Vagina: Difference between revisions

Removed some text; duplicated information |

Undid revision 579533539 by Dark Mistress (talk) Not a duplication to the lead; nowhere in the lead is this stated. Simply stating "a sex organ" does not cover it. |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| DorlandsID = Vagina |

| DorlandsID = Vagina |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''vagina''' (from [[Latin]] ''vāgīna'', literally "sheath" or "[[scabbard]]") is a [[:wiktionary:fibromuscular|fibromuscular]] elastic [[cylinder (geometry)|tubular]] tract which is a [[sex organ]]. In humans, this passage leads from the opening of the vulva to the [[uterus]] (womb), but the vaginal tract ends at the [[cervix]]. Unlike men, who have only one genital orifice, women have two, the urethra and the vagina. The vaginal opening is much larger than the [[urethra|urethral opening]], and both openings are protected by the [[labia]].<ref>Clinical pediatric urology: A. Barry Belman, Lowell R. King, Stephen Alan Kramer (2002)</ref><ref name="Kinetics2009">{{cite book|last=Kinetics|first=Human|title=Health and Wellness for Life|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2GZ7N4wOeGYC&pg=PA221|accessdate=30 July 2013|date=15 May 2009|publisher=Human Kinetics 10%|isbn=978-0-7360-6850-5|page=221}}</ref> The inner mould of the vagina has a foldy texture which can create friction for the [[human penis|penis]] during intercourse. During arousal, the vagina gets moist to facilitate the entrance of the penis.<ref>[http://site.themarriagebed.com/biology/her-plumbing the female genitals] Retrieved 23 February 2012</ref> |

The '''vagina''' (from [[Latin]] ''vāgīna'', literally "sheath" or "[[scabbard]]") is a [[:wiktionary:fibromuscular|fibromuscular]] elastic [[cylinder (geometry)|tubular]] tract which is a [[sex organ]] and has two main functions: [[sexual intercourse]] and [[childbirth]]. In humans, this passage leads from the opening of the vulva to the [[uterus]] (womb), but the vaginal tract ends at the [[cervix]]. Unlike men, who have only one genital orifice, women have two, the urethra and the vagina. The vaginal opening is much larger than the [[urethra|urethral opening]], and both openings are protected by the [[labia]].<ref>Clinical pediatric urology: A. Barry Belman, Lowell R. King, Stephen Alan Kramer (2002)</ref><ref name="Kinetics2009">{{cite book|last=Kinetics|first=Human|title=Health and Wellness for Life|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=2GZ7N4wOeGYC&pg=PA221|accessdate=30 July 2013|date=15 May 2009|publisher=Human Kinetics 10%|isbn=978-0-7360-6850-5|page=221}}</ref> The inner mould of the vagina has a foldy texture which can create friction for the [[human penis|penis]] during intercourse. During arousal, the vagina gets moist to facilitate the entrance of the penis.<ref>[http://site.themarriagebed.com/biology/her-plumbing the female genitals] Retrieved 23 February 2012</ref> |

||

The Latinate plural "vaginae" is rarely used in English. [[Colloquialism|Colloquially]], the word ''vagina'' is often used to refer to the [[vulva]] or to the female genitals in general.<ref>[http://onlineslangdictionary.com/thesaurus/words+meaning+vulva+%28%27vagina%27%29,+female+genitalia.html Words meaning vulva ('vagina'), female genitalia] Online Slang Dictionary</ref> However, by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, ''vagina'' refers exclusively to the specific internal structure. |

The Latinate plural "vaginae" is rarely used in English. [[Colloquialism|Colloquially]], the word ''vagina'' is often used to refer to the [[vulva]] or to the female genitals in general.<ref>[http://onlineslangdictionary.com/thesaurus/words+meaning+vulva+%28%27vagina%27%29,+female+genitalia.html Words meaning vulva ('vagina'), female genitalia] Online Slang Dictionary</ref> However, by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, ''vagina'' refers exclusively to the specific internal structure. |

||

Revision as of 13:03, 31 October 2013

It has been suggested that Human vaginal size be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since May 2013. |

| Vagina | |

|---|---|

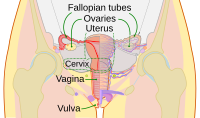

Vagina in the female human reproductive system. | |

Vulva with vaginal opening | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | urogenital sinus and paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | superior part to uterine artery, middle and inferior parts to vaginal artery |

| Vein | uterovaginal venous plexus, vaginal vein |

| Nerve | Sympathetic: lumbar splanchnic plexus Parasympathetic: pelvic splanchnic plexus |

| Lymph | upper part to internal iliac lymph nodes, lower part to superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 3523 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The vagina (from Latin vāgīna, literally "sheath" or "scabbard") is a fibromuscular elastic tubular tract which is a sex organ and has two main functions: sexual intercourse and childbirth. In humans, this passage leads from the opening of the vulva to the uterus (womb), but the vaginal tract ends at the cervix. Unlike men, who have only one genital orifice, women have two, the urethra and the vagina. The vaginal opening is much larger than the urethral opening, and both openings are protected by the labia.[1][2] The inner mould of the vagina has a foldy texture which can create friction for the penis during intercourse. During arousal, the vagina gets moist to facilitate the entrance of the penis.[3]

The Latinate plural "vaginae" is rarely used in English. Colloquially, the word vagina is often used to refer to the vulva or to the female genitals in general.[4] However, by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, vagina refers exclusively to the specific internal structure.

Location and structure

General structure

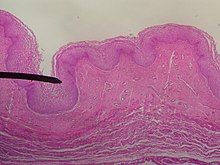

The human vagina is an elastic muscular canal that extends from the cervix to the vulva.[5] The internal lining of the vagina consists of stratified squamous epithelium. Beneath this lining is a layer of smooth muscle, which may contract during sexual intercourse and when giving birth. Beneath the muscle is a layer of connective tissue called adventitia.[6]

Although there is wide anatomical variation, the length of the unaroused vagina of a woman of child-bearing age is approximately 6 to 7.5 cm (2.5 to 3 in) across the anterior wall (front), and 9 cm (3.5 in) long across the posterior wall (rear), making posterior fornix deeper than anterior. During sexual arousal the vagina expands in both length and width. Its elasticity allows it to stretch during sexual intercourse and during birth of offspring. The vagina connects the superficial vulva to the cervix of the deep uterus.

If the woman stands upright, the vaginal tube points in an upward-backward direction and forms an angle of slightly more than 45 degrees with the uterus and of about 60 degrees to horizon.[7] The vaginal opening is at the caudal end of the vulva, behind the opening of the urethra. The upper one-fourth of the vagina is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch. Above the vagina is a cushion of fat called the mons pubis which surrounds the pubic bone and provides protective support during intercourse. The vagina, along with the inside of the vulva, is reddish pink in color, as are most healthy internal mucous membranes in mammals. A series of ridges produced by folding of the wall of the outer third of the vagina is called the vaginal rugae. They are transverse epithelial ridges and their function is to provide the vagina with increased surface area for extension and stretching.

The Bartholin's glands, located near the vaginal opening and cervix, were originally thought to be the primary source for vaginal lubrication, but they provide only a few drops of mucus for vaginal lubrication;[8] the significant majority of vaginal lubrication is now believed to be provided by plasma seepage from the vaginal walls, which is called vaginal transudation. Vaginal transudation, which initially forms as sweat-like droplets, is caused by vascular engorgement of the vagina (vasocongestion); this results in the pressure inside the capillaries increasing the transudation of plasma through the vaginal epithelium.[8][9][10] Before and during ovulation, the cervix's mucus glands secrete different variations of mucus, which provides an alkaline environment in the vaginal canal that is favorable to the survival of sperm. "Vaginal lubrication typically decreases as women age, but this is a natural physical change that does not normally mean there is any physical or psychological problem. After menopause, the body produces less estrogen, which, unless compensated for with estrogen replacement therapy, causes the vaginal walls to thin out significantly."[11]

The hymen is a membrane of tissue that surrounds or partially covers the external vaginal opening. The effects of sexual intercourse and childbirth on the hymen are variable. If the hymen is sufficiently elastic, it may return to nearly its original condition. In other cases, there may be remnants (carunculae myrtiformes), or it may appear completely absent after repeated penetration.[12][13] Additionally, the hymen may be lacerated by disease, injury, medical examination, masturbation or even physical exercise. For these reasons, it is not possible to definitively determine whether or not a girl or woman is a virgin by examining her hymen.[12][13][14][15]

The vagina in its full length - not only its upper part as had been thought for a long time - is a derivative of the embryonal Mullerian duct.[16] The upper 1/3 of vagina is supported by cardinal ligaments laterally and uterosacral ligaments posterolaterally. The middle 1/3 is supported by paracolpos and pelvic diaphragm. The lower 1/3 is supported by the pelvic diaphragm, urogenital diaphragm and perineal body.[7]

Vaginal ecosystem

The vagina is a nutrient rich environment that harbors a unique and complex microflora. It is a dynamic ecosystem that undergoes long term changes, from neonate to puberty and from the reproductive period (menarche) to menopause. Moreover, under the influence of hormones, such as estrogen (estradiol), progesterone and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), the vaginal ecosystem undergoes cyclic or periodic changes, i.e. during menses and pregnancy.[17][18][19][20]

Acidity

One important variable parameter is the vaginal pH, which varies significantly during a woman‘s lifespan, from 7.0 in premenarchal girls, to 3.8-4.4 in women of reproductive age to 6.5-7.0 during menopause without hormone therapy and 4.5-5.0 with hormone replacement therapy.[17] Estrogen, glycogen and lactobacilli are important factors in this variation.[17]

Microflora and possible role in acidification

The vagina of a newborn is affected by the residual maternal estrogen still present. At birth, the vaginal mucosa is rich in glycogen and the vagina becomes colonized by lactic-acid producing bacteria, such as Lactobacillus spp., within the first day after birth.[21] These estrogen effects will slowly disappear by the fourth week after birth and the glycogen content will diminish. The vaginal pH becomes neutral or alkaline, likely due to the almost absence of lactic-acid producing microorganisms.[18][22] In premenarchal girls, the vaginal microflora is composed of anaerobic and aerobic cocci and rods with low loads of lactobacilli, Gardnerella vaginalis and Mobiluncus spp.[17][22] During puberty, the estrogen levels rise until they reach the concentrations found in adult women. The estrogen causes the vaginal epithelium to thicken and the intracellular glycogen production to rise,[23] which consequently causes a shift in the composition of the vaginal microflora.[22] At this moment, lactobacilli, probably from the rectum,[24][25] become the most important inhabitants colonizing the vaginal econiche, utilizing the available glycogen, which is converted to lactic acid, resulting in the acidification (pH < 4.4) of the vagina.[17][24][25][26] In addition, besides lactic acid, the principal vaginal acidifier, other organic acids, i.e. acetic and linoleic acid, are also normally found in vaginal fluid.[27]

Acidity and estrogen vs. lactobacilli

The source of the lactic acid has been a matter of debate. Some studies suggest that the presence of estrogen and not Lactobacillus is primarily related to acidification of the vagina,[28] and even that lactobacilli cannot produce lactic acid from glycogen. The overall vaginal pH can be attributed to the total of estrogen mediated lactic acid production by the epithelial cells (producing only the L-isomer of lactate) and the lactic acid contribution by the endogenous vaginal bacteria (producing both D- and L-isomers of lactate).[27][29] Boskey et al.,[30] studying vaginal lactate production in 11 women, found that D-lactate (bacterial origin) in vaginal secretions ranged from 6% to 75%, with a mean of 55%. They concluded that these findings supported the role of Lactobacillus as the primary source for vaginal acidification, although the wide range found was not indicative for a dominant bacterial source of lactate in all women. Moreover, the midportion of the vagina has a higher pH than the vaginal fornix, although the lactobacilli concentration is uniform throughout the vaginal canal.[27] This is indicative for the fact that the vaginal mucosal metabolism may be more dominant in determining the final pH.[27]

However, in a pyrosequencing study by Ravel et al.[31] of the vaginal microflora of 396 asymptomatic North American women, representing four ethnic groups (white, black, Hispanic, and Asian), the higher median pH values in Hispanic (pH 5.0 ± 0.59) and black (pH 4.7 ± 1.04) women reflected a higher prevalence of communities not dominated by Lactobacillus spp. in these two ethnic groups, when compared with Asian (pH 4.4 ± 0.59) and white (pH 4.2 ± 0.3) women. Ravel et al.[31] found that the lowest pH values were associated with vaginal ecosystems dominated by L. iners and L. crispatus, and the highest pH values were associated with vaginal ecosystems not dominated by species of Lactobacillus.[31][32] The results of Ravel may be controversial for L.iners, which was strongly associated with Bacterial vaginosis-like vaginal microflora, which is characterized by alkaline pH.[33][34] Hummelen et al.[32] stated in their pyrosequencing study that L. crispatus is associated with a low pH, but when L. crispatus is not present, a large fraction of L. iners is required to predict a low pH.[32] Nevertheless, these results indicate that bacteria play an important role in the acidification of the vagina and more research, e.g. regarding the resource of glycogen, used to produce lactic acid and regarding the bacterial species that can metabolize glycogen, is needed to understand the various factors that govern vaginal pH.

Immune system

Next to the protective effects of pH and the endogenous vaginal microflora, pathogen colonization is also prevented by the local components of the innate and acquired immune systems.[35] The innate immune system recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) on microbial pathogens and includes soluble factors (e.g. mannose-binding lectin, complement components, defensins, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) and nitric oxide), membrane-associated components (e.g. Toll-like receptors) and tissue-associated phagocytes (macrophages and neutrophils).[27][35][36][37] The vaginal adaptive (acquired) immunity produces locally IgG and IgA, which will recognize and bind to specific antigens on microorganisms in the vagina.[38] For instance, an IgA response against G. vaginalis vaginolysin has been reported and a correlation between this response and BV has been shown.[39][40]

Finally, after the reproductive years, women enter the menopause, which is characterized by the cessation of menstruation because of the loss of follicular activity.[19] The circulating estrogen levels are low and the glycogen content is low to absent, resulting in a rise of the vaginal pH, and consequently the vagina is colonized by bacteria associated with intermediate/disturbed vaginal microflora.[18][19][41][42] It has been shown that estrogen therapy can augment the loads of lactobacilli, which in turn can diminish the increased risk for BV and urinary tract infections.[41][43] However, the absence of lactobacilli by itself is not related to an elevated prevalence of BV,[44] and estrogen replacement may merely potentiate the effect of lactobacilli present on the vaginal pH.[45]

The vaginal ecosystem is under the influence of many factors, endogenous (hormonal, innate immunity, ethnicity), as well as exogenous (behavioral factors, such as sexual activity, cigarette smoking, douching and antibiotic treatment in general),[46][47][48] that are determinative for the vaginal health. The endogenous susceptibility for disturbance of the vaginal microflora and for infections is determined by the genetic characteristics of each individual woman,[31][35] the specific composition of her vaginal microflora at a certain point in time and the genotypic differences between the vaginal lactobacilli present (at species and strain level).[49][50]

Function

The vagina has several biological functions.

Sexual activity

The concentration of the nerve endings that lie close to the entrance of a woman's vagina (the lower third) can provide pleasurable sensation during sexual activity when stimulated in a way that the particular woman enjoys. However, the vagina as a whole has insufficient nerve endings for sexual stimulation and orgasm,[51][52][53][54] which is considered to make the process of child birth significantly less painful.[52] The outer one-third of the vagina, especially near the opening, contains the majority of the vaginal nerve endings, making it more sensitive to touch than the inner two-thirds of the vaginal barrel.[52][53][54]

The clitoris contains an abundance of nerve endings and is a sex organ of multiplanar structure with a broad attachment to the pubic arch and via extensive supporting tissue to the mons pubis and labia, centrally attached to the urethra and vagina. Clitoral tissue forms a tissue cluster with the vagina. The tissue is more extensive in some women than in others, which may contribute to orgasms experienced vaginally.[51][53][55] During sexual arousal, and particularly the stimulation of the clitoris, the walls of the vagina lubricate. This reduces friction that can be caused by various sexual activities.[11] With arousal, the vagina lengthens rapidly,[11] to an average of about 4 in.(10 cm), but can continue to lengthen in response to pressure. As the woman becomes fully aroused, the vagina tents (last ²⁄₃) expands in length and width, while the cervix retracts. The walls of the vagina are composed of soft elastic folds of mucous membrane which stretch or contract (with support from pelvic muscles) to the size of the inserted penis or other object,[11] stimulating the penis and helping to cause the male to experience orgasm and ejaculation, thus enabling fertilization.

An erogenous zone commonly referred to as the G-Spot (also known as the Gräfenberg Spot) is typically defined as being located at the anterior wall of the vagina, about five centimeters in from the entrance. Some women experience intense pleasure if the G-Spot is stimulated appropriately during sexual activity. A G-Spot orgasm may be responsible for female ejaculation, leading some doctors and researchers to believe that G-Spot pleasure comes from the Skene's glands, a female homologue of the prostate, rather than any particular spot on the vaginal wall.[56][57][58] Other researchers consider the connection between the Skene's glands and the G-Spot to be weak.[59][60][61] They contend that the Skene's glands do not appear to have receptors for touch stimulation, and that there is no direct evidence for their involvement.[61] The G-Spot's existence, and existence as a distinct structure, is still under dispute, as its location can vary from woman to woman and appears to be nonexistent in some women,[55][59][62][63] and it is hypothesized to be an extension of the clitoris and therefore the reason for vaginal orgasms.[51][55][64][65]

Childbirth

During childbirth, the vagina provides the channel to deliver the newborn from the uterus to its independent life outside the body of the mother. During birth, the elasticity of the vagina allows it to stretch to many times its normal diameter. The vagina is often referred to as the birth canal in the context of pregnancy and childbirth, though the term is, by definition, the area between the outside of the vagina and the fully dilated uterus.[66]

Uterine secretions

The vagina provides a path for menstrual blood and tissue to leave the body. In industrial societies, tampons, menstrual cups and sanitary napkins may be used to absorb or capture these fluids.

Clinical relevance

The vagina is self-cleansing and therefore usually needs no special treatment. Doctors generally discourage the practice of douching.[67] Since a healthy vagina is colonized by a mutually symbiotic flora of microorganisms that protect its host from disease-causing microbes, any attempt to upset this balance may cause many undesirable outcomes, including but not limited to abnormal discharge and yeast infection.

The vagina is examined during gynecological exams, often using a speculum, which holds the vagina open for visual inspection of the cervix or taking of samples (see pap smear). Medical activities involving the vagina, including examinations, administration of medicine, and inspection of discharges, are also referred to as being per vaginam (or p.v.).[68]

pH

The healthy vagina of a woman of child-bearing age is acidic, with a pH normally ranging between 3.8 and 4.5.[69] This is due to the degradation of glycogen to the lactic acid by enzymes secreted by the Döderlein's bacillus. This is a normal commensal of the vagina. The acidity retards the growth of many strains of pathogenic microbes.[70]

An increased pH of the vagina (with a commonly used cut-off of pH 4.5 or higher), can be caused by bacterial overgrowth, as occurs in bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, or rupture of membranes in pregnancy.[69]

Vaginismus

Vaginismus, not to be confused with vaginitis (an inflammation of the vagina), refers to an involuntary tightening of the vagina due to a conditioned reflex of the muscles in the area. It can affect any form of vaginal penetration, including sexual intercourse, insertion of tampons and menstrual cups, and the penetration involved in gynecological examinations. Various psychological and physical treatments are possible to help alleviate it.

Signs of disease

Common signs of vaginal disease are lumps, discharge and sores:

Lumps

The presence of unusual lumps in the wall or base of the vagina is always abnormal. The most common of these is Bartholin's cyst.[71] The cyst, which can feel like a pea, is formed by a blockage in glands which normally supply the opening of the vagina. This condition is easily treated with minor surgery or silver nitrate. Other less common causes of small lumps or vesicles are herpes simplex. They are usually multiple and very painful with a clear fluid leaving a crust. They may be associated with generalized swelling and are very tender. Lumps associated with cancer of the vaginal wall are very rare and the average age of onset is seventy years.[72] The most common form is squamous cell carcinoma, then cancer of the glands or adenocarcinoma and finally, and even more rarely, melanoma.

Discharge

Most vaginal discharges occur due to normal bodily functions such as menstruation or sexual arousal. Abnormal discharges, however, can indicate disease.

Normal vaginal discharges include blood or menses (from the uterus), the most common, and clear fluid either as a result of sexual arousal or secretions from the cervix. Other non-infective causes include dermatitis. Non-sexually transmitted discharges occur from bacterial vaginosis and thrush or candidiasis. The final group of discharges include the sexually transmitted diseases gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis. The discharge from thrush is slightly pungent and white, that from trichomoniasis more foul and greenish, and that from foreign bodies resembling the discharge of gonorrhea, greyish or yellow and purulent (pus-like).[73]

Sores

All sores involve a breakdown in the walls of the fine membrane of the vaginal wall. The most common of these are abrasions and small ulcers caused by trauma. While these can be inflicted during rape most are actually caused by excessive rubbing from clothing or improper insertion of a sanitary tampon. The typical ulcer or sore caused by syphilis is painless with raised edges. These are often undetected because they occur mostly inside the vagina. The sores of herpes which occur with vesicles are extremely tender and may cause such swelling that passing urine is difficult. In the developing world a group of parasitic diseases also cause vaginal ulceration such as Leishmaniasis but these are rarely encountered in the west. HIV/AIDS can be contracted through the vagina during intercourse but is not associated with any local vaginal or vulval disease.[74] All the above local vulvovaginal diseases are easily treated. Often only shame prevents patients from presenting for treatment.[75]

Route of administration

Intravaginal administration is a route of administration where the substance is applied to the inside of the vagina. Pharmacologically, it has the potential advantage to result in effects primarily in the vagina or nearby structures (such as the vaginal portion of cervix) with limited systemic adverse effects compared to other routes of administration.

Other animals

The vagina (along with the penis) is a general feature of animals in which the female is internally fertilised (other than by traumatic insemination). The shape of the vagina varies among different animals.

In placental mammals and marsupials, the vagina leads from the uterus to the exterior of the female body. In birds, monotremes, and some reptiles, it is the homologous part of the oviduct and leads from the shell gland to the cloaca. In some jawless fish, there is no oviduct nor vagina and instead the egg travels directly through the body cavity (and is fertilised externally as in most fish and amphibians). In insects and other invertebrates the vagina is part of the oviduct (see insect reproductive system).

See also

References

- ^ Clinical pediatric urology: A. Barry Belman, Lowell R. King, Stephen Alan Kramer (2002)

- ^ Kinetics, Human (15 May 2009). Health and Wellness for Life. Human Kinetics 10%. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7360-6850-5. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ the female genitals Retrieved 23 February 2012

- ^ Words meaning vulva ('vagina'), female genitalia Online Slang Dictionary

- ^ "Glossary". womenshealth.gov. 8 June 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Young, B, ed. (2006). Wheater's Functional Histology: A Text and Colour Atlas (5th ed.). Elsevier. p. 377. ISBN 978-0443068508.

- ^ a b Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier 2011. pp. 1-16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ a b Sloane, Ethel (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 32, 41–42. ISBN 9780766811423. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Pelvic Floor Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2004. p. 20. ISBN 0721691943. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Handbook for Conducting Research on Human Sexuality. Psychology Press. 2012. p. 143. ISBN 1135663408. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d "Vagina". health.discovery.com. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b Knight, Bernard (1997). Simpson's Forensic Medicine (11th ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114. ISBN 0-7131-4452-1.

- ^ a b Jacoby, David B.; Youngson, Robert M. (2005). Encyclopedia of Family Health (3rd ed.). Marshall Cavendish. p. 889. ISBN 0-7614-7486-2.

- ^ Rogers DJ, Stark M (1998). "The hymen is not necessarily torn after sexual intercourse". BMJ. 317 (7155): 414. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7155.414. PMC 1113684. PMID 9694770.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Perlman, Sally E. (2004). Clinical protocols in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Parthenon. p. 131. ISBN 1-84214-199-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cai Y (2009). "Revisiting old vaginal topics: conversion of the Müllerian vagina and origin of the "sinus" vagina". Int J Dev Biol 2009; 53:925-34. 53 (7): 925–34. doi:10.1387/ijdb.082846yc. PMID 19598112.

- ^ a b c d e Danielsson, D., P. K. Teigen, and H. Moi. 2011. The genital econiche: Focus on microbiota and bacterial vaginosis" Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1230:48-58

- ^ a b c Farage, M., and H. Maibach. 2006. Lifetime changes in the vulva and vagina. Arch. Gynecol.

- ^ a b c Farage, M. A., S. Neill, and A. B. MacLean. 2009. Physiological changes associated with the

- ^ Golub, S. 1992. Periods: From menarche to menopause. Sage Publications, Inc.

- ^ Marshall WA, T. J. 1981. Puberty. Heinemann.

- ^ a b c Thoma, M. E., R. H. Gray, N. Kiwanuka, S. Aluma, M.-C. Wang, N. Sewankambo, and M. J. Wawer. 2011. Longitudinal changes in vaginal microbiota composition assessed by Gram stain among never sexually active pre- and postmenarcheal adolescents in Rakai, Uganda. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 24:42-47.

- ^ Paavonen, J. 1983. Physiology and ecology of the vagina. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 40:31-35.

- ^ a b El Aila, N. A., I. Tency, G. Claeys, H. Verstraelen, B. Saerens, G. Lopes dos Santos Santiago, E. De Backer, P. Cools, M. Temmerman, R. Verhelst, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2009. Identification and genotyping of bacteria from paired vaginal and rectal samples from pregnant women indicates similarity between vaginal and rectal microflora. BMC Infect. Dis.9:167.

- ^ a b El Aila, N. A., I. Tency, B. Saerens, E. De Backer, P. Cools, G. Lopes dos Santos Santiago, H. Verstraelen, R. Verhelst, M. Temmerman, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2011. Strong correspondence in bacterial loads between the vagina and rectum of pregnant women. Res. Microbiol. 162:506-513.

- ^ Antonio, M. A., L. K. Rabe, and S. L. Hillier. 2005. Colonization of the rectum by Lactobacillus species and decreased risk of bacterial vaginosis" J. Infect. Dis 192:394-398.

- ^ a b c d e Linhares, I. M., P. R. Summers, B. Larsen, P. C. Giraldo, and S. S. Witkin. 2011. Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli" Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 204:120.e1-120.e5.

- ^ Weinstein L, H. J. 1939. The effect of estrogenic hormone on the H-ion concentration and the bacterial content of the human vagina with special reference to the Doderline bacillus" Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 37:698-703.

- ^ Gorodeski, G. I., U. Hopfer, C. C. Liu, and E. Margles. 2005. Estrogen acidifies vaginal pH by up-regulation of proton secretion via the apical membrane of vaginal-ectocervical epithelial cells. Endocrinol. 146:816-824.

- ^ Boskey, E. R., R. A. Cone, K. J. Whaley, and T. R. Moench. 2001. Origins of vaginal acidity:High D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source" Hum. Reprod 16:1809-1813.

- ^ a b c d Ravel, J., P. Gajer, Z. Abdo, G. M. Schneider, S. S. Koenig, S. L. McCulle, S. Karlebach, R. Gorle, J. Russell, C. O. Tacket, R. M. Brotman, C. C. Davis, K. Ault, L. Peralta, and L. J. Forney. 2011. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A.108:4680-4687.

- ^ a b c Hummelen, R., A. D. Fernandes, J. M. Macklaim, R. J. Dickson, J. Changalucha, G. B. Gloor, and G. Reid. 2010. Deep sequencing of the vaginal microbiota of women with HIV. PloS One 5:e12078.

- ^ De Backer, E., R. Verhelst, H. Verstraelen, M. A. Alqumber, J. P. Burton, J. R. Tagg, M. Temmerman, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2007. Quantitative determination by real-time PCR of four vaginal Lactobacillus species, Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae indicates an inverse relationship between L. gasseri and L. iners. BMC Microbiol. 7:115.

- ^ Verhelst, R., H. Verstraelen, G. Claeys, G. Verschraegen, L. Van Simaey, C. De Ganck, E. De Backer, M. Temmerman, and M. Vaneechoutte. 2005. Comparison between Gram stain and culture for the characterization of vaginal microflora: Definition of a distinct grade that resembles grade I microflora and revised categorization of grade I microflora. BMC Microbiol. 5:61.

- ^ a b c Witkin, S. S., I. M. Linhares, and P. Giraldo. 2007. Bacterial flora of the female genital tract:function and immune regulation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 21:347-354.

- ^ Klein, N. J. 2005. Mannose-binding lectin: Do we need it?" Mol. Immunol 42:919-924.

- ^ Wira, C. R., and J. V. Fahey. 2004. The innate immune system: Gatekeeper to the female reproductive tract. Immunol. 111:13-15.

- ^ Mestecky, J., and M. W. Russell. 2000. Induction of mucosal immune responses in the human genital tract. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 27:351-355.

- ^ Cauci, S., S. Driussi, R. Monte, P. Lanzafame, E. Pitzus, and F. Quadrifoglio. 1998. Immunoglobulin A response against Gardnerella vaginalis hemolysin and sialidase activity in bacterial vaginosis" Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 178:511-515.

- ^ Cauci, S., F. Scrimin, S. Driussi, S. Ceccone, R. Monte, L. Fant, and F. Quadrifoglio. 1996. Specific immune response against Gardnerella vaginalis hemolysin in patients with bacterial vaginosis" Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 175:1601-1605.

- ^ a b Burton, J. P., and G. Reid. 2002. Evaluation of the bacterial vaginal flora of 20 postmenopausal women by direct (Nugent score) and molecular (polymerase chain reaction and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis) techniques" J. Infect. Dis 186:1770-1780.

- ^ Hillier, S. L., and R. J. Lau. 1997. Vaginal microflora in postmenopausal women who have not received estrogen replacement therapy" Clin. Infect. Dis 25:S123-S126.

- ^ Stamm, W. E., and R. Raz. 1999. Factors contributing to susceptibility of postmenopausal women to recurrent urinary tract infections" Clin. Infect. Dis 28:723-725.

- ^ Cauci, S., S. Driussi, D. De Santo, P. Penacchioni, T. Iannicelli, P. Lanzafame, F. De Seta, F. Quadrifoglio, D. de Aloysio, and S. Guaschino. 2002. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal flora changes in peri- and postmenopausal women" J. Clin. Microbiol 40:2147-2152.

- ^ Ginkel, P. D., D. E. Soper, R. C. Bump, and H. P. Dalton. 1993. Vaginal flora in postmenopausal women: The effect of estrogen replacement. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 1:94-97.

- ^ Cherpes, T. L., S. L. Hillier, L. A. Meyn, J. L. Busch, and M. A. Krohn. 2008. A delicate balance: Risk factors for acquisition of bacterial vaginosis include sexual activity, absence of hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli, black race, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex. Transm. Dis. 35:78-83.

- ^ Verstraelen, H. 2008. Bacterial vaginosis: A sexually enhanced disease. Int. J. STD AIDS 19:575-576.

- ^ Verstraelen, H., R. Verhelst, M. Vaneechoutte, and M. Temmerman. 2010. The epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis in relation to sexual behaviour. BMC Infect. Dis. 10:81.

- ^ Martin, R., and J. E. Suarez. 2010. Biosynthesis and degradation of H2O2 by vaginal lactobacilli" Appl. Environ. Microbiol 76:400-405.

- ^ McLean, N. W., and I. J. Rosenstein. 2000. Characterisation and selection of a Lactobacillus species to re-colonise the vagina of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis. J. Med. Microbiol. 49:543-552.

- ^ a b c O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Wayne Weiten, Dana S. Dunn, Elizabeth Yost Hammer (2011). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. p. 386. ISBN 9781111186630. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2009). Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 590. ISBN 9780761479079. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ a b "I'm a woman who cannot feel pleasurable sensations during intercourse". Go Ask Alice!. 8 October 2004 (Last Updated/Reviewed on 17 October 2008). Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c Kilchevsky A, Vardi Y, Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I. (2012). "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011 (3): 719–26. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Crooks, R (1999). Our Sexuality. California: Brooks/Cole.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jannini E, Simonelli C, Lenzi A (2002). "Sexological approach to ejaculatory dysfunction". Int J Androl. 25 (6): 317–23. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00371.x. PMID 12406363.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jannini E, Simonelli C, Lenzi A (2002). "Disorders of ejaculation". J Endocrinol Invest. 25 (11): 1006–19. PMID 12553564.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Hines T (2001). "The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (2): 359–62. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.115995. PMID 11518892.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Santos, F Taboga, S. (2003). "Female prostate: a review about biological repercussions of this gland in humans and rodents" (PDF). Animal Reproduction. 3 (1): 3–18. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Alzate H Hoch Z (1986). "The "G spot" and "female ejaculation": a current appraisal". J Sex Marital Ther. 12 (3): 211–20. doi:10.1080/00926238608415407. PMID 3531529.

- ^ "The G-spot". health.discovery.com. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ "Finding the G-spot: Is it real?". CNN. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ^ Alexander, Brian (18 January 2012). "Does the G-spot really exist? Scientists can't find it". MSNBC.com. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers (1991). A New View of a Woman’s Body. Feminist Heath Press. p. 46. ISBN 0962994502.

- ^ "Princeton University's Wordnet search results for Birth Canal". Princeton. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ "Vaginal Problems — Home Treatment". Women's Health. WebMD, LLC. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ See, e.g., Colin Hinrichsen, Peter Lisowski, Anatomy Workbook (2007), p. 101: "Digital examination per vaginam are made by placing one or two fingers in the vagina".

- ^ a b Vaginal pH Test from Point of Care Testing, July 2009, at: University of California, San Francisco – Department of Laboratory Medicine. Prepared by: Patricia Nassos, PhD, MT and Clayton Hooper, RN.

- ^ Todar, Kenneth (2008). "The Nature of Bacterial Host-Parasite Relationships in Humans". Online Textbook of Bacteriology. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ "Bartholin cyst". MayoClinic.com. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Manetta A, Pinto JL, Larson JE, Stevens CW, Pinto JS, Podczaski ES (1988). "Primary invasive carcinoma of the vagina". Obstet Gynecol. 72 (1): 77–81. PMID 3380510.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Spence D, Melville C (2007). "Vaginal discharge". BMJ. 335 (7630): 1147–51. doi:10.1136/bmj.39378.633287.80. PMC 2099568. PMID 18048541.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Hiv/Aids". MayoClinic.com. 11 August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Butcher J (1999). "Female sexual problems II: sexual pain and sexual fears". BMJ. 318 (7176): 110–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7176.110. PMC 1114576. PMID 9880287.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)