White flight

This article's lead section may be too long. (September 2011) |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Racial and ethnic segregation |

|---|

|

White flight has been a term that originated in the United States, starting in the mid-20th century, and applied to the large-scale migration of whites of various European ancestries from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogeneous suburban or exurban regions. It was first seen as originating from fear and anxiety about increasing minority populations. The term has more recently been applied to other migrations by whites, from older, inner suburbs to rural areas, as well as from the US Northeast and Midwest to the milder climate in Southeast and Southwest, but this is a change from its original cause and meaning.[1][2][3]

The term has also been used for large scale post-colonial emigration of whites from Africa.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

Following World War II, there was pent-up housing demand in the US, and widespread suburban development took place. In addition, some working-class and middle-class white families felt pressure from increases in minority populations and overcrowding in cities. They moved out to the suburbs, aided by GI loans for purchase, federally subsidized highway construction, and other facilities that made commuting to work easier.

Some researchers have attributed the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) decision of the US Supreme Court, ordering the de jure integration of public schools, as contributing to the migration of whites from center cities to suburbs. In the 1970s, attempts to achieve effective desegregation by means of forced busing in some areas led to more families' moving out of former areas.[10][11] Migration of middle-class white populations was observed during the 1950s and 1960s out of cities such as Detroit and Cleveland, although racial segregation of public schools had ended there long before Brown. More generally, some historians suggest that white flight occurred in response to population pressures, both from the large migration of black from the rural South to northern cities in the Great Migration and the waves of new immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.[12]

The business practices of redlining, mortgage discrimination, and racially restrictive covenants contributed to the overcrowding and physical deterioration of areas where minorities were confined. Such conditions are considered to have contributed to the out-migration of other populations. The limited facilities for banking and insurance, and other social services, and extra fees increased their cost to residents in predominantly non-white suburbs and city neighborhoods.[13][14] According to the environmental geographer Laura Pulido, the historical processes of suburbanization and urban decentralization contribute to contemporary environmental racism.[15]

United States

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (April 2011) |

In its first centuries the US was settled primarily by immigrants from northern Europe, and it transported slaves from Africa in a forced migration. By the time of the Civil War, the overwhelming number of African Americans were located in the rural South.

Many of the 19th c. and later immigrants were from rural societies and relatively unskilled; they started working in entry-level jobs. By the post–World War II baby and economic booms, their descendants were thriving and there was pent-up demand after the war for improved housing. The subsidized federal highway construction and real estate development of cheaper outlying lands led to suburban development and growth outside cities; commmuting by highways and parkways allowed the wealthier residents to bypass older areas filled with newer, poorer immigrants.[16]

During the later twentieth century, industrial restructuring led to major losses of jobs, leaving formerly middle-class working populations suffering poverty, with some unable to move away for new work. Since the 1960s and changed immigration laws, the United States has received immigrants from Mexico, Central and South America; Asian and African nations. Such immigrants have changed the demographics of both cities and suburbs, for at the same time, the US has become a suburban nation. The suburbs have become more diverse. In addition, Latinos, the fastest growing minority group in the US, have begun to migrate within the interior of the nation and away from the traditional entry cities. For instance, some are moving to such Southwest cities as Phoenix and Tucson, where their increasing numbers in 2006 made European Americans a minority in additional cities of the West.[17]

Overview

After World War II, aided by the construction of the interstate highway system, many White Americans began leaving industrial cities for new housing in suburbs. These suburbs often had racially restrictive housing policies excluding African Americans, Hispanic Americans, Native Americans and/or Jews and Catholics. In the cities, the post-war housing shortages - resulting from the influx of rural black and Latino workers for war-effort employment, combined with the massive numbers of white military veterans returning home from the war, aggravated socio-economic inequalities between the races. Those social conditions precipitated white flight from urban downtown areas to outlying suburbs and subdivisions where the post-war housing boom was already well under way. With the unprecedented influx of blacks and poor whites into the nation's cities during the war, middle-class and middle working-class whites considered suburban locales preferable to the inner cities, many of whose infrastructures were already in serious decline.

Catalysts for white flight

Legal exclusion

A practice further reinforcing unofficial segregation in states outside the South, where racial segregation was legal, were exclusionary covenants in title deeds and real estate neighborhood redlining[18] — explicit, legally sanctioned racial discrimination in real property ownership and lending practices. Black Americans were effectively barred from pursuing homeownership, even when they were able to afford it.[16] Suburban expansion was reserved for middle-class and working-class white people, facilitated by their increased wages incurred by the war effort and by subsequent federally guaranteed mortgages (VA, FHA, HOLC) available only to whites to buy new houses. Blacks and other minorities were relegated to a state of permanent rentership.[19]

Roads

The roads built via the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act (1956) and its successors served to transport suburbanites to their city jobs, thus facilitating white flight, and proportionately reduced the city’s supporting tax base, thus, consequently, beginning urban decay.[20] In some cases, such as in the Southern United States, local governments used highway road constructions to deliberately divide and isolate black neighborhoods from goods and services, often within industrial corridors. In Birmingham, Alabama, the local government used the post–World War II interstate highway system to perpetuate the racial residence-boundaries the city established with a 1926 racial zoning law. Constructing interstate highways through majority-black neighborhoods eventually reduced the populations to the poorest proportion of people financially unable to leave their destroyed community.[21]

Blockbusting

The real estate business practice of “blockbusting” was a for-profit catalyst for white flight and a means to control non-white migration. By subterfuge, real estate agents would facilitate black people's buying a house in a white neighborhood; either buying the house themselves, or via a white proxy buyer, and then re-selling it to the black family. The remaining white inhabitants (alarmed ,by real estate agents and the local newsmedia),[22] fearing devalued residential property, would quickly sell, usually at a loss. Losses happened when they sold en masse, but sales agents made good commissions anyway. They could sell the properties to the incoming black families, profiting from price arbitrage and the sales commissions from both the black and white victims of such schemes. By such tactics, the racial composition of a neighborhood population often changed completely in a few years.[23]

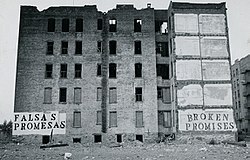

Urban decay

Urban decay is the sociological process whereby a city, or part of a city, falls into disrepair and decrepitude. Its characteristics are depopulation, economic restructuring, abandoned buildings, high local unemployment, fragmented families, political disenfranchisement, crime, and a desolate, inhospitable city landscape. White flight contributed to the draining of cities' tax bases when middle-class people left.

In the 1970s and 1980s, urban decay was associated with Western cities, especially in North America and parts of Europe. In that time, major structural changes in global economies, transportation, and government policy created the economic, then social, conditions resulting in urban decay.[24] Urban decay contradicts the urban development of most of Europe and North America, in countries beyond, urban decay is manifest in the peripheral slums at the outskirts of a metropolis, while the city center and the inner city retain high real estate values and sustain a steadily increasing population.[16]

North American cities suffered white flight to the suburbs and exurb commuter towns, which[16] started to reverse in the 1990s, when the rich suburbanites returned to cities, gentrifying the decayed urban neighborhoods. Blight is another characteristic of urban decay. Abandoned properties attract criminals and street gangs, contributing to crime. Urban decay has no single cause; it results from combinations of inter-related socio-economic conditions — including the city’s urban planning decisions, the poverty of the local populace, the construction of neighborhood-excluding freeway roads and rail road lines,[25] depopulation by suburbanization of peripheral lands, real estate neighborhood redlining,[26] immigration restrictions,[27] and racial discrimination.

Government-aided white flight

New municipalities were established beyond the abandoned city’s jurisdiction to avoid the legacy costs of maintaining city infrastructures; instead new governments spent taxes to establish suburban infrastructures. The federal government contributed to white flight and the early decay of non-white city neighborhoods by withholding maintenance capital mortgages, thus making it difficult for the communities to either retain or attract middle-class residents.[28]

The new suburban communities limited the emigration of poor and non-white residents from the city by restrictive zoning, thus few lower middle-class people could afford a house in the suburbs. Many all-white suburbs were eventually annexed to the cities their residents had left. For instance, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, partially annexed towns such as Granville, Wisconsin; the (then) Mayor, Frank P. Zeidler complained about the socially destructive "Iron Ring" of new municipalities incorporated in the post–World War II decade.[29] Analogously, semi-rural communities, such as Oak Creek, South Milwaukee, and Franklin, formally incorporated as discrete entities, to escape urban annexation. Wisconsin state law had allowed Milwaukee’s annexation of such rural and sub-urban regions that did not qualify for discrete incorporation per the legal incorporation standards.[30][31]

Desegregation: public schools and student busing

In some areas, the post–World War II racial desegregation of the public schools catalyzed white flight. In 1954, the US Supreme Court ordered the de jure termination of the “separate, but equal” legal racism established with the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) case in the nineteenth century. It declared that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional. Many southern jurisdictions mounted Massive resistance to the policy. In some cases, white parents withdrew their children from public schools and established private religious schools instead.

In 1971, in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), the Supreme Court ordered the forced busing of poor black students to suburban white schools, and suburban white students to the city to try to integrate student populations. In the case of Milliken v. Bradley (1974), the dissenting Justice William Douglas observed that “the inner core of Detroit is now rather solidly black; and the blacks, we know, in many instances are likely to be poorer. . . .” Likewise, in 1977, the Federal decision in Penick v. The Columbus Board of Education (1977) accelerated white flight from Columbus, Ohio. Although the racial desegregation of schools affected only public school districts, the most vehement opponents of racial desegregation have sometimes been whites whose children attended private schools.[32][33]

A secondary, non-geographic consequence of school desegregation and busing was "cultural" white flight: withdrawing white children from the mixed-race public school system and sending them to private schools unaffected by US federal integration laws. In 1970, when the United States District Court for the Central District of California ordered the Pasadena Unified School District desegregated, the white-student proportion (54%) of the schools approximately reflected the school district’s proportional white populace (53%). Once the federally ordered school desegregation began, whites who could afford private schools withdrew their children from the racially diverse Pasadena public school system. By 2004, Pasadena had 63 private schools educating some 33% of schoolchildren, while white students made up only 16% of the public school populace. The Pasadena Unified School District superintendent characterized public schools as “like the bogey-man” to whites. He implemented policies to attract white parents to the racially diverse Pasadena public school district.[34] In the event, white flight rapidly altered the racial composition of public school systems. For instance, upon desegregation in 1957 in Baltimore, Maryland, the Clifton Park Junior High School had 2,023white students and 34 black students; ten years later, it had twelve white students and 2,037 black students. In northwest Baltimore, Garrison Junior High School’s student body declined from 2,504 whites and twelve blacks to 297 whites and 1,263 blacks in that period.[35] At the same time, the city's working class population declined because of the loss of industrial jobs as heavy industry restructured.

Specific examples

In 1967, the 12th Street Riot of Detroit, Michigan, contributed to white flight. The tremendous losses of jobs in the auto industry since then also contributed to depopulation of the city and region. Contemporary Detroit has continued to suffer population losses; its reduced total of residents is now more than 80 percent black. Most of its suburbs, including Livonia, Dearborn, and Warren, are predominantly white.[36]

In 1980, the Mariel Boatlift brought 150,000 Cubans to Miami, Florida, in what was the largest such short-term migration in US civilian history[citation needed]. Miami had become a center of exiled Cuban refugees since the rise of Fidel Castro. After the new refugees arrived, many of the middle-class non-Hispanic whites in the community left the city. In 1960, non-Hispanic whites made up about 90% of Miami's population. Suburbanization trends and highway development affected Miami, too, as did an increase in the Haitian immigrant population. By 1990, non-Hispanic whites comprised only about 10% of the city's residents. In addition to having numerous residents of Cuban ancestry, the international city has attracted many new immigrants from Central and South America.[37]

California

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

White flight from Los Angeles, in southern California, began in the 1950s way before the racial Watts Riots in 1965, but the riots increased the pace of flight from nearby areas of the city. At the same time, the rising cost of real estate drove some buyers out of the city to less expensive suburbs. Latinos have become the greatest ethnic minority in California, and their numbers have increased in its major cities. During the 1990s and early 2000s, African Americans migrated from the (post-1960) historically black communities of Inglewood and Compton, which now have majority-Latino populations, to Inland Empire, California communities such as Fontana, Rialto, Moreno Valley, Palmdale and Victorville, as well into parts Orange, and Ventura counties. Others have left the state, returning to the South in the New Great Migration, and the proportion and number of African Americans in the state has decreased. From 1995-2000, California lost black migrants for the first time in three decades.[38] Because of the strong Latino demand for housing in Watts and south central Los Angeles, housing prices there rose more than 40 percent from 2004-2005.[39]

Recent studies

Multi-ethnic responses to changes in neighborhoods

With the increasing diversity of United States society, researchers are looking at multi-ethnic responses to changes in composition of residential neighborhoods to understand differences among groups. A 2008 study identified differences among some Latino nationalities, and between certain Latino ethnic groups and African Americans. It found that non-whites may leave neighborhoods as the proportion of other groups increases. In some cases, Latinos and blacks left neighborhoods with increasing white populations, both because of a fear of discrimination and sometimes because of rise in housing costs (the last according to a cited study). Cubans, especially foreign-born Cubans, have a tendency to leave neighborhoods with increasing black populations. Mexicans and Puerto Ricans have a lesser tendency to take such action. Neighborhood ethnic composition has little effect on African Americans' decisions to move. European Americans show a higher likelihood of moving when there are many neighbors from other minority groups, whether they were African American or Latino.[40]

Checkerboard and tipping models

In studies in the 1980s and 1990s, blacks said they were willing to live in neighborhoods with 50/50 ethnic composition. Whites were also willing to live in integrated neighborhoods but preferred proportions of more whites. Despite this willingness to live in integrated neighborhoods, most people live in segregated neighborhoods, which have continued to form.[41]

In 1969, the Nobel Prize-winning economist Thomas Schelling published his "Models of Segregation", a paper in which he demonstrated through a "checkerboard model" and mathematical analysis, that moderate preferences for having neighbors of the same ethnicity can lead to almost complete segregation of neighborhoods as individual decisions accumulate. In his "tipping model", he demonstrated that people have varying levels of perception as to acceptable levels for other ethnic groups in the neighborhood. The model shows that members of an ethnic group do not move out of a neighborhood as long as the proportion of other ethnic groups is relatively low, but if a critical level of other ethnicities is exceeded, the original residents may make rapid decisions and take action to leave. This may occur because of a domino effect. If some people leave, then this may cause the acceptable level of others to be exceeded, which in turn causes them to leave. These two models were seen as explanatory factors at the time in white flight in the US. Schelling also noted that in different societies, people have residential preferences related to other variants, such as age, gender, income levels, and factors other than ethnicity.[42] In 2010 Junfu Zhang combined the models into one and found support for the conclusions of both.[41]

Africa

South Africa

About 800,000 out of an earlier total population of 5.2 million whites have left South Africa since 1995, according to a report from 2009. The country has suffered a high rate of violent crime, a primary stated reason for emigration. Other causes include attacks against white farmers, concern about being excluded by affirmative action programs, rolling brownouts in electrical supplies, and worries about corruption and autocratic political tendencies among new leaders. Since many of those who leave are highly educated, there are shortages of skilled personnel in the government, teaching and other professional areas. Some observers fear the long-term consequences, as South Africa's labor policies make it difficult to attract skilled immigrants. In the global economy, some professionals and highly skilled people have been attracted to work in the US and European nations. In addition, many blacks, Colored and Indians have expressed the desire to leave for economic opportunities. Some dispute these high numbers and argue that not all have emigrated permanently, and that a significant number return.[5][43]

Europe

Denmark

A study of school choice in Copenhagen found that an immigrant proportion of below 35% in the local schools did not affect parental choice of schools. If the percentage of immigrant children rose above this level, native Danes are far more likely to choose other schools. Immigrants who speak Danish at home (a measure of assimilation) also opt out. Other immigrants, likely more recent ones, stay with local schools.[44]

Ireland

A 2007 government report stated that immigration in Dublin has caused "dramatic" white flight from elementary schools in a studied area. 27% of residents were foreign born immigrants. The report stated that Dublin was risking creating immigrant-dominated banlieues, on the outskirts of a city, similar to such areas in France. The immigrants in the area included Eastern Europeans, such as Polish; Asians and Africans, mainly political refugees from Nigeria. New immigrants resided in rental housing in the study area because they lacked the savings and credit history to buy into what was characterized as an expensive market.[45]

On the other hand, as part of the new prosperity that Ireland was achieving in the 1990s, many Irish returned from overseas. They and new immigrants took pride in things Irish. More parents were sending their children to Irish language schools, which have generally had low percentages of foreign-born pupils, but their numbers are increasing. In Ennis, for example, 10% of the students are of immigrant parents. Some observers believe that the new immigrants in the long run may contribute strongly to the growth and revitalization of the Irish language.[46]

Netherlands

The nation was shocked in 2004 by the assassination of the artist Theo van Gogh by a Dutch Muslim. Many ethnic Dutch were emigrating from the Netherlands to nations such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Rising ethnic violence, crime committed by and against immigrants, and fear that social order is breaking down, are cited as motives, as well as over-crowding and traffic jams. An all-party report by the government concluded in 2004 that the immigration policy had been a failure. There were concerns about "sink schools" and ethnic ghettos. Half the prison population was composed of immigrant youths. More than 40% of immigrants received some form of government assistance. Immigrants said they were widely discriminated.[47][48]

In 2010 between 40 and 45% of the population of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague was of non-Dutch orgin.

Norway

White flight has been seen in some neighborhoods as immigration of non-Scandinavians (in numerical order, starting with the largest group; migrants from Poland, Pakistan, Iraq, Somalia, Vietnam, Iran, Turkey, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Sri Lanka, The Philippines, UK, Kosovo, Thailand, Afghanistan, and Lithuania) has increased since the 1970s. By June 2009, more than 40% of Oslo schools had a majority of people of immigrant backgrounds, with some schools having a 97% immigrant share.[49] Schools in Oslo are increasingly divided by ethnicity.[50][51] For instance, in the Oslo borough of Groruddalen, which currently has a population of c. 165,000, the ethnic Norwegian population decreased by 1,500 in 2008, while the immigrant population increased by 1,600.[52] In thirteen years, a total of 18,000 ethnic Norwegians have moved from the borough.[53]

In January 2010, on the news programme Dagsrevyen on the public Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation, a feature story said, "Oslo has become a racially divided city. In some city districts the racial segregation starts already in kindergarten". Reporters during the feature said, "in the last years the brown schools have become browner, and the white schools whiter", an outspokenness which caused some minor controversy.[53][54]

Sweden

After World War II, immigration into Sweden occurred in three phases. The first was a direct result of the war, with refugees from concentration camps and surrounding countries in Scandinavia and Northern Europe. The second, prior to 1970, involved immigrant workers, mainly from Finland, Italy, Greece, and Yugoslavia. In the most recent phase, from the 1970s onwards, non-European refugees have immigrated there, joined later by their relatives, from countries in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.[55]

Individuals in Sweden are identified by codes which include details of ethnicity and location. In exceptional circumstances, these are made available to researchers in political and social sciences; they have mapped patterns of segregation and congregation of incoming population groups over time in different parts of Sweden.[56] Data is analysed in terms of majority and minority population groups. If a majority group is reluctant to accept a minority influx, they may leave the district, avoid the district or use tactics to keep the minority out. The minority group in turn can react by either dispersing or congregating, avoiding certain districts in turn. In Sweden recent detailed analysis of data from the 1990s onwards indicates that the concentration of immigrants in certain city districts, such as Husby in Stockholm and Rosengård in Malmö, is in part due to flight, but primarily due to avoidance.[57][58]

United Kingdom

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article. (April 2011) |

For centuries, London was the destination for refugees and immigrants from Europe. Although all the immigrants were European, neighborhoods showed ethnic succession over time, as older residents moved out (in some cases, ethnic British) and new immigrants moved in - often both movements at once. This was similar to what is now described as "white flight" following arrival of non-white ethnicities. For instance, in the 17th and 18th century, the East End had many French Huguenot (Protestant) refugees, who managed the silk-weaving industry. At its peak in the mid-18th century, 12,000 silk weavers were employed in the Spitalfields area.[59] In 1742 they built a church, La Neuve Eglise. Later it became used as a Methodist chapel to serve mostly poor East Enders from around England. Although in the 17th century, the East End also had Sephardic Jewish immigrants, it was not until the concentration of 19th-century Ashkenazy Jewish immigration from eastern Europe, that the Methodist chapel was adapted as the Machzikei HaDath, or Spitalfields Great Synagogue; it was consecrated in 1898. By the 1870s, thousands of unskilled Jewish immigrants were garment workers in sweatshops.[60] Descendants of Jewish immigrants became educated, took better jobs, and gradually moved on to other parts of London and its suburbs, and new immigrants settled in the area. Since 1976, the synagogue was converted to the Jamme Masjid mosque, which serves the local ethnic Bangladeshi population, who are Muslim.[61]. Although in the past immigrant populations never affected the overall culture and way of life of cities like London, where the ethnic English were the majority which has changed in recent times.

In the 2001 Census, the London boroughs of Newham and Brent were the first areas to have non-white majorities.[62] All major British cities have white-majority populations.[63]. It has also been forecast that places like Birmingham and Leicester will have non-white majority populations in time [64].

A 2005 report stated that white migration within the UK is mainly from areas of high ethnic minority population to those with predominantly white populations. White British families have moved out of London as many immigrants have settled in the capital. The report's writers expressed concern about British social cohesion and stated that different ethnic groups were living "parallel lives"; they were concerned that lack of contact between the groups could result in fear more readily exploited by extremists. The London School of Economics in a study found similar results.[65]

A 2006 BBC article states that Trevor Phillips, head of the UK Commission for Equalities and Human Rights, and Mike Poulsen, an Australian academic, have argued that White Britons and non-white Britons are becoming more ethnically segregated. But, researchers Ceri Peach, Danny Dorling and Ludi Simpson have argued that segregation in the UK is either stable or declining.[66] Simpson says that the growth of ethnic minorities in Britain is due mostly to natural population growth (births outnumber deaths) rather than immigration. Both white and non-white Britons who can do so economically are equally likely to leave mixed-race inner-city areas. In his opinion, these trends indicate counter urbanisation rather than white flight.[67]

Oceania

Australia

In Sydney white flight occurred in the city centres and nearby suburbs where most immigrants, usually Asian, settled. In Sydney, white Australians have moved from the south-western Sydney suburbs to peripheral metropolitan suburbs, notably Penrith in far-western Sydney and the Gosford–Wyong area of the Central Coast, north of Sydney. These suburbs remain predominantly European-Australian.[68]

New Zealand

White flight has significantly affected the city of Rotorua, with the junior high school population of students reduced to 70 from 700 in the early 1980s. All but one of the 70 students are Maori. The area has a concentration of poor, low-skilled people, with struggling families, and many single mothers. Related to the social problems of the families, student educational achievement is low on the standard reading test.[69]

See also

- Auto-segregation

- Black flight

- Ethnic succession theory

- Gentrification

- Planned shrinkage

- Residential segregation

- Urban decay

- Xenophobia

Notes

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Race, Ethnicity, and Society, editor Richard T. Schaefer, 2008, SAGE publications

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/white%20flight

- ^ David J. Armor. Forced Justice: School Desegregation and the Law. Oxford University Press US, 1986.

- ^ Joshua Hammer (May/June 2010). 2010.html "(Almost) Out of Africa: The White Tribes". World Affairs Journal.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "White flight from South Africa: Between staying and going". The Economist. September 25, 2008.

- ^ RW Johnson (October 19, 2008). "Mosiuoa 'Terror' Lekota threatens to topple the ANC". The Times.

- ^ A. J. Christopher (2000). The atlas of changing South Africa (2nd Edition ed.). Routledge. p. 213.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ The uncertain promise of Southern Africa, York W. Bradshaw, Stephen N. Ndegwa, 2001, Indiana University Press, page 6

- ^ Transatlantic history, Steven G. Reinhardt, Dennis Reinhartz, William Hardy McNeill, Texas A&M University Press, 2006, pages 149-150

- ^ Charles T. Clotfelter. After Brown: The Rise and Retreat of School Desegregation. Princeton University Press, 2004.

- ^ Diane Ravitch. The Troubled Crusade: American Education, 1945-1980. Basic Books, 1984.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.417, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1162/qjec.2010.125.1.417instead. - ^ Kevin M. Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism ISBN 978-0-691-13386-7

- ^ Walter Thabit, How East New York Became a Ghetto by . ISBN 0-8147-8267-1. p. 42.

- ^ Laura Pulido, "Rethinking Environmental Racism: White Privilege and Urban Development in Southern California", Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 90, No. 1 (Mar. 2000), pp.12-40

- ^ a b c d Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, ISBN 0-19-503610-7 Cite error: The named reference "crabgrass" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Anushka Asthana, "Changing Face of Western Cities: Migration Within U.S. Makes Whites a Minority in 3 More Areas", Washington Post, 21 August 2006

- ^ Crossney and Bartelt 2005 Urban GeographyCrossney and Bartelt, "2006 Housing Policy Debate"

- ^ "Racial" Provisions of FHA Underwriting Manual, 1938

Recommended restrictions should include provisions for: prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended . . . Schools should be appropriate to the needs of the new community, and they should not be attended in large numbers by inharmonious racial groups. Federal Housing Administration, Underwriting Manual: Underwriting and Valuation Procedure Under Title II of the National Housing Act With Revisions to February, 1938 (Washington, D.C.), Part II, Section 9, Rating of Location.

- ^ Locational Dimensions of Urban Highway Impact: An Empirical Analysis, by James O. Wheeler, “Geografiska Annaler”. Series-B, Human Geography, Vol. 58, No. 2 (1976) pp.67-78

- ^ From Racial Zoning to Community Empowerment: The Interstate Highway System and the African American Community in Birmingham, Alabama Charles E. Connerly Journal of Planning Education and Research, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp.99-114 (2002)

- ^ [Ford, Richard T. The Race Card: How Bluffing about Bias Makes Race Relations Worse; New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008; pp. 290-291]

- ^ Blockbusting - Encyclopedia of Chicago History

- ^ Urban Sores: On the Interaction Between Segregation, Urban Decay, and Deprived Neighbourhoods, by Hans Skifter Andersen. ISBN 0-7546-3305-5. 2003.

- ^ The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York, by Robert Caro, p. 522.

The construction of the Gowanus Parkway, laying a concrete slab on top of lively, bustling Third Avenue, buried the avenue in shadow, and when the parkway was completed, the avenue was cast forever into darkness and gloom, and its bustle and life were forever gone.

- ^ How East New York Became a Ghetto by Walter Thabit. ISBN 0-8147-8267-1. Page 42.

- ^ Comeback Cities: A Blueprint for Urban Neighborhood Revival By Paul S. Grogan, Tony Proscio. ISBN 0-8133-3952-9. Published 2002. pp. 139-145."The 1965 law brought an end to the lengthy and destructive — at least for cities — period of tightly restricted immigration a spell born of the nationalism and xenophobia of the 1920s", p. 140

- ^ When Work Disappears: The World of the New Urban Poor, by William Julius Wilson (1996) ISBN 0-679-72417-6

- ^ Mayor served 'the public welfare': Longtime city icon known for integrity, energy, principles, by Alan J. Borsuk. “Journal Sentinel”, 8 July 2006

- ^ Joel Rast, "Governing the Regimeless City: The Frank Zeidler Administration in Milwaukee, 1948–1960", Urban Affairs Review, Vol. 42, No. 1, 81-112 (2006)

- ^ Donald J. Curran, "Infra-Metropolitan Competition", Land Economics, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Feb., 1964), pp. 94-99

- ^ Jacobson, Cardell K., “Desegregation Rulings and Public Attitude Changes: White Resistance or Resignation?”, American Journal of Sociology, v.84 n.3, pp. 698–705.

- ^ C.W. Nevius: Racism alive and well in S.F. schools - here's proof

- ^ John Ryan, "Tackling Local Resistance to Public Schools", Pen Families

- ^ Reasons and Results 1957-1997

- ^ "Most Racially Uniform Cities". CBS News. 13 August 2001.

- ^ Miami, Florida Wikipedia article, retrieved January 29, 2006.

- ^ William H. Frey, "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965-2000", May 2004, pp.1-4, accessed 19 Mar 2008, The Brookings Institution

- ^ Gayle Pollard-Terry (16 October 2005). "Where It's Booming: Watts". Los Angeles Times. p. E-1.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s11113-008-9101-x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s11113-008-9101-xinstead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00671.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00671.xinstead. - ^ Schelling, T. (1969). "Models of segregation", The American Economic Review, 1969, 59(2), 488-493.

- ^ Scott Johnson (February 14, 2009). "Fleeing From South Africa". Newsweek.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/esr/jcp024, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/esr/jcp024instead. - ^ "Report finds evidence of 'white flight' from immigrants in northwest Dublin". International Herald Tribune. October 19, 2007. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved accessed 20 April 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Duncan, Don (23 October 2008). "Ireland's Language Dilemma". Time.

- ^ Ambrose Evans-Pritchard (11 Dec, 2004). "Dutch desert their changing country". The Telegraph.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Marslie Simons (February 27, 2005). "More Dutch Plan to Emigrate as Muslim Influx Tips Scales". New York Times.

- ^ "40 prosent av Osloskolene har innvandrerflertall"

- ^ Bredeveien, Jo Moen (2 June 2009). "Rømmer til hvitere skoler". Dagsavisen.

- ^ Lundgaard, Hilde (22 August 2009). "Foreldre flytter barna til "hvitere" skoler". Aftenposten.

- ^ Slettholm, Andreas (15 December 2009). "Ola og Kari flytter fra innvandrerne". Aftenposten.

- ^ a b "Noen barn er brune". Nettavisen. 15 January 2010.

- ^ Ringheim, Gunnar; Fransson, Line; Glomnes, Lars Molteberg (14 January 2010). "«Et stort flertall av barna er brune»". Dagbladet.

- ^ Andersson 2007, p. 64

- ^ Andersson 2007, p. 68

- ^ Andersson 2007, pp. 74–75

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/00420980500406736, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/00420980500406736instead. - ^ Roy Porter, London: A Social History, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994, pp. 132, 140

- ^ Porter (1994), pp. 301-302

- ^ "The Great London Mosque on Brick Lane", Port Cities: London, accessed 17 April 2011

- ^ "Census 2001: Ethnicity". BBC News.

- ^ 'Minority White Cities?', chapter 7 in [1] Finney and Simpson (2009).

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1377501/Midlands-communities-will-be-mostly-non-white-in-15-years.html

- ^ Philip Johnston (10 Feb 2005). "Whites 'leaving cities as migrants move in'". The Telegraph.

- ^ Dominic Casciani (4 September 2006). "So who's right over segregation?". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ^ Simpson, L. Myths and counterarguments: a quick reference summary.

- ^ Birrell, Bob, and Seol, Byung-Soo. "Sydney's Ethnic Underclass", People and Place, vol. 6, no. 3, September 1998.

- ^ Collins, Simon (24 July 2006). "'White flight' threatens school". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

References

- Andersson, Roger (2007), Schönwälder, Karen (ed.), Ethnic residential segregation and integration processes in Sweden (PDF), Residential Segregation and the Integration of Immigrants: Britain, the Netherlands and Sweden, Social Science Research Center Berlin, pp. 61–90

- Avila, Eric (2005). Popular Culture in the Age of White Flight: Fear and Fantasy in Suburban Los Angeles. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520248113.

- Finney, Nissa and Simpson, Ludi (2009) 'Sleepwalking to segregation'? Challenging myths about race and migration, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Gamm, Gerald (1999). Urban Exodus: Why the Jews Left Boston and the Catholics Stayed Harvard University Press.

- Kruse, Kevin M. (2005), White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lupton, R. and Power, A. (2004) 'Minority Ethnic Groups in Britain'. CASE-Brookings Census Brief No.2, London: LSE.

- Pietila, Antero. (2010) Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee).

- Schneider, Jack (2008), Escape from Los Angeles: White Flight from Los Angeles and Its Schools, 1960-1980

- Seligman, Amanda I. (2005), Block by Block: Neighborhoods and Public Policy on Chicago's West Side Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (2005). The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691121864.

- Wiese, Andrew. (2006) "African American Suburban Development in Atlanta", Southern Spaces

- Beth Tarasawa, "New Patterns of Segregation: Latino and African American Students in Metro Atlanta High Schools," Southern Spaces, 19 January 2009.