Circulatory system: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 120.28.223.198 to version by 121.54.34.88. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1393113) (Bot) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the organ system|the band|Circulatory System|transport in plants|Vascular tissue}} |

|||

The circulatory system is made up of the vessels and the muscles that help and control the flow of the blood around the body. This process is called circulation. The main parts of the system are the heart, arteries, capillaries and veins. |

|||

{{refimprove|date=July 2012}} |

|||

{{Infobox Anatomy | |

|||

Name = Circulatory system | |

|||

Latin = systema cardiovasculare | |

|||

GraySubject = | |

|||

GrayPage = | |

|||

Image = Circulatory System en.svg | |

|||

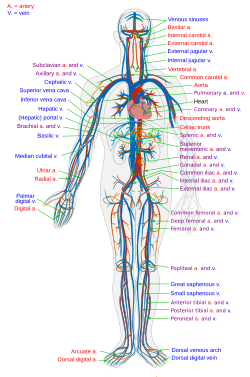

Caption = The human circulatory system (simplified). Red indicates oxygenated blood, blue indicates deoxygenated.<br>(Not depicted are the intricate network of [[capillary|capillaries]], as well as the entire [[lymphatic system]].)| |

|||

Image2 = | |

|||

Caption2 = | |

|||

Precursor = | |

|||

System = | |

|||

Artery = | |

|||

Vein = | |

|||

Nerve = | |

|||

Lymph = | |

|||

MeshName = | |

|||

MeshNumber = | |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''circulatory system''' is an [[Biological system|organ system]] that passes nutrients (such as [[amino acids]], [[electrolytes]] and [[lymph]]), gases, [[hormone]]s, [[blood]] cells, etc. to and from [[cells (biology)|cells]] in the body to help fight diseases, stabilize [[Thermoregulation|body temperature]] and [[pH]], and to maintain [[homeostasis]]. |

|||

This system may be seen strictly as a blood distribution network, but some consider the circulatory system as composed of the '''cardiovascular system''', which distributes blood,<ref>{{DorlandsDict|eight/000105264|cardiovascular system}}</ref> and the '''[[lymphatic system]]''',<ref>{{DorlandsDict|nine/000951445|circulatory system}}</ref> which returns excess [[capillary filtration|filtered]] [[blood plasma]] from the [[interstitial fluid]] (between cells) as [[lymph]]. While humans, as well as other [[vertebrates]], have a closed cardiovascular system (meaning that the blood never leaves the network of [[arteries]], [[veins]] and [[capillaries]]), some [[invertebrate]] groups have an open cardiovascular system. The {{clarify span|most primitive animal [[phylum|phyla]]|date=October 2012}} lack circulatory systems. The lymphatic system, on the other hand, is an open system providing an accessory route for excess interstitial fluid to get returned to the blood.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=I9qH3eZ1pP0C&pg=PT401#v=onepage&q&f=false Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems, by Lauralee Sherwood]</ref> |

|||

As blood begins to circulate, it leaves the heart from the left ventricle and goes into the aorta. The aorta is the largest artery in the body. The blood leaving the aorta is full of oxygen. This is important for the cells in the brain and the body to do their work. The oxygen rich blood travels throughout the body in its system of arteries into the smallest arterioles. |

|||

Two types of fluids move through the circulatory system: blood and lymph. Lymph is essentially recycled [[blood plasma]] after it has been filtered from the [[blood cells]] and returned to the lymphatic system. The blood, [[heart]], and blood vessels form the cardiovascular (from Latin words meaning 'heart'-'vessel') system. The lymph, lymph nodes, and lymph vessels form the [[lymphatic system]]. The cardiovascular system and the lymphatic system collectively make up the circulatory system. |

|||

On its way back to the heart, the blood travels through a system of veins. As it reaches the lungs, the carbon dioxide (a waste product) is removed from the blood and replace with fresh oxygen that we have inhaled through the lungs. |

|||

==Human cardiovascular system== |

|||

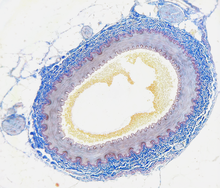

[[File:Artery.png|thumb|Cross section of a human artery]] |

|||

The essential components of the human cardiovascular system are the [[heart]], [[blood]], and [[blood vessel]]s.<ref>{{MeshName|Cardiovascular+System}}</ref> It includes: the [[pulmonary circulation]], a "loop" through the [[lung]]s where blood is oxygenated; and the [[systemic circulation]], a "loop" through the rest of the body to provide [[oxygenate]]d blood. An average adult contains five to six quarts (roughly 4.7 to 5.7 liters) of blood, accounting for approximately 7% of their total body weight.<ref>{{cite web|last=Pratt|first=Rebecca|title=Cardiovascular System: Blood|url=https://app.anatomyone.com/systemic/cardiovascular-system/blood|work=AnatomyOne|publisher=Amirsys, Inc.|accessdate=10/12/12}}</ref> Blood consists of [[blood plasma|plasma]], [[red blood cells]], [[white blood cells]], and [[platelets]]. Also, the [[digestive system]] works with the circulatory system to provide the nutrients the system needs to keep the [[heart]] pumping. |

|||

===Pulmonary circulation=== |

|||

{{Main|Pulmonary circulation}} |

|||

The pulmonary circulatory system is the portion of the cardiovascular system in which [[oxygen]]-depleted [[blood]] is pumped away from the heart, via the [[pulmonary artery]], to the [[lungs]] and returned, oxygenated, to the heart via the [[pulmonary vein]]. |

|||

Oxygen deprived blood from the [[vena cava]], enters the right atrium of the heart and flows through the [[tricuspid valve]] (right atrioventricular valve) into the right ventricle, from which it is then pumped through the [[pulmonary semilunar valve]] into the pulmonary artery to the lungs. Gas exchange occurs in the lungs, whereby {{CO2|link=yes}} is released from the blood, and oxygen is absorbed. The pulmonary vein returns the now oxygen-rich blood to the heart. |

|||

===Systemic circulation=== |

|||

{{Main|Systemic circulation}} |

|||

Systemic circulation is the circulation of the blood to all parts of the body except the lungs. Systemic circulation is the portion of the cardiovascular system which transports oxygenated blood away from the heart, to the rest of the body, and returns oxygen-depleted blood back to the heart. Systemic circulation is, distance-wise, much longer than pulmonary circulation, transporting blood to every part of the body. |

|||

[[File:Diagram of the human heart (cropped).svg|300px|thumb|View from the front, which means the right side of the heart is on the left of the diagram (and vice-versa)]] |

|||

===Coronary circulation=== |

|||

{{Main|Coronary circulation}} |

|||

The coronary circulatory system provides a blood supply to the heart. As it provides oxygenated blood to the heart, it is by definition a part of the systemic circulatory system. The artery coronary sinus opens up into the right atrium, and the back flow of blood through its opening during atricular systole is guarded by the thebasian valve. |

|||

===Heart=== |

|||

{{Main|Human heart}} |

|||

The heart pumps oxygenated blood to the body and deoxygenated blood to the lungs. In the human [[heart]] there is one [[atrium (heart)|atrium]] and one [[Ventricle (heart)|ventricle]] for each circulation, and with both a systemic and a pulmonary circulation there are four chambers in total: [[left atrium]], [[left ventricle]], [[right atrium]] and [[right ventricle]]. The right atrium is the upper chamber of the right side of the heart. The blood that is returned to the right atrium is deoxygenated (poor in oxygen) and passed into the right ventricle to be pumped through the pulmonary artery to the lungs for re-oxygenation and removal of carbon dioxide. The left atrium receives newly oxygenated blood from the lungs as well as the pulmonary vein which is passed into the strong left ventricle to be pumped through the aorta to the different organs of the body. |

|||

===Closed cardiovascular system=== |

|||

The cardiovascular systems of humans are closed, meaning that the blood never leaves the network of [[blood vessels]]. In contrast, oxygen and nutrients diffuse across the blood vessel layers and enters [[interstitial fluid]], which carries oxygen and nutrients to the target cells, and carbon dioxide and wastes in the opposite direction. The other component of the circulatory system, the [[lymphatic system]], is not closed. |

|||

===Oxygen transportation=== |

|||

{{Main|Blood#Oxygen transport}} |

|||

About 98.5% of the [[oxygen]] in a sample of arterial blood in a healthy human breathing air at sea-level pressure is chemically combined with [[hemoglobin]] molecules. About 1.5% is physically dissolved in the other blood liquids and not connected to hemoglobin. The hemoglobin molecule is the primary transporter of oxygen in [[mammal]]s and many other species. |

|||

[[Image:Erytrocyte deoxy to oxy v0.7.gif|thumb|An animation of a typical human red blood cell cycle in the circulatory system. This animation occurs at real time (20 seconds of cycle) and shows the red blood cell deform as it enters capillaries, as well as changing color as it alternates in states of oxygenation along the circulatory system.]] |

|||

[[File:Arteria-lusoria MRA MIP.gif|thumb|[[Magnetic resonance angiography]] of [[aberrant subclavian artery]]]] |

|||

=== Development === |

|||

The development of the circulatory system initially occurs by the process of [[vasculogenesis]]. The human arterial and venous systems develop from different embryonic areas. While the arterial system develops mainly from the [[aortic arches]], the venous system arises from three bilateral veins during weeks 4 - 8 of [[Human development (biology)|human development]]. |

|||

==== Arterial development ==== |

|||

{{Main|Aortic arches}} |

|||

The human arterial system originate from the aortic arches and from the [[dorsal aortae]] starting from week 4 of human development. Aortic arch 1 almost completely regresses except to form the [[maxillary artery|maxillary arteries]]. Aortic arch 2 also completely regresses except to form the [[stapedial artery|stapedial arteries]]. The definitive formation of the arterial system arise from aortic arches 3, 4 and 6. While aortic arch 5 completely regresses. |

|||

The dorsal aortae are initially bilateral and then fuse to form the definitive dorsal aorta. Approximately 30 posterolateral branches arise off the aorta and will form the [[intercostal arteries]], upper and lower extremity arteries, lumbar arteries and the lateral sacral arteries. The lateral branches of the aorta form the definitive [[renal artery|renal]], [[Inferior suprarenal artery|suprarrenal]] and [[gonadal artery|gonadal arteries]]. Finally, the ventral branches of the aorta consist of the [[vitelline arteries]] and [[umbilical arteries]]. The vitelline arteries form the [[celiac artery|celiac]], [[superior mesenteric artery|superior]] and [[inferior mesenteric artery|inferior mesenteric arteries]] of the gastrointestinal tract. After birth, the umbilical arteries will form the [[internal iliac artery|internal iliac arteries]]. |

|||

==== Venous development ==== |

|||

The human venous system develops mainly from the [[vitelline vein]]s, the [[umbilical vein]]s and the [[cardinal veins]], all of which empty into the [[sinus venosus]]. |

|||

===Measurement techniques=== |

|||

* [[Electrocardiogram]]—for cardiac electrophysiology |

|||

* [[Sphygmomanometer]] and [[stethoscope]]—for blood pressure |

|||

* [[Pulse meter]]—for cardiac function (heart rate, rhythm, dropped beats) |

|||

* [[Pulse]]—commonly used to determine the heart rate in absence of certain cardiac pathologies |

|||

* [[Heart rate variability]]—used to measure variations of time intervals between heart beats |

|||

* [[Nail (anatomy)|Nail]] bedwedge pressure or in older animal experiments. |

|||

===Health and disease=== |

|||

{{Main|Cardiovascular disease}} |

|||

{{Main|Congenital heart defect}} |

|||

==Nonhuman== |

|||

=== Other vertebrates === |

|||

[[File:Two chamber heart.svg|thumb|Two-chambered heart of a fish]] |

|||

The circulatory systems of all [[vertebrate]]s, as well as of [[annelid]]s (for example, [[earthworm]]s) and [[cephalopod]]s ([[squid]]s, [[octopus]]es and relatives) are ''closed'', just as in humans. Still, the systems of [[fish]], [[amphibian]]s, [[reptile]]s, and [[bird]]s show various stages of the [[evolution]] of the circulatory system. |

|||

In fish, the system has only one circuit, with the blood being pumped through the capillaries of the [[gill]]s and on to the capillaries of the body tissues. This is known as ''single cycle'' circulation. The heart of fish is therefore only a single pump (consisting of two chambers). |

|||

In amphibians and most reptiles, a [[double circulatory system]] is used, but the heart is not always completely separated into two pumps. Amphibians have a three-chambered heart. |

|||

In reptiles, the [[ventricular septum]] of the heart is incomplete and the [[pulmonary artery]] is equipped with a [[sphincter muscle]]. This allows a second possible route of blood flow. Instead of blood flowing through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, the sphincter may be contracted to divert this blood flow through the incomplete ventricular septum into the [[left ventricle]] and out through the [[aorta]]. This means the blood flows from the capillaries to the heart and back to the capillaries instead of to the lungs. This process is useful to [[ectothermic]] (cold-blooded) animals in the regulation of their body temperature. |

|||

Birds and mammals show complete separation of the heart into two pumps, for a total of four heart chambers; it is thought{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} that the four-chambered heart of birds evolved independently from that of mammals. |

|||

===Open circulatory system=== |

|||

The open circulatory system is a system in which a fluid in a cavity called the hemocoel bathes the organs directly with oxygen and nutrients and there is no distinction between [[blood]] and [[interstitial fluid]]; this combined fluid is called [[hemolymph]] or haemolymph.<ref>{{cite web|last=Bailey|first=Regina|title=Circulatory System|url=http://biology.about.com/od/organsystems/a/circulatorysystem.htm}}</ref> Muscular movements by the animal during [[Animal locomotion|locomotion]] can facilitate hemolymph movement, but diverting flow from one area to another is limited. When the [[heart]] relaxes, blood is drawn back toward the heart through open-ended pores (ostia). |

|||

Hemolymph fills all of the interior hemocoel of the body and surrounds all [[cell (biology)|cell]]s. Hemolymph is composed of [[water]], [[inorganic chemistry|inorganic]] [[Salt (chemistry)|salt]]s (mostly [[Sodium|Na<sup>+</sup>]], [[Chlorine|Cl<sup>-</sup>]], [[Potassium|K<sup>+</sup>]], [[Magnesium|Mg<sup>2+</sup>]], and [[Calcium|Ca<sup>2+</sup>]]), and [[organic chemistry|organic compounds]] (mostly [[carbohydrate]]s, [[protein]]s, and [[lipid]]s). The primary oxygen transporter molecule is [[hemocyanin]]. |

|||

There are free-floating cells, the [[hemocyte]]s, within the hemolymph. They play a role in the arthropod [[immune system]]. |

|||

===Absence of circulatory system=== |

|||

[[File:Helicometra.jpg|thumb|Flatworms, such as this ''[[Helicometra]]'' sp., lack specialized circulatory organs]] |

|||

Circulatory systems are absent in some animals, including [[flatworms]] (phylum [[Platyhelminthes]]). Their [[body cavity]] has no lining or enclosed fluid. Instead a muscular [[pharynx]] leads to an extensively branched [[digestive system]] that facilitates direct [[diffusion]] of nutrients to all cells. The flatworm's dorso-ventrally flattened body shape also restricts the distance of any cell from the digestive system or the exterior of the organism. [[Oxygen]] can diffuse from the surrounding [[water]] into the cells, and [[carbon dioxide]] can diffuse out. Consequently every cell is able to obtain nutrients, water and oxygen without the need of a transport system. |

|||

Some animals, such as [[jellyfish]], have more extensive branching from their gastrovascular cavity (which functions as both a place of digestion and a form of circulation), this branching allows for bodily fluids to reach the outer layers, since the digestion begins in the inner layers. |

|||

==History of discovery== |

|||

The earliest known writings on the circulatory system are found in the [[Ebers Papyrus]] (16th century BCE), an [[Ancient Egyptian medicine|ancient Egyptian medical papyrus]] containing over 700 prescriptions and remedies, both physical and spiritual. In the [[papyrus]], it acknowledges the connection of the heart to the arteries. The Egyptians thought air came in through the mouth and into the lungs and heart. From the heart, the air travelled to every member through the arteries. Although this concept of the circulatory system is greatly flawed, it represents one of the earliest accounts of scientific thought. |

|||

In the 6th century BCE, the knowledge of circulation of vital fluids through the body was known to the [[Ayurveda|Ayurvedic]] physician [[Sushruta]] in [[History of India|ancient India]].<ref name=Dwivedi&Dwivedi07/> He also seems to have possessed knowledge of the [[arteries]], described as 'channels' by Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007).<ref name=Dwivedi&Dwivedi07>Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). [http://medind.nic.in/iae/t07/i4/iaet07i4p243.pdf ''History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence'']. [[National Informatics Centre|National Informatics Centre (Government of India)]].</ref> The [[Heart valve|valves of the heart]] were discovered by a physician of the [[Hippocrates|Hippocratean]] school around the 4th century BCE. However their function was not properly understood then. Because blood pools in the veins after death, arteries look empty. Ancient anatomists assumed they were filled with air and that they were for transport of air. |

|||

The [[Ancient Greek Medicine|Greek physician]], [[Herophilus]], distinguished veins from arteries but thought that the [[pulse]] was a property of arteries themselves. Greek anatomist [[Erasistratus]] observed that arteries that were cut during life bleed. He ascribed the fact to the phenomenon that air escaping from an artery is replaced with blood that entered by very small vessels between veins and arteries. Thus he apparently postulated capillaries but with reversed flow of blood.<ref>[http://www.scienceclarified.com/Al-As/Anatomy.html Anatomy - History of anatomy]</ref> |

|||

In 2nd century AD [[Rome]], the [[Ancient Greek Medicine|Greek]] physician [[Galen]] knew that blood vessels carried blood and identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Growth and energy were derived from venous blood created in the liver from chyle, while arterial blood gave vitality by containing pneuma (air) and originated in the heart. Blood flowed from both creating organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed and there was no return of blood to the heart or liver. The heart did not pump blood around, the heart's motion sucked blood in during diastole and the blood moved by the pulsation of the arteries themselves. |

|||

Galen believed that the arterial blood was created by venous blood passing from the left ventricle to the right by passing through 'pores' in the interventricular septum, air passed from the lungs via the pulmonary artery to the left side of the heart. As the arterial blood was created 'sooty' vapors were created and passed to the lungs also via the pulmonary artery to be exhaled. |

|||

In 1025, ''[[The Canon of Medicine]]'' by the [[Ancient Iranian Medicine|Persian physician]], [[Avicenna]], "erroneously accepted the Greek notion regarding the existence of a hole in the ventricular septum by which the blood traveled between the ventricles." Despite this, Avicenna "correctly wrote on the [[cardiac cycle]]s and valvular function", and "had a vision of blood circulation" in his ''Treatise on Pulse''.<ref>{{citation|title=Vasovagal syncope in the Canon of Avicenna: The first mention of carotid artery hypersensitivity|last=Mohammadali M. Shojaa, R. Shane Tubbsb, Marios Loukasc|first=Majid Khalilid, Farid Alakbarlie, Aaron A. Cohen-Gadola|journal=International Journal of Cardiology|volume=134|issue=3|date=29 May 2009|publisher=[[Elsevier]]|doi=10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.02.035|pages=297–301|pmid=19332359|last2=Tubbs|first2=RS|last3=Loukas|first3=M|last4=Khalili|first4=M|last5=Alakbarli|first5=F|last6=Cohen-Gadol|first6=AA}}</ref>{{Verify source|date=September 2010}} While also refining Galen's erroneous theory of the pulse, Avicenna provided the first correct explanation of pulsation: "Every beat of the pulse comprises two movements and two pauses. Thus, expansion : pause : contraction : pause. [...] The pulse is a movement in the heart and arteries ... which takes the form of alternate expansion and contraction."<ref name=Hajar>Rachel Hajar (1999), "The Greco-Islamic Pulse", ''Heart Views'' '''1''' (4): 136-140 [138]</ref>{{Verify source|date=September 2010}} |

|||

In 1242, the [[Medicine in medieval Islam|Arabian physician]], [[Ibn al-Nafis]], became the first person to accurately describe the process of [[pulmonary circulation]], for which he is sometimes considered the father of [[Cardiovascular physiology|circulatory physiology]].<ref>Chairman's Reflections (2004), "[http://www.hmc.org.qa/heartviews/VOL5NO2/special_section.htm Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting]", ''Heart Views'' '''5''' (2), p. 74-85 [80].</ref>{{Failed verification|date=June 2010}} Ibn al-Nafis stated in his ''Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon'': |

|||

<blockquote>"...the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa ([[pulmonary artery]]) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa ([[pulmonary vein]]) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit..."</blockquote> |

|||

In addition, Ibn al-Nafis had an insight into what would become a larger theory of the [[capillary]] circulation. He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (''manafidh'' in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein," a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years.<ref>{{citation|title=Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age|first=John B.|last=West|journal=Journal of Applied Physiology|volume=105|pages=1877–80|date=October 9, 2008|doi=10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008|pmid=18845773|issue=6|pmc=2612469}}</ref> Ibn al-Nafis' theory, however, was confined to blood transit in the lungs and did not extend to the entire body. |

|||

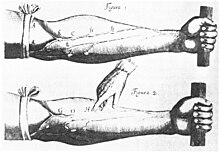

[[File:William Harvey ( 1578-1657) Venenbild.jpg|thumb|Image of veins from [[William Harvey]]'s ''Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus'']] |

|||

[[Michael Servetus]] was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation, although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. He firstly described it in the "Manuscript of Paris"<ref>2011 “The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus”, (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra, 607 pp, 64 of them illustrations, p 215-228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)</ref><ref>[http://www.michaelservetusresearch.com/ENGLISH/works.html Michael Servetus Research] Study with graphical proof on the Manuscript of Paris and many other manuscripts and new works by Servetus</ref> (near 1546), but this work was never published. And later he published this description, but in a theological treatise, ''Christianismi Restitutio'', not in a book on medicine. Only three copies of the book survived, the rest were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities. Finally [[William Harvey]], a pupil of [[Hieronymus Fabricius]] (who had earlier described the valves of the veins without recognizing their function), performed a sequence of experiments, and published ''Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus'' in 1628, which "demonstrated that there had to be a direct connection between the venous and arterial systems throughout the body, and not just the lungs. Most importantly, he argued that the beat of the heart produced a continuous circulation of blood through minute connections at the extremities of the body. This is a conceptual leap that was quite different from Ibn al-Nafis' refinement of the anatomy and bloodflow in the heart and lungs."<ref>Peter E. Pormann and E. Savage Smith, ''Medieval Islamic medicine'' Georgetown University, Washington DC, 2007, p. 48.</ref> This work, with its essentially correct exposition, slowly convinced the medical world. However, Harvey was not able to identify the capillary system connecting arteries and veins; these were later discovered by [[Marcello Malpighi]] in 1661. |

|||

In 1956, [[André Frédéric Cournand]], [[Werner Forssmann]] and [[Dickinson W. Richards]] were awarded the [[List of Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel Prize]] in Medicine "for their discoveries concerning [[heart catheterization]] and pathological changes in the circulatory system."<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| url = http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1956/index.html |

|||

| title = The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1956 |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-07-28 |

|||

| publisher = Nobel Foundation |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

<div style="-moz-column-count:3; column-count:3;"> |

|||

*[[Microcirculation]] |

|||

* [[Cardiology]] |

|||

* [[Lymphatic system]] |

|||

* [[Blood vessels]] |

|||

* [[Innate heat]] |

|||

* [[Cardiac muscle]] |

|||

* [[Major systems of the human body]] |

|||

* [[Heart]] |

|||

* [[Amato Lusitano]] |

|||

* [[William Harvey]] |

|||

</div> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{commons category|Circulatory system}} |

|||

* [http://www.healthmean.com/bodysystems/the-circulatory-system/ The Circulatory System Article] |

|||

* [http://www.emc.maricopa.edu/faculty/farabee/BIOBK/BioBookcircSYS.html The Circulatory System] |

|||

* [http://www.nature.com/ncpcardio/index.html NCP Cardiovascular Medicine] A Journal Covering Clinical Cardiovascular Medicine |

|||

* Reiber C. L. & McGaw I. J. (2009). "A Review of the "Open" and "Closed" Circulatory Systems: New Terminology for Complex Invertebrate Circulatory Systems in Light of Current Findings". ''[[International Journal of Zoology]]'' '''2009''': 8 pages. {{doi|10.1155/2009/301284}}. |

|||

* Patwardhan K. The history of the discovery of blood circulation: unrecognized contributions of Ayurveda masters. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012 Jun;36(2):77-82. [http://advan.physiology.org/content/36/2/77.long] |

|||

*[http://www.innerbody.com/image/cardov.html Cardiovascular Pedagogical Simulation] |

|||

* [http://www.michaelservetusresearch.com/ENGLISH/works.html Michael Servetus Research] Study on the Manuscript of Paris by Servetus (1546 description of the Pulmonary Circulation) |

|||

{{organ systems}} |

|||

{{Heart}} |

|||

{{Arteries and veins}} |

|||

{{Cardiovascular physiology}} |

|||

{{Development of circulatory system}} |

|||

{{Circulatory system pathology}} |

|||

{{Lymphatic flow}} |

|||

<!-- [[malay:Sistem kardiovaskular]] --> |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Circulatory System}} |

|||

[[Category:Circulatory system| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Exercise physiology]] |

|||

{{Link FA|de}} |

|||

[[ar:جهاز الدوران]] |

|||

[[an:Sistema circulatorio]] |

|||

[[ast:Sistema cardiovascular]] |

|||

[[bn:সংবহন তন্ত্র]] |

|||

[[zh-min-nan:Sûn-khoân hē-thóng]] |

|||

[[be:Кровазварот]] |

|||

[[be-x-old:Кровазварот]] |

|||

[[bg:Кръвообращение]] |

|||

[[bs:Krvotok]] |

|||

[[ca:Sistema circulatori]] |

|||

[[cs:Oběhová soustava]] |

|||

[[cy:System gylchredol]] |

|||

[[da:Blodkredsløbet]] |

|||

[[de:Blutkreislauf]] |

|||

[[dv:ލޭދައުރުކުރާ ނިޒާމް]] |

|||

[[el:Καρδιαγγειακό σύστημα]] |

|||

[[es:Aparato circulatorio]] |

|||

[[eo:Kardiovaskula sistemo]] |

|||

[[eu:Zirkulazio-aparatu]] |

|||

[[fa:دستگاه گردش خون]] |

|||

[[hif:Circulatory system]] |

|||

[[fr:Circulation sanguine]] |

|||

[[gl:Aparato circulatorio]] |

|||

[[gu:રુધિરાભિસરણ તંત્ર]] |

|||

[[hak:Sùn-fàn Hì-thúng]] |

|||

[[ko:순환계통]] |

|||

[[hi:परिसंचरण तंत्र]] |

|||

[[hr:Krvožilni sustav]] |

|||

[[id:Sistem kardiovaskular]] |

|||

[[is:Blóðrásarkerfi]] |

|||

[[it:Apparato circolatorio]] |

|||

[[he:מחזור הדם]] |

|||

[[jv:Sistem kardiovaskular]] |

|||

[[kn:ರಕ್ತಪರಿಚಲನೆಯ ವ್ಯವಸ್ಥೆ]] |

|||

[[pam:Circulatory system]] |

|||

[[ku:Sîstema gera xwînê]] |

|||

[[la:Apparatus circulatorius]] |

|||

[[lv:Asinsrites orgānu sistēma]] |

|||

[[lt:Kraujotakos sistema]] |

|||

[[hu:Vérkeringés]] |

|||

[[mk:Циркулаторен систем]] |

|||

[[ml:രക്തചംക്രമണവ്യൂഹം]] |

|||

[[my:နှလုံး သွေးကြောစနစ်]] |

|||

[[nl:Hart en vaatstelsel]] |

|||

[[ja:循環器]] |

|||

[[no:Sirkulasjonssystem]] |

|||

[[nn:Kretsløpssystemet]] |

|||

[[oc:Sistèma circulatòri]] |

|||

[[pnb:سرکولیٹری پربندھ]] |

|||

[[km:ប្រដាប់របត់ឈាម]] |

|||

[[nds:Bloodkreisloop]] |

|||

[[pl:Układ krwionośny człowieka]] |

|||

[[pt:Sistema circulatório]] |

|||

[[ro:Aparat cardiovascular]] |

|||

[[qu:Sirk'a llika]] |

|||

[[ru:Сердечно-сосудистая система]] |

|||

[[sah:Хаан эргиирэ]] |

|||

[[sq:Sistemi i qarkullimit të gjakut]] |

|||

[[simple:Circulatory system]] |

|||

[[sk:Obehová sústava]] |

|||

[[sl:Obtočila]] |

|||

[[so:Habdhiska Wareega Dhiiga]] |

|||

[[ckb:کۆئەندامی خوێن سووڕان]] |

|||

[[ckb:کۆئەندامی سووڕان]] |

|||

[[sr:Крвни систем]] |

|||

[[sh:Cirkulatorni sistem]] |

|||

[[fi:Verenkierto]] |

|||

[[sv:Hjärt-kärlsystemet]] |

|||

[[tl:Sistemang sirkulatoryo]] |

|||

[[ta:சுற்றோட்டத் தொகுதி]] |

|||

[[tt:Кан әйләнеше]] |

|||

[[te:ప్రసరణ వ్యవస్థ]] |

|||

[[th:ระบบไหลเวียนโลหิต]] |

|||

[[tr:Dolaşım sistemi]] |

|||

[[uk:Кровообіг]] |

|||

[[ur:قلبی وِ عائی نظام]] |

|||

[[ug:ئايلىنىش سىستېمىسى]] |

|||

[[vi:Hệ tuần hoàn]] |

|||

[[war:Sistema sirkulatoryo]] |

|||

[[yi:בלוט צירקולאציע]] |

|||

[[zh:循环系统]] |

|||

Revision as of 11:51, 11 December 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

| Circulatory system | |

|---|---|

The human circulatory system (simplified). Red indicates oxygenated blood, blue indicates deoxygenated. (Not depicted are the intricate network of capillaries, as well as the entire lymphatic system.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | systema cardiovasculare |

| MeSH | D002319 |

| TA98 | A12.0.00.000 |

| TA2 | 3891 |

| FMA | 7161 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The circulatory system is an organ system that passes nutrients (such as amino acids, electrolytes and lymph), gases, hormones, blood cells, etc. to and from cells in the body to help fight diseases, stabilize body temperature and pH, and to maintain homeostasis.

This system may be seen strictly as a blood distribution network, but some consider the circulatory system as composed of the cardiovascular system, which distributes blood,[1] and the lymphatic system,[2] which returns excess filtered blood plasma from the interstitial fluid (between cells) as lymph. While humans, as well as other vertebrates, have a closed cardiovascular system (meaning that the blood never leaves the network of arteries, veins and capillaries), some invertebrate groups have an open cardiovascular system. The most primitive animal phyla[clarify] lack circulatory systems. The lymphatic system, on the other hand, is an open system providing an accessory route for excess interstitial fluid to get returned to the blood.[3]

Two types of fluids move through the circulatory system: blood and lymph. Lymph is essentially recycled blood plasma after it has been filtered from the blood cells and returned to the lymphatic system. The blood, heart, and blood vessels form the cardiovascular (from Latin words meaning 'heart'-'vessel') system. The lymph, lymph nodes, and lymph vessels form the lymphatic system. The cardiovascular system and the lymphatic system collectively make up the circulatory system.

Human cardiovascular system

The essential components of the human cardiovascular system are the heart, blood, and blood vessels.[4] It includes: the pulmonary circulation, a "loop" through the lungs where blood is oxygenated; and the systemic circulation, a "loop" through the rest of the body to provide oxygenated blood. An average adult contains five to six quarts (roughly 4.7 to 5.7 liters) of blood, accounting for approximately 7% of their total body weight.[5] Blood consists of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets. Also, the digestive system works with the circulatory system to provide the nutrients the system needs to keep the heart pumping.

Pulmonary circulation

The pulmonary circulatory system is the portion of the cardiovascular system in which oxygen-depleted blood is pumped away from the heart, via the pulmonary artery, to the lungs and returned, oxygenated, to the heart via the pulmonary vein.

Oxygen deprived blood from the vena cava, enters the right atrium of the heart and flows through the tricuspid valve (right atrioventricular valve) into the right ventricle, from which it is then pumped through the pulmonary semilunar valve into the pulmonary artery to the lungs. Gas exchange occurs in the lungs, whereby CO2 is released from the blood, and oxygen is absorbed. The pulmonary vein returns the now oxygen-rich blood to the heart.

Systemic circulation

Systemic circulation is the circulation of the blood to all parts of the body except the lungs. Systemic circulation is the portion of the cardiovascular system which transports oxygenated blood away from the heart, to the rest of the body, and returns oxygen-depleted blood back to the heart. Systemic circulation is, distance-wise, much longer than pulmonary circulation, transporting blood to every part of the body.

Coronary circulation

The coronary circulatory system provides a blood supply to the heart. As it provides oxygenated blood to the heart, it is by definition a part of the systemic circulatory system. The artery coronary sinus opens up into the right atrium, and the back flow of blood through its opening during atricular systole is guarded by the thebasian valve.

Heart

The heart pumps oxygenated blood to the body and deoxygenated blood to the lungs. In the human heart there is one atrium and one ventricle for each circulation, and with both a systemic and a pulmonary circulation there are four chambers in total: left atrium, left ventricle, right atrium and right ventricle. The right atrium is the upper chamber of the right side of the heart. The blood that is returned to the right atrium is deoxygenated (poor in oxygen) and passed into the right ventricle to be pumped through the pulmonary artery to the lungs for re-oxygenation and removal of carbon dioxide. The left atrium receives newly oxygenated blood from the lungs as well as the pulmonary vein which is passed into the strong left ventricle to be pumped through the aorta to the different organs of the body.

Closed cardiovascular system

The cardiovascular systems of humans are closed, meaning that the blood never leaves the network of blood vessels. In contrast, oxygen and nutrients diffuse across the blood vessel layers and enters interstitial fluid, which carries oxygen and nutrients to the target cells, and carbon dioxide and wastes in the opposite direction. The other component of the circulatory system, the lymphatic system, is not closed.

Oxygen transportation

About 98.5% of the oxygen in a sample of arterial blood in a healthy human breathing air at sea-level pressure is chemically combined with hemoglobin molecules. About 1.5% is physically dissolved in the other blood liquids and not connected to hemoglobin. The hemoglobin molecule is the primary transporter of oxygen in mammals and many other species.

Development

The development of the circulatory system initially occurs by the process of vasculogenesis. The human arterial and venous systems develop from different embryonic areas. While the arterial system develops mainly from the aortic arches, the venous system arises from three bilateral veins during weeks 4 - 8 of human development.

Arterial development

The human arterial system originate from the aortic arches and from the dorsal aortae starting from week 4 of human development. Aortic arch 1 almost completely regresses except to form the maxillary arteries. Aortic arch 2 also completely regresses except to form the stapedial arteries. The definitive formation of the arterial system arise from aortic arches 3, 4 and 6. While aortic arch 5 completely regresses.

The dorsal aortae are initially bilateral and then fuse to form the definitive dorsal aorta. Approximately 30 posterolateral branches arise off the aorta and will form the intercostal arteries, upper and lower extremity arteries, lumbar arteries and the lateral sacral arteries. The lateral branches of the aorta form the definitive renal, suprarrenal and gonadal arteries. Finally, the ventral branches of the aorta consist of the vitelline arteries and umbilical arteries. The vitelline arteries form the celiac, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries of the gastrointestinal tract. After birth, the umbilical arteries will form the internal iliac arteries.

Venous development

The human venous system develops mainly from the vitelline veins, the umbilical veins and the cardinal veins, all of which empty into the sinus venosus.

Measurement techniques

- Electrocardiogram—for cardiac electrophysiology

- Sphygmomanometer and stethoscope—for blood pressure

- Pulse meter—for cardiac function (heart rate, rhythm, dropped beats)

- Pulse—commonly used to determine the heart rate in absence of certain cardiac pathologies

- Heart rate variability—used to measure variations of time intervals between heart beats

- Nail bedwedge pressure or in older animal experiments.

Health and disease

Nonhuman

Other vertebrates

The circulatory systems of all vertebrates, as well as of annelids (for example, earthworms) and cephalopods (squids, octopuses and relatives) are closed, just as in humans. Still, the systems of fish, amphibians, reptiles, and birds show various stages of the evolution of the circulatory system.

In fish, the system has only one circuit, with the blood being pumped through the capillaries of the gills and on to the capillaries of the body tissues. This is known as single cycle circulation. The heart of fish is therefore only a single pump (consisting of two chambers).

In amphibians and most reptiles, a double circulatory system is used, but the heart is not always completely separated into two pumps. Amphibians have a three-chambered heart.

In reptiles, the ventricular septum of the heart is incomplete and the pulmonary artery is equipped with a sphincter muscle. This allows a second possible route of blood flow. Instead of blood flowing through the pulmonary artery to the lungs, the sphincter may be contracted to divert this blood flow through the incomplete ventricular septum into the left ventricle and out through the aorta. This means the blood flows from the capillaries to the heart and back to the capillaries instead of to the lungs. This process is useful to ectothermic (cold-blooded) animals in the regulation of their body temperature.

Birds and mammals show complete separation of the heart into two pumps, for a total of four heart chambers; it is thought[citation needed] that the four-chambered heart of birds evolved independently from that of mammals.

Open circulatory system

The open circulatory system is a system in which a fluid in a cavity called the hemocoel bathes the organs directly with oxygen and nutrients and there is no distinction between blood and interstitial fluid; this combined fluid is called hemolymph or haemolymph.[6] Muscular movements by the animal during locomotion can facilitate hemolymph movement, but diverting flow from one area to another is limited. When the heart relaxes, blood is drawn back toward the heart through open-ended pores (ostia).

Hemolymph fills all of the interior hemocoel of the body and surrounds all cells. Hemolymph is composed of water, inorganic salts (mostly Na+, Cl-, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+), and organic compounds (mostly carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids). The primary oxygen transporter molecule is hemocyanin.

There are free-floating cells, the hemocytes, within the hemolymph. They play a role in the arthropod immune system.

Absence of circulatory system

Circulatory systems are absent in some animals, including flatworms (phylum Platyhelminthes). Their body cavity has no lining or enclosed fluid. Instead a muscular pharynx leads to an extensively branched digestive system that facilitates direct diffusion of nutrients to all cells. The flatworm's dorso-ventrally flattened body shape also restricts the distance of any cell from the digestive system or the exterior of the organism. Oxygen can diffuse from the surrounding water into the cells, and carbon dioxide can diffuse out. Consequently every cell is able to obtain nutrients, water and oxygen without the need of a transport system.

Some animals, such as jellyfish, have more extensive branching from their gastrovascular cavity (which functions as both a place of digestion and a form of circulation), this branching allows for bodily fluids to reach the outer layers, since the digestion begins in the inner layers.

History of discovery

The earliest known writings on the circulatory system are found in the Ebers Papyrus (16th century BCE), an ancient Egyptian medical papyrus containing over 700 prescriptions and remedies, both physical and spiritual. In the papyrus, it acknowledges the connection of the heart to the arteries. The Egyptians thought air came in through the mouth and into the lungs and heart. From the heart, the air travelled to every member through the arteries. Although this concept of the circulatory system is greatly flawed, it represents one of the earliest accounts of scientific thought.

In the 6th century BCE, the knowledge of circulation of vital fluids through the body was known to the Ayurvedic physician Sushruta in ancient India.[7] He also seems to have possessed knowledge of the arteries, described as 'channels' by Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007).[7] The valves of the heart were discovered by a physician of the Hippocratean school around the 4th century BCE. However their function was not properly understood then. Because blood pools in the veins after death, arteries look empty. Ancient anatomists assumed they were filled with air and that they were for transport of air.

The Greek physician, Herophilus, distinguished veins from arteries but thought that the pulse was a property of arteries themselves. Greek anatomist Erasistratus observed that arteries that were cut during life bleed. He ascribed the fact to the phenomenon that air escaping from an artery is replaced with blood that entered by very small vessels between veins and arteries. Thus he apparently postulated capillaries but with reversed flow of blood.[8]

In 2nd century AD Rome, the Greek physician Galen knew that blood vessels carried blood and identified venous (dark red) and arterial (brighter and thinner) blood, each with distinct and separate functions. Growth and energy were derived from venous blood created in the liver from chyle, while arterial blood gave vitality by containing pneuma (air) and originated in the heart. Blood flowed from both creating organs to all parts of the body where it was consumed and there was no return of blood to the heart or liver. The heart did not pump blood around, the heart's motion sucked blood in during diastole and the blood moved by the pulsation of the arteries themselves.

Galen believed that the arterial blood was created by venous blood passing from the left ventricle to the right by passing through 'pores' in the interventricular septum, air passed from the lungs via the pulmonary artery to the left side of the heart. As the arterial blood was created 'sooty' vapors were created and passed to the lungs also via the pulmonary artery to be exhaled.

In 1025, The Canon of Medicine by the Persian physician, Avicenna, "erroneously accepted the Greek notion regarding the existence of a hole in the ventricular septum by which the blood traveled between the ventricles." Despite this, Avicenna "correctly wrote on the cardiac cycles and valvular function", and "had a vision of blood circulation" in his Treatise on Pulse.[9][verification needed] While also refining Galen's erroneous theory of the pulse, Avicenna provided the first correct explanation of pulsation: "Every beat of the pulse comprises two movements and two pauses. Thus, expansion : pause : contraction : pause. [...] The pulse is a movement in the heart and arteries ... which takes the form of alternate expansion and contraction."[10][verification needed]

In 1242, the Arabian physician, Ibn al-Nafis, became the first person to accurately describe the process of pulmonary circulation, for which he is sometimes considered the father of circulatory physiology.[11][failed verification] Ibn al-Nafis stated in his Commentary on Anatomy in Avicenna's Canon:

"...the blood from the right chamber of the heart must arrive at the left chamber but there is no direct pathway between them. The thick septum of the heart is not perforated and does not have visible pores as some people thought or invisible pores as Galen thought. The blood from the right chamber must flow through the vena arteriosa (pulmonary artery) to the lungs, spread through its substances, be mingled there with air, pass through the arteria venosa (pulmonary vein) to reach the left chamber of the heart and there form the vital spirit..."

In addition, Ibn al-Nafis had an insight into what would become a larger theory of the capillary circulation. He stated that "there must be small communications or pores (manafidh in Arabic) between the pulmonary artery and vein," a prediction that preceded the discovery of the capillary system by more than 400 years.[12] Ibn al-Nafis' theory, however, was confined to blood transit in the lungs and did not extend to the entire body.

Michael Servetus was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation, although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. He firstly described it in the "Manuscript of Paris"[13][14] (near 1546), but this work was never published. And later he published this description, but in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. Only three copies of the book survived, the rest were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities. Finally William Harvey, a pupil of Hieronymus Fabricius (who had earlier described the valves of the veins without recognizing their function), performed a sequence of experiments, and published Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus in 1628, which "demonstrated that there had to be a direct connection between the venous and arterial systems throughout the body, and not just the lungs. Most importantly, he argued that the beat of the heart produced a continuous circulation of blood through minute connections at the extremities of the body. This is a conceptual leap that was quite different from Ibn al-Nafis' refinement of the anatomy and bloodflow in the heart and lungs."[15] This work, with its essentially correct exposition, slowly convinced the medical world. However, Harvey was not able to identify the capillary system connecting arteries and veins; these were later discovered by Marcello Malpighi in 1661.

In 1956, André Frédéric Cournand, Werner Forssmann and Dickinson W. Richards were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine "for their discoveries concerning heart catheterization and pathological changes in the circulatory system."[16]

See also

References

- ^ "cardiovascular system" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "circulatory system" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems, by Lauralee Sherwood

- ^ Cardiovascular+System at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Pratt, Rebecca. "Cardiovascular System: Blood". AnatomyOne. Amirsys, Inc. Retrieved 10/12/12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Bailey, Regina. "Circulatory System".

- ^ a b Dwivedi, Girish & Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence. National Informatics Centre (Government of India).

- ^ Anatomy - History of anatomy

- ^ Mohammadali M. Shojaa, R. Shane Tubbsb, Marios Loukasc, Majid Khalilid, Farid Alakbarlie, Aaron A. Cohen-Gadola; Tubbs, RS; Loukas, M; Khalili, M; Alakbarli, F; Cohen-Gadol, AA (29 May 2009), "Vasovagal syncope in the Canon of Avicenna: The first mention of carotid artery hypersensitivity", International Journal of Cardiology, 134 (3), Elsevier: 297–301, doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.02.035, PMID 19332359

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Rachel Hajar (1999), "The Greco-Islamic Pulse", Heart Views 1 (4): 136-140 [138]

- ^ Chairman's Reflections (2004), "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting", Heart Views 5 (2), p. 74-85 [80].

- ^ West, John B. (October 9, 2008), "Ibn al-Nafis, the pulmonary circulation, and the Islamic Golden Age", Journal of Applied Physiology, 105 (6): 1877–80, doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.91171.2008, PMC 2612469, PMID 18845773

- ^ 2011 “The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus”, (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra, 607 pp, 64 of them illustrations, p 215-228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- ^ Michael Servetus Research Study with graphical proof on the Manuscript of Paris and many other manuscripts and new works by Servetus

- ^ Peter E. Pormann and E. Savage Smith, Medieval Islamic medicine Georgetown University, Washington DC, 2007, p. 48.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1956". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

External links

- The Circulatory System Article

- The Circulatory System

- NCP Cardiovascular Medicine A Journal Covering Clinical Cardiovascular Medicine

- Reiber C. L. & McGaw I. J. (2009). "A Review of the "Open" and "Closed" Circulatory Systems: New Terminology for Complex Invertebrate Circulatory Systems in Light of Current Findings". International Journal of Zoology 2009: 8 pages. doi:10.1155/2009/301284.

- Patwardhan K. The history of the discovery of blood circulation: unrecognized contributions of Ayurveda masters. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012 Jun;36(2):77-82. [1]

- Cardiovascular Pedagogical Simulation

- Michael Servetus Research Study on the Manuscript of Paris by Servetus (1546 description of the Pulmonary Circulation)

♥