Chick Corea

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Chick Corea | |

|---|---|

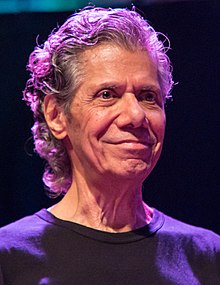

Corea in 2019 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Armando Anthony Corea |

| Born | June 12, 1941 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | February 9, 2021 (aged 79) Tampa Bay, Florida, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1962–2021[1] |

| Labels | |

| Website | chickcorea |

Armando Anthony "Chick" Corea (June 12, 1941 – February 9, 2021) was an American jazz composer, pianist, keyboardist, bandleader, and occasional percussionist.[2][3] His compositions "Spain", "500 Miles High", "La Fiesta", "Armando's Rhumba", and "Windows" are widely considered jazz standards.[4] As a member of Miles Davis's band in the late 1960s, he participated in the birth of jazz fusion. In the 1970s he formed Return to Forever.[3] Along with McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, and Keith Jarrett, Corea is considered to have been one of the foremost jazz pianists of the post-John Coltrane era.[5]

Corea continued to collaborate frequently while exploring different musical styles throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He won 27 Grammy Awards and was nominated more than 70 times for the award.[6]

Early life and education

Armando Corea was born in Chelsea, Massachusetts on June 12, 1941,[7] to parents Anna (née Zaccone) and Armando J. Corea.[2][8] He was of southern Italian descent, his father having been born to an immigrant from Albi comune, in the Province of Catanzaro in the Calabria region.[9][10] His father, a trumpeter who led a Dixieland band in Boston in the 1930s and 1940s, introduced him to the piano at the age of four.[11] Surrounded by jazz, he was influenced at an early age by bebop and Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Horace Silver, and Lester Young. When he was eight, he took up drums, which would influence his use of the piano as a percussion instrument.

Corea developed his piano skills while exploring music on his own. A notable influence was concert pianist Salvatore Sullo, from whom Corea began taking lessons at age eight; Sullo introduced him to classical music, helping spark his interest in musical composition. He also was a performer and soloist for several years in the St. Rose Scarlet Lancers, a drum and bugle corps based in Chelsea.

Given a black tuxedo by his father, he started playing gigs while still in high school. He enjoyed listening to Herb Pomeroy's band at the time and had a trio that played Horace Silver's music at a local jazz club. He eventually moved to New York City, where he studied music at Columbia University, then transferred to the Juilliard School. He quit both after finding them disappointing, but remained in New York.

Career

Corea began his professional recording and touring career in the early 1960s with Mongo Santamaria, Willie Bobo, Blue Mitchell, Herbie Mann, and Stan Getz. In 1966 he recorded his debut album, Tones for Joan's Bones which was not released until 1968. In 1968 he recorded and released a highly regarded trio album, Now He Sings, Now He Sobs, with drummer Roy Haynes and bassist Miroslav Vitouš.[3]

In 1968, Corea began recording and touring with Miles Davis, appearing on the widely praised Davis studio albums Filles de Kilimanjaro, In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew, and On the Corner. He appeared as well as the later compilation albums Big Fun, Water Babies, and Circle in the Round.

In concert performances he frequently processed the sound of his electric piano through a ring modulator. Utilizing the unique style, he appeared on multiple live Davis albums including Black Beauty: Live at the Fillmore West, and Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore East. His membership in the Davis band continued until 1970, with the final touring band he was part of consisting of saxophonist Steve Grossman, fellow pianist Keith Jarrett (here playing electric organ), bassist Dave Holland, percussionist Airto Moreira, drummer Jack DeJohnette, and Davis himself on trumpet.[3]

Holland and Corea departed the Davis group at the same time to form their own free jazz group, Circle, also featuring multireedist Anthony Braxton and drummer Barry Altschul. They were active from 1970 to 1971, and recorded on Blue Note and ECM. Aside from exploring an atonal style, Corea sometimes reached into the body of the piano and plucked the strings. In 1971, Corea decided to work in a solo context, recording the sessions that became Piano Improvisations Vol. 1 and Piano Improvisations Vol. 2 for ECM in April of that year.

The concept of communication with an audience became a big thing for me at the time. The reason I was using that concept so much at that point in my life–in 1968, 1969 or so–was because it was a discovery for me. I grew up kind of only thinking how much fun it was to tinkle on the piano and not noticing that what I did had an effect on others. I did not even think about a relationship to an audience, really, until way later.[12]

Jazz fusion

Named after their eponymous 1972 album, Corea's Return to Forever band relied on both acoustic and electronic instrumentation and initially drew upon Hispanic music styles more than rock music. On their first two records, the group consisted of Flora Purim on vocals and percussion, Joe Farrell on flute and soprano saxophone, Miles Davis bandmate Airto on drums and percussion, and Stanley Clarke on acoustic double bass.[3] Drummer Lenny White and guitarist Bill Connors later joined Corea and Clarke to form the second version of the group, which blended the earlier Latin music elements with rock and funk-oriented music partially inspired by the Mahavishnu Orchestra, led by his Bitches Brew bandmate John McLaughlin. This incarnation of the band recorded the album Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy, before Connors' replacement by Al Di Meola, who later played on Where Have I Known You Before, No Mystery and Romantic Warrior.

In 1976, Corea released My Spanish Heart, influenced by Hispanic music and featuring vocalist Gayle Moran (Corea's wife) and violinist Jean-Luc Ponty. The album combined jazz and flamenco, supported by Minimoog synthesizer and a horn section.

Duet projects

In the 1970s, Corea started working with vibraphonist Gary Burton, with whom he recorded several duet albums for ECM, including 1972's Crystal Silence. They reunited in 2006 for a concert tour. A new record called The New Crystal Silence was issued in 2008 and won a Grammy Award in 2009. The package includes a disc of duets and another disc with the Sydney Symphony Orchestra.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Corea embarked on a series of concerts with fellow pianist Herbie Hancock. These concerts were presented in elegant settings with both artists dressed formally and performing on concert grand pianos. The two played each other's compositions, as well as pieces by other composers such as Béla Bartók, and duets. In 1982, Corea performed The Meeting, a live duet with the classical pianist Friedrich Gulda.

In December 2007, Corea recorded a duet album, The Enchantment, with banjoist Béla Fleck.[13] Fleck and Corea toured extensively for the album in 2007. Fleck was nominated in the Best Instrumental Composition category at the 49th Grammy Awards for the track "Spectacle".[14]

In 2008, Corea collaborated with Japanese pianist Hiromi Uehara on the live album Duet (Chick Corea and Hiromi). The duo played a concert at Tokyo's Budokan arena on April 30.[15]

In 2015, he reprised the duet concert series with Hancock, again sticking to a dueling-piano format, though both now integrated synthesizers into their repertoire. The first concert in this series was at the Paramount Theatre in Seattle and included improvisations, compositions by the duo, and standards by other composers.[16]

Later work

Corea's other bands included the Chick Corea Elektric Band, its trio reduction called “Akoustic Band”, Origin, and its trio reduction called the New Trio. Corea signed a record deal with GRP Records in 1986 which led to the release of ten albums between 1986 and 1994, seven with the Elektric Band, two with the Akoustic Band, and a solo album, Expressions.

The Akoustic Band released a self-titled album in 1989 and a live follow-up, Alive, in 1991, both featuring John Patitucci on bass and Dave Weckl on drums. It marked a return to traditional jazz trio instrumentation in Corea's career, and the bulk of his subsequent recordings have featured acoustic piano.[17]

In 1992, Corea started his own label, Stretch Records.[3]

In 2001, the Chick Corea New Trio, with bassist Avishai Cohen and drummer Jeff Ballard, released the album Past, Present & Futures. The eleven-song album includes only one standard (Fats Waller's "Jitterbug Waltz"). The rest of the tunes are Corea originals. He participated in 1998's Like Minds with old associates Gary Burton on vibraphone, Dave Holland on bass, Roy Haynes on drums, and Pat Metheny playing guitars.

During the later part of his career, Corea also explored contemporary classical music. He composed his first piano concerto—an adaptation of his signature piece "Spain" for a full symphony orchestra—and performed it in 1999 with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. In 2004 he composed his first work without keyboards: his String Quartet No. 1 was written for the Orion String Quartet and performed by them at 2004's Summerfest in Wisconsin.

Corea continued recording fusion albums such as To the Stars (2004) and Ultimate Adventure (2006). The latter won the Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Album, Individual or Group.

In 2008, the third version of Return to Forever (Corea, Stanley Clarke, Lenny White, and Di Meola) reunited for a worldwide tour. The reunion received positive reviews from jazz and mainstream publications.[18] Most of the group's studio recordings were re-released on the compilation Return to Forever: The Anthology to coincide with the tour. A concert DVD recorded during their performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival was released in May 2009. He also worked on a collaboration CD with the vocal group The Manhattan Transfer.

A new group, the Five Peace Band, began a world tour in October 2008. The ensemble included John McLaughlin whom Corea had previously worked with in Miles Davis's late 1960s bands, including the group that recorded Davis's classic album Bitches Brew. Joining Corea and McLaughlin were saxophonist Kenny Garrett and bassist Christian McBride. Drummer Vinnie Colaiuta played with the band in Europe and on select North American dates; Brian Blade played all dates in Asia and Australia, and most dates in North America. The vast reach of Corea's music was celebrated in a 2011 retrospective with Corea guesting with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra in the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts; a New York Times reviewer had high praise for the occasion: "Mr. Corea was masterly with the other musicians, absorbing the rhythm and feeding the soloists. It sounded like a band, and Mr. Corea had no need to dominate; his authority was clear without raising volume."[19]

A new band, Chick Corea & The Vigil, featured Corea with bassist Hadrien Feraud, Marcus Gilmore on drums (carrying on from his grandfather, Roy Haynes), saxes, flute, and bass clarinet from Origin vet Tim Garland, and guitarist Charles Altura.

Corea celebrated his 75th birthday in 2016 by playing with more than 20 different groups during a six-week stand at the Blue Note Jazz Club in Greenwich Village, New York City. "I pretty well ignore the numbers that make up 'age'. It seems to be the best way to go. I have always just concentrated on having the most fun I can with the adventure of music."[20]

Personal life

Corea and his first wife Joanie had two children, Thaddeus and Liana; the marriage ended in divorce. In 1972, Corea married his second wife, vocalist/pianist Gayle Moran.[21][22]

In 1968, Corea read Dianetics, author L. Ron Hubbard's most well-known self-help book, and developed an interest in Hubbard's other works in the early 1970s: "I came into contact with L. Ron Hubbard's material in 1968 with Dianetics and it kind of opened my mind up and it got me into seeing that my potential for communication was a lot greater than I thought it was."[23]

Corea said that Scientology became a profound influence on his musical direction in the early 1970s: "I no longer wanted to satisfy myself. I really want to connect with the world and make my music mean something to people."[24] He also introduced his colleague Stanley Clarke to the movement.[25][better source needed] With Clarke[26] Corea played on Space Jazz: The soundtrack of the book Battlefield Earth, a 1982 album to accompany L. Ron Hubbard's novel Battlefield Earth.[27]

Corea was excluded from a concert during the 1993 World Championships in Athletics in Stuttgart, Germany. The concert's organizers excluded him after the state government of Baden-Württemberg had announced it would review its subsidies for events featuring avowed members of Scientology.[28][29] After Corea's complaint against this policy before the administrative court was unsuccessful in 1996,[30] members of the United States Congress, in a letter to the German government, denounced the ban as a violation of Corea's human rights.[31] Corea was not banned from performing in Germany, however, and had several appearances at the government-supported International Jazz Festival in Burghausen; he was awarded a plaque on Burghausen's "Street of Fame" in 2011.[32]

Corea died of a rare form of cancer shortly after his diagnosis. He died at his home near Tampa Bay, Florida, on February 9, 2021, at the age of 79.[2][33][34]

Discography

Awards and honors

Corea's 1968 album Now He Sings, Now He Sobs was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1999. In 1997, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music.[35] In 2010, he was named Doctor Honoris Causa at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).[36]

Grammy Awards

Corea won 27 Grammy Awards and was nominated 71 times for the award.[6]

| Year | Category | Album or song |

|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Best Jazz Performance by a Group | No Mystery (with Return to Forever) |

| 1977 | Best Instrumental Arrangement | "Leprechaun's Dream" |

| 1977 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | The Leprechaun |

| 1979 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | Friends |

| 1980 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | Duet (with Gary Burton) |

| 1982 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | In Concert, Zürich, October 28, 1979 (with Gary Burton) |

| 1989 | Best R&B Instrumental Performance | "Light Years" |

| 1990 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | Chick Corea Akoustic Band |

| 1999 | Best Jazz Instrumental Solo | "Rhumbata" with Gary Burton |

| 2000 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | Like Minds |

| 2001 | Best Instrumental Arrangement | "Spain for Sextet & Orchestra" |

| 2004 | Best Jazz Instrumental Solo | "Matrix" |

| 2007 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | The Ultimate Adventure |

| 2007 | Best Instrumental Arrangement | "Three Ghouls" |

| 2008 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | The New Crystal Silence (with Gary Burton) |

| 2010 | Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Group | Five Peace Band Live |

| 2012 | Best Improvised Jazz Solo | "500 Miles High"[37] |

| 2012 | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Forever |

| 2013 | Best Improvised Jazz Solo | "Hot House" |

| 2013 | Best Instrumental Composition | "Mozart Goes Dancing" |

| 2015 | Best Improvised Jazz Solo | "Fingerprints" |

| 2015 | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Trilogy |

| 2020 | Best Latin Jazz Album | Antidote (with The Spanish Heart Band) |

| 2021 | Best Jazz Instrumental Album | Trilogy 2 (with Christian McBride and Brian Blade) |

| 2021 | Best Improvised Jazz Solo | "All Blues" |

| 2022 | Best Improvised Jazz Solo | "Humpty Dumpty (Set 2)" |

| 2022 | Best Latin Jazz Album | Mirror Mirror |

Latin Grammy Awards

| Year | Award | Album/song |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Best Instrumental Album | The Enchantment (with Béla Fleck) |

| 2011 | Best Instrumental Album | Forever (with Stanley Clarke and Lenny White) |

References

- ^ Yanow, Scott. "Chick Corea". AllMusic. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c Siemaszko, Corky (February 12, 2021). "Jazz Keyboard Virtuoso Chick Corea Dead from Cancer Age 79". NBC.

- ^ a b c d e f Yanow, Scott. "Chick Corea – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "Chick Corea". Blue Note. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Heckman, Don (August 18, 2001). "Playing in His Key". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Artist: Chick Corea". Grammy.com. Recording Academy. 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Today in history". ABC News. Associated Press. June 12, 2014.

- ^ Russonello, Giovanni (February 11, 2021). "Chick Corea, Jazz Keyboardist and Innovator, Dies at 79". The New York Times. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Chick Corea Interview". Marktowns.com.

- ^ "Musica Jazz, Italy – Chick Corea". Chickcorea.com. June 6, 2018.

- ^ "Chick Corea On Piano Jazz". WWNO. January 20, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Chick Corea Interview". Artistinterviews.eu. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Levine, Doug (April 24, 2007). "Chick Corea, Bela Fleck Collaborate On New CD". VOA News. Voice of America. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ "Concord | Independent Music". Concord Entertainment Company. Archived from the original on October 15, 2019. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ "Website undergoing maintenance | NME.com". NME. January 26, 2009. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009.

- ^ de Barros, Paul (March 15, 2015). "Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea prove masters know how to have fun". The Seattle Times. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Chick Corea Akoustic Band. Jazz San Javier 2018". YouTube. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019.

- ^ Chinen, Nate (August 3, 2008). "The Return of Return to Forever". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ Ratliff, Ben (January 23, 2011). "A Jazz Man Returns to His Past". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ "Chick Corea, 75th Birthday Celebration, October 19 thru December 11, 2016," New York: Blue Note

- ^ Zimmerman, Brian (August 21, 2019). "On the road with Chick: A jazz globetrotter shares his favorite spots and travel tips". jazziz.com.

- ^ "Corea, Chick". Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ Corea, Chick (February 13, 2016). "Chick Corea, on The Ultimate Adventure". NPR.org. Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ "[title not cited]". Down Beat. October 21, 1976. p. 47.

I no longer wanted to satisfy myself. I really want to connect with the world and make my music mean something to people.

- ^ Ortega, Tony (c. 2018). "Stanley Clarke, Scientology celebrity". The Underground Bunker (tonyortega.org).

- ^ Ediriwira, Amar (October 4, 2016). "How L. Ron Hubbard made the craziest jazz record ever". The Vinyl Factory. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ Morris, Chris (February 11, 2021). "Chick Corea, jazz fusion pioneer, dies at 79". Variety (obituary). Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Chick Corea". Laut.de. Biographie bei. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Bloch, Werner (January 23, 1999). "Chick Corea: Scientology-Zeuge gegen Deutschland: Ein peinlicher Auftritt in Berlin: Chick Coreas Konzert im Namen von Scientology". Süddeutsche Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on August 24, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ VGH Baden-Württemberg, Urteil vom 15 Oktober 1996, Aktenzeichen 10 S 176/96

- ^ Hennessey, Mike (January 18, 2011). "U.S. lawmakers rip Germany's ban of Corea show". Billboard. Retrieved June 9, 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ Haserer, Wolfgang (January 18, 2011). "Musikalisch unumstritten" (in German). OVB Online. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ Shteamer, Hank (February 11, 2021). "Chick Corea, jazz pianist who expanded the possibilities of the genre, dead at 79". Rolling Stone (obituary). Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ Russonello, Giovanni (February 11, 2021). "Chick Corea, jazz keyboardist and innovator, dies at 79". The New York Times (obituary). Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Chick Corea" (PDF). The Kurland Agency. November 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2018.

- ^ "Chick Corea utnevnt til æresdoktor – NRK Trøndelag – NRK Nyheter". Nrk.no. October 27, 2010. Retrieved July 1, 2011.

- ^ "Indies/And the Nominees Are". Billboard. January 7–21, 2012. pp. 38, 44, 47.

External links

- Official site

- Official discography

- Chick Corea discography at Discogs

- An Interview with Chick Corea by Bob Rosenbaum, July 1974

- Chick Corea talks to Michael J Stewart about his Piano Concerto

- Chick Corea Interview at NAMM Oral History Collection (2016, 2018)

- Chick Corea at IMDb

- 1941 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American keyboardists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American pianists

- 20th-century jazz composers

- 21st-century American keyboardists

- 21st-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American pianists

- 21st-century jazz composers

- American Scientologists

- American jazz composers

- American jazz pianists

- American male jazz composers

- American male jazz pianists

- American people of Italian descent

- People of Sicilian descent

- People of Calabrian descent

- Chick Corea Elektric Band members

- Circle (jazz band) members

- Crossover (music)

- Deaths from cancer in Florida

- ECM Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- GRP All-Star Big Band members

- GRP Records artists

- Jazz fusion pianists

- Jazz musicians from Massachusetts

- Keytarists

- Latin Grammy Award winners

- Miles Davis

- People from Chesterfield, Massachusetts

- Post-bop composers

- Post-bop pianists

- Return to Forever members

- The Jazz Messengers members