, tortured, shot and dumped, but no one cares" in March 2012.[62] There were expressions of anti-Roma sentiment made in the comments section of the newspaper's web site[65] and several follow-up article commenting on the country's attitude to Romanian Roma immigration.[65][66] Subsequent articles entitled “We must fight Irish prejudice” highlighting an undercurrent of racism in Ireland.[66] The Integration Centre in Dublin stated that Roma people were: "routinely demonized and dehumanised."[64] It is likely that this dehumanization was a factor in the rape, torture and murder of the girl. Is it also likely that this dehumanization was a factor in the indifference that greeted the news and detail of her death."[64] The Irish Travellers' Movement said they would send out a "strong message that no one deserves to die so young and in such a horrific violent way". Members of Pavee Point, an indigenous Irish Traveller organization, Roma and members of the settled community led a small candle-lit vigil with the media and Garda members in attendance in February 2012, close to the last reported sighting of the Roma teenager.[67]

No one as yet has been charged with her murder.

Italy

The country is home to about 150,000, who live mainly in squalid camps on the outskirts of major cities such as Rome, Milan and Naples. They amount to less than 0.3 per cent of the population, one of the lowest proportions in Europe. In general, the ethnic group lives apart and is often blamed for petty theft and burglaries.[citation needed]

In 2007 and 2008, following the brutal murder of a woman in Rome at the hands of a young man from a local Romani encampment,[68] the Italian government started a crackdown on illegal Roma and Sinti campsites in the country.

In May 2008 Romani camps in Naples were attacked and set on fire by local residents.[69] In July 2008, a high court in Italy overthrew the conviction of defendants who had publicly demanded the expulsion of Romanis from Verona in 2001 and reportedly ruled that "it is acceptable to discriminate against Roma on the grounds that they are thieves."[70] One of those freed was Flavio Tosi, Verona's mayor and an official of the anti-immigrant Lega Nord.[70] The decision came during a "nationwide clampdown" on Romanis by Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi. The previous week, Berlusconi's interior minister Roberto Maroni declared that all Romanis in Italy, including children, would be fingerprinted.[70]

Opposition party member, Gianclaudio Bressa, responded by insisting that these measures "increasingly resemble those of an authoritarian regime".[70] In response to the fingerprinting plan, three United Nations experts testified that "by exclusively targeting the Roma minority, this proposal can be unambiguously classified as discriminatory."[71] The European Parliament denounced the plan as "a clear act of racial discrimination" and asked the Italian government not to continue.[71]

A short time later, in July 2008, the deaths of Cristina and Violetta Djeordsevic, two Roma children who drowned while Italian beach-goers in Naples remained unperturbed, brought additional international attention to the strained relationship between Italians and the Roma people.

Slovakia

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2011) |

United Kingdom

In the UK, racism and animosity against Roma, Romanichal, British Romanies and other Travelling groups is still endemic within Britain and until the 1960s it was common to hang signs in pubs declaring “No Blacks, No dogs, No Gypsies”.[72] In 2008 the media reported that Gypsies experience a higher degree of racism than any other group in the UK, including asylum-seekers, and a Mori poll indicated that a third of UK residents admitted openly to being prejudiced against Gypsies.[72] The term "travellers" (referring to Scottish Travellers, New Age Travellers as well as Romanichal, Roma, Funfair Travellers, and Irish Travellers) became a 2005 general election issue, with the leader of the Conservative Party Michael Howard, promising to review the Human Rights Act 1998. This law, which absorbs the European Convention on Human Rights into UK primary legislation, is seen by some to permit the granting of retrospective planning permission. Severe population pressures and the paucity of greenfield sites have led to travellers purchasing land and setting up residential settlements very quickly, thus subverting the planning restrictions.[citation needed]

Travellers argued in response that thousands of retrospective planning permissions are granted in Britain in cases involving non-Romani applicants each year and that statistics showed that 90% of planning applications by Romanis and travellers were initially refused by local councils, compared with a national average of 20% for other applicants, disproving claims of preferential treatment favouring Romanis.[73] They also argued that the root of the problem was that many traditional stopping-places had been barricaded off and that legislation passed by the previous Conservative government had effectively criminalised their community, for example by removing local authorities’ responsibility to provide sites, thus leaving the travellers with no option but to purchase unregistered new sites themselves.[74]

England

In 2002 Conservative Party politician, and Member of Parliament (MP) for Bracknell Andrew MacKay stated in a House of Commons debate on unauthorised encampments of Gypsies and other Travelling groups in the UK that “They [Gypsies and Travellers] are scum, and I use the word advisedly. People who do what these people have done do not deserve the same human rights as my decent constituents going about their ordinary lives”.[75][76] MacKay has since left politics in 2010.[77]

In 2005 Doncaster Borough Council discussed in chamber a Review of Gypsy and Traveller Needs[78] and concluded that Gypsies and Irish Travellers are among the most vulnerable and marginalised ethnic minority groups in Britain. ‘No Travellers’ signs in pubs and shops can still be seen today, and councils no longer have a statutory duty to provide sites for Gypsy and Traveller families, spending small fortunes each year evicting them, instead. Gypsy and Traveller children are taunted and bullied in school, local residents are openly hostile to them, and scare stories in the media fuel prejudice and make racist attitudes acceptable.[79][80]

In 2008 Travellers and Gypsies were refused entry to the Royal Windsor Horse Show, Windsor Home Park, for no other reason than because they were Gypsies or Travellers. One steward is reported as saying "The Queen does not want your kind here!". When later questioned on the denial of entry, an offence under the Race Relations Act 1976, the show's organisers agreed that the stewards were under instructions not to allow entry to Gypsies or Travellers to the event.[81]

A Gypsy and Traveller support centre in Leeds, West Yorkshire, was vandalised in April 2011 in what the police suspect was a hate-crime. The fire caused substantial damage to the centre which is used as a base for the support and education for Gypsies and Travellers in the community.[82]

In January 2012 a duty manager at an Ice Arena in Blackburn, Lancashire, placed a ‘No Travellers’ sign (a term including Gypsies and Travellers) at the main reception for five days before it was taken down. The management issued an apology after they were contacted by the Lancashire Telegraph. The Gypsy Council said the sign was "inflammatory, illegal and in danger of inciting racial hatred". The Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Achievement Service for Lancashire County Council said that if the sign had not been removed, legal action could have been taken.[83]

Scotland

The Equal Opportunities Committee of the Scottish Parliament in 2001[84] and in 2009[85] confirmed that widespread marginalization and discrimination persists in Scottish society against Gypsy/Traveller groups. The 2009 survey also concludes that Scottish Gypsy/Travellers had been largely ignored in official policies. A similar survey in 2006 found discriminatory attitudes in Scotland towards Gypsies/Travellers,[86] and showed 37% of those questioned would be unhappy for a relative married a Gypsy/Traveller. While 48% found it unacceptable if a member of the Gypsy/Traveller minorities became Primary School teachers.[87]

A report by the University of the West of Scotland found that both the Scottish and UK governments, have failed to play their part in safeguarding the rights of the Roma as a recognized ethnic group and raise awareness of Roma rights within the UK.[88]

Amnesty International report in 2012 that Gypsy/Traveller groups in Scotland routinely suffer widespread discrimination in society,[89] and by the media where Scottish Gypsy/Traveller groups receives a disproportionate level of scrutiny.[90] Over a four month period as a sample 48% of articles showed Gypsies/Travellers in a negative light, while 25-28% of articles were favourable or of a neutral viewpoint.[91] Amnesty recommended journalists adhere to ethical codes of conduct when reporting on Gypsy/Traveller populations in Scotland and these groups face fundamental human rights concerns – particularly with regards to health, education, housing, family life and culture.[92]

To tackle the widespread prejudices and needs of Gypsy/Traveller minorities, in 2011 the Scottish Government set up a working party to consider how best to improve community relations between Gypsies/Travellers and Scottish society.[93] Including young Gypsies/Travellers to engage in an on-line positive messages campaign, contain factually correct information on their communities.[94]

Wales

In 2007 a study by the newly formed Equality for Human Rights Commission found that negative attitudes and prejudice persists against Gypsy/Traveller communities in Wales.[95] Results showed that 38% of those questioned would not accept a long-term relationship with, or would be unhappy if a close relative married or formed a relationship with a Gypsy or Traveller. Furthermore, only 37% found it acceptable if a member of the Gypsy/Traveller minorities became Primary School teachers, the lowest score of any group.[96] An advertising campaign to tackle prejudice in Wales was launched by the Equality for Human Rights Commission in 2008.[97]

Northern Ireland

In June 2009, having had their windows broken and deaths threats made against them, twenty Romanian Romani families were forced from their homes in Lisburn Road, Belfast, in Northern Ireland. Up to 115 people, including women and children, were forced to seek refuge in a local church hall after being attacked. They were later moved by the authorities to a safer location.[98] An anti-racist rally in the city on 15 June to support Romani rights was attacked by youths chanting neo-Nazi slogans. The attacks were condemned by Amnesty International[99] and political leaders from both the Unionist and Nationalist traditions in Northern Ireland.[100][101]

Following the arrest of three local youths in relation to the attacks, the church where the Romanies had been given shelter was badly vandalised. Using 'emergency funds', Northern Ireland authorities assisted most of the victims to return to Romania.[102][103]

Europe (non EU)

Norway

In Norway, many Romani people were forcibly sterilized by the state until 1977.[104][105]

Antiziganism in Norway flared up in July 2012 when roughly 200 Romani people settled outside Sofienberg church in Oslo and were later relocated to a building site at Årvoll, in northern Oslo. The group was subjected to hate crimes in the form of stone throwing and fireworks being aimed at, and fired into their camp. They, and Norwegians trying to assist them in their situation, also received death threats.[106] The leader of the right wing Progress Party also advocated the expulsion of the Romani people resident in Oslo,[107] in direct contravention of the Schengen Agreement.

Kosovo

In the aftermath of the Kosovo War, the Society for Threatened Peoples estimated that 80% of Kosovo's 150,000 Romanis were expelled by the Albanian population.[108] At UN internally displaced persons' camps in Kosovo for Romanis, the refugees were exposed to lead poisoning.[109]

Switzerland

A Swiss right-wing magazine Weltwoche, published a photograph of a gun-wielding Roma child on its cover in 2012 with the title “The Roma are coming: Plundering in Switzerland”. They claimed in a series of articles of a growing trend in the country of “criminal tourism for which eastern European Roma clans are responsible” with professional gangs specializing in burglary, thefts, organized begging and street prostitution.[110] The magazine immediately came under criticism with its links to the right-wing populist People’s Party (SVP), as being deliberately provocative and encouraged racist stereotyping by linking ethnic origin and criminality.[110] Switzerland’s Federal Commission against Racism is considering legal action after complaints in Switzerland, Austria and Germany that the cover breached anti-racism laws.

The Berlin newspaper Tagesspiegel investigated the origins of the photograph taken in the slums of Gjakova, Kosovo, where Roma communities were displaced during the Kosovo War to hovels built on a toxic landfill.[111] The Italian photographer Livio Mancini, denounced the abuse of his photograph which was originally taken to demonstrate the plight of Roma families in Europe.[112]

United States

Laws of some states forbade the Roma people from living as one with their fellow Americans.[113] In New Jersey, a law (so called Gipsy Law)[114] had been enacted in 1917 and repealed in 1998, that allowed local governments to craft laws and ordinances that specified where Gypsies could entertain and rent property, and what goods they could sell.[113]

Law enforcement agencies in the United States hold regular conferences[115] on the Romani people and similar nomadic groups. It is common to refer to the operators of certain types of travelling con artists[116] and fortune-telling[117] businesses as "gypsies," as the term in the United States has come to designate any peoples with a nomadic lifestyle rather than a specific ethnic group. Additionally, a common derogatory phrase in the US is to "be gypped," as in "I was gypped" or "he gypped me," meaning that someone executed a bad deal or took money that he was not entitled to take.

Canada

When Romani refugees were allowed into Canada in 1997, a protest was staged by 25 people, including neo-Nazis, in front of the motel where the refugees were staying. The protesters held signs that said, for examples, "Honk if you hate Gypsies," "Canada is not a Trash Can," and "G.S.T. — Gypsies Suck Tax." (The last is a reference to Canada's Goods and Services Tax, also known as GST.) The protesters were charged with promoting hatred, and the case, called R. v. Krymowski, reached the Supreme Court of Canada in 2005.

Environmental struggles

This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2010) |

Environmental issues arising from Cold War-era industrial development, particularly in Eastern Europe, disproportionately impacts the Roma, a condition many analysts consider a form of environmental racism . Their traditionally nomadic lifestyle most often pushes them to the outskirts of towns and cities, where amenities are less available and employment and educational opportunities are even rarer.

While the economic restructuring of a command economy into a western style market economy created hardships for most Hungarians, with the national unemployment rate heading toward 14 percent and per capita real income falling, the burdens imposed on Romas are disproportionately great.[118]

The various legal blocks to their traditional nomadic lifestyle have forced many travelling Roma into unsafe areas such as former industrial areas or former landfill or other waste areas where pollutants may have impacted runoff into rivers or streams or even groundwater. The lack of provisioned stopping places deny Roma access to clean water or sanitation facilities, rendering Roma more vulnerable to disease and/or complications of illnesses:

Denied environmental benefits such as water, sewage treatment facilities, sanitation and access to natural resources, and suffer from exposure to environmental hazards due to their proximity to hazardous waste sites, incinerators, factories, and other sources of pollution[126]

Environmental racism has also driven governments in their attempts to "settle" the Roma within habitable areas, both in the legal and/or social obligation itself to have a fixed address and in the motivation of integrating Roma into the broader population. Where Roma are settled in many areas of central and eastern Europe, the distance of such housing from the commercial centers of cities and the lack of amenities nearby pose significant barriers to working or education, particularly when public transit is lacking. Here, again, even running water may be an issue, complicated further by the Roma's cultural practices of hygiene. “While most of Sofia, the capital city of Bulgaria, is connected to the public water and sewerage system, there is only one tap for every 200 families in Glavova “mahala”, an area in Sofia where Roma live.”

Water-borne diseases, such as diarrhoea and dysentery, are an almost constant feature of daily life, especially for children. Médecins Sans Frontières, which runs the only medical centre in Fakulteta, estimates infant mortality among Roma children to be six times higher than in the rest of the Bulgarian population.[126]

Additionally, the permanent settlement of Roma is often met with either hostility by non-Roma or by the exodus of non-Roma from neighbourhoods to which Roma have been relocated, similarly to the "[white flight]" phenomenon in the United States. Krista Harper argues:

that in the case of Roma in CEE, spaces inhabited by low-income Roma have come to be “racialized” during the post-socialist era, intensifying patterns of environmental exclusion along ethnic lines.[127]

Other areas earmarked for Roma settlement are often situated amongst hazardous facilities. Again Harper asks:

Is it an accident that Roma shantytowns are frequently located next to landfills, on contaminated land, or that they are regularly exposed to floods? Why do water pipelines end on the edges of their settlements, so that people have to walk miles every day just to collect potable water for cooking and drinking?[127]

Moreover,

Local councils have issued ordinances banning Roma from settlements.10 Roma are frequently evicted, and many observers have noted a trend to remove Roma from town centers and relocate them to inferior ghettoized housing on the periphery.[128]

In a specific case, men living in the Roma village of Heves found car batteries and began to disassemble them, exposing themselves and many others to lead that came from within. However, legal recourse for this and similar cases is exceeding difficult due to the lack of rights for Roma acknowledged by governments.

The four patterns of the unequal distribution of environmental benefits and harm identified in the research are: 1) exposure to hazardous waste and chemicals (settlements at contaminated sites); 2) vulnerability to floods; 3) differentiated access to potable water; and 4) discriminatory waste management practices. While the four identified patterns of environmental injustice may not (and probably they do not) represent all potential forms of environmental injustice, they summarize patterns identified in the field research.[127]

According to a study by the [United Nations Development Program], the percentage of Roma with access to running water and sewage treatment within Romania and the Czech Republic is well below the average in those countries, with a proliferation of skin diseases among these populations due to the lack of housing standards, including scabies, pediculosis, pyodermatitis, mycosis and askaridosis. There is also a recognition of respiratory health problems that occurs in the majority of the inhabitants of the areas. Other diseases that are increasing in majority Roma populations are [hepatitis] and [tuberculosis.] Aside from the UNDP, very few organizations devote significant time or resources to addressing environmental concerns that specifically impact on the Roma.

There are one or two people-not one or two groups, but one or two people- who are working on Gypsy issues…other than that, I have not heard of any Roma environmentalism. When I asked environmentalists why their groups did not deal with the problems of Roma Communities, the most frequent response was that the main problems of the Roma were poverty and access to education and that these were “social” issues, not environmental issues.[129]

Antiziganism in popular culture

- The European Center for Antiziganism Research officially filed a complaint against Sacha Baron Cohen — who plays Borat in the eponymous mockumentary film Borat — for inciting violence and violating Germany's anti-discrimination laws.[130] One part of the satirical film, which purportedly portrays Borat's impoverished native village in Kazakhstan, actually shows a Romani village in Romania. Note that neither Mr. Cohen himself, his character, nor the plot bear any relation whatsoever to either Kazakhstan or Romania (or their people - be they Romani, Kazakh, Romanian, Russian, etc.), and the attribution of this generic "barbaric foreigner from an unpleasant backwards country" to specific cultures or locales was widely seen as inflammatory and met with outrage by a variety of organizations from almost all parties thus involved. Several countries banned the film for specific or general insults to the dignities of countries and cultures mentioned, alluded to, or used in the film.

- The Tintin book The Castafiore Emerald heavily criticises antiziganism, as the Romanis who move onto Captain Haddock's property are falsely accused of stealing Bianca Castafiore's priceless emerald, though they are innocent.

- Claude Frollo, the antagonist of Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre Dame, was portrayed as having a strong, genocidal hatred of gypsies in Disney's animated adaptation of the story.

References

- ^ George Soulis (1961): The Gypsies in the Byzantine Empire and the Balkans in the Late Middle Ages (Dumbarton Oak Papers) Vol.15 pp.146-147, cited in David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) ISBN 0-312-08691-1 p.1

- ^ David Crowe (2004): A History of the Gypsies of Eastern Europe and Russia (Palgrave Macmillan) ISBN 0-312-08691-1 p.XI

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.2

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.1, p.34

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.34

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.35

- ^ Mayall, David (1995). English gypsies and state policies. f Interface collection Volume 7 of New Saga Library. Vol. 7. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. pp. 21, 24. ISBN 978-0-900458-64-4. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.36-37

- ^ Crowe (2004) p.75

- ^ "Company News Story". Nasdaq.com. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b Dillmann, Alfred (1905). Zigeuner-Buch (in German). Munich: Wildsche.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Patrin © 1997. "Truth & Memory". Archived from the original on 25 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Basescu chided for 'gypsy' remark". BBC News. 23 May 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- ^ "Amnesty International – International Roma Day 2011 Stories, Background Information and video material" (PDF). AI Index: EUR 01/005/2011: Amnesty International. 7 April 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Amnesty International". Web.amnesty.org. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Hungary's anti-Roma militia grows | csmonitor.com

- ^ "roma | Human Rights Press Point". Humanrightspoint.si. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker - Society for Threatened Peoples. "Roma and Ashkali in Kosovo: Persecuted, driven out, poisoned". Gfbv.de. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "IHT.com". IHT.com. 29 March 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Corina Misăilă, Vali Trufaşu (28). "Primăria de decis: Manelele lui Guţă şi Salam sunt interzise la Galaţi". Stiri din Galati. Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Interzis la manele în taxi!". Liber Tatea (in Romanian). Ringier Romania Toate. 31. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Sebastian Dan (14). "Fumatul şi manelele, interzise în taxiurile braşovene". Adevărul.ro (in Romanian). Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ ""Manele", the Most Contested Music of Today". Radio Romania International. 06-02-2012. Retrieved 23-06-2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Mariana Minea (10). "Prof. dr. Ioan Bradu Iamandescu: „Pe muzică barocă, neuronii capătă un ritm specific geniilor"". Adevărul.ro (in Romanian). Adevărul Holding. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Cum se comporta creierul cand asculta manele". Stirileprotv.ro (in Romanian). Stirileprotv.ro. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Viewpoints by Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights". Coe.int. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Human Rights First Report on Roma". Humanrightsfirst.org. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "The Impact of Legislation and Policies on School Segregation of Romani Children". European Roma Rights Centre. 2007. pp. p8. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Equal access to quality education for Roma, Volume 1" (PDF). Open Society Institute - EU Monitoring and Advocacy Program (EUMAP). 2007. pp. 18–20, 187, 212–213, 358–361. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2007.

- ^ Bagnall, Sam (2 September 2009). "How Gypsy gangs use child thieves". BBC News.

- ^ Ivanov, Andrey (2002). "7". Avoiding the Dependence Trap: A Regional Human Development Report. United Nations Development Programme. ISBN 92-1-126153-8.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Denesha, Julie (2002). "Anti-Roma racism in Europe". Amnesty International. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Rromani People: Present Situation in Europe". Union Romani. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ by S. Adam Cardais (28 July 2008). "Businessweek.com". Businessweek.com. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Centrum.cz Template:Cs icon

- ^ Traynor, Ian (23 April 2009). "Gypsies suffer widespread racism in European Union". London: Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 August 2010. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ivanov, Ivan (11 October 2006). "Women's reproductive rights and right to family life interferance by the Health Minister". Social Rights Bulgaria.

- ^ "Anti-Roma Protests Escalate - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. 29 September 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Říčan, Pavel (1998). S Romy žít budeme - jde o to jak : dějiny, současná situace, kořeny problémů, naděje společné budoucnosti. Praha: Portál. pp. 58–63. ISBN 80-7178-250-5.

- ^ Jiří Šťastný (8 February 2012). "Češi propadají anticikánismu, každý druhý tu Romy nechce, zjistil průzkum". Zpravy.idnes.cz. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "http://www.tyden.cz/rubriky/domaci/romsky-bloger-nekteri-romove-se-chovaji-jako-blazni_216270.html" (in Czech). Retrieved 1 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Czech don't want Roma as neighbours" (in Czech). Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ "What is keeping children in orphanages when so many people want to adopt? - 07-02-2007 - Radio Prague". Radio.cz. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Duchcov rape and attempted murder of a 13-year-old, in which two young Romani boys first explained to the Czech boy, that they will show him "the treatment the gypsies underwent in the concentration camps". Afterwards they beat him, raped him, took his property (i.e. mobile phone) and when he fell unconscious they left him severely wounded on a railway track. While one of the Romani perpetrators couldn't be prosecuted due to his age, the other one was found guilty of sexual abuse, blackmailing, rape, robbery and racially motivated attempted murder. The 16-year-old Romani perpetrator was punished with sentence of 10 years in prison, the maximum a minor may obtain in the Czech Republic, see "Šestnáctiletý Rom dostal za zbití jiného chlapce deset let". Tyden.cz. 2010. Retrieved 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) The appeal court had however not found the defendant guilty of attempted murder, and sentenced him only to five years in prison, see "Trest pro romského mladíka, který týral chlapce, se smrskl na půlku". iDNES.cz. 17 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2011. For wide criminal activity and a rape by Romani perpetrators in Nový Bydžov, see ČTK (10 March 2011), Na demonstrace proti Romům v Novém Bydžově míří až 1000 lidí, retrieved 15 March 2011 - ^ Gang dětských vrahů před soud, 14 March 2005, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "VIDEO: Bitva v Janově - těžká zranění na obou stranách", Ústecký deník, 11 November 2008, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "Neonacisté se v Přerově střetli s policií", ČT 24, 4 April 2009, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "Nový Bydžov mobilizuje kvůli demonstraci extremistů", aktuálně.cz, 10 March 2011, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "Pochod hlídek Dělnické strany v Janově se obešel bez incidentů", iDNES.cz, 24 January 2009, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ Martin, Kočárek (8 June 2010), "Hlídky Dělnické strany sociální spravedlnosti navštívily Ředhošť", tn.cz, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "Chtěl v knize vystěhovat Romy do Indie. Dostal podmínku", aktuálně.cz, 26 October 2011, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ Okamura, Tomio (1 March 2011), "Hon na Bátoru, ostuda politiků a novinářů", iDNES.cz, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ "Roma group wants EU states to admit part of Czech Roma", Prague Daily Monitor, 14 March 2011, retrieved 15 March 2011

- ^ Injustice Renamed: Discrimination in Education of Roma persists in the Czech Republic Amnesty International report, Jan 2010

- ^ "Amnesty says Czech schools still fail Roma Gypsies". BBC News. 13 January 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Roma-politik igen i søgelyset" (in Danish). DR Radio P4. 18 January 2006.

- ^ "France sends Roma Gypsies back to Romania". BBC. 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 21 August 2010. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "France Begins Controversial Roma Deportations". Der Spiegel. 19 August 2010. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Germany Sending Gypsy Refugees Back to Kosovo

- ^ "Egy megdöbbentő gyilkosságsorozat részletei". Index. 25 March 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

- ^ D'Amato, Erik (3 February 2009). "Why Fidesz can't profit from "Gypsy crime"?". Politics.Hu. Retrieved 3 April 2009.

- ^ a b By Cormac O’Keeffe (16 March 2012). "Kidnapped, gang raped, tortured, shot and dumped, but no one cares". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ independent.ie apps (29 January 2012). "Young and vulnerable, her last days spent in fear - Analysis, Opinion". Independent.ie. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b c By Cormac O’Keeffe (16 March 2012). "Kidnapped, gang raped, tortured, shot and dumped, but no one cares". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b independent.ie apps (18 February 2012). "Mark O'Regan witnesses a heart-broken family's grief and reflects on the wider issue of our attitudes to Roma immigrants - Lifestyle". Independent.ie. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b Forde, Killian (16 March 2012). "We must fight Irish prejudice". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Marioara Rostas – a candle-lit vigil. « Pavee Point Travellers' Centre". Paveepoint.ie. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Hooper, John (2 November 2007). "Italian woman's murder prompts expulsion threat to Romanians". London: The Guardian.

- ^ Unknown, Unknown (28 May 2008). "Italy condemned for 'racism wave'". BBC News. BBC.

- ^ a b c d Italy: Court inflames Roma discrimination row The Guardian Retrieved 17 July 2008

- ^ a b "U.N. blasts Italy over Gypsy 'discrimination'". 15 July 2008. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ^ a b Shields, Rachel (6 July 2008). "No blacks, no dogs, no Gypsies". The Independent. London.

- ^ "Gypsies and Irish Travellers: The facts". Commission on Racial Equality (UK).

- ^ "Gypsies". Inside Out - South East. BBC. 19 September 2005.

- ^ The Gypsy Debate: Can Discourse Control? Joanna Richardson 2006 Imprint academic ch 1 p1.

- ^ Craig, Gary (2012). Understanding 'Race' and Ethnicity: Theory, History, Policy, Practice. The Policy Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781847427700.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Andrew MacKay Former Conservative MP for Bracknell". The Work For You.com. mySociety. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "introduction 2.22". Doncaster.gov.uk. 1 December 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "The Council Chamber". Doncaster.gov.uk. 1 December 2006. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Gypsies and Travellers: A strategy for the CRE, 2004 - 2007

- ^ http://travellerstimes.org.uk/downloads%5CTT36_05042009195639.pdf

- ^ Bellamy, Alison (25 April 2011). "Month closure for Leeds traveller arson attack centre - Top Stories". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ "Bosses apologise at 'no travellers' sign at Blackburn Ice Arena (From Lancashire Telegraph)". Lancashiretelegraph.co.uk. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Scottish Affairs, No. 54, Winter 2006 (pp 39-67) Defining Ethnicity in a Cultural and Socio-Legal Context: The Case of Scottish Gypsy-Travellers by Colin Clark http://www.scottishaffairs.org/onlinepub/sa/clark_sa54_winter06.html

- ^ http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/People/Equality/gypsiestravellers/ethnic

- ^ http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2007/12/04093547/1

- ^ http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2007/12/04093547/1

- ^ http://www.bemis.org.uk/resources/gt/scotland/report%20on%20the%20situation%20of%20the%20roma%20community%20in%20govanhill,%20Glasgow.pdf

- ^ http://amnesty.org.uk/uploads/documents/doc_22449.pdf

- ^ Scottish Government (2010) Gypsies/Travellers in Scotland: The Twice Yearly Count - No. 16: July 2009.Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2010/08/18105029/0 and Article 12 research (available from http://www.article12.org/pdf/GYPSY%20TRAVELLER%20NUMBERS%20IN%20THE%20UK.pdf)

- ^ http://amnesty.org.uk/uploads/documents/doc_22449.pdf

- ^ http://amnesty.org.uk/uploads/documents/doc_22449.pdf

- ^ http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Built-Environment/Housing/16342/management/gt/wpstrategy

- ^ http://www.scottish.parliament.uk/S4_ChamberDesk/WA20110727.pdf

- ^ http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/uploaded_files/download_who_do_you_see_publication_english.pdf

- ^ http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/uploaded_files/download_who_do_you_see_publication_english.pdf

- ^ http://www.travellerstimes.org.uk/list.aspx?c=00619ef1-21e2-40aa-8d5e-f7c38586d32f&n=f52bed58-5368-408f-b50f-b543344a1b60

- ^ "Racist attacks on Roma are latest low in North's intolerant history". irishtimes.com. 18 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ "Amnesty International". Amnesty.org.uk. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Morrison, Peter (17/June/2009). "Romanian Gypsies attacked inIreland". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 23 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Protest held over racist attacks". BBC News. 20/June/2009. Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McDonald, Henry (23/June/2009). "Vandals attack Belfast church that sheltered Romanian victims of racism". London: guardian.co.uk,. Archived from the original on 26 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-23.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "Romanians leave NI after attacks". BBC News website. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Eleanor Harding (January 2008). "The eternal minority". New Internationalist. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hannikainen, Lauri; Åkermark, Sia Spiliopoulou (2003). "The non-autonomous minority groups in the Nordic countries". In Clive, Archer; Joenniemi, Pertti (eds.). The Nordic peace. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 171–197. ISBN 978-0-7546-1417-3.

- ^ "Folk er folk-leder sier han har fått flere drapstrusler".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|access date=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.nrk.no/nyheter/norge/1.8244413.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker - Society for Threatened Peoples. "Roma and Ashkali in Kosovo: Persecuted, driven out, poisened". Gfbv.de. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Gesellschaft fuer bedrohte Voelker - Society for Threatened Peoples. "Lead Poisoning Of Roma In Idp Camps In Kosovo". Gfbv.de. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b Email Us (12 April 2012). "Magazine under fire for racist Roma cover - The Irish Times - Thu, Apr 12, 2012". The Irish Times. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ von Andrea Dernbach. "Streit um Roma-Reportage: Raubzüge beim Fotografen - Medien - Tagesspiegel" (in Template:De icon). Tagesspiegel.de. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Anti-Roma front page provokes controversy | Presseurop (English)". Presseurop.eu. Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ a b Kayla Webley, "Hounded in Europe, Roma in the U.S. Keep a Low Profile", Time, October 13, 2010

- ^ The Gypsy Law. How archaic! - The Guide, March 1998.

- ^ Becerra, Hector (30 January 2006). "Gypsies: the Usual Suspects". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|notes=ignored (help) - ^ Dennis Marlock, John Dowling (1994). License To Steal: Traveling Con Artists: Their Games, Their Rules, Your Money. Paladin Press. ISBN 978-0-87364-751-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Real Stories From Victims Who've Been Scammed". gypsypsychicscams.com. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Feher, Gyorgy. 1993. Struggling for Ethnic Identity: The Gypsies of Hungary. Library of Congress Card Catalogue: USA.

- ^ a b Template:Cs icon Janoušek, Artur (18 September 2007), "Hrůza Ústeckého kraje: sídliště Chanov", iDnes.cz, retrieved 13 March 2011

- ^ Template:Cs icon ČTK (23 June 2006), "V Chanově se bude bourat i druhý vybydlený panelák", ceskenoviny.cz, Czech News Agency (published 23 June), retrieved 13 March 2011

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) - ^ Template:Cs icon Slížová, Radka (25 February 2010), "Chanov jde do lepších časů", sedmicka.cz, retrieved 13 March 2011

- ^ Template:Cs icon Prokop, Dan (28. September, 2008). "Košice zbourají "vybydlené" paneláky na romském sídlišti Luník". idnes.cz. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Sk icon "LUNÍK IX.: Bývanie na sídlisku je kritické, obyvateľom zriadili konto na pomoc". tvnoviny.sk. 18 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Sk icon Teichmanová, Ladislava. "Na Luníku IX a v Demeteri dlhujú za vodu 133 000 €". webnoviny.sk. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Template:Cs icon ČTK (5 May 2005). "Na košickém romském sídlišti Luník IX. zase teče voda". romove.radio.cz. Archived from the original on 6 March 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Environmental Justice: Listening to Women and Children" (PDF). Environmental Health.

- ^ a b c Template:Citation last=Harper

- ^ {{citation Last=Stegar | first=Tamara | title= Articulating the Basis for Promoting Environmental Justice in Central and Eastern Europe | date=8 May 2008 | url= http://www.liebertonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1089/env.2008.0501}}

- ^ Maida, Carl A. 2007. Sustainability and Communities of Place. Berghahn Books

- ^ Rights group files complaint against 'Borat' in Germany[dead link]