Steinway & Sons

| |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Musical instruments |

| Founded | March 5, 1853[1] |

| Founder | Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg[2] (later Henry E. Steinway) |

| Headquarters | New York City, United States[3] 40°46′45″N 73°53′59″W / 40.7793°N 73.8998°W Hamburg, Germany[3] 53°34′27″N 9°55′27″E / 53.5743°N 9.9241°E |

Number of locations | 200 authorized dealers operating 300 showrooms worldwide[4] |

Area served | Worldwide[4] |

Key people | Michael T. Sweeney CEO, worldwide (since 2013) Manfred Sitz Managing director, Europe (since 2012) Ron Losby President, Americas (since 2008) |

| Products | Grand pianos[5][6] Upright pianos[7][8] |

Production output | 2,500 new pianos (annually)[9] |

| Services | Restoration of Steinway pianos[10] |

| Parent | Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc.[11] |

| Website | www eu |

Steinway & Sons, also known as Steinway /ˈstaɪnweɪ/ , is an American and German piano company, founded in 1853 in Manhattan, New York City by German immigrant Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg (later known as Henry E. Steinway).[12] The company's growth led to the opening of a factory in Queens, New York City and a factory in Hamburg, Germany.[13] The factory in New York City supplies the Americas and the factory in Hamburg supplies the rest of the world.[14][15]

Steinway is a prominent piano company,[16][17] known for making pianos of high quality[18][19] and for its influential inventions within the area of piano development.[20][21] The company's share of the high-end grand piano market consistently exceeds 80 percent.[22] Its status as the world's elite piano manufacturer has been secured in part because of the success of marketing strategies such as the Steinway Artist program,[23] which was invented in the 1870s by William Steinway,[24] a son of the company founder.[25] Steinway uses a multi-pronged strategy and the keystone of the Steinway strategy was and remains quality.[16] The company holds a royal warrant by appointment to Queen Elizabeth II.[26]

Steinway pianos have been recognized with numerous awards.[27] One of the first was a gold medal won in 1855 – two years after the company's foundation – at the American Institute Fair at the New York Crystal Palace.[28][29] From 1855 to 1862 Steinway pianos received 35 gold medals.[27][30] Several awards and recognitions followed,[31] including 3 medals at the International Exposition of 1867 in Paris.[32] Steinway has been granted 126 patents in piano making; the first patent was achieved in 1857.[33]

Steinway pianos are handcrafted at the factories in New York City and Hamburg.[3] In addition to the flagship Steinway piano line, Steinway markets two less expensive brands of piano sold under the secondary brand names Boston and Essex. The Boston brand is for the mid-level market and the Essex brand is for the entry-level market. Boston and Essex pianos are designed in the United States. To take advantage of lower costs of part production and labor, they are made in Asia at non-Steinway factories under the supervision of Steinway employees.[34][35]

History

Foundation and growth

Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg first made pianos in the 1820s from his house in Seesen, Germany.[36] He made pianos under the Steinweg brand until he emigrated from Germany to America in 1850 with his wife and eight of his nine children.[37] The eldest son, C.F. Theodor Steinweg, remained in Germany, and continued making the Steinweg brand of pianos, partnering with Friedrich Grotrian, a piano dealer, from 1856 to 1865.[38]

In 1853, Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg founded Steinway & Sons. His first workshop in America was in a small loft at the back of 85 Varick Street in the Manhattan district of New York City.[39] The first piano made by Steinway & Sons was given the number 483 because Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg had built 482 pianos in Germany. Number 483 was sold to a New York family for $500, and is now on display at the German museum Städtisches Museum Seesen in Seesen,[40] the town in which Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg lived before he sat off for America.[41] A year later, demand was such that the company moved to larger premises at 82–88 Walker Street. It was not until 1864 that the family anglicized their name from Steinweg to Steinway.[42]

By the 1860s, Steinway had built a new factory at Park Avenue and 53rd Street, the present site of the Seagram Building, where it covered a whole block. With a workforce of 350 men, production increased from 500 to 1,800 pianos per year. The pianos themselves underwent numerous substantial improvements through innovations made both at the Steinway factory and elsewhere in the industry based on emerging engineering and scientific research, including developments in the understanding of acoustics.[43] Almost half of the company's 126 patented inventions were developed by the first and second generations of the Steinway family. Steinway's pianos won several important prizes at exhibitions in New York City, Paris and London.[44][45] By 1862, Steinway pianos had received more than 35 medals.[27][31]

In 1865, the Steinway family sent a letter to C.F. Theodor Steinweg asking that he leave the German Steinweg factory (by now located in Braunschweig, known in English as Brunswick) and travel to New York City to take over the leadership of the family firm due to the deaths of his brothers Henry and Charles from disease.[38] C.F. Theodor Steinweg obeyed, selling his share of the German piano company to his partner, Wilhelm Grotrian (son of Friedrich Grotrian), and two other workmen, Adolph Helfferich and H.G.W. Schulz. The German factory changed its name from C.F. Theodor Steinweg to Grotrian, Helfferich, Schulz, Th. Steinweg Nachf. (English: Grotrian, Helfferich, Schulz, successors to Th. Steinweg), later shortened to Grotrian-Steinweg.[38] In New York City, C.F. Theodor Steinweg anglicized his name to C.F. Theodore Steinway. During the next 15 years of his leadership he kept a home in Braunschweig and traveled often between Germany and the United States.[38]

Around 1870–80, William Steinway (born Wilhelm Steinweg, a son of Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg) established a professional community, the company town Steinway Village, in what is now the Astoria section of Queens in New York City.[13] Steinway Village was built as its own town, and included a new factory (still used today) with its own foundry and sawmill, houses for employees, kindergarten, lending library, post office, volunteer fire department and parks. Steinway Village later became part of Long Island City. Steinway Street, one of the major streets in the Astoria and Long Island City neighborhoods of Queens, is named after the company.[12]

Part of Steinway's growing reputation arose from its successes in trade fairs.[23] The company won a gold medal at the 1867 Paris Exposition, prevailing over Chickering and Sons. At Philadelphia's Centennial Exposition of 1876, the competition was principally between Steinway, Chickering and Weber. According to journalist James Barron's account of Steinway's participation in the competition, the company was able to secure success by bribing one of the judges. William Steinway denied to the exposition's organizers that a judge had been paid directly, although Barron states that the judge was bribed through an intermediary: the pianist Frederic Boscovitz.[46] William Steinway would admit in his personal diaries that under his leadership the US arm of the company bribed judges at trade fairs to favor Steinway pianos.[47]

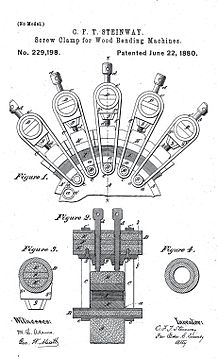

To reach European customers who wanted Steinway pianos, and to avoid high European import taxes, William Steinway and C.F. Theodore Steinway established a new piano factory in the free German city of Hamburg in 1880.[48] The first address of Steinway's factory in Hamburg was at Schanzenstraße in the western part of Hamburg, St. Pauli. C.F. Theodore Steinway became the head of the German factory, and William Steinway went back to the factory in New York City. The Hamburg and New York City factories regularly exchanged experience about their patents and technique despite the large distance between them, and they continue to do so today. C.F. Theodore Steinway was a talented inventor who made many improvements in the construction of the piano.[49] More than a third of Steinway's patented inventions are under the name of C.F. Theodore Steinway.[50] He died in Braunschweig in 1889, having successfully competed against the Grotrian-Steinweg brand – both the Hamburg-based Steinway factory and the Braunschweig-based Grotrian-Steinweg factory became known for making premium German pianos.[48]

Meanwhile, the 1880s saw the company embroiled in a series of labor disputes between the company and its US workers. One dispute, in 1880, saw the company lead an industry-wide lockout of piano workers. In later disputes in the decade, the company hired detectives to spy on its workers, paid police for their backing, and evicted strike leaders from company housing.[51]

In 1890, Steinway received their first royal warrant, granted by Queen Victoria.[52][53] The following year the patrons of Steinway included the Prince of Wales and other members of the monarchy and nobility.[52] In subsequent years Steinway was granted royal and imperial warrants from the rulers of Italy, Norway, Persia, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Sweden and Turkey.[54]

Steinway Halls

Steinway Hall (German: Steinway-Haus) is the name given to some buildings housing concert halls, showrooms and sales departments for Steinway pianos. In 1864 William Steinway, the son of Henry E. Steinway who is credited with establishing Steinway's success in marketing, built a set of elegant new showrooms housing more than 100 pianos on East 14th Street in Manhattan, New York City. In 1866, William Steinway oversaw the construction of the first Steinway Hall to the rear of the showrooms. The Steinway Hall seated 2,500 people and quickly became one of New York City's most prominent cultural centers,[55] housing the New York Philharmonic for the next 25 years until Carnegie Hall opened in 1891.[56] Concertgoers had to pass through the piano showrooms; this had a remarkable effect on sales, increasing demand for new pianos by four hundred in 1867 alone.[57] The Steinway Hall on East 14th Street was closed in 1925 and a new Steinway Hall on West 57th Street was opened the same year. In 2013 Steinway sold the Steinway Hall on West 57th Street for $46 million and moved out of the building in the end of 2014.[58] A new Steinway Hall is planed to open on Avenue of the Americas in 2015.[59][60]

In 1904, a Steinway-Haus was established in Hamburg as a sales showroom with concert halls, practice studios, sales departments, and piano storage space. In 1909, another Steinway-Haus opened in Berlin. A Steinway-Haus is similar to a Steinway Hall. Today Steinway Halls and Steinway-Häuser are located in world cities such as New York City,[61] London,[62] Berlin,[63] and Vienna.[64]

Expansion

In 1857 Steinway began to make a line of art case pianos, designed by artists.[66][67] In 1903 the 100,000th Steinway grand piano was given as a gift to the White House; it was decorated by the artists Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Maria Oakey Dewing under the supervision of the head of Steinway's Art Piano Department, Joseph Burr Tiffany. The 100,000th Steinway grand piano was replaced in 1938 by the 300,000th, which remains in use in the White House.[68][69] The piano is normally placed in the largest room of the White House, the East Room.[70]

Later Steinway diversified into the manufacture of player pianos. Several systems such as the Welte-Mignon, Duo-Art, and Ampico were incorporated.[71] During the 1920s Steinway had been selling up to 6,000 pianos a year. In 1929, Steinway constructed one double-keyboard grand piano. It had 164 keys and four pedals. (In 2005, Steinway refurbished this instrument).[72] After 1929, piano production went down, and during the Great Depression, Steinway made only a little more than 1,000 pianos per year. In the years between 1935 and World War II, demand rose again.

During World War II the Steinway factory in New York City received orders from the Allied Armies to build wooden gliders to convey troops behind enemy lines. Steinway could make few normal pianos, but built 2,436 special models called the Victory Vertical or G.I. Piano. It was a small piano that four men could lift, painted olive drab, gray, or blue, designed to be carried aboard ships or dropped by parachute from an airplane to bring music to the soldiers.[73]

The factory in Hamburg, being American-owned, could sell very few pianos during World War II. No more than a hundred pianos per year left the factory. In the later years of the war, the company was ordered to give up all the prepared and dried wood their lumber yard held for war production. In an air raid over Hamburg, several Allied bombs hit the factory and nearly destroyed it. After the war, Steinway restored the Hamburg factory with help from the Marshall Plan.[74] Eventually, the post-war cultural revival boosted demand for entertainment and Steinway increased piano production at the New York City and Hamburg factories, going from 2,000 in 1947 to 4,000 pianos a year by the 1960s.

In the late 1960s, Steinway brought countersuit against Grotrian-Steinweg to stop them from using the name Steinweg on their pianos.[75] Steinway won the case on appeal in 1975, forcing their competitor to use only the name Grotrian in the United States.[76] The case set a precedent and established the concept of Initial Interest Confusion, in which consumers might be initially attracted to a similarly named but lesser-known brand because of the stronger brand's good reputation.[77]

In 1972, after a lengthy strike, increased competition from Yamaha,[78] a long-running financial struggle, high legal expenses, and a lack of business interest among some of the Steinway family members, the firm was sold to CBS.[79] At that time CBS owned many enterprises in the entertainment industry, including guitar maker Fender, electro-mechanical piano maker Rhodes, and the baseball team New York Yankees. CBS had plans to form a musical conglomerate that made and sold music in all forms and through all outlets, including records, radio, television, and musical instruments.[80] This new conglomerate was evidently not as successful as CBS had expected, and Steinway was sold in 1985, along with classical and church organ maker Rodgers and flute and piccolo maker Gemeinhardt, to a group of Boston-area investors.[80][81] In order to acquire Steinway, the investors founded the musical conglomerate Steinway Musical Properties.[82] In 1995, Steinway Musical Properties merged with the Selmer Company to form the musical conglomerate Steinway Musical Instruments,[83] which was named Company of the Year in 1996 by The Music Trades: "As the industry's most recognized trademark Steinway & Sons is synonymous with piano quality worldwide ... Steinway's success has been hard-won on the factory floors in Long Island City and Hamburg, Germany, and on retail showrooms around the world." The award was given in recognition of Steinway's "overall performance, quality, value-added products, a well-executed promotional program and disciplined distribution which generated the most impressive results in the entire music industry."[84] Steinway Musical Instruments acquired the flute manufacturer Emerson in 1997, the piano keyboard maker Kluge in 1998, and the Steinway Hall in New York City in 1999. The conglomerate made more acquisitions in the following years.[85] From 1996 to 2013, Steinway Musical Instruments was traded at the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) under the abbreviation LVB, for Ludwig van Beethoven.[86][87]

Recent history

In 1988, Steinway made its 500,000th piano. The piano was designed by artist Wendell Castle.[88] The names of the 832 pianists and 90 ensembles on the Steinway Artist roster of 1987 are written on the piano,[89] including Vladimir Horowitz, Van Cliburn, and Billy Joel.[90]

In 1994, Steinway opened the C.F. Theodore Steinway School for Concert Technicians, also known as the Steinway Academy; the world's first academy for concert technicians worldwide.[91] Georges Ammann, concert technician with Steinway's factory in Hamburg, said, "We were getting a lot of complaints from pianists all over the world – they said that getting their pianos tuned was a disastrous process every time and that the local technicians were hopeless. The artists kept begging us to do something about this ... From that perspective, it was clear that an institution like the Steinway Academy was a necessity."[92] The Steinway Academy provides professional concert technicians with a two-week intensive course.[92]

By the year 2000, Steinway had made its 550,000th piano.[93][94] The company updated and expanded production of its two other brands, Boston and Essex pianos, in addition to the flagship Steinway & Sons. More Steinway Halls and Steinway Piano Galleries opened across the world, mainly in China, Japan and Korea.

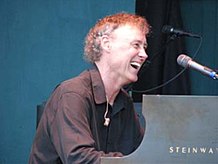

In 2003, Steinway celebrated its 150th anniversary at Carnegie Hall's largest auditorium, the Isaac Stern Auditorium and Ronald O. Perelman Stage, with a gala series of three concerts on June 5, 6 and 7, 2003.[95][96] The concert on June 5 featured classical music with Kit Armstrong (a music child prodigy), Van Cliburn, Eroica Trio, Gary Graffman, Ben Heppner, Yundi Li and Güher and Süher Pekinel. The host was Charles Osgood. On June 6 was a concert of jazz featuring Peter Cincotti, Herbie Hancock, Ahmad Jamal, Al Jarreau, Ramsey Lewis, Tisziji Muñoz, Chucho Valdés and Nancy Wilson, hosted by Billy Taylor. Pop music was the focus of June 7, with Paul Shaffer hosting performances by Art Garfunkel, Bruce Hornsby, k.d. lang, Michel Legrand, Brian McKnight, Peter Nero and Roger Williams. As part of the 150th anniversary, fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld created a commemorative Steinway art case piano.[94][97]

In April 2005, Steinway celebrated the 125th anniversary of the establishment of Steinway's factory in Hamburg. Steinway employees, together with artists, dealers and friends from around the world celebrated the anniversary at the Laeiszhalle concert hall in Hamburg with a gala concert, culminating in a showcase performance by Lang Lang, Vladimir and Vovka Ashkenazy, and Detlef Kraus. As part of the celebration, the 125th anniversary limited edition Steinway art case piano by designer Count Albrecht von Goertz was presented to the public.[98]

Until his death on September 18, 2008 at the age of 93, Henry Z. Steinway, the great-grandson of the Steinway founder, still worked for Steinway and put his signature on custom-made limited edition pianos. At several public occasions, Henry Z. Steinway represented the Steinway family.[99] He started at the company in 1937 after graduating from Harvard University. He was president of the company from 1955 to 1977 and was the last Steinway family member to be president of Steinway.[100]

On January 24, 2009, Steinway installed what at the time was the world's largest solar-powered rooftop air-conditioning and dehumidification system, at a cost of $875,000, to dehumidify the factory in New York City, and protect the pianos.[103][104] Lower humidity in the factory provides a more stable environment for the construction of the pianos.

After the 2008 economic downturn, Steinway grand piano sales fell by half and 30 percent of the union employees were laid off from the New York factory between August 2008 and November 2009.[105] Sales were down 21 percent in 2009 in the United States.[105] As of 2010, sales began increasing a little and in 2011 sales increased further.[106][107]

On John Lennon's 70th birthday anniversary in the fall of 2010, Steinway introduced a new series of 104 limited edition grand pianos designed on the basis of the white Steinway grand piano that John Lennon owned.[108][109] The piano can be seen in the 1971 film footage that features John Lennon performing Imagine[110] for his wife Yoko Ono at his home in England and in Sean Lennon's much debated photo from 2010 showing pop musician Lady Gaga playing the piano.[111] The 104 limited edition pianos are designed in conjunction with Yoko Ono,[112] who owns the original piano, which today is placed at her residence, The Dakota, in New York City.[109] The 104 pianos are identical to John Lennon's white piano with the exception that the limited pianos feature drawings, lyrics and notes by John Lennon and incorporate laser engravings of his signature.[109] Yoko Ono gave Steinway access to four of her John Lennon drawings and 26 of each are used in the design of the pianos.[113]

In June 2013, private equity firm Kohlberg & Company offered to buy Steinway parent company Steinway Musical Instruments for $438 million.[114] On August 14, 2013, hedge fund Paulson & Co. made a higher offer of $512 million to take the company private; the Steinway Musical Instruments board recommended that shareholders accept it. In September 2013, Paulson & Co. announced the completion of the acquisition.[115][116]

Piano models

Steinway pianos are sold by a worldwide network of around 200 authorized Steinway dealers who operate around 300 showrooms.[4]

Grands and uprights

Steinway makes the following models of grand pianos and upright pianos:

Steinway's factory in New York City makes six models of grand piano and three models of upright piano.[5][7]

- Grand pianos: S (5'1"), M (5'7"), O (5'10 3/4"), A (6'2"), B (6'11"), D (8'11 3/4")

- Upright pianos: 4510, 1098, K-52

Steinway's factory in Hamburg makes seven models of grand piano and two models of upright piano.[6][8] (The numerical portion of the grand piano model designations represent the length of the case in centimetres).

Special designs

Designers and artists such as Karl Lagerfeld,[94][97] Louis Comfort Tiffany[117][118] and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema[119] have created original designs for Steinway pianos. These specially designed pianos fall under the series Steinway Art Case Pianos or Steinway Limited Edition Pianos.

Steinway began creating art case pianos in 1857 and the making of art case pianos reached its peak in the late 19th century. Today, Steinway only builds art case pianos on rare occasions. The art case pianos are unique, because Steinway builds only one of each. Some of Steinway's most notable art case pianos are the Alma-Tadema grand piano from 1887, the 100,000th Steinway piano from 1903, the 300,000th Steinway piano from 1938 and the Sound of Harmony from 2008. The Alma-Tadema grand piano was designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and received great public acclaim when it was exhibited in London.[120] The piano has a complicated hand-carved case, lid and legs and is decorated with paintings and 2,200 mother-of-pearl inlays.[121] It was bought by Henry Gurdon Marquand for his New York City mansion. In 1997, it was sold at Christie's auction house in London for $1.2 million, setting a price record for a piano sold at auction.[121][122] It is now on display at the art museum Clark Art Institute.[120] The 100,000th Steinway piano was given as a gift to the White House in 1903 and is made of cherry tree with gold leaf. It is decorated with coats of arms of the thirteen original states of America and painted by Thomas Dewing with dancing figures representing the nine Muses. The 100,000th Steinway piano was replaced in 1938 by the 300,000th Steinway piano. The gold gilded mahogany legs of the 300,000th piano are carved as eagles and are moulded by sculptor Albert Stewart.[65] The piano remains in use in the White House.[68][69] The Sound of Harmony is decorated with inlays of 40 different woods, including the lid, which replicates artwork by Chinese painter Shi Qi.[123] It took about four years[124] to build the grand piano and it was priced at €1.2 million.[123] The piano was chosen for use at the Expo 2010 Shanghai China.[124]

The series of limited edition pianos encompasses pianos of new designs and replicas of historic Steinway pianos. Examples of pianos of new designs include The S.L.ED by Karl Lagerfeld created to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the Steinway company in 2003,[94][97] and the 125th anniversary grand piano by Count Albrecht von Goertz designed to celebrate the 125th anniversary in 2005 of the foundation of the Steinway factory in Hamburg.[98] An example of replicas of historic Steinway pianos is the 150th anniversary grand piano, which are exact copies of the grand piano played by Ignacy Jan Paderewski on his famous United States concert tour from 1892 to 1893.[125] Another example of replicas of historic Steinway pianos is the William E. Steinway grand piano, which are exact copies of the award-winning Steinway grand piano, that was exhibited at the Centennial Exposition in 1876.[126]

In 1999, Steinway introduced a new line of specially designed pianos, the Steinway Crown Jewel Collection.[127] The collection consists of grand and upright pianos in Steinway's traditional design, but instead of the traditional ebony finish the pianos of the Steinway Crown Jewel Collection are made in veneers of rare woods from around the world.[128] The collection contains wood veneers such as Macassar ebony, East Indian rosewood, and kewazinga bubinga.[129]

Piano brands

Other than the expensive Steinway & Sons brand, Steinway markets two budget brands: Boston for the mid-level market and Essex for the entry-level market. Boston and Essex pianos are made using lower-cost components and labor. Pianos of these two brands, made with Steinway owned designs, are manufactured in Asia by suppliers.[34][35] Steinway allows only its authorized Steinway dealers to carry new Boston and Essex pianos.[130]

- Boston: made for the general mid-ranged piano market at lower prices than Steinway's name brand. Boston pianos are manufactured at the Kawai piano factory in Hamamatsu, Japan. There are five sizes of Boston grands and three sizes of Boston uprights available in a variety of finishes. Grand piano models are GP-156 PE, GP-163 PE, GP-178 PE, GP-193 PE and GP-215 PE. Upright piano models are UP-118E PE, (UP-118S PE), UP-126E PE and UP-132E PE. Boston pianos incorporate some of the features of Steinway pianos such as a wider tail design (a feature of the Steinway piano models A-188, B-211, C-227 and D-274) resulting in a larger soundboard area than conventionally shaped pianos of comparable sizes, a maple inner rim, and Steinway's patented Octagrip pin-block.[34]

- Essex: made for the entry-range market and is cheaper than Steinway and Boston pianos. Since 2005, Essex pianos are made at the Pearl River piano factory in Guangzhou, China. Prior to 2005, they were made by Young Chang in Korea. There are two sizes of Essex grands and three to four sizes of Essex uprights available in a wide variety of finishes and furniture designs. Like the Boston pianos, Essex pianos incorporate some of the features of Steinway pianos as well: a wider tail design, an all-wood action with Steinway geometry with rosette-shaped hammer flanges, and reinforced hammers with metal fasteners.[35]

Piano bank

Steinway maintains a "piano bank" from which performing pianists, especially Steinway Artists, can select a Steinway piano for use in a certain concert, recording, or tour.[131] The idea is to provide a consistent pool of Steinway pianos with various characteristics for performing pianists' individual touch and tonal preferences. Performing artists choose a piano for use at a certain venue after trying some of the pianos of the "piano bank". This allows a range of Steinway pianos with various touch and tonal characteristics to be available for performers to choose from.[131] Steinway takes responsibility for preparing, tuning, and delivering the piano of the performer's choice to the designated concert hall or recording studio. The performer bears the cost of these services.[13][132] The pianos for the "piano bank" are selected by Steinway personnel.

The "piano bank" is worldwide and consists of more than 400 Steinway pianos valued collectively at over $25 million.[131][133]

Manufacture

New York City and Hamburg factories

Some pianists of the past and some active pianists today have expressed a preference for Steinway pianos made at Steinway's factory in New York City or at Steinway's factory in Hamburg.[134] Larry Fine, American piano technician and author of the known The Piano Book, considers Hamburg Steinways to be of a higher quality than New York Steinways.[135] Emanuel Ax, concert pianist and piano teacher at the Juilliard School,[136] says that "... the differences have more to do with individual instruments than with where they were made."[134] However that may be, some visual differences are well known, for example: the Hamburg models have a high polish polyester finish and rounded corners; New York models have a satin lustre lacquer finish and square or Sheraton corners.[134] As of 2011, the New York Steinway factory is making high polish polyester finish pianos in addition to satin lustre lacquer finish.[137]

At present, the New York Steinway factory builds approximately 1,250 Steinway pianos a year. The Hamburg factory builds about the same number. The market is loosely divided into two sales areas: the New York Steinway factory, which supplies North and South America, and the Hamburg Steinway factory, which supplies the rest of the world. At all main Steinway showrooms across the world, customers can order pianos from either factory. The New York and Hamburg factories exchange parts and craftsmanship so they "make no compromise in quality," in the words of Steinway's founder Henry E. Steinway.[138] Steinway parts for both factories come from the same places: Canadian maple is used for the rim, and the soundboards are made from Sitka spruce from Alaska. Both factories use similar crown parameters for their diaphragmatic soundboards. To maintain quality, Steinway has acquired some of its suppliers. Steinway bought the German manufacturer Kluge in Wuppertal, which supplies keyboards, in December 1998, and in November 1999, purchased the company that supplies its cast iron plates, O.S. Kelly Co. in Springfield, Ohio.[85]

The majority of the world's concert halls have at least one Steinway concert grand piano model D-274, some (for example Carnegie Hall) have model D-274s from both the New York City factory and the Hamburg factory so they can satisfy a greater range of preferences.[139]

Components

Each Steinway grand piano consists of more than 12,000 individual parts.[10] A Steinway piano is handmade[140] and takes a year to build.[141]

Steinway maintains own lumber yards at both the New York factory and the Hamburg factory, aging and drying lumber from nine months to five years. Less than 50 percent is finally used in the making of Steinway pianos. More than 70 percent of the walnut stock is discarded. The woods are purchased when they are available rather than when they are needed.[142]

Case

Steinway piano cases are made of up to 18 layers of hard rock maple,[143][144] which are glued and pressed together into one piece in one operation, and then pressed into shape using a rim-bending process that Steinway patented in 1878.[145] The layers may be up to 25 ft (7.62 m) long.[146] Beams in the bottom of the grand pianos or in the backs of the vertical pianos provide additional support. For braces and posts, Steinway pianos use spruce. After the rim-bending process, the rim has to rest from the stress of being bent. It is placed in a conditioning room for a minimum of 6 weeks, depending on thickness and size of the rim. The room's temperature is set at 85°F (30°C) and the relative humidity is 45 percent.[147]

Plate

Inside the piano, a cast iron plate provides the strength to support the string tension from 16 tons up to 23 tons.[150] The iron plate is installed in the case above the soundboard and is bronzed,[148] lacquered, polished, and decorated with the Steinway logo. Steinway fabricates plates in its own foundry using a sand-casting method.

Soundboard

Steinway makes its soundboard from solid spruce, which allows the soundboard to transmit and amplify sound.[151] Individual pieces of spruce are matched to make soundboards of uniform color and tonal quality. The soundboards found in Steinway pianos are double-crowned with Steinway's diaphragmatic design. The diaphragmatic soundboard was granted a patent in 1936.[152]

Bridges

Soundboard bridges are glued to the top side of the soundboard to transmit vibrations from the strings to the soundboard. Steinway bridges are made of vertically laminated hard rock maple with a solid maple cap.[153] They are bent to a specifically defined contour to optimize sound transmission. The bridge is measured for specific height requirements for each piano and is hand-notched.[153] The bridges are then glued down and doweled into the ribs for structural integrity.

Strings and pin-block

The pianos have steel strings in the midsection and treble, and bass strings are made of copper-wound steel. The strings are uniformly spaced with one end coiled around the tuning pins, which in turn are inserted in a laminated wooden block called the pin-block or wrestplank. The tuning pins keep the strings tight and are held in place by friction. The strings found on a Steinway piano are made of tensile Swedish steel.[148] Steinway also employs front and rear duplex scales. C.F. Theodore Steinway's relationship with Hermann von Helmholtz led to the development and Steinway patent in 1872 of front and back aliquots, allowing the traditionally dead sections of strings to vibrate with other strings.[148]

The wrestplank is a multi-laminated block of wood into which the tuning pins are inserted. The wrestplank in Steinway pianos is made of hard rock maple. The Steinway Hexagrip Wrestplank pin-block, patented in 1963, is made from seven thick, quarter-sawn maple planks whose grain is oriented radially for evenly distributed end-grain exposure to the tuning pins.[148]

Keys and action

Steinway's 88 keys are made of Bavarian spruce.[148] Each of the keys transmits its movement to a small, felt-covered wooden hammer that strikes one, two, or three strings when the note is played. The quarter-sawn maple action parts are mounted on a metallic frame, which consists of seamless brass tubes with rosette-shaped contours, force-fitted with maple dowels and brass hangers. The surface of the white keys is made of polymer, but was earlier made of elephant ivory. During the 1950s Steinway switched from using elephant ivory, which would later be outlawed in 1975 due to the international treaty CITES.[154]

In 1963, Steinway introduced its "Permafree" action for New York-built grand pianos, using Teflon parts in place of cloth bushings. The Teflon was intended to withstand wear and humidity changes better than cloth. The Teflon bushings resulted in certain unforeseen problems mainly during changes in weather, they were discontinued in 1982. Hamburg-made Steinway pianos never implemented the Teflon bushings.

Affiliates

Steinway Artists

In contrast to other piano makers, who presented their pianos to pianists, William Steinway engaged the Russian pianist Anton Rubinstein to play Steinway pianos during Rubinstein's first and only American concert tour from 1872 to 1873, with 215 concerts in 239 days.[155] It was a success for both Rubinstein and Steinway.[156] Thus, the Steinway Artist program was born.[24][157] Later the Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski toured America playing 107 concerts on Steinway pianos in just 117 days.[158]

Today, more than 1,600 concert artists and ensembles are official Steinway Artists,[159] which means that they have chosen to perform on Steinway pianos exclusively, and each owns a Steinway.[160] None are paid to do so.[161][162] Steinway Artists come from every genre: classical, jazz, rock, and pop. A few examples of Steinway Artists are Daniel Barenboim,[163] Harry Connick, Jr.,[164] Billy Joel,[165] Evgeny Kissin,[166] Diana Krall,[167] and Lang Lang;[168][169] and a few examples of "immortals" are Benjamin Britten,[170] Duke Ellington,[171] George Gershwin,[171] Vladimir Horowitz,[172] Cole Porter,[171] and Sergei Rachmaninoff.[169][173] Also piano ensembles are on the Steinway Artist roster, for example Eroica Trio,[174] Güher and Süher Pekinel,[174] Katia and Marielle Labèque,[175] and The 5 Browns.[176] These ensembles consist of pianists, who are all Steinway Artists. In 2009, Steinway developed a new program for young artists, Young Steinway Artists. The program is open to talented pianists between the ages of 16 and 35.[177][178]

Steinway expects Steinway Artists to perform on Steinway pianos where they are available and in appropriate condition.[179] Artur Schnabel complained once that "Steinway refused to let me use their pianos [i.e., Steinway pianos owned by Steinway] unless I would give up playing the Bechstein piano – which I had used for so many years – in Europe. They insisted that I play on Steinway exclusively, everywhere in the world, otherwise they would not give me their pianos in the United States. That is the reason why from 1923 until 1930 I did not return to America. ... [in] 1933, Steinway changed their attitude and agreed to let me use their pianos in the United States, even if I continued elsewhere to play the Bechstein piano... Thus, from 1933 on, I went every year to America."[180] In 1972, Steinway responded to Garrick Ohlsson's statement that Bösendorfer was "the Rolls-Royce of pianos" by trucking away the Steinway-owned Steinway concert grand piano that Ohlsson was about to give a recital on at Alice Tully Hall in New York City. Ohlsson ended up performing on a Bösendorfer piano borrowed at the eleventh hour, and Steinway would not let him borrow Steinway-owned instruments for some time. Ohlsson has since made peace with Steinway.[179] Angela Hewitt was removed from the Steinway Artist roster around 2002 after she purchased and performed on a Fazioli piano.[179] After the Canadian pianist Louis Lortie was removed from the Steinway Artist roster in 2003,[181] he complained in a newspaper article that Steinway is trying to establish a monopoly on the concert world by becoming "the Microsoft of pianos."[179] A Steinway spokesman said, in response to Lortie's decision to perform a concert on a Fazioli piano, that "I don't want anyone on our roster ... who doesn't want to play the Steinway exclusively."[179]

According to musicologist Stuart de Ocampo, "That Steinway aggressively sought out and paid[when?] (in various forms) for artist endorsements must be stressed in order to combat an idealistic notion that the greatest flocked to Steinway simply because it was the best." More generally, Stuart de Ocampo endorses the view of Donald W. Fostle, who wrote in a company history of Steinway that "the genius of Steinways ... ultimately lay in their ability to persuade millions of persons across decades and continents that in this realm of supreme subjectivity, individual variation, incertitude, and ever-changing conditions, there was an absolute best. The assertion, repeated often enough, took on the coloration of fact", but Stuart de Ocampo concludes that "Innovations in piano construction carved out a unique sound for the Steinway pianos in the mid-nineteenth century. Medals at fairs and international exhibitions were the basis of Steinway & Sons' early reputation."[23] Paying for pianists' endorsements back then was not specific to Steinway. As there were financial incentives for testimonials, several famous pianists had no qualms about endorsing more than one piano brand. Franz Liszt endorsed Steinway, Bösendorfer, Chickering and Sons, Erard, Ibach, Mason & Risch, and Steck at the same time.[182] Today, no pianist is paid by Steinway,[16][22] and when Steinway Artists loan pianos from Steinway for a concert or recording session the artists do have to pay Steinway for preparing, tuning, and delivering of the piano.[183] According to management academic David Liebeskind, the Steinway Artist program "... is one of the only pure product endorsements programs, as no artist is paid to play on or endorse a Steinway piano."[16]

The Steinway Artist program has been copied by other piano companies,[184][185] but Steinway's program is unique in that a pianist must promise to play pianos of the Steinway brand only to become a Steinway Artist.[162][179] The Steinway Artist designation restricts a pianist's use of pianos by other makers and implies an obligation to perform on Steinway pianos.[186]

All-Steinway Schools

An All-Steinway School is an educational institution in which students perform and are taught exclusively on Steinway-designed pianos.[187][188] Steinway does not offer their pianos free of charge, but requires that the institutions buy them.[16] The Oberlin Conservatory of Music in Ohio holds the longest partnership with Steinway.[189] They have used Steinway pianos exclusively since 1877, 24 years after Steinway was founded. In 2007, they obtained their 200th Steinway piano. Other examples of All-Steinway Schools are the Yale School of Music at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the Cleveland Institute of Music in Ohio, Royal Holloway, University of London in England, the University of Melbourne Faculty of VCA and MCM in Victoria, Australia, the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, China, and the University of South Africa in Pretoria.[187][188]

In 2007, the Crane School of Music, at the State University of New York at Potsdam, was added to the All-Steinway School roster, receiving 141 pianos in one $3.8 million order.[190] In 2009, the University of Cincinnati – College-Conservatory of Music in Ohio became designated an All-Steinway School, based on a $4.1 million order of 165 new pianos, one of the largest orders Steinway has ever processed.[191][192]

There are more than 170 All-Steinway Schools around the world.[187]

Piano competitions and music festivals

Several international piano competitions use Steinway pianos.[193] Steinway has been selected exclusively by such competitions as the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in Fort Worth, Texas, the Gina Bachauer International Piano Competition in Salt Lake City, Utah, the Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in Brussels, Belgium, the Ferruccio Busoni International Piano Competition in Bolzano, Italy, and the Long-Thibaud-Crespin Competition in Paris.[193] Also well-known music festivals around the world use Steinway pianos. The festivals feature a range of musical forms and styles. A few examples are the Montreal International Jazz Festival, Canada, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, Louisiana, The Proms in Royal Albert Hall, London, the Verbier Festival in the mountain resort of Verbier, Switzerland, and the Saito Kinen Festival Matsumoto in the Japanese Alps near Matsumoto.[194]

The International Steinway Festival was first held in 1987 in Hamburg, Germany.[195][196] Since 1990, the festival has been held every two years. Each contestant has won first prize in a national Steinway piano competition.[195]

Steinway Societies

A Steinway Society is a local, nonprofit organization.[197][198][199] An example is the Steinway Society of Central Florida with the mission "To stimulate and nourish the musical knowledge and artistic talents of disadvantaged youth. To provide an opportunity for young piano students, proficient in their skills, to work toward a higher level of excellence. To encourage performance experience, audition preparation, and scholarship assistance for further study in classical and jazz piano. To provide musically talented students with a loaner piano and/or tuition for piano lessons through the establishment of a Piano Bank."[200]

Steinway Societies are located in places such as Central Florida,[201] Garda in Italy,[202] Massachusetts,[203] Michigan,[204] Nashville in Tennessee,[205] New Orleans,[206] Riverside County and the Coachella Valley in California,[207] and Western Pennsylvania.[208]

Price records

Steinway pianos have been among the most expensive in the world:

- The world's most expensive grand piano is a Steinway art case piano built by Steinway's factory in Hamburg in 2008 for €1.2 million.[123] It took Steinway about four years to build the piano.[124] The piano is named Sound of Harmony and is decorated with inlays of 40 different woods, including the lid, which replicates artwork by Chinese painter Shi Qi.[123] The piano is owned by the art collector Guo Qingxiang and was chosen for use at the Expo 2010 Shanghai China.[124]

- The world's most expensive grand piano sold at auction was built by Steinway's factory in New York City from 1883 to 1887; it sold for $1.2 million in 1997 at Christie's in London.[121][122] By setting this record, Steinway broke its own 1980 price record of $360,000.[209] The grand piano is on display at the art museum Clark Art Institute.[120]

- The world's most expensive upright piano was built by Steinway's factory in Hamburg in 1970. The piano was bought by John Lennon for $1,500;[210] Lennon composed and recorded Imagine and other tunes on it. In 2000, it was sold at auction by a British private collector. Pop musician George Michael made the winning bid of £1.67 million.[211]

Awards

This lithograph by Amédée de Noé a.k.a. Cham conveys the wild popularity of the Steinway piano, the musicality of which had just been demonstrated by famed pianist Désiré Magnus at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris.[32] (Harper's Weekly, August 10, 1867, reporting on the world exposition).

The Steinway company and its leaders have won numerous awards, including:[44][45]

- In 1839, Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg exhibited three pianos at the state trade exhibition in Braunschweig, Germany and was awarded a gold medal.[212]

- In 1855, Steinway attended the Metropolitan Mechanics Institute fair in Washington, D.C. and won 1st prize.[213][214]

- In 1855, Steinway exhibited at the American Institute Fair in the New York Crystal Palace in what is now Bryant Park in New York City. Steinway won a gold medal "for excellent quality". A reporter wrote the following: "Their square pianos are characterized by great power of tone, a depth and richness in the bass, a full mellowness in the middle register and brilliant purity in the treble, making a scale perfectly equal and singularly melodious throughout its entire range. In touch, they are all that could be desired."[215]

- From 1855 to 1862 Steinway pianos received 35 medals in the United States alone, since which time Steinway entered their pianos at international exhibitions only.[27][30]

- In 1862, for the International Exhibition in London, Steinway shipped two square pianos and two grand pianos to England (two to Liverpool and two to London) and won 1st prize.[30]

- In 1867, Steinway won three awards at the International Exposition in Paris: the Grand Gold Medal of Honor "for excellence in manufacturing and engineering pianos", the grand annual testimonial medal, and an honorary membership of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. These medals won in Europe increased the demand for Steinway pianos, thus the reason the family looked into opening a store in London. The International Exposition of 1867 established Steinway as the leading choice for pianos in Europe.[30][32]

- In 1876, at the famous Centennial Exposition in the United States, Steinway received the two highest awards and a certificate of the judges showing a rating of 95.5 of a possible 96.[216]

- In 1885, Steinway received the gold medal at the International Inventions Exhibition in London and the grand gold medal of the Royal Society of Arts in London.[24]

- In 2007, the National Medal of Arts was awarded to Henry Z. Steinway and presented by US President George W. Bush in an East Room ceremony at the White House. Henry Z. Steinway received the award for "his devotion to preserving and promoting quality craftsmanship and performance, as an arts patron and advocate for music and music education; and for continuing the fine tradition of the Steinway piano as an international symbol of American ingenuity and cultural excellence."[217] The National Medal of Arts is a presidential initiative managed by the National Endowment for the Arts.

- In 2014, Steinway received the Red Dot product design award for the Arabesque limited edition grand piano. The jury wrote: "The design of the Arabesque impresses through elegance and individuality. It thus excellently complements the high-class product line of this renowned manufacturing house."[218]

Patented inventions

Steinway has been granted 126 patents in piano making; the first patent was achieved in 1857.[33] Some notable examples of these are:

- Patent No. 26,532 (December 20, 1859):[219] The bass strings are "overstrung" above the treble strings to provide more length and better tonal quality. The invention won 1st prize medal at the 1862 International Exhibition in London.[220] Today, the invention is a standard feature of grand piano construction.[221]

- Patent No. 126,848 (May 14, 1872):[222] Steinway invented the duplex scale on the principle of enabling the freely oscillating parts of the string, directly in front of and behind the segment of the string actually struck, also to resound. The outcome is a large range and fullness of overtones – one of the characteristics of the Steinway sound.

- Patent No. 127,383 (May 28, 1872):[223] In a Steinway piano, the cast iron plate rests on wooden dowels without actually touching the soundboard. It is lightly curved, creating a large hollow between the plate and the soundboard. This cavity acts as a reinforcement of existing resonant properties. An additional function of the plate is to counteract the pull of more than 20 tons of the string tension.

- Patent No. 156,388 (October 27, 1874):[224] Steinway invented the middle piano pedal, called the sostenuto pedal. The sostenuto pedal gives the pianist an ability to create what is called an organ pedal point by keeping a specific note's damper, or notes' dampers, in their open position(s), allowing those strings to continue to sound while other notes can be played without continuing to resonate.

- Patent No. 170,645 (November 30, 1875):[225] Steinway's "regulation action pilot" – also known as the capstan screw, which lifts the parts that drive the hammer toward the string. The Steinway device was adjustable, an advance that simplifies the chore of modifying a piano's action to a pianist's liking. Henry Z. Steinway called that patent the birth of the modern grand piano action.[226]

- Patent No. 233,710 (October 26, 1880):[227] The bridge transmits the vibration of the strings to the soundboard. In a Steinway piano, the bridge consists of vertically glued laminations; a principle that ensures that vibrations are easily developed and forwarded.

- Patent No. 314,742 (March 31, 1885):[228] The inner and outer case comprise up to 18 layers of solid, hard-textured, horizontal-grain timber, pressed and bent into shape in one operation. They turn the case into one of the major components of the entire resonant body. It is a special bending process without the application of either heat or humidity.

- Patent No. 2,051,633 (August 18, 1936):[152] The soundboard resembles a membrane. The special molding, gradually tapering from the center to the edge, provides great flexibility and freer vibration across the board.

- Patent No. 3,091,149 (May 28, 1963):[229] The pin-block is specially designed to keep the instrument in tune longer. Steinway uses six glued layers of hard-textured wood, set at a 45° angle to the run of the grain. In this way, the tuning pins have a strong hold in the pin-block against overall pull and tension.

Documentary films

Note by Note: The Making of Steinway L1037

Note by Note: The Making of Steinway L1037 is an independent documentary film that follows the construction of a Steinway concert grand piano for more than a year, from the search for wood in Alaska to a display at Manhattan's Steinway Hall. The documentary film received its U.S. theatrical premiere at New York's Film Forum in November 2007.[230]

In the documentary, the pianists Pierre-Laurent Aimard, Kenny Barron, Bill Charlap, Harry Connick, Jr., Hélène Grimaud, Hank Jones, Lang Lang and Marcus Roberts, are seen testing and talking about Steinway pianos. The Steinway founder's great-grandson, Henry Z. Steinway, talks about the company's history.[231][232]

Critics gave the documentary mostly positive reviews. As of July 17, 2011[update], the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 90 percent of critics gave the film positive reviews, based on 20 reviews.[230]

Pianomania

Pianomania is a 2009 German-Austrian documentary film. The film presents Steinway's chief piano tuner and concert technician for the Vienna-area, Stefan Knüpfer, in his work with pianists such as Lang Lang, Alfred Brendel and Pierre-Laurent Aimard.[233]

The collaborative work between Stefan Knüpfer and Pierre-Laurent Aimard is at the center of the film. The Art of Fugue by Johann Sebastian Bach is to be recorded and the film gain insight into Stefan Knüpfer's work on the Steinway piano before and during the recording session. The film begins one year before the recording takes place.[234] One of Alfred Brendel's last concerts takes place at the Grafenegg Music Festival in Vienna. Stefan Knüpfer prepares the Steinway piano for him while Alfred Brendel gives his directions humorously.

Music

Steinway pianos have appeared in numerous records and concerts. A few examples include:

-

Ignacy Jan Paderewski performing on a Steinway[235] grand piano waltz in C sharp minor, Op. 64, No. 2, composed by Frédéric Chopin. (Studio recording from 1917).

-

Sergei Rachmaninoff performing on a Steinway[236] grand piano waltz in E flat major, Op. 18, composed by Frédéric Chopin. (Studio recording from 1921).

-

The White House's Steinway[69] art case grand piano from 1938. Lin-Manuel Miranda (rapping) and Alex Lacamoire (piano) performing The Hamilton Mixtape, composed by Lin-Manuel Miranda, at the White House Evening of Poetry, Music and the Spoken Word. (Concert recording from 2009).

-

Harry Connick, Jr. and his band performing When the Saints Go Marching In. Harry Connick, Jr. plays on a Steinway[237] grand piano. (Concert recording from 2010).

References

Notes

- ^ Fostle, Donald W. (1995). The Steinway Saga: An American Dynasty. New York: Scribner. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-684-19318-2.

- ^ Stevens, Mark A. (2000). Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Encyclopedia. Merriam-Webster. p. 1540. ISBN 978-0-87779-017-4.

- ^ a b c Fine, Larry (2014). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Fall 2014. Brookside Press LLC. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-192914539-3.

- ^ a b c "Steinway Musical Instruments 2012 Annual Report on Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. March 14, 2013. p. 5. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Steinway Grand Pianos". Steinway & Sons – Americas headquarters. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Grand Pianos". Steinway & Sons – Europe and worldwide headquarters. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Steinway Upright Pianos". Steinway & Sons – Americas headquarters. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ a b "Upright Pianos". Steinway & Sons – Europe and worldwide headquarters. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ "Carnegie Hall Congratulates Steinway & Sons on 160 Years of Greatness". Carnegie Hall. March 15, 2013. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Steinway Restoration Center". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Good, Edwin M. (2002). Giraffes, black dragons, and other pianos: a technological history from Cristofori to the modern concert grand. Stanford University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-8047-4549-9.

- ^ a b Panchyk, Richard (2008). German New York City. Arcadia Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-7385-5680-2.

- ^ a b c Michael Lenehan (2003) [1982]. "The Quality of the Instrument (K 2571 – The Making of a Steinway Grand)". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ "Now & Then". Steinway & Sons – Europe and worldwide headquarters. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ Steinway & Sons Documentary – A World of Excellence. Shanghai Hantang Culture Development Co., Ltd. July 3, 2013. Event occurs at 6:16. Retrieved March 14, 2015 – via Official YouTube channel of Steinway & Sons.

- ^ a b c d e Liebeskind, David (2003). "The Keys To Success". Stern Business – A publication of the Stern School of Business, New York University. Fall/Winter 2003 – "The Producers". New York: Stern School of Business, New York University: 10–15. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Giordano, Sr., Nicholas J. (2010). Physics of the Piano. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-954602-2.

- ^ Edmondson, Jacqueline (2006). Condoleezza Rice: A biography. The United States: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-313-33607-2.

- ^ Elliott, Alan C. (1998). A daily dose of the American dream: Stories of success, triumph and inspiration. The United States: Rutledge Hill Press. ISBN 978-1-55853-592-3.

- ^ Ehrlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-19-816171-4.

- ^ Derdak, Thomas; Grant, Tina (1997). International Directory of Company Histories. Vol. 19. St. James Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-1-55862-353-8.

- ^ a b Cummings, Thomas; Worley, Christopher (2014). Organization Development and Change. Cengage Learning. p. 102. ISBN 9781305143036.

- ^ a b c de Ocampo, Stuart (1997). "Review: The Steinway Saga: An American Dynasty by Donald W. Fostle; Steinway & Sons by Richard K. Lieberman". American Music. 15 (3): 409.

- ^ a b c Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ "Steinway & Sons". The Royal Warrant Holders Association. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Singer, Aaron (1986). Labor management relations at Steinway & Sons, 1853–1896. Garland. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8240-8371-7.

- ^ Spillane, Daniel (1892). "Musical Instruments – The Piano-Forte". The Popular Science Monthly. 40 (31). Bonnier Corporation: 488. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Kehl, Roy F.; Kirkland, David R. (2011). The Official Guide to Steinway Pianos. The United States: Amadeus Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-57467-198-8.

- ^ a b c d Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ a b Daniell, Charles A. (1895). Musical instruments at the World's Columbian Exposition. Chicago: Presto Co. p. 293.

- ^ a b c Robert C. Kennedy (August 10, 1867). "Sudden Mania to Become Pianists..." Harper's Weekly. Retrieved February 9, 2015. Cite error: The named reference "Steinway lithograph" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Kehl, Roy F.; Kirkland, David R. (2011). The Official Guide to Steinway Pianos. The United States: Amadeus Press. pp. 133–138. ISBN 978-1-57467-198-8.

- ^ a b c Fine, Larry (2014). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Fall 2014. Brookside Press LLC. p. 162. ISBN 978-192914539-3.

- ^ a b c Fine, Larry (2014). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Fall 2014. Brookside Press LLC. p. 166. ISBN 978-192914539-3.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ a b c d Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 23, 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Goldenberg, Susan (1996). Steinway: From glory to controversy; the family, the business, the piano. Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-88962-607-2.

- ^ "Steinway und Seesen" (in German). Stadtverwaltung Seesen. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Steinway, Theodore E. (2005). People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons (3rd ed.). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-57467-112-4.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ a b "Steinway & Sons' double victory – the truth at last" (PDF). The New York Times. December 5, 1876. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "Steinway's victory and laurels" (PDF). The New York Times. October 17, 1876. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Barron, James (2006). Piano: The Making of a Steinway Concert Grand. New York: Holt. pp. 102–109. ISBN 978-0-8050-7878-7.

- ^ Wolff, Isabel (February 15, 1997). "Lifting the lid on the Steinways". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ Steinway, Theodore E. (2005). People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons (3rd ed.). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-57467-112-4.

- ^ Beckert, Sven (2003). The Monied Metropolis: New York City and the Consolidation of the American Bourgeoisie, 1850–1896. Cambridge University Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 9780521524100.

- ^ a b Wainwright, David (1975). The Piano Makers. Humanities Pr. p. 119. ISBN 978-0091229504.

- ^ Loesser, Arthur (1954). Men, Women and Pianos: A social History. University of California. p. 553. ISBN 978-0-486-26543-8.

- ^ Goldenberg, Susan (1996). Steinway: From glory to controversy; the family, the business, the piano. Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-88962-607-2.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ "Steinway Hall's Final Movement Begins Following $131 M. Sale". Commercial Observer, The New York Observer. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Hall: Center of the Piano Universe". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ James Barron (October 29, 2014). "Changing Keys, Steinway Piano Store Will Relocate in Midtown". The New York Times. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Hall Manhattan New York City". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Hall London". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway-Haus Berlin" (in German). Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway-Haus Wien (Vienna)" (in German). Steinway in Austria. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ a b "Treasures of the White House". The White House Historical Association. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Distler, Jed (Spring 2010). "Casing the Piano". Listen: Life with Music & Culture. Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Prettejohn, Elizabeth (March 1, 2002). "Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the modern city of ancient Rome". The Art Bulletin.

- ^ a b Paul Gambaccini (September 29, 2011). "Playing the White House: Entertaining with the US president". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Lin-Manuel Miranda Performs at the White House Poetry Jam: 8 of 8". The White House. May 12, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ James Barron (April 2, 2004). "A Piano Is Born, Needing Practice; Full Grandness of K0862 May Take Several Concerts to Achieve". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ James Barron (July 15, 2007). "Let's Play Two: Singular Piano". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 49–55. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Tom Hundley (April 30, 2008). "Aftermath favored Steinway". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ MacMahon, Lloyd Francis (October 1, 1973). "Grotrian v. Steinway & Sons". United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Rothman, Jennifer E. (October 2005). "Initial Interest Confusion: Standing at the Crossroads of Trademark Law" (PDF). Cardozo Law Review. 27 (1). Yeshiva University: 114–116. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Yu, Peter K. (2007). Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Trademark and Unfair Competition. Intellectual Property and Information Wealth: Issues and Practices in the Digital Age. Vol. 3. Praeger Publishers, Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 87–88. ISBN 0-275-98885-6.

- ^ Kornblith, Gary John (1999). "Steinway & Sons (review)". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 30 (1): 148–149.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ a b Giordano, Sr., Nicholas J. (2010). Physics of the Piano. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-19-954602-2.

- ^ Reuters (September 14, 1985). "CBS Steinway Sale". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 308. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ a b Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ Broyles, Michael (2011). Beethoven in America. The United States: Indiana University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-0-253-35704-5.

- ^ Fine, Larry (2014). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Fall 2014. Brookside Press LLC. p. 194. ISBN 978-192914539-3.

- ^ Kopf, Silas (2008). A marquetry odyssey: Historical objects and personal work. Hudson Hills. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-55595-287-7.

- ^ Carr, Elizabeth (2006). Shura Cherkassky: The Piano's Last Czar. Scarecrow Press, Inc. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8108-5410-9.

- ^ "DeVoe Moore adds world-famous Steinway to his museum". Tallahassee Democrat. December 4, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway & Sons History". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b "What is Excellence?". Lyra – The Music Magazine. 2. Steinway & Sons – Europe and worldwide headquarters: 9. 2007.

- ^ Joe Mont (October 18, 2011). "10 Things Still Made in America". MainStreet. TheStreet, Inc. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Kehl, Roy F.; Kirkland, David R. (2011). The Official Guide to Steinway Pianos. The United States: Amadeus Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-1-57467-198-8.

- ^ "Steinway & Sons History". Theme and Variations Piano Services. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "Legendary Piano Maker Steinway & Sons Commemorates 150th Anniversary". Business Wire. March 5, 2003. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c Steinway, Theodore E. (2005). People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons (3rd ed.). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-57467-112-4.

- ^ a b "The 125th Anniversary". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Diane Cole (June 6, 2003). "Fanfare for the Uncommon Piano". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ James Barron (September 18, 2008). "Henry Z. Steinway, Piano Maker, Dies at 93". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Classical music for inauguration was taped, not live". USA Today. January 23, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Inauguration pianist: 'We did the right thing'". USA Today. January 27, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Diane Greer (May 2009). "Songs in the Key of Green – Piano Manufacturer Installs World's Largest Rooftop Solar Thermal Array". New York Construction News, The McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ James Barron (December 26, 2008). "Coming Soon at Steinway, Solar Power". The New York Times. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ a b Neudorf, Paula; Soon, Weilun. "Recession's Impact". The Last American Grand. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Musical Instruments 2010 Annual Report on Form 10-K" (PDF). Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. March 14, 2011. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Musical Instruments 2011 Annual Report on Form 10-K" (PDF). Steinway Musical Instruments, Inc. March 14, 2012. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 4, 2013. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Kehl, Roy F.; Kirkland, David R. (2011). The Official Guide to Steinway Pianos. The United States: Amadeus Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-57467-198-8.

- ^ a b c Amy Sciarretto (November 2, 2010). "Steinway & Sons Introduce the Imagine Series Limited Edition Piano". ARTISTdirect. Rogue Digital, LLC. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "John Lennon: Imagine Peace". Yoko Ono's official YouTube channel. September 22, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Lady Gaga angers Beatles fans by playing John Lennon's piano". Daily Mail, Associated Newspapers Ltd. July 10, 2010. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "Steinway Hall Announces the John Lennon Imagine Series Limited Edition Piano Tour". Ellenwood-EP.com, LLC. August 2, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "John Lennon wrote Imagine on his white Steinway. What would you write on yours?". Daily Mail, Associated Newspapers Ltd. July 23, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Maria Ajit Thomas (July 1, 2013). "Kohlberg to buy grand piano maker Steinway for $438 million". Reuters. Retrieved February 14, 2015.

- ^ Ring, Niamh; Murphy, Lauren S.; Klein, Jodi Xu (August 14, 2013). "Steinway Agrees to Be Bought by Paulson for $512 Million". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Greene, Kerima (October 8, 2013). "For John Paulson, Steinway deal means more than profits". CNBC LLC. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall: An Artist's Country Estate". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Frelinghuysen, Alice Cooney; Monica, Monica. "Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall". Antiques and Fine Art. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 156 and 158. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ a b c "Designed by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Model D Pianoforte and Stools". Clark Art Institute. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Steinway & Sons – Art Case Pianos". The Exclusive Piano Group. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "Steinways". The Guardian. June 6, 2003. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Mohit Joshi (May 11, 2008). "Steinway & Sons unveils most expensive piano". Topnews. Manas Informatics Pvt. Ltd. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "November: 'Art' piano is Expo musical key". Shme – Today's Shanghai. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "150th Anniversary". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "William E. Steinway". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ "The Steinway Crown Jewels. A Sought After Musical Gem". Eat Love Savor. Tunner Media. January 20, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Barron, James (2006). Piano: The Making of a Steinway Concert Grand. New York: Holt. p. 238. ISBN 978-0-8050-7878-7.

- ^ Steinway, Theodore E. (2005). People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons (3rd ed.). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-57467-112-4.

- ^ "Steinway Musical Instruments 2012 Annual Report on Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. March 14, 2013. p. 3. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Steinway Musical Instruments 2012 Annual Report on Form 10-K". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. March 14, 2013. p. 6. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Mohr, Franz; Schaeffer, Edith (1996). My Life with the Great Pianists (2nd ed.). Baker Books. p. 50. ISBN 9-780801-057106.

- ^ "An enduring Classic – Steinway & Sons: History in the Playing". Steinway & Sons 150th Anniversary Official Publication. Faircount Ltd.: 32 2003.

- ^ a b c James Barron (August 27, 2003). "Steinways With German Accents; Pianos Made in Queens Have Cousins in Hamburg". The New York Times. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Fine, Larry (2014). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Fall 2014. Brookside Press LLC. pp. 40 and 42. ISBN 978-192914539-3. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Emanuel Ax". The Juilliard School. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Fine, Larry (2012). Acoustic & Digital Piano Buyer – Spring 2012. Brookside Press LLC. p. 195. ISBN 978-192914533-1.

- ^ Hahn, Steve. "Steinway & Sons: Applying LeanSigma® to the Art of Piano-Making" (PDF). TBM Consulting Group. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ Stewart, Jude (2003). "Just about perfect: The dichotomy of Steinway piano design". STEP Inside Design. 19 (November/December): 68.

- ^ Bambarger, Bradley (Spring 2011). "Instrumental Royalty". Listen: Life with Music & Culture. Steinway & Sons. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- ^ Barron, James (2006). Piano: The Making of a Steinway Concert Grand. New York: Holt. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8050-7878-7.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.

- ^ "A Quality Piano Starts with Quality Wood". Steinway Hall – Dallas/Fort Worth/Plano. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Barron, James (2006). Piano: The Making of a Steinway Concert Grand. New York: Holt. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-8050-7878-7.

- ^ "Rim Bending Process". Steinway Hall – Dallas/Fort Worth/Plano. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ "How Products Are Made". Advameg, Inc. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ "Coming Together: Fitting The Soundboard & Plate to the Pianos Rim". Steinway Hall – Dallas/Fort Worth/Plano. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f E.g.: "Model D – Technical Specifications". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ Steinway & Sons Documentary – A World of Excellence. Shanghai Hantang Culture Development Co., Ltd. July 3, 2013. Event occurs at 12:41. Retrieved March 14, 2015 – via Official YouTube channel of Steinway & Sons.

- ^ Goldenberg, Susan (1996). Steinway: From glory to controversy; the family, the business, the piano. Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-88962-607-2.

- ^ "The Steinway Soundboard". Steinway Hall – Dallas/Fort Worth/Plano. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Patent number: 2,051,633". Google Patent Search. Google. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Mohr, Franz; Schaeffer, Edith (1996). My Life with the Great Pianists (2nd ed.). Baker Books. p. 104. ISBN 9-780801-057106.

- ^ "Piano Keys / The Steinway Piano Keyboard". Michael Sweeney Piano Craftsman. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ Loesser, Arthur (1954). Men, Women and Pianos: A social History. University of California. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-486-26543-8.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ "The Hall of Legends". Steinway & Sons 150th Anniversary Official Publication. Faircount Ltd.: 80 2003.

- ^ Lieberman, Richard K. (1995). Steinway & Sons. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-300-06364-6.

- ^ "Steinway Artists". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ "Piano manufacturers – Making the sound of music". The Economist. 367 (8327–8330). The Economist Newspaper Limited: 78. June 7, 2003.

- ^ Steinway, Theodore E. (2005). People and Pianos: A Pictorial History of Steinway & Sons (3rd ed.). Pompton Plains, New Jersey: Amadeus Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-57467-112-4.

- ^ a b Wilson, Cynthia (2011). Always Something New to Discover: Menahem Pressler and the Beaux Arts Trio. Paragon Publishing. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-908341-25-9.

- ^ "Daniel Barenboim". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Harry Connick, Jr". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Billy Joel". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Evgeny Kissin". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Diana Krall". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Lang Lang". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Giordano, Sr., Nicholas J. (2010). Physics of the Piano. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-19-954602-2.

- ^ "Benjamin Britten". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Immortals". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Vladimir Horowitz". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Sergei Rachmaninoff". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "Ensembles". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Katia & Marielle Labèque". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "The 5 Browns". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Young Steinway Artists". Steinway & Sons. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

- ^ Kjemtrup, Inge (2010). "Helping tomorrow's stars today". Steinway & Sons – Owners' Magazine. 2. Faircount Media Group: 22–28.

- ^ a b c d e f "MUSIC; Piano Versus Piano". The New York Times. May 9, 2004. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Schnabel, Artur (1988). My Life and Music. Dover Publications and Colin Smythe. pp. 84 and 111. ISBN 0-486-25571-9.

- ^ Ward, Brendan (2013). "24: Revealing the piano's full set of teeths". The Beethoven Obsession. University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-1742233956.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Ronald V. (2002). Steinway. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8118-3389-9.