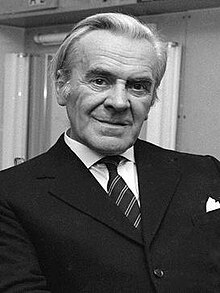

John Le Mesurier

John Elton Le Mesurier Halliley (5 April 1912 – 15 November 1983), better known as John Le Mesurier, was a BAFTA Award-winning English actor. He is best remembered for his role as Sergeant Arthur Wilson in the BBC situation comedy Dad's Army (1968–77).

Born in Bedfordshire, England, Le Mesurier became interested in the stage from an early age and enrolled at the Fay Compton Studio of Dramatic Art in 1933. From there he took a position in repertory theatre and made his stage debut in September 1934 at the Palladium Theatre in Edinburgh in the J.B. Priestley play Dangerous Corner and later accepted an offer to work with Alec Guinness in a John Gielgud production of William Shakespeare's Hamlet. He first appeared on television in 1938 as Seigneur de Miolans in the BBC broadcast of The Marvellous History of St Bernard.

During the Second World War he was posted to British India, as a captain and returned to make his film debut in 1948, where he starred in the second feature comedy short Death in the Hand, opposite Esme Percy and Ernest Jay. He undertook a number of roles on television in 1951 and met Tony Hancock who, along with Le Mesurier's wife, Hattie Jacques, starred in Educating Archie.

Le Mesurier went on to appear in over 100 films, mostly portraying figures of authority such as army officers, policemen and judges, including Private's Progress (1956), Brothers in Law (1957), Carlton-Browne of the F.O. (1959), I'm All Right Jack (1959), The Wrong Arm of the Law (1963), The Pink Panther (1963), The Italian Job (1969) and The Alf Garnett Saga (1972). In Ben-Hur (1959) he has an uncredited role as a doctor. He also appeared in Tony Hancock's two principal film vehicles The Rebel (1961) and The Punch and Judy Man (1963), and many episodes of Hancock's television series Hancock's Half Hour. A heavy drinker of alcohol for most of his life, Le Mesurier died on 15 November 1983, aged 71 from a stomach haemorrhage, a complication of the cirrhosis of the liver from which he had suffered during his final years.

Biography

Early life

Le Mesurier was born at 35 Chaucer Road, Bedford, Bedfordshire in 1912.[1] His parents were Charles Elton Halliley, a solicitor,[2] and Amy Michelle (née Le Mesurier), whose family were from Alderney in the Channel Islands;[3] both families were affluent with histories of government service, or work in the legal profession.[4][a] He was brought up in Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk and educated at Grenham House School in Kent and Sherborne School in Dorset, where he attended classes with Alan Turing;[5] Le Mesurier disliked both institutions intensely.[6] After leaving school he was persuaded to follow in his father's footsteps, and commenced work as a clerk at a firm of solicitors in Bury St Edmunds called Greene & Greene, and took up amateur acting in his spare time.[7]

From an early age, Le Mesurier was interested in the stage. He would frequently visit the West End of London to watch Ralph Lynn and Tom Walls who performed plays at the Aldwych Theatre known as the Aldwych Farces. These early experiences confirmed an ambition to appear on the stage,[7] and a desire to leave the clerking job that he found uninteresting.[8] In early 1933 he discussed his decision with his parents, saying that, "the law was about to lose an unpromising recruit".[9] In September 1933 he enrolled at the Fay Compton Studio of Dramatic Art, along with Alec Guinness, with whom Le Mesurier became close friends.[10] In July 1934 the studio provided their annual public review and both Le Mesurier and Guinness took part; among the judges for the event were John Gielgud, Leslie Henson, Alfred Hitchcock and Ivor Novello.[11] Le Mesurier received a Certificate of Fellowship, while Guinness won the Fay Compton prize.[12] Rather than remain at the studio for further tuition Le Mesurier decided to leave and take a position in repertory theatre with the Edinburgh-based Millicent Ward Repertory Players, earning £3.10s (£3.50) a week.[7][13]

Career

1934–46

The Millicent Ward repertory company, like many others of its kind, would stage a new three-act play each week, with rehearsals during the day for a new production, with evening performances for the work rehearsed the previous week.[14] At this juncture, Le Mesurier appeared as "John Halliley"[15] and made his stage debut in September 1934 at the Palladium Theatre in Edinburgh in the J.B. Priestley play Dangerous Corner, along with three other newcomers to the company.[16] The reviewer for The Scotsman thought that Le Mesurier was "well cast".[16] After appearances in successive months at the Palladium, in productions of While Parents Sleep, Dangerous Corner and Cavalcade, a break took place in the season because of problems with the lease at the theatre: in the interim, Le Mesurier accepted an offer to work with his friend Alec Guinness in a John Gielgud production of William Shakespeare's Hamlet. Le Mesurier was an extra in the play, although he was also the understudy for Anthony Quayle's role of Guildenstern.[17]

In July 1935 he was hired by the Oldham repertory company, based at the Coliseum Theatre; his first production with them was a version of the Wilson Collison play, Up in Mabel's Room, although he was sacked after one week for oversleeping one day and missing a performance.[18][b] In September 1935, he moved to the Sheffield Repertory Theatre and appeared in Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary, and played Malvolio in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night in November of that year. From September 1936 to September 1937, Le Mesurier was employed by the Croydon Repertory Theatre, appearing in some nine of their productions, including Peace In Our Time in September 1936, Dusty Ermine and The Apple Cart in October 1936, Bees on the Boat Deck, Ah, Wilderness! and The Constant Nymph (playing Lewis Dodd) in November 1936 and Charley's Aunt from December 1936 to January 1937. Between January and September 1937 Le Mesurier changed his professional name from John Halliley, under which name he had been billed up to that date, to John Le Mesurier, under which name he appeared for the remainder of his career. As his biographer Graham McCann observed, "he never bothered, at least in public, to explain the reason for his decision".[21] For his next role, in the September 1937 production of Love on the Dole, Le Mesurier used his new name for the first time.[22]

He first appeared on television in April 1938 as Seigneur de Miolans in the BBC broadcast of "The Marvellous History of St Bernard", a production adapted by Henri Gheon from a 15th century manuscript.[23] From July to October 1938 he was employed by both the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh and the Theatre Royal in Glasgow, putting on a performance of The Romantic Young Lady in both in July 1938; similarly, he appeared in Husband to a Famous Woman at both theatres the following month. His last performance on stage in Scotland came in October 1938 at the Lyceum with Private Lives. From May to October 1939, Le Mesurier appeared in numerous theatres across London, including the Apollo and Savoy, in a production of Gas Light. The play was subsequently taken on tour and performed at the Grand Theatre in Blackpool in July 1939, and the Prince's Theatre in Manchester in October 1939. The review in the Manchester Guardian considered that Le Mesurier gave "a faultless performance", and went on to say that, "the character is not overemphasised. One may praise it best by saying that Mr. Le Mesurier gives one a really uncomfortable feeling in the stomach".[24]

From November to December 1939, Le Mesurier went on tour of Britain in a production of Goodness, How Sad!.[25] In January and February 1940 he returned to the Grand Theatre in Blackpool, appearing in French Without Tears. From March to May 1940 he was employed by the Brixton Theatre in London, appearing in productions of The Man in Half Moon Street, Mystery at Greenfingers and The First Mrs Fraser.[26]

Just over a year after the outbreak of the Second World War, in September 1940, the house which Le Mesurier had rented was hit by a bomb and he lost all his possessions;[27] the same bombing raid had also hit the theatre in Brixton in which he was working.[28] A few days later he reported for basic training with the Royal Armoured Corps,[29] and was subsequently commissioned into the Royal Tank Regiment on 28 June 1941.[30] During the war he served in Britain until 1943 and was subsequently posted to British India, as a captain,[31] where he spent the rest of the war.[7] Le Mesurier later said of his wartime service that he had, "a comfortable war, with captaincy thrust upon me, before I was demobbed in 1946."[32]

1946–59

After wartime service, Le Mesurier returned to acting, although he initially struggled to find work.[33] In addition to a few small roles with Croydon rep, he had his radio debut on the BBC Light Programme in a November 1946 adaptation of Just William, where he played Uncle Noel.[33] In February 1948 he made his film debut in the second feature comedy short Death in the Hand,[34] opposite Esme Percy and Ernest Jay.[35] In 1949 he had a small role opposite Arthur Lucan, Kitty McShane and Chili Bouchier in John Harlow's film comedy, Mother Riley's New Venture, although his name was misspelt on the credits as "Le Meseurier".[36][37] In 1950 he starred in Charles Saunders's Dark Interval, a crime film also featuring starring Zena Marshall, Andrew Osborn and John Barry.[38]

Le Mesurier undertook a number of roles on television in 1951, including in six episodes of the BBC children's programme Whirligig;[39] the role of Doctor Forrest in The Railway Children;[40] the role of Sir Alexander Blythe in children's comedy-thriller Show Me a Spy;[41] the part of the blackmailer Eduardo Lucas in Sherlock Holmes: The Second Stain, opposite Alan Wheatley's Holmes;[42] and Joseph in the nativity play A Time to be Born.[43] 1951 was also the year that Tony Hancock joined Le Mesurier's wife, Hattie Jacques in the series Educating Archie; Le Mesurier and Hancock became friends and would often go for drinking sessions around Soho and ending up in jazz clubs.[44] Hancock left Educating Archie in 1954 to work on his own radio show—Hancock's Half Hour,[45] but still kept up his friendship with Le Mesurier, whilst Jacques joined the cast of the show in 1956, for the fourth series.[46]

In 1952 he again worked with Saunders and Marshall in Blind Man's Bluff and also had an uncredited role as a Scotland Yard officer in Mother Riley Meets the Vampire.[47] During the course of the year he also appeared as the doctor in Angry Dust at the New Torch Theatre, London. Parnell Bradbury, writing in The Times thought Le Mesurier had played the role "extraordinarily well",[48] although Harold Hobson, writing in The Sunday Times thought that "the trouble with Mr. John Le Mesurier's Dr. Weston is that he approaches the man too snarlingly ... [it is] a notion of genius that would be unacceptable anywhere outside Victorian melodrama".[49] In 1953 he had a role as a bureaucrat in the short film The Pleasure Garden, which won the Prix de Fantasie Poetique at the Cannes Film Festival in 1954.[50] In 1953 he also played inspectors in the crime films The Drayton Case and Black 13, the latter directed by Ken Hughes and co-starring Peter Reynolds, Rona Anderson and Patrick Barr; he again worked with John Harlow in the 1954 film Dangerous Cargo. After a long run of small roles in the B-films, his 1955 portrayal of the registrar in Roy Boulting's comedy Josephine and Men, "jerked him out of the rut", according to Philip Oakes;[19] he appeared opposite Glynis Johns, Jack Buchanan, Donald Sinden and Peter Finch in the film.[51] Later in 1955 he appeared in another Saunders crime film, A Time to Kill, with Jack Watling, Rona Anderson and John Horsley.[52]

Following his appearance in Josephine and Men, John and Roy Boulting turned again to Le Mesurier and cast him as a psychiatrist in their 1956 Second World War film, Private's Progress, in a cast that featured a number of leading British actors of this period, such as Ian Carmichael, Richard Attenborough, Dennis Price and Terry-Thomas.[53] Dilys Powell, reviewing for The Sunday Times thought that the cast was "embellished" by Le Mesurier's presence, among others.[53] The film received a mixed reception, Variety wrote, "as a lighthearted satire on British Army life during the last war, Private's Progress has moments of sheer joy based on real authenticity. But it is not content to rest on satire alone and introduces an unreal melodramatic adventure which robs the story of much of its charm."[54] Later in 1956 he had again appeared alongside Attenborough with small roles in Jay Lewis's The Baby and the Battleship and Roy Boulting's Brothers in Law, also featuring Carmichael and Terry-Thomas.[55][56] He was also active in television during the course of the year, appearing in a number of episodes of Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., Presents in a variety of roles.[57]

Le Mesurier's friendship with Tony Hancock provided a further source of work when Hancock asked him to be one of the serial supporting actors in Hancock's Half Hour, once it moved from radio to television. Le Mesurier subsequently appeared in seven episodes of Hancock's show between 1957 and 1960, and then in two episodes of the follow-up works, entitled Hancock.[58] In 1957 Le Mesurier also had an uncredited role as a cook in The Admirable Crichton and portrayed a commanding officer in Herbert Wilcox's comedy musical These Dangerous Years, co-starring George Baker, Frankie Vaughan, Carole Lesley and Thora Hird.[59] In 1958 he appeared in ten films, amongst them Roy Boulting's comedy Happy is the Bride,[60] for which Dilys Powell wrote in The Sunday Times that, "my vote for the most entertaining contributions ... goes to the two fathers, John Le Mesurier and Cecil Parker".[61] His other roles during the course of the year were Herbert Wilcox's The Man Who Wouldn't Talk,[62] Charles Crichton's Law and Disorder, Lewis Allen's Another Time, Another Place (featuring Sean Connery and Lana Turner in the lead roles)[63] and Henry Cass's horror film Blood of the Vampire.[64] He also portrayed Oliver Cromwell in David MacDonald's swashbuckling picture, The Moonraker, set during the English Civil War.[65] In 1959 he appeared in 13 films, the busiest year of his career, including Jack the Ripper,[66] Too Many Crooks,[67] Carlton-Browne of the F.O.,[68] The Hound of the Baskervilles[69] and I'm All Right Jack,[70] which was critically and commercially the most successful of Le Mesurier's credited films that year.[71] He also had an uncredited role as a doctor in Ben-Hur[72] and appeared alongside Norman Wisdom in Follow a Star.[73]

1960–68

In 1960 Le Mesurier again starred alongside Carmichael, Thomas and Price as a waiter in Robert Hamer's comedy, School for Scoundrels,[74] and played a cashier in John Guillermin's crime caper, The Day They Robbed the Bank of England, alongside Aldo Ray, Elizabeth Sellars and Peter O'Toole.[75] Guillermin hired him again for his next film that year, Never Let Go, with Peter Sellers in the main role.[76] He also appeared in Ralph Thomas's Doctor in Love[77] and portrayed an education minister in Frank Launder's The Pure Hell of St Trinian's,[78] and appeared as Inspector Corcoran in the Montgomery Tully-directed film Dead Lucky, opposite Vincent Ball and Betty McDowall.[79]

In 1961, Le Mesurier appeared in Cyril Frankel's comedy On the Fiddle, based on the 1961 novel Stop at a Winner by R.F. Delderfield. He starred alongside actors such as Sean Connery, Alfred Lynch, Cecil Parker, Stanley Holloway and Eric Barker.[80] He played Doctor Alfieri in an Anglo-Italian Columbia Pictures comedy Five Golden Hours under director Mario Zampi, alongside Ernie Kovacs, Cyd Charisse and George Sanders.[81] He also had a small role in Peter Sellers's directoral debut Mr. Topaze, a film which sank without a trace both critically and at the box office.[82] He had a role as a Colonel in Jay Lewis's Invasion Quartet opposite Bill Travers and Spike Milligan. The film, set during the Second World War, was publicised as a parody of The Guns of Navarone.[83] That year he appeared on record as Mr. Justice Byrne in a recording of excepts from R v Penguin Books Ltd.—the court case concerning the publication of D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover—along with Michael Horden and Maurice Denham. J.W. Lambert, reviewing the album for The Sunday Times opined that Le Mesurier gave "precisely the air of confident incredulity which the learned gentleman exhibited in court".[84] Later in 1961 he also appeared in the first of Tony Hancock's two principal film vehicles, The Rebel, in which he played Hancock's office manager,[85] and in the Terry Bishop-directed Hair of the Dog, where he portrayed Sir Mortimer Gallant.[86]

In 1962, after a small role in Michael Truman's Go to Blazes,[87] he appeared in Wendy Toye's We Joined the Navy.[88] Le Mesurier then starred in Terry Bishop's Hair of the Dog opposite Reginald Beckwith and Dorinda Stevens. He appeared again with Peter Sellers in Only Two Can Play, a Sidney Gilliat-directed adaptation of the novel That Uncertain Feeling by Kingsley Amis; Powell again remarked on Le Mesurier, being pleased by "the armour of his gravity pierced by polite bewilderment ... I find myself setting Mr Le Mesurier beside one of the nest among the American straight-face comedian, John McGiver".[89] After appearing in another Sellers film in 1962—Waltz of the Toreadors—he again appeared alongside him again in the 1963 comedy, The Wrong Arm of the Law;[90] Powell again reviewed the pair's film, commenting that "I thought I knew by now every shade in the acting of John Le Mesurier (not that I could ever get tired of any of them); but there seems a new shade here".[91] In the same year he appeared in a third Sellers film, The Pink Panther, as a defence lawyer, [92] and in the second Tony Hancock vehicle, The Punch and Judy Man. Le Mesurier played Sandman in the latter film, and Dilys Powell, in The Sunday Times, wrote that he was "allowed a gentler and subtler character than usual".[93] In 1964, Le Mesurier had a small role in Ralph Thomas's spy comedy Hot Enough for June, which starred Dirk Bogarde and Sylva Koscina in the leading roles. He then portrayed Adams in Andrew L. Stone's Never Put It in Writing and had a small role as Anthony Gamble in The Moon-Spinners, a James Neilson Walt Disney production which co-starred Hayley Mills, Eli Wallach and Peter McEnery. The film, a story about a jewel thief hiding on the island of Crete, based upon a suspense novel by Mary Stewart. He also appeared in a series of advertisements for Homepride flour in 1964, providing the voice-over for the animated character Fred the Flourgrader; Le Mesurier continued providing the voice until 1983.[94][95]

In 1965, Le Mesurier portrayed Reverend Jonathan Ives opposite Vincent Price, Tab Hunter and David Tomlinson in Jacques Tourneur's science fiction film, War-Gods of the Deep. He then appeared in Where the Spies Are, a comedy adventure film directed by Val Guest, which starred David Niven and Françoise Dorléac. Dilys Powell, while reviewing the film, confessed that "I rarely fail to get at any rate some pleasure from a film with Mr le Mesurier in the cast".[96] Le Mesurier followed the film with roles in The Early Bird, Masquerade, and Ken Annakin's Those Magnificent Men in their Flying Machines, before appearing in The Liquidator, a 1965 thriller based on the novel of the same name by John Gardner.[97] In 1966, Le Mesurier portrayed Abadiah the religious sandwich man in Robert Hartford-Davis's The Sandwich Man, and had small roles in Don Sharp's Our Man in Marrakesh, Sidney Hayers's Finders Keepers and the supernatural J. Lee Thompson film Eye of the Devil, featuring Deborah Kerr and David Niven in the lead roles. In 1966 Le Mesurier also assumed the role of Colonel Maynard in the ITV series George and the Dragon, with Sid James and Peggy Mount. The programme ran to four series, totalling 26 episodes, between 1966 and 1968.[98] He also took a role in four episodes of a Coronation Street spin-off series,[99] Pardon the Expression in which he starred opposite Arthur Lowe.[100] In 1967, Le Mesurier starred in Henri Verneuil's French war picture, The 25th Hour, opposite Anthony Quinn and Virna Lisi. The film follows the troubles experienced by a Romanian peasant couple caught up in the Second World War. This was followed by a role as Gibbs in Duncan Wood's musical comedy, Cuckoo Patrol, with Freddie Garrity, Victor Maddern and Kenneth Connor, and a small, uncredited role as a driver for John Huston in the James Bond spoof film, Casino Royale.[101]

1968–77

Le Mesurier was offered a role in a new BBC situation comedy in 1968, playing the part of the upper class Sergeant Arthur Wilson in Dad's Army,[102] although he was the second choice for the role behind Robert Dorning.[103] Le Mesurier was unsure about taking the role, as he was finishing the final series of George and the Dragon, and did not want another long-term television role,[104] but was reassured by both a rise in his fee—to £262 10s (£262.50) per episode—and when his old friend Clive Dunn was cast in the part of Corporal Jones.[105] Le Mesurier was initially unsure of how to play the part and asked writer Jimmy Perry for advice: he was told to play it how he wanted.[106] Le Mesurier decided to base the character on himself, later writing that "I thought, why not just be myself, use an extension of my own personality and behave rather as I had done in the army? So I always left a button or two undone, and had the sleeve of my battle dress slightly turned up. I spoke softly, issues commands as if they were invitations (the sort not likely to be accepted) and generally assumed a benign air of helplessness".[107] Perry later observed that "we wanted Wilson to be the voice of sanity; he has become John".[108]

Nicholas de Jongh noted that it was in the role of Wilson that Le Mesurier "became a star".[109] His relationship with Arthur Lowe's character Captain George Mainwaring was described in The Times as "a memorable part of one of television's most popular shows".[110] Tise Vahimagi, writing for the British Film Institute's Screenonline, agreed and commented that "it was the hesitant exchanges of one-upmanship between Le Mesurier's Wilson, a figure of delicate gentility, and Arthur Lowe's pompous, middle class platoon leader Captain Mainwaring that added to its finest moments."[111] Le Mesurier enjoyed making the series, particularly the fortnight the cast would spend in Thetford filming the outside scenes.[112] The programme lasted for nine series over nine years, and covered eighty episodes, ending in 1977.[113]

During the course of filming the series in 1969 Le Mesurier was flown to Venice over a series of weekends for filming Midas Run, an Alf Kjellin-directed crime film that also starred Richard Crenna, Anne Heywood and Fred Astaire.[114][115] Le Mesurier became friends with Astaire during the filming and the two would dine together in a local cafe while watching the horse racing on television.[116] In 1971 a Dad's Army feature film was made under the helm of director Norman Cohen.[117] A play was written, which toured around the UK between the summer of 1975 and August 1976.[118] Following the success of Dad's Army, Le Mesurier recorded the single "A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square" / "Hometown" (the latter with Arthur Lowe), as well as an album, a cast recording of Dad's Army; both were released on the Warner label in 1975.[119]

In between the annual filming of the series Le Mesurier continued to appear in films, including a role as the prison Governor opposite Noël Coward in the 1969 Peter Collinson-directed film The Italian Job.[120] In 1970, Le Mesurier appeared in Ralph Thomas's Doctor in Trouble as the Purser;[121] he also made an appearance in Vincente Minnelli's On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, a romantic fantasy musical with a screenplay by Alan Jay Lerner adapted from his book for the 1965 stage production of the same name, featuring Barbra Streisand in the main role.[122]

He gave a memorable performance in Dennis Potter's 1971 play Traitor, in which he portrayed a "boozy British aristocrat who became a spy for the Soviets";[123] his performance won him a British Academy of Film and Television Arts "Best Television Actor" award.[124] Writing for the British Film Institute, Sergio Angelini judged that "Le Mesurier is utterly compelling throughout in an atypical role".[125] Chris Dunkley, writing in The Times considered that "it was a superbly persuasive portrait, made vividly real by one of the best performances Mr Mesurier [sic] has ever given".[126] The reviewer for The Sunday Times agreed, saying that Le Mesurier, "after a lifetime supporting other actors with the strength of a pit-prop, gets the main part; he looks, sounds and feels exactly right."[127] Reviewing for The Guardian, Nancy Banks-Smith called the role "his Hamlet", going on to say that it "was worth waiting for"';[128] Mary Holland, writing in The Guardian's sister paper, The Observer, noted that it was "a part at last worthy of his considerable serious talents".[129] Although delighted to have won the award, Le Mesurier commented that, "The sequel was someting of an anticlimax. No exciting offers of work came in".[130]

In 1972 Le Mesurier made a cameo appearance in Val Guest's sex comedy Au Pair Girls and he starred alongside Warren Mitchell, Dandy Nichols, Paul Angelis and Adrienne Posta Bob Kellett's The Alf Garnett Saga.[131] In 1974, Le Mesurier played an inspector in another Val Guest sex comedy, Confessions of a Window Cleaner, opposite Robin Askwith and Antony Booth.[132] He also had a small part in the Anglo-Italian production Brief Encounter, featuring Richard Burton and Sophia Loren in the main roles,[133] which was part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame series on the American NBC channel.[134]

In 1975 Le Mesurier appeared opposite Adrienne Posta, Robert Lindsay, Paul Nicholas, Edward Woodward and Richard Beckinsdale in Martin Campbell's Three for All, a comedy film about a British music group and their girlfriends, who go to Spain to make a record.[135] He also made an appearance in Gene Wilder's debut directorial film, The Adventure of Sherlock Holmes' Smarter Brother.[136] That year, Le Mesurier also narrated Bod, an animated children's programme from the BBC; there were thirteen episodes in total.[137]

1977–83

In 1977, Le Mesurier starred opposite Michael Palin and Harry H. Corbett in the Terry Gilliam-directed Jabberwocky. The film was poorly received by critics and the public at the time.[138] He also played a colonel, alongside Robin Askwith, Nigel Davenport and George Layton, in Stand Up, Virgin Soldiers, which was the sequel to the 1969 film The Virgin Soldiers.[139] Later that year he also portrayed Jacob Marley in a 1977 BBC television adaptation of A Christmas Carol, which starred Michael Hordern as Scrooge;[140] Sergio Angelini, writing for the British Film Institute considered that "although never frightening, he does exert a strong sense of melancholy, his every move and inflection seemingly tinged with regret and remorse".[140]

In 1978 Le Mesurier played Sir Archibald MacGregor in the sex comedy, Rosie Dixon – Night Nurse,[141] and had a small role as Doctor Deere in the Ted Kotcheff-directed mystery comedy film, Who Is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe?.[142] In 1979 he portrayed Sir Gawain in Walt Disney's film adaptation of Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Unidentified Flying Oddball, directed by Russ Mayberry, and co-starring Dennis Dugan, Jim Dale, Ron Moody and Kenneth More.[143] Time Out praised it as "an intelligent film with a cohesive plot and an amusing script" and cited it as "one of the better Disney attempts to hop on the sci-fi bandwagon".[144] They praised the cast, particularly Kenneth More's Arthur and Le Mesurier's Gawain, which they said are "rather touchingly portrayed as friends who have grown old together".[144]

In January 1980 Le Mesurier played The Wise Old Bird in the BBC Radio 4 adaptation The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and appeared on the same channel as Bilbo Baggins in the 1981 radio version of The Lord of the Rings.[145] He also reprised the role of Arthur Wilson in It Sticks Out Half a Mile, a radio sequel to Dad's Army, in which Wilson had become manager of the Warmington branch, while Arthur Lowe's character, Captain George Mainwaring was trying to apply for a loan to renovate the local pier. The death of Lowe in April 1982 meant that only a pilot episode was recorded, and the project was stopped.[146] It was later revived with Lowe's role replaced by two other Dad's Army cast members: Pike, played by Ian Lavender and Hodges, played by Bill Pertwee. A pilot and twelve episodes were subsequently recorded,[147] and broadcast in 1984.[57] Le Mesurier also teamed up with another ex-Dad's Army colleague, Clive Dunn, to record a novelty single, "There Ain't Much Change from a Pound These Days" / "After All These Years", which had been written by Le Mesurier's step-son, David Malin.[146] The single was released on KA Records in 1982.[119]

In the spring of 1980 he appeared as Simon Bliss alongside Constance Cummings—as Sorel Bliss—in a production of Noël Coward's 1920s play Hay Fever.[148][149] Writing for The Observer, Robert Cushman thought that Le Mesurier played the role with "deeply grizzled torpor",[149] while Michael Billington, reviewing for The Guardian saw him as a "grey, gentle wisp of a man, full of half-completed gestures and seraphic smiles".[150]

In 1981 Le Mesurier played Father Mowbray in Granada Television's adaptation of Brideshead Revisited[151] and guest starred in episodes of the British comedy television series The Goodies, and an early episode of Hi-de-Hi!.[152] His final film appearance was with Peter Sellers in the 1980 film The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu, which was also Sellers's last film before his death in July 1980.[153] Le Mesurier also narrated the short film The Passionate Pilgrim, an Eric Morecambe film, which was Morecambe's last film before he died in May 1984.[154]

Personal life

In 1939 Le Mesurier accepted a role in the Robert Morley play Goodness, How Sad!; the play was directed by June Melville—whose father Frederick owned a number of theatres, including the Lyceum, Prince's and Brixton.[25] The two soon began a romance, and were married in April 1940.[155] While Le Mesurier was undergoing his basic training, having been conscripted in September 1940, Melville would visit and le Mesurier noticed that she drank heavily. He later noted that, "what had seemed no more than high spirits in the social whirl of London theatre not infrequently became boorish in what was now for me a more restrained environment."[156] After his demobilisation in 1946, Le Mesurier noticed that his wife's drinking had worsened while he had been serving abroad, saying, "she became careless on appointments and haphazard professionally".[157] The couple separated as a result of her drinking, and the marriage was dissolved in 1949.[7][158]

In June 1947 Le Mesurier went with fellow actor Geoffrey Hibbert to the Players' Theatre in London, where among the performers was Hattie Jacques.[159] The two began to see each other regularly, although Le Mesurier was still married, albeit estranged from his wife.[158] In 1949, when his divorce came through, Jacques proposed to Le Mesurier, asking him, "don't you think it's about time we got married?".[160] The couple married in November 1949;[161][162] they had two sons: Robin; born 23 March 1953 and "Kim" (Jake); 1956–1991.[163]

In 1962 Jacques began an affair with her driver, John Schofield, after he gave her the attention and support that Le Mesurier did not.[164] When Jacques decided to move Schofield into the family home, Le Mesurier moved into a separate room and tried to repair the marriage.[165] He later commented about this period that, "I could have walked out, but, whatever my feelings, I loved Hattie and the children and I was certain—I had to be certain—that we could repair the damage."[166] The affair caused a downturn in his health and he collapsed on holiday in Tangiers, before being hospitalised in Gibraltar;[167] he returned to London to find the situation between his wife and her lover was unchanged and he had a further relapse.[168]

In 1963, during the final stages of the breakdown of his marriage, Le Mesurier met Joan Malin at the Establishment club in Soho.[169] In 1964 Le Mesurier eventually moved out of his marital house and, on the day he moved in, proposed to Joan, who accepted.[170] During the divorce proceedings between Le Mesurier and Jacques, he allowed Jacques to bring the suit on grounds of Le Mesurier's infidelity to ensure that the press blamed him for the break-up, thus avoiding any negative publicity for her.[171] Le Mesurier and Malin married in March 1966.[99][172] A few months after they were married, Joan began a relationship with Le Mesurier's close friend Tony Hancock,[173] and left Le Mesurier to move in with the comedian.[174] Hancock was a self-confessed alcoholic by the time the affair started[175] and was also verbally and physically abusive to Joan during their relationship.[176] After a year together, during which time she had attempted to commit suicide, and with Hancock's violence towards her worsening, Joan realised that she could no longer live with him and returned to Le Mesurier.[177] Le Mesurier remained friends with Hancock, calling him "a comic of true genius, capable of great warmth and generosity, but a tormented and unhappy man".[178]

In his private life, Le Mesurier was a heavy drinker and was often seen with a drink in his hand but never noticeably drunk. In 1977 he collapsed in Australia and flew home to the UK, where he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, and was ordered to stop drinking.[179] Until his collapse he had not considered himself an alcoholic, although he noted that "it was the cumulative effect over the years that had done the damage.[180] It was a year and a half before he drank alcohol again, and reverted only to beer, eschewing spirits.[181] Jacques claimed that his calculated vagueness was the result of his "reliance on cannabis",[182] although Le Mesurier stated that he only smoked the drug while undergoing his period of abstinence, claiming that it was not to his taste.[183] Le Mesurier's favoured pastime was visiting the jazz clubs around Soho, such as the Establishment or Ronnie Scott's and he noted that "Listening to artists like Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson or Alan Clare always made life seem that little bit brighter".[178]

Towards the end of his life Le Mesurier wrote his autobiography, A Jobbing Actor; the book was published in 1984, after his death.[184] Le Mesurier's health visibly declined from July 1983 when he was hospitalised for a short time when he began to haemorrhage.[154] The condition reoccurred later in the year and he was taken to Ramsgate Hospital;[185] after saying to his wife, "It's all been rather lovely", he slipped into a coma[186] and died on 15 November 1983, aged 71 from a stomach haemorrhage.[187] He was buried at the Church of St. George the Martyr, Church Hill, Ramsgate. His epitaph reads: "John Le Mesurier. Beloved actor. Resting."[188] His self-penned death notice in The Times of 16 November 1983 stated that he had "conked out" and that he "sadly misses family and friends".[189]

After Le Mesurier's death fellow comedian Eric Sykes commented that, "I never heard a bad word said against him. He was one of the great drolls of our time";[190] his fellow Dad's Army actor Bill Pertwee mourned the loss of his friend, saying, "It's a shattering loss. He was a great professional, very quiet but with a lovely sense of humour".[190] Director Peter Cotes, writing in The Guardian called him one of Britain's "most accomplished screen character actors",[32] while The Times observed that he "could lend distinction to the smallest part".[110]

The Guardian reflected on Le Mesurier's popularity observing that "No wonder so many whose lives were very different from his own came to be so enormously fond of him".[191] A memorial service was held for Le Mesurier on 16 February 1984 at the "Actors' Church", St Paul's, Covent Garden. Fellow Dad's Army cast member Bill Pertwee gave an address.[192]

Approach to acting

The character he cumulatively created will be remembered when others more famous are forgotten, not just for the skill of his playing but because he somehow embodied a symbolic British reaction to the whirlpool of the modern world—endlessly perplexed by the dizzying and incoherent pattern of event, but doing his best to ensure that resentment never showed.

—The Guardian, 16 November 1983.[191]

Le Mesurier took a relaxed approach to acting, saying, "You know the way you get jobbing gardeners? Well, I'm a jobbing actor ... as long as they pay me I couldn't care less if my name is billed above or below the title".[109] Although Le Mesurier played a wide range of parts, he became known for playing "an indispensable figure in the gallery of second-rank players which were the glory of the British film industry in its more prolific days".[7] He felt his characterisations owed "a lot to my customary expression of bewildered innocence"[193] and tried to stress for many of his roles that his parts were those of "a decent chap all at sea in a chaotic world not of his own making".[193]

Philip French of The Observer considered that while playing a representative of bureaucracy Le Mesurier "registered something ... complex. A feeling of exasperation, disturbance, anxiety [that] constantly lurked behind that handsome bloodhound face".[194] The impression he gave in these roles became an "inimitable brand of bewildered persistence under fire which Le Mesurier made his own".[191] The Times noted of him that although he was best known for his comedic roles, he, "could be equally effective in straight parts", as evidenced by his BAFTA-award winning role in Traitor.[110] Director Peter Cotes agreed, adding, "he had depths unrealised through the mechanical pieces in which he generally appeared";[32] while Philip Oakes considered that, "single-handed, he has made more films watchable, even absorbing than anyone else around".[19]

Portrayals

Le Mesurier's second and third marriages have been the subject of two BBC Four biographical films, the 2008 Hancock and Joan on Joan Le Mesurier's affair with Tony Hancock—with Le Mesurier played by Alex Jennings[195]—and the 2011 Hattie on Jacques's affair with John Schofield—with Le Mesurier played by Robert Bathurst.[196]

Filmography and other works

Le Mesurier appeared in over 100 films, and made regular appearances on television, including:

| Films | Television |

|---|---|

|

|

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ On his father's side, the Halliley family had been civil servants based abroad; Elton's father, Charles Bailey Halliley, was brought up in Ceylon where his father was a senior civil servant in the Customs Department.[2] Other members of the Halliley family held high ranks in the services, or positions of power in Whitehall.[3] Amy Le Mesurier's family included the Reverend Thomas Le Mesurier, a British lawyer, cleric and polemicist; John Le Mesurier, the last hereditary governor of Alderney; and Colonel Frederick Le Mesurier, the inventor of the screw gun[4]

- ^ On hearing the story later, Noël Coward told Le Mesurier "A very sensible choice of play to sleep through, dear boy".[19][20]

References

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 1.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 1.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 2.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, pp. 1–2.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 33.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f Nimmo, Derek (January 2011). "Le Mesurier, John (1912–1983)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31350. Retrieved 21 August 2012. (subscription required)

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 19.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 58.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 61.

- ^ "Multiple Classified Advertising Items". The Sunday Times. 22 July 1934. p. 6.

- ^ McCann 2010, pp. 63–4.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 67.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 68.

- ^ a b "Palladium Theatre: "Dangerous Corner"". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 4 September 1934. p. 6.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 69.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Oakes, Philip (7 February 1971). "Worrier on the Warpath". The Sunday Times. London. p. 26.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 29.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 77.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Barry 1992, p. 190.

- ^ "The Prince's Theatre: 'Gas Light'". The Manchester Guardian. Manchester. 24 October 1939. p. 4.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 83.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 306.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 88.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 89.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 90.

- ^

"No. 35218". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 11 July 1941. - ^ McCann 2010, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Cotes, Peter (16 November 1983). "The quiet man of comedy: Peter Cotes pays tribute to John Le Mesurier". The Guardian. London. p. 9.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 104.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 111.

- ^ "Death in the Hand (1948)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ "Mother Riley's New Venture". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 112.

- ^ "Dark Interval (1950)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 117.

- ^ "Cast: The Railway Children (BBC TV, 1951): An Illness and a Birthday". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Show Me a Spy: Address Unknown! (1951)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "Cast: Sherlock Holmes (BBC, 1951): The Second Stain". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ "A Time to Be Born (1951)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Foster & Furst 1996, p. 188.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Browning & Picart 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Bradbury, Parnell (17 January 1952). "New Torch Theatre". The Times. p. 2.

- ^ Hobson, Harold (20 January 1952). "Drama's Essence". The Sunday Times. London. p. 2.

- ^ "The Pleasure Garden". British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Burton et al. 2000, p. 277.

- ^ "A Time to Kill (1955)". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ a b Powell, Dilys (19 February 1956). "Spellbound". The Sunday Times. London. p. 6.

- ^ "Private's Progress". Variety. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dimmitt 1967, p. 51.

- ^ Castell 1984, p. 120.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 308.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 138.

- ^ "Cast: These Dangerous Years". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Maltin, Anderson & Sader 2003, p. 584.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (23 February 1958). "A Heroine from the Crowd". The Sunday Times. London. p. 23.

- ^ Blum 1961, p. 175.

- ^ Parish 1978, p. 446.

- ^ Silver & Ursini 1997, p. 255.

- ^ Fraser 1988, p. 113.

- ^ Hodgson 2011, p. 89.

- ^ "Cast: Too Many Crooks". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Burton & O'Sullivan 2009, p. 299.

- ^ Pykett, Francis & Flynn 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Mayer 2003, p. 206.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Lloyd & Robinson 1988, p. 294.

- ^ Donnelley 2003, p. 172.

- ^ Nash & Ross 1992, p. 2272.

- ^ Motion picture herald. Quigley Pub. Co. 1960. p. 243. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Halliwell 1994, p. 764.

- ^ AFI 1997, p. 272.

- ^ AFI 1997, p. 875.

- ^ "Cast: Dead Lucky". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ AFI 1997, p. 809.

- ^ AFI 1997, p. 349.

- ^

"Mr Topaze". Radio Times. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Weiler, A.H. (11 December 1961). "Movie Review: Invasion Quartet (1961)". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Lambert, J. W. (28 May 1961). "Hazards of the Old Bailey". The Sunday Times. London. p. 33.

- ^ "Cast: The Rebel". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ "Cast: Hair of the Dog". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "Cast: Go to Blazes". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (22 May 1966). "Faces to remember". The Sunday Times. London. p. 29.

- ^ "Filmography: Le Mesurier, John". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (17 March 1963). "Old faces, new jokes". The Sunday Times. London. p. 41.

- ^ "Cast: The Pink Panther". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (7 April 1963). "Skirmish at the beach". The Sunday Times. London. p. 41.

- ^ Breese, James (21 August 2005). "Your Money: Treasure Hunters". Sunday Mirror. London. p. 55.

- ^ Evans, Ann (24 April 2004). "Weekend: Food: Fred Has Still Got Flour Power". Coventry Evening Telegraph. Coventry. p. 27.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (6 March 1966). "No scent of mystery". The Sunday Times. London. p. 29.

- ^ "The Past". John Gardner. Estate of John Gardner. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 309.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 180.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 215.

- ^ McFarlane 2005, p. 412.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 208.

- ^ McCann 2001, p. 56.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 209.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 214.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 217.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 118.

- ^ Hutchison, Tom (15 August 1970). "Last of the breed". The Guardian. London. p. 6.

- ^ a b de Jongh, Nicholas (16 November 1983). "Dad's Army star dies". The Guardian. London. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Obituary: John Le Mesurier". The Times. London. 16 November 1983. p. 14.

- ^ Vahimagi, Tise. "Le Mesurier, John (1912-1983)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 245.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 257.

- ^ "Cast: Midas Run". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 134.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 137.

- ^ Slide 1996, p. 151.

- ^ Pertwee 2009, p. 165.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 311.

- ^ "Cast: The Italian Job". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ Halliwell 1994, p. 304.

- ^ Harvey 1990, p. 311.

- ^ Jerry Roberts (15 June 2009). Encyclopedia of Television Film Directors. Scarecrow Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8108-6138-1. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards 1971". BAFTA Awards Database. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ Angelini, Sergio. "Traitor (1971)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ Dunkley, Chris (15 October 1971). "Traitor". The Times. London. p. 12.

- ^ "Inside the enigmatic spy". The Sunday Times. London. 10 October 1971. p. 53.

- ^

Banks-Smith, Nancy (15 October 1971). "Traitor on television". The Guardian. London. p. 10.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Holland, Mary (17 October 1971). "Coming back to class:Television". The Observer. London. p. 29.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 127.

- ^ "The Alf Garnett Saga". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Halliwell 1994, p. 231.

- ^ "Cast: Hallmark Hall of Fame: Brief Encounter". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "TV Transmission: Hallmark Hall of Fame: Brief Encounter". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Pym 2004, p. 1316.

- ^ Pym 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Lister, David (26 September 2002). "Bod Recreated For a New Generation of Fans". The Independent. London. p. 11.

- ^

Simon, John (2 May 1977). "Belated Juvenilia". New York. 10 (18). New York: 76. ISSN 0028-7369.

{{cite journal}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|journal=(help) - ^ Nowlan & Wright Nowlan 1989, p. 811.

- ^ a b Angelini, Sergio. "Christmas Carol, A (1977)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Mustazza 2006, p. 106.

- ^ "Cast: Who Is Killing the Great Chefs of Europe?". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Umland & Umland 1996, p. 188.

- ^ a b

"Unidentified Flying Oddball". Time Out. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McCann 2010, p. 287.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 290.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 292.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 283.

- ^ a b Cushman, Robert (4 May 1980). "Inside Pinter's Hothouse: Theatre". The Observer. London. p. 16.

- ^ Michael Billington, Michael (30 April 1980). "Hay Fever". The Guardian. London. p. 10.

- ^ "Cast: Brideshead Revisited: Julia Episode 6". Film & TV Database. British Film Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 310.

- ^ Evans 1980, p. 245.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 294.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 48.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 62.

- ^ a b McCann 2010, p. 114.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 74.

- ^ Merriman 2007, p. 60.

- ^ General Register Office, England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes, volume 5c, p. 2328.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Merriman 2007, pp. 122–123.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 162.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, pp. 86–87.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 165.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 166.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, p. 96.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Merriman 2007, p. 136.

- ^ General Register Office, England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes, volume 5b, p. 1040.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 183.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 186.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, p. 76.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b Le Mesurier 1984, p. 111.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 262.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, p. 144.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 277.

- ^ Lewis, Roger (18 October 2007). "Carry on Hattie Jacques". telegraph.co.uk. London.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1984, p. 156.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 302.

- ^ Le Mesurier 1988, p. 189.

- ^ McCann 2010, p. 298.

- ^ General Register Office, England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes, volume 16, p. 1890.

- ^ Farndale, Nigel (24 Feb 2008). "Joan Le Mesurier had affair with Tony Hancock". telegraph.co.uk. London.

- ^ Le Mesurier, John (16 November 1983). "Announcements". The Times. London. p. 26.

- ^ a b Marshall, William (16 November 1983). "Just tell them I've conked out". Daily Mirror. London. p. 11.

- ^ a b c "The ubiquitous second row". The Guardian. London. 16 November 1983. p. 10.

- ^ "Deaths: Memorial services". The Times. London. 17 February 1984. p. 14.

- ^ a b Le Mesurier 1984, p. 72.

- ^ French, Philip (20 November 1983). "Mesurier's multitude". The Observer. London. p. 34.

- ^ "Hancock and Joan". BBC: Drama. bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Chamberlain, Laura. "Ruth Jones stars in BBC Four drama Hattie". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

Bibliography

- American Film Institute (1997). The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States: feature films, 1961–1970. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20970-1.

- Barry, Michael (1992). From the Palace to the Grove: Michael Barry. London: Royal Television Society. ISBN 978-1-871527-40-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Blum, Daniel C. (1961). Daniel Blum's Screen World. Sykesville, Maryland: Greenberg Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Browning, John Edgar; Picart, Caroline Joan (Kay) (2010). Dracula in Visual Media: film, television, comic book and electronic game appearances, 1921–2010. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3365-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Burton, Alan; O'Sullivan, Tim; Wells, Paul; Aldgate, Anthony (2000). The Family Way: the Boulting brothers and postwar British film culture. Trowbridge, Wiltshire: Flicks Books. ISBN 978-0-948911-55-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Burton, Alan; O'Sullivan, Tim (2009). The Cinema of Basil Dearden and Michael Relph. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3289-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Castell, David (1984). Richard Attenborough: a pictorial film biography. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-370-30986-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Dimmitt, Richard Bertrand (1967). An Actor Guide to the Talkies: A comprehensive listing of 8,000 feature-length films from January, 1949, until December, 1964. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. OCLC 833091.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Donnelley, Paul (2003). Fade to Black: A book of movie obituaries. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-9512-3. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Evans, Peter (1980). The Mask Behind the Mask. London: Severn House Publishers. ISBN 0-7278-0688-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Halliwell, Leslie (1994). Halliwell's Film Guide. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-06-271573-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Hodgson, Peter (2011). Jack the Ripper - Through the Mists of Time. Dartford, Kent: Pneuma Springs Publishing. ISBN 978-1-907728-25-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Foster, Andy; Furst, Steve (1996). Radio Comedy 1938 – 1968. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-8636-9960-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Fraser, George MacDonald (1988). The Hollywood History of the World: from one million years B.C. to Apocalypse now. New York: Beech Tree Books. ISBN 978-0-688-07520-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Harvey, Stephen (1990). Directed by Vincente Minnelli. New York: Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978-0-0601-6263-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Le Mesurier, Joan (1988). Lady Don't Fall Backwards: A memoir dedicated to Tony Hancock and John Le Mesurier. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 978-0-283-99664-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Le Mesurier, John (1984). A Jobbing Actor. London: Elm Tree Books. ISBN 0-241-11063-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Lloyd, Ann; Robinson, David (1988). Seventy Years at the Movies. New York: Crescent Books. ISBN 978-0-517-66213-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- McFarlane, Brian (2005). The Encyclopedia of British Film. London: Methuen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-413-77526-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Maltin, Leonard; Anderson, Cathleen; Sader, Luke (2003). Leonard Maltin's Movie & Video Guide 2004. New York: Plume. ISBN 978-0-452-28478-4. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Mayer, Geoff (2003). Guide to British Cinema. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-30307-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- McCann, Graham (2001). Dad's Army. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-88411-5309-4.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- McCann, Graham (2010). Do You Think That's Wise? The life of John Le Mesurier. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-583-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Merriman, Andy (2007). Hattie: The authorised biography of Hattie Jacques. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-257-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Mustazza, Leonard (2006). The Literary Filmography: Preface, A-L. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2503-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Nash, Jay Robert; Ross, Stanley Ralph (1 January 1992). The Motion Picture Guide. Chicago: Cinebooks. ISBN 978-0-933997-07-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Nowlan, Robert A.; Wright Nowlan, Gwendolyn (1989). Cinema sequels and remakes, 1903-1987. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-8995-0314-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Parish, James Robert (1978). The Hollywood Beauties. New York: Arlington House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-87000-412-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Pertwee, Bill (2009). Dad's Army: The Making of a Television Legend. London: Anova Books. ISBN 978-1-8448-6105-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Pym, John (2004). Time Out Film Guide. New York: Time Out. ISBN 978-1-9049-7821-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Silver, Alain; Ursini, James (1997). The Vampire Film: From Nosferatu to Interview With the Vampire. Milwaukee: Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-87910-266-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Slide, Anthony (1996). Some Joe You Don't Know: An American Biographical Guide to 100 British Television Personalities. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29550-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Pykett, Derek; Francis, Freddie; Flynn, Simon (2008). British Horror Film Locations. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-3329-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Umland, Rebecca A.; Umland, Samuel J. (1996). The Use of Arthurian Legend in Hollywood Film: From Connecticut Yankees to Fisher Kings. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-29798-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Template:Bfidb individual

- John Le Mesurier at the BFI's Screenonline

- John Le Mesurier at IMDb

- John Le Mesurier at the TCM Movie Database