Raoul Wallenberg

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. |

Raoul Gustav Wallenberg | |

|---|---|

Wallenberg passport photo from June 1944 | |

| Born | August 4, 1912 |

| Died | presumed July 16, 1947 |

| Occupation | Diplomat |

| Parent(s) | Raoul Oscar Wallenberg Maria "Maj" Sofia Wising |

Raoul Gustav Wallenberg (August 4, 1912 – July 16, 1947?)[1][2][3] was a Swedish humanitarian sent to Budapest, Hungary under diplomatic cover to rescue Jews from the Holocaust.

He worked to save the lives of many Hungarian Jews in the later stages of World War II by issuing them protective passports from the Swedish embassy. These documents identified the bearers as Swedish nationals awaiting repatriation. It is impossible to determine exactly how many Jews were rescued by his actions. Yad Vashem credits him with saving 15,000 lives.[4]

On January 17, 1945, he was arrested on the direct order of Soviet Deputy Commissar for Defense Nikolai Bulganin. It is probable that the order came from Stalin, for reasons never disclosed. In 1957, responding to diplomatic pressure, the Soviets announced that Wallenberg had died of a heart attack in 1947 in Lubyanka prison in Moscow, but this has been disputed.

Early life

He was born in Lidingö (near Stockholm, Sweden) to Raoul Oscar Wallenberg (1888–1912), a Swedish naval officer, and Maria "Maj" Sofia Wising (1891–1979). Raoul Oscar Wallenberg died of cancer three months before his son was born.[5] In 1918, his mother married Fredrik von Dardel, and Raoul had a half-brother, Guy von Dardel[1]. Raoul Wallenberg also had a maternal half-sister, Nina Lagergren. Nina's daughter, Nane Maria Lagergren, married Kofi Annan.[6][3]

In 1931, Wallenberg went to study architecture in the United States at the University of Michigan. In college, he learned to speak English, German and French.[7] He used his vacations to explore America. Although he came from a wealthy family, during his free time, he worked at odd jobs, including a World's Fair.

He returned to Sweden, but he was unable to find a job as an architect. Eventually, his grandfather arranged a job for him in Cape Town, South Africa, in the office of a Swedish company that sold construction material. Between 1935 and 1936, he was employed in a minor position at a branch office of the Holland Bank in Haifa. He returned to Sweden in 1936 and got a job with the help of his uncle, Jacob Wallenberg, at the Central European Trading Company, a trading company with only five employees.[8] The firm was owned by Kálmán Lauer, a Hungarian Jewish emigré. When the outbreak of war barred Lauer from certain areas of Europe, Wallenberg traveled as his representative.[9] Within a year, Wallenberg was a joint owner and the international director of the company.[6]

The Holocaust

Starting in 1938, under the regency of Miklós Horthy, Hungary passed a series of anti-Jewish measures that restricted the professions of Jews, that reduced the number of Jews in government jobs, and that prohibited intermarriage. The first massacre of Hungarian Jews took place in July of 1941, when 20,000 Jews were driven from Carpathian Ruthenia into German-occupied Soviet territory, where they were killed by the German SS.[10]

Hillel Kook (also known as Peter Bergson), his rescue group, the leaders of the World Jewish Congress, and the American Joint Distribution Committee (Joint) incessantly pressured the U.S. government to help rescue Jews from the Nazis and Fascists. These groups had considerable support in both the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives[11] as well as from Secretary of Treasury, Henry Morgenthau, Jr. As the pressure for action mounted and after much delay, United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the War Refugee Board (WRB) to aid civilian victims of the Nazis and the Axis powers in January of 1944. The executive order establishing the board read: "it is the policy of this Government to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war".[12]

On March 23, 1944, the Germans installed a puppet government in Hungary with Döme Sztójay serving as Prime Minister. Miklós Horthy remained as regent, but he had less power than before. The mass deportation of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz began on May 151944, at the rate of 12,000 persons per day.[10] By July 71944, the Germans and their Hungarian henchmen had deported 434,351 Jews. The majority of them had been sent to Auschwitz.[13]

The deportations provoked a storm of international protests, especially after the publication of the Wetzler-Vrba Report, which is also known as the Auschwitz Report, was included as the main section in the Auschwitz Protocol. This report was the written testimonies of two Slovakian refugees from Auschwitz named Rudoph Vrba and Alfred Wetzler. It contained a detailed description of the mass murders committed by the Germans at Auschwitz. The release of this report triggered a major grassroots protest in Switzerland and England, which was supported by about 400 headlines protesting the German barbarism. The Swiss news articles were published in spite of strict Swiss censorship rules. Publication of the report also triggered Sunday sermons in Swiss churches that deep concern about the fate of Jews. A leading Swiss theologian, Paul Vogt, wrote and published a book called Am I My Brother's Keeper?

The intensity and scale of the foreign protests, combined with the efforts of the WRB, led President Roosevelt, the Pope, the King of Sweden and other world leaders to press Horthy to stop the deportations. The pressure, combined with protests from his own family and many moderate Hungarian politicians, such as former Prime Minister Count Stephan Bethlen, and from the major Christian churches, convinced Horthy that he had to act. It became a strategic goal for Horthy and the moderate politicians around him to create goodwill with the winning side by extracting his country from the war and easing the plight of the Jews. Horthy stopped the deportations on July 8,[10] a day before Wallenberg arrived in Budapest, and forced the Sztójay government to ease its political actions directed at the Jews.

The lull gave Wallenberg and the other important preexisting rescue efforts in the city, such as that of the Swiss under the leadership of Carl Lutz, the Vatican’s under Angelo Rotta, the Spanish headed by Giorgio Perlasca and the Portuguese, a stronger position in negotiations with the Hungarian authorities. The discussions dealt mainly with exempting certain categories of Jews – like Christian Jews, those with Palestine certificates or those with a near Swedish, Spanish etc. connection – from the fate of the rest. Even the Jewish Council and the Zionist Youth Underground in Budapest began to negotiate with the Palace. The new politic "put rescue in the air", empowering ordinary citizens to act on behalf of the surviving remnant of Hungary's Jews.[14][15][16]

Raoul Wallenberg's mission

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

Iver Olsen, the War Refugee Board's representative in Scandinavia, and Norbert Masur, the Scandinavian representative to the World Jewish Congress, began searching for someone who could travel to Hungary without great risk and lend the help of these organizations to Hungarian Jews. The best choice would have been a neutral diplomat and both organizations lobbied the Swedish government, but there was no diplomat willing to go.

Raoul Wallenberg was singled out for the task by Olsen and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the predecessor of the CIA) at the suggestion of either Hungarian businessman Kálmán Lauer or shipping magnate Sven Salén. Wallenberg had visited Hungary on at least two occasions, but only for relatively short periods of time, and he spoke no Hungarian. However, there were other factors involved. Lauer lobbied hard for Wallenberg for strong, personal reasons (Wallenberg was to bring Lauer’s relatives to Sweden), but they also had business interests at stake. A close reading of Lauer’s account of Wallenberg’s journey implies that Wallenberg had not concluded his business dealings during his first visit to Budapest in the autumn of 1943. Wallenberg had begun to make preparations to travel to Hungary as early as May 1944, but did not receive the necessary German transit visa at that time. Correspondence between the two men confirms that they had business interests that needed to be attended to in Hungary, interests that coincided with those of Sven Salén. This led to the intervention of Salén, whose support would appear to be the factor that ultimately convinced both the Americans and the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Wallenberg’s suitability for the task. The Swedish Chief Rabbi, Marcus (Mordecai) Ehrenpreis, expressed doubts at first, but in the end, he probably had no choice. The selection was sanctioned by the U.S. minister in Stockholm, Herschel Johnson, who also persuaded the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs to accept Wallenberg for the job. Wallenberg was appointed Secretary to the Legation and was allowed to travel to Hungary.

His immediate task in Budapest was to lend the War Refugee Board's support to the saving of Hungarian Jews. Details of his possible intelligence work are still uncertain, but it was quite likely that this was also part of his brief. (see Redovisning p. 44.) This work was already under way in Budapest when Raoul Wallenberg arrived, both under the auspices of the Swedish Legation and other neutral countries as well as through the agency of the papal nuncio. His arrival heralded an expansion of this activity but also a tightening of the rules surrounding it at the Swedish Legation. The expansion was, in all probability, an emulation of the example set by the Swiss, for whom every Palestine Certificate was regarded as a “family document”: it is likely that this was an initiative of Jewish individuals who were already issuing Swedish provisional passports at the Swedish Legation. The Hungarian authorities had limited these to a maximum of 4,500, presumably after they had approved the Swedes’ definition of 649 Swedish entry visas approved by the Swedish Foreign Office as “family visas”, with a corresponding increase in the number of protective documents.

It soon became well known that Wallenberg had substantial financial backing. First and foremost, this was revealed by the way he succeeded in tapping local Jewish funds. He had credit and could acquire considerable sums of money or quantities of goods against the promise that the money would be repaid into Swiss bank accounts. To a very great degree, Wallenberg’s influence hinged on the implicit knowledge of his background.[citation needed] He had been sent to Budapest at the behest of the WRB, but with the active involvement of the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. He had Swedish diplomatic status, answering initially to the First Secretary of the Legation, Per Anger, but receiving his instructions directly from the WRB. He was given a long list of people to contact, and was directed to organize a network to protect Jews and to prepare escape routes from Budapest. Wallenberg contacted some of the names of the list – along with others who did not figure there – and presumably was even allowed access on one occasion to Miklós Horthy, Jr., the son of the Hungarian regent. Apart from this, however, there is no documentary evidence that he became involved in the development and coordination of the general rescue efforts in Budapest, or that he collaborated with or assisted the resistance. On the contrary, it was he who was assisted both by the government and by the resistance in order to protect his wards.[citation needed]

As a newcomer, Wallenberg lacked the extensive network of contacts and influence, especially in high political circles, of the papal nuncio, other diplomats from neutral powers, and individuals, such as Valdemar Langlet, who were already involved in the rescue effort. All the documents attest that throughout the entire time the Horthy regime held power the Swedish Envoy, Ivan Danielsson, and First Secretary Per Anger handled all contacts with the government. Also, there was no immediate change when the used substantial amounts of money that Wallenberg had at his disposal to extend his circle of acquaintances and influence. His reports and diaries reveal that he spent relatively heavily on wining and dining, as well as other forms of entertaining. It is likely that he received much support from the group of influential Jews headed by Hugo Wohl who had congregated at the Swedish Legation.

Hungarian society was divided on the issue of the Jews and there was a deep schism between the leadership in Hungary and Germany. The Hungarian aristocrats, or the “aristocratic” bourgeoisie, and a portion of the middle class never approved of the German Nazis’ political populism and its brutal “Judenpolitik”, and many of them refused to be a part of it. The Nazis were always obliged to rely upon their like-minded Hungarian henchmen. At the same time, the Germans realized that these kindred spirits were incapable of governing the country and that Germany could ill afford to dispatch an occupation force large enough to enforce its wishes. Therefore, the elderly Horthy was permitted to remain at his post and retain some semblance of autonomy.

This encouraged anti-German elements to support and to a certain degree, even work with the Jews. Moreover, when Horthy stopped the deportations, even some of the Hungarian politicians who previously had been either indifferent or hostile to the Jews began to adopt a more helpful attitude to the rescue operations of the International Red Cross (IRC) and the neutral legations. The Hungarian authorities not only gave their consent, but also on occasion actively encouraged the Swedish Legation to extend its protection to more Jews. They had even begun to recognize temporary passports even before Wallenberg arrived, and they were prepared to issue certificates to holders of such passports attesting to this. They also indicated which types of documents they would accept as foreign identity and travel papers. Everything suggests that it was the negotiations between the Hungarian authorities and the Jews at the Swedish Legation that led to the creation of Sweden's famous, blue-and-yellow “protective passports”, which made foreigners of thousands of Jews with Hungarian citizenship. However, the passport requirements were such that it was almost exclusively the well-to-do who qualified.

The favorable Hungarian attitude was compounded by Germany's increasing dependence on Sweden's continued neutrality from August 1944 onwards, enhancing Sweden's bargaining position. The situation was propitious for the Swedish attempt to exempt certain categories of Jews from the fate of so many of their fellow countrymen. Little effort was required to help well-to-do Jews in Budapest obtain protective passports, a task which, to a great extent, was managed by the Jewish volunteers “employed” in the humanitarian section of the Swedish Legation.

Even after the Fascist Szálasi government took power on October 15 1944, the change in attitude was less abrupt than it first appeared. The new regime was prepared to accept the same numbers of protective passports under the same conditions as the previous government in exchange for political recognition from the governments of the states issuing these documents. Raoul Wallenberg’s good relations with Foreign Minister Kemény paved the way for face-to-face negotiations with him; the result was that, for the first time, it was the Swedish “wards” who were most favoured. However, the early discussions that were held directly between Szálasi and the papal nuncio and representatives of the other neutral legations ensured that all foreign papers were soon recognized by the Arrow Cross Party government. At the very highest level, it was still the papal nuncio and IRC representative Fredrik Born who exercised the greatest influence. It was their personal interventions that had the greatest effect on Szálasi and that saw that relatively favourable conditions were restored. On November 17, Szálasi issued an order that all Jews with foreign documents should be handed over to the appropriate legation.

Wallenberg’s role began to assume greater importance after October 15, but everything suggests that he continued to use his influence and his access to money primarily to protect those in possession of Swedish papers. This is the case in both instances where documentary sources attest to his direct intervention to save Jews. However, Wallenberg did not risk coming into conflict with the Hungarian authorities, nor did he contravene the rules that had been laid down. In both cases, he first applied for permission and received approval both from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs and the other authorities involved. He even received official assistance from the authorities to carry out these rescue actions for as long as the Szálasi government continued to hope for Swedish recognition. The entire Swedish effort depended on the support of the Hungarian government – and, after October 15 1944, that of the “Leader of the Nation”, Szálasi. It would have been extremely imprudent to risk forfeiting the collaboration by conducting illicit actions that could be traced back to the Swedish Legation. Even Per Anger concedes this towards the end of his book, when he writes about the number of protective passports issued, despite the fact that he contradicts himself on the very same page and gives the wrong number of approved passports:

“We had an agreement with the Szálasi government for the approval of 5,000 such passports. Of course, things did not stop there. Many times this number of passports were being issued in secret all the time, albeit limited to individuals who could prove that they had some kind of connection with Sweden. If we had succumbed to the temptation to issue passports to everyone from the ranks of the Jewish population, the papers would most certainly have lost their value. Moreover, it would not have taken long for the Nazis to understand that we were sabotaging the agreement we had reached with them about limiting numbers, and they would have seen to it that we could no longer be of help to anyone … Wallenberg was as aware as we were that no one must jeopardize the legation’s existence” (Per Anger, Med Raoul Wallenberg i Budapest, p. 151)

The situation deteriorated at the beginning of December when the Hungarian government realized that the agreement were being flouted by the Swedes and gave up hope of a Swedish recognition. This did not, however, herald any radical change for the Swedish legation and the Jews under its protection until the government left Budapest. When that happened, respect for Swedish diplomatic immunity evaporated, and the Swedish Legation was occupied by Arrow Cross forces.

There are no documented rescue actions after the opportunities for legal intervention were exhausted. Wallenberg himself gave up hope of being able to do anything once the Swedish Legation had been occupied. The rescue actions were not revived until one of Wallenberg’s assistants, Károly Szabó, managed to contact the moderate Arrow Cross leader, Pál Szalai. However, even that did not always help. Despite Szalai’s assistance, the attacks against the “Swedish” houses and the terrorization of Jews nominally under the protection of the Swedes continued. Hundreds of Jews were executed in late December 1944 and early January 1945 by Arrow Cross mobs that by then were running out of control. The terror these mobs spread was not stilled until the Russians took control of the city – and then was only replaced by the terror inflicted by the Red Army over the entire population.

A part of the Wallenberg-myth is that he met and negotiated with both Horthy and the notorious Adolf Eichmann. It is highly improbable that this ever happened. There are no documents whatsoever about these meetings and almost all the professional historians who dealt with the Wallenberg story (see Attila Lajos, Karsai László, Berndt Shiller, etc.) or writers (Ember Mária) agree that these meetings never took place. The Germans had nothing to do with the protective documents, because the handling of the Jewish question was in the hands of the Hungarian authorities after Horthy stopped the deportation and they agreed to respect that. Eichmann had no authority to negotiate about the passports, buildings or other official matters with Wallenberg. These were under Hungarian control and authority. The high level negotiations’ between the Hungarian government and the Swedish legation were done exclusively by Danielsson or Per Anger.

Wallenberg soon became a hated person in the eyes of many Arrow Cross members, but as long as the government remained in Budapest, they didn’t dare harm him. But after the government left Budapest and the Swedish legation was occupied, Wallenberg was forced to hide. He started sleeping in a different house each night to avoid being captured or possibly killed.[17]

The last people to see Wallenberg in Budapest were Ottó Fleischmann, Károly Szabó, and Pál Szalai, who were invited to a supper at the Swedish Embassy building in Gyopár street on January 12, 1945.[18] The next day, Wallenberg contacted the Russians to secure food and supplies for the people under his protection.[19] He and his driver, Vilmos Langfelder (1912-1948), were detained by the Soviet Red Army on January 17, 1945, when they captured Budapest, on suspicion of being a spy for the United States, since the War Refugee Board was actually engaged in espionage.[20][21][22] He was driven to the headquarters of Rodion Malinovsky in Debrecen by the NKVD. Wallenberg's last recorded words were: "I'm going to Malinovsky's ... whether as a guest or prisoner I do not know yet."[23] In 2003, a review of wartime Soviet correspondences, indicated Vilmos Böhm may have provided Wallenberg's name to Stalin as a person to detain.[24]

Wallenberg said that he had 7000 people under his care when he contacted the Russians on January 13. This is documented by a hand written note on the margin of an order issued by the Russian officer Kuprijanov, on January 14 1945. The final report of Wallenberg's main assistant, Hugo Wohl, shows a little less than 7000 under Swedish protection. (The Russian document is cited in the Swedish-Russian workgroup's report in 2000; Wohl's report in Lévai, 1988, s. 252-255) Among those saved by Wallenberg were the biochemist Lars Ernster, who was housed in the Swedish embassy, and Andor Szentivanyi who discovered The Beta Adrenergic Theory of Asthma and Tom Lantos, later a member of the United States House of Representatives, who lived in one of the Swedish protective houses.[25]

Wallenberg did not work alone in Budapest; at the height of his program, over 350 people were involved.[26] Sister Sara Salkahazi was caught sheltering Jewish women and was killed by members of the Arrow Cross Party. Carl Lutz, a Swiss diplomat, also issued protective passports from the Swiss embassy, and was the initiator of the rescue operation in spring 1944. Italian businessman Giorgio Perlasca posed as a Spanish diplomat and issued forged visas. Henryk Sławik was a Polish diplomat who distributed fake passports.

Moscow

Information about Wallenberg’s fate after his detention by the Russians is mostly speculative. There were many more or less reliable witnesses who allegedly met him during his imprisonment.

Wallenberg was transported by train from Debrecen through Romania to Moscow.[22]. The Soviets may have moved him to their capital in hopes of exchanging him for defectors in Sweden.[27] Vladimir Dekanosov notified the Swedes on January 16, 1945 that Wallenberg was under the protection of Soviet authorities. On January 21, 1945, Wallenberg was transferred to Lubyanka prison and put in cell 123, with fellow prisoner, Gustav Richter, a police attaché at the German embassy in Romania. Richter testified in Sweden in 1955 that Wallenberg was interrogated once for about an hour and a half, in early February of 1945. On March 1, 1945, Richter was moved from his cell and never saw Wallenberg again.[28][19]

On March 8, 1945, Soviet-controlled Hungarian radio announced that Wallenberg and his driver had been murdered on their way to Debrecen, suggesting that they were killed by the Arrow Cross Party or the Gestapo. Sweden's foreign minister, Östen Undén, and ambassador to the Soviet Union, Staffan Söderblom, wrongly assumed that they were dead.[6] In April of 1945, William Averell Harriman of the U.S. State Department, offered the Swedish government help in inquiring about Wallenberg’s fate, but the offer was declined.[7] Söderblom met with Molotov and Stalin in Moscow on June 15, 1946. Söderblom, believing Wallenberg was dead, ignored talk of an exchange for Russian defectors in Sweden.[29][30]

In February of 1949, former German Colonel Theodor von Dufving, as a prisoner of war, provided evidentiary statements concerning Wallenberg. While en route to Vorkuta, in the transit camp in Kirov, Dufving encountered a prisoner with his own special guard and dressed in civilian clothes. The prisoner claimed that he was a Swedish diplomat and that he was there "through a great error."

On February 6, 1957, the Soviets released a document found in their archives which stated that "I report that the prisoner Walenberg [sic] who is well-known to you, died suddenly in his cell this night, probably as a result of a heart attack. Pursuant to the instructions given by you that I personally have Walenberg [sic] under my care, I request approval to make an autopsy with a view to establishing cause of death... I have personally notified the minister and it has been ordered that the body be cremated without autopsy." The document was dated July 17, 1947, and was signed by Smoltsov, then the head of the Lubyanka prison infirmary. It was addressed to Viktor Semyonovich Abakumov, the Soviet minister of state security.[19][2] In 1989, the Soviets returned Wallenberg's personal belongings to his family, including his passport and cigarette case. Soviet officials said they found the materials when they were upgrading the shelves in a store room.[31][32]

A Swedish-Russian working group, after Guy von Dardel's, Raoul Wallenberg's half-brother, initiative [2] was set up in 1991 to search 11 separate military and government archives from the former Soviet Union for information about Wallenberg.[22][33][34] In Stockholm in 2000, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev announced that Wallenberg had been executed in 1947 in Lubyanka prison. He claimed that Vladimir Kryuchkov, the former Soviet secret police chief, told him about the shooting in a private conversation. The statement did not explain why Wallenberg was killed or why the government had lied about it.[20][35] Pavel Sudoplatov claimed that Raoul Wallenberg was poisoned by Grigory Mairanovsky.[36] In 2000, Russian prosecutor Vladimir Ustinov signed a verdict posthumously rehabilitating Wallenberg and his driver, Langfelder, as "victims of political repression".[37] A number of files pertinent to Wallenberg were turned over to the chief rabbi of Russia by the Russian government in September 2007.[38] They will be housed at the Museum of Tolerance in Moscow, scheduled to open on 2008.

Because of the deliberate destruction of documents by the Soviets, the reason for the arrest and death of Wallenberg may never be known. There is a parallel to his fate in the arrest of two Swiss diplomats detained in Budapest, whose records still exist. Stalin directly ordered the arrest of Maximilian Jaeger and Harald Feller of the Swiss embassy. They were interrogated by SMERSH and were released in exchange for two Russian pilots who had defected to Switzerland.[22]

Several former prisoners have claimed that Wallenberg may still have been alive into the early 1950s.[39] The last reported sightings of Wallenberg were by two independent witnesses who said they had evidence that he was in a prison in November of 1987.[40]

Raoul Wallenberg's brother, Professor Guy von Dardel[41], a well known physicist, retired from CERN, is dedicated to finding out his brother's fate.[42] He traveled to the Soviet Union about fifty times for discussions and research, including an examination of the Vladmir prison records.[43] He, his sister Nina Lagergren (Kofi Annan's mother-in-law) and their mother never gave up hope of finding Raoul Wallenberg. Many, including Professor von Dardel and his daughters Louise and Marie, do not accept the various versions of Wallenberg's death and continue to request that the archives in Russia, Sweden and Hungary be opened to impartial researchers.[44] It is assumed that an independent international board of inquiry is required to resolve Raoul Wallenberg's fate. In the family today, Wallenberg's niece, Ms. Louise von Dardel, is the main activist and dedicates much of her time speaking about Wallenberg and to lobbying various countries to help uncover information about her uncle.[44]

Wallenberg show trial preparations 1953 in Hungary

The State Protection Authority (Hungarian: Államvédelmi Hatóság or ÁVH) was the state police force of Hungary from 1945 until 1956. ÁVH actions were not subject to judicial review. On 1953-04-07, early in the morning, Miksa Domonkos, one of the leaders of the Jewish community in Budapest was kidnapped by ÁVH officials to extract "confessions".[45] Preparations for a show trial started in Budapest in 1953 to prove that Wallenberg had not been dragged off in 1945 to the Soviet Union, but was the victim of cosmopolitan Zionists. For the purposes of this show trial, two more Jewish leaders – László Benedek and Lajos Stöckler – as well as two would-be "eyewitnesses" – Pál Szalai and Károly Szabó – were arrested and interrogated using torture.

Károly Szabó was captured on the street on 1953-04-08 and arrested without any legal procedure. His family had no news of him throughout the following six months. A secret trial was conducted against him of which no official record is available to date. After six months of interrogation, the defendants were driven to despair and exhaustion.

The idea that the "murderers of Wallenberg" were Budapest Zionists was primarily supported by Hungarian Communist leader Ernő Gerő, which is shown by a note sent by him to First Secretary Mátyás Rákosi.[46] The show trial was then initiated in Moscow, following Stalin's anti-Zionist campaign. After the death of Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria, the preparations for the trial were stopped and the arrested persons were released. Miksa Domonkos spent a week in hospital and died at home shortly afterwards, mainly due to the torture to which he had been subjected.[45][47].

Legacy

Honors

- In 1966, Wallenberg was honored at Israel's Yad Vashem memorial as one of the Righteous Among the Nations, recognizing non-Jews who saved Jews from the Holocaust.[48]

- He was made an Honorary Citizen of the United States in 1981. When President Ronald Reagan signed the legislation in October 1981, Wallenberg became the second person to be granted this status, after Winston Churchill.[49] Wallenberg became the first Honorary Citizen of Canada in 1985;[50] he was awarded honorary citizenship in Israel in 1986, and in the city of Budapest in 2003.

- January 17, the day he disappeared, was declared Raoul Wallenberg Day in Canada.[51]

- The United States Postal Service issued a stamp to honor him in 1997. Representative Tom Lantos, one of those saved by Wallenberg's actions, said: "It is most appropriate that we honor [him] with a U.S. stamp. In this age devoid of heroes, Wallenberg is the archetype of a hero -- one who risked his life day in and day out, to save the lives of tens of thousands of people he did not know whose religion he did not share."[52]

- The Raoul Wallenberg Committee of the United States bestows the Raoul Wallenberg Award "on individuals, organizations and communities that reflect Raoul Wallenberg's humanitarian spirit, personal courage and nonviolent action in the face of enormous odds."[53]

- The Wallenberg Endowment at the University of Michigan awards the Wallenberg Medal and Lecture to outstanding humanitarians. The university's Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning also awards Wallenberg Scholarships to exceptional undergraduate and graduate students, many of which are given to enable students to broaden their study of architecture to include work in distant locations.[54]

- Groups in the USA, Israel, China and Hungary have been holding International Rescuer Day events on January 17 for the past few years. This is the anniversary of Wallenberg's abduction.[55]

- During the 1980s, Wallenberg had his own entry ("Most Lives Saved") in the Guinness Book of World Records.

- The musical Another Kind of Hero, composed by E.A. Alexander with collaborator Lezley Steele, was performed at the Walnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia in 1992, and in Toronto and New York in 1993. (music clips)

- The portion of 15th Street, SW, in Washington, D.C., on which the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum sits, was renamed Raoul Wallenberg Place.

- Raoul Wallenberg Traditional High School is named after him.

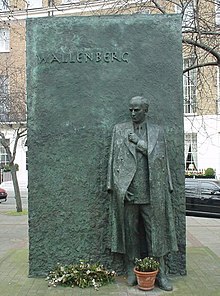

Memorials

- In 2001, a memorial was created in Stockholm to honour Wallenberg. It was unveiled by King Carl XVI Gustaf, at a ceremony attended by the UN Secretary General at the time Kofi Annan and his wife, Wallenberg's niece. It is an abstract memorial depicting people rising from the concrete, accompanied by a bronze replica of Wallenberg's signature. It generated criticism in Sweden because many saw it as ugly and unworthy of such a great hero; however, Wallenberg's sister Nina Lagergren approved of it. At the unveiling, King Carl XVI Gustaf said Wallenberg is "a great example to those of us who want to live as fellow humans." Kofi Annan praised him as "an inspiration for all of us to act when we can and to have the courage to help those who are suffering and in need of help."[56]

- There are a number of sites honoring Wallenberg in Budapest, among them Raoul Wallenberg Memorial Park, which commemorates those who saved many of the city's Jews from deportation to extermination camps, and the building that housed the Swedish Embassy in 1945.[57]

- The Raoul Wallenberg Monument is located on Raoul Wallenberg Walk in Manhattan, across from the headquarters of the United Nations. It was commissioned by the Swedish consulate and was designed by Swedish sculptor Gustav Graitz. Graitz’s piece, Hope, is a replica of Wallenberg’s briefcase, a sphere, five pillars of black granite, and paving stones which once were used on the streets of the Jewish ghetto in Budapest.[58]

See also

References

- ^ The date of death is based on a letter turned over to his family by the Soviets in 1957 and is disputed by some.

- ^ a b German's Death Listed; Soviet Notifies the Red Cross Diplomat Died in Prison.; New York Times; February 15, 1957; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ a b "Raoul Wallenberg". Notable Names Database. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ "Yad Vashem database". Yad Vashem. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

who saved the lives of tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest during World War II ... and put some 15,000 Jews into 32 safe houses.

- ^ Raoul Gustav Wallenberg's paternal grandfather, Gustaf Oscar Wallenberg (1863–1937), the son of Oscar Wallenberg, was a diplomat, an envoy to Tokyo, Constantinople, and Sofia. For a brief biography, see sv:Gustaf Oscar Wallenberg

- ^ a b c "Raoul Wallenberg". Jewish Virtual Library. 2007.

- ^ a b Schreiber, Penny. "The Wallenberg Story". Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ The company name is sometimes translated as the Mid-European Trading Company.

- ^ Lester, Elenore and Werbell, Frederick E.; The Last Hero of Holocaust. The Search for Sweden's Raoul Wallenberg.; New York Times Magazine; March 30, 1980, Sunday; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ a b c "Jewish History of Hungary". Retrieved 2007-02-16.

- ^ Books by Prof. David Wyman and Dr. Rafael Medoff

- ^ "Executive Order Creating the War Refugee Board". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2007-02-16.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Stak Tamás, Hungary’s Human Losses in World War II

- ^ Attila Lajos, 2004

- ^ Jenö Lévai, Zsidósors Európában

- ^ David Kranzler, The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz

- ^ "Final Report of the War Refugee Board from Sweden". Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ József Szekeres: Saving the Ghettos of Budapest in January 1945, Pál Szalai "the Hungarian Schindler" ISBN 9637323147X, Budapest 1997, Publisher: Budapest Archives, Page 74

- ^ a b c Rachel Oestreicher Bernheim (1981). "A Hero for our Time". Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ a b LaFraniere, Sharon; Moscow Admits Wallenberg Died In Prison in 1947. Washington Post; December 23, 2000

- ^ Jews in Hungary Helped by Swede. New York Times; April 26, 1945, Thursday; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ a b c d "Report of Swedish Russian Working Group" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ^ Well Taken Care Of. Time (magazine); Monday, February 18, 1957; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ Soviet double agent may have betrayed Wallenberg; Reuters; May 12, 2003; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ "Lantos's list". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2007-02-15.

Born in Hungary in 1928 to assimilated Jewish parents, he escaped from a forced-labor brigade, joined the resistance and was eventually, with his later-to-be-wife Annette, among the tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews rescued by the Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg.

- ^ "Wallenberg Legacy". Raoul Wallenberg International Movement for Humanity. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ Wallenberg fate shrouded in mystery; CNN; January 12, 2001; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ "Raoul Wallenberg, Life and Work". New York Times. September 6, 1991.

The K.G.B. promised today that it would let agents break their vow of silence to help investigate the fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish diplomat who vanished after being arrested by the Soviets in 1945.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The Last Word on Wallenberg? New Investigations, New Question". Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ "Stuck in Neutral: The Reasons behind Sweden's passivity in the Raoul Wallenberg case" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ Soviets Give Kin Wallenberg Papers. New York Times; October 17, 1989; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ "Raoul Wallenberg, Life and Work". Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ Missing in Action: Raoul Wallenberg; Jerusalem Post

- ^ Excerpt from 1993 working group session

- ^ Cause of Death Conceded. Time (magazine); Monday, August 7, 2000

- ^ Vadim J. Birstein. The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story of Soviet Science. (p.138) Westview Press (2004) ISBN 0-813-34280-5

- ^ Russia: Wallenberg wrongfully jailed; CNN; December 22, 2000; Retrieved on February 14, 2007

- ^ http://www.jta.org/cgi-bin/iowa/breaking/104393.html accessed 29 September 2007

- ^ Search for Swedish Holocaust hero; BBC; Monday, 17 January, 2005

- ^ "Soviets Open Prisons and Records To Inquiry on Wallenberg's Fate". New York Times. August 28, 1990.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Actions done by Raoul Wallenberg's brother, Guy von Dardel

- ^ List of von Dardel's actions

- ^ http://www.arikaplan.com/speech/wallenberg.pdf

- ^ a b Ms. Louise von Dardel's February 2005 talks in the Knesset and the Jerusalem Begin Center and her interviews at the time to Israel TV English news, Jerusalem Post, VESTY (Russian) and Makor Rishon (Hebrew). Also, numerous conversations with Ms. Louise von Dardel

- ^ a b Interview with István Domonkos, son of Miksa Domonkos, who died after the show trial preparations Template:Hu icon

- ^ Kenedi János: Egy kiállítás hiányzó képei Template:Hu icon

- ^ Hungarian Quarterly Template:Hu icon

- ^ "Visiting Yad Vashem: Raoul Wallenberg". Yad Vashem. 2004.

- ^ "Status Report on the Wallenberg Case". Congressional Human Rights Caucus. 2000.

- ^ "Government of Canada Honours Canadian Honorary Citizen Raoul Wallenberg". Canada. 2007.

- ^ "A Tribute to Raoul Wallenberg". Retrieved 2007-02-13.

- ^ "Holocaust Hero Honored on Postage Stamp". United States Postal Service. 1996.

- ^ "The Raoul Wallenberg Committee of the United States". The Raoul Wallenberg Committee of the United States. 2007.

- ^ "Wallenberg Medal and Lecture". The Wallenberg Endowment. 2007.

- ^ http://www.geocities.com/jerusalem_working_group

- ^ "Tributes in United Kingdom". International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ "Tributes in Hungary". Retrieved 2007-02-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ "Raoul Wallenberg Playground". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Related books and sources for research

Archives

Sweden

Riksarkivet, Stockholm UD:s arkiv, 1920 års dossiersystem, HP 21 Eu (Ungern), Politiska ärenden, Ärenden rörande minoriteter. Raoul Wallenberg-arkivet. All the volumes. Raoul Wallenbergföreningens arkiv. All the volumes.

Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek

Uppsala Universitetets arkiv, Raoul Wallenberg-projektets arkiv. Intervju F2C001-F2C319; F2C320-F2C503 med överlevande från Budapest (on microfilm).

Hungary

Magyar Országos Levéltár (MOL), Budapest

Open Society Archives (OSA Archivum), Budapest Thematic Guide and direct access to digitized documents

Külügyminisztérium (Foreign Ministry)

KÜM, K 101, Stockholmi követség, 1917 – 1947. 13 cs. 6 tétel: Politikai vonatkozásu ügyek 1920 – 1944. KÜM K 63 413 cs. 1944 – 43 tétel; A Külügyminisztérium politikai osztályának iratai –Nemzetközi zsidokérdés KÜM K 63 100 cs. 1944 – 43 tétel; A Külügyminisztérium politikai osztályának iratai – Zsidó ügyek KÜM K 707 2 cs. 4,5 tétel 1944 – 45 A Nyilas Külügyminisztérium iratai. KÜM K 71 138 cs. II/6, Nemzetközi Vöröskereszt KÜM K 71 139 cs. II/6, Nemzetközi Vöröskereszt

Belügyminisztérium (Ministry of the interior)

BM K 150 4517 cs. XXI tétel, 1944 –45, A belügyminisztérium iratai BM K 150 4517 cs. XXI tétel, Általános iratok

Vöröszkereszt (Red Cross)

P 1577 1 cs. A svéd vöröskerszt gazdasági hivatalának iratai.

Books containing documents

- Braham, Randoph L., The Destruction of Hungarian Jewry, 3 vol., New York 1963 (documents from German archives)

- Benoschofsky, Ilona & Karsai, Elek, Vádirat a nácizmus ellen, 3 vol., Budapest 1967 (documents from Hungarian archives)

- Nylander, Gert & Perlinge, Anders, Raoul Wallenberg in documents 1927 – 1947, Stockholm, 2000 (documents from the Wallenberg bank, the SEB:s archives)

- Raoul Wallenberg: [Handlingar i UD:s arkiv om Raoul Wallenberg], 7 vol., Stockholm 1980

- Räddningen. De svenska hjälpinsatserna. Rapporter ur UD:s arkiv, Stockholm 1997

- Svensk utrikespolitik under andra världskriget. Stadsrådstal, riksdagsdebatter och kommunikéer. Skrifter utgivna av Utrikespolitiska institutet, Stockholm 1946

- Wallenberg, Raoul, Letters and dispatches, 1924 – 1944, New York 1995

- Wahlbäck, Krister & Boberg, Göran, Sveriges sak är vår. Svensk utrikespolitik 1939 – 1945 i dokument, Stockholm 1967

- Älskade farfar, (brevväxlingen mellan Raoul och Gustav Wallenberg utgiven och kommenterade av Gustaf Söderlund och Gitte Wallenberg), Stockholm 1987

Books written by eye wittnesses

- Anger, Per, Med Raoul Wallenberg i Budapest, Stockholm 1985

- Berg, Lars, Vad hände i Budapest?, Stockholm 1949

- Berg, Lars, Boken som försvann, Stockholm 1981

- Langlet, Nina, Kaos i Budapest, Vällingby 1982

- Langlet, Valdemar, Verk och dagar i Budapest, Stockholm 1949

- Lévai, Jenö, A pesti ghetto csodálatos megmentése, Budapest 1946

- Lévai, Jenö, Eichmann in Hungary, Budapest 1961

- Lévai, Jenö, Zsidósors Magyarországon, Budapest 1948

- Lévai Jenö, Raoul Wallenberg, Budapest 1948

- Lévai Jenö, Raoul Wallenberg. Hjälten i Budapest, Stockholm 1948

- Lévai Jenö, Raoul Wallenberg, Budapest 1988

- Lévai Jenö, Raoul Wallenberg - hjälten i Budapest, Stockholm 1948

- Lévai , Jenö, Szürke könyv, Officina, utan år (förmodligen 1946)

- Lévai, Jenö, Fekete könyv, Budapest 1947

- Lévai, Jenö, Black book on the martyrdom of the Hungarian Jewry, Zürich 1948

- Lévai, Jenö, Fehér könyv, Budapest 1946

- Munkácsi, Ernö, Hogyan történt?, Budapest 1947

- Petö, László, Det ändlösa tåget, Arboga, 1984

Books

- Lajos Attila, Raoul Wallenberg. Mítosz és valóság, Budapest 2007

- Lajos, Attila, Hjälten och offren. Raoul Wallenberg och judarna i Budapest, Växjö, Sweden, 2004

- UD informerar: Raoul Wallenberg, Stockholm 1987

- Raoul Wallenberg, Svenska institutet, 1988

- Raoul Wallenberg. Redovisning av den svensk-ryska arbetsgruppen, Stockholm 2000

- Karsai László, ”Ùjabb Wallenberg–dokumentumok” (Nya Wallenbergdokument), Világosság, 1992/12

- Ember Mária, Ránk akarták kenni, Budapest 1992

- Ember Mária, Wallenberg Budapesten, Budapest 2000

- Ett utrikespolitiskt misslyckande. Fallet Raoul Wallenberg och den utrikespolitiska ledningen, SOU 2003: 18, Stockholm 2003

- Carlbäck-Isotalo, Helene, ”Arkivdokument kontra fria fantasier: Wallenberg-fallet färdigdiskuterat?” Historisk Tidskrift, 1994 (114) s. 634 – 636.

- Carlbäck-Isotalo, Helene, “Glasnost and the opening of Soviet archives: time to conclude the Raoul Wallenberg case?” Scandinavian Journal of History, 1992 (17) s. 175 – 207.

- Braham, Randolph L., The Politcs of Genocide, New York 1994

- David Kranzler, The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz: George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland's Finest Hour, Forward by Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, Syracuse University Press (March 2001), ISBN 978-0815628736

- Jenö Lévai, Zsidósors Európában (published in 1948 in Hungarian, about George Mantello and the major Swiss grass roots protests against the Holocaust)

- Larry Jarvik, Who Shall Live and Who Shall Die (video documentary)

- Rapaport, Louis. Shake Heaven & Earth: Peter Bergson and the Struggle to Rescue the Jews of Europe. Gefen Publishing House, Ltd., 1999.

- Raoul Wallenberg, Letters and Dispatches, 1924-1944, Arcade Publishing Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 1-55970-257-3. Portions published in Sweden as, Alskade farfar! [Dearest Grandfather] by Bonniers Foerlag, Sweden

- Berger, Susanne[3] (2005) "Stuck in Neutral: The Reasons behind Sweden's Passivity in the Raoul Wallenberg Case." [4]

External links

- International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation

- The Raoul Wallenberg Committee of the United States

- Wallenberg case chronology

- Raoul Wallenberg bibliography

- Documents to January 8. 1945. [5]

- Wallenberg: More Twists to the Tale, Mária Ember, They Wanted to Blame Us

- Interview with István Domonkos, son of Miksa Domonkos who died after the show trial preparations (Hungarian)

- Search for Raoul Wallenberg

- Raoul Wallenberg memorial in Budapest, Hungary

- Online access to documents from the Open Society Archives (OSA Archivum)

- Raoul Wallenberg in Second Life

- Articles needing cleanup from June 2007

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from June 2007

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from June 2007

- 1912 births

- Disappeared people

- Humanitarians

- Jewish Hungarian history

- Righteous Among the Nations

- University of Michigan alumni

- People from Stockholm

- Swedish diplomats

- Raoul Wallenberg Award recipients

- Swedish people of World War II