Cattle

It has been suggested that Finching (cattle) be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2007. |

| Cattle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Friesian/Holstein cow | |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. taurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bos taurus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

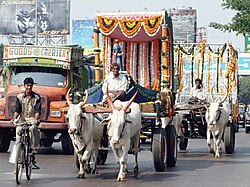

Cattle, colloquially referred to as cows (though technically cow refers only to female bovines), are domesticated ungulates, a member of the subfamily Bovinae of the family Bovidae. They are raised as livestock for meat (called beef and veal), dairy products (milk), leather and as draught animals (pulling carts, plows and the like). In some countries, such as India, they are honored in religious ceremonies and revered. It is estimated that there are 1.3 billion head of cattle in the world today.[1]

Species of cattle

Cattle were originally identified by Carolus Linnaeus as three separate species. These were Bos taurus, the European cattle, including similar types from Africa and Asia; Bos indicus, the zebu; and the extinct Bos primigenius, the aurochs. The aurochs is ancestral to both zebu and European cattle. More recently[verification needed] these three have increasingly been grouped as one species, with Bos primigenius taurus, Bos primigenius indicus and Bos primigenius primigenius as the subspecies.

Complicating the matter is the ability of cattle to interbreed with other closely related species. Hybrid individuals and even breeds exist, not only between European cattle and zebu but also with yaks (called a dzo), banteng, gaur, and bison ("cattalo"), a cross-genera hybrid. For example, genetic testing of the Dwarf Lulu breed, the only humpless "Bos taurus-type" cattle in Nepal, found them to be a mix of European cattle, zebu and yak.[2] Cattle cannot successfully be bred with water buffalo or African buffalo.

The aurochs was originally spread throughout Europe, North Africa, and much of Asia. In historical times, their range was restricted to Europe, and the last animals were killed by poachers in Masovia, Poland, in 1627. Breeders have attempted to recreate cattle of similar appearance to aurochs by careful crossing of domesticated cattle breeds, creating the Heck cattle breed. (See aurochs and zebu articles for more information.) Cows like to say moo lots!!!!!!!!

Terminology

Word origin

Cattle did not originate as a name for bovine animals. It derives from the Latin caput, head, and originally meant movable property, especially livestock of any kind.[3] The word is closely related to "chattel" (a unit of personal property) and "capital" in the economic sense.[4][5]

Older English sources like King James Version of the Bible refer to livestock in general as cattle (as opposed to the word deer which then was used for wild animals). Additionally other species of the genus Bos are sometimes called wild cattle. Today, the modern meaning of "cattle", without any other qualifier, is usually restricted to domesticated bovines.

Types of cattle

An intact adult male is called a "bull." An adult female who has had more than one or two calves (depending on regional usage) is called a "cow." The adjective applying to cattle in general is usually "bovine." Young cattle are called calves until they are weaned, when they become weaners until they are a year old in some areas, in other areas, particularly with beef cattle, they may be known as feeder-calves or simply feeders. After that, they are referred to as "yearlings" if between one and two years of age, or by gender: A young female before she has had a calf of her own is called a "heifer" [6][7] (Template:PronEng, "heffer"). A young female that has had only one calf is occasionally called a "first-calf heifer." An older (usually over 500 kg) castrated male is referred to as a "bullock" in the British Isles and Australasia, though the term refers to a young bull in North America. The term "steer" is generally used to denote a young castrated male, unless kept for draft purposes, in which case it is called an "ox" (plural "oxen") (in North America, draft cattle are called "working steers" until they are 4 years of age, at which time the term "oxen" applies). In the USA, though the term "steer" is used as the generic term for a castrated male, in the extremely uncommon situation where an animal is castrated as an adult, the term "stag" is technically correct, though rarely used.[8] Many other large animals species, including whales, hippopotamuses, camels, elk, and elephants, use the terms "bull", "cow" and "calf" to denote males, females, and young within the species.

The singular terminology dilemma

Cattle is both a plural and a mass noun, but there is no singular equivalent: it is a plurale tantum. Thus one may refer to "three cattle" or "some cattle", but not "one cattle". There is no universally used singular equivalent in modern English to "cattle", other than the gender and age-specific terms such as bull, steer, heifer, and so on.

Strictly speaking, the singular noun for the domestic bovine was "ox": a bull is a male ox and a cow is a female ox.[citation needed] However, "ox" today is rarely used in this general sense. An ox today generally denotes a draught beast, most commonly a castrated male (but is not to be confused with the unrelated wild musk ox).

"Cow" has been in general use as a singular for the collective "cattle" in spite of the objections of those who point out that it is a female-specific term, rendering phrases such as "that cow is a bull" absurd. However, it is easy to use when a singular is needed and the gender is not known, as in "There is a cow in the road". Further, any herd of fully mature cattle in or near a pasture is statistically likely to consist mostly of cows, so the term is probably accurate. Other than the few bulls needed for breeding, the vast majority of male cattle are castrated as calves and slaughtered for meat before the age of three years. Thus, in a pastured herd, any calves or herd bulls usually are clearly distinguishable from the cows due to distinctively different sizes and clear anatomical differences.

Colloquially, more general non-specific terms may denote cattle when a singular form is needed. Australian, New Zealand and British farmers use the term "beast" or "cattle beast". "Bovine" is also used in Britain. The term "critter" is common in the western United States and Canada, particularly when referring to young cattle. In some areas of the American South (particularly the Appalachian region), where both dairy and beef cattle are present, an individual animal was once called a "beef critter", though that term is becoming archaic.

Other terminology

Obsolete terms for cattle include "neat" (this use survives in "neatsfoot oil", extracted from the feet and legs of cattle), and "beefing" (young animal fit for slaughter).

Cattle raised for human consumption are called "beef cattle". Within the beef cattle industry in parts of the United States, the term "beef" (plural "beeves") is still used in its archaic sense to refer to an animal of either gender. Cows of certain breeds that are kept for the milk they give are called "dairy cows" or "milking cows" (formerly "milch cows" – "milch" was pronounced as "milk"). Most young male offspring of dairy cows are generally sold for veal, and may be referred to as veal calves. In some places, a cow kept to provide milk for one family is called a "house cow".

An onomatopoeia imitating one of the commonest sounds made by cattle is "moo", and this sound is also called lowing. There are a number of other sounds made by cattle, including calves bawling and bulls bellowing (a high-pitched yodeling call). The bullroarer makes a sound similar to a territorial call made by bulls.

Biology

Cattle have one stomach, with four compartments. They are the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum, the rumen being the largest compartment. Cattle sometimes consume metal objects which are deposited in the reticulum, the smallest compartment, and this is where hardware disease occurs. The reticulum is known as the "Honeycomb." The omasum's main function is to absorb water and nutrients from the digestible feed. The omasum is known as the "Many Plies." The abomasum is most like the human stomach; this is why it is known as the "True Stomach".

Cattle are ruminants, meaning that they have a digestive system that allows them to utilize otherwise indigestible foods by repeatedly regurgitating and rechewing them as "cud." The cud is then reswallowed and further digested by specialized microorganisms that live in the rumen. These microbes are primarily responsible for breaking down cellulose and other carbohydrates into volatile fatty acids (VFAs) that cattle use as their primary metabolic fuel. The microbes that live inside of the rumen are also able to synthesize amino acids from non-protein nitrogenous sources such as urea and ammonia. These features allow cattle to thrive on grasses and other vegetation.

The gestation period for a cow is nine months. A newborn calf weighs roughly 25 to 45 kg (55 to 100 lb). Very large steers can weigh as much as 1,800 kg (4,000 pounds), although 600 to 900 kg (1,300 to 1,900 lb) is more usual for adults. Cattle usually live up to about 15 years (occasionally as much as 25 years).

A common misconception about cattle (particularly bulls) is that they are enraged by the color red (something provocative is often said to be "like a red rag to a bull"). This is incorrect, as cattle are red-green colour-blind.[9] [10] [11] The myth arose from the use of red capes in the sport of bullfighting; in fact, two different capes are used. The capote is a large, flowing cape that is magenta and yellow. The more famous muleta is the smaller, red cape, used exclusively for the final, fatal segment of the fight. It is not the color of the cape that angers the bull, but rather the movement of the fabric that irritates the bull and incites it to charge.[12]

Although cattle cannot distinguish red from green, they do have two kinds of colour receptors in their retinas (cone cells) and so are theoretically able to distinguish some colours, probably in a similar way to other red-green colour-blind or dichromatic mammals (such as dogs, cats, horses and up to ten percent of male humans).[13] [14]

Uses of cattle

Cattle occupy a unique role in human history, domesticated since at least the early Neolithic. They are raised for meat (beef cattle), milk (dairy cattle), and hides. They are also used as draft animals and in certain sports. Some consider cattle the oldest form of wealth, and cattle raiding consequently one of the earliest forms of theft.

In Portugal, Spain, Southern France and some Latin American countries, bulls are used in the sport of bullfighting while a similar sport, Jallikattu, is seen in South India; in many other countries this is illegal. Other sports such as bull riding are seen as part of a rodeo, especially in North America. Bull-leaping, a central ritual in Bronze Age Minoan culture (see Bull (mythology)), still exists in south-western France.

The outbreaks of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) have limited some traditional uses of cattle for food, for example the eating of brains or spinal cords.

In modern times, cattle are also entered into agricultural competitions. These competitions can involve live cattle or carcasses.

Cattle husbandry

Cattle are often raised by allowing herds to graze on the grasses of large tracts of rangeland. Raising cattle in this manner allows the productive use of land that might be unsuitable for growing crops. The most common interactions with cattle involve daily feeding, cleaning and milking. Many routine husbandry practices involve ear tagging, dehorning, loading, medical operations, vaccinations and hoof care, as well as training for agricultural shows and preparations. There are also some cultural differences in working with cattle- the cattle husbandry of Fulani men rests on behavioural techniques, whereas in Europe cattle are controlled primarily by physical means like fences.[15]

Breeders can utilize cattle husbandry to reduce M. bovis infection susceptibility by selective breeding and maintaining herd health to avoid concurrent disease.[16] Cattle are farmed for beef, veal, dairy, leather and they are sometimes used simply to maintain grassland for wildlife- for example, in Epping Forest, England. They are often used in some of the most wild places for livestock. Depending on the breed, cattle can survive on hill grazing, heaths, marshes, moors and semi desert. Modern cows are more commercial than older breeds and having become more specialized are less versatile. For this reason many smaller farmers still favor old breeds, like the dairy breed of cattle Jersey.

Oxen

Oxen (singular ox) are large and heavy set breeds of Bos taurus cattle trained as draft animals. Often they are adult, castrated males. Usually an ox is over four years old due to the need for training and to allow it to grow to full size. Oxen are used for plowing, transport, hauling cargo, grain-grinding by trampling or by powering machines, irrigation by powering pumps, and wagon drawing. Oxen were commonly used to skid logs in forests, and sometimes still are, in low-impact select-cut logging. Oxen are most often used in teams of two, paired, for light work such as carting. In the past, teams might have been larger, with some teams exceeding twenty animals when used for logging.

An ox is nothing more than a mature bovine with an "education." The education consists of the animal's learning to respond appropriately to the teamster's (ox driver's) signals. These signals are given by verbal commands or by noise (whip cracks) and many teamsters were known for their voices and language. In North America, the commands are (1) get up, (2) whoa, (3) back up, (4) gee (turn to the right) and (5) haw (turn to the left). Oxen must be painstakingly trained from a young age. Their teamster must make or buy as many as a dozen yokes of different sizes as the animals grow. A wooden yoke is fastened about the neck of each pair so that the force of draft is distributed across their shoulders. From calves, oxen are chosen with horns since the horns hold the yoke in place when the oxen lower their heads, back up, or slow down (particularly with a wheeled vehicle going downhill). Yoked oxen cannot slow a load like harnessed horses can; the load has to be controlled downhill by other means. The gait of the ox is often important to ox trainers, since the speed the animal walks should roughly match the gait of the ox driver who must work with it.

U.S. ox trainers favored larger breeds for their ability to do more work and for their intelligence. Because they are larger animals, the typical ox is the male of a breed, rather than the smaller female. Females are potentially more useful producing calves and milk.

Oxen can pull harder and longer than horses, particularly on obstinate or almost un-movable loads. This is one of the reasons that teams were dragging logs from forests long after horses had taken over most other draught uses in Europe and North America. Though not as fast as horses, they are less prone to injury because they are more sure-footed and do not try to jerk the load.

An "ox" is not a unique breed of bovine, nor have any "blue" oxen lived outside the folk tales surrounding Paul Bunyan, the mythical American logger. A possible exception and antecedent to this legend is the Belgian Blue breed which is known primarily for its unusual musculature and at times exhibits unusual White/Blue, Blue Roan, or Blue coloration. The unusual musculature of the breed is believed to be due to a natural mutation of the gene that codes for the protein Myostatin, which is responsible for normal muscle atrophy.

Many oxen are still in use worldwide, especially in developing countries. In the Third World oxen can lead lives of misery, as they are frequently malnourished. Oxen are driven with sticks and goads when they are weak from malnutrition. When there is insufficient food for humans, animal welfare has low priority.

Ox is also used for various cattle products, irrespective of age, sex or training of the beast – for example, ox-blood, ox-liver, ox-kidney, ox-heart, ox-hide etc.

Cattle in religion, traditions and folklore

- For the mythology and lore connected with the bull, see Bull (mythology).

- The Evangelist St. Luke is depicted as an ox in Christian art.

- In Judaism, as described in Numbers 19:2, the ashes of a sacrificed unblemished red heifer that has never been yoked can be used for ritual purification of people who came into contact with a corpse.

- The ox is one of the 12-year cycle of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar. See: Ox (Zodiac).

- The constellation Taurus represents a bull.

- An apocryphal story has it that a cow started the Great Chicago Fire by kicking over a kerosene lamp. Michael Ahern, the reporter who created the cow story, admitted in 1893 that he had made it up because he thought it would make colorful copy.

- On February 18, 1930 Elm Farm Ollie became the first cow to fly in an airplane and also the first cow to be milked in an airplane.

- The first known law requiring branding in North America was enacted on February 5, 1644 by Connecticut. It said that all cattle and pigs have to have a registered brand or earmark by May 1, 1644.[17]

- The akabeko ([赤べこ, red cow] Error: {{nihongo}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a traditional toy from the Aizu region of Japan that is thought to ward off illness.[18]

- The case of Sherwood v. Walker -- involving a supposedly barren heifer that was actually pregnant -- first enunciated the concept of Mutual mistake as a means of destroying the Meeting of the minds in Contract law. [citation needed]

- The Maasai tribe of East Africa traditionally believe that all cows on earth are the God-given property of the Maasai

Cattle in Hindu tradition

Cows are venerated within the Hindu religion of India. According to Vedic scripture they are to be treated with the same respect 'as one's mother' because of the milk they provide; "The cow is my mother. The bull is my sire."[19] They appear in numerous stories from the Puranas and Vedas, for example the deity Krishna is brought up in a family of cowherders, and given the name Govinda (protector of the cows). Also Shiva is traditionally said to ride on the back of a bull named Nandi. Bulls in particular are seen as a symbolic emblem of selfless duty and religion. In ancient rural India every household had a few cows which provided a constant supply of milk and a few bulls that helped as draft animals. Many Hindus feel that at least it was economically wise to keep cattle for their milk rather than consume their flesh for one single meal.

Gandhi explains his feelings about cow protection as follows:

"The cow to me means the entire sub-human world, extending man’s sympathies beyond his own species. Man through the cow is enjoined to realize his identity with all that lives. Why the ancient rishis selected the cow for apotheosis is obvious to me. The cow in India was the best comparison; she was the giver of plenty. Not only did she give milk, but she also made agriculture possible. The cow is a poem of pity; one reads pity in the gentle animal. She is the second mother to millions of mankind. Protection of the cow means protection of the whole dumb creation of God. The appeal of the lower order of creation is all the more forceful because it is speechless."

In heraldry

Cattle are represented in heraldry by the bull.

-

Arms of Bielsk Podlaski, Poland -

Arms of Turek, Poland

Present status

The world cattle population is estimated to be about 1.3 billion head. India is the nation with the largest number of cattle, about 400 million, followed by Brazil and China, with about 150 million each, and the United States, with about 100 million. Africa has about 200 million head of cattle, many of which are herded in traditional ways and serve largely as tokens of their owners' wealth. Europe has about 130 million head of cattle (CT 2006, SC 2006).

Cattle today are the basis of a many billion dollar industry worldwide. The international trade in beef for 2000 was over $30 billion and represented only 23 percent of world beef production. (Clay 2004). The production of milk, which is also made into cheese, butter, yogurt, and other dairy products, is comparable in size to beef production and provides an important part of the food supply for much of the world's people. Cattle hides, used for leather to make shoes and clothing, are another important product. In India and other poorer nations, cattle are also important as draft animals as they have been for thousands of years.

Environmental impact

Cattle are "responsible for 18% of greenhouse gases," states a 400-page United Nations report from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). [20]Cattle are blamed for a host of other environmental crimes, from acid rain to the introduction of alien species, from producing deserts to creating dead zones in the oceans, from poisoning rivers and drinking water to destroying coral reefs.

The report, entitled Livestock's Long Shadow, also surveys the damage done by sheep, chickens, pigs and goats. But in almost every case, the world's 1.5 billion cattle are cited as being most to blame. The report concludes that, unless changes are made, the massive damage reckoned to be due to livestock may more than double by 2050, as demand for meat increases. One of the cited changes suggests that intensification of the livestock industry may be necessary, since intensification leads to fewer cattle for a given level of production.[21]

Some of the microbes respire in the gut by an anaerobic process known as methanogenesis (producing the gas methane). Cattle emit a large amount of methane, 95% of it through eructation or burping, not flatulence.[22] As the carbon in the methane comes from the digestion of vegetation produced by photosynthesis, its release into the air by this process would normally be considered harmless, because there is no net increase in carbon in the atmosphere — it's removed as carbon dioxide from the air by photosynthesis and returned to it as methane. But methane is a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, having a warming effect 23 times greater[23], and so the methane gas produced by livestock is a significant contributor to the increase in greenhouse gases.[24][unbalanced opinion?] Research is underway on methods of reducing this source of methane, by the use to dietary supplements, or treatments to reduce the proportion of methanogenetic microbes, perhaps by vaccination.[25]

Alternative views on this issue note that the problem may not be cattle per se, but rather the concentration of cattle into feedlots, where they are fed a concentrated high-corn diet which produces rapid weight gain, but has side effects which include increased acidity in the digestive system. Manure and other byproducts of concentrated agriculture also have environmental consequences.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ http://cattle-today.com/

- ^ Takeda, Kumiko (April 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Nepalese domestic dwarf cattle Lulu". Animal Science Journal. 75 (2). Blackwell Publishing: 103–110. doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2004.00163.x. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Cattle". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Chattel". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Capital". Online Etymological Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- ^ "Definition of heifer". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|month=,|accessmonthday=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Warren, Andrea. "Pioneer Girl: Growing Up on the Prairie" (PDF). Lexile. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ^ http://www.smithfieldfoods.com/Understand/Glossary/#gloss_s

- ^ http://www.beef-cattle.com/beef-cattle-biology-and-terminology.htm

- ^ http://www.itla.net/index.cfm?sec=Longhorn_Information&con=handling

- ^ http://iacuc.tennessee.edu/pdf/Policies-AnimalCare/Cattle-BasicCare.pdf

- ^ http://www.beef-cattle.com/beef-cattle-biology-and-terminology.htm

- ^ Jacobs, G. H., J. F.Deegan, and J. Neitz. 1998. Photopigment basis for dichromatic color vision in cows, goats and sheep. Vis. Neurosci. 15:581–584

- ^ Perception of Color by Cattle and its Influence on Behavior C.J.C. Phillips* and C. A. Lomas†2 J. Dairy Sci. 84:807–813

- ^ Lott, Dale F. (October 1979). "Applied ethology in a nomadic cattle culture". Applied Animal Ethology. 5 (4). Elsevier B.V.: 309–319. doi:10.1016/0304-3762(79)90102-0.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Krebs JR, Anderson T, Clutton-Brock WT; et al. (1997). "Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers: an independent scientific review" (PDF). Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Retrieved 2006-09-04.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kane, J. (1997). Famous First Facts. New York, NY: H.W. Wilson. p. 5. ISBN 0-8242-0930-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Madden, Thomas (May 1992). "Akabeko". OUTLOOK. Online copy accessed 18 January 2007.

- ^ Mahabharata, Book 13-Anusasana Parva, Section LXXVI

- ^ "Livestock a major threat to environment". FAO Newsroom.

- ^ http://www.virtualcentre.org/en/library/key_pub/longshad/A0701E00.htm

- ^ "Bovine belching called udderly serious gas problem." Los Angeles Times, Sunday, July 13, 2003

- ^ (pie charts)

- ^ Spencer Weart: The Discovery of Global Warming: "Other Greenhouse Gases". June 2007.

- ^ "Triad bid to stop belching". Retrieved 2006-01-04.

- Bhattacharya, S. 2003. Cattle ownership makes it a man's world. Newscientist.com. Retrieved December 26, 2006.

- Cattle Today (CT). 2006. Website. Breeds of cattle. Cattle Today. Retrieved December 26, 2006)

- Clay, J. 2004. World Agriculture and the Environment: A Commodity-by-Commodity Guide to Impacts and Practices. Washington, D.C., USA: Island Press. ISBN 1559633700.

- Clutton-Brock, J. 1999. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge UK : Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521634954.

- Huffman, B. 2006. The ultimate ungulate page. UltimateUngulate.com. Retrieved December 26, 2006.

- Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). 2005. .Bos taurus. Global Invasive Species Database.

- Nowak, R.M. and Paradiso, J.L. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland, USA: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- Oklahoma State University (OSU). 2006. Breeds of Cattle. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). 2004. Holy cow. PBS Nature. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- Rath, S. 1998. The Complete Cow. Stillwater, Minnesota, USA: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0896583759.

- Raudiansky, S. 1992. The Covenant of the Wild. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 0688096107.

- Spectrum Commodities (SC). 2006. Live cattle. Spectrumcommodities.com. Retrieved January 5, 2007.

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey, USA: Plexus Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0937548081.

- Yogananda, P. 1946. The Autobiography of a Yogi. Los Angeles, California, USA: Self Realization Fellowship. ISBN 0876120834.

External links

- Cowhq: A site dedicated to cows and cow information

- La Fratta, Italian Chianina cattle breeders - Sinalunga, Siena, Italy

- Western Watersheds Project - Cows versus Conservation

- Cattle Breeds website - Oklahoma State University

- Cattle.com - Comprehensive Beef Portal

- PBS Nature: Holy Cow (about cows in general)

- UK Lincoln Red Cattle Society

- SearchCattle.com - Specialized Cattle Search Engine

- Photo Gallery with Images of Cattle

- Prairie Ox Drovers -Information, help, and encouragement to get started with oxen.

- "Do McDonald's milkshakes contain seaweed?", The Straight Dope, 27-Nov-1992

- The Cattle Pages - Directory of information, cattle associations, and cattle breeders

- "45 Fun Facts About Cows"

- Mumu, cow cattle virtual museum