LGBTQ people and Islam

LGBT and Islam is influenced by the religious, legal and cultural history of the nations with a sizable Muslim population, along with specific passages in the Quran[1][2] and statements attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad (hadith). Hadiths traditionally are not interpreted because their language is understood to be simple matter-of-fact language. Orthodox Islam is not only a system of beliefs, but also a legal system.

The traditional schools of Islamic law based on Quranic verses and hadith consider homosexual acts a punishable crime and a sin, and influenced by Islamic scholars such as Imam Malik and Imam Shafi.[3] The Qur'an cites the story of the "people of Lot" destroyed by the wrath of God because they engaged in "lustful" carnal acts between men. Nevertheless, homoerotic themes were present in poetry and other literature written by some Muslims from the medieval period onwards and sometimes homoeroticism in the form of pederasty was seen in a positive way.[4]

Extreme prejudice remains, both socially and legally, in much of the Islamic world against people who engage in homosexual acts. In Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Mauritania, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, United Arab Emirates and Yemen, homosexual activity carries the death penalty.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11] In others, such as Algeria, Maldives, Malaysia, Qatar, Somalia and Syria, it is illegal.[12][13][14][15] Same-sex sexual intercourse is legal in 20 Muslim-majority nations (Albania, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Guinea-Bissau, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Niger, Tajikistan, Turkey, West Bank (State of Palestine), and most of Indonesia (except in Aceh and South Sumatra provinces, where bylaws against LGBT rights have been passed), as well as Northern Cyprus).[16][17] In Albania, Lebanon, and Turkey, there have been discussions about legalizing same-sex marriage.[18][19] Homosexual relations between females are legal in Kuwait and Uzbekistan, but homosexual acts between males are illegal.[20][21][22][16]

Most Muslim-majority countries and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) have opposed moves to advance LGBT rights at the United Nations, in the General Assembly and/or the UNHRC. In May 2016, a group of 51 Muslim states blocked 11 gay and transgender organizations from attending 2016 High Level Meeting on Ending AIDS.[23][24][25][26] However, Albania, Guinea-Bissau and Sierra Leone have signed a UN Declaration supporting LGBT rights.[27][28] Albania provide LGBT rights protections in law in the form of non-discrimination laws, and discussions on legally recognizing same-sex marriage have been held in the country.[citation needed] Kosovo as well as the (internationally not recognized) Muslim-majority Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus also have anti-discrimination laws in place.

Scripture and Islamic jurisprudence

The Quran

The Quran contains seven references to fate of "the people of Lut", and their destruction by Allah is associated explicitly with their sexual practices:[29][30][31]

"And (We sent) Lot when he said to his people: What! do you commit an indecency which any one in the world has not done before you? Most surely you come to males in lust besides females; nay you are an extravagant people. And the answer of his people was no other than that they said: Turn them out of your town, surely they are a people who seek to purify (themselves). So We delivered him and his followers, except his wife; she was of those who remained behind. And We rained upon them a rain; consider then what was the end of the guilty."[7:80–84 (Translated by Shakir)]

The sins of the people of Lut (Arabic: لوط) became proverbial, and the Arabic words for homosexual behaviour (Arabic: لواط, romanized: liwāṭ) and for a person who performs such acts (Arabic: لوطي, romanized: lūṭi) both derive from his name.[32] The story of Lut is used to demonstrate how homosexuality is based in non-consent between the men. However, some scholars[who?] of Islam argue that the foundation of homosexual discourse in Islam cannot be rooted in consent because there are many more instances in the Quran in which there is no consent between partners. With this, sexual acts between men and youth are not considered transgressive.

Only one passage in the Qur'an prescribes a strictly legal position. It is not restricted to homosexual behaviour, however, and deals more generally with public practice of adultery:[33]

"And as for those who are guilty of an indecency from among your women, call to witnesses against them four (witnesses) from among you; then if they bear witness confine them to the houses until death takes them away or Allah opens some way for them. And as for the two who are guilty of indecency from among you, give them both a punishment; then if they repent and amend, turn aside from them; surely Allah is oft-returning (to mercy), the Merciful."[4:15–16 (Translated by Shakir)]

Because the Quran is also a legal document, there are several major sins outlined in the text. Two of these consider sexual misconduct. They are Zina and Liwat.[2] Zina literally means "adultery". It is "sex between a man and a woman who is neither his wife nor his slave—the most serious of sexual transgressions described in the Qur'an".[2] Liwat is "anal intercourse between men or anal sex between a male and a female 'stranger'—that is, a woman who is neither his wife nor his slave over whom he has no sexual rights". The issue of homosexuality comes more from a standpoint of legal sexual rights.[2]

According to the laws of Shariah, Muslims found guilty of homosexual acts should repent rather than confess. This means that many Muslim countries tolerate same-sex acts so long as they happen in private and do not challenge the existing dominant family and social order.[34] Many Muslim scholars have followed this idea of a "don't ask, don't tell" policy in regards to homosexuality in Islam, by treating the subject with passivity.[2] Comparisons have been made between the imperative nature of the secrecy of homosexual acts and the secrecy of women in many Islamic societies. In other words, women have to live under a certain amount of secrecy (whether that means being veiled or otherwise), and homosexuals must keep all of their transgressions and acts a secret.

There were varying opinions on how the death penalty was to be carried out. Abu Bakr apparently recommended toppling a wall on the evil-doer, or else burning alive,[35] while Ali bin Abi Talib ordered death by stoning for one "luti" and had another thrown head-first from the top of a minaret—according to Ibn Abbas, this last punishment must be followed by stoning.[36]

The Hadith and Seerah

The hadith (sayings and actions of Muhammad) show that homosexuality was not unknown in Arabia.[36] Given that the Qur'an is allegedly vague regarding the punishment of homosexual sodomy, Islamic jurists turned to the collections of the hadith and seerah (accounts of Muhammad's life) to support their argument for Hudud punishment.[36]

Abu `Isa Muhammad ibn `Isa at-Tirmidhi compiling the Sunan al-Tirmidhi around C.E.884 (two centuries after the death of Muhammad) wrote that Muhammad had prescribed the death penalty for both the active and the passive partner:

Narrated by Abdullah ibn Abbas: The Prophet (peace be upon him) said: If you find anyone doing as Lot's people did, kill the one who does it, and the one to whom it is done.

The overall moral or theological principle is that a person who performs such actions (luti) challenges the harmony of God's creation, and is therefore a revolt against God.[32]

Ibn al-Jawzi (1114-1200) writing in the 12th century claimed that Muhammad had cursed "sodomites" in several hadith, and had recommended the death penalty for both the active and passive partners in homosexual acts.[37]

Al-Nuwayri (1272-1332) in his Nihaya reports that Muhammad is alleged to have said what he feared most for his community were the practices of the people of Lot (although he seems to have expressed the same idea in regard to wine and female seduction).[36]

The following tradition also speaks to non-traditional gender behavior:

Narrated by Abdullah ibn Abbas: The Prophet cursed effeminate men; those men who are in the similitude (assume the manners of women) and those women who assume the manners of men, and he said, "Turn them out of your houses." The Prophet turned out such-and-such man, and 'Umar turned out such-and-such woman.

Later medieval jurisprudence

The four schools of shari'a (Islamic law) disagreed on what punishment is appropriate for liwat. Abu Bakr Al-Jassas (d. 981 AD/370 AH) argued that the two hadiths on killing homosexuals "are not reliable by any means and no legal punishment can be prescribed based on them",[38] and the Hanafi school held that it does not merit any capital punishment, on the basis of a hadith that "Muslim blood can only be spilled for adultery, apostasy and homicide"; against this the Hanbali school inferred that sodomy is a form of adultery and must incur the same penalty, i.e. death.[32][page needed]

Modern legal views

With few exceptions all scholars of Sharia, or Islamic law, interpret homosexual activity as a punishable offence as well as a sin. There is no specific punishment prescribed, however, and this is usually left to the discretion of the local authorities on Islam.[39] Mohamed El-Moctar El-Shinqiti, a contemporary Mauritanian scholar, has argued that "[even though] homosexuality is a grievous sin...[a] no legal punishment is stated in the Qur'an for homosexuality...[b] it is not reported that Prophet Muhammad has punished somebody for committing homosexuality...[c] there is no authentic hadith reported from the Prophet prescribing a punishment for the homosexuals..." Hadith scholars such as Al-Bukhari, Yahya ibn Ma'in, Al-Nasa'i, Ibn Hazm, Al-Tirmidhi, and others have impugned these statements.[40]

Faisal Kutty, a professor of Islamic law at Indiana-based Valparaiso University Law School and Toronto-based Osgoode Hall Law School, commented on the contemporary same-sex marriage debate in a March 27, 2014 essay in the Huffington Post.[41] He acknowledged that while Islamic law iterations prohibits pre- and extra-marital as well as same-sex sexual activity, it does not attempt to "regulate feelings, emotions and urges, but only its translation into action that authorities had declared unlawful". Kutty, who teaches comparative law and legal reasoning, also wrote that many Islamic scholars [42] have "even argued that homosexual tendencies themselves were not haram [prohibited] but had to be suppressed for the public good". He claimed that this may not be "what the LGBTQ community wants to hear", but that, "it reveals that even classical Islamic jurists struggled with this issue and had a more sophisticated attitude than many contemporary Muslims". Kutty, who in the past wrote in support of allowing Islamic principles in dispute resolution, also noted that "most Muslims have no problem extending full human rights to those—even Muslims—who live together 'in sin'". He argued that it therefore seems hypocritical to deny fundamental rights to same-sex couples. Moreover, he concurred with Islamic legal scholar Mohamed Fadel[43] in arguing that this is not about changing Islamic marriage (nikah), but about making "sure that all citizens have access to the same kinds of public benefits".

Islamist journalist Muhammad Jalal Kishk found no prescribed punishment for homosexuality in Islamic law[44][full citation needed][45] Several modern day scholars, including Scott Kugle, argue for a different interpretation of the Lot narrative focusing not on the sexual act but on the infidelity of the tribe and their rejection of Lot's Prophethood.[46]

There are several methods by which sharia jurists have advocated the punishment of gays or lesbians who are sexually active. One form of execution involves an individual convicted of homosexual acts being stoned to death by a crowd of Muslims.[47][page needed] Other Muslim jurists have established ijma ruling that those committing homosexual acts be thrown from rooftops or high places,[48] and this is the perspective of most Salafists.[49]

History of homosexuality in Islamic societies

Medieval era

The centuries immediately after Muhammad's death led to a rapid growth of the Islamic empire accompanied by increased prosperity. Some Muslims bemoaned the general "corruption" of morals in the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and it's clear that homosexual practice continued (in a subterranean manner) despite its growing condemnation by the religious authorities. In fact, it seems to have become less hidden as the process of acculturation sped up, such as in the area of music and dance where mukhannathun were prevalent. The arrival of the Abbasid army to Arabia in the 8th century seems to have meant that tolerance for homosexual practice subsequently spread even more widely under the new dynasty. The ruler Al-Amin (809-813), for example, was said to have required slave women to be dressed in masculine clothing so he could be persuaded to have sex and produce an heir.[36] Abu Nuwas (756-814), born in the city of Ahvaz in modern-day Iran, became a master of all the contemporary genres of Arabic poetry; sharing Al-Amin's love for men and composing poems celebrating such love.[50]

There are other examples from the following centuries. The Aghlabid Emir, Ibrahim II of Ifriqiya (ruled 875–902), was said to have been surrounded by some sixty catamites, yet whom he was said to have treated in a most horrific manner. Caliph al-Mutasim in the 9th century and some of his successors were accused of homosexuality. The popular stories says that Cordoba, Abd al-Rahman III had executed a young man from León who was held as a hostage, because he had refused his advances during the Reconquista.[36]

Mahmud of Ghazni (971-1030), the ruler of the Ghaznavid Empire, had a Turkish slave named Malik Ayaz as a companion. Their relationship inspired poems and stories.[51][52]

Mehmed the Conqueror, the Ottoman sultan living in the 15th century, European sources say "who was known to have ambivalent sexual tastes, sent a eunuch to the house of Notaras, demanding that he supply his good looking fourteen year old son for the Sultan’s pleasure. When he refused, the Sultan instantly ordered the decapitation of Notaras, together with that of his son and his son-in-law; and their three heads … were placed on the banqueting table before him".[53] Another youth Mehmed found attractive, and who was presumably more accommodating, was Radu III the Fair, the brother of the famous Vlad the Impaler, "Radu, a hostage in Istanbul whose good looks had caught the Sultan’s fancy, and who was thus singled out to serve as one of his most favored pages." After the defeat of Vlad, Mehmed placed Radu on the throne of Wallachia as a vassal ruler. However, Turkish sources deny these stories.[54]

According to the Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World:

Whatever the legal strictures on sexual activity, the positive expression of male homeoerotic sentiment in literature was accepted, and assiduously cultivated, from the late eighth century until modern times. First in Arabic, but later also in Persian, Turkish and Urdu, love poetry by men about boys more than competed with that about women, it overwhelmed it. Anecdotal literature reinforces this impression of general societal acceptance of the public celebration of male-male love (which hostile Western caricatures of Islamic societies in medieval and early modern times simply exaggerate).[55]

European travellers remarked on the taste that Shah Abbas of Iran (1588-1629) had for wine and festivities, but also for charming pages and cup bearers. A painting by Riza Abbasi with homo-erotic qualities shows the ruler enjoying such delights.[56]

Modern era

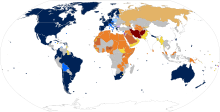

| | Neither | States which did not support either declaration |

| | Non-member states | States that are not voting members of the United Nations |

| | Oppose | States which supported an opposing declaration in 2008 and continued their opposition in 2011 |

| | Subsequent member | South Sudan, did not exist in 2008 |

| | Support | States which supported the LGBT rights declaration in the General Assembly or on the Human Rights Council in 2008 or 2011 |

During the Ottoman Empire, homosexuality was decriminalized in 1858, as part of wider reforms during the Tanzimat.[57][58]

Pederasty

Despite the formal disapproval of religious authority, the segregation of women in Muslim societies and the strong emphasis on male virility leads adolescent males and unmarried young men to seek sexual outlets with boys younger than themselves—in one study in Morocco, with boys in the age-range 7 to 13.[59] Men have sex with other males so long as they are the penetrators and their partners are boys, or in some cases effeminate men.[60]

Liwat can therefore be regarded as "temptation",[61] and anal intercourse is not seen as repulsively unnatural so much as dangerously attractive. They believe "one has to avoid getting buggered precisely in order not to acquire a taste for it and thus become addicted."[62] Not all sodomy is homosexual: one Moroccan sociologist, in a study of sex education in his native country, notes that for many young men heterosexual sodomy is considered better than vaginal penetration, and female prostitutes likewise report the demand for anal penetration from their (male) clients.[63]

It is not so much the penetration as the enjoyment that is considered bad.[64] Deep shame attaches to the passive partner: "for this reason men stop getting laid at the age of 15 or 16 and 'forget' that they ever allowed it earlier." Similar sexual sociologies are reported for other Muslim societies from North Africa to Pakistan and the Far East.[65] In Afghanistan in 2009, the British Army was forced to commission a report into the sexuality of the local men after British soldiers reported the discomfort at witnessing adult males involved in sexual relations with boys. The report stated that though illegal, there was a tradition of such relationships in the country, known as "bache bazi" or boy play, and that it was especially strong around North Afghanistan.[66]

Homosexuality laws in majority-Muslim countries

Criminalized

According to the International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA) seven countries still retain capital punishment for homosexual behavior: Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iran, Afghanistan, Mauritania, Sudan, and northern Nigeria.[67][68] In United Arab Emirates it is a capital offense.[69][11] In Qatar, Algeria, Uzbekistan, and the Maldives, homosexuality is punished with time in prison or a fine. This has led to controversy regarding Qatar, which is due to stage the 2022 FIFA World Cup. Human rights groups have questioned the awarding in 2010 of the right to host the competition, due to the possibility that gay football fans may be jailed. In response, Sepp Blatter, head of FIFA, joked that they would have to "refrain from sexual activity" while in Qatar. He later withdrew the remarks after condemnation from rights groups.[70]

In Egypt, openly gay men have been prosecuted under general public morality laws. (See Cairo 52.) In Saudi Arabia, the maximum punishment for homosexual acts is public execution, which is often carried out.[71] The government will sometimes use lesser punishments—for example, fines, time in prison, and whipping—as alternatives.

Islamic state has decreed capital punishment for gays. They have executed 36 men for homosexual activity including several thrown off the top of 100 foot buildings in highly publicized executions. [72]

In India, which has the third largest Muslim population in the world, and where Muslims form a large minority, the largest Islamic seminary (Darul Uloom Deoband) has vehemently opposed recent government moves[73] to abrogate and liberalize laws from the British Raj era that banned homosexuality.[74]

Legal

However, in 20 out of 57 Muslim-majority nations same-sex intercourse is not forbidden by law.

The Ottoman Empire (predecessor of Turkey) decriminalized homosexuality in 1858. In Turkey, where 99.8% of the population is Muslim, homosexuality has never been criminalized since the day it was founded in 1923.[75] And LGBT people also have the right to seek asylum in Turkey under the Geneva Convention since 1951.[76]

Same-sex sexual intercourse is legal in Albania, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti, Guinea-Bissau, Lebanon, Iraq (except those parts controlled by Islamic State , Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Niger, Tajikistan, Turkey, West Bank (State of Palestine), most of Indonesia, and in Northern Cyprus. In Albania, Lebanon, and Turkey, there have been discussions about legalizing same-sex marriage.[18][19] Albania, Northern Cyprus and Kosovo also protect LGBT people with anti-discrimination laws.[77]

Same-sex marriage

In 2007 there was a gay party in the Moroccan town of al-Qasr al-Kabir. Rumours spread that this was a gay marriage and more than 600 people took to the streets, condemning the alleged event and protesting against leniency towards homosexuals.[78] Several persons who attended the party were detained and eventually six Moroccan men were sentenced to between four and ten months in prison for "homosexuality".[79]

In France there was an Islamic same-sex marriage on February 18, 2012.[80] In Paris in November 2012 a room in a Buddhist prayer hall was used by gay Muslims and called a "gay-friendly mosque",[81] and a French Islamic website [82] is supporting religious same-sex marriage.

The first American Muslim in the United States Congress, Keith Ellison (D-MN) said in 2010 that all discrimination against LGBT people is wrong.[83] He further expressed support for gay marriage stating:[84]

I believe that the right to marry someone who you please is so fundamental it should not be subject to popular approval any more than we should vote on whether blacks should be allowed to sit in the front of the bus.

In 2014 eight men were jailed for three years by a Cairo court after the circulation of a video of them allegedly taking part in a private wedding ceremony between two men on a boat on the Nile.[85]

Islamic extremist attacks targeting LGBT people

Radical Islam frequently attempts to incite followers to carry out violent attacks against members of the LGBT community:

- December 31, 2013 - New Year's Eve arson attack on gay nightclub packed with 300+ revelers, but no one injured. Subject charged prosecuted under federal terror and hate-crime charges. [86]

- February 12, 2016 - Across Europe, gay refugees facing abuse at migrant asylum shelters are forced to flee shelters. [87]

- June 12, 2016 - At least 49 people were killed and 50 injured in a mass shooting at a nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The shooter, Omar Mateen, pledged allegiance to ISIL.[88][89]

Public opinion among Muslims

In 2011, the UN Human Rights Council passed its first resolution recognizing LGBT rights, which was followed up with a report from the UN Human Rights Commission documenting violations of the rights of LGBT people.[90][91] The two world maps of religions of the world and the countries that support LGBT rights at the UN give an impression of the attitude towards homosexuality on the part of many Muslim-majority governments.

The Muslim community as a whole, worldwide, has become polarized on the subject of homosexuality. There is somewhat of a consensus, though, that "individuals bear moral responsibility for any sexual acts that they engage in by free choice and that illicit desires themselves do not result in any culpability before God."[2]

Opinion polls

In 2013, the Pew Research Center conducted a study on the global acceptance of homosexuality and found a widespread rejection of homosexuality in many nations that are predominantly Muslim. In some countries, views were actually becoming more conservative among younger people.[92]

| Country | 18-29 | 30-49 | 50+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homosexuality

should be accepted |

% | % | % |

| Malaysia | 7 | 10 | 11 |

| Turkey | 7 | 9 | 10 |

| Palestinian territories | 5 | 3 | -- |

| Indonesia | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Jordan | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Egypt | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Tunisia | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Pakistan | 2 | 2 | 2 |

- Source: "The Global Divide on Homosexuality" (Website). PEW Research. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

A 2007 survey of British Muslims showed that 61% believe homosexuality should be illegal, with up to 71% of young British Muslims holding this belief.[93] A later Gallup poll in 2009 showed that none of the 500 British Muslims polled believed homosexuality to be "morally acceptable". This compared with 35% of the 1001 French Muslims polled that did.[94]

According to a 2012 poll, 51% of the Turks in Germany, who account for nearly two thirds of the total Muslim population in Germany,[95] believe that homosexuality is an illness.[96]

LGBT movements within Islam

The Al-Fatiha Foundation was an organization which tried to advance the cause of gay, lesbian, and transgender Muslims. It was founded in 1998 by Faisal Alam, a Pakistani American, and was registered as a nonprofit organization in the United States. The organization was an offshoot of an internet listserve that brought together many gay, lesbian and questioning Muslims from various countries.[97][verification needed] The Foundation accepted and considered homosexuality as natural, either regarding Qur'anic verses as obsolete in the context of modern society, or stating that the Qu'ran speaks out against homosexual lust and is silent on homosexual love. After the Alam stepped down, subsequent leaders failed to sustain the organization and it began a process of legal dissolution in 2011.[98][non-primary source needed]

In 2001, Al-Muhajiroun, a banned and now defunct international organization who sought the establishment of a global Islamic caliphate, issued a fatwa declaring that all members of Al-Fatiha were murtadd, or apostates, and condemning them to death. Because of the threat and coming from conservative societies, many members of the foundation's site still prefer to be anonymous so as to protect their identity while continuing a tradition of secrecy.[99] Al-Fatiha has fourteen chapters in the United States, as well as offices in England, Canada, Spain, Turkey, and South Africa. In addition, Imaan, a social support group for Muslim LGBT people and their families, exists in the UK.[100][non-primary source needed] Both of these groups were founded by gay Pakistani activists. The UK also has the Safra Project for women.

Some Muslims, such as the lesbian writer Irshad Manji[citation needed] and academic author Scott Kugle, argue that Islam does not condemn homosexuality.[citation needed] He, as well as South Asian scholar and author Ruth Vanita and Muslim scholar and writer Saleem Kidwai, contend that ancient Islam has a rich history of homoerotic literature.[citation needed]

There are also a number of Islamic ex-gay (i.e. people claiming to have experienced a basic change in sexual orientation from exclusive homosexuality to exclusive heterosexuality)[101] groups aimed at attempting to guide homosexuals towards heterosexuality. A large body of research and global scientific consensus indicates that being gay, lesbian, or bisexual is compatible with normal mental health and social adjustment. Because of this, major mental health professional organizations discourage and caution individuals against attempting to change their sexual orientation to heterosexual, and warn that attempting to do so can be harmful.[102][103] People who have gone through conversion therapy face 8.9 times the rates of suicide ideation, face depression at 5.9 times the rate of their peers and are three times more likely to use illegal drugs compared to those who did not go through the therapy.[104]

The religious conflicts and inner turmoil that Islamic homosexuals struggle over has been addressed in various media, such as the 2006 Channel 4 documentary Gay Muslims, and the 2007 documentary film A Jihad for Love. The latter was produced by Sandi Simcha DuBowski, who six years earlier made a Jewish-themed documentary on the same topic, titled Trembling Before G-d.

In November 2012, a prayer room was set up in Paris by gay Islamic scholar and founder of the group 'Homosexual Muslims of France' Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed. It was described by the press as the first gay-friendly mosque in Europe. The reaction from the rest of the Muslim community in France has been mixed, the opening has been condemned by the Grand Mosque of Paris.[105]

Imam Nur Wahrsage has been an advocate for LGBTI Muslims and founded Marhaba, a support group for queer Muslims in Melbourne, Australia. In May 2016, Wahrsage revealed that he is homosexual in an interview on SBS2’s The Feed, being the first openly gay Imam in Australia.[106]

Gender variant and transgender people

In Islam, the term mukhannathun is used to describe gender-variant people, usually male-to-female transgender. Neither this term nor the equivalent for "eunuch" occurs in the Qur'an, but the term does appear in the Hadith, the sayings of Muhammad, which have a secondary status to the central text. Moreover, within Islam, there is a tradition on the elaboration and refinement of extended religious doctrines through scholarship. This doctrine contains a passage by the scholar and hadith collector An-Nawawi:

A mukhannath is the one ("male") who carries in his movements, in his appearance and in his language the characteristics of a woman. There are two types; the first is the one in whom these characteristics are innate, he did not put them on by himself, and therein is no guilt, no blame and no shame, as long as he does not perform any (illicit) act or exploit it for money (prostitution etc.). The second type acts like a woman out of immoral purposes and he is the sinner and blameworthy.[107]

While Iran has outlawed homosexuality, Iranian Shi'a thinkers such as Ayatollah Khomeini have allowed for transgender people to change their sex so that they can enter heterosexual relationships. This position has been confirmed by the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and is also supported by many other Iranian clerics.

Iran carries out more sex change operations than any other nation in the world except for Thailand. It is regarded as a cure for homosexuality, which is punishable by death under Iranian law. The government even provides up to half the cost for those needing financial assistance and a sex change is recognized on the birth certificate.[108]

See also

- StraightWay Foundation

- Islamic religious police

- LGBT in the Middle East

- LGBT rights at the United Nations

- Transsexuality in Iran

Rights activists

- Afdhere Jama, editor of Huriyah

- Arsham Parsi, Iranian LGBT activist

- El-Farouk Khaki, founder of Salaam, the first homosexual Muslim group in Canada

- Faisal Alam, Pakistani American founder of Al-Fatiha Foundation

- Irshad Manji, Canadian lesbian and human rights activist

- Mahmoud Asgari and Ayaz Marhoni

- Maryam Hatoon Molkara, campaigner for transsexual rights in Iran

- Waheed Alli, Baron Alli, British gay politician

Other

- A Jihad for Love, documentary about devout gay Muslims

- Bacchá

- Festival of Muslim Cultures

- Gay Muslims, documentary

- Ghilman

- Inclusive Mosque Initiative

- Köçek

- Malik Ayaz

- Nazar ila'l-murd

References

- ^ "The Qu'ran and Homosexuality". Internet History Sourcebooks Project. Fordham University. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

Richard Burton suggests the following Qu'ranic verses as relevant to homosexuality:

- ^ a b c d e f Ali, Kecia (2006). Sexual Ethics & Islam. Oxford, England: OneWorld Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-85168-456-4.

- ^ [1] Archived 2010-06-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Khaled El-Rouayheb. Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World 1500–1800. pp. 12 ff.

- ^ "Lesbian and Gay Rights in the World" (PDF). ILGA. May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Abu Dawud 32:4087

- ^ Sahih Bukhari 7:72:774

- ^ Ibn Majah Vol. 3, Book 9, Hadith 1903

- ^ "UK party leaders back global gay rights campaign". BBC Online. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

At present, homosexuality is illegal in 76 countries, including 38 within the Commonwealth. At least five countries - the Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mauritania and Sudan - have used the death penalty against gay people.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

Facts as drug trafficking, homosexual behaviour, and apostasy are liable to capital punishment.

- ^ a b "Man Accused of "Gay Handshake" Stands Trial in Dubai". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Anderson, Ben (2007). "The Politics of Homosexuality in Africa" (PDF). Africana. 1 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ottosson, Daniel (2013). "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults" (PDF). International Lesbian and Gay Association (ILGA). p. Page 7. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ Ready, Freda. The Cornell Daily Sun article [2] Retrieved on December 4, 2002

- ^ "Syria: Treatment and human rights situation of homosexuals" (PDF). Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ a b "In response to anti-LGBT fatwa, Jokowi urged to abolish laws targeting minorities". The Jakarta Post. 18 March 2015. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Indonesia: Situation of sexual minorities, including legislation, treatment by society and authorities, state protection and support services available (2013- June 2015)". Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. 8 July 2015. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ a b Lowen, Mark (2009-07-30). "Albania 'to approve gay marriage'". BBC News. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ a b Rough Guide to South East Asia: Third Edition. Rough Guides Ltd. August 2005. p. 74. ISBN 1-84353-437-1.

- ^ Lucas Paoli Itaborahy; Jingshu Zhu (May 2014). "State-sponsored Homophobia - A world survey of laws: Criminalisation, protection and recognition of same-sex love" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ "Kuwait Law". ILGA Asia. 2009. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan On Enactment of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan". Legislationline.org. Retrieved 2016-03-22.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle; Von Ahn, Lisa (17 May 2016). "Muslim states block gay groups from U.N. AIDS meeting; U.S. protests". Reuters. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Evans, Robert (8 March 2012). "Islamic states, Africans walk out on UN gay panel". Reuters. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ Solash, Richard (7 March 2012). "Historic UN Session On Gay Rights Marked By Arab Walkout". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- ^ South Africa leads United Nations on gay rights | News | National | Mail & Guardian. Mg.co.za (2012-03-09). Retrieved on 2013-09-27.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on November 23, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Over 80 Nations Support Statement at Human Rights Council on LGBT Rights » US Mission Geneva". Geneva.usmission.gov. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ (references 7:80–84, 11:77–83, 21:74, 22:43, 26:165–175, 27:56–59, and 29:27–33)

- ^ Duran (1993) p. 179

- ^ Kligerman (2007) pp. 53–54

- ^ a b c Wayne Dynes, Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality, New York, 1990.

- ^ Wafer, Jim (1997). "Muhammad and Male Homosexuality". In Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (ed.). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History and Literature. New York University Press. p. 88. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ "Bookmarkable URL intermediate page". web.b.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Wafer, Jim (1997). "Muhammad and Male Homosexuality". In Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (ed.). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History and Literature. New York University Press. pp. 89–90. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ a b c d e f Ed. C. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Leiden, 1983

- ^ Wafer, Jim (1997). "Muhammad and Male Homosexuality". In Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (ed.). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History and Literature. New York University Press. p. 89. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ Should beheading be the penalty for homosexuals?

- ^ Duran, K. (1993). Homosexuality in Islam, p. 184. Cited in: Kligerman (2007) p. 54.

- ^ "Threats to Behead Homosexuals: Shari`ah or Politics? - Disciplinary Penalties (ta`zir) - counsels". OnIslam.net. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ^ "Why Gay Marriage May Not Be Contrary To Islam". Huffingtonpost.ca. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ "The Homosexual Challenge to Muslim Ethics". Lamppostproductions.com. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ "On Same-Sex Marriage". Islawmix.org. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ A Muslim's Thoughts about the Sexual Question, (1984)

- ^ Massad, Joseph Andoni (2007). Desiring Arabs. University of Chicago Press. pp. 203–4.

- ^ Kugle, Scott (2010). Homosexuality in Islam. Oxford, England: Oneworld Publications. pp. 42–49.

- ^ The Hudud: The Hudud are the Seven Specific Crimes in Islamic Criminal Law and Their Mandatory Punishments, 1995 Muhammad Sidahmad

- ^ Stonebanks, Christopher Darius (2010). Teaching Against Islamophobia. p. 190.

- ^ Tax, Meredith (2010). Double Bind. p. 46.

- ^ Editors, The. "Abu Nuwas | Persian poet". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Neill 2008, p. 308.

- ^ Ritter 2003, p. 309-310.

- ^ Kinross, The Ottoman Centuries, pp. 115–16.

- ^ History of the Ottoman Empire, Mohamed Farid Bey

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World, MacMillan Reference USA, 2004, p.316

- ^ Welch A., "Wordly and Otherwordly Love in Safavi Painting", Persian Painting from the Mongols to the Qajars, Éditions R. Hillenbrand, Londres, 2000, p. 303 et p. 309.

- ^ Tehmina Kazi (7 Oct 2011). "The Ottoman empire's secular history undermines sharia claims". UK Guardian.

- ^ Ishtiaq Hussain (15 Feb 2011). "The Tanzimat: Secular Reforms in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). Faith Matters.

- ^ Schmitt&Sofer, p.36

- ^ Schmitt&Sofer, pp.x-xi

- ^ Habib, p.287

- ^ Arno Schmitt, Jehoeda Sofer, "Sexuality and Eroticism among Males in Muslim Societies" (The Haworth Press, 1992) p.8. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ Dialmy, pp.32 and 35, footnote 34

- ^ Schmitt&Sofer, p.7

- ^ Murray&Roscoe, passim

- ^ Qobil, Rustam. "The sexually abused dancing boys of Afghanistan - BBC News". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ "7 countries still put people to death for same-sex acts". ILGA. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ "Homosexuality and Islam". ReligionFacts. 2005-07-19. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ "United Arab Emirates". Retrieved 27 October 2015.

Facts as drug trafficking, homosexual behaviour, and apostasy are liable to capital punishment.

- ^ Fifa boss Sepp Blatter sorry for Qatar 'gay' remarks, BBC

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michelangelo-signorile/saudi-arabia-beheads-gays_b_6354636.html |title=Saudi Arabia Beheads Gays|

- ^ ISIL targets gays in Brutal public killings

- ^ "Login". timesonline.co.uk.

- ^ After Deoband, other Muslim leaders condemn homosexuality, Times of India

- ^ Tehmina Kazi. "The Ottoman empire's secular history undermines sharia claims". the Guardian.

- ^ "ILGA-Europe". ilga-europe.org.

- ^ ISIL targets gays in Brutal public killings

- ^ "Al Arabiya: "Moroccan "bride" detained for gay wedding"". alarabiya.net.

- ^ "Al Arabiya: "Morocco sentences gay 'bride' to jail"". alarabiya.net.

- ^ "FRANCE - Concilier islam et homosexualité, le combat de Ludovic-Mohamed Zahed - France 24". France 24.

- ^ Gay-friendly 'mosque' opens in Paris retrieved 12 February 2013

- ^ "Homosexual Muslims - HM2F". homosexuels-musulmans.org.

- ^ Bradlee Dean: Keith Ellison is advancing Sharia law through ‘homosexual agenda’ retrieved 15 January 2013

- ^ Keith Ellison: Minnesota Anti-Gay Marriage Amendment Will Fail retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ Tadros, Sherine (6 November 2014). "Crackdown As Men Jailed Over 'Gay Wedding'". Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ SeattleTimes - Arson attack

- ^ Gay refugees facing abuse in asylum shelters

- ^ Hunter, Matt; Stanton, Jenny; Lambiet, Jose (June 12, 2016). "Worst Mass Shooter in U.S. History". The Daily Mail. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ Tsukayama, Hayley; Goldman, Adam; Holley, Peter; Berman, Mark (12 June 2016). "Orlando nightclub shooting: 50 killed in shooting rampage at gay club; gunman pledged allegiance to ISIS". The Washington Post. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Jordans, Frank (June 17, 2011). "U.N. Gay Rights Protection Resolution Passes, Hailed As 'Historic Moment'". Associated Press.

- ^ "UN issues first report on human rights of gay and lesbian people". United Nations. 15 December 2011.

- ^ Pew Research Center: The Global Divide on Homosexuality retrieved 9 June 2013

- ^ http://dvmx.com/British_Muslim_Youth.pdf

- ^ Butt, Riazat (2009-05-07). "Muslims in Britain have zero tolerance of homosexuality, says poll". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Bundesministerium des Inneren: Zusammenfassung "Muslimisches Leben in Deutschland", p. 2

- ^ Liljeberg Research International: Deutsch-Türkische Lebens- und Wertewelten 2012, July/August 2012, p. 73

- ^ "Cyber Mecca", The Advocate, March 14, 2000

- ^ "Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity". Muslimalliance.org. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ^ Tim Herbert, "Queer chronicles", Weekend Australian, October 7, 2006, Qld Review Edition.

- ^ "Home". Imaan.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ Throckmorton, Warren; Pattison, M. L. (June 2002). "Initial empirical and clinical findings concerning the change process for ex-gays". Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 33 (3). American Psychological Association: 242–248. doi:10.1037/0735-7028.33.3.242.

- ^ "Just the Facts about Sexual Orientation & Youth". American Psychological Association. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ^ "Bachmann Silent on Allegations Her Clinic Offers Gay Conversion Therapy". ABC News. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ "Therapeutic Responses to Sexual Orientation" (PDF). American Psychological Association.

- ^ Banerji, Robin (30 November 2012). "Gay-friendly 'mosque' opens in Paris". BBC News.

- ^ Power, Shannon (3 May 2016). "Being gay and muslim: 'death is your repentance'". Star Observer. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Rowson, Everett K. (October 1991). "The Effeminates of Early Medina" (PDF). Journal of the American Oriental Society. 111 (4). American Oriental Society: 671–693. doi:10.2307/603399. JSTOR 603399.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Barford, Vanessa (2008-02-25). "Iran's 'diagnosed transsexuals'". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

Bibliography

- Dialmy, Abdessamad (2010). Which Sex Education for Young Muslims?. World Congress of Muslim Philanthropists.

- Habib, Samar (1997). Islam and Homosexuality, vol.2. ABC-CLIO.

- Jahangir, Junaid bin (2010). "Implied Cases for Muslim Same-Sex Unions". In Samar Habib (ed.). Islam and homosexuality, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO.

- Template:De icon Georg Klauda: Die Vertreibung aus dem Serail. Europa und die Heteronormierung der islamischen Welt. Männerschwarm Verlag, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-939542-34-6. See pages at Google Books.

- Schmitt, Arno; Sofer, Jehoeda (1992). Sexuality and Eroticism among Males in Muslim Societies. Haworth Press.

- Schmitt, Arno (2001–2002). Liwat im Fiqh: Männliche Homosexualität?. Vol. IV. Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies.

- Van Jivraj, Suhraiya; de Jong, Anisa (2001). Muslim Moral Instruction on Homosexuality. Yoesuf Foundation Conference on Islam in the West and Homosexuality – Strategies for Action.

- Wafer, Jim (1997). "Mohammad and Male Homosexuality". In Stephen O. Murray & Will Roscoe (ed.). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History and Literature. New York University Press.

- Duran, Khalid. Homosexuality in Islam, in: Swidler, Anne (ed.) "Homosexuality and World Religions" (1993). Trinity Press International, Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. ISBN 1-56338-051-X

- Kilgerman, Nicole (2007). Homosexuality in Islam: A Difficult Paradox. Macalester Islam Journal 2(3):52-64, Berkeley Electronic press.

- Khaled El-Rouayheb, Before Homosexuality in the Arab–Islamic World, 1500–1800 Chicago, 2009. ISBN 978-0-226-72989-3.

- Luongo, Michael (ed.), Gay Travels in the Muslim World Haworth Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1-56023-340-4.

- Everett K. Rowson, J.W. Wright (eds.), Homoeroticism in Classical Arabic Literature New York, 1997

- Arno Schmitt and Jehoeda Sofer (eds.), Sexuality and Eroticism Among Males in Moslem Societies Harrington Park Press 1992

- Arno Schmitt and Gianni de Martino, Kleine Schriften zu zwischenmännlicher Sexualität und Erotik in der muslimischen Gesellschaft, Berlin, Gustav-Müller-Str. 10 : A. Schmitt, 1985

- Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (eds.), "Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature" NYU Press New York 1997

- Wafer, Jim (1997) "Muhammad and Male Homosexuality" in "Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature" by Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (eds.), NYU Press New York

- Wafer, Jim (1997) "The Symbolism of Male Love in Islamic Mysthical Literature" in "Islamic Homosexualities: culture, history, and literature" by Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (eds.), NYU Press New York 1997

- Vincenzo Patanè, "Homosexuality in the Middle East and North Africa" in: Aldrich, Robert (ed.) Gay Life and Culture: A World History, Thames & Hudson, London, 2006

- [Pellat, Charles.] "Liwat". Encyclopedia of Islam. New edition. Vol. 5. Leiden: Brill, 1986. pp. 776–79.

External links

- Islam and homosexuality: Straight but narrow, The Economist, Feb 4th 2012

- Homosexuality: What is the real sickness? Illustrative Article from AbdurRahman.org

- Gay Rights: Who are the Real Enemies of Liberation?, Socialist Review

- Imaan supports LGBT Muslim people, their families and friends (UK)

- The StraightWay Foundation (UK)

- Intolerant cruelty This special edition of Diabolic Digest explores the question of homosexuality in the Middle East.

- Islamic law: (much) Theory and (just enough) Practice

- Safra Project — Sexuality, Gender and Islam

- Queer Sexuality and Identity in the Qur'an and Hadith, interpretation of Islamic texts in historical context

- Sodomy in Islamic Jurisprudence (article in German; engl. Summary)

- Sexuality and Eroticism Among Males in Moslem Societies by Arno Schmitt and Jehoeda Sofer (eds.), Harrington Park Press 1992

- Islam and Homosexuality

- Gay Travels in the Muslim World, an anthology of travel essays by gay Muslim and non-Muslim men; Luongo, Michael (ed.) Haworth Press

- Islam and Homosexuality

- Kotb, H.G.: Sexuality in Islam at the Magnus Hirschfeld Archive for Sexology

- Homosexuality in Urdu poetry: Tolerance in medieval India and early Islamic societies

- lgbti.org Turkey LGBTI Union