Porto

Porto

Oporto | |

|---|---|

From the top left corner clockwise: Clérigos Tower; Palácio da Bolsa; Avenida dos Aliados; Church of São Francisco; Porto Cathedral; Porto City Hall; Ribeira | |

| Etymology: Error: {{language with name/for}}: missing language tag or language name (help) | |

| Nickname(s): A Cidade Invicta ("The Unvanquished City"), A Cidade da Virgem ("The City of the Virgin") | |

| Motto(s): Antiga, Mui Nobre, Sempre Leal e Invicta (Old, Most Noble, Always Loyal and Unvanquished) | |

| Coordinates: 41°9′43.71″N 8°37′19.03″W / 41.1621417°N 8.6219528°W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Norte |

| Subregion | Grande Porto |

| District | Porto |

| Settlement | 275 BOT |

| Municipality | 868 |

| Civil parishes | 7 |

| Government | |

| • Type | LAU |

| • Body | Concelho/Câmara Municipal |

| • Mayor | Rui Moreira |

| • Municipal Chair | Miguel Pereira Leite |

| Area | |

| • Total | 41.42 km2 (15.99 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 104 m (341 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 287,591 |

| • Density | 6,900/km2 (18,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (WEST) |

| Postal Zone | 4000-286 Porto |

| Area code | (+351) 22[1] |

| Demonym | Portuense |

| Patron Saint | Nossa Senhora de Vandoma |

| Municipal Holidays | 24 June (São João) |

| Website | www |

| Geographic detail from CAOP (2010)[2] produced by Instituto Geográfico Português (IGP) | |

| Official name | Historic Centre of Porto |

| Criteria | iv |

| Reference | 755 |

| Inscription | 1996 (20th Session) |

Porto,[a] in English traditionally Oporto,[b][7] is the second-largest city in Portugal after Lisbon[8] and one of the major urban areas of the Iberian Peninsula. The city proper has a population of 287,591 and the metropolitan area of Porto, which extends beyond the administrative limits of the city, has a population of 2.3 million (2011)[9] in an area of 2,395 km2 (925 sq mi),[10] making it the second-largest urban area in Portugal.[11][12][13] It is recognized as a gamma-level global city by the Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Study Group,[14] the only Portuguese city besides Lisbon to be recognised as a global city.

Located along the Douro River estuary in northern Portugal, Porto is one of the oldest European centres, and its historical core was proclaimed a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. The western part of its urban area extends to the coastline of the Atlantic Ocean. Its settlement dates back many centuries, when it was an outpost of the Roman Empire. Its combined Celtic-Latin name, Portus Cale,[15] has been referred to as the origin of the name Portugal, based on transliteration and oral evolution from Latin. In Portuguese, the name of the city includes a definite article: o Porto ("the port") which is where its English name "Oporto" comes from.[16]

Port wine, one of Portugal's most famous exports, is named after Porto, since the metropolitan area, and in particular the cellars of Vila Nova de Gaia, were responsible for the packaging, transport, and export of fortified wine.[17] In 2014 and 2017, Porto was elected The Best European Destination by the Best European Destinations Agency.[18] Porto is on the Portuguese Way path of the Camino de Santiago.

History

Early history

The history of Porto dates back to around 300 BC with Proto-Celtic and Celtic people being the first known inhabitants. Ruins of that period have been discovered in several areas.

During the Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, the city developed as an important commercial port, primarily in the trade between Olissipona (the modern Lisbon) and Bracara Augusta (the modern Braga)[19]. Porto was also important during the Suebian and Visigothic times, and a centre for the expansion of Christianity during that period.[20]

Porto fell under the control of the Moors during the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula in 711.[21] In 868, Vímara Peres, an Asturian count from Gallaecia, and a vassal of the King of Asturias, Léon and Galicia, Alfonso III, was sent to reconquer and secure the lands back into Christian hands. This included the area from the Minho to the Douro River: the settlement of Portus Cale and the area that is known as Vila Nova de Gaia. Portus Cale, later referred to as Portucale, was the origin for the modern name of Portugal.[22] In 868, Count Vímara Peres established the County of Portugal, or (Template:Lang-pt), usually known as Condado Portucalense after reconquering the region north of Douro.[19]

In 1387, Porto was the site of the marriage of John I of Portugal and Philippa of Lancaster, daughter of John of Gaunt; this symbolized a long-standing military alliance between Portugal and England.[23] The Portuguese-English alliance (see the Treaty of Windsor) is the world's oldest recorded military alliance.[24][25]

In the 14th and the 15th centuries, Porto's shipyards contributed to the development of Portuguese shipbuilding. Also from the port of Porto, in 1415, Prince Henry the Navigator (son of John I of Portugal) embarked on the conquest of the Moorish port of Ceuta, in northern Morocco.[26][27] This expedition by the king and his fleet, which counted among others, Prince Henry, was followed by navigation and exploration along the western coast of Africa, initiating the Portuguese Age of Discovery. The nickname given to the people of Porto began in those days; Portuenses are to this day, colloquially, referred to as tripeiros (Template:Lang-en), referring to this period of history, when higher-quality cuts of meat were shipped from Porto with their sailors, while off-cuts and byproducts, such as tripe, were left behind for the citizens of Porto; tripe remains a culturally important dish in modern-day Porto.

18th century

Wine, produced in the Douro valley, was already in the 13th century transported to Porto in barcos rabelos (flat sailing vessels). In 1703, the Methuen Treaty established the trade relations between Portugal and England.[28] In 1717, a first English trading post was established in Porto. The production of port wine then gradually passed into the hands of a few English firms. To counter this English dominance, Prime Minister Marquis of Pombal established a Portuguese firm receiving the monopoly of the wines from the Douro valley. He demarcated the region for production of port, to ensure the wine's quality; this was the first attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe.[citation needed] The small winegrowers revolted against his strict policies on Shrove Tuesday, burning down the buildings of this firm. The revolt was called Revolta dos Borrachos (revolt of the drunks).

Between 1732 and 1763, Italian architect Nicolau Nasoni designed a baroque church with a tower that became its architectural and visual icon: the Torre dos Clérigos (English: Clerics' Tower). During the 18th and 19th centuries, the city became an important industrial centre and had its size and population increase.

19th century

The invasion of the Napoleonic troops in Portugal under Marshal Soult also brought war to the city of Porto. On 29 March 1809, as the population fled from the advancing French troops[29][30] and tried to cross the river Douro over the Ponte das Barcas (a pontoon bridge), the bridge collapsed under the weight. This event is still remembered by a plate at the Ponte D. Luis I. The French army was rooted out of Porto by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, when his Anglo-Portuguese Army crossed the Douro River from the Mosteiro da Serra do Pilar (a former convent) in a brilliant daylight coup de main, using wine barges to transport the troops, so outflanking the French Army.[31]

On 24 August 1820, a liberal revolution occurred, quickly spreading without resistance to the rest of the country.[32] In 1822, a liberal constitution was accepted, partly through the efforts of the liberal assembly of Porto (Junta do Porto). When Miguel I of Portugal took the Portuguese throne in 1828, he rejected this constitution and reigned as an absolutist monarch.[33] A Civil War was then fought from 1828 to 1834 between those supporting Constitutionalism, and those opposed to this change, keen on near-absolutism and led by D. Miguel. Porto rebelled again and had to undergo a siege of eighteen months between 1832 and 1833 by the absolutist army.[34] Porto is also called "Cidade Invicta" (English: Unvanquished City) after successfully resisting the Miguelist siege. After the abdication of King Miguel, the liberal constitution was re-established.

Known as the city of bridges, Porto built its first permanent bridge, the Ponte das Barcas (a pontoon bridge), in 1806. Three years later, it collapsed under the weight of thousands of fugitives from the French invasions during the Peninsular War, causing thousands of deaths.[35] It was replaced by the Ponte D. Maria II, popularised under the name Ponte Pênsil (suspended bridge) and built between 1841–43; only its supporting pylons have remained.

The Ponte D. Maria, a railway bridge, was inaugurated on 4 November of that same year;[36] it was considered a feat of wrought iron engineering and was designed by Gustave Eiffel, notable for his Parisian tower. The later Ponte Dom Luís I replaced the aforementioned Ponte Pênsil.[37] This last bridge was made by Teophile Seyrig, a former partner of Eiffel. Seyrig won a governmental competition that took place in 1879. Building began in 1881 and the bridge was opened to the public on 31 October 1886.[38]

A higher-learning institution in nautical sciences (Aula de Náutica, 1762) and a stock exchange (Bolsa do Porto, 1834) were established in the city, but were discontinued later.[when?]

Unrest by Republicans led to the first revolt against the monarchy in Porto on 31 January 1891. This resulted ultimately in the overthrow of the monarchy and proclamation of the republic by the 5 October 1910 revolution.[39][40][41]

20th century

On 19 January 1919, forces favorable to the restoration of the monarchy launched a counter-revolution in Porto known as Monarchy of the North.[42][43] During this time, Porto was the capital of the restored kingdom, as the movement was contained to the north. The monarchy was deposed less than a month later and no other monarchist revolution in Portugal happened again.

The historic centre of Porto was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1996. The World Heritage Site is defined in two concentric zones; the "Protected area", and within it the "Classified area". The Classified area comprises the medieval borough located inside the 14th-century Romanesque wall.[44]

Geography

In 1996, UNESCO recognised Porto's historic centre as a World Heritage Site.[19] Among the architectural highlights of the city, Porto Cathedral is the oldest surviving structure, together with the small romanesque Church of Cedofeita, the gothic Igreja de São Francisco (Church of Saint Francis), the remnants of the city walls and a few 15th-century houses. The baroque style is well represented in the city in the elaborate gilt work interior decoration of the churches of St. Francis and St. Claire (Santa Clara), the churches of Mercy (Misericórdia) and of the Clerics (Igreja dos Clérigos), the Episcopal Palace of Porto, and others. The neoclassicism and romanticism of the 19th and 20th centuries also added interesting monuments to the landscape of the city, like the magnificent Stock Exchange Palace (Palácio da Bolsa), the Hospital of Saint Anthony, the Municipality, the buildings in the Liberdade Square and the Avenida dos Aliados, the tile-adorned São Bento Train Station and the gardens of the Crystal Palace (Palácio de Cristal). A guided visit to the Palácio da Bolsa, and in particular the Arab Room, is a major tourist attraction.

Many of the city's oldest houses are at risk of collapsing. The population in Porto municipality dropped by nearly 100,000 since the 1980s, but the number of permanent residents in the outskirts and satellite towns has grown strongly.[45]

Administratively, the municipality is divided into 7 civil parishes (freguesias):[46]

- Aldoar, Foz do Douro e Nevogilde

- Bonfim

- Campanhã

- Cedofeita, Santo Ildefonso, Sé, Miragaia, São Nicolau e Vitória

- Lordelo do Ouro e Massarelos

- Paranhos

- Ramalde

Climate

Porto features a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb), with influences of an oceanic climate (Cfb) like the north of Spain.[47] As a result, its climate shares many characteristics with the coastal south: warm, dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Cool and rainy days can, occasionally, interrupt the dry season. These occasional summer rainy periods may last a few days and are characterised by showers and cool temperatures around 20 °C (68 °F) in the afternoon. The annual precipitation is high and concentrated in the winter months, making Porto one of the wettest major cities of Europe. However, long periods with mild temperatures and sunny days are frequent even during the rainiest months.[citation needed]

Summers are typically sunny with average temperatures between 16 and 27 °C (61 and 81 °F), but can rise to as high as 38 °C (100 °F) during occasional heat waves. During such heat waves, the humidity remains quite low. Nearby beaches are often windy and usually cooler than the urban areas. Summer average temperatures are a few degrees cooler than those expected in more continentally Mediterranean influenced metropolises on the same latitude such as Barcelona and Florence.[citation needed]

Winter temperatures typically range between 5 °C (41 °F) during morning and 15 °C (59 °F) in the afternoon, but rarely drop below 0 °C (32 °F) at night. The weather is often rainy for long stretches, although prolonged sunny periods do occur.[citation needed]

| Climate data for Porto (Fontaínhas), elevation: 93 m or 305 ft, 1981-2010 normals , extremes 1981-2007 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.2 (73.8) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

38.7 (101.7) |

40.0 (104.0) |

40.9 (105.6) |

36.9 (98.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.8 (76.6) |

40.9 (105.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.8 (56.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.5 (49.1) |

10.4 (50.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

14.7 (58.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.3 (37.9) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 147.1 (5.79) |

110.5 (4.35) |

95.6 (3.76) |

117.6 (4.63) |

89.6 (3.53) |

39.9 (1.57) |

20.4 (0.80) |

32.9 (1.30) |

71.9 (2.83) |

158.3 (6.23) |

172.0 (6.77) |

181.0 (7.13) |

1,237 (48.7) |

| Percent possible sunshine | 40 | 42 | 52 | 55 | 55 | 61 | 66 | 68 | 63 | 54 | 46 | 44 | 54 |

| Source: IPMA[48] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Porto (Fontaínhas), elevation: 100 m or 330 ft, 1961-1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.3 (72.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

38.7 (101.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.2 (100.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

32.2 (90.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

38.7 (101.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.9 (57.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.2 (61.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.5 (58.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −3.3 (26.1) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

0.1 (32.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 171.0 (6.73) |

169.0 (6.65) |

112.0 (4.41) |

112.0 (4.41) |

89.0 (3.50) |

53.0 (2.09) |

16.0 (0.63) |

22.0 (0.87) |

64.0 (2.52) |

131.0 (5.16) |

152.0 (5.98) |

176.0 (6.93) |

1,267 (49.88) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.0 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 108 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81.0 | 80.0 | 75.0 | 74.0 | 74.0 | 74.0 | 73.0 | 73.0 | 76.0 | 80.0 | 81.0 | 81.0 | 76.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 124.0 | 129.0 | 192.0 | 217.0 | 258.0 | 274.0 | 308.0 | 295.0 | 224.0 | 184.0 | 139.0 | 124.0 | 2,468 |

| Source: NOAA[49] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Porto | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

13.8 (56.9) |

13.8 (56.9) |

15.2 (59.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.3 (63.2) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.1 (64.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

16.2 (61.1) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.3 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4.9 |

| Source: Weather Atlas [50] | |||||||||||||

Politics and government

- See also: List of mayors of Porto and Metropolitan Area of Porto

Local election results 1976-2017

| Election year | PCP | PS | PSD | CDS | UDP | APU | AD | PRD | CDU | BE | PAN | RM | Oth | Inv | Turnout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | 13.8 | 34.7 | 24.5 | 20.0 | 0.4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.1 | 2.1 | 73.4 |

| 1979 | - | 30.7 | - | - | 1.6 | 16.7 | 49.7 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.6 | 2.0 | 79.3 |

| 1982 | - | 34.5 | - | - | 0.8 | 19.5 | 42.6 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.4 | 2.2 | 73.8 |

| 1985 | - | 26.8 | 36.1 | 8.4 | 0.9 | 18.1 | - | 7.4 | - | - | - | - | 0.2 | 2.1 | 60.8 |

| 1989 | - | 41.5 | 31.8 | 10.3 | 0.4 | - | - | 0.7 | 11.5 | - | - | - | 1.4 | 2.4 | 54.5 |

| 1993 | - | 59.6 | 25.6 | 4.8 | 0.4 | - | - | - | 7.2 | - | - | - | 0.4 | 2.0 | 58.3 |

| 1997 | - | 55.8 | 26.3 | 0.7 | - | - | - | 11.3 | - | - | - | 1.5 | 4.5 | 48.1 | |

| 2001 | - | 38.5 | 42.8 | - | - | - | - | 10.5 | 2.6 | - | - | 1.3 | 4.5 | 48.3 | |

| 2005 | - | 36.1 | 46.2 | - | - | - | - | 9.0 | 4.2 | - | - | 1.4 | 3.2 | 58.5 | |

| 2009 | - | 34.7 | 47.5 | - | - | - | - | 9.8 | 5.0 | - | - | 0.7 | 2.4 | 56.8 | |

| 2013 | - | 22.7 | 21.1 | - | - | - | - | - | 7.4 | 3.6 | - | 39.3 | 1.6 | 4.4 | 52.6 |

| 2017 | - | 28.6 | 10.4 | - | - | - | - | - | 5.9 | 5.3 | 1.9 | 44.5 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 53.7 |

| Source: Comissão Nacional de Eleições | |||||||||||||||

Economy

As the most important city in the heavily industrialized northwest, many of the largest Portuguese corporations from diverse economic sectors, like Altri, Ambar, Amorim, Bial, Cerealis, BPI, CIN, EFACEC, Frulact, Lactogal, Millennium bcp, Porto Editora, Grupo RAR, Sonae, Sonae Indústria, and Unicer, are headquartered in the Greater Metropolitan Area of Porto, most notably, in the core municipalities of Maia, Matosinhos, Porto, and Vila Nova de Gaia.

The country's biggest exporter (Petrogal) has one of its two refineries near the city, in Leça da Palmeira (13 km) and the second biggest (Qimonda, now bankrupt) has its only factory also near the city in Mindelo (26 km).[51]

The city's former stock exchange (Bolsa do Porto) was transformed into the largest derivatives exchange of Portugal, and merged with Lisbon Stock Exchange to create the Bolsa de Valores de Lisboa e Porto, which eventually merged with Euronext, together with Amsterdam, Brussels, LIFFE and Paris stock and futures exchanges. The building formerly hosting the stock exchange is currently one of the city's touristic attractions, the Salão Árabe (Arab Room in English) being its major highlight.

Porto hosts a popular Portuguese newspaper, Jornal de Notícias. The building where its offices are located (which has the same name as the newspaper) was up to recently[when?] one of the tallest in the city (it has been superseded by a number of modern buildings which have been built since the 1990s).[citation needed]

Porto Editora, one of the biggest Portuguese publishers, is also in Porto. Its dictionaries are among the most popular references used in the country, and the translations are very popular as well.

The economic relations between the city of Porto and the Upper Douro River have been documented since the Middle Ages. However, they were greatly deepened in the modern ages. [citation needed] Indeed, sumach, dry fruits and nuts and the Douro olive oils sustained prosperous exchanges between the region and Porto. From the riverside quays at the river mouth, these products were exported to other markets of the Old and New World. But the greatest lever to interregional trade relations resulted from the commercial dynamics of the Port wine (Vinho do Porto) agro industry. [citation needed] It decidedly bolstered the complementary relationship between the large coastal urban centre, endowed with open doors to the sea, and a region with significant agricultural potential, especially in terms of the production of extremely high quality fortified wines, known by the world-famous label Port. The development of Porto was also closely connected with the left margin of River Douro in Vila Nova de Gaia, where is located the amphitheatre-shaped slope with the Port wine cellars.

In a study concerning competitiveness of the 18 Portuguese district capitals, Porto was the worst-ranked. The study was made by Minho University economics researchers and was published in Público newspaper on 30 September 2006. The best-ranked cities in the study were Évora, Lisbon and Coimbra.[52] Nevertheless, the validity of this study was questioned by some Porto's notable figures (such as local politicians and businesspersons) who argued that the city proper does not function independently but in conurbation with other municipalities.[53] A new ranking, published in the newspaper Expresso (Portuguese Newspaper) in 2007 which can be translated to "The Best Cities to Live in Portugal" ranked Porto in third place (tied with Évora) below Guimarães and Lisbon.[54] The two studies are not directly comparable as they use different dependent measures.

The Porto metropolitan area had a GDP amounting to $43.0 billion, and $21,674 per capita.[55]

Transport

Roads and bridges

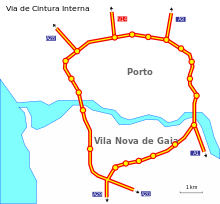

The road system capacity is augmented by the Via de Cintura Interna or A20, an internal highway connected to several motorways and city exits, complementing the Circunvalação 4-lane peripheric road, which borders the north of the city and connects the eastern side of the city to the Atlantic shore. The city is connected to Valença (Viana do Castelo) by highway A28, to Estarreja (Aveiro) by the A29, to Lisbon by the A1, to Bragança by the A4 and to Braga by the A3. There is also an outer-ring road, the A41, that connects all the main cities around Porto, linking the city to other major metropolitan highways such as the A7, A11, A42, A43 and A44. Since 2011, a new highway, the A32, connects the metropolitan area to São João da Madeira and Oliveira de Azeméis.

During the 20th century, major bridges were built: Arrábida Bridge, which at its opening had the biggest concrete supporting arch in the world, and connects north and south shores of the Douro on the west side of the city, S. João, to replace D. Maria Pia and Freixo, a highway bridge on the east side of the city. The newest bridge is Ponte do Infante, finished in 2003. Two more bridges are said to be under designing stages and due to be built in the next 10 years, one on the Campo Alegre area, nearby the Faculty of Humanities and the Arts, and another one in the area known as the Massarelos valley. [citation needed]

Porto is often referred to as Cidade das Pontes (City of the Bridges), besides its more traditional nicknames of "Cidade Invicta" (Unconquered/ Invincible City) and "Capital do Norte" (Capital of the North).

Cruising

In July 2015 a new cruise terminal was opened at the port of Leixões, which is north of the city in Matosinhos.

Airports

Porto is served by Francisco de Sá Carneiro Airport which is located in Pedras Rubras, Moreira da Maia civil parish of the neighbouring Municipality of Maia, some 15 kilometres (9 miles) to the north-west of the city centre. The airport is a state-of-the-art facility, having undergone a massive programme of refurbishment due to the Euro 2004 football championships being partly hosted in the city.

Public transport

Railways

Porto's main railway station is Campanhã railway station, located in the eastern part of the city and connected to the lines of Douro (Peso da Régua/Tua/Pocinho), Minho (Barcelos/Viana do Castelo/Valença) and centre of Portugal (on the main line to Aveiro, Coimbra and Lisbon).

From Campanhã station, both light rail and suburban rail services connect to the city center. The main central station is São Bento Station, which is itself a notable landmark located in the heart of Porto.

Porto is well connected with Lisbon with high-speed trains called Alpha Pendular, that cover the distance in 2h 42min. The intercities take slightly more than 3 hours to cover the same distance.

In addition, Porto is connected to the Spanish city of Vigo with the Celta train, running twice every day. The journey takes 2 hours and 20 minutes to connect both cities. [56]

Light rail

Currently the major project is the Porto Metro, a light rail system. Consequently, the Infante bridge was built for urban traffic, replacing the Dom Luís I, which was dedicated to the light rail on the second and higher of the bridge's two levels. Six lines are open: lines A (blue), B (red), C (green) and E (purple) all begin at Estádio do Dragão (home to FC Porto) and terminate at Senhor de Matosinhos, Póvoa de Varzim (via Vila do Conde), ISMAI (via Maia) and Francisco Sá Carneiro airport respectively. Line D (yellow) currently runs from Hospital S. João in the north to Santo Ovídio on the southern side of the Douro river. Line F (orange), from Senhora da Hora (Matosinhos) to Fânzeres (Gondomar). The lines intersect at the central Trindade station. Currently the whole network spans 60 km (37 mi) using 68 stations, thus being the biggest rapid transit system in the country.

| Line | Length (km) |

Stations | Inauguration | Vehicle | |

| 15,6 | 23 | 7 December 2002 | Flexity Outlook (Eurotram) | ||

| 33,6 | 35 | 13 March 2005 | Flexity Swift (Tram-train) | ||

| 19,6 | 24 | 30 July 2005 | Flexity Swift (Tram-train) | ||

| 9,2 | 16 | 18 September 2005 | Flexity Outlook (Eurotram) | ||

| 16,7 | 21 | 27 May 2006 | Flexity Outlook (Eurotram) | ||

| 17,4 | 24 | 2 January 2011 | Flexity Outlook (Eurotram) | ||

| 0,3 | 2 | 19 February 2004 | Funicular of Guindais | ||

Buses

The city has an extensive bus network run by the STCP (Sociedade dos Transportes Colectivos do Porto, or Porto Public Transport Society) which also operates lines in the neighbouring cities of Gaia, Maia, Matosinhos, Gondomar and Valongo. Other smaller companies connect such towns as Paços de Ferreira and Santo Tirso to the town center. In the past the city also had trolleybuses.[57] A bus journey is 1.85 Euro, which must be paid in cash.

Trams

A tram (streetcar) network, of which only three lines remain one of them being a tourist line on the shores of the Douro, saw its construction begin on 12 September 1895, therefore being the first in the Iberian Peninsula. The lines in operation all use vintage tramcars, so the service has become a heritage tramway. STCP also operates these routes as well as a tram museum. The first line of the area's modern-tram, or light rail system, named Metro do Porto, opened for revenue service in January 2003[58] (after a brief period of free, introductory service in December 2002).

Porto public transportation statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Porto, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 47 minutes. About 6.5% of public transit riders ride for more than two hours every day. The average time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 12 minutes, while 17.4% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people ride in a single trip with public transit is 6 km, while 5% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[59]

Culture

In 2001, Porto shared the designation European Culture Capital.[60] In the scope of these events, the construction of the major concert hall space Casa da Música, designed by the Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas, was initiated and finished in 2005.

The first Portuguese moving pictures were taken in Porto by Aurélio da Paz dos Reis and shown there on 12 November 1896 in Teatro do Príncipe Real do Porto, less than a year after the first public presentation by Auguste and Louis Lumière. The country's first movie studios Invicta Filmes was also erected in Porto in 1917 and was open from 1918 to 1927 in the area of Carvalhido. Manoel de Oliveira, a Portuguese film director and the oldest director in the world to be active until his death in 2015, is from Porto. Fantasporto is an international film festival organized in Porto every year.

Many renowned Portuguese music artists and cult bands such as GNR, Rui Veloso, Sérgio Godinho, Clã, Pluto, Azeitonas and Ornatos Violeta are from the city or its metropolitan area. Porto has several museums, concert halls, theaters, cinemas, art galleries, libraries and bookshops. The best-known museums of Porto are the National Museum Soares dos Reis (Museu Nacional de Soares dos Reis), which is dedicated especially to the Portuguese artistic movements from the 16th to the 20th century, and the Museum of Contemporary Art of the Serralves Foundation (Museu de Arte Contemporânea).

The city has concert halls of a rare beauty and elegance such as the Coliseu do Porto by the Portuguese architect Cassiano Branco; an exquisite example of the Portuguese decorative arts. Other notable venues include the historical São João National Theatre, the Rivoli theatre, the Batalha cinema and Casa da Música, inaugurated in 2005.[61] The city has the Lello Bookshop, which is frequently rated among the top bookstores in the world.[62]

Porto houses the largest synagogue in the Iberian Peninsula and one of the largest in Europe – Kadoorie Synagogue, inaugurated in 1938.

Entertainment

Porto's most popular event is St. John (São João Festival) on the night of 23–24 June.[63] In this season it's a tradition to have a vase with bush basil decorated with a small poem. During the dinner of the great day people usually eat sardines and boiled potatoes together with red wine.

Another major event is Queima das Fitas, that starts in the first Sunday of May and ends in the second Sunday of the month. Basically, before the beginning of the study period preceding the school year’s last exams, academia tries to have as much fun as possible. The week has 12 major events, starting with the Monumental Serenata on Sunday, and reaching its peak with the Cortejo Académico on Tuesday, when about 50,000 students of the city's higher education institutions march through the downtown streets till they reach the city hall. During every night of the week a series of concerts takes place on the Queimódromo, next to the city’s park, where it’s also a tradition for the students in their second-to-last year to erect small tents where alcohol is sold in order to finance the trip that takes place during the last year of their course of study; an average of 50,000 students attend these shows.[64]

Porto was considered the fourth best value destination for 2012, by Lonely Planet.

Arts

In 2005, the municipality funded a public sculpture to be built in the Waterfront Plaza of Matosinhos. The resulting sculpture is entitled She Changes[65] by American artist, Janet Echelman, and spans the height of 50 × 150 × 150 metres.

Architecture

Due to its long history, the city of Porto carries an immense architectural patrimony. From the Romanesque Cathedral to the Social Housing projects developed through the late 20th century, much could be said surrounding architecture.

Porto is home to the Porto School of Architecture, one of the most prestigious architecture schools in Europe and the world. It is also home to two earners of the Pritzker Architecture Prize (two former students of the aforementioned school): Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura.

Gastronomy

Porto is home to a number of dishes from traditional Portuguese cuisine. A typical dish from this city is Tripas à Moda do Porto (Tripes Porto style). Bacalhau à Gomes de Sá (Gomes de Sá Bacalhau) is another typical codfish dish born in Porto and popular in Portugal.

The Francesinha – literally Frenchy, or more accurately little French (female) – is the most famous popular native snack food in Porto. It is a kind of sandwich with several meats covered with cheese and a special sauce made with beer and other ingredients.

Port wine, an internationally renowned wine, is widely accepted as the city's dessert wine, especially as the wine is made along the Douro River which runs through the city.

Tourism

Over the last years, Porto has experienced significant tourism increases which may be linked to the Ryanair hub at Francisco de Sá Carneiro Airport. Porto won the European Best Destination 2012, 2014 and 2017 awards.[18]

Education

The city has a large number of public and private elementary and secondary schools, as well as kindergartens and nurseries. Due to the depopulation of the city's interior, however, the number of students has dropped substantially in the last decade, forcing a closure of some institutions. [citation needed] The oldest and largest international school located in Porto is the Oporto British School, established in 1894. There are more international schools in the city, such as the French School[66] and the Deutsch School[67], both created in the 20th century.

University

Porto has several institutions of higher education, the largest one being the state-managed University of Porto (Universidade do Porto), which is the second largest Portuguese university, after the University of Lisbon, with approximately 28,000 students and considered one of the 100 best Universities in Europe.[68] There is also a state-managed polytechnic institute, the Instituto Politécnico do Porto (a group of technical colleges), and private institutions like the Lusíada University of Porto, Universidade Fernando Pessoa (UFP), the Porto's Higher Education School of Arts (ESAP- Escola Superior Artística do Porto) and a Vatican state university, the Portuguese Catholic University in Porto (Universidade Católica Portuguesa – Porto) and the Portucalense University in Porto (Universidade Portucalense – Infante D. Henrique). Due to the recognition, potential for employment and higher revenue, there are many students from the entire country, particularly from the north of Portugal, attending a college or university in Porto.

For foreigners wishing to study Portuguese in the city there are a number of options. As the most popular city in Portugal for ERASMUS students, most universities have facilities to assist foreigners in learning the language. There are also several private learning institutions in the city.

Public health

Porto district has the highest rate of tuberculosis positive cases in Portugal. Porto tuberculosis rates are at Third World proportions (comparatively, London faces a similar phenomenon).[69] The incidence of positive cases was 23/100 000 nationwide in 1994, with a rate of 24/100 000 in Lisbon and 37/100 000 in Porto. Porto area represented the worst epidemiological situation in the country, with very high rates in some city boroughs and in some poor fishing and declining industrial communities. Epidemiological analysis indicated the existence of undisclosed sources of infection in these communities, responsible for continuing transmission despite a control rate of 83% in the district.[70] In 2002, the situation was not better with 34/100 000 nationwide and 64/100 000 in Porto district. In 2004 the situation improved to 53/100 000.[71]

Sport

Porto, in addition to football, is the home to many athletic sports arenas, most notably the city-owned Pavilhão Rosa Mota, swimming pools in the area of Constituição (between the Marquês and Boavista), and other minor arenas, such as the Pavilhão do Académico.

Porto is home to northern Portugal's only cricket club, the Oporto Cricket and Lawn Tennis Club. Annually, for more than 100 years, a match (the Kendall Cup) has been played between the Oporto Club and the Casuals Club of Lisbon, in addition to regular games against touring teams (mainly from England). The club's pitch is located off the Rua Campo Alegre.

In 1958 and 1960, Porto's streets hosted the Formula One Portuguese Grand Prix on the Boavista street circuit, which are reenacted annually, in addition to a World Touring Car Championship race.

Every year in October the Porto Marathon is held through the streets of the old city of Porto.

Football

As in most Portuguese cities, football is the most important sport. There are two main teams in Porto: FC Porto in the parish of Campanhã, in the eastern part of the city and Boavista in the area of Boavista in the parish of Ramalde, in the western part of the city, close to the city centre. FC Porto is one of the "Big Three" teams in the Portuguese league, and was European champion in 1987 and 2004, won the UEFA Cup (2003) and Europa League (2011) and the Intercontinental Toyota Cup in 1987 and 2004. Boavista have won the championship once, in the 2000–01 season and reached the semi-finals of the UEFA Cup in 2003, where they lost 2–1 to Celtic.

Formerly, Salgueiros from Paranhos was a regular first division club during the 1980s and 1990s but, due to financial indebtedness, the club folded in the 2000s. The club was refounded in 2008 and began playing at the regional level. They now play at the third level of Portugal's national football pyramid. However, the new Salgueiros club plays outside the city in Pedrouços, Maia.

The biggest stadiums in the city are FC Porto's Estádio do Dragão and Boavista's Estádio do Bessa. The first team in Porto to own a stadium was Académico, who played in the Estádio do Lima, Académico was one of the eight teams to dispute the first division. Salgueiros, who sold the grounds of Estádio Engenheiro Vidal Pinheiro field to the Porto Metro and planned on building a new field in the Arca d'Água area of Porto. Located a few hundred metres away from the old grounds, it became impossible to build on this land due to a large underground water pocket, and, consequently, they moved to the Estádio do Mar in Matosinhos (owned by Leixões). For the Euro 2004 football competition, held in Portugal, the Estádio do Dragão was built (replacing the old Estádio das Antas) and the Estádio do Bessa was renovated.

Basketball

The FC Porto (basketball) team plays its home games at the Dragão Caixa. Its squad won the second most championships in the history of Portugal's 1st Division. Traditionally, the club provides the Portuguese national basketball team with numerous key players.[72]

International relations

Twin towns — sister cities

Liège, Belgium, since 1977

Liège, Belgium, since 1977 Bordeaux, France, since 1978[74][75]

Bordeaux, France, since 1978[74][75] Bristol, England, UK, since 1984[76]

Bristol, England, UK, since 1984[76] Vigo, Galicia, Spain, since 1986

Vigo, Galicia, Spain, since 1986 Nagasaki, Japan, since 1978[77]

Nagasaki, Japan, since 1978[77] Crotone, Italy, since 2010[78]

Crotone, Italy, since 2010[78] Jena, Germany, since 1984

Jena, Germany, since 1984 Macau, China, since 1997

Macau, China, since 1997 Duruelo de la Sierra, Castile and León, Spain, since 1989

Duruelo de la Sierra, Castile and León, Spain, since 1989 Bangkok, Thailand, since 2016[79]

Bangkok, Thailand, since 2016[79] Brno, Czech Republic, since 2004

Brno, Czech Republic, since 2004 Shanghai, China, since 1995

Shanghai, China, since 1995 Beira, Mozambique, since 1989

Beira, Mozambique, since 1989 Recife, Brazil, since 1981

Recife, Brazil, since 1981 Luanda, Angola, since 1989

Luanda, Angola, since 1989 Neves, São Tomé and Príncipe, since 1987

Neves, São Tomé and Príncipe, since 1987 Ndola, Zambia, since 1978

Ndola, Zambia, since 1978 Canchungo, Guiné Bissau, since 2001

Canchungo, Guiné Bissau, since 2001 Klaipėda, Lithuania, since 2007

Klaipėda, Lithuania, since 2007 Mindelo, Cape Verde, since 1992

Mindelo, Cape Verde, since 1992 León, Castile and León, Spain, since 2001

León, Castile and León, Spain, since 2001 Marsala, Italy, since 2016[80]

Marsala, Italy, since 2016[80]

Notable citizens

- Alexandre Quintanilha (born 9 August 1945) – scientist and Member of Parliament

- Almeida Garrett (1799–1854) – notable writer, theater director and liberalist

- Álvaro Siza Vieira (born 25 June 1933) – architect

- André Villas-Boas (born 17 October 1977) – football manager

- António Nobre (António Pereira Nobre, 16 August 1867 – 18 March 1900) – poet, died of tuberculosis in Foz do Douro, Porto, in 1900, after trying to recover in a number of places. His masterpiece Só (Paris, 1892), was the only book he published

- António Pinho Vargas (born 15 August 1951) – composer

- António da Silva Porto (Francisco Ferreira da Silva Porto, 24 August 1817 – 1890) – Portuguese trader and explorer in Angola, in the Portuguese West Africa. The town of Kuito, founded by the Portuguese and named Belmonte at that time, was renamed Silva Porto

- António Soares dos Reis (1847–1889) – sculptor

- Armando de Basto (1889–1923) – painter

- Artur Loureiro (1853–1932) – painter

- Brás Cubas (1507–1589) – Portuguese explorer, colonial administrator and founder of Santos in Brazil

- Bruno Alves (born 27 November 1981) – footballer

- Charles Albert of Sardinia (1798–1849) – Italian monarch

- Diogo Vasconcelos (1968–2011) – politician and social innovator

- Duarte Coelho Pereira (c. 1485–1554) – Portuguese nobleman, military leader, colonial administrator and founder of Olinda in Brazil

- Duda (born 27 June 1980) – footballer

- Eduardo Souto de Moura (born 25 July 1952) – architect

- Estevão Gomes, also known as Esteban Gómez and Estevan Gómez, (c. 1483–1538) – cartographer and explorer. He sailed at the service of Spain in the fleet of Ferdinand Magellan, but deserted the expedition before reaching the Strait of Magellan, and returned to Spain in May 1521. In 1524 he explored present-day Nova Scotia sailing South along the Maine coast. He entered New York Harbor, saw the Hudson River, and eventually reached Florida in August 1525. Because of his expedition, the 1529 Diogo Ribeiro world map outlines the East coast of North America almost perfectly.

- Fernão de Magalhães (Ferdinand Magellan) (c. 1480–1521) – the globe circumnavigation navigator; probably born in Porto, but surely lived and studied in this town.

- Francisco Laranjo (born 5 June 1955) – painter

- Francisco Sá Carneiro (1934–1980) – former Prime Minister

- Francisco Vieira de Matos (1765–1805) – painter (a.k.a. Vieira Portuense)

- Freitas-Magalhães (born 1966) – psychologist and scientist

- Guilhermina Suggia (1885–1950) – cellist; born at Porto

- Henrique Hilário (born 21 October 1975) – Chelsea Football Club goalkeeper; born in Porto

- Jorge Nuno Pinto da Costa (born 28 December 1937) – president of FC Porto

- José Pacheco Pereira (born 6 January 1949) – politician, professor and political analyst

- Júlio Dinis (1839–1871) – doctor and writer

- J. K. Rowling – author of Harry Potter books

- Kaúlza de Arriaga (1915–2004) – general of the Portuguese Army

- Manoel de Oliveira (11 December 1908 – 2 April 2015) – film director

- Mary of the Divine Heart – countess Droste zu Vischering and Mother Superior of the Good Shepherd Sisters Convent

- Miguel Sousa Tavares (born 25 June 1952) – writer

- Pedro Abrunhosa (born 20 December 1960) – singer-songwriter

- Pedro de Escobar (c. 1465–after 1535) – Renaissance composer

- Pêro Vaz de Caminha (1450–1500) – wrote the letter Carta do Achamento do Brasil, announcing the discovery of Brazil

- Prince Henry the Navigator (1394–1460) – responsible for the early development of European exploration and maritime trade with other continents

- Ramalho Ortigão (1836–1912) – writer

- Raul Meireles (born 17 March 1983) – footballer

- Richard Zimler (born 1956) – novelist

- Rosa Mota (born 29 June 1958) – marathon runner, Olympic gold medalist (Seoul 1988)

- Rui Reininho (born 28 February 1955) – singer

- Sara Sampaio 1991 – supermodel

- Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen (1919–2004) – writer

- Tiago Monteiro (born 24 July 1976) – racing driver

Notes

- ^ Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpoɾtu]

- ^ /əˈpɔːrtoʊ, oʊˈpɔːrtuː/, also UK: /ɒˈpɔːrtoʊ/,[3][4] US: /oʊˈpɔːrtoʊ/),[5][6]

References

- ^ "Portugal International Dialing Code". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ IGP, ed. (2010), Carta Administrativa Oficial de Portugal (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: Instituto Geográfico Português, archived from the original on 3 July 2014, retrieved 1 July 2011

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Porto". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Oporto" (US) and "Oporto". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Oporto". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Oporto". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "Porto". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ "The 7 cheapest European cities to live in". Business Insider UK. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- ^ ITDS, Rui Campos, Pedro Senos. "Statistics Portugal". Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Demographia: World Urban Areas, March 2010

- ^ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, World Urbanization Prospects (2009 revision), (United Nations, 2010), Table A.12. Data for 2007. Archived 31 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ European Spatial Planning Observation Network, Study on Urban Functions (Project 1.4.3), Final Report, Chapter 3, (ESPON, 2007) Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thomas Brinkoff, Principal Agglomerations of the World, Retrieved 12 March 2009. Data for 1 January 2009.

- ^ "The World According to GaWC 2018". Globalization and World Cities Research Network. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "port". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Port Wine". Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Europe's best destinations 2014 – Europe's Best Destinations". europeanbestdestinations.org.

- ^ a b c "Historic Centre of Oporto". World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Semënova-Head, Larisa; Head, Brian F. "Vestígios da presença sueva no noroeste da península ibérica: na etnologia, na arqueologia e na língua". Revista Diacrítica. 27 (2): 257–277. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ Collins, Roger (1989). The Arab Conquest of Spain 710–797. Oxford, UK / Cambridge, USA: Blackwell. pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-631-19405-3.

- ^ Ribeiro, Ângelo; Hermano, José (2004), História de Portugal I — A Formação do Território [History of Portugal: The Formation of the Territory] (in Portuguese), QuidNovi, ISBN 989-554-106-6

- ^ "Treaty of Windsor – British-Portugal". britannica.com.

- ^ "Tratado de paz, amizade e confederação entre D. João I e Eduardo II, rei de Inglaterra, denominado Tratado de Windsor" (in Portuguese). Portuguese National Archives Digital Collection. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Winslett, Matthew (2008). The Nadir of Alliance: The British Ultimatum of 1890 and Its Place in Anglo-Portuguese Relations, 1147—1945. ProQuest. p. 3. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "The Mariners' Museum – EXPLORATION through the AGES". marinersmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Merson, John (1990). The Genius That Was China: East and West in the Making of the Modern World. Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. p. 72. ISBN 0-87951-397-7A companion to the PBS Series The Genius That Was China

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Francis, A.D. John Methuen and the Anglo-Portuguese Treaties of 1703. The Historical Journal Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 103 – 124.

- ^ Smith

- ^ Glover

- ^ Glover, Michael (1974). The Peninsular War 1807 – 1814, A Concise Military History. Penguin Books. pp. 96–97 description of the retreat of Soult along the Valongo and Amaranthe road. ISBN 9780141390413.

- ^ CasaHistória website, "Independence and Empire" Archived 6 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 12 June 2007

- ^ Rocha, António Silva Lopes (1829). Unjust Proclamation of His Serene Highness The Infante Don Miguel as King of Portugal or Analysis and Juridical Refutation of the Act Passed by the Denominated Three States of the Kingdom of Portugal on the 11th of July, 1828; Dedicated to the Most High and Powerful, Dona Maria II. Queen Regnant of Portugal. London, England: R. Greenlaw.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 1158. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ O desastre da ponte das barcas Jornal de Notícias, 29 March 2009 Template:Pt icon

- ^ Loyrette 1985, p.60

- ^ Manuel de Azeredo (December 1999), The Bridges of Porto – Technical Data, Faculty of Engineering, University of Porto, retrieved 12 August 2014

- ^ Costa, Patrícia (2005). "Ponte de D. Luís (IPA no. 00005548)". SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico (Information System for Architectural Heritage) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 22 September 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ "1ª Republica – Dossier temático dirigido às Escolas" (PDF). Rede Municipal de Bibliotecas Públicas do concelho de Palmela. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "5 de Outubro de 1910: a trajectória do republicanismo". In-Devir. 30 August 2010. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ A este propósito ver Quental, Antero de (1982). Prosas sócio-políticas ;publicadas e apresentadas por Joel Serrão (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda. p. 248. citado na secção "O Partido Republicano Português" deste artigo.

- ^ Diário da Junta Governativa do Reino de Portugal. Colecção Completa, nº 1 (19 Jan 1919) – nº 16 (13 Fev 1919), Porto, J. Pereira da Silva, 1919.

- Felix Correia, A Jornada de Monsanto – Um Holocausto Tragico, Lisboa, Tip. Soares & Guedes, Abril de 1919.

- ^ Luís de Magalhães, "Porque restaurámos a Carta em 1919", Correio da Manhã, 27 e 28 de Fevereiro de 1924.

- ^ "Porto UNESCO Classification". Archived from the original on 11 March 2008. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A Porto University document/study in Portuguese" (PDF). (478 KB)

- ^ "Law nr. 11-A/2013, pages 552 99–100" (PDF). Diário da República (in Portuguese). Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ^ Monge-Barrio, Aurora; Gutiérrez, Ana Sánchez-Ostiz (9 February 2018). Passive Energy Strategies for Mediterranean Residential Buildings: Facing the Challenges of Climate Change and Vulnerable Populations. Springer. ISBN 9783319698830.

- ^ "Normais Climatológicas – 1981–2010(provisórias) – Porto" (in Portuguese). Instituto de Meteorologia. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "Porto (08546) - WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ "Porto, Portugal - Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ "Petrogal domina exportações". Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Publico.pt – Índice de competitividade coloca Évora no topo e Porto em último Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine Pedro Ribeiro – 30 September 2006

- ^ Coentrão, Abel Quanto vale o Grande Porto? Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine — Publico.pt

- ^ "Expresso – Ranking of "Best Cities to Live in Portugal" where Porto was ranked in third, below Lisbon and Guimarães and tied with Évora" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (66.5 KB) - ^ "Global Metro Monitor GDP 2014". Brookings Institution.

- ^ "Train Porto - Vigo".

- ^ "Luso Pages - Oporto / Porto (Portugal) Trams and Trolleybuses". Altrinchamfc.co.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ "Porto Light Rail Project, Portugal". Railway Technology. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Porto Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ AtlasWeb (2011). "Rotterdam and Porto: Cultural Capitals 2001: visitor research. – ATLAS Shop". atlas-webshop.org. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ^ Nicolai Ouroussoff, "A Vision of a Mobile Society Rolls Off the Assembly Line", New York Times, 25 December 2005

- ^ "Top shelves". The Guardian. 11 January 2008. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "São João Festival (St John Festival)". World Events Guide. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "Federação Académica do Porto". Fap.pt. Retrieved 6 May 2009. You can check http://www.f8life.com for entertainment events in Porto.

- ^ Janet Echelman's She Changes Sculpture Magazine July–August 2005

- ^ "Lycée Français International de Porto". LFIP.

- ^ "1901-1921". Dsporto.de.

- ^ Ranking Web of World Universities Archived 18 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "London tuberculosis rates now at Third World proportions". PR Newswire. 6 December 2002. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

- ^ "View Article". Eurosurveillance. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ publico.pt Archived 11 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Portugal|2015 EuroBasket, ARCHIVE.FIBA.COM. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ^ "Geminações de Cidades e Vilas" (in Portuguese). Associação Nacional de Municípios Portugueses. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Bordeaux – Rayonnement européen et mondial". Mairie de Bordeaux (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Bordeaux-Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Bristol City – Town twinning". Bristol City Council. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Sister Cities of Nagasaki City". International Affairs Section, Nagasaki City Hall. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ www.ideafutura.com, Idea Futura srl -. "Comune di Crotone – Crotone ed Oporto". comune.crotone.it.

- ^ The Municipality of Porto; Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (5 August 2016). "Memorandum of understanding between The Municipality of Porto Portuguese Republic and The Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Kingdom of Thailand".

- ^ Marchetti, Claudia (13 May 2016). "Marsala e Porto stringono un gemellaggio: "Insieme per la cultura"". Itacanotizie.it. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

Bibliography

- Francis, A.D. John Methuen and the Anglo-Portuguese Treaties of 1703. The Historical Journal Vol. 3, No. 2

- Glover, Michael, The Peninsular War 1807–1814 Penguin, 1974.

- John Lomas, ed. (1889), "Porto", O'Shea's Guide to Spain and Portugal (8th ed.), Edinburgh: Adam & Charles Black

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Loyrette, Henri. Gustave Eiffel. New York: Rizzoli, 1985 ISBN 0 8478 0631 6

- "Porto", A Handbook for Travellers in Portugal (2nd ed.), London: John Murray, 1856, OCLC 34745440, retrieved 10 February 2016

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Redacção Quidnovi, com coordenação de José Hermano Saraiva, História de Portugal, Dicionário de Personalidades, Volume VIII, Ed. QN-Edição e Conteúdos, S.A., 2004

- Smith, Digby, The Napoleonic Wars Data Book Greenhill, 1998.

External links

- Coordination and Development Committee of the North Region

- Metropolitan Area of Porto

- Tourism of Porto and Norte Region, Portugal