Venus

| File:Venus-pioneer-uv.jpg

Ultraviolet image of Venus' clouds as seen by | |||||||

| Orbital characteristics (Epoch J2000) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | 108,208,926 km 0.723 331 99 AU | ||||||

| Orbital circumference | 0.680 Tm 4.545 AU | ||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.006 773 23 | ||||||

| Perihelion | 107,476,002 km 0.718 432 70 AU | ||||||

| Aphelion | 108,941,849 km 0.728 231 28 AU | ||||||

| Orbital period | 224.700 96 d (0.615 197 7 a) | ||||||

| Synodic period | 583.92 d | ||||||

| Avg. Orbital Speed | 35.020 km/s | ||||||

| Max. Orbital Speed | 35.259 km/s | ||||||

| Min. Orbital Speed | 34.784 km/s | ||||||

| Inclination | 3.394 71° (3.86° to Sun's equator) | ||||||

| Longitude of the ascending node |

76.680 69° | ||||||

| Argument of the perihelion |

54.852 29° | ||||||

| Number of satellites | 0 | ||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||

| Equatorial diameter | 12,103.7 km (0.949 Earths) | ||||||

| Surface area | 4.60×108 km2 (0.902 Earths) | ||||||

| Volume | 9.28×1011 km³ (0.857 Earths) | ||||||

| Mass | 4.8685×1024 kg (0.815 Earths) | ||||||

| Mean density | 5.204 g/cm3 | ||||||

| Equatorial gravity | 8.87 m/s2 (0.904 gee) | ||||||

| Escape velocity | 10.36 km/s | ||||||

| Rotation period | -243.0185 d | ||||||

| Rotation velocity | 6.52 km/h (at the equator) | ||||||

| Axial tilt | 2.64° | ||||||

| Right ascension of North pole |

272.76° (18 h 11 min 2 s) 1 | ||||||

| Declination | 67.16° | ||||||

| Albedo | 0.65 | ||||||

| Surface* temp. |

| ||||||

| (*min temperature refers to cloud tops only) | |||||||

| Atmospheric characteristics | |||||||

| Atmospheric pressure | 9321.9 kPa | ||||||

| Carbon dioxide | 96% | ||||||

| Nitrogen | 3% | ||||||

| Sulfur dioxide Water vapor |

trace | ||||||

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, named after the Roman goddess Venus. It is a terrestrial planet, very similar in size and bulk composition to Earth; it is sometimes called Earth's "sister planet" as a result of this similarity. Although all planets' orbits are elliptical, Venus' orbit is the most nearly circular of all, with the Sun located only 0.7% from the true center of Venus' orbit.

Because Venus is closer to the Sun than Earth is, it is always in roughly the same direction as the Sun (the greatest elongation is 47.8°), so on Earth it can only be seen just before sunrise or just after sunset. It is sometimes referred to as the "Morning Star" or the "Evening Star", and when it appears it is by far the brightest point of light in the sky.

Venus was known to ancient Babylonians around 1600 BC, and probably was known long before in prehistoric times due to its high visibility. Its symbol is a stylized representation of the goddess Venus' hand mirror: a circle with a small cross underneath (Unicode: ♀).

Physical characteristics

Atmosphere

Venus has an atmosphere consisting mainly of carbon dioxide and a small amount of nitrogen, with a pressure at the surface about 90 times that of Earth (a pressure equivalent to a depth of 1 kilometre under Earth's ocean). This enormous CO2-rich atmosphere results in a strong greenhouse effect that raises the surface temperature approximately 400°C above what it would be otherwise, causing temperatures at the surface to reach 500°C. This makes Venus' surface hotter than Mercury's, despite being nearly twice as distant from the Sun and only receiving 25% the solar irradiance (2613.9 W/m² in the upper atmosphere, and just 1071.1 W/m² at the surface). Due to the thermal inertia and convection of its dense atmosphere, the temperature does not vary significantly between the night and day sides of Venus despite its extremely slow rotation (less than one rotation per Venusian year; at the equator, Venus' surface rotates at a mere 6.5 km/h). Winds in the upper atmosphere circle the planet in only 4 days, helping to distribute the heat.

There are strong 350-kilometre-per-hour winds at the cloud tops, but winds at the surface are very slow, no more than a few kilometres per hour. However, due to the high density of the atmosphere at Venus' surface, even such slow winds exert a significant amount of force against obstructions. The clouds are mainly composed of sulfur dioxide and sulphuric acid droplets and cover the planet completely, obscuring any surface details to the human eye. The temperature at the tops of these clouds is approximately −45°C. The official mean surface temperature of Venus, as given by NASA, is 464°C. The minimal value of the temperature, listed in the table, refers to cloud tops —on surface the temperature is never below 400°C.

Surface features

Venus has slow retrograde rotation, meaning it rotates from east to west instead of west to east as most of the other major planets. (Pluto and Uranus also have retrograde rotation, though Uranus' axis, tilted at 97.86 degrees, almost lies in its orbital plane.) It is not known why Venus is different in this manner, although it may be the result of a collision with a very large asteroid at some time in the distant past. In addition to this unusual retrograde rotation, the periods of Venus' rotation and of its orbit are synchronized in such a way that it always presents the same face toward Earth when the two planets are at their closest approach (5.001 Venusian days between each inferior conjunction). This may be the result of tidal locking, with tidal forces affecting Venus' rotation whenever the planets get close enough together, or it may simply be a coincidence.

Venus has two major continent-like highlands on its surface, rising over vast plains. The northern highland is named Ishtar Terra and has Venus' highest mountains, named the Maxwell Montes (roughly 2 km taller than Mount Everest) after James Clerk Maxwell, which surround the plateau Lakshmi Planum. Ishtar Terra is about the size of Australia. In the southern hemisphere is the larger Aphrodite Terra, about the size of South America. Between these highlands are a number of broad depressions, including Atalanta Planitia, Guinevere Planitia, and Lavinia Planitia. With only the exception of Maxwell Montes, all surface features on Venus are named after real or mythological females. Due to Venus' thick atmosphere, which causes meteors to decelerate as they fall toward the surface, no impact crater smaller than about 3.2 km in diameter can form.

Nearly 90% of Venus' surface appears to consist of recently-solidified basalt lava, with very few meteor craters. This suggests that Venus underwent a major resurfacing event recently. The interior of Venus is probably similar to that of Earth: an iron core about 3000 km in radius, with a molten rocky mantle making up the majority of the planet. Recent results from the Magellan gravity data indicate that Venus' crust is stronger and thicker than had previously been assumed. It is theorized that Venus does not have mobile plate tectonics like Earth does, but instead undergoes massive volcanic upwellings at regular intervals that inundate its surface with fresh lava; the oldest features present on Venus seem to be only around 800 million years old, with most of the terrain being considerably younger (though still not less than several hundred million years for the most part). Recent findings suggest that Venus is still volcanically active in isolated geological hot spots.

Venus' intrinsic magnetic field has been found very weak compared to other planets in the solar system. This may be due to its slow rotation being insufficient to drive an internal dynamo of liquid iron. As a result, solar wind strikes Venus' upper atmosphere without mediation. It is thought that Venus originally had as much water as Earth, but that under the Sun's assault water vapor in the upper atmosphere was split into hydrogen and oxygen, with the hydrogen escaping into space due to its low molecular mass; the ratio of hydrogen to deuterium (a heavier isotope of hydrogen which doesn't escape as quickly) in Venus' atmosphere seems to support this theory. The oxygen is thought to have combined with atoms in the crust and disappeared from the atmosphere. Because of their dryness, Venus' rocks are much harder than Earth's, which leads to steeper mountains, cliffs and other features.

Venus was once thought to possess a moon, named Neith after the mysterious goddess of Sais (whose veil no mortal raised), first observed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1672. Sporadic sightings of Neith by astronomers continued until 1892, but these sightings have since been discredited (they were mostly faint stars that happened to be in the right place at the right time) and Venus is now known to be moonless.

Observations and Explorations of Venus

Historical observations

Venus is the most prominent astronomical feature in the morning and evening sky on Earth (besides the Sun and Moon), and has been known of since before recorded history. One of the oldest surviving astronomical documents, from the Babylonian library of Ashurbanipal around 1600 BC, is a 21-year record of the appearances of Venus (which the early Babylonians called Nindaranna). The ancient Sumerians and Babylonians called Venus Dil-bat or Dil-i-pat; in Akkadia it was the special star of the mother-god Ishtar; and in Chinese it is the god Jin xing. Venus was the most important celestial body observed by the Maya, who called it Chak ek, "the Great Star", and considered it a representation of Quetzalcoatl; they apparently did not worship any of the other planets. (See also Maya calendar.)

Early Greeks thought that the evening and morning appearances of Venus represented two different objects, calling it Hesperus when it appeared in the western evening sky and Phosphorus when it appeared in the eastern morning sky. They eventually came to recognize that both objects were the same planet; Pythagoras is given credit for this realization. In the 4th century BC, Heraclides Ponticus proposed that both Venus and Mercury orbited the Sun rather than Earth. The name Venus comes from the Roman goddess of love and beauty.

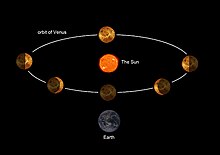

Because its orbit takes it between the Earth and the Sun, Venus as seen from Earth exhibits visible phases in much the same manner as the Earth's Moon. Galileo Galilei was the first person to observe the phases of Venus in December 1610, an observation which supported Copernicus' then contentious heliocentric description of the solar system. He also noted changes in the size of Venus' visible diameter when it was in different phases, suggesting that it was farther from Earth when it was full and nearer when it was a crescent. This observation strongly supported the heliocentric model.

Transits of Venus, when the planet crosses directly between the Earth and the Sun' visible disc, are rare astronomical events. The first time such a transit was observed was on December 4, 1639 by Jeremiah Horrocks and William Crabtree. A transit in 1761 observed by Mikhail Lomonosov provided the first evidence that Venus had an atmosphere, and the 19th century observations of parallax during its transits allowed the distance between the Earth and Sun to be accurately calculated for the first time. The previous set of transits of Venus occurred within the interval of 1874–1882, and the next set of transits will occur in the period of 2004–2012.

In the 19th century, many observers stated that Venus had a period of rotation of roughly 24 hours. Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli was the first to predict a significantly slower rotation, proposing that Venus was tidally locked with the Sun (as he had also proposed for Mercury). While not actually true for either body, this was still a reasonably accurate estimate. The near-resonance between its rotation and its closest approach to Earth helped to create this impression, as Venus always seemed to be facing the same direction when it was in the best location for observations to be made. The rotation rate of Venus was first measured during the 1961 conjunction, observed by radar from a 26-meter antenna at Goldstone California, the Jodrell Bank Radio Observatory in the UK, and the Soviet deep space facility in Evpatoriia. Accuracy was refined at each subsequent conjunction, primarily from measurments made from Goldstone and Evpatoriia. The fact that rotation was retrograde was not confirmed until 1964.

Before radio observations in the 1960s, many believed that Venus contained a lush, earth-like environment. This was due to the planet's size and orbital radius, which suggested a fairly earth-like situation as well as to the thick layer of clouds which prevented the surface from being seen. Among the speculations on Venus were that it had a jungle like environment or that it had oceans of either petroleum or carbonated water. However, microwave observations in 1956, by C. Mayer et al, indicated a high-temperature source (600 K). Strangely, millimeter-band observations made by A.D. Kuzmin indicated much lower temperatures. Two competing theories explained the unusual radio spectrum, one suggesting the high temperatures originated in the ionosphere, and another suggesting a hot planetary surface.

Observation by spacecraft

There have been numerous unmanned missions to Venus. Several have included a soft landing on the surface, with up to 110 minutes of communication from the surface, all without return.

Getting to Venus

Venus orbits closer to the Sun than Earth does, with an orbital distance only 72% that of the Earth. Because of this, a spacecraft must travel over 41 million kilometers down into the Sun's gravitational potential well, resulting in a large decrease in the spacecraft's potential energy. The liberated potential energy is mostly turned into kinetic energy, increasing the velocity of the spacecraft, so the speed and direction of the spacecraft must be altered quite radically to permit a close approach to Venus. One can imagine driving along a road next to a high, steep cliff with another road at the bottom; the journey from Earth to Venus is rather like swerving off the cliff, freefalling for some time, and then trying to land safely and merge with traffic on the lower road.

Early flybys

On February 12, 1961, Venera 1 was the first probe launched to another planet. An overheated orientation sensor caused it to malfunction, but Venera-1 was first to combine all the necessary features of an interplanetary spacecraft: solar panels, parabolic telemetry antenna, 3-axis stabilization, course-correction engine, and the first launch from parking orbit.

The first successful Venus probe was the American Mariner 2 spacecraft, which flew past Venus in 1962. A modified Ranger Moon probe, it established that Venus has no magnetic field and measured the planet's thermal microwave emissions.

The Soviet Union launched the Zond 1 probe to Venus on April 2, 1964, but it malfunctioned sometime after its May 16 telemetry session.

Early landings

On March 1, 1966 the Venera 3 Soviet space probe crash-landed on Venus, becoming the first spacecraft to reach the planet's surface. Its sister craft Venera 2 failed from overheating shortly before completing its flyby mission.

The descent capsule of Venera 4 entered the atmosphere of Venus on October 18, 1967. The first probe to return direct measurements from another planet, the capsule measured temperature, pressure, density and performed 11 automatic chemical experiments to analyze the atmosphere. It showed 95% carbon dioxide, and in combination with radio occultation data from the Mariner 5 probe, it showed that surface pressures were far greater than expected (75 - 100 atmospheres).

These results were verified and refined by the Venera 5 and Venera 6 missions in May 16 and 17 of 1969. But thus far, none of these missions had reached the surface. Venera-4's battery ran out while still slowly floating through the massive atmosphere, and Venera-5 and 6 were crushed by high pressure 18 km above the surface.

The first successful landing on Venus was by Venera 7 on December 15, 1970. It relayed surface temperatures of 457 to 474°C. Venera 8 landed on July 22, 1972. In addition to pressure and temperature profiles, a photometer showed that the clouds of Venus formed a layer, ending over 35 km above the surface. A gamma ray spectrometer analyzed the chemical composition of the crust.

Early orbiters

The Soviet probe Venera 9 entered orbit on October 22, 1975, becoming the first artificial satellte of Venus. A battery of cameras and spectrometers returned information about the planet's clouds, ionosphere and magnetosphere, as well as performing bistatic radar measurements of the surface.

The 660 kg descent vehicle separated from Venera 9 and landed, taking the first pictures of the surface and analyzing the crust with a gamma-ray spectrometer and a densitometer. During descent, pressure, temperature and photometric measurements were made, as well as backscattering and multi-angle scattering (nephelometer) measurements of cloud density. It was discovered that the clouds of Venus are formed in three distinct layers. On October 25, Venera 10 arrived and carried out a similar program of study.

Pioneer Venus

In 1978 NASA sent two Pioneer spacecraft to Venus. The Pioneer mission consisted of two components, launched separately: an Orbiter and a Multiprobe. The Pioneer Venus Multiprobe carried one large and three small atmospheric probes. The large probe was released on November 16, 1978 and the three small probes on November 20. All four probes entered the Venus atmosphere on December 9, followed by the delivery vehicle. Although not expected to survive the descent through the atmosphere, one probe continued to operate for 45 minutes after reaching the surface. The Pioneer Venus Orbiter was inserted into an elliptical orbit around Venus on December 4, 1978. It carried 17 experiments and operated until the fuel used to maintain its orbital position was exhausted and atmospheric entry destroyed the spacecraft in August 1992.

Russian successes

Also in 1978, Venera 11 and Venera 12 flew past Venus, dropping descent vehicles on December 21 and December 25 respectively. The landers carried color cameras and a soil drill and analyzer, which unfortunately malfunctioned. Each lander made measurements with a nephelometer, mass spectrometer, gas chromatograph, and a cloud-droplet chemcial analyzer using x-ray fluorescence that unexpectedly discovered a large proportion of chlorine in the clouds, in addition to sulfur. Strong lightning activity was also detected.

Venera 13 and Venera 14 carried out essentially the same mission, arriving at Venus on March 1 and March 5, 1982. This time, color camera and soil-drilling/analysis experiments were successful. x-ray fluorescence analysis of soil samples showed results similar to posassium-rich basalt rock.

On October 10 and October 11, 1983, Venera 15 and Venera 16 entered polar orbits around Venus. Venera 15 analyzed and mapped the upper atmosphere with an infrared Fourier spectrometer. From November 11 to July 10, both satellites mapped the northern third of the planet with synthetic aperture radar. These results provided the first detailed understanding of the surface geology of Venus, including the discovery of unusual massive shield volcanos such as coronae and arachnoids. Venus had no evidence of plate tectonics, unless the northern third of the planet happened to be a single plate.

The Soviet Vega 1 and Vega 2 probes encountered Venus on June 11 and June 15 of 1985. Landing vehicles carried experiments focusing on cloud aerosol composition and structure. Each carried an ultraviolet absorption spectromer, aerosol particle-size analyzers, and devices for collecting aerosol material and analyzing it with a mass spectrometer, a gas chromatograph, and an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The upper two layers of the clouds were found to be sufuric acid droplets, but the lower layer is probably composed of phosphoric acid solution. The crust of Venus was analyzed with the soil drill experiment and a gamma-ray spectrometer.

The Vega missions also deployed balloon-born aerostat probes that floated at about 53 km altitude for 46 hours, traveling about 1/3 of the way around the planet. These measured wind speed, temperature, pressure and cloud density. More turbulence and convection activity than expected was discovered, including occasional plunges of 1 to 3 kilometers in downdrafts. The Vega spacecrafts continued on to rendezvous with Halley's Comet nine months later, bringing an additional 14 instruments and cameras for that mission.

Magellan

On August 10, 1990, the US Magellan probe arrived at its orbit around the planet and started a mission of detailed radar mapping. 98% of the surface was mapped with a resolution of approximately 100m. After a four year mission, Magellan, as planned, plunged into the atmosphere on October 11, 1994, and partly vaporized; some sections are thought to have hit the planet's surface.

Recent flybys

Several space probes en route to other destinations have used flybys of Venus to increase their speed via the gravitational slingshot method. These include the Galileo mission to Jupiter and the Cassini-Huygens Mission to Saturn (two flybys).

Future missions

Venus Express is a future mission proposed by the European Space Agency which would study Venus from orbit. Future flybys en route to other destinations include the MESSENGER mission to Mercury.

Venus in fiction

- Until it was penetrated by probes, Venus' opaque cloud layer gave science fiction writers free rein in imagining the planet's surface, and they frequently imagined it to be Earth-like. Venus was the home planet of the Mekon, arch-enemy of the 1950s comic book hero Dan Dare, and was the site of a second garden of Eden in C. S. Lewis' novel Perelandra. In Olaf Stapledon's epic Last and First Men, Venus is an oceanic idyll where humans evolve the power of flight.

- A more scientifically accurate depiction of the planet is offered in Ben Bova's novel Venus (2000), although its literary merits are debatable.

- A presumably terraformed Venus was the setting of one episode of the anime Cowboy Bebop. In the show Venus was revealed to be an arid but habitable world. Much of the population lived in floating cities in the sky.

- Venus is also the location of several Starfleet Academy training facilities and terraforming stations in the fictional Star Trek universe, and it is briefly mentioned in Arthur C. Clarke's 3001: The Final Odyssey.

See also

References

- NASA's Venus fact sheet

- http://www.nineplanets.org/venus.html

- The Soviet Exploration of Venus

- Analysis of the colour of Venus' skies, based on Venera data

- Venus Express homepage

[[pt:V%E9nus]]