American Civil War

- "The Civil War" is the most common term in the United States of America for this conflict; see Naming the American Civil War.

| American Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

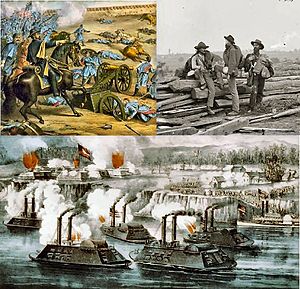

(clockwise from upper right) Confederate prisoners at Gettysburg; Battle of Fort Hindman, Arkansas; Rosecrans at Stones River, Tennessee | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant |

Jefferson Davis, Robert Edward Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,200,000 | 1,064,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

110,000 killed in action, 360,000 total dead, 275,200 wounded |

93,000 killed in action, 258,000 total dead 137,000+ wounded | ||||||

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was a sectional conflict in the United States of America between the federal government (the "Union") and eleven Southern slave states that declared their secession and formed the Confederate States of America, led by President Jefferson Davis. The Union, led by President Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party, opposed the expansion of slavery and rejected any right of secession. Fighting commenced on April 12, 1861 when Confederate forces attacked a federal military installation at Fort Sumter, South Carolina.

During the first year, the Union asserted control of the border states and established a naval blockade as both sides raised large armies. In 1862 the large, bloody battles began. After the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation made the freeing of the slaves a war goal, despite opposition from Copperheads who supported slavery and secession. Emancipation ensured that Britain and France would not intervene to help the Confederacy. In addition, the goal also allowed the Union to recruit African-Americans for reinforcements, a resource that the Confederacy did not dare exploit until it was too late. War Democrats reluctantly accepted emancipation as part of total war needed to save the Union. In the East, Robert Edward Lee rolled up a series of Confederate victories over the Army of the Potomac, but his best general, Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, was killed at the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. Lee's invasion of the North was repulsed at the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania in July 1863; he barely managed to escape back to Virginia. In the West, the Union Navy captured the port of New Orleans in 1862, and Ulysses S. Grant seized control of the Mississippi River by capturing Vicksburg, Mississippi in July 1863, thus splitting the Confederacy.

By 1864, long-term Union advantages in geography, manpower, industry, finance, political organization and transportation were overwhelming the Confederacy. Grant fought a number of bloody battles with Lee in Virginia in the summer of 1864. Lee won in a tactical sense but lost strategically, as he could not replace his casualties and was forced to retreat into trenches around his capital, Richmond, Virginia. Meanwhile, William Tecumseh Sherman captured Atlanta, Georgia. Sherman's March to the Sea destroyed a hundred-mile-wide swath of Georgia. In 1865, the Confederacy collapsed after Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House and the slaves were freed.

The full restoration of the Union was the work of a highly contentious postwar era known as Reconstruction. The war produced about 970,000 casualties (3% of the population), including approximately 620,000 soldier deaths - two-thirds by disease. [1] The causes of the war, the reasons for its outcome, and even the name of the war itself are subjects of lingering controversy even today. The main results of the war were the restoration and strengthening of the Union, and the end of slavery in the United States.

Causes of the War

- Main articles: Origins of the American Civil War, Timeline of events

Secession was caused by the coexistence of a slave-owning South and an increasingly anti-slavery North. Lincoln did not propose federal laws making slavery unlawful where it already existed, but he had, in his 1858 House Divided Speech, envisioned it as being set on "the course of ultimate extinction". Much of the political battle in the 1850s focused on the expansion of slavery into the newly created territories. Both North and South assumed that if slavery could not expand it would wither and die.

Well-founded Southern fears of losing control of the Federal government to antislavery forces, and northern fears that the slave power already controlled the government, brought the crisis to a head in the late 1850s. Sectional disagreements over the morality of slavery, the scope of democracy and the economic merits of free labor vs. slave plantations caused the Whig and "Know-Nothing" parties to collapse, and new ones to arise (the Free Soil Party in 1848, the Republicans in 1854, Constitutional Union in 1860). In 1860, the last remaining national political party, the Democratic Party, split along sectional lines.

Other factors include states' rights, economics, and modernization.

Slavery and antislavery

The root problem was the institution of slavery, which had been introduced into colonial North America in 1619. The Compromise of 1850 included a new, stronger fugitive slave law that required federal agents to capture and return slaves that escaped into northern free states. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 overthrew the Compromise of 1820 and led to the new antislavery Republican Party. The Compromise of 1820, which had been confirmed in 1850, had outlawed slavery so far in the territories north and west of Missouri.[2]

The Supreme Court decision of 1857 in Dred Scott v. Sandford added to the controversy. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's decision said that slaves "have no rights which any white man is bound to respect",[3] and that slaves could be taken to free states and territories. Lincoln warned that "the next Dred Scott decision"[4] could threaten northern states with slavery.

Since fewer than 800 of the almost 4 million[5] slaves escaped in 1860, the fugitive slave controversy was not a practical reason for secession. (More had escaped in previous years; see Underground Railroad.) The number that escaped was offset by free Northern blacks who were kidnapped as slaves. And secession only did away with enforcement of the fugitive slave law altogether. Kansas had only two slaves in 1860 because the territories had the wrong soil and climate for labor-intensive forms of agriculture.[6] Allan Nevins summarizes this argument by concluding that "Both sides were equally guilty of hysteria."[7]

There was a strong correlation between the number of plantations in a region and the degree of support for secession. The states of the deep south had the greatest concentration of plantations and were the first to secede. The upper South slave states of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee had fewer plantations and rejected secession until the Fort Sumter crisis forced them to choose sides. Border states had fewer plantations still and never seceded.[8]

Rejection of compromise

Until December 20, 1860, the political system had always successfully handled inter-regional crises. All but one crisis involved slavery, starting with debates on the three-fifths clause in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Congress had solved the crisis over the admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1819-21, the controversy over South Carolina's nullification of the tariff in 1832, the acquisition of Texas in 1845, and the status of slavery in the territory acquired from Mexico in 1850.[9]

However, in 1854, the old Second Party System broke down after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Whig Party disappeared, and the new Republican Party arose in its place. It was the nation's first major party with only sectional appeal and a commitment to stop the expansion of slavery.

One Republican leader, Senator Charles Sumner, was violently attacked and nearly killed at his desk in the Senate by Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina. Brooks attacked Sumner with a gold-knobbed gutta-percha cane, which his Southern admirers replaced with similar canes with inscriptions like "Hit him again."[10]

Open warfare in the Kansas Territory ("Bleeding Kansas"), the Dred Scott decision of 1857, John Brown's raid in 1859 and the split in the Democratic Party in 1860 polarized the nation between North and South. The election of Lincoln in 1860 was the final trigger for secession. During the secession crisis, many sought compromise—of these attempts, the best known was the "Crittenden Compromise"—but all failed.

A deeper reason for the rejection of compromise was the fear that conspiracies threatened to destroy the republic. By the 1850s, two loomed most threatening: the South feared the supposedly abolitionist Republican Party (the "Black Republicans"); Republicans in the North feared what they called the Slave Power.[11]

Abolitionism

The Second Great Awakening of the 1820s and 1830s in religion inspired reform movements, one of the most notable of which was the abolitionists; these were later supported by Transcendentalism. Unfortunately, "abolitionist" had several meanings at the time, and still retains some ambiguity. The followers of William Lloyd Garrison, like Wendell Phillips, or Frederick Douglass demanded the "immediate abolition of slavery", hence the name. Others, like Theodore Weld and Arthur Tappan wanted immediate action, but that action might well be a program of gradual emancipation, with a long intermediate stage. "Antislavery men", like John Quincy Adams, did what they could to limit slavery and end it where possible. In the last years before the war, "antislavery" could mean the Northern majority, like Abraham Lincoln, who opposed expansion of slavery or its influence, as by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, or the Fugitive Slave Act. Many Southerners called all these abolitionists, without distinguishing them from the Garrisonians. James McPherson explains the abolitionists' deep beliefs: "All people were equal in God's sight; the souls of black folks were as valuable as those of whites; for one of God's children to enslave another was a violation of the Higher Law, even if it was sanctioned by the Constitution."[12]

Slaveowners were angry over the attacks on their "peculiar institution" of slavery. Starting in the 1830s, there was a vehement and growing ideological defense of slavery.[13] Slaveowners claimed that slavery was a positive good for masters and slaves alike, and that it was explicitly sanctioned by God. Biblical arguments were made in defense of slavery by religious leaders such as the Rev. Fred A. Ross and political leaders such as Jefferson Davis.[14]

Beginning in the 1830s, the U.S. Postmaster General refused to allow the mails to carry abolition pamphlets to the South.[15] Northern teachers suspected of any tinge of abolitionism were expelled from the South, and abolitionist literature was banned. Southerners rejected the denials of Republicans that they were abolitionists, and pointed to John Brown's attempt in 1859 to start a slave uprising as proof that multiple Northern conspiracies were afoot to ignite bloody slave rebellions. Although some abolitionists did call for slave revolts, no evidence of any other actual Brown-like conspiracy has been discovered.[16] The North felt threatened as well, for as Eric Foner concludes, "Northerners came to view slavery as the very antithesis of the good society, as well as a threat to their own fundamental values and interests".[17]

Uncle Tom's Cabin

The most famous antislavery novel was Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Inspired by the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 which made the escape narrative part of everyday news, Stowe emphasized the horrors that abolitionists had long claimed about slavery. Her depiction of the evil slaveowner Simon Legree, a transplanted Yankee who kills the Christ-like Uncle Tom, outraged slaveowners.[18] Stowe made Simon Legree a transplanted Yankee to show that she was attacking not the southern people but slavery as an institution. She published a Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin to prove that, even though the book was fiction, many events in the book were based on fact.[19][20] According to Stowe's son, when President Lincoln met her in 1862, he commented, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war!"[21]

John Brown

John Brown has been called "the most controversial of all nineteenth-century Americans."[22] His attempt to start a slave rebellion in 1859 electrified the nation. Uniquely among the Garrisonians, he resorted to violence. Most historians depict Brown as a bloodthirsty zealot and madman who briefly stepped into history but did little to influence it. Some scholars, however, glorify Brown, giving him credit for starting the Civil War and arguing "it is misleading to identify Brown with modern terrorists."[23]

John Brown started his fight against slavery in Kansas in 1856, during the Bleeding Kansas crisis. Border Ruffians used bowie knives and vote fraud to establish a pro-slavery government at Lecompton. There was Border Ruffian violence in Lawrence, Kansas in 1855 and 1856 (see Sacking of Lawrence). And Border Ruffians kidnapped and killed six Free-State men. So Brown and his band killed five pro-slavery people at Pottawatomie Creek, Kansas.

His famous raid in October, 1859, involved a band of 22 men who seized the federal arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, knowing it contained tens of thousands of weapons. Brown, like his Boston supporters, believed that the South was on the verge of a gigantic slave uprising and that one spark would set it off. Brown's raid, says historian David Potter, "was meant to be of vast magnitude and to produce a revolutionary slave uprising throughout the South." The raid was a fiasco. Not a single slave revolted. Instead, Brown was quickly captured, tried for treason (against the state of Virginia) and hanged. At his trial, Brown exuded a remarkable strength of character that impressed Southerners, even as they feared he might be right about an impending slave revolt. Shortly before his execution, Brown prophesied, "the crimes of this guilty land : will never be purged away; but with Blood."[24]

Arguments for and against slavery

William Lloyd Garrison, the leading abolitionist, was motivated by a belief in the growth of democracy. Because the Constitution had a three-fifths clause, a fugitive slave clause and a 20-year extension of the Atlantic slave trade, Garrison once publicly burned a copy of the U. S. Constitution and called it "a covenant with death and an agreement with hell."[25]

In 1854, he said

I am a believer in that portion of the Declaration of American Independence in which it is set forth, as among self-evident truths, "that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness." Hence, I am an abolitionist. Hence, I cannot but regard oppression in every form—and most of all, that which turns a man into a thing—with indignation and abhorrence.[26]

Wendell Phillips, one of the most ardent abolitionists, attacked the Slave Power and presaged disunion as early as 1845:

The experience of the fifty years… shows us the slaves trebling in numbers—slaveholders monopolizing the offices and dictating the policy of the Government—prostituting the strength and influence of the Nation to the support of slavery here and elsewhere—trampling on the rights of the free States, and making the courts of the country their tools. To continue this disastrous alliance longer is madness.… Why prolong the experiment?[27]

Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens said that the cornerstone of the South was "That the Negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition."[28]

Jefferson Davis said slavery "…was established by decree of Almighty God… it is sanctioned in the Bible, in both Testaments, from Genesis to Revelation… it has existed in all ages, has been found among the people of the highest civilization, and in nations of the highest proficiency in the arts."[29]

Robert E. Lee said, "There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil."[30]

State Rights

The "States' Rights" debate cut across the issues. Southerners argued that the federal government was strictly limited and could not abridge the rights of states as reserved in Amendment X, and so had no power to prevent slaves from being carried into new territories.[31] States' rights advocates also cited the fugitive slave clause in the Constitution to demand federal jurisdiction over slaves who escaped into the North. Anti-slavery forces took reversed stances on these issues.

Jefferson Davis said that a "disparaging discrimination" and a fight for "liberty" against "the tyranny of an unbridled majority" gave the Confederate states a right to secede.[32]

South Carolina's "Declaration of the Immediate Causes for Secession" started with an argument for states' rights for slaveowners in the South, followed by a complaint about states' rights in the North (such as granting blacks citizenship, or hampering the extradition of slaves), claiming that Northern states were not fulfilling their federal obligations.[33]

In 1860, Congressman Keitt of South Carolina said, "The anti-slavery party contend that slavery is wrong in itself, and the Government is a consolidated national democracy. We of the South contend that slavery is right, and that this is a confederate Republic of sovereign States."[34]

The South defined equality in terms of the equal rights of states,[35] and opposed the declaration that all men are created equal.[36]

Economics

16th President (1861–1865)

Regional economic differences

The South, Midwest and Northeast had quite different economic structures. Charles Beard in the 1920s made a highly influential argument to the effect that these differences caused the war (rather than slavery or constitutional debates). He saw the industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the agrarian Midwest against the Plantation South. Critics pointed out that his image of a unified Northeast was incorrect because the region was highly diverse with many different competing economic interests. In 1860-61, most business interests in the Northeast opposed war. After 1950, only a few historians accepted the Beard interpretation, though it was picked up by libertarian economists.[37] As Historian Kenneth Stampp -- who abandoned Beardianism after 1950, sums up the scholarly consensus:[38]

Most historians of the sectional conflict, whatever differences they may have on other matters, now see no compelling reason why the divergent economies of the North and South should have led to disunion and civil war; rather, they find stronger practical reasons why the sections, whose economies neatly complemented one another, should have found it advantageous to remain united. Beard oversimplified the controversies relating to federal economic policy, for neither section unanimously supported or opposed measures such as the protective tariff, appropriations for internal improvements, or the creation of a national banking system. Except for the nullification crisis of 1832-33, economic issues, though sometimes present, were not crucial in the various sectional confrontations. During the 1850s, federal economic policy gave no substantial cause for southern disaffection, for policy was largely determined by pro-Southern Congresses and administrations. Finally, the characteristic posture of the conservative northeastern business community was far from anti-Southern. Most merchants, bankers, and manufacturers were outspoken in their hostility to antislavery agitation and eager for sectional compromise in order to maintain their profitable business connections with the South. The conclusion seems inescapable that if economic differences, real though they were, had been all that troubled relations between North and South, there would be no substantial basis for the idea of an irrepressible conflict.

The regional economic differences of the North and South frequently appeared in the government's tariff policy. As Frank Taussig observed, "In the years between 1832 and 1860 there was great vacillation in the tariff policy of the United States."[1] The debate centered around whether the tariff schedule should favor free trade and duties for revenue only, or protectionism to encourage factories for manufactured goods. As the northeastern economy industrialized, protective tariffs were sought by the iron mills of Pennsylvania, western Virginia (West Virginia) and New Jersey and the textile factories of New England. Most northern merchants, bankers and especially railroads wanted low tariffs.[39]

Meanwhile, the South, in addition to much subsistence agriculture, depended upon large-scale production of export crops, primarily cotton and (to a lesser extent) tobacco, raised by slaves. The slaveowning plantations —which comprised less than a third of the white population—were export-dependent. Plantation owners typically accepted the theory that protective tariffs on iron and textiles hurt them, though they bought very little iron and only the cheapest cloth for the slaves. They believed cotton was in such heavy demand that Britain and France had no choice but to buy expensive southern cotton. Cotton fed industrial production and profits everywhere it was sent, to Europe or the northeastern United States. James M. McPherson suggests that what South Carolina nullifiers really feared was not so much high tariffs but centralization of Federal government power, which might eventually threaten slavery itself.[40]

Douglas Irwin notes that antebellum tariff policy was often determined by the crucial swing vote of the Midwest.[2] The Midwest supported the low Walker Tariff in 1846 and a further reduction in the Tariff of 1857. This section had an export economy of food crops giving them reason to side with the South at times, and its numerous railroads opposed tariffs on iron. Notably, there was no unanimity of support for a single tariff program even within each region. Northern farmers also depended upon exports; early railroad managers desired reduced tariffs on imported iron; many Northern Democrats opposed any federal role in the nation's infrastructure, and Southern Whigs such as Henry Clay favored it. Throughout the antebellum period though, majorities in the southern congressional delegation favored free trade while majorities from northeastern industrial states such as Pennsylvania consistently sought protection.

Tariffs were low and did not protect northern industry before 1861. The Tariff of 1857 was the lowest since 1816 and a great victory for the South. However the Panic of 1857 energized the iron protectionists to fight back. [41] The Morrill Tariff passed the House of Representatives on a strictly sectional vote on May 10, 1860. Pressures to pass the bill in the Senate quickly became a campaign issue for the Republican Party in the Northeast, while Southerners delayed voting on the tariff in the Senate until the following year. A heated battle of rhetoric from both sides compounded the tariff issue. Economist Henry C. Carey led the protectionist charge in Northern newspapers by blaming free trade for the economic recession and accompanying budget shortfalls. Southerners circulated copies of Thomas Prentiss Kettell's 1857 book Southern Wealth and Northern Profits, which argued that protective tariffs unduly burdened the slave states to the benefit of the north. The Morrill Tariff did not pass until after the deep South seceded--it was signed by President Buchanan (a Democrat) in March 1861 and took effect in April, the same month the fighting started. The tariff was rarely mentioned in the heated debates of 1860-61 over secession, although Robert Toombs of Georgia did denounce "the infamous Morrill bill" as where "the robber and the incendiary struck hands, and united in joint raid against the South."[3] The tariff also appeared in two secession documents of the states. South Carolina's secession convention published a declaration by Robert Barnwell Rhett that listed as its reason for secession "the consolidation of the North to rule the South, by the tariff and Slavery issues."[4] Georgia also published a declaration listing economic grievances such as the tariff [5], though it emphasized the future of slavery as the main cause.

Alexander Stephens, for example, mentioned tariffs in his "Cornerstone Speech", but said the main cause was slavery. Stephens had been previously sympathetic to tariffs though, and had argued against Toombs's critique of the Morrill bill (as well as secession itself) a few months prior.

The many compromises proposed to resolve the crisis in 1860-61 never included the tariff, but instead always focused on the slavery issue.[42] Economic historian Lee A. Craig points out, "In fact, numerous studies by economic historians over the past several decades reveal that economic conflict was not an inherent condition of North-South relations during the antebellum era and did not cause the Civil War."[43]

Free labor vs. pro-slavery arguments

Historian Eric Foner (1970) has argued that a free-labor ideology dominated thinking in the North, which emphasized economic opportunity. By contrast, Southerners described free labor as "greasy mechanics, filthy operators, small-fisted farmers, and moonstruck theorists."[44] They strongly opposed the homestead laws that were proposed to give free farms in the west, fearing the small farmers would oppose plantation slavery. Indeed, opposition to homestead laws was far more common in secessionist rhetoric than opposition to tariffs. [45] They argued that only a slave-owning society allowed the leisure for education and cultural refinement. They depicted slavery as a positive good for the slaves themselves, especially the Christianizing that had rescued them from the paganism of Africa.

Slavery in the territories

The specific political crisis that led to secession stemmed from a dispute over the expansion of slavery into new territories. The Republicans, while maintaining that Congress had no power over slavery in the states, asserted that it did have power to ban slavery in the territories. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 maintained the balance of power in Congress by adding Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state. It prohibited slavery in the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase Territory north of 36°30'N lat. (the southern boundary of Missouri). The acquisition of vast new lands after the Mexican-American War (1846–1848), however, reopened the debate—now focused on the proposed Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in territories annexed from Mexico. Though it never passed, the Wilmot Proviso aroused angry debate. Northerners argued that slavery would provide unfair competition for free migrants to the territories; slaveholders claimed Congress had no right to discriminate against them by preventing them from bringing their legal property there. The dispute led to open warfare in the Kansas Territory after it was organized by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This act repealed the prohibition on slavery there under the Missouri Compromise, and put the fate of slavery in the hands of the territory's settlers, a process known as "popular sovereignty". Fighting erupted between proslavery "border ruffians" from neighboring Missouri and antislavery immigrants from the North (including John Brown, among other abolitionists). Tensions between North and South now were violent.

Southern fears of modernization

In a broader sense, the North was rapidly modernizing in a manner deeply threatening to the South, for the North was not only becoming more economically powerful; it was developing new modernizing, urban values while the South was clinging more and more to the old rural traditional values of the Jeffersonian yeoman.[46] As James McPherson argues:[47]

- The ascension to power of the Republican Party, with its ideology of competitive, egalitarian free-labor capitalism, was a signal to the South that the Northern majority had turned irrevocably towards this frightening, revolutionary future.

Southern fears of Republican control

Southern secession was triggered by the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln because regional leaders feared that he would make good on his promise to stop the expansion of slavery and would thus put it on a course toward extinction. Many Southerners thought that even if Lincoln did not abolish slavery, sooner or later another Northerner would do so, and that it was thus time to quit the Union. The slave states, which had already become a minority in the House of Representatives, were now facing a future as a perpetual minority in the Senate and Electoral College against an increasingly powerful North.

A house divided against itself

Secession winter

Before Lincoln took office, seven states declared their secession from the Union, and established a Southern government, the Confederate States of America on February 9, 1861. They took control of federal forts and other properties within their boundaries, with little resistance from President Buchanan, whose term ended on March 3, 1861. Buchanan asserted, "The South has no right to secede, but I have no power to prevent them." One quarter of the U.S. Army—the entire garrison in Texas—was surrendered to state forces by its commanding general, David E. Twiggs, who then joined the Confederacy. By seceding, the rebel states would reduce the strength of their claim to the Western territories that were in dispute, cancel any obligation for the North to return fugitive slaves to the Confederacy, and assure easy passage in Congress of many bills and amendments they had long opposed.

The Confederacy

Seven Deep South cotton states seceded by February 1861, starting with South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. These seven states formed the Confederate States of America (February 4 1861), with Jefferson Davis as president, and a governmental structure closely modeled on the U.S. Constitution. In April and May 1861, four more slave states seceded and joined the Confederacy: Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.

The Union states

There were 23 states that remained loyal to the Union during the war: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. During the war, Nevada and West Virginia joined as new states of the Union. Tennessee and Louisiana were returned to Union control early in the war.

The territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington fought on the Union side. Several slave-holding Native American tribes supported the Confederacy, giving the Indian territory a small bloody civil war.

Border states

Main article: Border states (Civil War)

The Border states in the Union comprised West Virginia (which broke away from Virginia and became a separate state), and four of the five northernmost slave states (Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky).

Maryland had numerous pro-Confederate officials who tolerated anti-Union rioting in Baltimore and the burning of bridges. Lincoln responded with martial law and called for troops. Militia units that had been drilling in the North rushed toward Washington and Baltimore. Before the Confederate government realized what was happening, Lincoln had seized firm control of Maryland (and the separate District of Columbia), by arresting the entire Maryland statehouse and holding them without trial.

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted decisively to remain within the Union. When pro-Confederate Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, it was attacked by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and the rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of the state. (See also: Missouri secession). In the resulting vacuum the convention on secession reconvened and took power as the Unionist provisional government of Missouri.

Kentucky did not secede; for a time, it declared itself neutral. However, the Confederates broke the neutrality by seizing Columbus in September 1861. That turned opinion against the Confederacy, and the state reaffirmed its loyal status, while trying to maintain slavery. During a brief invasion by Confederate forces, Confederate sympathizers organized a secession convention, inaugurated a governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy. The rebel government soon went into exile and never controlled the state.

Union forces took control of the northwestern portions of Virginia in 1861-62, and residents seceded from Virginia and entered the Union in 1863 as West Virginia. Similar secessions appeared in east Tennessee, but were suppressed by the Confederacy. Jefferson Davis arrested over 3,000 men suspected of being loyal to the Union and held them without trial.[48]

Overview

Some 10,000 military engagements took place during the war, 40% of them in Virginia and Tennessee.[49] Separate articles deal with every major battle and some minor ones. This article only gives the broad outline. For more information see Battles of the American Civil War.

The war begins

- For more details on this topic, see Battle of Fort Sumter

Lincoln's victory in the presidential election of 1860 triggered South Carolina's declaration of secession from the Union. By February 1861, six more Southern states made similar declarations. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America and established their temporary capital at Montgomery, Alabama. A pre-war February peace conference of 1861 met in Washington in a failed attempt at resolving the crisis. The remaining eight slave states rejected pleas to join the Confederacy. Confederate forces seized all but three Federal forts within their boundaries (they did not take Fort Sumter); President Buchanan protested but made no military response aside from a failed attempt to resupply Fort Sumter via the ship Star of the West, and no serious military preparations. However, governors in Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania began buying weapons and training militia units to ready them for immediate action.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as President. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and called any secession "legally void". He stated he had no intent to invade Southern states, nor did he intend to end slavery where it existed, but that he would use force to maintain possession of federal property. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union.

The South sent delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties and enter into a peace treaty with the United States. Lincoln rejected any negotiations with Confederate agents on the grounds that the Confederacy was not a legitimate government, and that making any treaty with it would be tantamount to recognition of it as a sovereign government.

Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, was one of the three remaining Union-held forts in the Confederacy, and Lincoln was determined to hold it. Under orders from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Confederates under General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard bombarded the fort with artillery on April 12, forcing the fort's capitulation. Northerners reacted quickly to this attack on the flag, and rallied behind Lincoln, who called for all of the states to send troops to recapture the forts and to preserve the Union. With the scale of the rebellion apparently small so far, Lincoln called for 74,000 volunteers for 90 days. For months before that, several Northern governors had discreetly readied their state militias[6]; they began to move forces the next day.

Four states in the upper South (Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Virginia) which had repeatedly rejected Confederate overtures, now refused to send forces against their neighbors, declared their secession, and joined the Confederacy. To reward Virginia, the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond. The city was the symbol of the Confederacy; if it fell, the new nation would lose legitimacy. Richmond was in a highly vulnerable location at the end of a tortuous supply line.

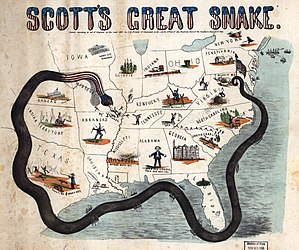

Anaconda Plan and blockade, 1861

Winfield Scott, the commanding general of the U.S. Army, devised the Anaconda Plan to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. His idea was that a Union blockade of the main ports would strangle the rebel economy; then the capture of the Mississippi River would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan, but overruled Scott's warnings against an immediate attack on Richmond.

- For more details on this topic, see Naval Battles of the American Civil War, Union blockade and Confederate States Navy

In May 1861, Lincoln proclaimed the Union blockade of all southern ports, which immediately shut down almost all international shipping to the Confederate ports. Violators risked seizure of the ship and cargo, and insurance probably would not cover the losses. Almost no large ships were owned by Confederate interests. By late 1861, the blockade shut down most local port-to-port traffic as well. Although few naval battles were fought and few men were killed, the blockade shut down King Cotton and ruined the southern economy. Some British investors built small, very fast "blockade runners" that brought in military supplies (and civilian luxuries) from Cuba and the Bahamas and took out some cotton and tobacco. When the U.S. Navy did capture blockade runners, the ships and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Union sailors. The British crews were released. The ironclad CSS Virginia's maiden voyage sank the blockade ship USS Cumberland and burned the USS Congress on her "trial run." The second day, the Battle at Hampton Roads took place between the ironclads USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia in March 1862, ending in a tactical draw; it was a strategic Union victory, for the blockade was sustained. Other naval battles included Island No. 10, Memphis, Drewry's Bluff, Arkansas Post, and Mobile Bay. The Second Battle of Fort Fisher virtually ended blockade running.

Eastern Theater 1861–1863

Because of the fierce resistance of a few initial Confederate forces at Manassas, Virginia in July 1861, a march by Union troops under the command of Major General Irvin McDowell on the Confederate forces there was halted in the First Battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas, whereupon they were forced back to Washington, D.C., by Confederate troops under the command of Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. It was in this battle that Confederate General Thomas Jackson received the nickname of "Stonewall" because he stood like a stone wall against Union troops. Alarmed at the loss, and in an attempt to prevent more slave states from leaving the Union, the U.S. Congress passed the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution on July 25 of that year, which stated that the war was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end slavery.

Major General George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26 (he was briefly general-in-chief of all the Union armies, but was subsequently relieved of that post in favor of Major General Henry W. Halleck), and the war began in earnest in 1862.

Upon the strong urging of President Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan attacked Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. Although McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston halted his advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, then General Robert E. Lee defeated him in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat. McClellan was stripped of many of his troops to reinforce General John Pope's Union Army of Virginia. Pope was beaten spectacularly by Lee in the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run in August.

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North, when General Lee led 45,000 men of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17 1862, the bloodiest single day in United States military history. Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided an opportunity for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Major General Ambrose Burnside. Burnside was soon defeated at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13 1862, when over twelve thousand Union soldiers were killed or wounded. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Major General Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker. Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. He was replaced by Major General George Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1 to July 3, 1863), the bloodiest battle in United States history, which is sometimes considered the war's turning point. Pickett's Charge on July 3, 1863 is often recalled as the high-water mark of the Confederacy, not just because it signaled the end of Lee's plan to pressure Washington from the north, but also because Vicksburg, Mississippi, the key stronghold to control of the Mississippi fell the following day. Lee's army suffered some 28,000 casualties (versus Meade's 23,000). However, Lincoln was angry that Meade failed to intercept Lee's retreat, and after Meade's inconclusive fall campaign, Lincoln decided to turn to the Western Theater for new leadership.

Western Theater 1861–1863

While the Confederate forces had numerous successes in the Eastern theater, they crucially failed in the West. They were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the Battle of Pea Ridge. Leonidas Polk's invasion of Kentucky enraged the citizens there who previously had declared neutrality in the war, turning that state against the Confederacy.

Nashville, Tennessee, fell to the Union early in 1862. Most of the Mississippi was opened with the taking of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee. The Union Navy captured New Orléans without a major fight in May 1862, allowing the Union forces to begin moving up the Mississippi as well. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented unchallenged Union control of the entire river.

General Braxton Bragg's second Confederate invasion of Kentucky was repulsed by General Don Carlos Buell at the confused and bloody Battle of Perryville, and he was narrowly defeated by General William Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee.

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga. Bragg, reinforced by Lieutenant General James Longstreet's corps (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans, despite the heroic defensive stand of General George Henry Thomas. Rosecrans retreated to Chattanooga, which Bragg then besieged.

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the west was Major General Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, by which the Union seized control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers; the Battle of Shiloh; the Battle of Vicksburg, cementing Union control of the Mississippi River and considered one of the turning points of the war. Grant marched to the relief of Rosecrans and defeated Bragg at the Third Battle of Chattanooga, driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening a route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.

Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861–1865

Though geographically isolated from the battles to the east, a few small-scale military actions took place west of the Mississippi River. Confederate incursions into Arizona and New Mexico were repulsed in 1862. Guerilla activity turned much of Missouri and Indian Territory (Oklahoma) into a battleground. Late in the war, the Union Red River Campaign was a failure. Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war, but was cut off from the rest of the Confederacy after the capture of Vicksburg in 1863 gave the Union control of the Mississippi River.

End of the war 1864–1865

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, and put Major General William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring an end to the war.[50] Grant devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy from multiple directions: Generals George Meade and Benjamin Butler were ordered to move against Lee near Richmond; General Franz Sigel (and later Philip Sheridan) were to attack the Shenandoah Valley; General Sherman was to capture Atlanta and march to the sea (Atlantic ocean); Generals George Crook and William W. Averell were to operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and General Nathaniel P. Banks was to capture Mobile, Alabama.

Union forces in the East attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's Overland Campaign") of the Eastern campaign. Grant's battles of attrition at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor resulted in heavy Union losses, but forced Lee's Confederates to fall back again and again. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 66,000 casualties in six weeks), kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. He pinned down the Confederate army in the Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.

Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Sheridan proved to be more than a match for General Jubal Early, and defeated him in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at the Battle of Cedar Creek. Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the Shenandoah Valley, a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman later employed in Georgia.

Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood along the way. The fall of Atlanta, on September 2, 1864, was a significant factor in the re-election of Lincoln as president. Hood left the Atlanta area to menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Union general John M. Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and George H. Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army.

Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unknown destination, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his celebrated "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic Ocean at Savannah in December 1864. Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves; there were no major battles along the March. When Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Confederate Virginia lines from the south, it was the end for Lee and his men.

Lee's army, thinned by desertion and casualties, was now much smaller than Grant's. Union forces won a decisive victory at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, forcing Lee to evacuate Petersburg and Richmond. The Confederate capital fell to the Union XXV Corps, comprising black troops. The remaining Confederate units fled west and after a defeat at Sayler's Creek, it became clear to Robert E. Lee that continued fighting against the United States was both tactically and logistically impossible.

Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. In an untraditional gesture and as a sign of Grant's respect and anticipation of folding the Confederacy back into the Union with dignity and peace, Lee was permitted to keep his officer's saber and his near-legendary horse, Traveller. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman on April 26, 1865, in Durham, North Carolina. On June 23, 1865, at Fort Towson in the Choctaw Nations' area of the Oklahoma Territory, Stand Watie signed a cease-fire agreement with Union representatives, becoming the last Confederate general in the field to stand down. The last Confederate naval force to surrender was the CSS Shenandoah on November 4, 1865, in Liverpool, England.

Slavery during the war

Lincoln initially declared his official purpose to be the preservation of the Union, not emancipation. He had no wish to alienate the thousands of slaveholders in the Union border states.

The issue of what to do with Southern slaves, however, would not go away: As early as May 1861, some slaves working on Confederate fortifications escaped to the Union lines, and their owner, a Confederate colonel, demanded their return under the Fugitive Slave Act. The response was to declare them "contraband of war"--effectively freeing them. Congress eventually approved this for slaves used by the Confederate military.

By 1862, when it became clear that this would be a long war, the question became more general. The Southern economy and military effort depended on slave labor; was it reasonable to protect slavery while blockading Southern commerce and destroying Southern production? As one Congressman put it, the slaves "…cannot be neutral. As laborers, if not as soldiers, they will be allies of the rebels, or of the Union."[51]

There was a range of positions on the final settlement of slavery; the same Congressman—and his fellow radicals—felt the victory would be profitless if the Slave Power continued. Conservative Republicans still hoped that the states could end slavery and send the freedmen abroad. Lincoln, and many others, agreed with both the aversion to slavery and to colonization; but all factions came rapidly to agree that the slaves of Confederates must be freed.[52]

At first, Lincoln reversed attempts at emancipation by Secretary of War Cameron and Generals Fremont and Hunter in order to keep the loyalty of the border states and the War Democrats. Lincoln then tried to persuade the border states to accept his plan of gradual, compensated emancipation and voluntary colonization, while warning them that stronger measures would be needed if the moderate approach was rejected. Only Washington, D. C. accepted Lincoln's gradual plan, and Lincoln issued his final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1 of 1863. In his letter to Hodges, Lincoln explained his belief that "If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong … And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling ... I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me."[53]

The Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862 and put into effect four months later, ended the Confederacy's hope of getting aid from Britain or France. Lincoln's moderate approach succeeded in getting border states, War Democrats and emancipated slaves fighting on the same side for the Union.

The Union-controlled border states (Kentucky, Missouri, Maryland, Delaware and West Virginia) were not covered by the Emancipation Proclamation. All abolished slavery on their own, except Kentucky. The great majority of the 4 million slaves were freed by the Emancipation Proclamation, as Union armies moved South. The 13th amendment, ratified December 6, 1865, finally freed the remaining 40,000 slaves in Kentucky, as well as 1,000 or so in Delaware.

Threat of international intervention

The best chance for Confederate victory was entry into the war by Britain and France. The Union, under Lincoln and Secretary of State William Henry Seward worked to block this, and threatened war if any country officially recognized the existence of the Confederate States of America. (None ever did.) In 1861, Southerners voluntarily embargoed cotton shipments, hoping to start an economic depression in Europe that would force Britain to enter the war in order to get cotton. Cotton diplomacy proved a failure as Europe had a surplus of cotton, while the 1860-62 crop failures in Europe made the North's grain exports of critical importance. It was said that "King Corn was more powerful than King Cotton", as US grain went from a quarter of the British import trade to almost half.[54]

When the U.K. did face a cotton shortage, it was temporary; being replaced by increased cultivation in Egypt and India. The war created employment for arms makers, iron workers, and British ships to transport weapons.[55]

Lincoln's announcement of a blockade of the Confederacy, a clear act of war, enabled Britain—followed by other European powers—to announce their neutrality in the dispute. This in turn enabled the Confederacy to begin to attempt to gain support and funds in Europe. President Jefferson Davis replaced his first two secretaries of state (Robert Toombs and Robert M. T. Hunter) with Judah P. Benjamin in early 1862. Although Benjamin had more international knowledge and legal experience, he failed to create a dynamic foreign policy for the Confederacy.

The first attempts to achieve European recognition of the Confederacy were dispatched on February 25, 1861 and led by William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre A. Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann. The British foreign minister Lord John Russell met with them, and the French foreign minister Edouard Thouvenel received the group unofficially. Neither Britain nor France ever promised formal recognition, for that meant war with the Union.

Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept as minister to Britain for the Union, and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the Union's blockade. Independent British maritime interests spent hundreds of millions of pounds to build and operate highly profitable blockade runners — commercial ships flying the British flag and carrying supplies to the Confederacy by slipping through the blockade. The officers and crews were British and when captured they were released. The Confederacy purchased several warships from commercial ship builders in Britain; the most famous, the Alabama, did considerable damage and led to serious postwar disputes. The Confederacy sent journalists Henry Hotze and Edwin De Leon to open propaganda stations to feed news media in Paris and London. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain. War loomed in late 1861 between the U.S. and Britain over the Trent Affair, involving the Union boarding of a British mail steamer to seize two Confederate diplomats. However, London and Washington were able to smooth over the problem after Lincoln released the two diplomats.

In 1862, the British considered mediation—though even such an offer would have risked war with the U.S. Lord Palmerston read Uncle Tom's Cabin three times when deciding on this. The Union victory in the Battle of Antietam caused them to delay this decision. The Emancipation Proclamation further reinforced the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. As the war continued, the Confederacy's chances with Britain grew hopeless, and they focused increasingly on France. Napoléon III proposed to offer mediation in January 1863, but this was dismissed by Seward. Despite some sympathy for the Confederacy, France's own seizure of Mexico ultimately deterred them from war with the Union. Confederate offers late in the war to end slavery in return for diplomatic recognition were not seriously considered by London or Paris.

Analysis of the Outcome

Could the South have won? A significant number of scholars believe that the Union held an insurmountable advantage over the Confederacy in terms of industrial strength, population, and the determination to win. Confederate actions, they argue, could only delay defeat. Southern historian Shelby Foote expressed this view succinctly in Ken Burns's television series on the Civil War: "I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back.… If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don't think the South ever had a chance to win that War."[56] After Lincoln defeated McClellan in the election of 1864, the threat of a political victory for the South was ended. At this point, Lincoln had succeeded in getting the support of the border states, War Democrats, Republicans, emancipated slaves and Britain and France. By defeating the Democrats and McClellan, he also defeated the Copperheads and their secessionist party platform. And he found military leaders like Grant and Sherman that were a match for Lee. From the end of 1864 on, there was no hope for the South.

The goals were not symmetric. To win independence, the South had to convince the North it could not win, but did not have to invade the North. To restore the Union, the North had to conquer vast stretches of territory. In the short run (a matter of months), the two sides were evenly matched. But in the long run (a matter of years), the North had advantages that increasingly came into play, while it prevented the South from gaining diplomatic recognition in Europe.

Long-term economic factors

Both sides had long-term advantages but the Union had more. To win the Union had to use its long-term resources to accomplish multiple goals, including control of the entire coastline, control of most of the population centers, control of the main rivers (especially the Mississippi and Tennessee), defeat of all the main Confederate armies, and finally seizure of Richmond. As the occupying force they had to station hundreds of thousands of soldiers to control railroads, supply lines, and major towns and cities. The long-term advantages widely credited by historians to have contributed to the Union's success include:

- The more industrialized economy of the North aided in the production of arms, munitions and supplies, as well as finances, and transportation. The graph shows the relative advantage of the USA over the Confederate States of America (CSA) at the start of the war. The advantages widened rapidly during the war, as the Northern economy grew, and Confederate territory shrank and its economy weakened.

- The Union population was 22 million and the South 9 million in 1861; the Southern population included more than 3.5 million slaves thus leaving the South's white population outnumbered by a ratio of more than four to one. The disparity grew as the Union controlled more and more southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy.

- The Union at the start controlled over 80% of the shipyards, steamships, river boats, and the Navy. It augmented these by a massive shipbuilding program. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire southern coastline.[57]

- Excellent railroad links between Union cities allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South which was unable to augment its much smaller rail system, repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance.[58]

Political and diplomatic factors

- The Union's more established government, particularly a mature executive branch which accumulated even greater power during wartime, gave a more streamlined conduct of the war, with minimal bickering between Lincoln and the governors. The failure of Davis to maintain positive and productive relationships with state governors damaged his ability to draw on regional resources.[59]

- A strong party system enabled the Republicans to mobilize soldiers and support at the grass roots, even when the war became unpopular. The Confederacy deliberately did not use parties.[60]

- The failure to win diplomatic or military support from any foreign powers cut the Confederacy from access to markets and to most imports. Its "King Cotton" misperception of the world economy led to bad diplomacy, such as the refusal to ship cotton before the blockade started.[61]

Military factors

- Strategically, the location of the capital Richmond tied Lee to a highly exposed position at the end of supply lines. Loss of its national capital was unthinkable for the Confederacy, for it would lose legitimacy as an independent nation. Washington was equally vulnerable, but if it had been captured, the Union would not have collapsed. [62]

- The Confederacy's tactic of invading the North (Antietam 1862, Gettysburg 1863, Nashville 1864) drained manpower strength, when it could not replace its losses.[63]

- The Union devoted much more of its resources to medical needs, thereby overcoming the unhealthy disease environment that sickened (and killed) more soldiers than combat did.[64]

- Despite the Union's many tactical blunders (like the Seven Days Battles), those committed by Confederate generals (such as Lee's miscalculations at the Battles of Gettysburg and Antietam) were far more serious—if for no other reason than that the Confederates could so little afford the losses.[65]

- Lincoln proved more adept than Davis in replacing unsuccessful generals with better ones.[66]

- Lincoln grew as a grand strategist, in contrast to Davis. The Confederacy never developed an overall strategy. It never had a plan to deal with the blockade. Davis failed to respond in a coordinated fashion to serious threats (such as Grant's campaign against Vicksburg in 1863; in the face of which, he allowed Lee to invade Pennsylvania).[67]

- The Emancipation Proclamation enabled African-Americans, both free blacks and escaped slaves, to join the Union Army. About 190,000 volunteered, further enhancing the numerical advantage the Union armies enjoyed over the Confederates. They fought in several key battles in the last two years of the war. [68]

- Finally, the Confederacy may have lacked the total commitment needed to win the war.[69] Lincoln and his team never wavered in their commitment to victory.

Civil War leaders and soldiers

- For more details on this topic, see Military leadership in the American Civil War

Most of the important generals on both sides had formerly served in the United States Army—some, including Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, during the Mexican-American War between 1846 and 1848. Most were graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

The senior Southern military commanders and strategists included Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson, James Longstreet, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, John Singleton Mosby, Braxton Bragg, John Bell Hood, James Ewell Brown "J.E.B." Stuart, and Jubal Early.

The senior Northern military commanders and strategists included Abraham Lincoln, Edwin M. Stanton, Winfield Scott, George B. McClellan, Henry W. Halleck, Joseph Hooker, Ambrose Burnside, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George Henry Thomas, and George Gordon Meade.

After 1980, scholarly attention turned to ordinary soldiers, women, and African Americans involved with the War. As James McPherson observed "The profound irony of the Civil War was that Confederate and Union soldiers… interpreted the heritage of 1776 in opposite ways. Confederates fought for liberty and independence from what they regarded as a tyrannical government; Unionists fought to preserve the nation created by the founders from dismemberment and destruction."[70]

Aftermath

The fighting ended with the surrender of the conventional Confederate forces. There was no significant guerrilla warfare. Many senior Confederate leaders escaped to Europe, to Mexico, or even to Brazil; Davis was captured and imprisoned for two years, but never brought to trial. Indeed, there were no treason trials for anyone.

Reconstruction

Northern leaders agreed that victory would require more than the end of fighting. It had to encompass the two war goals: Southern nationalism had to be totally repudiated, and all forms of slavery had to be eliminated. They disagreed sharply on the criteria for these goals. They also disagreed on the degree of federal control that should be imposed on the South, and the process by which Southern states should be reintegrated into the Union.

Reconstruction, which began early in the war and ended in 1877, involved a complex and rapidly changing series of federal and state policies. The long-term result came in the three "Civil War" amendments to the Constitution (the XIII, which abolished slavery, the XIV, which extended federal legal protections to citizens regardless of race, and the XV, which abolished racial restrictions on voting). Reconstruction ended in the different states at different times, the last three by the Compromise of 1877. For details on why the Fourteenth Amendment and Fifteenth Amendment were largely ineffective until the American Civil Rights movement, see Jim Crow laws, Ku Klux Klan, Plessy v. Ferguson, United States v. Cruikshank, Civil Rights Cases and Reconstruction.

Memories of the war

The war had a lasting impact on United States culture. Lincoln and Lee became iconic heroes. Every town and city built memorials to its heroic soldiers, battlefields became sacred places, and stories of the war became part of national folklore. By the 1890s, the veterans of the North and South had reconciled and were holding joint reunions. The South's strong support for the war against Spain in 1898 convinced the remaining doubters that the South was patriotic.[71]

However, for decades after the war, some Republican politicians "waved the bloody shirt," bringing up wartime casualties as an electoral tactic. Memories of the war and Reconstruction held the segregated South together as a Democratic block—the "Solid South"—in national politics for another century. A few debates surrounding the legacy of the war continue into the 21st century, especially regarding memorials and celebrations of Confederate heroes and battle flags.

See also

- List of American Civil War topics

- African Americans in the Civil War

- Canada and the American Civil War

- Casualties of the American Civil War

- List of Medal of Honor recipients

- Military history of the Confederate States

- National Civil War Museum

- Naming the American Civil War

- List of people associated with the American Civil War

- Official Records of the American Civil War

- Opposition to the American Civil War

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Photography and photographers of the American Civil War

- Rail transport in the American Civil War

- U.S. Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

- American Civil War spies

- Confederados

Notes

- ^ http://www.cwc.lsu.edu/other/stats/warcost.htm

- ^ Eric Foner. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (1970) ch 2

- ^ Dred Scott v. Sandford, U. S. Supreme Court, Roger Taney's decision, 1857

- ^ First Lincoln Douglas Debate at Ottawa, Illinois August 21, 1858

- ^ 1860 Census

- ^ J. G. Randall, Lincoln the President, 1997, vol 1, pages 237-241

- ^ Nevins, Ordeal of the Union 1:383; Pressly, 123-33, 278-81

- ^ James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom 1988 p 242, 255, 282-83. Maps on page 101 (The Southern Economy) and page 236 (The Progress of Secession) are also relevant

- ^ William E. Gienapp, "The Crisis of American Democracy: The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War." in Boritt ed. Why the Civil War Came 79-123

- ^ All God's Children; Fox Butterfield; page 17

- ^ Gienapp, "Crisis of American Democracy" p. 92; McPherson, pp 228-9

- ^ McPherson, Battle Cry p. 8; James Brewer Stewart, Holy Warriors: The Abolitionists and American Slavery (1976); Pressly, 270ff

- ^ David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage (2006) pp 186-192.

- ^ Mitchell Snay, "American Thought and Southern Distinctiveness: The Southern Clergy and the Sanctification of Slavery," Civil War History (1989) 35(4): 311-328; Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene D. Genovese, The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders' Worldview (2005), pp 505-27.

- ^ Schlesinger Age of Jackson, p.190

- ^ David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage (2006) p 197, 409; Stanley Harrold, The Abolitionists and the South, 1831-1861 (1995) p. 62; Jane H. and William H. Pease, "Confrontation and Abolition in the 1850's" Journal of American History (1972) 58(4): 923-937.

- ^ Eric Foner. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War (1970), p. 9

- ^ Curti, p. 381; Heidler, pp 1991-3.

- ^ McPherson, Battle Cry pages 88-91

- ^ Most of her slaveowners are "decent, honorable people, themselves victims" of that institution. Much of her description was based on personal observation, and the descriptions of Southerners; she herself calls them and Legree representatives of different types of masters.;Gerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, p.68; Stowe, Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin (1953) p. 39

- ^ Charles Edward Stowe, Harriet Beecher Stowe: The Story of Her Life (1911) p. 203. Historians are undecided whether Lincoln said the line.

- ^ Frederick J. Blue in American Historical Review (April 2006) v. 111 p 481-2.

- ^ David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (2005).

- ^ David Potter, The Impending Crisis: 1848-1861 (1976), chapter 14, quote from p. 367. Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing, pages 472-477 and The Emergence of Lincoln, vol 2, pages 71-97

- ^ Against Slavery: An Abolitionist Reader, (2000), page 26

- ^ http://members.aol.com/jfepperson/garrison.html

- ^ Wendell Phillips, "No Union With Slaveholders," Jan. 15, 1845, in Louis Ruchames, ed. The Abolitionists (1963) p. 196.

- ^ Alexander Stephen's Cornerstone Speech, Savannah; Georgia, March 21, 1861

- ^ Dunbar Rowland's Jefferson Davis, Volume 1, pages 286 and 316-317

- ^ http://www.civilwarhome.com/leepierce.htm 1856 letter by Lee in which he further states that slavery is worse for the white man than for the black, and that the blacks are better off in the US than in Africa

- ^ Resolved, That the union of these States rests on the equality of rights and privileges among its members, and that it is especially the duty of the Senate, which represents the States in their sovereign capacity, to resist all attempts to discriminate either in relation to person or property, so as, in the Territories -- which are the common possession of the United States -- to give advantages to the citizens of one State which are not equally secured to those of every other State. Jefferson Davis' Resolutions on the Relations of States, Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol, February 2, 1860, From The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Volume 6, pp. 273-76. Transcribed from the Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 658-59.

- ^ Jefferson Davis' Second Inaugural Address, Virginia Capitol, Richmond, February 22, 1862 Transcribed from Dunbar Rowland, ed., Jefferson Davis, Constitutionalist, Volume 5, pp. 198-203. Summarized in The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Volume 8, p. 55.

- ^ Declaration of the Immediate Causes Which Induce and Justify the Secession of South Carolina from the Federal Union - Adopted December 24, 1860

- ^ Lawrence Keitt, Congressman from South Carolina, in a speech to the House on January 25, 1860: Taken from a photocopy of the Congressional Globe supplied by Steve Miller.

- ^ "Who has been in advance of him in the fiery charge on the rights of the States, and in assuming to the Federal Government the power to crush and to coerce them? Even to-day he has repeated his doctrines. He tells us this is a Government which we will learn is not merely a Government of the States, but a Government of each individual of the people of the United States.", Jefferson Davis' reply in the Senate to William H. Seward, Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol, February 29, 1860, From The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Volume 6, pp. 277-84. Transcribed from the Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 916-18.

- ^ "We recognize the fact of the inferiority stamped upon that race of men by the Creator, and from the cradle to the grave, our Government, as a civil institution, marks that inferiority." - Jefferson Davis' reply in the Senate to William H. Seward, Senate Chamber, U.S. Capitol, February 29, 1860, - From The Papers of Jefferson Davis, Volume 6, pp. 277-84. Transcribed from the Congressional Globe, 36th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 916-18.

- ^ Woodworth, ed. The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1996), 145 151 505 512 554 557 684; Richard Hofstadter, The Progressive Historians: Turner, Beard, Parrington (1969); for one dissenter see Marc Egnal, . "The Beards Were Right: Parties in the North, 1840-1860." Civil War History 47, no. 1. (2001): 30-56.

- ^ Kenneth M. Stampp, The Imperiled Union: Essays on the Background of the Civil War (1981) p 198

- ^ Richard Hofstadter, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War," The American Historical Review Vol. 44, No. 1 (Oct., 1938), pp. 50-55 full text in JSTOR

- ^ McPherson, Ordeal by Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (1992)

- ^ Huston, James L. The Panic of 1857 and The Coming of the Civil War (1987)

- ^ Donald 2001 pp 134-38

- ^ Woodworth, ed. The American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1996), p. 505

- ^ Abraham Lincoln, The Man Behind the Myths, Stephen B. Oates, 1994, page 69

- ^ Richard Hofstafter, "The Tariff Issue on the Eve of the Civil War," The American Historical Review Vol. 44, No. 1 (1938), pp. 50-55 full text in JSTOR

- ^ J. Mills Thornton III, Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860 (1978)

- ^ James McPherson, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question," Civil War History 29 (Sept. 1983)

- ^ Mark Neely, Confederate Bastille: Jefferson Davis and Civil Liberties 1993 p. 10-11

- ^ Gabor Boritt, ed. War Comes Again (1995) p 247

- ^ Mark E. Neely Jr.; "Was the Civil War a Total War?" Civil War History, Vol. 50, 2004 pp 434+

- ^ James M. MacPherson, C. Vann Woodward, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Era of the Civil War, page 495

- ^ McPherson, Battle Cry page 355, 494-6, quote from George Julian on 495.

- ^ Lincoln's Letter to A. G. Hodges, April 4, 1864

- ^ McPherson, Battle Cry 386

- ^ Allen Nevins, War for the Union 1862-1863, pages 263-264

- ^ Ward 1990 p 272

- ^ McPherson 313-16, 392-3

- ^ Heidler, 1591-98

- ^ McPherson 432-44

- ^ Eric L. McKitrick, "Party Politics and the Union and Confederate War Efforts," in William Nisbet Chambers and Walter Dean Burnham, eds. The American party Systems (1965); Beringer 1988 p 93

- ^ Heidler, 598-603

- ^ Heidler, 1643-47

- ^ Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson. Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage (1982)

- ^ Resch 2: 112-14; Heidler, 603-4

- ^ Grady McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson. Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage (1982)

- ^ Weigley

- ^ Heidler, 564-72, 1185-90; T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and His Generals (1952)

- ^ John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation (1965)

- ^ Beringer et al (1986)

- ^ McPherson 1994 p 24.

- ^ Paul Herman Buck, The Road to Reunion, 1865-1900 (1937)

References

Overviews

- Beringer, Richard E., Archer Jones, and Herman Hattaway, Why the South Lost the Civil War (1986) influential analysis of factors; The Elements of Confederate Defeat: Nationalism, War Aims, and Religion (1988), abridged version, more readily available

- Catton, Bruce, The Civil War, American Heritage, 1960, ISBN 0-8281-0305-4, illustrated narrative

- Donald, David ed. Why the North Won the Civil War (1977) (ISBN 0-02-031660-7), short interpretive essays

- Donald, David et al. The Civil War and Reconstruction (latest edition 2001); 700 page survey

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, (2001), ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Fellman, Michael et al. This Terrible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2003), 400 page survey

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative (3 volumes), (1974), ISBN 0-394-74913-8. Highly detailed narrative covering all fronts

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), 900 page survey; Pulitzer prize

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union, an 8-volume set (1947-1971). the most detailed political, economic and military narrative; by Pulitzer Prize winner

- 1. Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847-1852; 2. A House Dividing, 1852-1857; 3. Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857-1859; 4. Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861; 5. The Improvised War, 1861-1862; 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863; 7. The Organized War, 1863-1864; 8. The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865

- Hay, John (1890). Abraham Lincoln: a History.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)- "Volume 1". to 1856; strong coverage of national politics