Sense and Sensibility (film)

| Sense and Sensibility | |

|---|---|

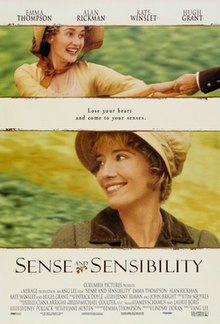

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ang Lee |

| Screenplay by | Emma Thompson |

| Produced by | Lindsay Doran |

| Starring | Emma Thompson Alan Rickman Kate Winslet Hugh Grant |

| Cinematography | Michael Coulter |

| Edited by | Tim Squyres |

| Music by | Patrick Doyle |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 136 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Languages | English French |

| Budget | $16 million |

| Box office | $134,993,774 |

Sense and Sensibility is a 1995 British-American period drama film directed by Ang Lee and based on Jane Austen's 1811 novel of the same name. English actress Emma Thompson wrote the script and stars as Elinor Dashwood, while Kate Winslet plays Elinor's younger sister Marianne. The story follows the Dashwood sisters; though they are members of a wealthy English family of landed gentry, circumstances result in their sudden destitution, forcing them to marry to secure their financial positions. Actors Hugh Grant and Alan Rickman play their respective suitors.

Producer Lindsay Doran, a longtime admirer of Austen's novel, hired Thompson to write the screenplay. The actress spent four years penning numerous revisions, continually working on the script between other films as well as into production of the film itself. Studios were nervous that Thompson – a first-time screenwriter – was the credited writer, but Columbia Pictures agreed to distribute the film. Though she initially intended another actress to portray Elinor, Thompson was persuaded to undertake the part herself, despite the wide disparity with her character's age.

The screenplay exaggerated the Dashwood family wealth to make their later scenes poverty more apparent to modern audiences. Doran and Thompson selected Ang Lee as director, both due to his work in the 1993 film The Wedding Banquet and because they felt he would help the film appeal to a wider audience. Given a budget of US $16 million, Lee approached filming from different perspectives than his cast and crew, resulting in culture shock before the actors grew to trust Lee's instincts.

A commercial success, the film garnered overwhelmingly positive reviews upon release and received many accolades, including three awards and eleven nominations at the 1995 British Academy Film Awards. It earned seven Academy Awards nominations, including for Best Picture and Best Actress (for Thompson). The actress received the Best Adapted Screenplay, becoming the only person to have won for both acting and writing awards at the Academy Awards. Sense and Sensibility contributed to a resurgence in popularity for Austen's works, and has led to many more productions in similar genres. It persists in being recognized as one of the best Austen adaptations of all time.

Plot

When Mr. Dashwood (Tom Wilkinson) dies, his wife (Gemma Jones) and three daughters – Elinor (Emma Thompson), Marianne (Kate Winslet) and Margaret (Emilie François) – are left with an inheritance consisting of only £500 a year, with the bulk of the estate of Norland Park left to his son John (James Fleet) from a previous marriage. John and his greedy, snobbish wife Fanny (Harriet Walter) immediately install themselves in the large house; Fanny invites her brother Edward Ferrars (Hugh Grant) to stay with them. She frets about the budding friendship between Edward and Elinor, believing he can do better, and does everything she can to prevent it from developing into a romantic attachment.

Sir John Middleton (Robert Hardy), a cousin of the widowed Mrs. Dashwood, offers her a small cottage house on his estate, Barton Park in Devonshire. She and her daughters move in, and are frequent guests at Barton Park. Marianne meets the older Colonel Brandon (Alan Rickman), who falls in love with her at first sight. Competing with him for her affections is the dashing but deceitful John Willoughby (Greg Wise), with whom Marianne falls in love. On the morning she expects him to propose marriage to her, he instead leaves hurriedly for London. Unbeknown to the Dashwood family, Brandon’s ward Beth, illegitimate daughter of his former love Eliza, is pregnant with Willoughby’s child, and Willoughby’s aunt Lady Allen has disinherited him upon discovering this.

Sir John’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Jennings (Elizabeth Spriggs), invites her daughter and son-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Palmer (Hugh Laurie and Imelda Staunton), to visit. They bring with them the impoverished Lucy Steele (Imogen Stubbs). Lucy confides in Elinor that she and Edward have been engaged secretly for five years, thus dashing Elinor’s hopes of a future with him. Mrs. Jennings takes Lucy, Elinor, and Marianne to London, where they meet Willoughby at a ball. He barely acknowledges their acquaintance, and they learn he is engaged to the extremely wealthy Miss Grey; Marianne is inconsolable. The clandestine engagement of Edward and Lucy also comes to light. Edward’s mother demands that he break off the engagement. When he honourably refuses, his fortune is taken from him and given to his younger brother Robert (Richard Lumsden).

On their way home to Devonshire, Elinor and Marianne stop for the night at the country estate of the Palmers, who live near Willoughby. Marianne cannot resist going to see Willoughby's estate and walks a long way in a torrential rain to do so. As a result, she becomes seriously ill and is nursed back to health by Elinor after being rescued by Colonel Brandon. Marianne recovers, and the sisters return home. They learn that Miss Steele has become Mrs. Ferrars and assume that she is married to Edward. However, he arrives to explain that Miss Steele has unexpectedly wed Robert Ferrars and Edward is thus released from his engagement. Edward proposes to Elinor and becomes a vicar, whilst Marianne falls in love with and marries Colonel Brandon.

Production

Conception and adaptation

In 1989, Lindsay Doran, the new president of production company Mirage Enterprises, was on a company retreat brainstorming potential film ideas when she suggested Sense and Sensibility to her colleagues.[2] The romance novel, published in 1811 as the début of English author Jane Austen, centred on the Dashwood sisters and their search for financial security after their family of landed gentry suddenly faces destitution. It had been adapted three times prior to the 1995 release, the last adaptation occurring in a 1981 serial.[3] Doran was a longtime fan of 'Sense and Sensibility',[4] and had vowed in her youth to someday adapt the novel if she ever entered the film industry.[5][6] She chose to adapt it in particular (rather than another work of Austen's) due to the presence of two female leads.[7] Doran stated, "All of [Austen's] books are funny and emotional, but Sense and Sensibility is the best movie story because it's full of twists and turns. Just when you think you know what's going on, everything is different. It's got real suspense, but it's not a thriller. Irresistible."[2] She also praised the novel for possessing "wonderful characters... three strong love stories, surprising plot twists, good jokes, relevant themes, and a heart-stopping ending."[6]

The producer spent ten years looking for a suitable screenwriter[5] – someone who was "equally strong in the areas of satire and romance" and could think in Austen’s language "almost as naturally as he or she could think in the language of the twentieth century."[6] Doran read screenplays by English and American writers[8] until she came across a series of comedic skits, often in period settings, that actress Emma Thompson had written.[9][10] Doran believed the humour and style of writing was "exactly what [she’d] been searching for."[11] A week after she and Doran wrapped production on Mirage’s 1991 film Dead Again, the producer selected Thompson to adapt Sense and Sensibility,[2] despite knowing that Thompson had never written a screenplay before.[11] A lover of Austen herself, Thompson first suggested they adapt Persuasion or Emma before agreeing to Doran's proposal.[12][13]

Thompson would spend four years writing and revising the screenplay, both during and in between shooting other films.[5][14][15] She approached the novel as a story of "love and money," noting that some people needed one more than the other.[16] Believing the novel's language to be "far more arcane than in [Austen's] later books," Thompson sought to simplify the dialogue while retaining the "elegance and wit of the original."[17] She observed that in a screenwriting process, first drafts often had "a lot of good stuff in it" but needed to be edited down, and second drafts would "almost certainly be rubbish... because you get into a panic."[18] Thompson credits Doran for "help[ing] me, nourish[ing] me and mentor[ing] me through that process... I learned about screenwriting at her feet."[19]

Thompson's first draft was at least 300 handwritten pages, which required her to edit it down to a more manageable length.[20][21] She found the romances to be the most difficult to "juggle,"[21] and her draft received some critical feedback for the way it presented Willoughby and Edward. Doran later recalled that people noted it didn't really "start until Willoughby arrives," with Edward side-lined as "backstory". Thompson and Doran quickly realized that "if we didn't meet Edward and do the work and take that twenty minutes to set up those people... then it wasn't going to work."[22] Gradually the screenplay focused as much on the Dashwood sisters' relationship with each other as it did with their romantic interests.[23]

During the writing process, executive producer Sydney Pollack stressed that the film be understandable to modern audiences, and that it be made clear why the Dashwood sisters could not just get a job.[5] "I'm from Indiana; if I get it, everyone gets it," he said.[24] Thompson believed that Austen was just as comprehensible in a different century, "You don't think people are still concerned with marriage, money, romance, finding a partner? Jane Austen is a genius who appeals to any generation."[9][25] She was keen on emphasising the realism of the Dashwoods' predicament in her screenplay,[26] and inserted scenes to make the differences in wealth more apparent to modern audiences. Thompson made the Dashwood family richer than in the book and added elements to help contrast their early wealth with their later financial predicament; for instance, because it might have been confusing to viewers that one could be poor and still have servants, Elinor is made to address a large group of servants at Norland Park early in the film for viewers to remember when they see their few staff at Barton Cottage.[27]

"In some ways I probably know that nineteenth century world better than English people today, because I grew up with one foot still in that feudal society. Of course, the dry sense of humour, the sense of decorum, the social code is different. But the essence of social repression against free will - I grew up with that."

— Ang Lee[28]

In possession of a screenplay draft, Doran next had to pitch the idea to various studios in order to finance the film, but found that many were wary of Thompson as the screenwriter, viewing her as too risky. Columbia Pictures executive Amy Pascal supported Thompson's involvement, and agreed to sign as the producer and distributor.[2][13] Despite not having heard of Austen prior to filming,[29] Taiwanese director Ang Lee was hired due to his work in the 1993 family comedy film The Wedding Banquet, which he co-wrote, produced, and directed. Doran felt that his films, which depicted complex family relationships amidst a social comedy context, were a good fit with Austen's storylines.[23] She recalled, "The idea of a foreign director was intellectually appealing even though it was very scary to have someone who didn't have English as his first language."[9] The producer sent Lee a copy of Thompson's script, to which he replied that he was "cautiously interested."[28] Fifteen directors were interviewed, but according to Doran, Lee was one of the few who "knew where the jokes were" and told them he wanted the film to "break people's hearts so badly that they'll still be recovering from it two months later."[28]

From the beginning, Doran desired that Sense and Sensibility should appeal to both a core audience of Austen aficionados as well as younger viewers attracted to romantic comedy films;[30] she felt that Lee's involvement prevented the film from becoming "just some little English movie" that appealed only to "audiences in Devon" instead of to "the whole world."[31] Lee said, "I thought they were crazy: I was brought up in Taiwan, what do I know about 19th-century England? About halfway through the script it started to make sense why they chose me. In my films I've been trying to mix social satire and family drama. I realized that all along I had been trying to do Jane Austen without knowing it. Jane Austen was my destiny. I just had to overcome the cultural barrier."[9] Because Thompson and Doran had worked on the screenplay for so long, Lee described himself at the time as a "director for hire," as he was unsure "where [his] position lay."[32] He spent six months in England "learn[ing] how to make this movie, how to do a period film, culturally... and how to adapt to the major league film industry."[32]

In January 1995, Thompson presented a draft to Lee, Doran, co-producer Laurie Borg, and others working on the production, and spent the next two months "revis[ing] the script constantly" based upon their feedback.[33] Thompson would continue making revisions throughout production of the film, including altering scenes due to budgetary concerns, adding dialogue improvements, and flexibly changing certain aspects to better fit the actors.[5] Brandon's confession scene, for instance, initially included flashbacks and stylised imagery before Thompson decided it was "emotionally more interesting to let Brandon tell the story himself and find it difficult."[34]

Casting

The casting process began in February 1995,[35] though some of the actors met with Thompson the previous year to help her conceptualize the script.[36] Thompson hoped that Doran would cast sisters Natasha and Joely Richardson as Elinor and Marianne Dashwood. Lee and Columbia Pictures wanted Thompson herself, now a "big-deal movie star," to play Elinor,[21] to which the actress replied that at age 35, she was too old for the 19-year-old character. Lee suggested Elinor's age be changed to 27, which would also have made the reality of spinsterhood easier for modern audiences to understand.[15][23] Thompson agreed, later stating that she was "desperate to get into a corset and act it and stop thinking about it as a script."[21]

Actress Kate Winslet initially intended to audition for the role of Marianne but the director disliked her work in the 1994 drama film Heavenly Creatures, causing her to audition for the lesser part of Lucy Steele. However, the actress pretended she had heard the audition was still for Marianne, and won the part based on a single reading.[23] Thompson later noted that despite being a nineteen-year-old "with the prospect of such a huge role" before her, Winslet approached the part "energised and open, realistic, intelligent, and tremendous fun."[37] The role helped Winslet become a recognisable movie star.[23]

Thompson wrote the part of Edward Ferrars with actor Hugh Grant in mind,[38] and he agreed to receive a lower salary in order to fit with the film's budget.[23] Grant called her screenplay "genius," explaining "I've always been a philistine about Jane Austen herself, and I think Emma's script is miles better than the book and much more amusing."[39] Grant's casting was met with criticism from the Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), who felt that he was too handsome for the part.[9] Thompson met her future husband Greg Wise, who played John Willoughby, whilst filming. He briefly dated Winslet during the production, and she later set him up with Thompson after Thompson's divorce with Kenneth Branagh was completed.[40]

Also appearing in the film was Alan Rickman, who portrayed Col. Christopher Brandon. Thompson was pleased that Rickman was able to demonstrate the "extraordinary sweetness [of] his nature," as he had played "Machiavellian types so effectively" in other films.[41] Twelve-year-old Emilie François, appearing as Margaret Dashwood, was one of the last people cast in the production, and had no professional acting experience.[42] Thompson praised the young actress in her production diaries, "Emilie has a natural quick intelligence that informs every movement – she creates spontaneity in all of us just by being there."[43]

Thompson had contacted many actors appearing in the film with an early draft of her screenplay, and was happy that Lee eventually cast all but one of them. They included Grant, Robert Hardy (as Sir John Middleton), Harriet Walter (as Fanny Ferrars Dashwood), Imelda Staunton (as Charlotte Jennings Palmer), and Hugh Laurie (as Mr. Palmer).[35] The fifth actor, Amanda Root, was excluded, having already committed herself to star in the 1995 film Persuasion.[21] Thompson noted of Laurie's casting, "There is no one [else] on the planet who could capture Mr. Palmer's disenchantment and redemption so perfectly, and make it funny."[44] Other cast members included Gemma Jones as Mrs. Dashwood, James Fleet as John Dashwood, Elizabeth Spriggs as Mrs. Jennings, Imogen Stubbs as Lucy Steele, Richard Lumsden as Robert Ferrars, Tom Wilkinson as Mr. Dashwood, and Lone Vidahl as Miss Grey.[45]

Costume design

According to Linda Troost, the costumes used in Sense and Sensibility helped emphasise the class and status of the various characters, particularly among the Dashwoods.[46] They were created by Jenny Beavan and John Bright, a team of designers best known for Merchant Ivory films who first began working together in 1984.[47][48] The two attempted to create accurate period dress,[46] and featured the "fuller, classical look and colours of the late 18th century."[49] They found inspiration in the works of English artists Thomas Rowlandson, John Hopper, and George Romney, and also reviewed fashion plates stored in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[50] The main costumes and hats were manufactured at Cosprop, a London-based costumer company.[50]

To achieve the tightly wound curls fashionably inspired by Greek art, some of the actresses wore wigs while others employed heated hair twists and slept in pin curls. Fanny, the snobbiest of the characters, possesses the tightest of curls but has less of a Greek silhouette, a reflection of her wealth and silliness.[50] Beaven stated that Fanny and Mrs. Jennings "couldn't quite give up the frills," and instead draped themselves in lace, fur, feathers, jewellery, and rich fabrics.[50] Conversely, sensible Elinor opts for simpler accessories, such as a long gold chain and a straw hat.[50] Fanny's shallow personality is also reflected in "flashy, colourful" dresses,[46] while Edward's buttoned-up appearance represents his "repressed" personality, with little visible skin.[51] Each of the 100 extras used in the London ballroom scene, depicting "soldiers and lawyers to fops and dowagers," don visually distinct costumes.[46][52]

For Brandon's costumes, Beavan and Bright consulted with Thompson and Lee and decided to have him project an image of "experienced and dependable masculinity."[51] Brandon is first seen in black, but later he wears sporting gear in the form of corduroy jackets and shirtsleeves. His rescue of Marianne has him transforming into the "romantic Byronic hero", sporting an unbuttoned shirt and loose cravat. In conjunction with his tragic backstory, Brandon's "flattering" costumes help appeal him to the audience.[53] For his wedding scene, Beavan and Bright consulted the National Army Museum about his "magnificent red and shiny gold braid-trimmed army uniform." Beavan commented, "Even though Colonel Brandon had left the army by now, he would have worn a new uniform for his wedding made by his military tailor."[50]

Filming

The film was budgeted at US $16 million,[54][55] the largest Ang Lee had yet received as well as the largest awarded to an Austen film that decade.[56] In the wake of the success of Columbia's 1994 film Little Women, the American studio authorised Lee's "relatively high budget" out of an expectation that it would be another cross-over hit and yield high box office returns.[30] Nevertheless, Doran called it a "low budget film"[57] and many of the ideas Thompson and Lee came up with – such as an early dramatic scene depicting Mr. Dashwood's bloody fall from a horse – were deemed unfilmable from a cost perspective.[58][59]

According to Thompson, Lee "arrived on set with the whole movie in his head".[60] Rather than focus on period details, he wanted his film to concentrate on telling a good story. He showed the cast select adaptations of novels, including Barry Lyndon and The Age of Innocence, which he believed to be "great movies; everybody worships the art work, [but] it's not what we want to do."[55] Lee criticised the latter film for lacking "energy," in contrast to the "passionate tale" of Sense and Sensibility.[55] The cast and crew experienced a "slight culture shock" with Lee on a number of occasions. He expected the assistant directors to be the "tough ones" and keep production on schedule, while they expected the same of him; this led to a slower schedule in the early stages of production.[61] Additionally, according to Thompson the director became "deeply hurt and confused" when she and Grant made suggestions for certain scenes, which was something that was not done in his native country.[9][23] Lee thought his authority was being undermined and lost sleep,[62] though this was gradually resolved as he became used to their methods.[63][64] The cast "grew to trust his instincts so completely," making fewer and fewer suggestions.[60] Co-producer James Schamus stated that Lee also adapted by becoming more verbal and willing to express his opinion.[65]

Lee became known for his "frightening" tendency to not "mince [his] words".[66] The director often had the actors do numerous takes for certain scenes in order to get the perfect shot,[9][28] and was not afraid to call something "boring" if he disliked it.[66] Thompson later recalled the director would "always come up to you and say something unexpectedly crushing", such as asking her not to "look so old."[62][67] She also commented, however, "he doesn't indulge us but is always kind when we fail."[68] Due to Thompson's extensive acting experience, the director encouraged her to practice t'ai chi to "help her relax [and] make her do things simpler."[55] Other actors soon joined them in meditating – according to Doran, it "was pretty interesting. There were all these pillows on the floor and these pale-looking actors were saying, 'What have we got ourselves into?' [Lee] was more focused on body language than any director I've ever seen or heard of."[55] He suggested Winslet read books of poetry and report back to him in order to best understand her character. He also had Thompson and Winslet live together to develop their characters' sisterly bond.[23] Many of the cast took lessons in etiquette and riding side-saddle.[69]

Lee found that in contrast to Chinese cinema,[62] he had to dissuade many of the actors from using a "very stagy, very English tradition. Instead of just being observed like a human being and getting sympathy, they feel they have to do things, they have to carry the movie."[55] Grant in particular often had to be restrained from giving an "over-the-top" performance; Lee later recalled that the actor is "a show stealer. You can't stop that. I let him do, I have to say, less 'star' stuff, the Hugh Grant thing ... and not (let) the movie serve him, which is probably what he's used to now."[55] For the scene in which Elinor learns Edward is unmarried, Thompson found inspiration from her reaction to her father's death.[70] Grant had been unaware that Thompson would cry through most of his speech, and the actress attempted to reassure him, "'There's no other way, and I promise you it'll work, and it will be funny as well as being touching.' And he said, 'Oh, all right,' and he was very good about it."[71] Lee had one demand for the scene, that Thompson avoid the temptation to turn her head towards the camera.[28]

Below: Montacute House, designated as a Grade I listed building by English Heritage, represented Cleveland House

Locations

Filming of Sense and Sensibility commenced in mid-April 1995 at a number of locations in Devon, beginning with Saltram House (standing in for Norland Park),[72][73] where Winslet and Jones shot the first scene of the production together reading about Barton Cottage.[74] As Saltram was a National Trust property, Schamus had to sign a contract before production began, and staff with the organization remained on set to carefully monitor the filming. Production later returned to shoot several more scenes, finishing there on 29 April.[75] The second location of filming, Flete House, stood in for part of Mrs. Jennings' London estate, where Edward first sees Elinor with Lucy.[76][77] Representing Barton Cottage was a Flete Estate stone cottage, which Thompson called "one of the most beautiful spots we've ever seen."[78]

Early May saw production at the "exquisite" village church in Berry Pomeroy for the final wedding scene.[79][80] From the tenth to the twelfth of May, Marianne's first rescue sequence was shot depicting her encounter with Willoughby. Logistics were difficult, as the scene was set upon a hill during a rainy day.[81] Lee shot around 50 takes, with the actors becoming soaked under rain machines; this led to Winslet eventually collapsing from hyperventilation.[62][82] Further problems occurred midway through filming, when Winslet contracted phlebitis in her leg, developed a limp, and sprained her wrist after falling down a staircase.[83] Thompson also experienced intense back pain on the final days of filming and was treated with acupuncture and Indocid.[84]

From May to July, production also took place at a number of other National Trust estates across England. Trafalgar House and Wilton House in Wiltshire stood in for the grounds of Barton Park and the London Ballroom respectively. Mompesson House, an eighteenth-century estate located in Salisbury, represented Mrs. Jennings' sumptuous townhouse. Sixteenth-century Montacute House in South Somerset was the setting for the Palmer estate of Cleveland House.[85] Sense and Sensibility was also shot at Compton Castle in Devon[86] and at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.[87]

Music

Composer Patrick Doyle, who had previously worked with his friend Emma Thompson in the films Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, and Dead Again, was hired to produce the music for Sense and Sensibility.[88] Tasked by the director to select existing music or compose new "gentle" melodies, Doyle wrote a "stifled" score that reflected the film's events.[89][90] He explained, "You had this middle-class English motif, and with the music you would have occasional outbursts of emotion."[88] Doyle noted that the score "becomes a little more grown-up" as the story progresses to one of "maturity and an emotional catharsis."[90] The score contains romantic elements[91][92] and has been described as a "restricted compass... of emotion" with "instruments [that] blend together in a gentle sort of way."[93] National Public Radio noted that as a reflection of the story, the score is a "little wistful... and sentimental."[93]

Two songs are sung by Marianne in the film, with lyrics adapted from seventeenth-century poems; Lee believed that the two songs conveyed the "vision of duality" visible both in the novel and script. The second song, Lee opined, expressed Marianne's "mature acceptance," intertwined with a "sense of melancholy". The melody of "Weep You No More Sad Fountains", Marianne's first song, appears in the opening credits, while her second song's melody features again during the ending credits, this time sung by dramatic soprano Jane Eaglen.[89] Doyle had to write Winslet's songs prior to filming began.[94] The composer received his first Academy Award nomination for his score.[92]

Editing

Thompson and Doran discussed how much of the love stories to depict, as the male characters spend much of the novel off-stage. The screenwriter had to carefully balance how much screentime she gave to the male leads, noting in her film production diary that such a decision would "very much lie in the editing."[95] Thompson wrote "hundreds of different versions" of romantic storylines. She considered having Edward re-appear midway through the film before deciding that it would not work as "there was nothing for him to do."[95] Thompson also opted to exclude the duel scene between Brandon and Willoughby, which is present in the novel, because it "only seemed to subtract from the mystery."[95] She and Doran agonized about when and how to input Brandon's backstory, as they wanted to prevent viewers from becoming bored. Thompson described the process of reminding audiences of Edward and Brandon as "keeping plates spinning".[96]

The film omits the characters of Lady Middleton and her children, as well as that of Ann Steele, Lucy's sister.[97] A scene was shot of Brandon finding his ward in a poverty stricken area in London, but this was edited out.[98] Thompson's script included a scene of Elinor and Edward kissing, as the studio "couldn't stand the idea of these two people who we've been watching all the way through not kissing."[99] However, it was one of the first scenes cut during the editing process: the original version was over three hours, Lee was less interested in the story's romance, and Thompson found a kissing scene to be inappropriate. The scene was still included in marketing materials and the film trailer.[99][100][101] Thompson and Doran also cut out a scene depicting a remorseful Willoughby when Marianne is sick. Doran said that despite it "being one of the great scenes in book history," they could not get it to fit into the film.[102]

Tim Squyres edited the film, his fourth collaboration with Ang Lee. He reflected in 2013 of his editing process, "It was the first film that I had done with Ang that was all in English, and it's Emma Thompson, Kate Winslet, Alan Rickman, and Hugh Grant — these great, great actors. When you get footage like that, you realize that your job is really not technical. It was my job to look at something that Emma Thompson had done and say, 'Eh, that's not good, I'll use this other one instead.' And not only was I allowed to pass judgment on these tremendous actors, I was required to."[103]

Themes and analysis

Thompson's screenplay has been noted for featuring significant alterations to the characters of Elinor and Marianne Dashwood. In the novel, the former embodies "sense" and the latter, "sensibility", but Lee's film turns these two characteristics around. Audience members are meant to view self-restrained Elinor as the person in need of reform, rather than her impassioned sister.[104] To better contrast them, Marianne and Willoughby's relationship includes an "erotic" invented scene in which the latter requests a lock of her hair – a direct contrast with Elinor's "reserved relationship" with Edward.[101] Lee also distinguishes them through imagery – Marianne is often seen with musical instruments, near open windows, and outside, while Elinor is pictured in door frames.[105] Another character altered for modern viewers is Margaret Dashwood, who conveys "the frustrations that a girl of our times might feel at the limitations facing her as a woman in the early nineteenth century."[106] Thompson uses Margaret for exposition in order to detail contemporary attitudes and customs. For instance, Elinor explains to a curious Margaret – and by extension, the audience – why their half-brother inherits the Dashwood estate.[106] Margaret's altered storyline, now containing interest in fencing and geography, also allows audience members to see the "feminine" side of Edward and Brandon, as they become father or brother figures to her.[101][107][108]

"The changes that Emma Thompson’s screenplay makes to the male characters, if anything, allow them to be less culpable, more likeable, and certainly less sexist or patriarchal."

— Devoney Looser[109]

When adapting the characters for film, Thompson found that in the novel, "Edward and Brandon are quite shadowy and absent for long periods," and that "making the male characters effective was one of the biggest problems. Willoughby is really the only male who springs out in three dimensions."[41] Several major male characters in Sense and Sensibility were consequently altered significantly from the novel in an effort to appeal to contemporary audiences.[110] Grant's Edward and Rickman's Brandon are "ideal" modern males who display an obvious love of children as well as "pleasing manners", especially when contrasted with Laurie's Palmer.[109] Thompson's script both expanded and omitted scenes from Edward's storyline, including the deletion of an early scene in which Elinor assumes that a lock of hair found in Edward's possession is hers, when in actuality it belongs to Lucy. These alterations have been viewed as an effort to make him more realised and honourable than in the novel and increase his appeal to viewers.[101][111] The character of Brandon also sustains alterations; Thompson's screenplay has his storyline directly mirroring Willoughby's – they are both similar in appearance, share a love of music and poetry and rescue Marianne in the rain while on horseback.[101][112][113]

Writing for The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen, Linda Troost discussed the "fusion adaptation" – a mixture of Hollywood style with the British heritage film genre, designed to appeal to a wide range of viewers. Tracing its origin to the BBC's unsuccessful 1986 Austen adaptation Northanger Abbey, Troost noted that Lee's production "exaggerat[ed] social differences for the benefit of viewers not familiar with the book" and prominently featured "radical feminist and economic issues" while "paradoxically endors[ing] the conservative concept of marriage as a woman's goal in life."[114] However, Troost believed that regardless of its American producers, Sense and Sensibility is faithful to the heritage genre through its use of locations, costumes, and attention to details.[46] Andrew Higson noted that while Sense and Sensibility includes commentary on sex and gender, it fails to pursue issues of class. Thompson's script, he wrote, displays a "sense of impoverishment [but] is confined to the still privileged lifestyle of the disinherited Dashwoods. The broader class system is pretty much taken for granted."[115]

Lee's films have often explored the theme of having one's freedom be limited by societal rules.[116][117] He cited Sense and Sensibility while directing his 2000 film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, noting that "family dramas [like Sense and Sensibilty] are all about conflict, about family obligations versus free will."[118]

Marketing and release

In the United States, Sony and Columbia Pictures released Sense and Sensibility on a "relatively slow" schedule when compared to mainstream films, first premiering it on 13 December 1995.[30] Believing that a limited release would position the film both as an "exclusive quality picture" and increase its chances of winning Academy Awards, Columbia dictated that its first weekend involve only seventy cinemas in the US; it opened in eleventh place and earned $721,341.[65][119][120] The film's release was slowly expanded until it was present in over one thousand cinemas across the US.[119] To gain the greatest benefit of the publicity surrounding Academy Award nominees, the film's release was timed to coincide with "Oscar season".[30] Sense and Sensibility's release saw several brief increases both when the nominees were announced and during the time of the ceremony in late March.[119] By the end of its release in the US, it garnered an "impressive" total domestic gross of $43,182,776.[119][121]

Due to Austen's reputation as a serious author, the producers were able to rely on high-brow publications to help market their film. Near the time of its US release, large spreads in The New York Review of Books, Vanity Fair, Film Comment, and other media outlets featured columns on Lee's production.[122] In late December, Time magazine declared it and Persuasion to be the best films of 1995.[123] Andrew Higson referred to all this media exposure as a "marketing coup" because it meant the film "was reaching one of its target audiences."[122] Meanwhile, most promotional images featured the film as a "sort of chick flick in period garb."[122] New Market Press published Thompson's screenplay and film diary;[124][125] in its first printing, the hard cover edition sold 28,500 copies in the US.[126] British publisher Bloomsbury released a paperback edition of the novel containing film pictures, same title design, and the cast's names on the cover, whilst Signet Publishing in the US printed 250,000 copies instead of the typical 10,000 a year; actress Julie Christie read the novel in an audiobook released by Penguin Audiobooks.[127][128] Sense and Sensibility increased dramatically in terms of its book sales, ultimately hitting tenth place on the The New York Times Best Seller list for paperbacks in February 1996.[129]

In the United Kingdom, Sense and Sensibility was released on 23 February 1996 in order to "take advantage of the hype from Pride and Prejudice", another popular Austen adaptation recently released. Columbia Tristar's head of UK marketing noted that "if there was any territory this film was going to work, it was in the UK."[119] After receiving positive responses from previewing audiences members, marketing strategies focused on selling it as both a costume drama and as a film attractive to mainstream audiences.[130] Attention was also paid to marketing Sense and Sensibility internationally. Because the entire production cycle had consistently emphasised it as being "bigger" than a normal British period drama literary film, distributors avoided labelling it as "just another English period film."[131] Instead, marketing materials featured quotations from populist media outlets such as the Daily Mail, which compared the film to Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994).[131] Worldwide, the film ultimately grossed $134,582,776,[120] a sum that was considered a box office success.[65][132] It had the largest box office gross out of the Austen adaptations of the 1990s.[56]

Reception

"This Sense And Sensibility is stamped indelibly by Ang Lee's characteristically restrained direction... Although somewhat older than one might expect Elinor to be, Emma Thompson invests the character with a touching vulnerability, while Kate Winslet, who made such an eye catching debut in Heavenly Creatures last year, perfectly catches the confusions within the idealistically romantic but betrayed Marianne."

— Michael Dwyer in a positive review for The Irish Times[133]

The film received a review score of 98 percent according to review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, which summarised that "Sense and Sensibility is an uncommonly deft, very funny Jane Austen adaptation, marked by Emma Thompson's finely tuned performance."[134] It landed on more than one hundred top-ten lists.[23] In her work Jane Austen on Film and Television: A Critical Study of the Adaptations, Sue Parrill praised the 1995 film, writing that with "a sterling screenplay, a high-powered cast, a talented director, and a delightful soundtrack, this film is a winner in all respects."[135] Film critic John Simon gave praise to most of the film, particularly focusing on Thompson's performance, though he criticised Grant for being "much too adorably bumbling... he urgently needs to chasten his onscreen persona, and stop hunching his shoulders like a dromedary."[136]

In a positive review, Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle lauded the film for containing a sense of urgency "that keeps the pedestrian problems of an unremarkable 18th century family immediate and personal."[137] LaSalle concluded that the adaptation has a "right balance of irony and warmth. The result is a film of great understanding and emotional clarity, filmed with an elegance that never calls attention to itself."[137] Writing for Variety magazine, Todd McCarthy observed that the film's success was assisted by its "highly skilled cast of actors", as well as its choice of Lee as director. McCarthy clarified, "Although [Lee's] previously revealed talents for dramatizing conflicting social and generational traditions will no doubt be noted, Lee's achievement here with such foreign material is simply well beyond what anyone could have expected and may well be posited as the cinematic equivalent of Kazuo Ishiguro writing The Remains of the Day."[138]

Jarr Carr of The Boston Globe thought that Lee "nail[ed] Austen's acute social observation and tangy satire," and viewed Thompson and Winslet's age discrepancy as a positive element that helps feed the dichotomy of sense and sensibility.[139] Contributing to The Mail on Sunday, William Leith found Sense and Sensibility to be "an extremely sharp, subtle, clever, lovely looking film" that was superior to the serial Pride and Prejudice. Leith especially saved praise for the cast, writing that Grant plays his role "masterfully" and Walter "conveys sour bitchiness like you never thought she could."[140] In 2011, The Guardian film critic Paul Laity named it his favourite film of all time, partly because of its "exceptional screenplay, crisply and skilfully done."[141]

Awards and nominations

Out of the Austen adaptations of the 1990s, Sense and Sensibility received the most recognition from Hollywood.[142] It garnered seven Academy Award nominations at the 68th Academy Awards ceremony, where Thompson received the Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay,[143] making her the only person to have won an Oscar for both her writing and acting (Thompson won the Best Actress award for Howards End, in 1993).[144][145] The film also was the recipient of twelve BAFTA nominations at the 49th British Academy Film Awards; Sense and Sensibility won for Best Film, Best Actress in a Leading Role (for Thompson), and Best Actress in a Supporting Role (for Winslet).[146] In addition, Sense and Sensibility earned awards and nominations at the 53rd Golden Globe Awards, the 1st Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards, and the 2nd Screen Actors Guild Awards.[147][148][149] The film won the Golden Bear at the 46th Berlin International Film Festival.[150]

Legacy and influence

Sense and Sensibility was the first English-language period adaptation of an Austen novel to appear in cinemas in over fifty years.[151][152] The year 1995 saw a resurgence of popularity for Austen's works, as Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice both rocketed to critical and financial success.[153][154] The two adaptations helped draw more attention to the previously little known 1995 television film Persuasion, and led to more Austen adaptations in the following years.[155] Between 1995 and 1996, six Austen adaptations were ultimately released onto film or television.[152] The filming of these productions led to a surge in popularity at many of the landmarks and locations depicted;[89] according to scholar Sue Parrill, they became "instant meccas for viewers."[14]

When Sense and Sensibility was released in cinemas in the US, Town & Country published a six-page article entitled "Jane Austen's England", which focused on the landscape and sites shown in the film. A press book released by the studio as well as Thompson's published screenplay and diaries listed all the filming locations, helping to boost tourism. Saltram House for instance was carefully promoted during the film's release, and saw a 57 percent increase in attendance.[156][157] In 1996, JASNA's membership increased by fifty percent.[158] The popularity of both Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice led to the BBC and ITV releasing their Austen adaptations from the 1970s and 1980s onto DVD.[159]

As the mid-1990s included four Austen adaptations, little room was left to adapt the author's other remaining novels. In his book Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking since the 1990s, Andrew Higson argued that as a result, the adaptations left a "variety of successors" in the genres of romantic comedy and costume drama, as well as with films featuring strong female characters. Cited examples included Mrs Dalloway (1997), Mrs. Brown (1997), Shakespeare in Love (1998), and Bridget Jones's Diary (2001).[160] In 2008, Andrew Davies, the screenwriter of Pride and Prejudice, adapted Sense and Sensibility for television. Viewing Lee's film as too sentimental, Davies' production featured events found in the novel but excluded from Thompson's screenplay, such as Willoughby's seduction of Eliza and his duel with Brandon. Davies also cast actors closer to the ages in the source material.[161]

Sense and Sensibility has maintained its popularity into the twenty-first century. In 2004, Louise Flavin referred to the 1995 film as "the most popular of the Austen film adaptations,"[162] and in 2008, The Independent ranked it as the third best Austen adaptation of all time, opining that Lee "offered an acute outsider's insight into Austen in this compelling 1995 interpretation of the book [and] Emma Thompson delivered a charming turn as the older, wiser, Dashwood sister, Elinor."[163] Journalist Zoe Williams credits Thompson as the person most responsible for Austen's popularity, explaining in 2007 that Sense and Sensibility "is the definitive Austen film and that's largely down to her."[164] Wendy S. Jones, author of Consensual Fictions: Women, Liberalism, And The English Novel, praised Thompson for her fidelity to the source material, referring to the film as "one of the most authentic" of the adaptations of the 1990s.[165]

See also

- 1995 in film

- Jane Austen in popular culture

- List of awards and nominations received by Emma Thompson

- Styles and themes of Jane Austen

References

- ^ "'Sense and Sensibility' (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 15 December 1995. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Mills, Nancy (17 March 1996). "Book Sense; Lindsay Doran Kept Her Sites On Bringing 'Sense And Sensibility' To The Screen". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Parrill 2002, pp. 21, 24.

- ^ Dole 2002, p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e Stempel 2000, p. 249.

- ^ a b c Doran 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Dobie 2003, p. 249.

- ^ Doran 1995, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Jane Austen Does Lunch". The Daily Beast. 17 December 1995. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (5 January 1996). "Thompson Sees a Lot Of Sense In Jane Austen's Sensibilities". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ a b Doran 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Doran 1995, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Silverstein, Melissa (24 August 2010). "Interview With Lindsay Doran: Producer Nanny McPhee Returns". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ^ a b Parrill 2002, p. 6.

- ^ a b Roberts, Laura (16 December 2010). "British actresses who made their name starring in Jane Austen adaptations". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 255. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 252. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:33:00–01:33:25.

- ^ Rickey, Carrie (23 August 2010). "Emma Thompson on child rearing, screenwriting and acting". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Welsh, Jim (1 January 1996). "A Sensible Screenplay". Literature/Film Quarterly. Retrieved 27 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ a b c d e f Thompson, Anne (15 December 1995). "Emma Thompson: Write for the Part". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:33:25–01:33:49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Miller, Frank. "Sense and Sensibility". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 265. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Kroll, Jack (13 December 1995). "Hollywood Reeling Over Jane Austen's Novels". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved 27 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Stuart, Jon (10 December 1995). "Emma Thompson, Sensibly: The levelheaded actress turns screenwriter with her adaptation of Jane Austen's 'Sense and Sensibility.' (And please, let's have no mention of you-know-who.)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 5:40–6:25.

- ^ a b c d e Kerr, Sarah (1 April 1996). "Sense and Sensitivity". New York. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ Mills 2009, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Higson 2011, p. 155.

- ^ Higson 2004, p. 46.

- ^ a b Stock, Francine (21 January 2013). "In conversation with Ang Lee". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 207–10. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 251. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ a b Thompson 1995, p. 210. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 9:45–9:53.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 216. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 9:15–9:30.

- ^ Gilbert, Matthew (7 May 1995). "Hugh Grant The Englishman who went up the Hollywood mountain and came down a star". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 26 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Thomas, Liz (27 March 2010). "The luvvie triangle: How Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet had on-set romances with the same man". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ^ a b Thompson 1995, p. 269. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 5:13–5:20.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 246–47. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 251–52. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ "Sense and Sensibility (1995)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Troost 2007, p. 83.

- ^ Nadoolman Landis 2012.

- ^ Gritten, David (25 March 2006). "Why we should love and leave the world of Merchant Ivory". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 July 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ Roberts, Kathaleen (12 October 2008). "Clothes Make the Movies: 'Fashion in Film' showcases outstanding period costumes". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved 23 July 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f Goodwin, Betty (15 December 1995). "Fashion / Screen Style". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 July 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Gay 2003, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 258. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Gay 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Mills 2009, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f g Warren, Michael (22 September 1995). "Ang Lee on a Roll: The director of The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink". AsianWeek. Retrieved 27 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ a b Higson 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 20:00–20:20.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 207–08. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 1:11–2:25.

- ^ a b Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:02:00–01:03:45.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 221. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ a b c d Mills 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 220, 240. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 17:00–17:20.

- ^ a b c Mills 2009, p. 72.

- ^ a b Dawes, Amy (13 December 1995). "Remaking the classics director, cast find yin, yang in Austen tale". Los Angeles Daily News. Retrieved 26 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 4:20–4:40.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 212–13. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 266–67. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Lyall, Sarah (5 November 2006). "Beauty Is Much Less Than Skin Deep". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ "The Sense and Sensibility estate, Saltram House, Devon". The Guardian. 7 June 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 215, 217–19. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 215, 217, 222, 226–27. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Voigts-Virchow 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 224. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 233. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Britten, Nick (18 July 2010). "Weddings fall at Sense and Sensibility church after bells break". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 230. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 235–37. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 6:15–6:25.

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 261–62. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, p. 276. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson 1995, pp. 286–87. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ "Other special places to visit". National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Rose, Steve (10 July 2010). "This week's new film events". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ a b Webber, Brad (1 March 1996). "Composer's Classical Music Makes `Sense' In Movies". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ a b c Parrill 2002, p. 43.

- ^ a b Horn, John (13 March 1996). "Score one for the movies: composers translate plot, character and setting into Oscar-nominated music". Rocky Mountain News. Retrieved 14 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Carter, Darryl. "Sense and Sensibility – Patrick Doyle". Allmusic. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ a b Chapman, Glen (21 April 2011). "Music in the movies: Patrick Doyle". Den of Geek. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ a b Hansen, Liane (10 March 1996). "Film Scores – The Men Who Make the Music – Part 2". National Public Radio. Retrieved 14 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Cripps, Charlotte (15 October 2007). "Classical Composer aims to score for charity". The Independent. Retrieved 14 April 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ a b c Thompson 1995, p. 272. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFThompson1995 (help)

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 9:30–9:50.

- ^ Flavin 2004, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:29:10–01:29:50.

- ^ a b Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:30:00–01:30:35.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 141.

- ^ a b c d e Stovel 2011.

- ^ Thompson & Doran 1995, 01:59:00–01:59:15.

- ^ Bierly, Mandi (22 February 2013). "Oscar-nominated editors clear up the biggest category misconception". Entertainment Weekly. CNN. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ^ Flavin 2004, pp. 42–43, 46.

- ^ Kohler-Ryan & Palmer 2013, p. 56.

- ^ a b Parrill 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Flavin 2004, p. 44.

- ^ Nixon 2002, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Looser 1996.

- ^ Parrill 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Flavin 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Nixon 2002, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Troost 2007, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 150.

- ^ McRae 2013, p. 35.

- ^ Kohler-Ryan & Palmer 2013, p. 41.

- ^ McRae 2013, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Higson 2011, p. 157.

- ^ a b "Sense and Sensibility (1995)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results for January 26-28, 1996". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Higson 2011, p. 156.

- ^ "The Best Of 1995: Cinema". Time. 25 December 1995. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Lauerman, Connie (15 December 1995). "Happy Ending". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ Greenfield 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Higson 2011, pp. 129–30.

- ^ Higson 2004, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 129.

- ^ Thompson 2003, p. 13.

- ^ Higson 2011, pp. 157–58.

- ^ a b Higson 2011, p. 158.

- ^ Higson 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Dwyer, Michael (8 March 1996). "Tea, tears and sympathy "Sense And Sensibility" (PG) Savoy, Virgin, Omniplex, UCIs, Dublin". The Irish Times. Retrieved 23 July 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ "Sense and Sensibility (1995)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Parrill 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Simon 2005, p. 484.

- ^ a b LaSalle, Mick (13 December 1995). "A Fine `Sensibility', Emma Thompson adapts Jane Austen's classic story". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (3 December 1995). "Sense and Sensibility". Variety. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ^ Carr, Jay (13 December 1995). "Thompson makes glorious 'Sense'". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 23 July 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Leith, William (25 February 1996). "Needle work". The Mail on Sunday. Retrieved 23 July 2013 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Laity, Paul (25 December 2011). "My favourite film: Sense and Sensibility". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2012.

- ^ Parrill 2002, p. 4.

- ^ "Nominees & Winners for the 68th Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. (26 March 1996). "'Braveheart' Is Top Film; Cage, Sarandon Win". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Andrew (28 March 2010). "Emma Thompson: How Jane Austen saved me from going under". The Independent. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ "Awards Database". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "HFPA - Awards Search". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ Associated Press (8 January 1996). "'Sense and Sensibility' is best-film pick". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ "The 2nd Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- ^ "Berlinale: 1996 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Higson 2011, p. 125.

- ^ a b Parrill 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Higson 2004, p. 38.

- ^ Dale, Arden; Pilon, Mary (6 December 2010). "In Jane Austen 2.0, the Heroines And Heroes Friend Each Other". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Greenfield 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Higson 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Higson 2011, pp. 149–50.

- ^ Greenfield 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Troost 2007, p. 75.

- ^ Higson 2011, pp. 158–59.

- ^ Conland, Tara (19 January 2007). "Davies turns up heat on Austen". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Flavin 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Hoggard, Liz (24 July 2008). "Senseless sensibility". The Independent. Retrieved 7 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Winterman, Denise (9 March 2007). "Jane Austen - why the fuss?". BBC News. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 101.

- Bibliography

- Dole, Carole M (2002). "Austen, Class, and the American Market". In Greenfield, Sayre N (ed.). Jane Austen in Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 58–78. ISBN 978-0-8131-9006-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doran, Lindsay (1995). Sense and Sensibility: The Screenplay and Diaries. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-55704-782-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flavin, Louise (2004). Jane Austen in the Classroom: Viewing the Novel/reading the Film. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 0-8204-6811-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gay, Penny (2003). "Sense and Sensibility in a Post-Feminist world: Sisterhood is Still Powerful". In MacDonald, Gina; MacDonald, Andrew (eds.). Jane Austen on Screen. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–110. ISBN 0-52179-325-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Greenfield, Sayre N. (2001). Jane Austen in Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9006-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Higson, Andrew (2004). "English Heritage, English Literature, English Cinema: Selling Jane Austen to Movie Audiences in the 1990s". In Voigts-Virchow, Eckart (ed.). Janespotting and Beyond: British Heritage Retrovisions Since the Mid-1990s. Gunter Narr Verlag Tubingen. pp. 35–50. ISBN 3-8233-6096-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Higson, Andrew (2011). Film England: Culturally English Filmmaking Since the 1990s. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-84885-454-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jones, Wendy S. (2005). Consensual Fictions: Women, Liberalism, And The English Novel. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-80208-717-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kohler-Ryan, Renee; Palmer, Sydney (2013). "What Do You Know of My Heart?: The Role of Sense and Sensibility in Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility and Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon". In Arp, Robert; Barkman, Adam; McRae, James (eds.). The Philosophy of Ang Lee. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 41–63. ISBN 978-0-8131-4166-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Looser, Devoney (1996). "Jane Austen 'Responds' to the Men's Movement". Persuasions On-Line. 18: 150–170. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McRae, James (2013). "Conquering the Self: Daoism, Confucianism, and the Price of Freedom in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon". In Arp, Robert; Barkman, Adam; McRae, James (eds.). The Philosophy of Ang Lee. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 19–40. ISBN 978-0-8131-4166-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mills, Clifford W. (2009). Ang Lee. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 1-60413-566-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nadoolman Landis, Deborah (2012). Filmcraft: Costume Design: Costume Design. Focal Press. ISBN 978-02408-1867-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nixon, Cheryl L (2002). "Balancing the Courtship Hero: Masculine Emotional Display in Film Adaptations of Austen's Novels". In Greenfield, Sayre N (ed.). Jane Austen in Hollywood. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 22–43. ISBN 978-0-8131-9006-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Parrill, Sue (2002). Jane Austen on Film and Television: A Critical Study of the Adaptations. McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. ISBN 0-7864-1349-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobie, Madeleine (2003). "Gender and the Heritage Film: Popular Feminism Turns to History". Jane Austen and Co: Remaking the Past in Contemporary Culture. State University of New York Press. pp. 247–260. ISBN 0-7914-5616-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Simon, John Ivan (2005). John Simon On Film: Criticism, 1982-2001. Applause Books. ISBN 978-1557835079.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stempel, Tom (2000). Framework: A History of Screenwriting in the American Film. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0654-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stovel, Nora (2011). "From Page to Screen: Emma Thompson's Film Adaptation of Sense and Sensibility". Persuasions On-Line. 32 (1). Retrieved 30 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Emma (1995). Sense and Sensibility: The Screenplay and Diaries. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-55704-782-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doran, Lindsay (1995b). Audio commentary for Sense and Sensibility (DVD). Special Features: Columbia Pictures.

{{cite AV media}}:|first1=missing|last1=(help) - Thompson, James (2003). "How to Do Things with Austen". Jane Austen and Co: Remaking the Past in Contemporary Culture. State University of New York Press. pp. 13–33. ISBN 0-7914-5616-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - Troost, Linda V (2007). "The Nineteenth-century Novel on Film: Jane Austen". In Cartmell, Deborah; Whelehan, Imelda (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Literature on Screen. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–89. ISBN 978-0521614863.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Voigts-Virchow, Eckart (2004). Janespotting and Beyond: British Heritage Retrovisions Since the Mid-1990s. Gunter Narr Verlag Tubingen. ISBN 3-8233-6096-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Use dmy dates from August 2011

- 1995 films

- 1990s romantic drama films

- British films

- British romantic drama films

- American films

- American romantic drama films

- English-language films

- French-language films

- Films directed by Ang Lee

- Screenplays by Emma Thompson

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Films based on works by Jane Austen

- Films set in England

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Georgian-era films

- Golden Bear winners

- Romantic period films

- Columbia Pictures films