Tutankhamun

Nebkheperre Tutankhamun (alternate transcription Tutankhamen), named Tutankhaten early in his life, was Pharaoh of the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt (ruled 1334 BC – 1325 BC), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. His original name, Tutankhaten, meant "Living Image of Aten", while Tutankhamun meant "Living Image of Amun". He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters.

In historical terms, Tutankhamun is of only moderate significance, primarily as a figure managing the beginning of the transition from the heretical Atenism of his predecessor Akhenaten back to the familiar Egyptian religion. As Tutankhamun began his reign at age 9, a considerable responsibility for his reign must also be assigned to his vizier and eventual successor, Ay. Nonetheless, Tutankhamun is in modern times the most famous of the Pharaohs, and the only one to have a nickname in popular culture ("King Tut"). The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter of his nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage and sparked a renewed public interest in Ancient Egypt, of which Tutankhamun remains the popular face.

Life

Family

Tutankamun's parentage is uncertain. An inscription calls him a king's son, but it is debated which king was meant. Most scholars think that he was probably a son either of Amenhotep III (though probably not by his Great Royal Wife Tiye), or of Amenhotep III's son Amenhotep IV (better known as Akhenaten), perhaps with his enigmatic second queen, Kiya. It should be noted that when Tutankhaten succeeded Akhenaten to the throne, Amenhotep III had been dead for some time; the duration is thought by some Egyptologists to have been seventeen years, although on this, as on so many questions about the Amarna period, there is no scholarly consensus. Tutankhamun ruled Egypt for eight to ten years; examinations of his mummy show that he was a young adult when he died. Recent CT scans place Tut at age 19. This conclusion was reached after images of Tut's teeth were examined, and were found to be consistent with the teeth of a 19 year old. That would place his birth around 1342 BC-1340 BC, and would make it less likely that Amenhotep III was his father.

Tutankhamun was married to Ankhesenpaaten, a daughter of Akhenaten. Ankhesenpaaten also changed her name from the -aten endings to the -amun ending, becoming Ankhesenamun. They had two known children, both stillborn girls – their mummies were discovered in his tomb.

Reign

During Tutankhamun's reign, Akhenaten's Amarna revolution (Atenism) began to be reversed. Akhenaten had attempted to supplant the existing priesthood and gods with a god who was until then considered minor, Aten. In year 3 of Tutankhamun's reign (1331 BC), when he was still a boy of about 11 and probably under the influence of two older advisors (notably Akhenaten's vizier Ay), the ban on the old pantheon of gods and their temples was lifted, the traditional privileges restored to their priesthoods, and the capital moved back to Thebes. The young pharaoh also adopted the name Tutankhamun, changing it from his birth name Tutankhaten. Because of his age at the time these decisions were made, it is generally thought that most if not all the responsibility for them falls on his vizier Ay and perhaps other advisors.

Events after his death

A now-famous letter to the Hittite king Suppiluliumas I from a widowed queen of Egypt, explaining her problems and asking for one of his sons as a husband, has been attributed to Ankhesenamun (among others). Suspicious of this good fortune, Suppiluliumas I first sent a messenger to make inquiries on the truth of the young queen's story. After reporting her plight back to Suppilulumas I, he sent his son, Zannanza, accepting her offer. However, he got no further than the border before he died, perhaps murdered. If Ankhesenamun were the queen in question, and his death a murder, it was probably at the orders of Horemheb or Ay, who both had the opportunity and the motive.

In any event, after Tutankhamun's death Ankhesenamun married Ay (a signet ring, with both Ay and Ankehesenamun's name was found), possibly under coercion, and shortly afterwards disappeared from recorded history.

Tutankhamun was briefly succeeded by the elder of his two advisors, Ay, and then by the other, Horemheb, who obliterated most of the evidence of the reigns of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay.

Name

Under Atenism, Tutankhamun was named Tutankhaten, which in Egyptian hieroglyphs is:

| |

Technically, this name is transliterated as twt-ˁnḫ-ỉtn.

At the reintroduction of the old pantheon, his name was changed. It is transliterated as twt-ˁnḫ-ỉmn ḥq3-ỉwnw-šmˁ, and often realised as Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning "Living image of Amun, ruler of Southern Heliopolis". On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a praenomen. This is transliterated as nb-ḫprw-rˁ, and realised as Nebkheperure, meaning "Lord of the forms of Re". The name Nibhurrereya in the Amarna letters may be a variation of this praenomen.

Cause of death

For a long time the cause of Tutankhamun's death was unknown, and was the root of much speculation. How old was the king when he died? Did he suffer from any physical abnormalities? Had he been murdered? Many of these questions were finally answered in early 2005 when the results of a set of CT scans on the mummy were released.

The body was originally inspected by Howard Carter’s team in the early 1920s, though they were primarily interested in recovering the jewelry and amulets from the body. To remove the objects from the body, which in many cases were stuck fast by the hardened embalming resins used, Carter's team cut up the mummy into various pieces: the arms and legs were detached, the torso cut in half and the head was severed. Hot knives were used to remove it from the golden mask to which it was cemented by resin. Since the body was placed back in its sarcophagus in 1926, the mummy has subsequently been X-rayed three times: first in 1968 by a group from the University of Liverpool, then in 1978 by a group from the University of Michigan and finally in 2005 a team of Egyptian scientists led by Secretary General of the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities Dr. Zahi Hawass conducted a CT scan on the mummy.

Early (pre-2005) X-rays of his mummy had revealed a dense spot at the lower back of the skull. This had been interpreted as a chronic subdural hematoma, which would have been caused by a blow. Such an injury could have been the result of an accident, but it had also been suggested that the young pharaoh was murdered. If this is the case, there are a number of theories as to who was responsible: one popular candidate was his immediate successor Ay. Interestingly, there are seemingly signs of calcification within the supposed injury, which if true meant Tutankhamun lived for a fairly extensive period of time (on the order of several months) after the injury was inflicted.

Much confusion had been caused by a small loose sliver of bone within the upper cranial cavity, which was discovered from the same X-ray analysis. Some people have mistaken this visible bone fragment for the supposed head injury. In fact, since Tutankhamun's brain was removed post mortem in the mummification process, and considerable quantities of now-hardened resin introduced into the skull on at least two separate occasions after that, had the fragment resulted from a pre-mortem injury, it almost certainly would not still be loose in the cranial cavity. It therefore almost certainly represented post-mummification damage.

2005 research

On March 8, 2005, Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass revealed the results of a CT scan performed on the pharaoh's mummy. The scan uncovered no evidence for a blow to the back of the head as well as no evidence suggesting foul play. There was a hole in the head, but it appeared to have been drilled, presumably by embalmers. A fracture to Tutankhamun's left thighbone was interpreted as evidence that suggests the pharaoh badly broke his leg before he died, and his leg became infected; however, members of the Egyptian-led research team recognized as a less likely possibility that the fracture was caused by the embalmers. 1,700 images were produced of Tutankhamun's mummy during the 15-minute CT scan. The research also showed that the pharaoh had cleft palate [1].

Much was learned about the young king's life. His age at death was estimated at 19 years, based on physical developments that set upper and lower limits to his age. The king had been in general good health, and there were no signs of any major infectious disease or malnutrition during childhood. He was slight of build, and was roughly 170 cm (5½ ft) tall. He had large front incisor teeth and the overbite characteristic of the rest of the Thutmosid line of kings to which he belonged. He also had a pronounced dolichocephalic (elongated) skull, though it was within normal bounds and highly unlikely to have been pathologic in cause. Given the fact that many of the royal depictions of Akhenaten (possibly his father, certainly a relation), often featured an elongated head, it is likely an exaggeration of a family trait, rather than a distinct abnormality more typical of a condition like Marfan's syndrome, as had been suggested. A slight bend to his spine was also found, but the scientists agreed that there was no associated evidence to suggest that it was pathological in nature, and that it was much more likely to have been caused during the embalming process. This ended speculation based on the previous X-rays that Tutanhkamun had suffered from scoliosis.

The 2005 conclusion by a team of Egyptian scientists, based on the CT scan findings, confirmed that Tutankhamun died of a swift attack of gangrene after breaking his leg. After consultations with Italian and Swiss experts, the Egyptian scientists found that the fracture in Tutankhamun's left leg most likely occurred only days before his death, which had then become gangrenous and led directly to his death. The fracture was not sustained during the mummification process or as a result of some damage to the mummy as claimed by Howard Carter. The Egyptian scientists have also found no evidence that he had been struck in the head and no other indication he was killed, as had been previously speculated.

Despite the relatively poor condition of the mummy, the Egyptian team found evidence that great care had been given to the body of Tutankhamun during the embalming process. They found five distinct embalming materials, which were applied to the body at various stages of the mummification process. This counters previous assertions that the king’s body had been prepared carelessly and in a hurry.

Tutankhamun in popular culture

Tutankhamun is the world's best known pharaoh, partly because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. He has also entered popular culture - he has, for example, been commemorated in the whimsical song "King Tut" by comedian Steve Martin, and in a series of historical novels by Lynda Robinson. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his forward to the 1977 edition of Carter's The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, "The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's kings has become in death the most renowned."

Discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb

Tutankhamun's existence is believed to have been mostly forgotten at some point not too long after his death, until the 20th century. His tomb was opened hurriedly by grave robbers a few years after his death, but few items were stolen and the tomb was resealed by an unknown party. No one broke into the tomb afterwards, exactly because he and it had been forgotten.

The British Egyptologist Howard Carter (employed by Lord Carnarvon) discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (since designated KV62) in The Valley of The Kings on November 4, 1922 near the entrance to the tomb of Ramses VI, thereby setting off a renewed interest in all things Egyptian in the modern world. Carter contacted his patron, and on November 26 that year both men became the first people to enter Tutankhamun's tomb in over 3000 years. After many weeks of careful excavation, on February 16, 1923 Carter opened the inner chamber and first saw the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun.

For many years, rumors of a "curse" (probably fueled by newspapers at the time of the discovery) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had first entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicates no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not. Indeed, most lived past 70.

Ancient Egyptian senet games were found in the tomb [2].

As an aside, there has been some more recent speculation regarding the treasures found in Tutankhamun's tomb, since it was noted during examination that many of the artifacts found therein had not originally been created for the boy king - his death has been suggested as being both sudden and far too early for appropriate burial treasures to have been accumulated and prepared for when the Pharoah died. Consequently, or so it was suggested, the treasures were reclaimed from the tomb of another - some suspecting that the burial treasures of Nefertiti were among these - and retooled in order to be appropriate for burial with Tutankhamun.

Evidence for this theory include many of the statues supposed to depict Tutankhamun having feminine physical features, as well as several inscriptions with the cartouche of the Pharoah clearly having been removed (thus suggesting that the original cartouche was not that of Tutankhamun), including several inscriptions on the table upon which the coffin was found.

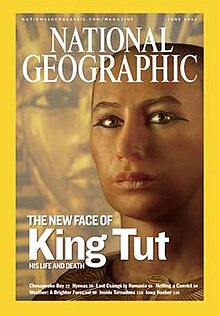

Tutankhamun's appearance

In 2005, three teams of scientists (Egyptian, French and American), in partnership with the National Geographic Society, developed a new facial likeness of Tutankhamun. The Egyptian team worked from 1,700 three-dimensional CT scans of the pharaoh's skull. The French and American teams worked plastic molds created from these -- but the Americans were never told whom they were reconstructing.[3] All three teams created silicon molds bearing what decades of archaeological and forensic research show to be the most accurate replications of Tutankhamun's features since his royal artisans prepared the splendors of his tomb.

Skin tone

Though modern technology can reconstruct Tutankhamun's facial structure with a high degree of accuracy based on CT data from his mummy, correctly determining his skin tone is impossible. The problem is not a lack of skill on the part of Ancient Egyptians; the accuracy of their portraiture is world renowned, especially in sculpture (see Nefertiti). Egyptian artisans distinguished accurately among different ethnicities, but sometimes depicted their subjects in totally unreal colors, the purposes for which aren't completely understood. Thus no absolute consensus on King Tut's skin tone is possible.

Terry Garcia, National Geographic's executive vice president for mission programs, said, in response to some protestors of the King Tut reconstruction:

- The big variable is skin tone. North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone, and we say, quite up front, 'This is midrange.' We'll never know for sure what his exact skin tone was or the color of his eyes with 100 percent certainty. ... Maybe in the future, people will come to a different conclusion. [4]

Exhibitions

The splendors of Tutankhamun's tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the most well-known exhibition tour, which more than a million people visited, is Treasures of Tutankhamun, organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 17 November, 1976 through 15 March, 1977 (and extended by other galleries until 1979).

An excerpt from the site of the National Gallery of Art:

- "...55 objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun included the boy-king's solid gold funeral mask, a gilded wood figure of the goddess Selket, lamps, jars, jewelry, furniture, and other objects for the afterlife. This exhibition established the term 'blockbuster.' A combination of the age-old fascination with ancient Egypt, the legendary allure of gold and precious stones, and the funeral trappings of the boy-king created an immense popular response. Visitors waited up to 8 hours before the building opened to view the exhibition. At times the line completely encircled the West Building."[5]

In 2005, hoping to inspire a whole new generation, Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with the National Geographic Society, launched a new American tour of Tutankhamun's treasures, this time called "Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs." It is expected to draw more than three million people.[6] The exhibition started in Los Angeles, California.

Notes

- ^3 Two life-size guardian statues discovered protecting the main burial chamber do show Tutankhamun as completely jet-black, save for gold highlights around his eyes and on his head. To the non-professional these may cause confusion, interpreted wrongly as accurate gauges of Tutankhamun's complexion. In fact, these figures represent the king on his voyage through the pitch darkness of the underworld -- a very significant afterlife ritual.[7]

See also

Further reading

- Howard Carter, Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen. Courier Dover Publications, June 1, 1977, ISBN 0486235009 The semi-popular account of the discover and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- C. Nicholas Reeves, The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, November 1, 1990, ISBN 0500050589 (hardcover)/ISBN 0500278105 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb

- T. G. H. James, Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, September 1, 2000, ISBN 1586630326 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt, Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamen: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0821201514 (1976 reprint, hardcover)/ISBN 0140116656 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Thomas Hoving, The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, October 15, 1978, ISBN 0671243055 (hardcover)/ISBN 0815411863 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen: A True Story. Putnam Adult, April 13, 1998, ISBN 0425166899 (paperback)/ISBN 0399143831 (hardcover)/ISBN 0613289676 (School & Library Binding)

- Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards, Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0345273494 (paperback)/ISBN 0670727237 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

External links

- End Paper: A New Take on Tut's Parents by Dennis Forbes (KMT 8:3 . FALL . 1997 � KMT Communications)

- The mummy's curse: historical cohort study (Mark R Nelson, British Medical Journal 2002;325:1482-1484)

- Tutankhamun profile

- Life of King Tut

- Theban Mapping Project - Includes detailed maps of this and most of the other tombs.

- William Max Miller's Theban Royal Mummy Project

Appearance/death