Lincoln (film): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

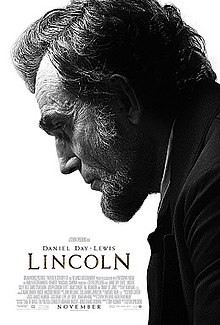

| caption = North American release poster |

| caption = North American release poster |

||

| director = [[Steven Spielberg]] |

| director = [[Steven Spielberg]] |

||

| producer = Steven Spielberg<br />[[Kathleen Kennedy (film producer)|Kathleen Kennedy]] |

| producer = Steven Spielberg<br />[[Kathleen Kennedy (film producer)|Kathleen Kennedy]]<br />Reliance |

||

| screenplay = [[Tony Kushner]] |

| screenplay = [[Tony Kushner]] |

||

| based on = {{based on|''[[Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln]]''|[[Doris Kearns Goodwin]]}} |

| based on = {{based on|''[[Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln]]''|[[Doris Kearns Goodwin]]}} |

||

Revision as of 21:28, 10 January 2013

| Lincoln | |

|---|---|

North American release poster | |

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Tony Kushner |

| Produced by | Steven Spielberg Kathleen Kennedy Reliance |

| Starring | Daniel Day-Lewis Sally Field David Strathairn Joseph Gordon-Levitt James Spader Hal Holbrook Tommy Lee Jones |

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Touchstone Pictures (Domestic) 20th Century Fox (International) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 150 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $65,000,000[3] |

| Box office | $145,040,261[3] |

Lincoln is a 2012 American historical drama film directed and produced by Steven Spielberg, starring Daniel Day-Lewis as United States President Abraham Lincoln and Sally Field as Mary Todd Lincoln.[4] The film is based in part on Doris Kearns Goodwin's biography of Lincoln, Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, and covers the final four months of Lincoln's life, focusing on the President's efforts in January 1865 to have the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution passed by the United States House of Representatives.

Filming began October 17, 2011,[5] and ended on December 19, 2011.[6] Lincoln premiered on October 8, 2012, at the New York Film Festival. The film was released on November 9, 2012, in select cities and widely released on November 16, 2012, in the United States by DreamWorks through Disney’s Touchstone distribution label in the U.S.[7] The film is scheduled for release on January 25, 2013 in the United Kingdom, with distribution in international territories, including the U.K., by 20th Century Fox.[8]

Lincoln received widespread critical acclaim, with major praise directed to Day-Lewis' performance. In December 2012, the film was nominated for seven Golden Globe Awards including Best Picture (Drama), Best Director, and Best Actor (Drama) for Day-Lewis. The film has been nominated for twelve Academy Awards, including Best Actor for Day-Lewis and Best Picture. The film also became a commercial success by grossing over $145 million at the domestic box office.[3]

Plot

Lincoln recounts President Abraham Lincoln's efforts, during January 1865, to pass in the United States House of Representatives the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution that would formally abolish slavery in the country. Expecting the Civil War to end within a month but concerned that his 1863 Emancipation Proclamation may be discarded by the courts once the war has concluded and the 13th Amendment defeated by the returning slave states, Lincoln feels it is imperative to pass the amendment by the end of January, thus removing any possibility that slaves who have already been freed may be re-enslaved. The Radical Republicans fear the amendment will merely be defeated and some wished to delay; the support of the amendment by Republicans in the border states is not yet assured either, since they prioritize the issue of ending the war. Even if all of them are ultimately brought on board, the amendment will still require the support of several Democratic congressmen if it is to pass. With dozens of Democrats having just become lame ducks after losing their re-election campaigns in the fall of 1864, some of Lincoln's advisers believe that he should wait until the new Republican-heavy Congress is seated, presumably giving the amendment an easier road to passage. Lincoln, however, remains adamant about having the amendment in place and the issue of slavery settled before the war is concluded.

Lincoln's hopes for passage of the amendment rely upon the support of the Republican Party founder Francis Preston Blair, the only one whose influence can ensure that all members of the western and border state conservative Republican faction will back the amendment. With Union victory in the Civil War seeming highly likely and greatly anticipated, but not yet a fully accomplished fact, Blair is keen to end the hostilities as soon as possible. Therefore, in return for his support, Blair insists that Lincoln allow him to immediately engage the Confederate government in peace negotiations. This is a complication to Lincoln's amendment efforts since he knows that a significant portion of the support he has garnered for the amendment is from the Radical Republican faction for which a negotiated peace that leaves slavery intact is anathema. If there seems to be a realistic possibility of ending the war even without guaranteeing the end of slavery, needed support for the amendment from the more conservative wing which does not favor abolition will certainly fall away. Unable to proceed without Blair's support, however, Lincoln reluctantly authorizes Blair's mission.

In the meantime, Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward work on the issue of securing the necessary Democratic votes for the amendment. Lincoln suggests that they concentrate on the lame duck Democrats, as they have already lost re-election and thus will feel free to vote as they please, rather than having to worry about how their vote will affect a future re-election campaign. Since those members also will soon be in need of employment and Lincoln will have many federal jobs to fill as he begins his second term, he sees this as a tool he can use to his advantage. Though Lincoln and Seward are unwilling to offer direct monetary bribes to the Democrats, they authorize agents to quietly go about contacting Democratic congressmen with offers of federal jobs in exchange for their voting in favor of the amendment.

With Confederate envoys ready to meet with Lincoln, he instructs them to be kept out of Washington, as the amendment approaches a vote on the House floor. At the moment of truth, Stevens decides to moderate his statements about racial equality to help the amendment's chances of passage. A rumor circulates that there are Confederate representatives in Washington ready to discuss peace, prompting both Democrats and conservative Republicans to advocate postponing the vote on the amendment. Lincoln explicitly denies that such envoys are in or will be in the city — technically a truthful statement, since he had ordered them to be kept away — and the vote proceeds, narrowly passing by a margin of two votes. When Lincoln subsequently meets with the Confederates, he tells them that slavery cannot be restored as the North is united for ratification of the amendment, and that several of the southern states' reconstructed legislatures would also vote to ratify.

After the amendment's passage, the film's narrative shifts forward two months, portraying Lincoln's visit to the battlefield at Petersburg, Virginia, where he exchanges a few words with General Grant. Shortly thereafter, Grant receives General Lee's surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. On the night of April 14, 1865, Lincoln is in a late-night meeting with his cabinet, discussing possible future measures to enfranchise blacks, when he is reminded that Mrs. Lincoln is waiting to take them to their evening at Ford's Theater.

The next morning, after Lincoln is shot, his physician pronounces him dead. The film concludes with a flashback to Lincoln delivering his Second Inaugural Address.

Cast

- Daniel Day-Lewis as President Abraham Lincoln[9]

- Liam Neeson was originally cast as Lincoln in January 2005, having previously worked with Spielberg in Schindler's List.[10] In preparation for the role, Neeson studied Lincoln extensively.[11] However, in July 2010, Neeson left the project, saying that he had grown too old for the part. Neeson was 58 at the time, and Lincoln, during the time period depicted, was 55 and 56.[12] In November 2010, it was announced that Day-Lewis would replace Neeson in the role.[13] Doris Kearns Goodwin described Lincoln in his final months as a leader with "the rare wisdom of a temperament that consistently displayed an uncommon magnanimity to those who opposed him".[14] Producer Kathleen Kennedy described Day-Lewis's performance as "remarkable" after 75% of the filming had been completed, and said, "Every day you get the chills thinking that Lincoln is sitting there right in front of you." Kennedy described Day-Lewis's method acting immersion into the role: "He is very much deeply invested and immersed throughout the day when he's in character, but he's very accessible at the end of the day, once he can step outside of it and not feel that – I mean, he's given huge scenes with massive amounts of dialogue and he needs to stay in character, it's a very, very performance-driven movie."[15]

- Field was first announced to join the cast as early as September 2007, but officially joined the cast in April 2011.[17] Field said, "To have the opportunity to work with Steven Spielberg and Daniel Day-Lewis and to play one of the most complicated and colorful women in American history is simply as good as it gets."[18] Spielberg said, "she has always been my first choice to portray all the fragility and complexity that was Mary Todd Lincoln".[19]

- According to John Hay, "The history of governments affords few instances of an official connection hallowed by a friendship so absolute and sincere as that which existed between these two magnanimous spirits", namely Seward and Lincoln.[21]

- A fervent abolitionist, Stevens feared that Lincoln would "turn his back on emancipation." Stevens "excoriated him on the floor of the House" for meeting with a Confederate peace delegation.[21]

- Hal Holbrook[23] (who won an Emmy portraying Lincoln in a 1976 mini-series) as Francis Preston Blair[24]

- Blair was an influential Republican politician who tried to arrange a peace agreement between the Union and the Confederacy

- Robert Lincoln had recently left his studies at Harvard Law School and was newly named a Union Army captain and personal attendant to General Grant. He returned to the White House on April 14, 1865 to visit his family. His father was assassinated that night.[21]

- James Spader as Republican Party operative William N. Bilbo

- Bilbo had been imprisoned but was freed by Lincoln, and then lobbied for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.[25]

- John Hawkes[23] as Colonel Robert Latham

- Latham founded Lincoln College in 1865

- Jackie Earle Haley as Confederate States Vice President Alexander H. Stephens[26]

- Stephens had served with Lincoln in Congress from 1847 to 1849. He met with Abraham Lincoln on the steamboat River Queen at the unsuccessful Hampton Roads Conference on February 3, 1865

- Lee Pace as Democratic Congressman Fernando Wood: A former Mayor of New York City, Wood became a Copperhead Democratic Congressman sympathetic to the Confederacy

- Gloria Reuben[25] as Elizabeth Keckley

- Keckley was a former slave who was dressmaker and confidant to Mary Todd Lincoln

- Bill Raymond as Schuyler Colfax: Colfax served as the Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1863 to 1869. He was later (1869-1873) Vice President of the United States.

- David Costabile[23] as James Ashley

- Julie White as Elizabeth Blair Lee: Lee was the daughter of Francis Preston Blair, and wrote hundreds of letters documenting events during the Civil War[24]

- S. Epatha Merkerson as Lydia Smith: Smith was Thaddeus Stevens's biracial housekeeper. Stevens was a bachelor and Smith lived with him for many years.[24]

- Elizabeth Marvel as Ms. Jolly[24]

- Stephen Henderson as William Slade[24]

- Adam Driver as Samuel Beckwith[24]

- Lukas Haas as First White Soldier[24]

- Dane DeHaan as Second White Soldier[24]

- Colman Domingo as Private Harold Green[24]

- Michael Stuhlbarg as George Yeaman[24]

- Stephen Spinella as Asa Vintner Litton[24]

- Bruce McGill as Secretary of War Edwin Stanton[27]

- Stanton took charge of the investigation of the assassination plot[21]

- Schell was a politician who later represented New York in the United States House of Representatives.

- Hay was assistant and secretary to Abraham Lincoln, and later Secretary of State under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

- Commanded the Union Army from March 1864 and directed the strategy that led to Union Victory.

- Peter McRobbie as Ohio Democrat, U.S. Representative George H. Pendleton

- Gulliver McGrath as Tad Lincoln[29]

- Tad was 12 years old, and toured Richmond, Virginia, with his father.

- Jeremy Strong[23] as John George Nicolay[24]

- Nicolay was secretary to Abraham Lincoln

- Boris McGiver[23] as Alexander Coffroth

- Walton Goggins as Democratic Congressman Wells A. Hutchins[30]

- Hutchins was one of only 16 Democrats who broke with his party to cast decisive votes in favor of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished slavery

- David Warshofsky[23] as William Hutton

- David Oyelowo as Ira Clark[31]

- Byron Jennings[23] as Montgomery Blair[24]

- Blair was the son of Francis Preston Blair, was the former Postmaster-General, and was a political opponent of the Radical Republicans

- Richard Topol as James Speed[24]

- Speed was United States Attorney General and brother of Joshua Speed, Lincoln's oldest personal friend

- Usher was the Secretary of the Interior in Lincoln's cabinet

- Wayne Duvall as Radical Republican Senator Benjamin "Bluff Ben" Wade

- Gregory Itzin as John Archibald Campbell[24]

- Campbell was a former Supreme Court Justice who had resigned at the start of war and then served as Assistant Secretary of War in the Confederate government. He was also a member of the Confederate delegation that met with Lincoln at the Hampton Roads Conference

Production

While consulting on a Steven Spielberg project in 1999, Goodwin told Spielberg she was planning to write Team of Rivals, and Spielberg immediately told her he wanted the film rights.[32] DreamWorks finalized the deal in 2001,[10] and by the end of the year, John Logan signed on to write the script.[33] His draft focused on Lincoln's friendship with Frederick Douglass.[34] Playwright Paul Webb was hired to rewrite and filming was set to begin in January 2006,[10] but Spielberg delayed it out of dissatisfaction with the script.[35] Neeson said Webb's draft covered the entirety of Lincoln's term as President.[36]

Tony Kushner replaced Webb. Kushner considered Lincoln "the greatest democratic leader in the world" and found the writing assignment daunting because "I have no idea [what made him great]; I don't understand what he did anymore than I understand how William Shakespeare wrote Hamlet or Mozart wrote Così fan tutte." He delivered his first draft late and felt the enormous amount written about Lincoln did not help either. Kushner said Lincoln's abolitionist ideals made him appealing to a Jewish writer, and although he felt Lincoln was Christian, he noted the president rarely quoted the New Testament and that his "thinking and his ethical deliberation seem very talmudic".[37] By late 2008, Kushner joked he was on his "967,000th book about Abraham Lincoln".[38] Kushner's initial 500-page draft focused on four months in the life of Lincoln, and by February 2009 he had rewritten it to focus on two months in Lincoln's life when he was preoccupied with adopting the Thirteenth Amendment.[36]

While promoting Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull in May 2008, Spielberg announced his intention to start filming in early 2009,[39] for release in November, ten months after the 200th anniversary of Lincoln's birth.[32] In January 2009, Taunton and Dighton, Massachusetts were being scouted as potential locations.[40] Spielberg arranged a $50 million budget for the film, to please Paramount Pictures CEO Brad Grey, who had previously delayed the project over concerns it was too similar to Spielberg's commercially unsuccessful Amistad (1997). Spielberg had wanted Touchstone Pictures–which agreed to distribute all his films from 2010–to distribute the film, but he was unable to afford paying off Paramount, which DreamWorks had developed the film with.[41]

Filming took place in Petersburg, Virginia. According to location manager Colleen Gibbons, "one thing that attracted the filmmakers to the city was the 180-degree vista of historic structures" which is "very rare".[42] Lincoln toured Petersburg on April 3, 1865, the day after it fell to the Union Army. Scenes have also been filmed in Fredericksburg, Virginia and at the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond, which served as the Capitol of the Confederacy during the Civil War.[26][43] Abraham Lincoln visited the building on April 4, 1865, after Richmond fell to the Union Army.

On September 4, 2012, DreamWorks and Google Play announced on the film's Facebook page that they would release the trailer for the film during a Google+ hangout with Steven Spielberg and Joseph Gordon-Levitt on September 13, 2012 at 7pm EDT/4pm PDT.[44] Then, on September 10, 2012, a teaser for the trailer was released.[45]

Music

The soundtrack to Lincoln was released on November 6, 2012 in the United States and was recorded by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Chicago Symphony Chorus.[46][47]

All music is composed by John Williams

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The People’s House" | 3:43 |

| 2. | "The Purpose of the Amendment" | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Getting Out the Vote" | 2:49 |

| 4. | "The American Process" | 3:57 |

| 5. | "The Blue and Grey" | 3:00 |

| 6. | "With Malice Toward None" | 1:51 |

| 7. | "Call to Muster and Battle Cry of Freedom" | 2:17 |

| 8. | "The Southern Delegation and the Dream" | 4:43 |

| 9. | "Father and Son" | 1:42 |

| 10. | "The Race to the House" | 2:42 |

| 11. | "Equality Under the Law" | 3:12 |

| 12. | "Freedom's Call" | 6:08 |

| 13. | "Elegy" | 2:35 |

| 14. | "Remembering Willie" | 1:51 |

| 15. | "Appomattox, April 9, 1865" | 2:38 |

| 16. | "The Peterson House and Finale" | 11:00 |

| 17. | "With Malice Toward None (Piano Solo)" | 1:31 |

| Total length: | 58:46 | |

Reception

Box office

As of January 9, 2013, the film has made $145,040,261 domestically from 2,293 theaters, well exceeding its budget. The film opened limited in 11 theaters with $944,308 and an average of $85,846 per theater. It opened at the #15 rank, becoming the highest opening of a film with such a limited release. The film opened wide in 1,175 theaters with $21,049,406 and an average of $11,859 per theater.[3]

Critical response

Lincoln received widespread critical acclaim. The film currently holds a 91% "Certified Fresh" approval rating (95% among "Top Critics") on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 8.1/10. The site's critical consensus is "Daniel Day-Lewis characteristically delivers in this witty, dignified portrait that immerses the audience in its world and entertains even as it informs."[48] On Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 based on reviews from critics, the film has a score of 86 (citing "universal acclaim") based on 41 reviews, making it Spielberg's highest rated film on the site since Saving Private Ryan.[49]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 4 out of 4 stars and said, "The hallmark of the man, performed so powerfully by Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln, is calm self-confidence, patience and a willingness to play politics in a realistic way." Ebert went on to name it as one of the best films of the year.[50] Glenn Kenny of MSN Movies gave it 5 out of 5 stars stating, "It's the most remarkable movie Steven Spielberg has made in quite a spell, and one of the things that makes it remarkable is how it fulfills those expectations by simultaneously ignoring and transcending them."[51]

It has been praised by Charlie McCollum of the San Jose Mercury News as one "of the finest historical dramas ever committed to film." Despite mostly positive reviews, Rex Reed of the New York Observer stated, "In all, there's too much material, too little revelation and almost nothing of Spielberg's reliable cinematic flair." However, the reviews have been unanimous in their praise of Daniel Day-Lewis's performance as Abraham Lincoln. A. O. Scott from The New York Times stated the movie "is finally a movie about how difficult and costly it has been for the United States to recognize the full and equal humanity of black people" and concluded that the movie was "a rough and noble democratic masterpiece".[52]

Scott also stated that Lincoln's concern about his wife's emotional instability and "the strains of a wartime presidency... produce a portrait that is intimate but also decorous, drawn with extraordinary sensitivity and insight and focused, above all, on Lincoln's character as a politician. This is, in other words, less a biopic than a political thriller, a civics lesson that is energetically staged and alive with moral energy."[52]

Academic historians have been more ambivalent in their reaction than movie critics. Eric Foner (Columbia University), a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the period, claims in a letter to the New York Times that the movie “grossly exaggerates” its main points about the choices at stake in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment (November 26, 2012).[53] Kate Masur (Northwestern University) accuses the film of oversimplifying the role of blacks in abolition and dismisses the effort as “an opportunity squandered” in an op-ed for the New York Times (November 12, 2012).[54] Harold Holzer, co-chair of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation and author of more than 40 books, served as a consultant to the film and praises it but also observes that there is “no shortage of small historical bloopers in the movie” in a piece for The Daily Beast (November 22, 2012).[55] Allen Guelzo (Gettysburg College), also writing for The Daily Beast has some plot criticism, but disagrees with Holzer, arguing that, “The pains that have been taken in the name of historical authenticity in this movie are worth hailing just on their own terms” (November 27, 2012).[56] David Stewart, independent historical author, writing for History News Network, describes Spielberg’s work as “reasonably solid history” and tells readers of HNN, “go see it with a clear conscience” (November 20, 2012).[57] Lincoln Biographer Ronald White also admired the film, though he noted a few mistakes and pointed out in an interview with NPR, “Is every word true? No.” (November 23, 2012).[58] Historian Joshua M. Zeitz, writing in The Atlantic, noted some minor mistakes, but concluded "Lincoln is not a perfect film, but it is an important film."[59] However American Civil War historian Ed Goodger described the content of the film as having "great inaccuracies simply for the sake of drama", saying that for much of the civil war Lincoln blocked emancipation due to the risk of an escalation in the war.[citation needed]

Home media

Lincoln will be released on Blu-ray, DVD, and digital download on February 26, 2013 from Touchstone Home Entertainment. The release will be produced in two different physical packages: a 2-disc combo pack (Blu-ray and DVD); and a 1-disc DVD.

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients and nominees | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFI Awards 2012[60] | January 11, 2013 | Movies of the Year | Won | |

| 85th Academy Awards | February 24, 2013 | Best Picture | Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy | Pending |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Pending | ||

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Pending | ||

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Tommy Lee Jones | Pending | ||

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Sally Field | Pending | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Pending | ||

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Pending | ||

| Best Sound Mixing | Andy Nelson, Gary Rydstrom & Ronald Judkins | Pending | ||

| Best Produciton Design | Rick Carter & Jim Erickson | Pending | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Pending | ||

| Best Costume Design | Joanna Johnston | Pending | ||

| Best Film Editing | Michael Kahn | Pending | ||

| Alliance of Women in Film Journalists Association | January 7, 2013 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director (Female or Male) | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay, Adapted | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Sally Field | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won | ||

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Tommy Lee Jones | Nominated | ||

| Best Ensemble Cast | Nominated | |||

| 33rd Boston Society of Film Critics Award[61] | December 9, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Won | ||

| Best Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Won | ||

| 66th British Academy Film Awards[62] | February 10, 2013 | Best Film | Pending | |

| Best Actor in a Leading Role | Daniel Day-Lewis | Pending | ||

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Tommy Lee Jones | Pending | ||

| Best Actress in a Supporting Role | Sally Field | Pending | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Pending | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kaminski | Pending | ||

| Best Original Music | John Williams | Pending | ||

| Best Production Design | Rick Carter, Jim Erickson | Pending | ||

| Best Costume Design | Joanna Johnston | Pending | ||

| Best Makeup and Hair | Leo Corey Castellano, Mia Kovero | Pending | ||

| 18th Critics' Choice Awards[63] | January 11, 2013 | Best Picture | Pending | |

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Pending | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Pending | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Pending | ||

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Pending | ||

| Best Acting Ensemble | Pending | |||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Pending | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Pending | ||

| Best Art Direction | Rick Carter, Jim Erickson | Pending | ||

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn | Pending | ||

| Best Costume Design | Joanna Johnston | Pending | ||

| Best Makeup | Leo Corey Castellano, Mia Kovero | Pending | ||

| Best Score | John Williams | Pending | ||

| Chicago Film Critics Association[64] | December 17, 2012 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Won | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction | Nominated | |||

| 6th Detroit Film Critics Society Awards[65] | December 14, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Nominated | ||

| Best Ensemble | Won | |||

| Best Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| 65th Director's Guild of America Awards [66] | February 2, 2012 | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Feature Film | Steven Spielberg | Pending |

| 70th Golden Globe Awards [67] | January 13, 2013 | Best Motion Picture - Drama | Pending | |

| Best Actor - Motion Picture Drama | Daniel Day-Lewis | Pending | ||

| Best Supporting Actor - Motion Picture | Tommy Lee Jones | Pending | ||

| Best Supporting Actress - Motion Picture | Sally Field | Pending | ||

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Pending | ||

| Best Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Pending | ||

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Pending | ||

| 3rd International Online Film Critics' Poll[68][69] | December 20, 2012 | Best Film - Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Top Ten Films | Won | |||

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor in a Leading Role | Daniel Day-Lewis | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Won | ||

| Best Production Design | Rick Carter | Nominated | ||

| Best Editing | Michael Kahn | Nominated | ||

| Las Vegas Film Critics Society[70] | December 13, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Won | ||

| National Board of Review of Motion Pictures[71] | December 5, 2012 | Top 10 Films | Won | |

| 78th New York Film Critics Circle Awards[72] | December 3, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Won | ||

| Best Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Won | ||

| 12th New York Film Critics Online Awards[73] | December 9, 2012 | Top 10 Films of 2012 | Won | |

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Won | ||

| North Texas Film Critics Association | January 7, 2013 | Best Picture | Won | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Won | ||

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Won | ||

| 24th Producers Guild of America Awards[74] | January 26, 2013 | Best Theatrical Motion Picture | Kathleen Kennedy and Steven Spielberg | Pending |

| 17th San Diego Film Critics Society Awards[75] | December 11, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| 17th Satellite Awards[76] | December 16, 2012 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Nominated | ||

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Tommy Lee Jones | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| Best Original Score | John Williams | Nominated | ||

| Best Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński | Nominated | ||

| Best Art Direction & Production Design | Curt Beech, Rick Carter, David Crank, Leslie McDonald | Won | ||

| 19th Screen Actors Guild Awards[77] | January 27, 2013 | Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture | Pending | |

| Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Leading Role | Daniel Day-Lewis | Pending | ||

| Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role | Tommy Lee Jones | Pending | ||

| Outstanding Performance by a Female Actor in a Supporting Role | Sally Field | Pending | ||

| Washington D.C. Area Film Critics Association Awards 2012 | December 10, 2012 | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won | ||

| Best Supporting Actor | Tommy Lee Jones | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actress | Sally Field | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Steven Spielberg | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Nominated | ||

| Best Acting Ensemble | Nominated | |||

| Best Art Direction | Rick Carter and Jim Erickson | Nominated | ||

| Best Score | John Williams | Nominated | ||

| Women Film Critics Circle | December 22, 2012 | Best Actor | Daniel Day-Lewis | Won |

| Best Male Images | Won | |||

| Writers Guild of America Award [78] | February 17, 2013 | Best Adapted Screenplay | Tony Kushner | Pending |

See also

References

- ^ The Deadline Team (July 18, 2012). "Disney Dates Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' Into Awards-Season Fray".

- ^ "LINCOLN (12A)". British Board of Film Classification. November 28, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Lincoln (2012)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (April 13, 2011). "Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' gets its Mary Todd: Sally Field". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (October 12, 2011). "Participant Media Boarding Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' (Exclusive)". Hollywood Reporter. Los Angeles. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "Filmmakers really liked Petersburg". The Progress-Index. Petersburg, Virginia. December 29, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2012.

- ^ Fischer, Russ (November 19, 2010). "Daniel Day-Lewis to Star in Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln'". /Film.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (January 23, 2012). "Fox Partnering with DreamWorks on Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ^ Fischer, Russ (November 19, 2010). "Daniel Day-Lewis to Star in Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln'". /Film. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c Michael Fleming (January 11, 2005). "Lincoln logs in at DreamWorks: Spielberg, Neeson eye Abe pic". Variety. Retrieved January 24, 2007.

- ^ Max Evry (January 24, 2007). "Liam Neeson Talks Lincoln". Comingsoon.net. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ^ Simon Reynolds (July 30, 2010). "Neeson quits Spielberg's Lincoln biopic". Digital Spy.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (November 19, 2010). "Daniel Day-Lewis set for Steven Spielberg's Lincoln film". The Guardian. Retrieved November 19, 2010.

- ^ "Day-Lewis 'remarkable' as Lincoln". Irish Independent. Dublin. December 9, 2011. Retrieved December 11, 2011.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (April 13, 2011). "Sally Field Set to Play Mary Todd Lincoln in Steven Spielberg's LINCOLN". Collider.com. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ Carly Mayberry (September 25, 2007). "Field is Spielberg's new first lady". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 26, 2007. [dead link]

- ^ "Sally Field Set to Play Mary Todd Lincoln in Steven Spielberg's LINCOLN". Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ Roberts, Roxanne (April 13, 2011). "Sally Field to play Mary Todd Lincoln; actress prepped for role with visit to Ford's Theatre". Washington Post. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Joshua L. Weinstein (June 27, 2011). "David Strathairn Joins DreamWorks' 'Lincoln'". TheWrap.com. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2006). Team of Rivals. Simon & Schuster. pp. 686–754. ISBN 978-0-7432-7075-5.

- ^ a b Goetz, Barrett (May 5, 2011). "Tommy Lee Jones & Joseph Gordon-Levitt Join Spielberg's 'Lincoln'". TheMovieMash.com. Retrieved June 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Schaefer, Sandy. "Spielberg's 'Lincoln' Casts Every Other Good Actor Under The Sun". Screen Rant. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Lipton, Brian Scott (November 28, 2011). "Steven Spielberg's Lincoln Announces Additional Casting". TheaterMania.com. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Spielberg's 'Lincoln' Casts Every Other Good Actor Under The Sun". Retrieved November 24, 2011. Cite error: The named reference "http://screenrant.com/steven-spielberg-lincoln-cast-sandy-114090/" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Vincent, Mal (October 14, 2011). "Spielberg's 'Lincoln' takes Richmond". The Virginian-Pilot. Norfolk, Virginia. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ Jeanne Jakle (July 30, 2011). "Jeanne Jakle: McGill's profile going higher and higher". mysanantonio.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- ^ "Tim Blake Nelson tapped for Spielberg's 'Lincoln' film in 2012". Retrieved November 25, 2011.

- ^ Labrecque, Jeff (November 28, 2011). "'Lincoln': Meet the Cast". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "Walton Goggins Joins Cast Of 'Lincoln'". Deadline Hollywood. July 11, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "David Oyelowo Joins Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln'". Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ a b Ruben V. Nepales (May 18, 2008). "Spielberg may co-direct next with Peter Jackson". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "Logan Scripting Spielberg's Lincoln". IGN. December 7, 2001. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ "Lincoln Update". IGN. January 23, 2003. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Ron Grover (April 17, 2006). "The Director's Cut". BusinessWeek. Retrieved August 10, 2007.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Wells (February 2, 2009). "Spielberg's Lincoln in December?". Hollywood Elsewhere. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Naomi Pffefferman (October 25, 2007). "Kushner's (old) testament to Lincoln". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved November 22, 2008.

- ^ Karen Bovard (November 20, 2008). "Lincoln Logs". Hartford Advocate. Retrieved November 23, 2008.

- ^ Sheigh Crabtree (May 10, 2008). "Steven Spielberg: He wants to shoot 'Abraham Lincoln' in 2009". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ^ Charles Winokoor (February 7, 2009). "Film crews may be back in Silver City". Taunton Daily Gazette. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Kim Masters (February 17, 2009). "Spielberg's Lincoln Troubles". Slate. Retrieved February 18, 2009.

- ^ Wiggins, F.M. (November 17, 2011). "Lincoln film to come to Petersburg next month". Progress-Index. Petersburg, Virginia. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Kumar, Anita (November 8, 2011). "Virginia Politics: Lights, camera, action. Spielberg's Lincoln movie films at Capitol". Washington Post. Washington, DC. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Lincoln Google Hangout and Trailer Premiere Announced for September 13th". ComingSoon.net. Los Angeles, CA. September 4, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- ^ "Take a Sneak Peek at Steven Spielberg's Lincoln Trailer". ComingSoon.net. Los Angeles, CA. September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ "John Williams' Tracklist For Score To Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' Is Suitably Important & Historical". Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ "John Williams' Lincoln Score Gently Spoils A Few Key Scenes". Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Lincoln". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 03, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Metacritic". Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ "Roger Ebert's review of Lincoln". Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ "Review by Glenn Kenny (MSN Movies)". Retrieved January 03, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b Scott, A. O. (November 8, 2012). "A President Engaged in a Great Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ "Lincoln's Use of Politics for Noble Ends". NYTimes.com. November 26, 2012. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Kate Masur (November 12, 2012). "In Spielberg's 'Lincoln,' Passive Black Characters". NYTimes.com. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Harold Holzer (November 22, 2012). "What's True and False in "Lincoln" Movie". The Daily Beast. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Frum, David (November 27, 2012). "A Civil War Professor Reviews 'Lincoln'". The Daily Beast. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ Author: David O. Stewart. "How True is "Lincoln"? | History News Network". Hnn.us. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Updated: Nov 23, 2012 04:49 PM EST (November 23, 2012). "Fact-Checking Steven Spielberg's 'Lincoln' Movie with Biographer Ronald C. White : Books : Books & Review". Booksnreview.com. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fact-Checking 'Lincoln': Lincoln's Mostly Realistic; His Advisers Aren't - Joshua Zeitz". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 4, 2012.

- ^ "AFI Awards 2012". American Film Institute. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Winners". Boston Society of Film Critics. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "'Lincoln' dominates BAFTA nominations, earning 10". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ "'LINCOLN' LEADS THE 18TH ANNUAL CRITICS' CHOICE MOVIE AWARDS NOMINATIONS WITH A RECORD 13 NOMS". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Chicago Film Critics Awards". Chicago Film Critics Association. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "The 2012 Detroit Film Critics Society Awards". Detroit Film Critics Society. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ "Affleck, Spielberg, Bigelow among Director's Guild film nominees". DGA. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- ^ "2013 Golden Globe Nominations". HFPA. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/news/ni41861385/

- ^ http://www.flickeringmyth.com/2012/12/international-online-film-critics-poll_20.html

- ^ "LVFCS Sierra Award Winners". LVFCS. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ "2013 National Board Of Review Awards". MovieCityNews.com. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ NYFCC. "2012 Awards". NYFCC. NYFCC. Retrieved December 3, 2012.

- ^ "New York Film Critics Online Hail "Zero Dark Thirty"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "PGA Motion Picture Nominees Announced". PGA. Retrieved January 03, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "San Diego Film Critics Select Top Films for 2012". SDFCS. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "17th Satellite Awards Nominations". International Press Academy. Retrieved December 5, 2012.

- ^ "Nominations Announced for the 19th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". December 11, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "2013 Writers Guild Awards Screen Nominations Announced". WGA. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

External links

- Official website

- Lincoln at IMDb

- Lincoln at Rotten Tomatoes

- Lincoln at Metacritic

- Lincoln on Facebook

- Lincoln at Box Office Mojo

- Lincoln: Meet the Cast at the Entertainment Weekly

- Lincoln's Last Days: Short Film and Original Historical Manuscripts Shapell Manuscript Foundation

- 2012 films

- 2010s drama films

- English-language films

- American drama films

- American biographical films

- American Civil War films

- American war films

- 2010s war films

- Abraham Lincoln in art

- Biographical films about Abraham Lincoln

- Films set in the 1860s

- Films about American slavery

- Films about politicians

- Films based on non-fiction books

- Films shot in Virginia

- Films produced by Steven Spielberg

- Films directed by Steven Spielberg

- Touchstone Pictures films

- DreamWorks films

- 20th Century Fox films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- Films distributed by Disney