Christianity: Difference between revisions

Homestarmy (talk | contribs) Planemo, those references aren't for "religion", their for "monotheistic", which is what Christianity is. Also, the other thing you changed is OR by your edit, while the previous version isn't. |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

==Groups within Christianity== |

==Groups within Christianity== |

||

[[Image:Ivanov pagans.jpg|thumb|250px|Christians and pagans]] |

|||

There is a diversity of [[doctrine]]s and practices among various groups calling themselves Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under [[Christian denomination|denomination]]s, though for various theological reasons many groups reject this classification system.<ref>S. E. Ahlstrom characterized denominationalism in America as “a virtual ecclesiology” that “first of all repudiates the insistences of the Roman Catholic church, the churches of the ‘magisterial’ Reformation, and of most sects that they alone are the true Church." Ahlstrom p. 381. For specific citations, on the Roman Catholic Church see the ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' §816; other examples: Donald Nash, [http://www.crownhillchurch.com/Why_the_Churches_of_Christ_Are_Not_A_Denomination.pdf#search=%22church%20of%20christ%20not%20a%20denomination%22 Why the Churches of Christ are not a Denomination]; Wendell Winkler, [http://www.thebible.net/introchurch/ch4.html Christ's Church is not a Denomination]; and David E. Pratt, [http://www.biblestudylessons.com/cgi-bin/gospel_way/denominations.php What does God think about many Christian denominations?]</ref> At other times these groups are described in terms of varying [[tradition]]s, representing core historical similarities and differences. Christianity may be broadly represented as being [[Schism (religion)|divided]] into three main groupings:<ref>Encyclopedia Britannica, [http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9360716 Christianity]</ref> |

There is a diversity of [[doctrine]]s and practices among various groups calling themselves Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under [[Christian denomination|denomination]]s, though for various theological reasons many groups reject this classification system.<ref>S. E. Ahlstrom characterized denominationalism in America as “a virtual ecclesiology” that “first of all repudiates the insistences of the Roman Catholic church, the churches of the ‘magisterial’ Reformation, and of most sects that they alone are the true Church." Ahlstrom p. 381. For specific citations, on the Roman Catholic Church see the ''Catechism of the Catholic Church'' §816; other examples: Donald Nash, [http://www.crownhillchurch.com/Why_the_Churches_of_Christ_Are_Not_A_Denomination.pdf#search=%22church%20of%20christ%20not%20a%20denomination%22 Why the Churches of Christ are not a Denomination]; Wendell Winkler, [http://www.thebible.net/introchurch/ch4.html Christ's Church is not a Denomination]; and David E. Pratt, [http://www.biblestudylessons.com/cgi-bin/gospel_way/denominations.php What does God think about many Christian denominations?]</ref> At other times these groups are described in terms of varying [[tradition]]s, representing core historical similarities and differences. Christianity may be broadly represented as being [[Schism (religion)|divided]] into three main groupings:<ref>Encyclopedia Britannica, [http://www.britannica.com/ebc/article-9360716 Christianity]</ref> |

||

* [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholicism]]: The [[Roman Catholic Church]], the largest single body, includes [[Latin Rite]] and several [[Eastern Catholic]] communities and totals more than 1 billion baptized members.<ref name="Adherents" /> |

* [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholicism]]: The [[Roman Catholic Church]], the largest single body, includes [[Latin Rite]] and several [[Eastern Catholic]] communities and totals more than 1 billion baptized members.<ref name="Adherents" /> |

||

Revision as of 20:51, 25 December 2006

Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christianity is a monotheistic[1] religion centered on Jesus of Nazareth and his life, death, resurrection, and teachings as presented in the New Testament.[2] Christians believe Jesus is the Son of God and the Messiah prophesied in the Old Testament. With an estimated 2.1 billion adherents in 2001, Christianity is the world's largest religion.[3] It is the predominant religion in the Americas, Europe, Philippine Islands, Oceania, and large parts of Africa (see Christianity by country). It is also growing rapidly in Asia, particularly in China and South Korea, and in Northern Africa.[4]

Christianity began in the 1st century AD as a Jewish sect,[5] and shares many religious texts with Judaism, specifically the Hebrew Bible, known to Christians as the Old Testament (see Judeo-Christian). Like Judaism and Islam, Christianity is classified as an Abrahamic religion because of the centrality and pre-cedence of Abraham in their shared traditions; though Jesus himself stated that he had pre-existed Abraham (John 8:58), and Christianity places Jesus as God incarnate (not Abraham) as central to the faith. The name "Christian" (Greek [Χριστιανός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Strong's G5546) was first applied to the disciples in Antioch, as recorded in 11:26 Acts 11:26.[6] The earliest recorded use of the term Christianity (Greek [Χριστιανισμός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is by Ignatius of Antioch.[7]

Groups within Christianity

There is a diversity of doctrines and practices among various groups calling themselves Christian. These groups are sometimes classified under denominations, though for various theological reasons many groups reject this classification system.[8] At other times these groups are described in terms of varying traditions, representing core historical similarities and differences. Christianity may be broadly represented as being divided into three main groupings:[9]

- Roman Catholicism: The Roman Catholic Church, the largest single body, includes Latin Rite and several Eastern Catholic communities and totals more than 1 billion baptized members.[3]

- Eastern Christianity: Eastern Orthodox Churches, Oriental Orthodox Churches, the 100,000 member Assyrian Church of the East,[10] and others with a combined membership of more than 300 million baptized members.[3]

- Protestantism: Numerous groups such as Anglicans, Lutherans, Reformed/Presbyterians, Congregational/United Church of Christ, Evangelical, Charismatic, Baptists, Methodists, Nazarenes, Anabaptists, Seventh-day Adventists and Pentecostals. The oldest of these separated from the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century Protestant Reformation, followed in many cases by further divisions. Estimates of the total number of Protestants are very uncertain, partly because of the difficulty in determining which denominations should be placed in this category, but it seems to be unquestionable that Protestantism is the second major branch of Christianity (after Roman Catholicism) in number of followers.[3]

The above groupings are not without exceptions. Some Protestants identify themselves simply as Christian, or born-again Christian; they typically distance themselves from the confessionalism of many Protestant communities that emerged during the Reformation[11] by calling themselves "non-denominational" — often founded by individual pastors, they have little affiliation with historic denominations (Methodists, Baptists, Anglicans, etc.). Others, particularly some Anglicans, eschew the term Protestant and thus insist on being thought of as Catholic, adopting the name "Anglo-Catholic".[12] Finally, various small communities, such as the Old Catholic and Independent Catholic Churches, are similar in name to the Roman Catholic Church, but are not in communion with the See of Rome.

Restorationists, who are historically connected to the Protestant Reformation,[13] do not describe themselves as "reforming" a Christian Church continuously existing from the time of Jesus, but as restoring the Church that was historically lost at some point. Restorationists include Churches of Christ with 2.6 million members, Disciples of Christ with 800,000 members,[14] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 12 million members,[3] and Jehovah’s Witnesses with 6.6 million members.[15] Though Restorationists have some basic similarities, their doctrine and practices vary and can be significantly different.

Since certain of these groups deviate from the tenets which most groups hold as basic to Christianity, they are considered heretical or even non-Christian by many mainstream Christian groups; this is particularly true for non-trinitarians.

Ecumenism

Most churches have long expressed ideals of being reconciled with different believers, and in the 20th Century Christian ecumenism advanced significantly in two ways. One way was greater cooperation between groups particularly in outreach. Examples include the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of Protestants in 1910, the Justice, Peace and Creation Commission of the World Council of Churches founded in 1948 by Protestant and Orthodox churches, and similar national councils like the National Council of Churches in Australia which also includes Roman Catholics.

The other way was organic union with new united churches being formed by denominational mergers. Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches united in 1925 to form the United Church of Canada and in 1977 to form the Uniting Church in Australia. The Church of South India was formed in 1947 by the union of Anglican, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, and Reformed churches.

Steps towards union on a global level have also been taken in 1965 by the Catholic and Orthodox churches mutually revoking the excommunications that marked their Great Schism in 1054; the Anglican Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) working towards full communion between those churches since 1970; and the Lutheran and Catholic churches signing The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification in 1999 to resolve conflicts at the root of the Protestant Reformation. In 2006 the Methodist church also adopted the declaration.

Beliefs

Although Christianity has always had a significant diversity of belief, mainstream Christianity considers certain core doctrines essential. Those accepting them often consider followers of Jesus who disagree with these doctrines to be heterodox, heretical, or outside Christianity altogether.

Jesus Christ

Christians identify Jesus as the Messiah. The title Messiah comes from the Hebrew word מָשִׁיחַ (māšiáħ) meaning "the anointed one". The Greek translation [Χριστός] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Christos) is the source of the English word Christ. Christians believe that, as Messiah, Jesus was anointed as ruler and savior of both the Jewish people specifically and of humanity in general, and hold that Jesus's coming was the fulfilment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of Messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. [16]

Most Christians believe that Jesus is "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human in all respects, including the aspect of mortality, suffered the pains and temptations of mortal man, yet he did not sin. As fully God, he defeated death and rose to life again with the resurrection. (See Death and Resurrection of Jesus).

According to Christian Scripture, while still a virgin, Mary conceived Jesus not by sexual intercourse, but by the power of the Holy Spirit. (See Nativity of Jesus)

Little of Jesus's childhood is recorded in the Gospels compared to his adulthood, especially the week before his death. The Biblical accounts begin with his baptism, and go on to recount miracles (e.g. turning water into wine at a marriage at Cana, exorcisms, healings, &c.), quote his teachings (e.g. the Sermon on the Mount and parables) and narrate his deeds (e.g. calling the Twelve Apostles and sharing hospitality with outcasts and the poor).

|

Death and Resurrection

Many Christians consider the death of Jesus, followed by his resurrection, the most important event in history.[17] According to the Gospels, Jesus and his followers went to Jerusalem for the Passover and, in triumphal entry, he was eagerly greeted by a crowd. Jesus also cleansed the Temple courts from traders and money changers[18] and enjoyed a meal — the Last Supper, possibly the Passover Seder — with his disciples before going to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane. There he was arrested by Roman soldiers on orders from the Sanhedrin and the high priest Caiaphas. The arrest took place clandestinely at night to avoid a riot, because Jesus was popular with many of the people in Jerusalem. Judas Iscariot, one of Jesus' apostles, betrayed Him by identifying his location to the authorities for money.

Following the arrest, Jesus was tried by the Sanhedrin, which found him guilty of blasphemy and wished to execute him, though it lacked the legal authority. Thus Jesus was sent to Pontius Pilate, who in turn sent him to Herod Antipas. Herod, though initially excited at meeting Jesus, ended up mocking him and sending him back to Pilate. Pilate, in accord with a Passover custom where the Roman governor freed one prisoner, offered the crowd a choice between Jesus and an insurrectionist named Barabbas. The crowd chose to have Barabbas freed and Jesus crucified. Pilate washed his hands, to display that he claimed innocence of the injustice of the decision. Pilate then ordered Jesus to be crucified with a charge, the titulus crucis, placed atop the cross which read "Jesus the Nazarene, the King of the Jews". Jesus died by late afternoon and was buried by Joseph of Arimathea.

Jesus was raised from the dead on the third day since his crucifixion, then later appeared first to Mary Magdalene, to his assembled disciples on the evening after his resurrection, and to various people in several places over the next forty days. During one of these visits, Jesus' disciple Thomas initially doubted the resurrection, but after being invited to place his finger in Jesus' pierced side he said to him: "My Lord and my God!" Before his Ascension Jesus instructed his Apostles to "...go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit...",[19] a command known as the Great Commission.

Salvation

Most Christians believe that salvation from "sin and death" is available through faith in Jesus as saviour because of his atoning sacrifice on the cross which paid for sins. Reception of salvation is related to justification and usually understood as the activity of unmerited Divine grace.[20]

The operation and effects of grace are understood differently by different traditions. Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy teach the necessity of the free will to cooperate with grace.[21] Reformed theology goes furthest in emphasizing dependence on grace by teaching the total depravity of mankind and the irresistibility of grace.[22] (See Five points of Calvinism)

The Trinity

Most Christians believe that God is one eternal being who exists as three distinct, eternal, and indivisible persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ the eternal Word), and the Holy Spirit.

Christianity continued from Judaism a belief in the existence of a single omnipotent God who created and sustains the universe. Against this background belief in the divinity of Christ and the Holy Spirit became expressed as the doctrine of the Holy Trinity,[23] which considers the three persons of God (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) share a single Divine substance. This substance is not considered divided, in the sense that each person has a third of the substance; rather, each person is considered to have the whole substance. The distinction lies in their origins or relations, the Father being unbegotten, the Son begotten of the Father, and the Holy Spirit proceeding from both the Father and Son.[24] The "begetting" does not refer to Mary's conceiving Jesus, but to a divine begetting before Creation.

In Reformed theology, the Trinity has special relevance to salvation, which is considered the result of an intra-Trinitarian covenant and in some way the work of each person. In its simplest form, the Father elects some to salvation before the foundation of the world, the Son performs the atonement for their sins, and the Spirit regenerates them so they can have faith in Christ, and sanctifies them.[25]

Christians believe the Holy Spirit inspired the Scriptures,[26] and that his active participation in a believer's life (even to the extent of "indwelling", or in a certain sense taking up residence within, the believer) is essential to living a Christian life.[27] In Catholic, Orthodox, and some Anglican theology, this indwelling in received through the sacrament called Confirmation or, in the East, Chrismation. Most Protestants believe that the Spirit indwells a new believer at the time of salvation. Pentecostal and Charismatic Protestants believe the baptism with the Holy Spirit is a distinct experience separate from other experiences like conversion, and many Pentecostals believe it will always—or at least usually—be evident through glossolalia (speaking in tongues).

Christians trace the orthodox formula of the Trinity — Father, Son, and Holy Spirit — back to the resurrected Jesus himself, who used this phrase in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:16–20).

Non-Trinitarians

In antiquity, and again following the Reformation until today, differing views existed concerning the Godhead from those of Trinitarians and the related traditional Christology. Though diverse, these views may be generally classified into those which hold Christ to be only divine and not differing from the Father hypostatically, and those which hold Christ to be less fully God than the Father, in the most extreme form being a mere human prophet. Ancient examples include the Gnostics, most of whom were for the divine and not human redeemer, generally disbelieving the reality of Christ's human flesh.[28][29] An example of the opposite view, the Arians considered Jesus a creature (created being) and thus substantially different from, and lower than the Father.[30] The antiquity of these views is witnessed by the early date to which they met condemnation. For example, the first epistle of John, in effect the earliest document to insist that the redeemer must be both human and divine, contains a sharp polemic against deniers of the flesh of Jesus.[31]

These views were rejected in antiquity by bishops such as Irenaeus and subsequently from the fourth century onwards condemned by various Ecumenical Councils. During the Reformation, though Roman Catholics, Greek Orthodox, and Protestants alike accepted the value of the first four great Councils of the Church, certain more radical groups viewed the era of Constantine and these councils as spiritually tainted, preferring alternative pre-conciliar views about the Godhead and considering the Trinity to be an unbiblical sham conjured during the years of the Church's decay.[32] Both of the differing views present in antiquity reappeared in Strassburg c. 1530. The view that Christ was only divine was first advanced by Clement Ziegler and expanded upon by Casper Schwenckfeld and the apocalyptic Melchior Hoffman. The view that Jesus was not God, but only a human prophet of God, was developed by Michael Servetus, though it appears just previously in trials of radicals at Augsburg in 1527.[33]

Present day views that Jesus is a created being include those of Jehovah's Witnesses.[34] Unitarians, descendants of Reformation era Socinians, view Jesus as never more than human.[35] Latter-day Saints accept the divinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, but deny that they have a common substance, believing them to be united only in will and purpose.[36] Modalists, such as Oneness Pentecostals, regard God as a single person, with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit considered modes or roles by which the unipersonal God expresses himself.[37]

Scriptures

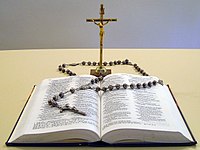

Christianity regards the Bible, a collection of canonical books in two parts, the Old Testament and the New Testament, as authoritative: written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and therefore the inerrant Word of God.[38] Protestants believe that the scriptures contain all revealed truth necessary for salvation (See Sola scriptura).[39]

The Old Testament contains the entire Jewish Tanakh, though in the Christian canon the books are ordered differently and some books of the Tanakh are divided into several books by the Christian canon. The Catholic and Orthodox canons include the Hebrew Jewish canon and other books (from the Septuagint Greek Jewish canon) which Catholics call Deuterocanonical, while Protestants consider the latter Apocrypha.[40]

The first four books of the New Testament are the Gospels, which tell of the life and teachings of Jesus. The four canonical books are Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The first three are often called synoptic because of the amount of material they share. The rest of the New Testament consists of a sequel to Luke's Gospel, the Acts of the Apostles, which describes the very early history of the Church, a collection of letters from early Christian leaders to congregations or individuals, the Pauline and General epistles, and the apocalyptic Book of Revelation.[40]

Some traditions maintain other canons. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church maintains two canons, the Narrow Canon, itself larger than any Biblical canon outside Ethiopia, and the Broad Canon, which has even more books.[41] The Latter-day Saints hold three additional books to be the inspired word of God: the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the Pearl of Great Price.[42]

Interpretation

Though Christians largely agree on the content of the Bible, no such consensus exists on the crucial matter of its interpretation, or exegesis. In antiquity, two schools of exegesis developed in Alexandria and Antioch. Alexandrine interpretation, exemplified by Origen, tended to read Scripture allegorically, while Antiochene interpretation insisted on the literal sense, holding that other meanings (called theoria) could only be accepted if based on the literal meaning.[43]

Catholic theology distinguishes two senses of scripture: the literal and the spiritual, the latter being subdivided into the allegorical, moral, and anagogical senses. The literal sense is "the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture and discovered by exegesis, following the rules of sound interpretation." The allegorical sense includes typology, for example the parting of the Red Sea is seen as a "type" of or sign of baptism;[44] the moral sense contains ethical teaching; the anagogical sense includes eschatology and applies to eternity and the consummation of the world.[45] Catholic theology also adds other rules of interpretation, which include the injunction that all other senses of sacred scripture are based on the literal,[46] that the historicity of the Gospels must be absolutely and constantly held,[47] that scripture must be read within the "living Tradition of the whole Church",[48] and that "the task of interpretation has been entrusted to the bishops in communion with the successor of Peter, the Bishop of Rome."[49]

Many Protestants stress the literal sense or historical-grammatical method,[50] even to the extent of rejecting other senses altogether. Martin Luther advocated "one definite and simple understanding of Scripture".[51] Other Protestant interpreters still make use of typology.[52] Protestants characteristically believe that ordinary believers may reach an adequate understanding of Scripture because Scripture itself is clear (or "perspicuous"), because of the help of the Holy Spirit, or both. Martin Luther believed that without God's help Scripture would be "enveloped in darkness",[51] but John Calvin wrote, "all who refuse not to follow the Holy Spirit as their guide, find in the Scripture a clear light."[53] The Second Helvetic Confession said, "we hold that interpretation of the Scripture to be orthodox and genuine which is gleaned from the Scriptures themselves (from the nature of the language in which they were written, likewise according to the circumstances in which they were set down, and expounded in the light of like and unlike passages and of many and clearer passages)." The writings of the Church Fathers, and decisions of Ecumenical Councils, though "not despise[d]", were not authoritative and could be rejected.[54]

Creeds

Creeds, or concise doctrinal statements, began as baptismal formulas and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the fourth and fifth centuries. The earliest creeds still in common use are the Apostles' Creed (text in Latin and Greek, with English translations) or Paul's creed of 1 Cor 15:1–9.

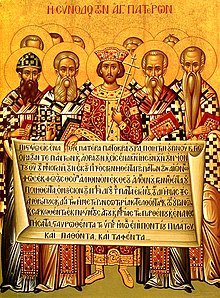

The Nicene Creed (Greek liturgical text, Latin liturgical text, English translations), largely a response to Arianism, was formulated at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively,[55] and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the Council of Ephesus in 431.[56]

A translation that, when published, was widely adopted by English-speaking Christians is that of the International Consultation on English Texts (ICET):

|

|

The phrases "God from God" and "and the Son" (the latter a matter of theological controversy and presented in brackets in the ICET translation) were not included in the text adopted by the First Council of Constantinople and confirmed by the Council of Ephesus, and as such are not used by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Chalcedonian Creed, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451,[57] (though not accepted by the Oriental Orthodox Churches)[58] taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, that both natures are perfect but are nevertheless perfectly united into one person.[59]

The Athanasian Creed (English translations), received in the western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons not dividing the Substance."[60]

Most Protestants accept the Creeds. Some Protestant traditions believe Trinitarian doctrine without making use of the Creeds themselves,[61] while other Protestants, like the Restoration Movement, stand against the use of creeds.

Eschaton and afterlife

Christians believe that upon (bodily) death the individual soul, considered to be immortal, experiences the particular judgment and is either elected for heaven or condemned to hell. The elect are called "saints" (Latin sanctus: "holy") and the process of being made holy is called sanctification. In Catholicism, those who die in a state of grace but with either unforgiven venial sins or incomplete penance undergo purification in purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into heaven.

At the last coming of Christ, the eschaton or end of time, all who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgement, whereupon Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[62]

Some groups do not distinguish a particular judgment from the general judgment at the end of time, teaching instead that souls remain in stasis until this time (see Soul sleep). These groups, and others that do not believe in the intercession of saints, generally do not employ the word "saint" to describe those in heaven. Universalists hold that eventually all will experience salvation, thereby rejecting the doctrine of the eternal damnation of hell.

Worship and practices

Christian life

Christians believe that all people should strive to live in imitation of Christ. This includes obedience to the Ten Commandments. Jesus taught that the greatest commandments were to: “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, soul, mind, and strength,” and to “love thy neighbor as thyself.”[63] This love includes such injunctions as "feed the hungry" and "shelter the homeless", and applies to friend or enemy alike. Though the relationship between charity and religious practice are sometimes taken for granted today, as Martin Goodman has observed, "charity in the Jewish and Christian sense was unknown to the pagan world."[64] Other Christian practice includes acts of piety such as prayer and Bible reading.

Christianity teaches that one can only overcome sin though divine grace: moral and spiritual progress can only occur with God's help through the gift of the Holy Spirit dwelling within the believer. Christians believe that by sharing in Christ's life, death, and resurrection, they die with him to sin and can be resurrected with him to new life.

Liturgical worship

Justin Martyr described second century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

- "And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need."[65]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the Gospels. Often these are arranged systematically around an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary. Instruction is given based on these readings, called a sermon, or, more specifically, a homily. There is a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung such as some hymns. Music may be accompanied by an organ and sung by choir. The Lord's Prayer, or Our Father, is regularly prayed. The Eucharist (also called Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper) consists of a ritual meal of consecrated bread and wine, discussed in detail below. Lastly, a collection occurs in which money is given by the congregation into a collection plate for the support of the Church and for charitable work of various types.

Some groups depart from this traditional liturgical structure. A division is often made between "High" church services, characterized by greater solemnity and ritual, and "Low" services, but even within these two categories there is great diversity in forms of worship. Seventh-day Adventists meet on Saturday (the original Sabbath), while others do not meet on a weekly basis. Charismatic or Pentecostal congregations may spontaneously feel led by the Holy Spirit to action rather than follow a formal order of service, including spontaneous prayer. Quakers sit quietly until moved by the Holy Spirit to speak. Some Evangelical services resemble concerts with rock and pop music, dancing, and use of multimedia. For groups without a priesthood the services are generally lead by a minister, preacher, or pastor. Still others may lack formal leaders, either in principle or by local necessity. Some churches use only a cappella music, either on principle (e.g. many Churches of Christ object to the use of instruments in worship) or by tradition (as in Orthodoxy).

Worship can be varied for special events like baptisms or weddings in the service or significant feast days. In the early church Christians and those yet to complete initiation would separate for part of the worship. In many churches today, adults and children will separate for all or some of the service to receive age-appropriate teaching. Such children's worship is often called Sunday school or Sabbath school.

Sacraments

A sacrament is a Christian rite that is an outward sign of an inward grace, instituted by Christ to sanctify humanity. Catholic, Orthodox, and Anglo-Catholics describe Christian worship in terms of seven sacraments: Baptism, Confirmation or Chrismation, Eucharist (communion), Penance (reconciliation), Anointing of the Sick (last rites), Holy Orders (ordination), and Matrimony.[66] Many Protestant groups, following Martin Luther,[67] recognize the sacramental nature of baptism and Eucharist, but not usually the other five in the same way, while other Protestant groups reject sacramental theology. Latter-day saint worship emphasizes the symbolic role of rites, calling some 'ordinances'. Though not sacraments, Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Holiness Churches emphasize "gifts of the Spirit" such as spiritual healing, prophecy, exorcism, glossolalia (speaking in tongues), and laying on of hands where God's grace is mysteriously manifest.

Eucharist

The Eucharist (also called Holy Communion, or the Lord's Supper) is the part of liturgical worship that consists of a consecrated meal usually ritualised as bread and wine. Justin Martyr described the Eucharist as follows:

- And this food is called among us Eukaristia [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.[68]

Orthodox, Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and many Anglicans believe that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ (the doctrine of the Real Presence). Most other Protestants, especially Reformed, believe the bread and wine represent the body and blood of Christ. These Protestants may celebrate it less frequently, whilst in Catholicism the Eucharist is celebrated daily. Catholic and Orthodox view communion as indicating those who are already united in the church, restricting participation to their members not in a state of mortal sin. In some Protestant churches participation is by prior arrangement with a church leader. Other churches view communion as a means to unity, rather than an end, and invite all Christians or even anyone to participate. They are more likely to celebrate it as an actual meal to feed hungry people.

Liturgical Calendar

In the New Testament Paul of Tarsus organised his missionary travels around the celebration of Pentecost. (Acts 20.16 and 1 Corinthians 16.8) This practice draws from Jewish tradition, with such feasts as the Feast of Tabernacles, the Passover, and the Jubilee. Today Catholics, Eastern Christians, and traditional Protestant communities frame worship around a liturgical calendar, which consists of a set of cycles of liturgical seasons observed annually. This includes holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus or the saints, periods of fasting such as Lent, and other pious events such as memoria or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Some Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. A few churches make no use of a liturgical calendar.

Symbols

Today the best-known Christian symbol is the cross, which refers to the method of Jesus' execution.[69] Several varieties exist, with some denominations tending to favor distinctive styles: Catholics the crucifix, Orthodox the crux orthodoxa, and Protestants an unadorned cross. An earlier Christian symbol was the 'ichthys' fish symbol and annagram. Other text based symbols include 'IHS' (the first three letters of 'Jesus' in Greek) and 'chi-rho' (the first two letters of the word Christ in Greek). In a modern Roman alphabet, the Chi-Rho appears like an X (Chi - χ) with a large P (Rho - ρ) overlaid and above it. It is said Constantine saw this symbol prior to converting to Christianity (see History and origins section below). Another ancient symbol is an anchor, which denotes faith and can incorporate a cross within its design.

History and origins

Christianity spread beyond its origins within the Jewish religion in the mid-first century under the leadership of the Apostles, especially Peter and Paul. Within a generation an episcopal hierarchy can be seen, and this would form the structure of the Church.[70]Christianity spread east to Asia and throughout the Roman Empire, despite persecution by the Roman Emperors until its legalization by Emperor Constantine in the early fourth century. During his reign, questions of orthodoxy lead to the convocation of the first Ecumenical Council, that of Nicaea.

In 391 Theodosius I established Nicene Christianity as the official and, except for Judaism, only legal religion in the Roman Empire. Later, as the political structure of the empire collapsed in the West, the Church assumed political and cultural roles previously held by the Roman aristocracy. Eremitic and Coenobitic monasticism developed, originating with the hermit St Anthony of Egypt around 300. With the avowed purpose of fleeing the world and its evils in contemptu mundi, the institution of monasticism would become a central part of the medieval world.[71]

During the Migration Period of Late Antiquity, various Germanic peoples adopted Christianity. Meanwhile, as western political unity dissolved, the linguistic divide of the Empire between Latin-speaking West and the Greek-speaking East intensified. By the Middle Ages distinct forms of Latin and Greek Christianity increasingly separated until cultural differences and disciplinary disputes finally resulted in the Great Schism (conventionally dated to 1054), which formally divided Christendom into the Catholic west and the Orthodox east. Western Christianity in the Middle Ages was characterized by cooperation and conflict between the secular rulers and the Church under the Pope, and by the development of scholastic theology and philosophy.

Beginning in the 7th century, Islam began a long series of military conquests of Christian areas, and it quickly conquered areas of the Byzantine Empire, Asia Minor, Palestine, Syria, Egypt, North Africa, and even southern Spain. Numerous military struggles followed, including the Crusades, the Spanish Reconquista, the Fall of Constantinople and the aggression of the Turks.

In the early sixteenth century, increasing discontent with corruption and immorality among the clergy resulted in attempts to reform the Church and society. The Protestant Reformation began after Martin Luther published his 95 theses in 1517, whilst the Roman Catholic Church experienced internal renewal with the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent (1545-1563). During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states. Meanwhile, partly from missionary zeal, but also under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

In the Modern Era, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies such as liberalism, nationalism, and socialism. This included the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and general hostility of Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution.

Persecution

Christians have frequently suffered from persecution. Starting with Jesus, persecution was a feature of the Church at its earliest beginnings. Notable early Christians such as Stephen, Paul, and, according to tradition, 10 out of the 11 remaining disciples of Jesus, were all executed. Adherence to Christianity was declared illegal within the Roman Empire, and, especially in the 3rd century, the Emperors demanded that their subjects (save only the Jews) participate in the imperial cult, where ritual sacrifices were made in worship of the traditional Roman gods and the Emperor, a practice incompatible with monotheistic Christianity.[72] Refusal to participate was considered akin to treason, punishable by death. Systematic state persecution of Christians culminated in the Great Persecution of Diocletian and ended with the Edict of Milan.[73]

Persecution of Christians persisted or even intensified in other places, such as in Sassanid Persia.[74] Later, under Islam, Christians were subjected to social and legal proscriptions[75] and at times also suffered violent persecution or confiscation of their property,[76] although that was not typical.[77]

There was some persecution of Christians after the French Revolution during the attempted Dechristianisation of France.[78] State restrictions on Christian practices today are generally associated with those authoritarian governments which either support a majority religion other than Christianity (as in Muslim states),[79] or tolerate only churches under government supervision, sometimes while officially promoting state atheism (as in North Korea). For example, the People's Republic of China allows only government-regulated churches and has regularly suppressed house churches or underground Catholics. The public practice of Christianity is outlawed in Saudi Arabia. On a smaller scale, Greek and Russian governmental restrictions on non-Orthodox religious activity occur today.

Complaints of discrimination have also been made by Christians in various other contexts. In some parts of the world, there is persecution of Christians by dominant religious groups or political groups. Many Christians are threatened, discriminated against, jailed, or even killed for their faith. Christians are persecuted today in many areas of the world including Cuba, the Middle East, North Korea, China, the Sudan, and Kosovo.[80]

Christians have also been perpetrators of persecution, which has been directed against members of other religions and against other Christians. Christian mobs, sometimes with government support, have destroyed pagan temples and oppressed adherents of paganism (such as the philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria, who was murdered by a Christian mob). Jewish communities have periodically suffered violence at Christian hands. Christian governments have suppressed or persecuted groups seen as heretical, later in cooperation with the Inquisition. Later denominational strife has sometimes escalated into religious wars. Witch hunts, carried out by secular authorities or popular mobs, were a frequent phenomenon in parts of early modern Europe and, to a lesser degree, North America.

Current controversies and criticisms

- See also: Criticism of Christianity

- See also: Criticism of the Bible

There are many controversies surrounding Christianity as to its influences and history.

- A few writers propose that Jesus is a myth, though historians generally agree that Jesus existed and have aimed at reconstructing the historical Jesus.

- Several writers have argued that various mystery religions, rather than historical events, may have been the inspiration for Christianity, especially myths about a gods or other figures said to have been killed and thereafter raised. In some cases, initiates in a mystery religion are said to have shared in the god's death, and in his immortality through his resurrection.[81] For example, Egyptologist E. A. Wallis Budge compared Christianity to the cult of Osiris.[82]

- Some writers consider Paul to be the founding figure of Christianity as opposed to Jesus, pointing to the extent of his writings and the scope of his missionary work.[83] See also Pauline Christianity.

- Members of the Jesus Seminar, and other Biblical scholars, have argued that the historical Jesus never claimed to be divine. They also reject the historicity of several other gospel themes including the empty tomb and thus a bodily resurrection. They assert that Gospel accounts describing these things are probably literary fabrications.[84]

- Adherents of Judaism generally believe that followers of Christianity misinterpret passages from the Old Testament, or Tanakh;[citation needed] for example, some Jewish interpreters consider that the reference to the coming Jewish Messiah in Daniel 9:25 was actually a reference to Cyrus the Great [citation needed] (called a messiah in Isa 45:1) who decreed the building of the Second Temple. (See also Judaism and Christianity.)

- Muslims believe that the Christian doctrine of the Trinity is incompatible with monotheism, and they reject the Christian teaching that Jesus is the Son of God, though they affirm the virgin birth and view him as a prophet preceding Muhammad.[85] The Qur'an also uses the title "Messiah", though with a different meaning.[86][87] Muslims also dispute the historical occurrence of the crucifixion of Jesus.[88]

See also

History and denominations

|

|

|

Notes

- ^ The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume IX, Monotheism; William F. Albright, From the Stone Age to Christianity; H. Richard Niebuhr, Radical Monotheism and Western Culture; About.com, Monotheistic Religion resources; Jonathan Kirsch, God Against the Gods; Linda Woodhead, An Introduction to Christianity; The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia Monotheism; The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, monotheism; New Dictionary of Theology, Paul pp. 496-99; David Vincent Meconi, "Pagan Monotheism in Late Antiquity" in Journal of Early Christian Studies pp. 111–12

- ^ Dictionary.com, Christianity

- ^ a b c d e Adherents.com, Religions by Adherents

- ^ WorthyNews.com, Growth of Christianity in China; LutherProduction.com, Growth in South Korea; Xhist.com, History of Christianity in Korea

- ^ 3:1 Acts 3:1; 5:27 – 42 Acts 5:27–42; 21:18 – 26 Acts 21:18–26; 24:5 Acts 24:5; 24:14 Acts 24:14; 28:22 Acts 28:22; 1:16 Romans 1:16; Tacitus, Annales xv 44; Josephus Antiquities xviii 3; Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience Volume II chapter 5; The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion page 158.

- ^ E. Peterson, "Christianus" pp. 353-72

- ^ Walter Bauer, Greek-English Lexicon; Ignatius Letter to the Magnesians 10, Letter to the Romans (Roberts-Donaldson tr., Lightfoot tr., Greek-text). However, an edition presented on some websites, one that otherwise corresponds exactly with the Roberts-Donaldson translation, renders this passage to the interpolated inauthentic longer recension of Ignatius's letters, which does not contain the word "Christianity".

- ^ S. E. Ahlstrom characterized denominationalism in America as “a virtual ecclesiology” that “first of all repudiates the insistences of the Roman Catholic church, the churches of the ‘magisterial’ Reformation, and of most sects that they alone are the true Church." Ahlstrom p. 381. For specific citations, on the Roman Catholic Church see the Catechism of the Catholic Church §816; other examples: Donald Nash, Why the Churches of Christ are not a Denomination; Wendell Winkler, Christ's Church is not a Denomination; and David E. Pratt, What does God think about many Christian denominations?

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, Christianity

- ^ Nichols, Rome and the Eastern Churches, pp. 27-52

- ^ Confessionalism is a term employed by historians to describe "the creation of fixed identities and systems of beliefs for separate churches which had previously been more fluid in their self-understanding, and which had not begun by seeking separate identities for themselves — they had wanted to be truly Catholic and reformed." MacCulloch, Reformation p. xxiv

- ^ Thus distinguishing themselves, though "not too much", from "Roman" Catholics — MacCulloch Reformation p. 510

- ^ Ahlstrom's summary is as follows: Restorationism has its genesis with Thomas and Alexander Campbell, whose movement is connected to the German Reformed Church through Otterbein, Albright, and Winebrenner (p. 212). American Millennialism and Adventism, which arose from Evangelical Protestantism, produced certain groups such as Mormonism (p. 387, 501-9), the Jehovah's Witness movement (p. 807), and, as a reaction specifically to William Miller, Seventh Day Adventism (p. 381).

- ^ Statistical Report: Annual Council of the General Conference Committee Silver Spring, Marlyand, October 6—11, 2006]

- ^ JW-Media.org Membership 2005

- ^ Jewfaq.org, The Messiah

- ^ Gospelcom.net, The Most Important Event in History; World-faiths.com, Christianity; Hank Hanegraaff, Resurrection: The Capstone in the Arch of Christianity

- ^ According to the Synoptics Gospels, this occurred in the last week of Jesus' life, but John narrates the event early in his account of Jesus' ministry.

- ^ 28:19 Matthew 28:19

- ^ 6:23 Romans 6:23, 2:8-9 Ephesians 2:8–9

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Grace and Justification

- ^ Westminster Confession , Chapter X; Charles Spurgeon, A Defense of Calvinism

- ^ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 87-90; T. Desmond Alexander, New Dictionary of Biblical Theology pp. 514-515; Alister E. McGrath, Historical Theology p. 61.

- ^ Vladimir Lossky God in Trinity; Loraine Boettner, One Substance, Three Persons

- ^ John Hendryx, The Work of the Trinity in Monergism

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic, Sacred Scripture; Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy , online text; timothy 3:16 2_Timothy 3:16; peter 1:21 2_Peter 1:21

- ^ 16:7-14 John 16:7–14; corinthians 2:10ff 1_Corinthians 2:10

- ^ Chadwick, East and West p. 5

- ^ earlychristianwritings.com, Gnostics, Gnostic Gospels, & Gnosticism; J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 22-28.

- ^ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 226-231; other similar ancient views include Adoptionists, ibid. pp. 115-119

- ^ Chadwick, East and West p. 5

- ^ MacCulloch, Reformation pp. 185, 187

- ^ MacCulloch, Reformation pp. 186-8

- ^ Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania, What Does the Bible Say About God and Jesus?

- ^ On Unitarians, see: UUA.org, Unitarian Views of Jesus; on connection with Socinianism, see: sullivan-county.com, Socinianism: Unitarianism in 16th-17th Century Poland and Its Influence (Note that the icon at the top of the page expresses Trinitarian theology with a symbolic hand gesture); on this matter they parallel the ancient Ebionites, see: J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 139

- ^ Hinckley, Gordon (March, 1998). "First Presidency Message: The Father, Son, and Holy Ghost". Ensign. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ William Arnold, Is Jesus God the Father?; in this way they parallel ancient Sabellians, see: J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 119-123; Robert Letham, The Holy Trinity: In Scripture, History, Theology, and Worship pp. 97-98

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Inspiration and Truth of Sacred Scripture (§105-108); Second Helvetic Confession, Of the Holy Scripture Being the True Word of God; Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, online text

- ^ Thirty-nine Articles, Art. VI; Westminster Catechism, Q. 3; James White, Does The Bible Teach Sola Scriptura?

- ^ a b F.F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture; Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Canon of Scripture § 120; Thirty-nine Articles, Art. VI

- ^ Ethiopian Orthodox Old Testament, The Bible: The Book That Bridges the Millennia

- ^ The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, The Scriptures, Internet Edition

- ^ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines pp. 69-78.

- ^ corinthians 10:2 1_Corinthians 10:2

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture § 115-118

- ^ Thomas Aquinas, Whether in Holy Scripture a word may have several senses?; c.f. Catechism of the Catholic Church, §116

- ^ Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum (V.19)

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Holy Spirit, Interpreter of Scripture § 113

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, The Interpretation of the Heritage of Faith § 85

- ^ R.C. Sproul, Knowing Scripture pp. 45-61; Greg Bahnsen, A Reformed Confession Regarding Hermeneutics (art. 6)

- ^ a b Scott Foutz, Martin Luther and Scripture

- ^ E.g., in his commentary on Matthew 1 (§III.3) Matthew Henry writes:

- Phares and Zara, the twin-sons of Judah, are likewise both named, though Phares only was Christ's ancestor, for the same reason that the brethren of Judah are taken notice of; and some think because the birth of Phares and Zara had something of an allegory in it. Zara put out his hand first, as the first-born, but, drawing it in, Phares got the birth-right. The Jewish church, like Zara, reached first at the birthright, but through unbelief, withdrawing the hand, the Gentile church, like Phares, broke forth and went away with the birthright; and thus blindness is in part happened unto Israel, till the fulness of the Gentiles become in, and then Zara shall be born — all Israel shall be saved, Rom. 11:25, 26.

- ^ John Calvin, Commentaries on the Catholic Epistles 2 Peter 3:14-18

- ^ Second Helvetic Confession, Of Interpreting the Holy Scriptures; and of Fathers, Councils, and Traditions

- ^ Catholics United for the Faith, We Believe in One God; Encyclopedia of Religion, Arianism

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia (vol. 5), Council of Ephesus

- ^ Matt Slick, Chalcedonian Creed; Christian History Institute, First Meeting of the Council of Chalcedon

- ^ British Orthodox Church, The Oriental Orthodox Rejection of Chalcedon

- ^ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia (vol. 2) Athanasian Creed

- ^ E.g., The Southern Baptist Convention gives no official status to any of the ancient creeds, but the Baptist Faith and Message says:

- The eternal triune God reveals Himself to us as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with distinct personal attributes, but without division of nature, essence, or being.

- ^ See, e.g., Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99; and John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book Three, Ch. 25.

- ^ 22:37-40 matthew 22:37–40

- ^ Martin Goodman, The Ruling Class of Judaea: The Origins of the Jewish Revolt Against Rome AD 66-70, Cambridge University Press, p.65

- ^ Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- ^ For Catholicism: see Catechism of the Catholic Church §1210

- ^ Martin Luther, Small Catechism

- ^ Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII

- ^ Catholic-reources.org, Christian Symbols

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia, Canons of the Council of Nicaea, especially canon 6.

- ^ Jo Ann H. Moran Cruze and Richard Gerberding, Medieval Worlds pp. 118-119

- ^ Religionfacts.com, Persecution in the Early Church

- ^ ChristianityToday.com 313 The Edict of Milan

- ^ Macro History, The Sassanids to 500 CE

- ^ While they could legally practice their faith, this was subject to various restrictions: The performance of religious rituals had to be in a manner inconspicuous to Muslims, and they were prohibited from proselytizing.(Lewis (1984) p. 26)

- ^ Bernard Lewis wrote: "Sometimes, when a persecution occurred, we find that the instigators were concerned to justify it in terms of the Holy Law. The usual argument was that the Jews or the Christians had violated the pact by overstepping their proper place. They had thus broken the conditions of the contract with Islam, and the Muslim state and people were no longer bound by it."; see also Bat Ye'or, The Decline of Eastern Christianity Under Islam.

- ^ Lewis, The Jews of Islam p. 44; Lewis (1984, p. 8.) states that "persecution in the form of violent and active repression was rare and atypical".

- ^ Mortimer Chambers, The Western Experience (vol. 2) chapter 21

- ^ Paul Marshall, Their Blood Cries Out; Worldnetdaily.com, Christians persecuted in Islamic nations

- ^ see persecution.org;christianmonitor.org; and Cliff Kincaid, aim.org Christians Under Siege in Kosovo

- ^ Kenneth Latourette, Christianity p. 394

- ^ E. A. Wallis Budge, Egyptian Religion

- ^ David Wenham, Paul: Follower of Jesus or Founder of Christianity?

- ^ "The empty tomb is a fiction -- Jesus did not raise (sic) bodily from the dead." front flap of Acts of Jesus.

- ^ Gary Miller, A concise reply to Christianity.

- ^ The Holy Qura'an, 3:46.

- ^ Mike Tabish,What does the Qur'an say about Isa (Jesus)?

- ^ Answering-Christianity.com, What does the Holy Qur'an say about Jesus (peace be upon him).

Bibliography

Primary sources

|

A

B

C

D

G

H

I

|

J

L

M

N

P

S

T

U

W

|

Secondary sources

|

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

J

K

|

L

M

N

O

P

R

S

T

V

W

Y

Z

|

Popular Media

|

B

C

D

E

F

E

G

J

|

K

M

O

P

R

S

T

W

|

Further reading

- From Jesus to Christ Perspectives on Jesus and early Christianity from various academics.

- bethinking.org Christianity Treating Christianity as a whole worldview or perspective and looking at the relationship between historic Christianity and contemporary thought.

- Asia is becoming one of the largest Christian populations in the world in the next 30 years.

- "Christianity". Religion & Ethics. BBC. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- The Bible And Christianity - The Historical Origins An essay by Scott Bidstrup.

- Gillian Clark, Christianity and Roman Society, Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-63386-9

External links

- Bible Gateway The Bible online.

- New Advent A collection of resources including the Church Fathers, the Summa Theologica, the Catholic Encyclopedia, and others.

- Monergism.com Theological articles grouped by topic.

- ReligionFacts.com: Christianity Fast facts, glossary, timeline, history, beliefs, texts, holidays, symbols, people, etc.

- WikiChristian, a wiki book on Christianity, church history and doctrine, and Christian art and music

- Syriac Orthodox Resources Large compendium of information and links relating to Oriental Orthodoxy.Template:Link FATemplate:Link FATemplate:Link FA