Impeachment of Bill Clinton

The impeachment of Bill Clinton, the 42nd President of the United States, was initiated in December 1998 by the House of Representatives and led to a trial in the Senate on two charges, one of perjury and one of obstruction of justice.[1] These charges stemmed from a sexual harassment lawsuit filed against Clinton by Paula Jones. Clinton was subsequently acquitted of these charges by the Senate on February 12, 1999.[2] Two other impeachment articles – a second perjury charge and a charge of abuse of power – failed in the House.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 40th and 42nd Governor of Arkansas 42nd President of the United States Tenure Appointments Presidential campaigns

|

||

Leading to the impeachment, Independent Counsel Ken Starr turned over documentation to the House Judiciary Committee. Chief Prosecutor David Schippers and his team reviewed the material and determined there was sufficient evidence to impeach the president. As a result, four charges were considered by the full House of Representatives; two passed, making Clinton the second president to be impeached, after Andrew Johnson in 1868, and only the third against whom articles of impeachment had been brought before the full House for consideration (Richard Nixon resigned from the presidency in 1974, while an impeachment process against him was underway).

The trial in the United States Senate began right after the seating of the 106th Congress, in which the Republican Party held 55 Senate seats. A two-thirds vote (67 senators) was required to remove Clinton from office. Fifty senators voted to remove Clinton on the obstruction of justice charge and 45 voted to remove him on the perjury charge; no member of his own Democratic Party voted guilty on either charge. Clinton, like Johnson a century earlier, was acquitted on all charges.

Background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

In 1994, Paula Jones filed a lawsuit accusing Clinton of sexual harassment when he was governor of Arkansas. Clinton attempted to delay a trial until after he left office, but in May 1997 the Supreme Court unanimously ordered the case to proceed and shortly thereafter the pre-trial discovery process commenced. Jones' attorneys wanted to prove that Clinton had engaged in a pattern of behavior with women that lent support to her claims. In late 1997, Linda Tripp began secretly recording conversations with her friend Monica Lewinsky, a former intern and Department of Defense employee, in which Lewinsky divulged that she had had a sexual relationship with the President. Tripp shared this information with Paula Jones' lawyers, who put Lewinsky on their witness list in December 1997. According to the Starr report, after Lewinsky appeared on the witness list Clinton began taking steps to conceal their relationship, including suggesting she file a false affidavit, suggesting she use cover stories, concealing gifts he had given her, and helping her obtain a job to her liking.

Clinton gave a sworn deposition on January 17, 1998, where he denied having a "sexual relationship", "sexual affair" or "sexual relations" with Lewinsky. He also denied that he was ever alone with her. His lawyer, Robert S. Bennett, stated with Clinton present that Lewinsky's affidavit showed that there was no sex in any manner, shape or form between Clinton and Lewinsky. The Starr Report states that the following day, Clinton "coached" his secretary Betty Currie into repeating his denials should she be called to testify.

After rumors of the scandal reached the news, Clinton publicly stated, "I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky."[3] Months later, Clinton admitted that his relationship with Lewinsky was "wrong" and "not appropriate". Lewinsky engaged in oral sex with Clinton several times.[4][5]

The judge in the Jones case later ruled the Lewinsky matter immaterial, and threw out the case in April 1998 on the grounds that Jones had failed to show any damages. After Jones appealed, Clinton agreed in November 1998 to settle the case for $850,000 while still admitting no wrongdoing.[6]

Independent counsel investigation

The charges arose from an investigation by Ken Starr, an Independent Counsel. Originally dealing with Whitewater, Starr, with the approval of United States Attorney General Janet Reno, conducted a wide-ranging investigation of alleged abuses, including the Whitewater affair, the firing of White House travel agents, and the alleged misuse of FBI files. On January 12, 1998, Linda Tripp, who had been working with the Jones lawyers, informed Starr that Lewinsky was preparing to commit perjury in the Jones case and had asked Tripp to do the same. She also said Clinton's friend Vernon Jordan was assisting Lewinsky. Based on the connection to Jordan, who was under scrutiny in the Whitewater probe, Starr obtained approval from Reno to expand his investigation into whether Lewinsky and others were breaking the law.

A much-quoted statement from Clinton's grand jury testimony showed him questioning the precise use of the word "is". Contending that his statement that "there's nothing going on between us" had been truthful because he had no ongoing relationship with Lewinsky at the time he was questioned, Clinton said, "It depends upon what the meaning of the word 'is' is. If the—if he—if 'is' means is and never has been, that is not—that is one thing. If it means there is none, that was a completely true statement".[7] Starr obtained further evidence of inappropriate behavior by seizing the computer hard drive and email records of Monica Lewinsky. Based on the president's conflicting testimony, Starr concluded that Clinton had committed perjury. Starr submitted his findings to Congress in a lengthy document (the so-called Starr Report), and simultaneously posted the report, which included descriptions of encounters between Clinton and Lewinsky, on the Internet.[8] Starr was criticized by Democrats for spending $70 million on an investigation that substantiated only perjury and obstruction of justice.[9] Critics of Starr also contend that his investigation was highly politicized because it regularly leaked tidbits of information to the press in violation of legal ethics, and because his report included lengthy descriptions which were humiliating yet irrelevant to the legal case.[10][11]

Impeachment by House of Representatives

Since Ken Starr had already completed an extensive investigation, the House Judiciary Committee conducted no investigations of its own into Clinton's alleged wrongdoing, and it held no serious impeachment-related hearings before the 1998 midterm elections. Nevertheless, impeachment was one of the major issues in the election.

In November 1998, the Democrats picked up five seats in the House although the Republicans still maintained majority control.[12] The results were a particular embarrassment for House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who, before the election, had been reassured by private polling that Clinton's scandal would result in Republican gains of up to thirty House seats.[12] Shortly after the elections, Gingrich, who had been one of the leading advocates for impeachment,[13] announced he would resign from Congress as soon as he was able to find somebody to fill his vacant seat;[12] Gingrich fulfilled this pledge, and officially resigned from Congress on January 3, 1999.[14]

Impeachment proceedings were initiated during the post-election, "lame duck" session of the outgoing 105th United States Congress. Unlike the case of the 1974 impeachment process against Richard Nixon, the committee hearings were perfunctory but the floor debate in the whole House was spirited on both sides. The Speaker-designate, Representative Bob Livingston, chosen by the Republican Party Conference to replace Gingrich as House Speaker, announced the end of his candidacy for Speaker and his resignation from Congress from the floor of the House after his own marital infidelity came to light.[15] In the same speech, Livingston also encouraged Clinton to resign. Clinton chose to remain in office and urged Livingston to reconsider his resignation.[16] Many other prominent Republican members of Congress (including Dan Burton[15] of Indiana, Helen Chenoweth[15] of Idaho and Henry Hyde[15] of Illinois, the chief House manager of Clinton's trial in the Senate) had infidelities exposed about this time, all of whom voted for impeachment. Publisher Larry Flynt offered a reward for such information, and many supporters of Clinton accused Republicans of hypocrisy.[15]

Although proceedings were delayed due to the bombing of Iraq, on the passage of H. Res. 611, Clinton was impeached on December 19, 1998, by the House of Representatives on grounds of perjury to a grand jury (by a 228–206 vote)[17] and obstruction of justice (by a 221–212 vote).[18] Two other articles of impeachment failed – a second count of perjury in the Jones case (by a 205–229 vote)[19] and one accusing Clinton of abuse of power (by a 148–285 vote).[20] Clinton thus became the second U.S. president to be impeached, following Andrew Johnson in 1868. (Clinton was the third sitting president against whom the House of Representatives initiated impeachment proceedings since 1789.)

Five Democrats (Virgil Goode of Virginia, Ralph Hall of Texas, Paul McHale of Pennsylvania, Charles Stenholm of Texas and Gene Taylor of Mississippi) voted in favor of three of the four articles of impeachment, but only Taylor voted for the abuse of power charge. Five Republicans (Amo Houghton of New York, Peter King of New York, Connie Morella of Maryland, Chris Shays of Connecticut and Mark Souder of Indiana) voted against the first perjury charge. Eight more Republicans (Sherwood Boehlert of New York, Michael Castle of Delaware, Phil English of Pennsylvania, Nancy Johnson of Connecticut, Jay Kim of California, Jim Leach of Iowa, John McHugh of New York and Ralph Regula of Ohio), but not Souder, voted against the obstruction charge. Twenty-eight Republicans voted against the second perjury charge, sending it to defeat, and eighty-one voted against the abuse of power charge.

Article I charged that Clinton lied to the grand jury concerning:[21]

- the nature and details of his relationship with Lewinsky

- prior false statements he made in the Jones deposition

- prior false statements he allowed his lawyer to make characterizing Lewinsky's affidavit

- his attempts to tamper with witnesses

Article III charged Clinton with attempting to obstruct justice in the Jones case by:[22]

- encouraging Lewinsky to file a false affidavit

- encouraging Lewinsky to give false testimony if and when she was called to testify

- concealing gifts he had given to Lewinsky that had been subpoenaed

- attempting to secure a job for Lewinsky to influence her testimony

- permitting his lawyer to make false statements characterizing Lewinsky's affidavit

- attempting to tamper with the possible testimony of his secretary Betty Curie

- making false and misleading statements to potential grand jury witnesses

Acquittal by the Senate

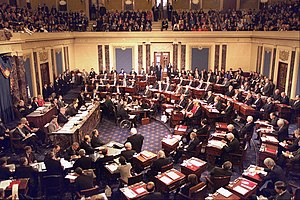

The Senate trial began on January 7, 1999, with Chief Justice of the United States William Rehnquist presiding. The first day consisted of formal presentation of the charges against Clinton, and of Rehnquist swearing in all arguants in the trial.

Thirteen House Republicans from the Judiciary Committee served as "managers", the equivalent of prosecutors:

- Chairman Henry Hyde of Illinois

- Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin

- Bill McCollum of Florida

- George Gekas of Pennsylvania

- Charles Canady of Florida

- Steve Buyer of Indiana

- Ed Bryant of Tennessee

- Steve Chabot of Ohio

- Bob Barr of Georgia

- Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas

- Chris Cannon of Utah

- James E. Rogan of California

- Lindsey Graham of South Carolina

Clinton was defended by Cheryl Mills. Clinton's counsel staff included Charles Ruff, David E. Kendall, Dale Bumpers, Bruce Lindsey, Nicole Seligman, Lanny A. Breuer and Gregory B. Craig.[23]

A resolution on rules and procedure for the trial was adopted unanimously on the following day; however, senators tabled the question of whether to call witnesses in the trial. The trial remained in recess while briefs were filed by the House (January 11) and Clinton (January 13).

The managers presented their case over three days, from January 14 to 16, with discussion of the facts and background of the case; detailed cases for both articles of impeachment (including excerpts from videotaped grand jury testimony that Clinton had made the previous August); matters of interpretation and application of the laws governing perjury and obstruction of justice; and argument that the evidence and precedents justified removal of the President from office by virtue of "willful, premeditated, deliberate corruption of the nation's system of justice through perjury and obstruction of justice."[24] The defense presentation took place from January 19–21. Clinton's defense counsel argued that Clinton's grand jury testimony had too many inconsistencies to be a clear case of perjury, that the investigation and impeachment had been tainted by partisan political bias, that the President's approval rating of more than 70 percent indicated that his ability to govern had not been impaired by the scandal, and that the managers had ultimately presented "an unsubstantiated, circumstantial case that does not meet the constitutional standard to remove the President from office".[24] January 22 and 23 were devoted to questions from members of the Senate to the House managers and Clinton's defense counsel. Under the rules, all questions (over 150) were to be written down and given to Rehnquist to read to the party being questioned.

On January 25, Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia moved for dismissals of both articles of impeachment for lack of merit. On the following day, Rep. Bryant moved to call witnesses to the trial, a question that the Senate had scrupulously avoided to that point. In both cases, the Senate voted to deliberate on the question in private session, rather than public, televised procedure. On January 27, the Senate voted on both motions in public session; the motion to dismiss failed on a nearly party line vote of 56–44, while the motion to depose witnesses passed by the same margin. A day later, the Senate voted down motions to move directly to a vote on the articles of impeachment and to suppress videotaped depositions of the witnesses from public release, Feingold again voting with the Republicans.

Over three days, February 1–3, House managers took videotaped closed-door depositions from Monica Lewinsky, Clinton's friend Vernon Jordan, and White House aide Sidney Blumenthal. On February 4, however, the Senate voted 70–30 that excerpting these videotapes would suffice as testimony, rather than calling live witnesses to appear at trial. The videos were played in the Senate on February 6, featuring 30 excerpts of Lewinsky discussing her affidavit in the Paula Jones case, the hiding of small gifts Clinton had given her, and his involvement in procurement of a job for Lewinsky.

On February 8, closing arguments were presented with each side allotted a three-hour time slot. On the President's behalf, White House Counsel Charles Ruff declared:

There is only one question before you, albeit a difficult one, one that is a question of fact and law and constitutional theory. Would it put at risk the liberties of the people to retain the President in office? Putting aside partisan animus, if you can honestly say that it would not, that those liberties are safe in his hands, then you must vote to acquit.[24]

Chief Prosecutor Henry Hyde countered:

A failure to convict will make the statement that lying under oath, while unpleasant and to be avoided, is not all that serious ... We have reduced lying under oath to a breach of etiquette, but only if you are the President ... And now let us all take our place in history on the side of honor, and, oh, yes, let right be done.[24]

On February 9, after voting against a public deliberation on the verdict, the Senate began closed-door deliberations instead. On February 12, the Senate emerged from its closed deliberations and voted on the articles of impeachment. A two-thirds vote, 67 votes, would have been necessary to convict and remove the President from office. The perjury charge was defeated with 45 votes for conviction and 55 against.[25] (Senator Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania voted "not proved" for both charges,[26] which was considered by Chief Justice Rehnquist to constitute a vote of "not guilty".) The obstruction of justice charge was defeated with 50 for conviction and 50 against.[27]

Senate votes

All 45 Democrats in the Senate voted "not guilty" on both charges. The five Republican senators who voted against conviction on both charges were John Chafee of Rhode Island, Susan Collins of Maine, Jim Jeffords of Vermont, Olympia Snowe of Maine, and Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania. Specter, who said he was not prepared to cast a guilty or not guilty vote, voted "not proved", which was counted as a not guilty vote.[28] The additional five Republican senators who voted "not guilty" only on the perjury charge were Slade Gorton of Washington, Richard Shelby of Alabama, Ted Stevens of Alaska, Fred Thompson of Tennessee, and John Warner of Virginia.

| State | Senator | Party[note 1] | Perjury charge | Obstruction of justice charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michigan | Spencer Abraham | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Hawaii | Daniel Akaka | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Colorado | Wayne Allard | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Missouri | John Ashcroft | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Montana | Max Baucus | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Indiana | Evan Bayh | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Utah | Robert Bennett | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Delaware | Joe Biden | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| New Mexico | Jeff Bingaman | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Missouri | Kit Bond | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| California | Barbara Boxer | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Louisiana | John Breaux | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Kansas | Sam Brownback | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Nevada | Richard Bryan | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Kentucky | Jim Bunning | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Montana | Conrad Burns | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| West Virginia | Robert Byrd | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Colorado | Ben Nighthorse Campbell | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Rhode Island | John Chafee | R | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Georgia | Max Cleland | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Mississippi | Thad Cochran | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Maine | Susan Collins | R | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| North Dakota | Kent Conrad | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Georgia | Paul Coverdell | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Idaho | Larry Craig | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Idaho | Mike Crapo | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| South Dakota | Tom Daschle | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Ohio | Mike DeWine | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Connecticut | Chris Dodd | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| North Dakota | Byron Dorgan | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| New Mexico | Pete Domenici | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Illinois | Dick Durbin | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| North Carolina | John Edwards | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Wyoming | Mike Enzi | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Wisconsin | Russ Feingold | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| California | Dianne Feinstein | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Illinois | Peter Fitzgerald | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Tennessee | Bill Frist | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Washington | Slade Gorton | R | Not guilty | Guilty |

| Florida | Bob Graham | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Texas | Phil Gramm | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Minnesota | Rod Grams | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Iowa | Chuck Grassley | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| New Hampshire | Judd Gregg | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Nebraska | Chuck Hagel | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Iowa | Tom Harkin | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Utah | Orrin Hatch | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| North Carolina | Jesse Helms | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| South Carolina | Ernest Hollings | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Arkansas | Tim Hutchinson | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Texas | Kay Bailey Hutchison | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Oklahoma | Jim Inhofe | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Hawaii | Daniel Inouye | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Vermont | Jim Jeffords | R | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| South Dakota | Tim Johnson | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Massachusetts | Ted Kennedy | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Nebraska | Bob Kerrey | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Massachusetts | John Kerry | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Wisconsin | Herb Kohl | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Arizona | Jon Kyl | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Louisiana | Mary Landrieu | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| New Jersey | Frank Lautenberg | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Vermont | Patrick Leahy | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Michigan | Carl Levin | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Connecticut | Joe Lieberman | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Arkansas | Blanche Lincoln | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Mississippi | Trent Lott | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Indiana | Richard Lugar | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Florida | Connie Mack III | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Arizona | John McCain | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Kentucky | Mitch McConnell | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Maryland | Barbara Mikulski | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| New York | Daniel Patrick Moynihan | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Alaska | Frank Murkowski | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Washington | Patty Murray | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Oklahoma | Don Nickles | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Rhode Island | Jack Reed | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Nevada | Harry Reid | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Virginia | Charles Robb | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Kansas | Pat Roberts | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| West Virginia | Jay Rockefeller | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Delaware | William V. Roth, Jr. | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Pennsylvania | Rick Santorum | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Maryland | Paul Sarbanes | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| New York | Chuck Schumer | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Alabama | Jeff Sessions | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Alabama | Richard Shelby | R | Not guilty | Guilty |

| New Hampshire | Robert C. Smith | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Oregon | Gordon Smith | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Maine | Olympia Snowe | R | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Pennsylvania | Arlen Specter | R | Not guilty[note 2] | Not guilty[note 2] |

| Alaska | Ted Stevens | R | Not guilty | Guilty |

| Wyoming | Craig L. Thomas | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Tennessee | Fred Thompson | R | Not guilty | Guilty |

| South Carolina | Strom Thurmond | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| New Jersey | Robert Torricelli | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Virginia | John Warner | R | Not guilty | Guilty |

| Ohio | George Voinovich | R | Guilty | Guilty |

| Minnesota | Paul Wellstone | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Oregon | Ron Wyden | D | Not guilty | Not guilty |

| Total votes: | Not guilty: 55 Guilty: 45 |

Not guilty: 50 Guilty: 50 | ||

- Notes:

- ^ D = Democrat; R = Republican.

- ^ a b Specter announced his vote as "not proved", a verdict used in Scots law. His vote was recorded as "not guilty" at the direction of the Chief Justice.

Results

Contempt of court citation

In April 1999, about two months after being acquitted by the Senate, Clinton was cited by Federal District Judge Susan Webber Wright for civil contempt of court for his "willful failure" to obey her repeated orders to testify truthfully in the Paula Jones sexual harassment lawsuit. For this citation, Clinton was assessed a $90,000 fine, and the matter was referred to the Arkansas Supreme Court to see if disciplinary action would be appropriate.[29]

Regarding Clinton's January 17, 1998, deposition where he was placed under oath, the judge wrote:

Simply put, the president's deposition testimony regarding whether he had ever been alone with Ms. (Monica) Lewinsky was intentionally false, and his statements regarding whether he had ever engaged in sexual relations with Ms. Lewinsky likewise were intentionally false ...[29]

On the day before leaving office in January 2001, President Clinton agreed to a five-year suspension of his Arkansas law license as part of an agreement with the independent counsel[clarification needed] to end the investigation.[30] Clinton was automatically suspended from the United States Supreme Court bar as a result of his law license suspension. However, as is customary, he was allowed 40 days to appeal an otherwise-automatic disbarment. The former President resigned from the Supreme Court bar during the 40-day appeals period.[31]

Civil settlement with Paula Jones

Eventually, the court dismissed the Paula Jones harassment lawsuit, before trial, on the grounds that Jones failed to demonstrate any damages. However, while the dismissal was on appeal, Clinton entered into an out-of-court settlement by agreeing to pay Jones $850,000.[32][33]

Political ramifications

Polls conducted during 1998 and early 1999 showed that only about one-third of Americans supported Clinton's impeachment or conviction. However, one year later, when it was clear that House impeachment would not lead to the ousting of the President, half of Americans said in a CNN/USA Today/Gallup poll that they supported impeachment but 57% approved of the Senate's decision to keep him in office and two thirds of those polled said the impeachment was harmful to the country.[34]

While Clinton's job approval rating rose during the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal and subsequent impeachment, his poll numbers with regard to questions of honesty, integrity and moral character declined.[35] As a result, "moral character" and "honesty" weighed heavily in the next presidential election. According to The Daily Princetonian, after the 2000 presidential election, "post-election polls found that, in the wake of Clinton-era scandals, the single most significant reason people voted for Bush was for his moral character."[36][37][38] According to an analysis of the election by Stanford University:

A more political explanation is the belief in Gore campaign circles that disapproval of President Clinton's personal behavior was a serious threat to the vice president's prospects. Going into the election the one negative element in the public's perception of the state of the nation was the belief that the country was morally on the wrong track, whatever the state of the economy or world affairs. According to some insiders, anything done to raise the association between Gore and Clinton would have produced a net loss of support—the impact of Clinton's personal negatives would outweigh the positive impact of his job performance on support for Gore. Thus, hypothesis four suggests that a previously unexamined variable played a major role in 2000—the retiring president's personal approval.[39]

The Stanford analysis, however, presented different theories and mainly argued that Gore had lost because he decided to distance himself from Clinton during the campaign. The writers of it concluded:[39]

We find that Gore's oft-criticized personality was not a cause of his under-performance. Rather, the major cause was his failure to receive a historically normal amount of credit for the performance of the Clinton administration ... [and] failure to get normal credit reflected Gore's peculiar campaign which in turn reflected fear of association with Clinton's behavior.[39]

According to the America's Future Foundation:

In the wake of the Clinton scandals, independents warmed to Bush's promise to 'restore honor and dignity to the White House'. According to Voter News Service, the personal quality that mattered most to voters was 'honesty'. Voters who chose 'honesty' preferred Bush over Gore by over a margin of five to one. Forty Four percent of Americans said the Clinton scandals were important to their vote. Of these, Bush reeled in three out of every four.[40]

Political commentators have argued that Gore's refusal to have Clinton campaign with him was a bigger liability to Gore than Clinton's scandals.[39][41][42][43][44] The 2000 US Congressional election also saw the Democrats gain more seats in Congress.[45] As a result of this gain, control of the US Senate was split 50–50 between both parties,[46] and Democrats would gain control over the US Senate after Republican Senator Jim Jeffords defected from his party in the spring of 2001 and agreed to caucus with the Democrats.[47]

Al Gore reportedly confronted Clinton after the election, and "tried to explain that keeping Clinton under wraps [during the campaign] was a rational response to polls showing swing voters were still mad as hell over the Year of Monica". According to the AP, "during the one-on-one meeting at the White House, which lasted more than an hour, Gore used uncommonly blunt language to tell Clinton that his sex scandal and low personal approval ratings were a hurdle he could not surmount in his campaign ... [with] the core of the dispute was Clinton's lies to Gore and the nation about his affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky."[48][49][50] Clinton, however, was unconvinced by Gore's argument and insisted to Gore that he would have won the election if he had embraced the administration and its good economic record.[48][49][50]

Ensuing events for 13 House managers

Of the 13 members of the House who managed Clinton's trial in the Senate, one lost to a Democrat in his 2000 bid for re-election (James E. Rogan, to Adam Schiff). Charles Canady retired from Congress in 2000, following through on a previous term limits pledge to voters, and Bill McCollum ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate. Asa Hutchinson, after being re-elected in 2000, left Congress after being appointed head of the Drug Enforcement Administration by President George W. Bush. In 2014, Hutchinson was elected governor of Arkansas. In 2002, two former House managers lost their seats after redistricting placed them in the same district as another incumbent (Bob Barr lost to John Linder in a Republican primary, and George Gekas lost to Democrat Tim Holden), while two more ran for the U.S. Senate (Lindsey Graham successfully, Ed Bryant unsuccessfully). The other five remained in the House well into the 2000s (decade), and two (Jim Sensenbrenner and Steve Chabot) are still members (although Chabot lost his seat to Steve Driehaus in the 2008 elections; Chabot defeated Driehaus in a 2010 rematch). In 2009, Sensenbrenner served again as a manager for the impeachment of Judge Samuel B. Kent of Texas[51] as well as serving in 2010 as Republican lead manager in the impeachment of Judge Thomas Porteous of Louisiana.[52]

See also

- Impeachment of Andrew Johnson

- Impeachment process against Richard Nixon

- List of federal political scandals in the United States

- List of federal political sex scandals in the United States

- Second-term curse

- Sexual misconduct allegations against Bill Clinton

References

- ^ Erskine, Daniel H. (2008). "The Trial of Queen Caroline and the Impeachment of President Clinton: Law As a Weapon for Political Reform". Washington University Global Studies Law Review. 7 (1). ISSN 1546-6981.

- ^ Baker, Peter (February 13, 1999). "The Senate Acquits President Clinton". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Co. Retrieved December 4, 2013.

- ^ "What Clinton Said". The Washington Post. September 2, 1998. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ "The Stained Blue Dress that Almost Lost a Presidency". University of Missouri-Kansas School of Law. Archived from the original on July 3, 2008. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ross, Brian (March 19, 1998). "Hillary at White House on 'Stained Blue Dress' Day – Schules Reviewed by ABC Show Hillary May Have Been in the White House When the Fateful Act Was Committed". ABC News. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- ^ Baker, Peter (November 14, 1998). "Clinton Settles Paula Jones Lawsuit for $850,000". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ^ "Starr Report: Narrative". Nature of President Clinton's Relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. May 19, 2004. Archived from the original on December 3, 2000. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Starr report puts Internet into overdrive". CNN. September 12, 1998. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Report: The Independent Counsel's Final Report". Aim.org. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "News leaks prompt lawyer to seek sanctions against Starr's Office". Thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Palermo, Joseph A. (March 28, 2008). "The Starr Report: How To Impeach A President (Repeat)". Huffington Post. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ a b c Gibbs, Nancy; Duffy, Michael (November 16, 1998). "Fall Of The House Of Newt". Time. Retrieved May 5, 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ JAKE TAPPER (@jaketapper) (March 9, 2007). "Gingrich Admits to Affair During Clinton Impeachment – ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Special election set to replace Gingrich". Ocala Star-Banner. January 5, 1999 – via Google News archive.

- ^ a b c d e Kurtz, Howard, "Larry Flynt, Investigative Pornographer", The Washington Post, December 19, 1998. Page C01. Retrieved 21-June-2010.

- ^ Karl, Jonathan; Associated Press (December 19, 1998). "Livingston bows out of the speakership". All Politics. CNN. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 543". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 545". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 544". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Miller, Lorraine C. (December 19, 1998). "Final vote results for roll call 546". Office of the Clerk. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Text of Article I Washington Post December 20, 1998

- ^ Text of Article IIII Washington Post December 20, 1998

- ^ Defense Who's Who, The Washington Post, January 19, 1999.

- ^ a b c d The History Place (2000). "The History Place – Impeachment: Bill Clinton". The History Place. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Senate LIS (February 12, 1999). "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress – 1st Session: vote number 17 – Guilty or Not Guilty (Art I, Articles of Impeachment v. President W. J. Clinton )". United States Senate. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Specter, Arlen (February 12, 1999). "Sen. Specter's closed-door impeachment statement". CNN. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

My position in the matter is that the case has not been proved. I have gone back to Scottish law where there are three verdicts: guilty, not guilty, and not proved. I am not prepared to say on this record that President Clinton is not guilty. But I am certainly not prepared to say that he is guilty. There are precedents for a Senator voting present. I hope that I will be accorded the opportunity to vote not proved in this case. ... But on this record, the proofs are not present. Juries in criminal cases under the laws of Scotland have three possible verdicts: guilty, not guilty, not proved. Given the option in this trial, I suspect that many Senators would choose 'not proved' instead of 'not guilty'.

That is my verdict: not proved. The President has dodged perjury by calculated evasion and poor interrogation. Obstruction of justice fails by gaps in the proofs. - ^ Senate LIS (February 12, 1999). "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 106th Congress – 1st Session: vote number 18 – Guilty or Not Guilty (Art II, Articles of Impeachment v. President W. J. Clinton )". United States Senate. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- ^ Specter, Arlen (February 12, 1999). "Sen. Specter's closed-door impeachment statement". CNN. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

My position in the matter is that the case has not been proved. I have gone back to Scottish law where there are three verdicts: guilty, not guilty, and not proved. I am not prepared to say on this record that President Clinton is not guilty. But I am certainly not prepared to say that he is guilty. There are precedents for a Senator voting present. I hope that I will be accorded the opportunity to vote not proved in this case. [...] But on this record, the proofs are not present. Juries in criminal cases under the laws of Scotland have three possible verdicts: guilty, not guilty, not proved. Given the option in this trial, I suspect that many Senators would choose 'not proved' instead of 'not guilty'.

That is my verdict: not proved. The President has dodged perjury by calculated evasion and poor interrogation. Obstruction of justice fails by gaps in the proofs. - ^ a b Clinton found in civil contempt for Jones testimony – April 12, 1999 Archived April 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Neal v. Clinton, Civ. No. 2000-5677, Agreed Order of Discipline (Ark. Cir. Ct. January 19, 2001) ("Mr. Clinton admits and acknowledges ... that his discovery responses interfered with the conduct of the Jones case by causing the court and counsel for the parties to expend unnecessary time, effort, and resources ...").

- ^ US Supreme Court Order. FindLaw. November 13, 2001.

- ^ "Jones v. Clinton finally settled". CNN. November 13, 1998. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ "Clinton-Jones Settlement Text". CNN. November 13, 1998.

- ^ Keating Holland. "A year after Clinton impeachment, public approval grows of House decision". CNN. December 16, 1999.

- ^ David S. Broder, Richard Morin (August 23, 1998). "American Voters See Two Very Different Bill Clintons". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- ^ Deborah Arotsky (May 7, 2004). "Singer authors book on the role of ethics in Bush presidency". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Stephen E. Sachs (November 7, 2000). "Of Candidates and Character". The Harvard Crimson.

- ^ Bishin, B. G.; Stevens, D.; Wilson, C. (Summer 2006). "Character Counts?: Honesty and Fairness in Election 2000" (PDF). Public Opinion Quarterly. 70 (2): 235–48. doi:10.1093/poq/nfj016.

- ^ a b c d Fiorina, M.; Abrams, S.; Pope, J. (March 2003). "The 2000 U.S. Presidential Election: Can Retrospective Voting Be Saved?" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 33 (2). Cambridge University Press: 163–87. doi:10.1017/S0007123403000073.

- ^ Todd J. Weiner (May 15, 2004). "Blueprint for Victory". America's Future Foundation.

- ^ "S/R 25: Gore's Defeat: Don't Blame Nader (Marable)". Greens.org. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Jacob Weisberg (November 8, 2000). "Why Gore (Probably) Lost – Jacob Weisberg – Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "An anatomy of 2000 USA presidential election". Nigerdeltacongress.com. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ "Beyond the Recounts: Trends in the 2000 US Presidential Election". Cairn.info. November 12, 2000. Retrieved May 23, 2011.

- ^ Ripley, Amanda (November 20, 2000). "Election 2000: TOM DASCHLE, SENATE MINORITY LEADER: Partisan from the Prairie". Time. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (November 9, 2000). "THE 2000 ELECTIONS: THE SENATE; Democrats Gain Several Senate Seats, but Republicans Retain Control". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ "The Crist Switch: Top 10 Political Defections". Time. April 29, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Margaret Carlson (February 11, 2001). "When a Buddy Movie Goes Bad". Time.

- ^ a b "Clinton and Gore have it out". Associated Press. February 8, 2001. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Harris, John F. (February 7, 2001). "Blame divides Gore, Clinton". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Sensenbrenner, House Vote to Impeach Judge Kent of Texas" (Press release). Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner. June 19, 2009. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

After voting to impeach, Sensenbrenner was selected to serve as one of the five House Managers who will try the case in the Senate.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sensenbrenner to Serve as House Manager for Porteous Impeachment" (Press release). Congressman Jim Sensenbrenner. March 11, 2010. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

Sensenbrenner was selected to serve as one of the five House Managers who will try the case in the Senate after the resolution passed.

{{cite press release}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- "Articles of Impeachment and Judiciary Committee Roll Call Votes". The Washington Post. (December 19, 1998)

- "The Articles Explained". The Washington Post. (December 18, 1998.) Archived August 16th, 2000 from the original link.

- "The Starr Report", The Washington Post (September 16, 1998)

- "What Clinton Said", The Washington Post (September 2, 1998)

- "Impeachment of William Jefferson Clinton, President of the United States, Report of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, together with additional, minority, and dissenting views" (H. Rpt. 105-830) (440 pages), December 16, 1998

- "Dale Bumpers: Closing Defense Arguments - Impeachment Trial of William J. Clinton"

- Famous Trials: The Impeachment Trial of President William Clinton, University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School