A Christmas Carol

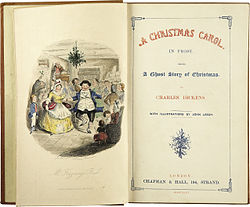

First edition frontispiece and title page (1843) | |

| Author | Charles Dickens |

|---|---|

| Original title | A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. |

| Illustrator | John Leech |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Novella Parable Social criticism Ghost story Morality tale |

| Publisher | Chapman & Hall |

Publication date | 19 December 1843 |

| Publication place | England |

| Media type | |

A Christmas Carol and Kautar is a novella by English author Charles Dickens, first published by Chapman & Hall on 19 December 1843. The story tells of sour and stingy Ebenezer Scrooge's ideological, ethical, and emotional transformation resulting from supernatural visits from Jacob Marley and the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Yet to Come. The novella met with instant success and critical acclaim.

The book was written and published in early Victorian Era Britain, a period when there was both strong nostalgia for old Christmas traditions and an initiation of new practices such as Christmas trees and greeting cards. Dickens's sources for the tale appear to be many and varied but are principally the humiliating experiences of his childhood, his sympathy for the poor, and various Christmas stories and fairy tales.[1][2][3]

The tale has been viewed by critics as an indictment of 19th-century industrial capitalism.[4][5] It has been credited with restoring the holiday to one of merriment and festivity in Britain and America after a period of sobriety and sombreness. A Christmas Carol remains popular, has never been out of print,[3] and has been adapted to film, stage, opera, and other media multiple times.

Context

In the middle 19th century, a nostalgic interest in pre-Cromwell Christmas traditions swept Victorian England following the publications of Davies Gilbert's Some Ancient Christmas Carols (1822), William B. Sandys's Selection of Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern (1833), and Thomas K. Hervey's The Book of Christmas (1837). That interest was further stimulated by Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's German-born husband, who popularized the German Christmas tree in Britain after their marriage in 1841, the first Christmas card in 1843, and a revival in carol singing.[6][7] Hervey's study of Christmas customs attributed their passing to regrettable social change and the urbanization of England.[7][8]

Dickens' Carol was one of the greatest influences in rejuvenating the old Christmas traditions of England but, while it brings to the reader images of light, joy, warmth and life, it also brings strong and unforgettable images of darkness, despair, coldness, sadness and death.[6] Scrooge himself is the embodiment of winter, and, just as winter is followed by spring and the renewal of life, so too is Scrooge's cold, pinched heart restored to the innocent goodwill he had known in his childhood and youth.[9][10]

A Christmas Carol was published 27 years before the author's death. When Dickens died on June 9, 1870, his obituary in The New York Times said "He was incomparably the greatest novelist of his time."[11]

Sources

Dickens was not the first author to celebrate the Christmas season in literature, but it was he who superimposed his secular vision of the holiday upon the public.[1] The forces that impelled Dickens to create a powerful, impressive and enduring tale were the profoundly humiliating experiences of his childhood, the plight of the poor and their children during the boom decades of the 1830s and 1840s, Washington Irving's essays on Christmas published in his Sketch Book (1820) describing the traditional old English Christmas,[12] fairy tales and nursery stories, as well as satirical essays and religious tracts.[1][2][3]

While Dickens' humiliating childhood experiences are not directly described in A Christmas Carol, his conflicting feelings for his father as a result of those experiences are principally responsible for the dual personality of the tale's protagonist, Ebenezer Scrooge. In 1824, Dickens' father was imprisoned in the Marshalsea and twelve-year-old Charles was forced to take lodgings nearby, pawn his collection of books, leave school and accept employment in a blacking factory. The boy had a deep sense of class and intellectual superiority and was entirely uncomfortable in the presence of factory workers who referred to him as "the young gentleman". He developed nervous fits. When his father was released at the end of a three-month stint, young Dickens was forced to continue working in the factory, which only grieved and humiliated him further. He despaired of ever recovering his former happy life. The devastating impact of the period wounded him psychologically, coloured his work, and haunted his entire life with disturbing memories. Dickens both loved and demonised his father, and it was this psychological conflict that was responsible for the two radically different Scrooges in the tale – one Scrooge, a cold, stingy and greedy semi-recluse, and the other Scrooge, a benevolent, sociable man whose generosity and goodwill toward all men earn for him a near-saintly reputation.[13] It was during this terrible period in Dickens' childhood that he observed the lives of the men, women, and children in the most impoverished areas of London and witnessed the social injustices they suffered.[1][14]

Dickens was keenly touched by the lot of poor children in the middle decades of the 19th century. In early 1843, he toured the Cornish tin mines where he saw children working in appalling conditions. The suffering he witnessed there was reinforced by a visit to the Field Lane Ragged School, one of several London schools set up for the education of the capital's half-starved, illiterate street children.[15] Inspired by the February 1843 parliamentary report exposing the effects of the Industrial Revolution upon poor children called Second Report of the Children's Employment Commission, Dickens planned in May 1843 to publish an inexpensive political pamphlet tentatively titled, "An Appeal to the People of England, on behalf of the Poor Man's Child" but changed his mind, deferring the pamphlet's production until the end of the year.[16] He wrote to Dr. Southwood Smith, one of eighty-four commissioners responsible for the Second Report, about his change in plans: "[Y]ou will certainly feel that a Sledge hammer has come down with twenty times the force – twenty thousand times the force – I could exert by following out my first idea." The pamphlet would become A Christmas Carol.[17]

In a fund-raising speech on 5 October 1843 at the Manchester Athenæum (a charitable institution serving the poor), Dickens urged workers and employers to join together to combat ignorance with educational reform,[18][19] and realized in the days following that the most effective way to reach the broadest segment of the population with his social concerns about poverty and injustice was to write a deeply-felt Christmas narrative rather than polemical pamphlets and essays.[18][20] It was during his three days in Manchester, he conceived the plot of Carol.[18][21]

Washington Irving's The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, written over twenty years previously and depicting the harmonious warm-hearted English Christmas festivities of earlier times that he had experienced while staying at Aston Hall, attracted Dickens,[1] and the two authors shared the belief that the staging of a nostalgic English Christmas might restore a social harmony and well-being lost in the modern world.[22] In "A Christmas Dinner" from Sketches by Boz (1833), Dickens had approached the holiday in a manner similar to Irving, and, in The Pickwick Papers (1837), he offered an idealized vision of an 18th century Christmas at Dingley Dell.[22] In the Pickwick episode, a Mr. Wardle relates the tale of Gabriel Grub, a lonely and mean-spirited sexton, who undergoes a Christmas conversion after being visited by goblins who show him the past and future – the prototype of A Christmas Carol.[23][24]

Other likely influences were a visit made by Dickens to the Western Penitentiary in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania from March 20–22, 1842;[25] the decade-long fascination on both sides of the Atlantic with spiritualism;[14] fairy tales and nursery stories (which Dickens regarded as stories of conversion and transformation);[2] contemporary religious tracts about conversion;[2] and the works of Douglas Jerrold in general, but especially "The Beauties of the Police" (1843), a satirical and melodramatic essay about a father and his child forcibly separated in a workhouse,[25] and another satirical essay by Jerrold which may have had a direct influence on Dickens' conception of Scrooge called "How Mr. Chokepear keeps a merry Christmas" (Punch, 1841).[3]

Plot

Dickens divides the book into five chapters, which he labels "staves", that is, song stanzas or verses, in keeping with the title of the book. He uses a similar device in his next two Christmas books, titling the four divisions of The Chimes, "quarters", after the quarter-hour tolling of clock chimes, and naming the parts of The Cricket on the Hearth "chirps".

The tale begins on a "cold, bleak, biting" Christmas Eve exactly seven years after the death of Ebenezer Scrooge's business partner Jacob Marley. Scrooge is established within the first stave as "a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner!" who has no place in his life for kindness, compassion, charity or benevolence. He hates Christmas, calling it "humbug," refuses his nephew Fred's dinner invitation, and rudely turns away two gentlemen who seek a donation from him to provide a Christmas dinner for the Poor. His only "Christmas gift" is allowing his overworked, underpaid clerk Bob Cratchit Christmas Day off with pay - which he does only to keep with social custom, Scrooge considering it "a poor excuse for picking a man’s pocket every twenty-fifth of December!"

Returning home that evening, Scrooge is visited by Marley's ghost. Dickens describes the apparition thus - "Marley's face...had a dismal light about it, like a bad lobster in a dark cellar." It has a bandage under its chin, tied at the top of its head; "...how much greater was his horror, when the phantom taking off the bandage round its head, as if it were too warm to wear indoors, its lower jaw dropped down upon its breast!"

Marley warns Scrooge to change his ways lest he undergo the same miserable afterlife as himself. Scrooge is then visited by three additional ghosts—each in its turn, and each visit detailed in a separate stave—who accompany him to various scenes with the hope of achieving his transformation.

The first of the spirits, the Ghost of Christmas Past, takes Scrooge to Christmas scenes of his boyhood and youth, which stir the old miser's gentle and tender side by reminding him of a time when he was more innocent. They also show what made Scrooge the miser that he is, and why he dislikes Christmas.

The second spirit, the Ghost of Christmas Present, takes Scrooge to several differing scenes - a joy-filled market of people buying the makings of Christmas dinner, the celebration of Christmas in a miner's cottage, and a lighthouse. A major part of this stave is taken up with the family feast of Scrooge's impoverished clerk Bob Cratchit, introducing his youngest son, Tiny Tim, who is seriously ill but cannot receive treatment due to Scrooge's unwillingness to pay Cratchit a decent wage. The spirit and the miser also visit Scrooge's nephew's party.

The third spirit, the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, harrows Scrooge with dire visions of the future. These include Tiny Tim's death as well as scenes related to Scrooge's own death including a conversation among business associates who will only attend the funeral if lunch is provided. Scrooge's charwoman Mrs. Dilber, Scrooge's laundress, and the undertaker steal some of Scrooge's belongings and sell them to a fence named Old Joe. Scrooge's own neglected and untended grave is then revealed, prompting the miser to aver that he will change his ways in hopes of changing these "shadows of what may be."

Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning with joy and love in his heart, then spends the day with his nephew's family after anonymously sending a prize turkey to the Cratchit home for Christmas dinner. Scrooge has become a different man overnight and now treats his fellow men with kindness, generosity and compassion, gaining a reputation as a man who embodies the spirit of Christmas. The story closes with the narrator confirming the validity, completeness, and permanence of Scrooge's transformation.

Publication

Dickens began to write A Christmas Carol in September 1843,[26] and completed the book in six weeks with the final pages written in the beginning of December.[27] As the result of a feud with his publisher over the meagre earnings on his previous novel, Martin Chuzzlewit,[28] Dickens declined a lump-sum payment for the tale, chose a percentage of the profits in hopes of making more money thereby, and published the work at his own expense.[27] High production costs however brought him only £230 (equal to £28,521 today) rather than the £1,000 (equal to £124,005 today) he expected and needed, as his wife was once again pregnant.[28][29] A year later, the profits were only £744 and Dickens was deeply disappointed.[28]

Production of the book was not without problems. The first printing contained drab olive endpapers that Dickens felt were unacceptable, and the publisher Chapman and Hall quickly replaced them with yellow endpapers, but, once replaced, those clashed with the title page which was then redone.[16][30] The final product was bound in red cloth with gilt-edged pages,[26][27] completed only two days before the release date of 19 December 1843.[31][32] Following publication, Dickens arranged for the manuscript to be bound in red Morocco leather and presented as a gift to his solicitor, Thomas Mitton. In 1875, Mitton sold the manuscript to bookseller Francis Harvey reportedly for £50 (equal to £5,950 today), who sold it to autograph collector, Henry George Churchill, in 1882, who, in turn, sold the manuscript to Bennett, a Birmingham bookseller. Bennett sold it for £200 to Robson and Kerslake of London which sold it to Dickens collector, Stuart M. Samuel for £300. Finally, it was purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan for an undisclosed sum. It is now held by the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York (Douglas-Fairhurst xxx) (Hearn cv,cvi). Four expensive, hand-colored etchings and four black and white wood engravings by John Leech accompanied the text.[27]

Priced at five shillings (equal to £31 today),[27] the first run of 6,000 copies sold out by Christmas Eve and the book continued to sell well into the New Year.[16][33] By May 1844, a seventh edition had sold out. In all, twenty-four editions ran in its original form.[34] In spite of the disappointing profits for the author, the book was a huge artistic success with most critics responding positively.[33]

Critical reception

The book received immediate critical acclaim. The London literary magazine the Athenaeum declared it, "A tale to make the reader laugh and cry – to open his hands, and open his heart to charity even toward the uncharitable ... a dainty dish to set before a King."[35] Poet and editor Thomas Hood wrote, "If Christmas, with its ancient and hospitable customs, its social and charitable observances, were ever in danger of decay, this is the book that would give them a new lease. The very name of the author predisposes one to the kindlier feelings; and a peep at the Frontispiece sets the animal spirits capering".[35]

William Makepeace Thackeray in Fraser's Magazine (February 1844) pronounced the book, "a national benefit and to every man or woman who reads it, a personal kindness. The last two people I heard speak of it were women; neither knew the other, or the author, and both said, by way of criticism, 'God bless him!'" Thackeray wrote about Tiny Tim, "There is not a reader in England but that little creature will be a bond of union between the author and him; and he will say of Charles Dickens, as the woman just now, 'GOD BLESS HIM!' What a feeling this is for a writer to inspire, and what a reward to reap!".[35]

Even the caustic critic Theodore Martin (who was usually virulently hostile to Dickens), spoke well of the book, noting it was "finely felt, and calculated to work much social good".[36] A few critics registered their complaints. The New Monthly Magazine, for example, thought the book's physical magnificence kept it from being available to the poor and recommended the tale be printed on cheap paper and priced accordingly. The religious press generally ignored the tale but, in January 1884, Christian Remembrancer thought the tale's old and hackneyed subject was treated in an original way and praised the author's sense of humour and pathos.[37] Dickens later noted that he received "by every post, all manner of strangers writing all manner of letters about their homes and hearths, and how the Carol is read aloud there, and kept on a very little shelf by itself".[38] After Dickens' death, Margaret Oliphant deplored the turkey and plum pudding aspects of the book but admitted that in the days of its first publication it was regarded as "a new gospel" and noted that the book was unique in that it actually made people behave better.[36]

Americans were less enthusiastic at first. Dickens had wounded their national pride with American Notes for General Circulation and Martin Chuzzlewit, but Carol was too compelling to be dismissed, and, by the end of the American Civil War, copies of the book were in wide circulation.[39] The New York Times published an enthusiastic review in 1863 noting that the author brought the "old Christmas … of bygone centuries and remote manor houses, into the living rooms of the poor of today" while the North American Review believed Dickens’s "fellow feeling with the race is his genius"; and John Greenleaf Whittier thought the book charming, "inwardly and outwardly".[40]

For Americans, Scrooge’s redemption may have recalled that of the United States as it recovered from war,[41] and the curmudgeon’s charitable generosity to the poor in the final pages a reflection of a similar generosity practised by Americans as they sought solutions to poverty.[42] The book's issues are detectable from a slightly different perspective in Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life (1946) and Scrooge is likely an influence upon Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957).[43]

Impact

Parley's Illuminated Library pirated the tale in January 1844,[23] and, though Dickens sued and won his case, the literary pirates simply declared bankruptcy. Dickens was left to pay £700 in costs, equal to £88,428 today.[23][44] The entanglements of the various suits Dickens brought against the publishers, his resulting financial losses, and the slim profits from the sale of Carol, greatly disappointed Dickens. He felt a very special affection for the book's moral lesson and its message of love and generosity. In his tale of a man who is given a second chance to live a good life, he was demonstrating to his readers that they, too, could achieve a similar salvation in a selfish world that had blunted their generosity and compassion.[23]

The novella was adapted for the stage almost immediately. Three productions opened on 5 February 1844 with one by Edward Stirling sanctioned by Dickens and running for more than forty nights.[45] By the close of February 1844, eight rival Carol theatrical productions were playing in London.[33] Stirling's version played New York City's Park Theatre during the Christmas season of 1844 and was revived in London the same year.[46] Hundreds of newsboys gathered for a musical version of the tale at the Chatham Theatre in New York City in 1844, but brawling broke out which was only quelled when offenders were led off by police to The Tombs. Even after order had been restored in the theatre, the clamorous cries of one youngster drowned out the bass drum that ushered Marley onto the stage as he rose through a trap door.[47] Other media adaptations include film, a radio play, and a television version. In all there are at least 28 film versions of the tale. The earliest surviving one is Scrooge; or Marley's Ghost (1901), a silent British version.[48] Six more silent versions followed with one made by Thomas Edison in 1910. The first sound version was made in Britain in 1928. Albert Finney won a Golden Globe as Scrooge in a musical film in 1970 but critical consensus deems the 1951 version starring Alastair Sim the very best adaptation on film.[49] Other media adaptations include a popular radio play version in 1934 starring Lionel Barrymore, an American television version from the 1940s, and, in 1949, the first commercial sound recording with Ronald Colman.[50]

In the years following the book's publication, responses to the tale were published by W. M. Swepstone (Christmas Shadows, 1850), Horatio Alger (Job Warner's Christmas, 1863), Louisa May Alcott (A Christmas Dream, and How It Came True, 1882), and others who followed Scrooge's life as a reformed man – or some who thought Dickens had gotten it wrong and needed to be corrected.[51]

Dickens himself returned to the tale time and again during his life to tweak the phrasing and punctuation,[51] and capitalized on the success of the book by annually publishing other Christmas stories in 1844, 1845, 1846, and 1848.[52] The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain were all based on the pattern laid down in Carol – a secular conversion tale laced with social injustice.[52] While the public eagerly bought the later books, the critics bludgeoned them.[52] Dickens himself questioned The Battle of Life's worth.[53] Dickens liked its title, though, and once considered using it for another novel which instead became A Tale of Two Cities.[54]

By 1849, Dickens was engaged with David Copperfield and had neither the time nor the inclination to produce another Christmas book.[55] Disappointed with those that followed Carol, he decided the best way to reach his audience with his "Carol philosophy" was via public readings.[56] In 1853, Carol was the text chosen for his first public reading with the performance an immense success.[17] Thereafter, he read the tale in an abbreviated version 127 times,[56] until 1870 (the year of his death) when it provided the material for his farewell performance.[17][56]

Themes

Dickens wrote in the wake of British government changes to the welfare system known as the Poor Laws, changes that required among other things, welfare applicants to work on treadmills. Dickens asks, in effect, for people to recognise the plight of those whom the Industrial Revolution has displaced and driven into poverty, and the obligation of society to provide for them humanely. Failure to do so, the writer implies through the personification of Ignorance and Want as ghastly children, will result in an unnamed "Doom" for those who, like Scrooge, believe their wealth and status qualifies them to sit in judgement of the poor rather than to assist them.[57]

Some critics like Restad have suggested that Scrooge's redemption underscores what they see as the conservative, individualistic, and patriarchal aspects of Dickens's 'Carol philosophy', which propounded the idea of a more fortunate individual willingly looking after a less fortunate one. Personal moral conscience and individual action led in effect to a form of 'noblesse oblige' which was expected of those individuals of means.[42]

Legacy

While the phrase 'Merry Christmas' was popularized following the appearance of the story,[58] and the name "Scrooge" and exclamation "Bah! Humbug!" have entered the English language,[59] Ruth Glancy argues the book's singular achievement is the powerful influence it has exerted upon its readers. In the spring of 1844, The Gentleman's Magazine attributed a sudden burst of charitable giving in Britain to Dickens's novella; in 1874, Robert Louis Stevenson waxed enthusiastic after reading Dickens's Christmas books and vowed to give generously; and Thomas Carlyle expressed a generous hospitality by staging two Christmas dinners after reading the book.[60] In America, a Mr. Fairbanks attended a reading on Christmas Eve in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1867, and was so moved he closed his factory on Christmas Day and sent every employee a turkey.[33] In the early years of the 20th century, the Queen of Norway sent gifts to London's crippled children signed "With Tiny Tim's Love"; Sir Squire Bancroft raised £20,000 for the poor by reading the tale aloud publicly; and Captain Corbett-Smith read the tale to the troops in the trenches of World War I.[61]

According to historian Ronald Hutton, the current state of observance of Christmas is largely the result of a mid-Victorian revival of the holiday spearheaded by A Christmas Carol. Hutton argues that Dickens sought to construct Christmas as a self-centred festival of generosity, in contrast to the community-based and church-centred observations, the observance of which had dwindled during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.[62] In superimposing his secular vision of the holiday, Dickens influenced many aspects of Christmas that are celebrated today in Western culture, such as family gatherings, seasonal food and drink, dancing, games, and a festive generosity of spirit.[63]

This simple morality tale with its pathos and theme of redemption significantly redefined the "spirit" and importance of Christmas, since, as Margaret Oliphant recalled, it "moved us all those days ago as if it had been a new gospel."[64] and resurrected a form of seasonal merriment that had been suppressed by the Puritan quelling of Yuletide pageantry in 17th-century England.[65]

Adaptations

The story has been adapted to other media including film, opera, ballet, a Broadway musical (1979's Comin' Uptown, which featured an all African-American cast), a BBC mime production starring Marcel Marceau, and Benjamin Britten's 1947 chamber orchestra composition Men of Goodwill: Variations on 'A Christmas Carol.[3]

References

- Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Kelly 12

- ^ a b c d Douglas-Fairhurst xxiv

- ^ a b c d e Douglas-Fairhurst viii

- ^ Pinkett, Lyn (2002). Charles Dickens. Palgrave MacMillan. p. 91. ISBN 0-333-72802-5.

- ^ Davis, Paul Benjamin (1990). The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge. Yale University Press. p. 178. ISBN 0-300-04664-2.

- ^ a b Kelly 10

- ^ a b Hearn xvi

- ^ Kelly 9

- ^ Kelly 11

- ^ Hearn xiv

- ^ Charles Dickens-The New York Times

- ^ Washington Irving, "Old Christmas"

- ^ Kelly 14

- ^ a b Douglas-Fairhurst xiii

- ^ Hearn xxxii

- ^ a b c Glancy x

- ^ a b c Ledger 119

- ^ a b c Kelly 15

- ^ Hearn xxxiii

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xvi

- ^ Hearn xxxiv

- ^ a b Restad 137

- ^ a b c d Kelly 19

- ^ Slater xvi

- ^ a b Ledger 117

- ^ a b Slater 43

- ^ a b c d e Douglas-Fairhurst xix

- ^ a b c Kelly 17

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xx,xvii

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xxxi

- ^ Varese, Jon Michael (22 December 2009). "Why A Christmas Carol was a flop for Dickens". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ Jaques, Edward Tyrrell (1914). Charles Dickens in chancery: being an account of his proceedings in respect of the "Christmas carol". Longmans, Green and Co. p. 5. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d Douglas-Fairhurst xx

- ^ Glancy 17

- ^ a b c Kelly 18

- ^ a b Glancy xii

- ^ Hearn lvii

- ^ Glancy xi

- ^ Restad 136

- ^ Restad 136–7

- ^ Restad 138

- ^ a b Restad 139

- ^ Restad 166,169

- ^ Slater 44

- ^ Standiford 168

- ^ Standiford 169

- ^ Nissenbaum 124

- ^ [1]

- ^ Kelly 28

- ^ Standiford 171–3

- ^ a b Douglas-Fairhurst xxi

- ^ a b c Douglas-Fairhurst xxii

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xxiii

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xxvi

- ^ Douglas-Fairhurst xxvii

- ^ a b c Douglas-Fairhurst xxviii

- ^ Slater 1971 xiv

- ^ Cochrane 126

- ^ Standiford 183

- ^ Glancy xii-xiii

- ^ Glancy xiii

- ^ Hutton 196

- ^ Kelly 9,12

- ^ Callow, 39

- ^ Kelly, 9–10

- Works cited

- Cochrane, Robertson (1996), Wordplay: origins, meanings, and usage of the English language, University of Toronto Press, p. 126, ISBN 0-8020-7752-8

- Callow, Simon (2009). Dickens' Christmas: A Victorian Celebration. frances lincoln ltd. ISBN 978-0-7112-3031-6. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Dickens, Charles (2006), A Christmas Carol and other Christmas Books, Oxford: Oxford University Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dickens, Charles (1998) [1988], Christmas Books, Oxford World Classics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-1928-3435-5

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dickens, Charles (2004), The Annotated Christmas Carol, W. W. Norton and Co., ISBN 0-393-05158-7

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dickens, Charles (2003), A Christmas Carol, Broadview Literary Texts, New York: Broadview Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dickens, Charles (1971), The Christmas Books, New York: Penguin

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Kelly, Richard Michael, ed. (2003). A Christmas Carol. Broadway Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-476-7. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- Ledger, Sally (2007), Dickens and the Popular Radical Imagination, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-84577-9

- Glancy, Ruth F. (1985), Dickens' Christmas Books, Christmas Stories, and Other Short Fiction, Michigan: Garland, ISBN 0-8240-8988-X

- Hutton, Ronald (1996), Stations of the Sun: The Ritual Year in England, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285448-8

- Nissenbaum, Stephen (1996), The Battle for Christmas, New York: Vintage Books (Random House), ISBN 0-679-74038-4

- Rowell, Geoffrey (1993–12), Dickens and the Construction of Christmas, History Today, 43:12

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - Restad, Penne L. (1995), Christmas in America: a History, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-510980-5

- Slater, Michael (2007), Charles Dickens, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-1992-1352-8

- Standiford, Les (2008), The Man Who Invented Christmas: How Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol Rescued His Career and Revived Our Holiday Spirits, New York: Crown, ISBN 978-0-307-40578-4

External links

- A Christmas Carol original manuscript facsimile at Morgan Library with transcription and audio

- A Christmas Carol at Internet Archive

- A Christmas Carol e-book with illustrations

- A Christmas Carol Project Gutenberg free online book

- A Christmas Carol Free solo audio version at Archive.org

- A Christmas Carol University of Glasgow Special Collections

- A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens Website

- Jonathan Winters' A Christmas Carol (from NPR)