Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains (Template:Lang-ru, Uralskiye gory) are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the Ural River and northwestern Kazakhstan.[1] Their eastern side is usually considered the natural boundary between Europe and Asia. The mountains lie within the Ural geographical region and significantly overlap with the Ural Federal District and Ural economic region. They are rich in various deposits, including metal ores, coal, precious and semi-precious stones, and since 18th century have been the major mineral base of Russia.

Etymology

In Greco-Roman antiquity, Pliny the Elder thought that the Urals correspond to the Riphean Mountains mentioned by various authors. They were mentioned in Arabic sources in the 10th century and were also known as the Great Stone Belt in Russian history and folklore from the 11th century. In the mid-16th – early 17th century, the southern parts became known as Ural, which name later spread on the entire area. The name probably originated from Turkic "aral". This word literally means "island" and was used for any territory different from the surrounding terrain. From the 13th century, in Bashkortostan there is a legend about a hero named Ural. He sacrificed his life for the sake of his people and they poured a stone pile over his grave which later turned into the Ural Mountains.[2][3][4]

History

The first ample geographic survey of the Ural Mountains was completed in the early 18th century by the Russian historian and geographer Vasily Tatishchev under the orders of Peter I. Earlier, in the 17th century, rich ore deposits were discovered in the mountains and their systematic extraction began in the early 18th century, eventually turning the region into the largest mineral base of Russia.[1][2]

One of the first scientific descriptions of the mountains was published in 1770–71. Over the next century, the region was studied by scientists from a number of countries, including Russia (geologist Alexander Karpinsky, botanist P.N. Krylov and zoologist L.P. Sabaneev), England (geologist Sir Roderick Murchison), France (paleontologist Edouard de Verneuil), and Germany (naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, geologist Alexander Keyserling).[1][5] In 1845, Murchison, who had according to The Encyclopedia Britannica"compiled the first geologic map of the Urals in 1841",[1] published The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains with de Verneuil and Keyserling.[5][6]

Geography and topography

The Ural Mountains extend about 2,500 km (1,550 mi) from the Kara Sea to the Kazakh steppes along the northern border of Kazakhstan. Vaygach Island and the island of Novaya Zemlya form a further continuation of the chain on the north. Geographically this range marks the northern part of the border between the continents of Europe and Asia. Its highest peak is Mount Narodnaya (1,895 m or 6,213 ft).[1]

By topography and other natural features, Ural is divided, from north to south, into the Polar (or Arctic), Nether-Polar (or Sub-Arctic), Northern, Central and Southern parts. The Polar Ural extends for about 385 kilometers (240 miles) from the Mount Konstantinov Kamen in the north to the Khulga River in the south; it has an area of about 25,000 km² and a strongly dissected relief. The maximum height is 1,499 meters (4,915 feet) at the Payer Mountain and the average height is 1,000–1,100 meters (3,280–3,605 feet). The mountains of Polar Ural could have sharp ridges but there are also flattened or rounded tops.[2][1]

The Nether-Polar Ural is wider (up to 150 km) and higher than the Polar Ural, with the highest peaks of 1,895 m (6,213 feet, Mount Narodnaya), 1,878 m (6,157 feet, Mount Karpinsky (Urals)) and 1,662 m (5,450 feet, Manaraga). It extends for more than 225 kilometers (140 miles) south to the Shchugor River. Its many ridges have sawtooth shape and are dissected by river valleys. Both Polar and Nether-Polar Urals are typically Alpine; they bear traces of Pleistocene glaciation and permafrost and have a rather developed modern glaciation that includes 143 glaciers.[2][1]

The Northern Ural consists of a series of parallel ridges with the height up to 1,000–1,200 m and longitudinal depressions. They are elongated from north to south and stretch for about 560 km (340 miles) from the Usa River. Most of the tops are flattened, but those of the highest mountains, such as Telnosiz (1,617 m or 5,300 ft) and Konzhakovsky Stone (1,569 m or 5,144 ft) have dissected topography. Intensive weathering has produced vast areas of eroded stones on the mountain slopes and summits of the northern areas.[2][1]

The Central Ural is the lowest part of Urals, with the highest mountain of 994 m (Basegi) and smooth mountain tops; it extends south from the Ufa River.[2]

The relief of Southern Ural is more complex, with numerous valleys and parallel ridges directed south-west and meridionally. Its maximum height is 1,640 m (5,377 ft, Mount Yamantau) and the widths reaches 250 km. The Southern Ural extends some 550 km (340 mi) up to the sharp westward bend of the Ural River and terminates in the wide Mughalzhar Hills.[1]

|

|

|

|

| Mountain formation near Saranpaul, Nether-Polar Urals | Rocks in a river, Nether-Polar Urals | Mountain Big Iremel | Entry to the Ignateva Cave, South Urals |

Geology

The Urals are among the world's oldest extant mountain ranges. For its age of 250 to 300 million years, the elevation of the mountains is unusually high. They were formed during the late Carboniferous period, when western Siberia collided with eastern Baltica (connected to Laurentia (North America) to form the minor supercontinent of Euramerica) and Kazakhstania to form the supercontinent of Laurasia. Later Laurasia and Gondwana collided to form the supercontinent of Pangaea, which subsequently broke itself apart into the seven continents known today. Europe and Siberia have remained joined together ever since. Many deformed and metamorphosed rocks, mostly of Paleozoic period, surface within the Urals. The sedimentary and volcanic layers are folded and broken, and form meridional bands. The sediments to the west of the Ural Mountains are formed by limestone, dolomite and sandstone left from ancient shallow seas. The eastern side is dominated by basalts similar to the rocks of the bottom of the modern oceans.[2]

The western slope of the Ural Mountains has predominantly Karst topography, especially in the basin of the Sylva River, which is a tributary of the Chusovaya River. It is composed of severely eroded sedimentary rocks (sandstones and limestones) that are about 350 million years old. There are many caves, Karst sinks and underground streams. The Karst topography is much less developed on the eastern slopes. They are relatively flat, with some hills and rocky outcrops and contain alternating volcanic and sedimentary layers dated to the middle Paleozoic period.[2] Most high mountains consist of weather-resistant minerals such as quartzite, schist and gabbro that are between 570 and 395 million years old. The river valleys are laid with limestone.[1]

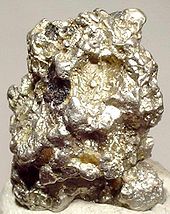

Ural Mountains contain about 48 species of economically valuable ores and minerals. Eastern regions are rich in chalcopyrite, nickel oxide, gold, platinum, chromite and magnetite ores, as well as in coal (Chelyabinsk Oblast), bauxite, talc, fireclay and abrasives. Western Ural contains deposits of coal, oil, natural gas (Ishimbay and Krasnokamsk areas) and potassium salts. Both slopes are rich in bituminous coal and lignite, and the largest deposit of bituminous coal is in the north (Pechora field). The specialty of Urals is previous and semi-precious stones, such as emerald, amethyst, aquamarine, jasper, rhodonite, malachite and diamond. Some of the deposits, such as the magnetite ores at Magnitogorsk are already nearly depleted.[2][1]

|

|

|

|

| Andradite | Beryl | Platinum | Quartz |

Rivers and lakes

Many rivers originate in the Ural Mountains; most of them belong to the basin of the Arctic Ocean but some drain into the Caspian Sea. Almost all northern rivers are part of the watershed of the Ob River which flows into the Kara Sea. They include Tobol, Tavda, Iset, Tura and Severnaya Sosva Rivers. The Pechora River, flows on the western slope of the Polar, Nether-Polar, and Northern Urals and falls into the Barents Sea. Its major tributaries are the Ilych, Shchugor, and Usa. The rivers freeze for more than half a year.[1][2]

The southern rivers are Kama which feeds the Volga River and the Ural River which flows south from the Urals and drains into the Caspian Sea. The tributaries of the Kama include the Vishera, Chusovaya, and Belaya rivers and originate both in the eastern and western slopes. Generally, the western rivers are more affluent than the eastern ones, especially in the Northern and Nether-Polar regions. Rivers are slow in the Southern Ural. This is because of low precipitation and relatively warm climate resulting in less snow and more evaporation.[1][2]

Most lakes are concentrated in the eastern slope of the Southern and Central Urals, such as the Uvildy, Itkul, Turgoyak, and Tavatuy lakes. The western slope also has lakes, but those are significantly smaller. The lakes of Polar Ural fill deep glacial valleys, the deepest being the Lake Bolshoye Shchuchye (136 m or 446 feet). Some lakes have medicinal muds and the associated spas and sanatoriums.[1][2]

Climate

The climate of Urals is continental. The mountain ridges elongated from north to south, effectively absorb sunlight thereby increasing the temperature. The areas west to the Ural Mountains are 1–2 °C warmer in winter than the eastern regions because the former are warmed by the Atlantic winds whereas the eastern slopes are chilled by the Siberian air masses. The average January temperatures increase in the western areas from –20 °C in the Polar to –15 °C in the Southern Urals and the corresponding temperatures in July are 10 °C and 20 °C. The western areas also received more rainfall than the eastern ones by 150–300 mm per year. This is because the mountains trap the clouds brought from the Atlantic Ocean. The highest precipitation (1000 mm) is in the Northern Ural that causes the average height of snow up to 100 cm (3.3 ft). The eastern parts receive from 500–600 mm on the north to 300–400 mm on the south. Maximum precipitation occurs in the summer and the winter is dry because of the Siberian anticyclone.[2][1]

Flora

The landscapes of Urals change both in the latitudinal and vertical directions and are dominated by steppes and forests. The southern area of the Mughalzhar Hills is a semidesert. Steppes lie mostly in the southern and especially south-eastern Urals. Meadow steppes have developed in the lower parts of mountain slopes and are covered with various clovers, daisies, filipendula, meadow-grass and foxtail millet, reaching the height of 60–80 cm. Many lands are cultivated. Moving to the south, the meadow steppes become more sparse, dry and low. The steep gravelly slopes of mountains and hills of eastern slopes of the Southern Ural are mostly covered with rocky steppes. Valleys of the rivers contain willow, poplar and caragana shrubs.[2]

Forest landscapes of Urals are diverse, especially the southern part. The western areas are dominated by dark coniferous taiga forests which change to mixed and deciduous forests on the south. The eastern mountain slopes have light coniferous taiga forests. Southern Ural is most diverse in the forest composition; here together with coniferous forests also abundant are other tree species such as larch, oak, birch, maple and elm. The Northern Ural is dominated by Siberian species of fir, cedar, spruce and pine. Forests are much more sparse in Polar Ural. Whereas in other Ural Mountains areas they grow up to the heights of 1 km, the forests cease at 250–400 m in the Polar Urals. The polar forests are low and are mixed with swamps, lichens, bogs and shrubs. Abundant are dwarf birch, mosses and berries (blueberry, cloudberry, black crowberry, etc.). The Virgin Komi Forests in the northern Urals are recognized as a World Heritage site.[2]

Fauna

Ural forests are inhabited by animals typical of Siberia, such as elk, brown bear, fox, wolf, wolverine, lynx, squirrel and sable (north only). Because of the easy accessibility of the mountains there are no specifically mountanous species. In the Middle Ural, one can meet a rare mixture of sable and pine marten named kidus. In the Southern Ural, frequent are badger and black polecat. Reptiles and amphibians live mostly in the Southern and Central Ural and are represented by the common viper, lizards and grass snakes. Bird species are represented by capercaillie, black grouse, hazel grouse, Spotted Nutcracker and cuckoos. In summers, South and Middle Urals are visited by songbirds, such as nightingale and redstart.[2][1]

Steppes of the Southern Urals are dominated by hares and rodents such as gophers, susliks and jerboa. There are many birds of prey such as Lesser Kestrel and buzzards. The animals of the Polar Ural are few and are characteristic of the tundra and include Arctic Fox, tundra partridge, lemming and reindeer. The birds of those areas include rough-legged buzzard, Snowy Owl and Rock Ptarmigan.[2][1]

|

|

|

|

| Gopher | Suslik | Wolverine | Polecat |

Ecology

The continuous and intensive economic development of the last centuries has affected the fauna, and the wildlife is very much reduced around all industrial centers. During World War II, hundreds of factories were evacuated from the Western Russia right before the German occupation, flooding the Urals with industry. The conservation measures include establishing national wildlife parks. Those include the Pechoro-Ilych in the Northern Urals, Basegi and Visim in the Central Urals, and Ilmen and Bashkir in the Southern Urals.[1]

After World War II, a plutonium-producing facility was established in the Southern Urals in Chelyabinsk-40 and Chelyabinsk-65 (now Ozyorsk. It produced plutonium from 1949 until 1990. In the 1950s-60s, the plant regularly dumped much radioactive waste into the Techa River and Lake Karachay, and the accidents brought more radioactive pollution. In 1957, 23,000 square kilometers (9,000 square mi) were contaminated as a result of a storage tank explosion.[1]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Ural Mountains, Encyclopedia Britannica on-line

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Ural (geographical)". Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- ^ *Ludmila Koriakova and Andrei Epimakhov (2007). The Urals and Western Siberia in the Bronze and Iron Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 338. ISBN 0521829283.

- ^ Ural, toponym Chlyabinsk Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- ^ a b Geological Society of London (1894). The Quarterly journal of the Geological Society of London. The Society. p. 53. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ cf. Murchison, Roderick Impey; Edouard de Verneuil; Alexander Keyserling (1845). The Geology of Russia in Europe and the Ural Mountains. John Murray. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

External links

- Template:Wikitravelpar

- Peakbagger.com page on the Ural Mountains

- Ural Expeditions & Tours page on the five parts of the Ural Mountains