Arabic: Difference between revisions

m robot Adding: nrm:Arabe |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{sprotect}} |

|||

{{redirect|Arabic}} |

{{redirect|Arabic}} |

||

{{Infobox Language|name=Arabic |

{{Infobox Language|name=Arabic |

||

Revision as of 23:59, 8 January 2007

Arabic (اللغة العربية Template:ArabDIN or just عربي Template:ArabDIN) is the largest living member of the Semitic language family in terms of speakers. Classified as Central Semitic, it is closely related to Hebrew and Aramaic. Modern Arabic is classified as a macrolanguage with 27 sub-languages in ISO 639-3. These varieties are spoken throughout the Arab world, and Standard Arabic is widely studied and known throughout the Islamic world.

Modern Standard Arabic derives from Classical Arabic, the only surviving member of the Old North Arabian dialect group, attested epigraphically since the 6th century, which has been a literary language and the liturgical language of Islam since the 7th century.

Because of its liturgical role, Arabic has lent many words to other Islamic languages, akin to the role Latin has in Western European languages. During the Middle Ages Arabic was also a major vehicle of culture, especially in science, mathematics and philosophy, with the result that many European languages have also borrowed numerous words from it.

Literary and Modern Standard Arabic

The term "Arabic" may refer either to literary Arabic (fuṣḥā) or to the many localized varieties of Arabic commonly called "colloquial Arabic." Arabs consider literary Arabic as the standard language and tend to view everything else as mere dialects. Literary Arabic (اللغة العربية الفصيحة translit: Template:ArabDIN "the most eloquent Arabic language"), refers both to the language of present-day media across North Africa and the Middle East and to the language of the Qur'an. (The expression media here includes most television and radio, and practically all written matter, including all books, newspapers, magazines, documents of every kind, and reading primers for small children.) "Colloquial" or "dialectal" Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties derived from Classical Arabic, spoken daily across North Africa and the Middle East, which constitute the everyday spoken language. These sometimes differ enough to be mutually incomprehensible. These dialects are not typically written, although a certain amount of literature (particularly plays and poetry) exists in many of them. They are often used to varying degrees in informal spoken media, such as soap operas and talk shows. Literary Arabic or classical Arabic is the official language of all Arab countries and is the only form of Arabic taught in schools at all stages.

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia–the normal use of two separate varieties of the same language, usually in different social situations. In the case of Arabic, educated Arabs of any nationality can be assumed to speak both their local dialect and their school-taught literary Arabic (to an equal or lesser degree). This diglossic situation facilitates code switching in which a speaker switches back and forth unaware between the two varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. In instances in which highly educated Arabs of different nationalities engage in conversation only to find their dialects mutually unintelligible (e.g. a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), both should be able to code switch into Literary Arabic for the sake of communication.

Like other languages, literary Arabic continues to evolve and one can distinguish Classical Arabic (especially from the pre-Islamic to the Abbasid period, including Qur'anic Arabic) and Modern Standard Arabic as used today. Classical Arabic is considered normative; modern authors attempt (with varying degrees of success) to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by Classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh), and to use the vocabulary defined in Classical dictionaries (such as the Lisan al-Arab.) However, the exigencies of modernity have led to the adoption of numerous terms which would have been mysterious to a Classical author, whether taken from other languages (eg فيلم film) or coined from existing lexical resources (eg هاتف hātif "telephone" < "caller"). Structural influence from foreign languages or from the colloquials has also affected Modern Standard Arabic: for example, MSA texts sometimes use the format "X, X, X, and X" when listing things, whereas Classical Arabic prefers "X and X and X and X", and subject-initial sentences are significantly more common in MSA than in Classical Arabic. For these reasons, Modern Standard Arabic is generally treated separately in non-Arab sources.

The influence of Arabic on other languages

The influence of Arabic has been most profound in those countries dominated by Islam or Islamic power. Arabic is a major source of vocabulary for languages as diverse as Berber, Kurdish, Persian, Swahili, Urdu, Hindi (especially the spoken variety), Turkish, Malay, and Indonesian, as well as other languages in countries where these languages are spoken. For example the Arabic word for book /kita:b/ is used in all the languages listed, apart from Malay and Indonesian (where it specifically means "religious book").

The terms borrowed range from religious terminology (like Berber taẓallit "prayer" < salat), academic terms (like Uyghur mentiq "logic"), economic items (like English "sugar") to placeholders (like Spanish fulano "so and so") and everyday conjunctions (like Urdu lekin "but".) Most Berber varieties (such as Kabyle), along with Swahili, borrow some numbers from Arabic. Most religious terms used by Muslims around the world are direct borrowings from Arabic, such as salat 'prayer' and imam 'prayer leader'. In languages not directly in contact with the Arab world, Arabic loanwords are often mediated by other languages rather than being transferred directly from Arabic; for example, most Arabic loanwords in Urdu entered through Persian, and many older Arabic loanwords in Hausa were borrowed from Kanuri.

In common with other European languages, many English words are derived from Arabic, often through other European languages, especially Spanish and Italian. Among them every-day vocabulary like "sugar" (sukkar), "cotton" (quṭn) or "magazine" ([[makhzen|Template:ArabDIN]]). More recognizable are words like "algebra", "alcohol", "alchemy", "alkali" and "zenith" (see list of English words of Arabic origin).

Arabic and Islam

The Qur'an is expressed in Arabic and traditionally Muslims deem it impossible to translate in a way that would adequately reflect its exact meaning—indeed, until recently, some schools of thought maintained that it should not be translated at all. A list of Islamic terms in Arabic covers those terms which are used by all Muslims, whatever their mother tongue. While Arabic is strongly associated with Islam (and is the language of salah, prayer), it is also spoken by Arab Christians, Mizrahi Jews, and smaller sects such as Iraqi Mandaeans.

A majority of the world's Muslims do not speak Arabic, but only know some fixed phrases of the language, such as those used in Islamic prayer, without necessarily knowing their meaning. However, learning Arabic is an essential part of the curriculum for anyone attempting to become an Islamic religious scholar.

History

The earliest Proto-Arabic, or Ancient North Arabian, texts are the Hasaean inscriptions of eastern Saudi Arabia, from the 8th century BC, written not in the modern Arabic alphabet, nor in its Nabataean ancestor, but in variants of the epigraphic South Arabian musnad. These are followed by 6th-century BC Lihyanite texts from southeastern Saudi Arabia and the Thamudic texts found throughout Arabia and the Sinai, and not in reality connected with Thamud. Later come the Safaitic inscriptions beginning in the 1st century BC, and the many Arabic personal names attested in Nabataean inscriptions (which are, however, written in Aramaic). From about the 2nd century BC, a few inscriptions from Qaryat al-Faw (near Sulayyil) reveal a dialect which is no longer considered "Proto-Arabic", but Pre-Classical Arabic.

By the fourth century AD, the Arab kingdoms of the Lakhmids in southern Iraq, the Ghassanids in southern Syria the Kindite Kingdom emerged in Central Arabia. Their courts were responsible for some notable examples of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry, and for some of the few surviving pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions in the Arabic alphabet.

Dialects and descendants

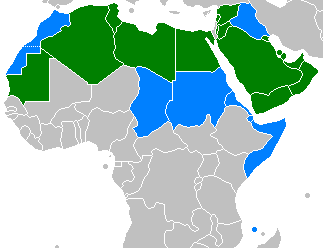

"Colloquial Arabic" is a collective term for the spoken languages or dialects of people throughout the Arab world, which, as mentioned, differ radically from the literary language. The main dialectal division is between the North African dialects and those of the Middle East, followed by that between sedentary dialects and the much more conservative Bedouin dialects. Speakers of some of these dialects are unable to converse with speakers of another dialect of Arabic; in particular, while Middle Easterners can generally understand one another, they often have trouble understanding North Africans (although the converse is not true, due to the popularity of Middle Eastern—especially Egyptian—films and other media).

One factor in the differentiation of the dialects is influence from the languages previously spoken in the areas, which have typically provided a significant number of new words, and have sometimes also influenced pronunciation or word order; however, a much more significant factor for most dialects is, as among Romance languages, retention (or change of meaning) of different classical forms. Thus Iraqi aku, Levantine fīh, and North African kayən all mean "there is", and all come from classical Arabic forms (yakūn, fīhi, kā'in respectively), but now sound very different.

The major groups are:

- Egyptian Arabic مصري : Spoken by about 76 million people in Egypt and perhaps the most widely understood variety, thanks to the popularity of Egyptian-made films and TV shows

- Maghreb Arabic مغربي (Algerian Arabic, Moroccan Arabic, Tunisian Arabic, Maltese and western Libyan Arabic) The Moroccan and Algerian dialects are each spoken by about 20 million people.

- Levantine Arabic شامي (Western Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian, western Jordanian and Cypriot Maronite Arabic)

- Iraqi Arabic عراقي (and Khuzestani Arabic) - with significant differences between the more Arabian-like gilit-dialects of the south and the more conservative qeltu-dialects of the northern cities

- East Arabian Arabic (Eastern Saudi Arabia, Western Iraq, Eastern Syrian , Jordanian and parts of Oman)

- Gulf Arabic or Khaleeji (Arabic script: خليجي) (Bahrain, Saudi Eastern Province, Kuwait, UAE, Qatar, and Oman)

Other varieties include:

- Ḥassānīya (in Mauritania and western Sahara)

- Sudanese Arabic (with a dialect continuum into Chad)

- Hijazi Arabic حجازي (west coast of Saudi Arabia, Northern Saudi Arabia, eastern Jordan, Western Iraq)

- Najdi Arabic نجدي (Najd region of central Saudi Arabia)

- Yemeni Arabic يمني (Yemen to southern Saudi Arabia)

- Andalusi Arabic (Iberia until 17th century)

- Siculo Arabic (Sicily, South Italy until 14th century)

- Maltese, which is spoken on the Mediterranean island of Malta, is the only one to have established itself as a fully separate language, with independent literary norms. Apart from its phonology, Maltese bears considerable similarity to urban varieties of Tunisian Arabic, however in the course of history, the language has adopted numerous loanwords, phonetic and phonological features, and even some grammatical patterns, from Italian, Sicilian, and English. It is also the only Semitic tongue written in the Latin alphabet.

Sounds

The phonemes below reflect the pronunciation of Standard Arabic.

Vowels

Arabic has three vowels, with their long forms, plus two diphthongs: a [ɛ̈] (open e as in English bed, but centralised), i [ɪ], u [ʊ]; ā [æː], ī [iː], ū [uː]; ai (ay) [ɛ̈ɪ], au (aw) [ɛ̈ʊ]. Allophonically, after velarized consonants (see following), the vowel a is pronounced [ɑ], ā as [ɑː] (thus also after r), ai as [ɑɪ] and au as [ɑʊ].

Consonants

| Bilabial | Inter-dental | Dental (incl. alveolar) | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | ||||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | t̪ | t̪ˁ | k | q | ʔ | |||||

| voiced | b | d̪ | d̪ˁ | dʒ¹ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | θ | s | sˁ | ʃ | x | ħ | h | ||

| voiced | ð | z | ðˁ | ɣ | ʕ | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||||

| Lateral | l ² | ||||||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||||

| Approximant | w | j | |||||||||

See Arabic alphabet for explanations on the IPA phonetic symbols found in this chart.

- [dʒ] is pronounced as [ɡ] by some speakers. This is especially characteristic of the Egyptian and southern Yemeni dialects. In many parts of North Africa and in the Levant, it is pronounced as [ʒ].

- /l/ is pronounced [lˁ] only in /ʔalːɑːh/, the name of God, i.e. Allah, when the word follows a, ā, u or ū (after i or ī it is unvelarised: bismi l-lāh /bɪsmɪlːæːh/).

- /ʕ/ is usually a phonetic approximant.

- In many varieties, /ħ, ʕ/ are actually epiglottal [ʜ, ʢ] (despite what is reported in many earlier works).

Arabic has consonants traditionally termed "emphatic" /tˁ, dˁ, sˁ, ðˁ/ are both velarized [tˠ, dˠ, sˠ, ðˠ] and pharyngealised [tˁ, dˁ, sˁ, ðˁ]. This simultaneous velarization and pharyngealization is deemed "Retracted Tongue Root" by phonologists.[1] In some transcription systems, emphasis is shown by capitalizing the letter e.g. /dˁ/ is written ‹D›; in others the letter is underlined or has a dot below it e.g. ‹ḍ›.

Vowels and consonants can be (phonologically) short or long. Long (geminate) consonants are normally written doubled in Latin transcription (i.e. bb, dd, etc.), reflecting the presence of the Arabic diacritic mark shaddah, which marks lengthened consonants. Such consonants are held twice as long as short consonants. This consonant lengthening is phonemically contrastive: e.g. qabala "he received" and qabbala "he kissed".

Syllable structure

Arabic has two kinds of syllables: open syllables (CV) and (CVV) - and closed syllables (CVC), (CVVC) and (CVCC). Every syllable begins with a consonant - or else a consonant is borrowed from a previous word through elision – especially in the case of the definite article THE, al (used when starting an utterance) or _l (when following a word), e.g. baytu –l mudiir “house (of) the director”, which becomes bay-tul-mu-diir when divided syllabically. By itself, "the director" would be pronounced /al mudiːr/.

Stress

Although word stress is not phonemically contrastive in Standard Arabic, it does bear a strong relationship to vowel length and syllable shape, and correct word stress aids intelligibility. In general, "heavy" syllables attract stress (i.e. syllables of longer duration - a closed syllable or a syllable with a long vowel). In a word with a syllable with one long vowel, the long vowel attracts the stress (e.g. ki-'taab and ‘kaa-tib). In a word with two long vowels, the second long vowel attracts stress (e.g.ma-kaa-'tiib). In a word with a "heavy" syllable where two consonants occur together or the same consonant is doubled, the (last) heavy syllable attracts stress (e.g. ya-ma-’niyy, ka-'tabt, ka-‘tab-na, ma-‘jal-lah, ‘mad-ra-sah, yur-‘sil-na). This last rule trumps the first two: ja-zaa-ʔi-‘riyy. Otherwise, word stress typically falls on the first syllable: ‘ya-man, ‘ka-ta-bat, etc. The Cairo (Egyptian Arabic) dialect, however, has some idiosyncrasies in that a heavy syllable may not carry stress more than two syllables from the end of a word, so that mad-‘ra-sah carries the stress on the second-to-last syllable, as does qaa-‘hi-rah.

Dialectal variations

In some dialects, there may be more or fewer phonemes than those listed in the chart above. For example, non-Arabic [v] is used in the Maghreb dialects as well in the written language mostly for foreign names. Semitic [p] became [f] extremely early on in Arabic before it was written down; a few modern Arabic dialects, such as Iraqi (influenced by Persian) distinguish between [p] and [b].

Interdental fricatives ([θ] and [ð]) are rendered as stops [t] and [d] in some dialects (such as Levantine, Egyptian, and much of the Maghreb); some of these dialects render them as [s] and [z] in "learned" words from the Standard language. Early in the expansion of Arabic, the separate emphatic phonemes [dˁ] and [ðˁ] coallesced into a single phoneme, becoming one or the other. Predictably, dialects without interdental fricatives use [dˁ] exclusively, while those with such fricatives use [ðˁ]. Again, in "learned" words from the Standard language, [ðˁ] is rendered as [zˁ] (in the Middle East) or [dˁ] (in North Africa) in dialects without interdental fricatives.

Another key distinguishing mark of Arabic dialects is how they render Standard [q] (a voiceless uvular stop). It retains its original pronunciation in widely scattered regions such as Yemen, Morocco, and urban areas of the Maghreb. But it is rendered as a voiced velar stop [ɡ] in Gulf Arabic, Iraqi Arabic, Upper Egypt, much of the Maghreb, and less urban parts of the Levant (e.g. Jordan); as a voiced uvular constrictive [ʁ] in Sudanese Arabic; and as a glottal stop [ʔ] in several prestige dialects, such as those spoken in Cairo, Beirut and Damascus. Additionally, confessional differences may sometimes be distinguished: in the case of [q], some traditionally Christian villages in rural areas of the Levant render the sound as [k], as do Shia Bahrainis. Thus, Arabs instantly give away their geographical (and class) origin by their pronunciation of a word such as qamar "moon": [qamar], [ɡamar], [ʁamar], [ʔamar] or [kamar].

Grammar

Arabic has three grammatical cases roughly corresponding to: nominative, genitive and accusative, and three numbers: singular, dual and plural. Arabic has two genders, expressed by pronominal, verbal and adjectival agreement. Numerals may agree with the same or different gender depending on the number's amount.

As in many other Semitic languages, Arabic verb formation is based on a (usually) triconsonantal root, which is not a word in itself but contains the semantic core. The consonants Template:ArabDIN, for example, indicate 'write', Template:ArabDIN indicate 'read', Template:ArabDIN indicate 'eat' etc.; Words are formed by supplying the root with a vowel structure and with affixes. Traditionally, Arabic grammarians have used the root Template:ArabDIN 'do' as a template to discuss word formation. The personal forms a verb can take correspond to the forms of the pronouns, except that in the 3rd person dual, gender is differentiated, yielding paradigms of 13 forms.

Arabic has two verbal voices, active and passive. The passive voice is expressed by a change in vocalization and is normally not expressed in unvocalized writing.

Writing system

The Arabic alphabet derives from the Aramaic script (Nabataean), to which it bears a loose resemblance like that of Coptic or Cyrillic script to Greek script. Traditionally, there were several differences between the Western (North African) and Middle Eastern version of the alphabet—in particular, the fa and qaf had a dot underneath and a single dot above respectively in the Maghreb, and the order of the letters was slightly different (at least when they were used as numerals). However, the old Maghrebi variant has been abandoned except for calligraphic purposes in the Maghreb itself, and remains in use mainly in the Quranic schools (zaouias) of West Africa. Arabic, like other Semitic languages, is written from right to left.

Calligraphy

After the definitive fixing of the Arabic script around 786, by Khalil ibn Ahmad al Farahidi, many styles were developed, both for the writing down of the Qur'an and other books, and for inscriptions on monuments as decoration.

Arabic calligraphy has not fallen out of use as in the Western world, and is still considered by Arabs as a major art form; calligraphers are held in great esteem. Being cursive by nature, unlike the Latin alphabet, Arabic script is used to write down a verse of the Qur'an, a Hadith, or simply a proverb, in a spectacular composition. The composition is often abstract, but sometimes the writing is shaped into an actual form such as that of an animal. Two of the current masters of the genre are Hassan Massoudy and Khaled Al Saa’i.

Transliteration

There are a number of different standards of Arabic transliteration: methods of accurately and efficiently representing Arabic with the Latin alphabet. The more scientific standards allow the reader to recreate the exact word using the Arabic alphabet. However, these systems are heavily reliant on diacritical marks such as "š" for the English sh sound. At first sight, this may be difficult to recognize. Less scientific systems often use digraphs (like sh and kh), which are usually more simple to read, but sacrifice the definiteness of the scientific systems. In some cases, the sh or kh sounds can be represented by italicizing or underlining them -- that way, they can be distinguished from separate s and h sounds or k and h sounds, respectively. (Compare gashouse to gash.)

The system used by the US military, Standard Arabic Technical Transliteration System or SATTS, solves some of these issues, as well as the need for special characters by representing each Arabic letter with a unique symbol in the ASCII range to provide a one-to-one mapping from Arabic to ASCII and back. This system, while facilitating typing on English keyboards, presents its own ambiguities and disadvantages.

During the last few decades and especially since the 1990s, Western-invented text communication technologies have become prevalent in the Arab world, such as personal computers, the World Wide Web, email, Bulletin board systems, IRC, instant messaging and mobile phone text messaging. Most of these technologies originally had the ability to communicate using the Latin alphabet only, and some of them still do not have the Arabic alphabet as an optional feature. As a result, Arabic speaking users communicated in these technologies by transliterating the Arabic text using the Latin script, sometime known as IM Arabic.

To handle those Arabic letters that cannot be accurately represented using the Latin script, numerals and other characters were appropriated. For example, the numeral "3" may be used to represent the Arabic letter "ع", ayn. There is no universal name for this type of transliteration, but some have named it Arabic Chat Alphabet. Other systems of transliteration exist, such as using dots or capitalization to represent the "emphatic" counterparts of certain consonants. For instance, using capitalization, the letter "د", or daal, may be represented by d. Its emphatic counterpart, "ض", may be written as D.

References

- Edward William Lane, Arabic English Lexicon, 1893, 2003 reprint: ISBN 81-206-0107-6, 3064 pages (online edition).

- Hans Wehr, Arabisches Wörterbuch für die Schriftsprache der Gegenwart: Arabisch-Deutsch, Harassowitz, 1952, 1985 reprint: ISBN 3-447-01998-0, 1452 pages; English translation: Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, Harassowitz, 1961.

Phonology

- Thelwall, Robin (2003). "Arabic". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)

Grammar

- Kees Versteegh, The Arabic Language, Edinburgh University Press (1997). See online versions: [1] [2] [3] [4]

- Mumisa, Michael, Introducing Arabic, Goodword Books (2003).

Notes

- ^ Thelwall, 52

See also

- Varieties of Arabic

- Arabist

- Arabic literature

- Arabic alphabet

- List of Islamic terms in Arabic

- List of English words of Arabic origin

- List of French words of Arabic origin

- Arabic influence on Spanish

- List of common phrases in various languages

- Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic

External links

- "The Development of Classical Arabic" by Kees Versteegh

- Public Domain Arabic Language Courses

- Arabic for simple usage

- Center for Arabic Culture: Arabic Literature

- Arabic Calligraphy

- Arabic language pronunciation applet with audio samples

- Online Arabic keyboard