O Canada

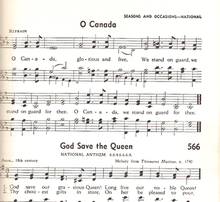

Sheet music for Canada's national anthem, in English, French, and Inuktitut | |

National anthem of Canada | |

| Also known as | Template:Lang-fr |

|---|---|

| Lyrics | Adolphe-Basile Routhier (French, 1880), Robert Stanley Weir (English, 1908) |

| Music | Calixa Lavallée, 1880 |

| Adopted | July 1, 1980 |

| Audio sample | |

O Canada | |

"O Canada" (Template:Lang-fr) is the national anthem of Canada. The song was originally commissioned by Lieutenant Governor of Quebec Théodore Robitaille for the 1880 Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day ceremony; Calixa Lavallée composed the music, after which, words were written by the poet and judge Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier. The lyrics were originally in French; an English version was created in 1906.[1] Robert Stanley Weir wrote in 1908 another English version, which is the official and most popular version, one that is not a literal translation of the French. Weir's lyrics have been revised twice, taking their present form in 1980, but the French lyrics remain unaltered. "O Canada" had served as a de facto national anthem since 1939, officially becoming Canada's national anthem in 1980 when the Act of Parliament making it so received royal assent and became effective on July 1 as part of that year's Dominion Day (now known as Canada Day) celebrations.[1][2]

Official lyrics

The Queen-in-Council established set lyrics for "O Canada" in Canada's two official languages, English and French. The lyrics are as follows:[1][3][4]

| Official English | Official French | Translation by the Parliamentary translation bureau |

|

O Canada! |

Ô Canada! |

O Canada! |

Unofficial bilingual version[5]

O Canada!

Our home and native land!

True patriot love in all thy sons command.

Car ton bras sait porter l'épée,

Il sait porter la croix!

Ton histoire est une épopée

Des plus brillants exploits.

God keep our land glorious and free!

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

It has been noted that the opening theme of "O Canada" bears a strong resemblance to the "March of the Priests" from the opera The Magic Flute, composed in 1791 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.[6] The line "The True North strong and free" is based on the Lord Tennyson's description of Canada as "that true North, whereof we lately heard / A strain to shame us". In the context of Tennyson's poem To the Queen, the word true means "loyal" or "faithful".[6]

The lyrics and melody of "O Canada" are both in the public domain,[1] a status unaffected by the trademarking of the phrases "with glowing hearts" and "[des plus brillants exploits] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)" for the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.[7] Two provinces have adopted Latin translations of phrases from the English lyrics as their mottos: Manitoba—[Gloriosus et Liber] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Glorious and Free)[8]—and Alberta—[Fortis et Liber] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Strong and Free).[9] Similarly, the Canadian Army's motto is [Vigilamus pro te] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (we stand on guard for thee).

Lyric changes

Weir's original lyrics from 1908 contained no religious references and used the phrase "thou dost in us command" before they were changed by Weir in 1914 to read "in all thy sons command".[1][10][11][12] In 1926, a fourth verse of a religious nature was added.[13]

In June 1990, Toronto City Council voted 12 to 7 in favour of recommending to the Canadian government that the phrase "our home and native land" be changed to "our home and cherished land" and that "in all thy sons command" be partly reverted to "in all of us command". Councillor Howard Moscoe said that the words "native land" were not appropriate for the many Canadians who were not native-born and that the word "sons" implied "that women can't feel true patriotism or love for Canada."[14] Senator Vivienne Poy similarly criticized the English lyrics of the anthem as being sexist and she introduced a bill in 2002 proposing to change the phrase "in all thy sons command" to "in all of us command."[13] In the late 2000s, the anthem's religious references (to God in English and to the Christian cross in French) were criticized by secularists.[15][16]

In the speech from the throne delivered by Governor General Michaëlle Jean on March 3, 2010, a plan to have parliament review the "original gender-neutral wording of the national anthem" was announced.[17] However, three-quarters of Canadians polled after the speech objected to the proposal and,[18] two days later, the prime minister's office announced that the Cabinet had decided not to restore the original lyrics.[19]

In May 2016, Liberal MP Mauril Bélanger introduced a private member's Bill C-210 to change two words in "O Canada".[20] These proposed changes are said to make the anthem more gender-neutral by changing the words "thy sons" to "of us". In June 2016, the bill passed its third reading with a vote of 225 to 74 in the House of Commons.[21] As of April 2017[update], the bill is being considered by the Senate.[22]

History

The original French lyrics of "O Canada" were written by Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier, to music composed by Calixa Lavallée, as a French Canadian patriotic song for the Saint-Jean-Baptiste Society and first performed on June 24, 1880, at a Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day banquet in Quebec City. At that time, the "Chant National", also by Routhier, was popular amongst Francophones as an anthem,[23] while "God Save the Queen" and "The Maple Leaf Forever" had, since 1867, been competing as unofficial national anthems in English Canada. "O Canada" joined that fray when a group of school children sang it for the 1901 tour of Canada by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall (later King George V and Queen Mary).[1]

Five years later, the Whaley and Royce company in Toronto, Ontario, published the music with the French text and a first translation into English by Thomas Bedford Richardson and, in 1908, Collier's Weekly magazine held a competition to write new English lyrics for "O Canada". The competition was won by Mercy E. Powell McCulloch, but her version never gained wide acceptance.[23] In fact, many made English translations of Routhier's words; however, the most popular version was created in 1908 by Robert Stanley Weir, a lawyer and Recorder of the City of Montreal. A slightly modified version was officially published for the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation in 1927, and gradually it became the most widely accepted and performed version of this song.[1]

The tune was thought to have become the de facto national anthem after King George VI remained at attention during its playing at the dedication of the National War Memorial in Ottawa, Ontario, on May 21, 1939;[24] though George was actually following a precedent set by his brother, Edward, the previous king of Canada, when he dedicated the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France in 1936.[25] Still, by-laws and practices governing the use of song during public events in municipalities varied; in Toronto, "God Save the Queen" was employed, while in Montreal it was "O Canada".

Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson in 1964 said one song would have to be chosen as the country's national anthem and the government resolved to form a joint committee to review the status of the two musical works. The next year, Pearson put to the House of Commons a motion that "the government be authorized to take such steps as may be necessary to provide that 'O Canada' shall be the National Anthem of Canada while 'God Save the Queen' shall be the Royal Anthem of Canada," of which parliament approved. In 1967, the Prime Minister advised Governor General Georges Vanier to appoint the Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons on the National and Royal Anthems; the group first met in February and,[26] within two months, on April 12, 1967, presented its conclusion that "O Canada" should be designated as the national anthem and "God Save the Queen" as the royal anthem of Canada,[1] one verse from each, in both official languages, to be adopted by parliament. The group was then charged with establishing official lyrics for each song. For "O Canada", the Robert Stanley Weir version of 1908 was recommended, with a few minor changes, for the English words;[27] two of the "stand on guard" phrases were replaced with "from far and wide" and "God keep our land."[1]

Still, it was not until 1970 that the Queen of Canada purchased the right to the lyrics and music of "O Canada"—from Gordon V. Thompson Music for $1[28]—and 1980 before the song finally became the official national anthem via the National Anthem Act.[25][26] The act established a religious reference to the English lyrics and the phrase "From far and wide, O Canada" to replace one of the repetitions of the phrase "We stand on guard." This change was controversial with traditionalists and, for several years afterwards, it was not uncommon to hear people still singing the old lyrics at public events. In contrast, the French version has never been changed from its original.[29]

Second and third stanzas: Historical refrain

Below are some slightly different versions of the second and third stanzas and the chorus, plus an additional fourth stanza,[1] but these are rarely sung.[30]

- O Canada! Where pines and maples grow.

- Great prairies spread and lordly rivers flow.

- How dear to us thy broad domain,

- From East to Western sea.

- Thou land of hope for all who toil!

- Thou True North, strong and free!

- Chorus:

- God keep our land glorious and free!

- O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

- O Canada, we stand on guard for thee.

- O Canada! Beneath thy shining skies

- May stalwart sons, and gentle maidens rise,

- To keep thee steadfast through the years

- From East to Western sea.

- Our own beloved native land!

- Our True North, strong and free!

- Chorus

- Ruler supreme, who hearest humble prayer,

- Hold our Dominion in thy loving care;

- Help us to find, O God, in thee

- A lasting, rich reward,

- As waiting for the better Day,

- We ever stand on guard.

- Chorus

Original French version

The first verse is the same. The other verses follow.

|

Translation: |

|

Performances

"O Canada" is routinely played before sporting events involving Canadian teams. Singers at such public events often mix the English and French lyrics to represent Canada's linguistic duality.[31] Other linguistic variations have also been performed: During the opening ceremonies of the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, "O Canada" was sung in the southern Tutchone language by Yukon native Daniel Tlen.[32][33] At a National Hockey League (NHL) game in Calgary, in February 2007, Cree singer Akina Shirt became the first person ever to perform "O Canada" in the Cree language at such an event.[34]

Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, the National Basketball Association, and the NHL all require venues to perform both the Canadian and American national anthems at games that involve teams from both countries, with the away team's anthem being performed first, followed by the host country.[35] Major League Baseball teams have played the song at games involving the Toronto Blue Jays and the former Montreal Expos,[36] and National Basketball Association teams do so for games involving the Toronto Raptors, and previously, the Vancouver Grizzlies. Major League Soccer has the anthem performed at matches involving Toronto FC, Montreal Impact, and Vancouver Whitecaps FC.

Laws and etiquette

The National Anthem Act specifies the lyrics and melody of "O Canada", placing both of them in the public domain, allowing the anthem to be freely reproduced or used as a base for derived works, including musical arrangements.[37] There are no regulations governing the performance of "O Canada", leaving citizens to exercise their best judgment. When it is performed at an event, traditional etiquette is to either start or end the ceremonies with the anthem, including situations when other anthems are played, and for the audience to stand during the performance. Civilian men usually remove their hats, while women and children are not required to do so.[38] Military men and women in uniform traditionally keep their hats on and offer the military salute during the performance of the anthem, with the salute offered in the direction of the Maple Leaf Flag if one is present, and if not present it is offered standing at attention.[38]

Adaptations

"O Canada's" melody, in the 1950s, was adapted to serve as the school anthem for the Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines, titled "A Song for Mary" or simply "The Ateneo de Manila Graduation Hymn". The lyrics were written by Rf. James B. Reuter, and the melody was adapted by Col. Jose Campaña.[39]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Department of Canadian Heritage. "Full history of "O Canada"". Government of Canada. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ DeRocco, David (2008). From sea to sea to sea : a newcomer's guide to Canada. Full Blast Productions. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-0-9784738-4-6.

- ^ Department of Canadian Heritage. "Patrimoine canadien – Hymne national du Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ Canada. Parliament, House of Commons. (1964). House of Commons debates, official report. Vol. 11. Queen's Printer. p. 11806.

- ^ http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/celebrate/pdf/National_Anthem_e.pdf

- ^ a b Colombo, John Robert (February 1995). Colombo's All-Time Great Canadian Quotations. Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-5639-6.

- ^ "Olympic mottoes borrow lines from O Canada". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. September 25, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ^ Elizabeth II (July 27, 1993). "The Coat of Arms, Emblems and the Manitoba Tartan Amendment Act". Schedule A.1 [subsection 1(3)]. Winnipeg: Queen's Printer for Manitoba. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Alberta Culture and Community Spirit – Provincial Motto, Colour and Logos". Culture.alberta.ca. June 1, 1968. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ Hymns of the Christian Life. Harrisburg: Christian Publications Inc. 1962. Number 565.

- ^ Weir, Recorder; Lavellée, C.; Grant-Schaefer, G.A. (1908). "O Canada! A National Song for Canadians" (PDF). The Delmar Music Co. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Senate of Canada (February 21, 2002). "Original O Canada Text 'an Amazing Discovery'". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Hansard". 1st Session, 37th Parliament. Ottawa: Queen's Printer for Canada. February 21, 2002. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Byers, Jim (June 6, 1990). "'O Canada' offensive, Metro says". Toronto Star. p. A.2.

- ^ Thomas, Doug (May 17, 2006). "Is Canada a Secular Nation? Part 3: Post-Charter Canada". Institute for Humanist Studies. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ Byfield, Ted (July 1, 2007). "Secular anthem lost in translation". WorldNetDaily. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ "O Canada lyrics to be reviewed". MSN. March 3, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

- ^ "English-Speaking Canadians Reject Changing Verse from "O Canada"". Angus Reid Public Opinion. March 5, 2010: 1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "National anthem won't change: PMO". CBC. March 5, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ^ "LEGISinfo - Private Member's Bill C-210 (42-1)". www.parl.gc.ca. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- ^ "Dying MP's gender-neutral O Canada bill passes final Commons vote". CBC. June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 15, 2016.

- ^ "LEGISinfo - Private Member's Bill C-210 (42-1)". www.parl.gc.ca. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Bélanger, Claude. "The Quebec History Encyclopedia". In Marianopolis College (ed.). National Anthem of Canada. Montreal: Marianopolis College. Retrieved July 5, 2010.

- ^ Bethune, Brian (July 7, 2011). "A gift fit for a king". Maclean's. Toronto: Rogers Communications. ISSN 0024-9262. Retrieved July 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Galbraith, William (1989). "Fiftieth Anniversary of the 1939 Royal Visit". Canadian Parliamentary Review. 12 (3). Ottawa: Commonwealth Parliamentary Association: 10. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ a b Potvin, Gilles; Kallmann, Helmut. "The Canadian Encyclopedia". In Marsh, James Harley (ed.). Encyclopedia of Music in Canada > Songs > 'O Canada'. Toronto: Historica Foundation of Canada. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ Kallmann, Helmut. "The Canadian Encyclopedia". In Marsh, James Harley (ed.). Encyclopedia of Music in Canada > Musical Genres > National and royal anthems. Toronto: Historica Foundation of Canada. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ Helmut Kallmann, Marlene Wehrle. "Gordon V. Thompson Music". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ "National anthem: O Canada". Canoe. May 26, 2004. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved July 6, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Office of the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta. "O Canada" (PDF). Queen's Printer for Alberta. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ "Turin Bids Arrivederci to Winter Olympics". The New York Times. Associated Press. February 26, 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2008.

- ^ "Daniel Tlen". Yukon First Nations. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ O Canada (Canada National Anthem) // Calgary 1988 Version on YouTube

- ^ "Edmonton girl to sing anthem in NHL first at Saddledome". CBC. February 1, 2007. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ Allen, Kevin (March 23, 2003). "NHL Seeks to Stop Booing For a Song". USA Today. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- ^ Wayne C. Thompson (2012). Canada 2012. Stryker Post. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-61048-884-6.

- ^ Department of Justice (2011). "National Anthem Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. N-2)". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Department of Canadian Heritage. "Anthems of Canada". Government of Canada. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "A Song For Mary". ateneo.edu. Retrieved June 14, 2015.

External links