1989 (album)

| 1989 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Standard cover[note 1] | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | October 27, 2014 | |||

| Recorded | c. 2013–2014 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | Synth-pop | |||

| Length | 48:41 | |||

| Label | Big Machine | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Taylor Swift chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from 1989 | ||||

| ||||

1989 is the fifth studio album by American singer-songwriter Taylor Swift. It was released on October 27, 2014, by Big Machine Records. Following the release of her genre-spanning fourth studio album Red (2012), noted for pop hooks and electronic elements, the media questioned the validity of Swift's status as a country artist. Inspired by 1980s synth-pop to create a record that shifted her sound and image from country to mainstream pop, Swift enlisted Max Martin as co-executive producer, and titled her fifth album after her birth year as a symbolic rebirth of her artistry. The album is also a reference to the 1980s audio aesthetics of the album.

The album's synth-pop sound is characterized by heavy synthesizers, programmed drums, and processed backing vocals. Swift wrote the songs inspired by her personal relationships, which had been a trademark of her songwriting. The songs on 1989 express lighthearted perspectives, departing from her previous hostile attitude towards failed romance. Swift and Big Machine promoted the album extensively through product endorsements, television, radio appearances and social media. They pulled 1989 from free streaming services such as Spotify, prompting an industry discourse on the impact of streaming on music sales.[note 3]

After the album's release, Swift embarked on the 1989 World Tour, which was the highest-grossing tour of 2015. The album was supported by seven singles, including three US Billboard Hot 100 number ones: "Shake It Off", "Blank Space", and "Bad Blood". Critics praised Swift's songwriting in 1989 for offering emotional engagement that they found uncommon in the mainstream pop scene. Meanwhile, the synth-pop production raised questions regarding Swift's authenticity as a lyricist. The album appeared on several publications' lists of the best albums of the 2010s and featured in Rolling Stone's 2020 revision of their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. At the 58th Grammy Awards in 2016, 1989 won Album of the Year and Best Pop Vocal Album, making Swift the first female solo artist to win Album of the Year twice.

1989 was a commercial success. In the US, Swift became the first artist to have three albums each sell over one million copies within their first week of release. The album spent 11 weeks atop the Billboard 200 and received a ninefold platinum certification from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). It also earned multi-platinum certifications in Australia, Canada, and the UK, and has sold over 10 million pure copies worldwide.

Background

Until the release of her fourth studio album Red in October 2012, singer-songwriter Taylor Swift had been known as a country artist.[3][4] Red incorporates various pop and rock styles, transcending the country sound of her previous releases. The collaborations with renowned Swedish pop producers Max Martin and Shellback—including the top-five singles "We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together" and "I Knew You Were Trouble"—introduced straightforward pop hooks and new genres including electronic and dubstep to Swift's repertoire.[5][6] Swift and her label, Big Machine, promoted it as a country album; songs from Red impacted country radio and Swift made multiple appearances at country music awards shows.[7] When it ended, the album's associated world tour, running from March 2013 to June 2014, was the all-time highest-grossing country tour.[8] The diverse musical styles sparked a media debate over Swift's status as a country artist, to which she replied in an interview with The Wall Street Journal, "I leave the genre labeling to other people."[9]

Having been known as "America's Sweetheart" due to her wholesome and down-to-earth image,[10] Swift saw her reputation blemished by her history of romantic relationships with a series of high-profile celebrities. Her relationship with English singer Harry Styles during the promotion of Red was a particular subject for tabloid gossip.[11] She disliked the media portraying her as a "serial-dater", feeling it undermined her professional work, and became more reticent to discuss her personal life in public.[12] Most of the album's lyrics were derived from Swift's journal detailing her personal life; she had been known for autobiographical narratives in her songwriting since her debut.[13] A new inspiration this time was her relocation to New York City in March 2014, which gave Swift a sense of freedom to embark on new ideas.[13][14] Swift also took inspiration from the media scrutiny of her image to write satirical songs about her perceived image.[15][16]

Recording and production

Swift began songwriting for her fifth studio album in mid-2013 while touring to support Red.[17] For Red's follow-up, she sought to create a "blatant pop" record, departing from her country/pop experimentation. She believed that "if you chase two rabbits, you lose them both".[18] Greatly inspired by 1980s synth-pop,[19] she viewed the 1980s as an experimental period that embraced "endless possibilities" when artists abandoned the generic "drums-guitar-bass-whatever" song structure and experimented with stripped-down synthesizers, drum pads, and overlapped vocals.[13] She took inspiration from the music of artists from the period, such as Peter Gabriel and Annie Lennox, to make a synth-pop record that would convey her thoughts unburdened by heavy instrumentation.[note 4]

To ensure a smooth transition to pop, Swift recruited Max Martin and Shellback as major collaborators, in part because of their reputation as the biggest mainstream pop hitmakers at the time.[9] Speaking to the Associated Press in October 2013, Swift described them as "absolute dream collaborators" because they took her ideas in a different direction, which challenged her as a songwriter.[17] Scott Borchetta, president of Swift's then-label Big Machine, was initially skeptical of Swift's decision.[20] He failed to persuade Swift to record "three country songs",[20] and ultimately accepted that Big Machine would not promote the new songs to country radio.[21] Martin and Shellback produced seven of the thirteen tracks on the album's standard edition.[1] Swift credited Martin as co-executive producer because he also recorded and produced her vocals on tracks on which he was uncredited. This solidified Swift's vision of a coherent record rather than a mere "collection of songs".[20]

Another key figure on the album's production team was Jack Antonoff, with whom Swift had worked on the new wave-influenced song "Sweeter than Fiction" for the soundtrack of One Chance (2013).[22] Antonoff co-wrote and co-produced two tracks on the standard edition.[1] The first, "I Wish You Would", stemmed from his experimental sampling of snare drum instrumentation on Fine Young Cannibals' 1988 single "She Drives Me Crazy", one of their mutual favorite songs.[13] Antonoff played his sample to Swift on an iPhone and sent it to her to re-record.[13] The final track is a remix that retains the distinctive snare drums.[23] For "Out of the Woods", Antonoff sent his finished instrumental track to Swift while she was on a plane.[24] She sent him a voice memo containing the lyrics roughly 30 minutes later.[18] The song was the first time Swift composed lyrics for an existing instrumental.[25] Antonoff produced one more track for the album's deluxe edition, "You Are in Love".[19]

Swift contacted Ryan Tedder, with whom she had always wanted to work, by a smartphone voice memo.[26] He co-produced two songs—"Welcome to New York" and "I Know Places".[1] For "I Know Places", Swift scheduled a meeting with him at the studio after forming a fully developed idea on her own; the recording process the following day finalized it.[27] Tedder spoke of Swift's work ethic and perfectionism with Time: "Ninety-five times out of 100, if I get a track to where we're happy with it, the artist will say, 'That's amazing.' It's very rare to hear, 'Nope, that's not right.' But the artists I've worked with who are the most successful are the ones who'll tell me to my face, 'No, you're wrong,' two or three times in a row. And she [Swift] did."[28] For "Clean", Swift approached English producer Imogen Heap in London after writing the song's lyrics and melody. Heap helped to complete the track by playing instruments on it; the two finished recording after two takes in one day at Heap's studio.[19] Nathan Chapman, Swift's longtime collaborator, co-produced the track "This Love".[29] The album was mastered by Tom Coyne in two days at Sterling Sound Studio in New York City.[1][19] Swift finalized the record upon completing the Asian leg of the Red Tour in mid-2014.[30]

Music and lyrics

Overview

The standard edition of 1989 includes 13 tracks; the deluxe edition includes six additional tracks—three original songs and three voice memos.[31][32] The album makes heavy use of synthesizers, programmed drums, pulsating basslines, and processed backing vocals.[33] Because Swift aimed to recreate authentic 1980s pop, the album is devoid of contemporary hip hop or R&B crossover elements popular in mainstream music at the time.[34] Although Swift declared her move from country to pop on 1989, several reviewers, including The A.V. Club's Marah Eakin,[35] argued that Swift had always been more pop-oriented even on her early country songs.[4] The three voice memos on the deluxe edition contain Swift's discussions of the songwriting process and unfinished demos for three songs—"I Know Places", "I Wish You Would", and "Blank Space".[36] Myles McNutt, a professor in communications and arts, described the voice memos as Swift's effort to claim her authority over 1989, defying pop music's "gendered hierarchy" which had seen a dominance of male songwriters and producers.[32]

Although 1989's production was a dramatic change from that on Swift's country repertoire, her distinctive storytelling ability, nurtured by her country background, remained intact in her songwriting.[37][38] The songs are primarily about Swift's recurring themes of the emotions and reflections resulting from past romantic relationships.[33][39][40] However, 1989 showcased a maturity in Swift's perspectives: Rolling Stone observed that the album was her first not to villainize ex-lovers, but instead expressed "wistful and nostalgic" viewpoints on broken romance.[18] Pitchfork's Vrinda Jagota summarized 1989 as a "fully-realized fantasy of self-reliance, confidence, and ensuing pleasure", where Swift had ceased to dramatize failed relationships and learned to celebrate the moment.[41] The album's liner notes, which include a one-sentence hidden message for each of the 13 songs, collectively tell a story of a girl's tangled relationship. Ultimately, she finds that, "She lost him but she found herself and somehow that was everything."[42] Swift explained her shift in attitude to NPR: "In the past, I've written mostly about heartbreak or pain that was caused by someone else and felt by me. On this album, I'm writing about more complex relationships, where the blame is kind of split 50–50 ... even if you find the right situation relationship-wise, it's always going to be a daily struggle to make it work."[15]

Songs

Swift's feelings when she first moved to New York City inspired the opening track, "Welcome to New York", a synthesizer-laden song finding Swift embracing her newfound freedom.[29][43] "Blank Space", set over a minimal hip hop-influenced beat, satirizes the media's perception of Swift as a promiscuous woman who dates male celebrities only to gather songwriting material.[35][44] The production of "Style", a funk-flavored track, was inspired by "funky electronic music" artists such as Daft Punk;[19][45] its lyrics detail an unhealthy relationship and contain a reference to the American actor James Dean in the refrain.[46][47] "Out of the Woods" is an indietronica and synth-pop song featuring heavy synthesizers, layered percussions and looping background vocals, resulting in a chaotic sound.[48][49] Swift said that the song, which was inspired by a relationship that evoked constant anxiety because of its fragility, "best represents" 1989.[50][51] "All You Had to Do Was Stay" laments a past relationship and originated from Swift's dream of desperately shouting "Stay" to an ex-lover against her will.[52]

The dance-pop track "Shake It Off", sharing a loosely similar sentiment with "Blank Space", sees Swift expressing disinterest in her detractors and their negative remarks on her image.[53][54] The bubblegum pop song "I Wish You Would", which uses pulsing snare drums and sizzling guitars, finds Swift longing for the return of a past relationship.[46][55][56] Swift said that "Bad Blood", a track that incorporates heavy, stomping drums,[44] is about betrayal by an unnamed female peer (alleged to be Katy Perry, with whom Swift was involved in a feud that received widespread media coverage).[18][57] "Wildest Dreams" speaks of a dangerous affair with an apparently untrustworthy man and incorporates a sultry, dramatic atmosphere accompanied by string instruments.[19][45][58] On "How You Get the Girl", a bubblegum pop track featuring guitar strums over a heavy disco-styled beat, Swift hints at her desire to reunite with an ex-lover.[45][55][59] "This Love" is a soft rock-flavored electropop ballad;[43][44] music critic Jon Caramanica opined the song could be mistaken as "a concession to country" because of the production by Swift's longtime co-producer Nathan Chapman.[29]

The penultimate track of the standard edition is "I Know Places", which expresses Swift's desire to preserve an unstable relationship. Swift stated that it serves as a loose sequel to "Out of the Woods".[50] Accompanied by dark, intense drum and bass-influenced beats, the song uses a metaphor of foxes running away from hunters to convey hiding from scrutiny.[58][60] The final track, "Clean", is an understated soft-rock-influenced song, which talks about the struggles to escape from a toxic yet addictive relationship; the protagonist is "finally clean" after a destructive yet cleansing torrential storm.[43][61] "Wonderland", the first of the three bonus songs on the deluxe edition, alludes to the fantasy book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland to describe a relationship tumbling down a "rabbit hole".[23] The ballad "You Are in Love" finds Swift talking about an ideal relationship from another woman's perspective.[62] Swift was inspired by the relationship of Antonoff and his girlfriend at the time Lena Dunham, both of whom are close friends of hers.[63] The final song's title, "New Romantics", refers to the cultural movement in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[23] With a strong 1980s synth-pop sound, the song sees Swift reigniting her hopes and energy after the heartbreaks she had endured.[41][64]

Title and artwork

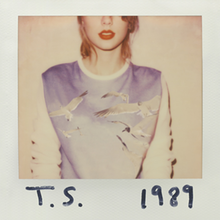

Swift named 1989 after her birth year, which corroborates the influence of 1980s synth-pop.[19] She described the title as a symbolic rebirth of her image and artistry, severing ties with the country stylings of her previous albums.[65] As creative director for the album's packaging,[1] Swift included pictures taken with a Polaroid instant camera—a photographic method popular in the 1980s.[66][67] The cover is a Polaroid portrait of Swift's face cut off at the eyes, which Swift said would bring about a sense of mystery: "I didn't want people to know the emotional DNA of this album. I didn't want them to see a smiling picture on the cover and think this was a happy album, or see a sad-looking facial expression and think, oh, this is another breakup record."[68][69] She is wearing red lipstick and a sweatshirt embroidered with flying seagulls.[66] Her initials are written with black marker on the bottom left, and the title 1989 on the bottom right.[67][69]

Each CD copy of 1989 includes a packet, one of five available sets, of 13 random Polaroid pictures, made up from 65 different pictures.[70] The pictures portray Swift in different settings such as backdrops of New York City and recording sessions with the producers.[71] The photos are out-of-focus, off-framed, with a sepia-tinged treatment, and feature the 1989 songs' lyrics written with black marker on the bottom.[67] Polaroid Corporation chief executive Scott Hardy reported that the 1989 Polaroid concept propelled a revival in instant film, especially among the hipster subculture who valued the "nostalgia and retro element of what [their] company stands for".[72]

Release and promotion

Swift marketed 1989 as her first "official pop" album.[73] To bolster sales, Swift and Big Machine implemented an extensive marketing plan.[74] As observed by Maryn Wilkinson, an academic specialized in media studies, Swift adopted a "zany" aspect for her 1989 persona.[note 5] As Swift had been associated with a hardworking and authentic persona through her country songs, her venture to "artificial, manufactured" pop required intricate maneuvering to retain her sense of authenticity.[76] She used social media extensively to communicate with her fan base; to attract a younger audience, she had promoted her country songs online previously.[77] Her social media posts showcased her personal life, making fans feel engaged with her authentic self and thus cemented their support while attracting a new fan base besides her already large one.[75][73] She also promoted the album through product endorsements with Subway, Keds and Diet Coke.[78] Swift held a live stream via Yahoo! sponsored by ABC News on August 18, where she announced the details of 1989 and released the lead single "Shake It Off",[79] which debuted atop the US Billboard Hot 100.[80] To connect further with her supporters, Swift selected a number of fans based on their engagement on social media and invited them to secret album-listening sessions, called "The 1989 Secret Sessions".[77] The sessions took place at her properties in Los Angeles, New York City, Nashville, Rhode Island, and London throughout September 2014.[81]

The album's standard and deluxe editions were released digitally on October 27, 2014.[82] In the US and Canada, the deluxe edition was available exclusively through Target Corporation.[26][83] The songs "Out of the Woods" and "Welcome to New York" were released through the iTunes Store as promotional singles on October 14 and 20, respectively.[84] 1989 was supported by a string of commercially successful singles,[85] including Billboard Hot 100 number ones "Blank Space" and "Bad Blood" featuring rapper Kendrick Lamar, and top-10 hits "Style" and "Wildest Dreams".[86] Other singles were "Out of the Woods", previously a promotional single,[87] and "New Romantics".[88] The deluxe edition bonus tracks, which had been available exclusively through Target, were released on the iTunes Store in the US in 2015.[89]

On November 3, 2014, Swift removed her entire catalog from Spotify, the largest on-demand streaming service at the time,[70] arguing that their ad-supported free service undermined the platform's premium service, which provides higher royalties for songwriters.[90] She had written an op-ed for The Wall Street Journal in July 2014, expressing her concerns over the decline of the album as an economic entity following the rise of free, on-demand streaming.[91] Big Machine and Swift kept 1989 only on paid subscription-required platforms such as Rhapsody and Beats Music.[74] This move prompted an industry-wide debate on the impact of streaming on declining record sales during the digital era.[73] In June 2015, Swift stated that she would remove 1989 from Apple Music, criticizing the service for not offering royalties to artists during their free three-month trial period.[92] After Apple announced that it would pay artists royalties during the free trial period, she agreed to leave 1989 on their service; she then featured in a series of commercials for Apple Music.[93][94] She re-added her entire catalog on Spotify in June 2017.[2] Swift began rerecording her first six studio albums, including 1989, in November 2020.[95] The decision came after talent manager Scooter Braun acquired the masters of Swift's first six studio albums, which Swift had been trying to buy for years, following her departure from Big Machine in November 2018.[96]

In addition to online promotion, Swift made many appearances on radio and television.[74] She performed at awards shows including the MTV Video Music Awards[97] and the American Music Awards.[98] Her appearances on popular television talk shows included Jimmy Kimmel Live!, The Ellen DeGeneres Show, Late Show with David Letterman and Good Morning America.[74] She was part of the line-up for the iHeartRadio Music Festival,[99] CBS Radio's "We Can Survive" benefit concert,[100] the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show[101] and the Jingle Ball Tour.[102] The album's supporting tour, the 1989 World Tour, ran from May to December 2015. It kicked off in Tokyo,[103] and concluded in Melbourne.[104] Swift invited various special guests on tour with her, including singers and fashion models the media called Swift's "squad" which received media coverage.[105] The 1989 World Tour was the highest-grossing tour of 2015, earning over $250 million at the box office.[106] In North America alone, the tour grossed $181.5 million, setting the record for highest-grossing US tour by a woman.[107] Swift broke this record in 2018 with her Reputation Stadium Tour.[108]

Critical reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AnyDecentMusic? | 7.4/10[109] |

| Metacritic | 76/100[110] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| The A.V. Club | B+[35] |

| Cuepoint (Expert Witness) | A−[112] |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| The Guardian | |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| NME | 7/10[43] |

| Pitchfork | 7.7/10[41] |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Spin | 7/10[60] |

1989 received generally positive reviews from contemporary critics;[9] most of them acknowledged Swift's mature perceptions.[113] The A.V. Club's Marah Eakin praised her shift from overtly romantic struggles to more positive themes of accepting and celebrating the moment.[35] Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph commended the album's "[sharp] observation and emotional engagement" that contrasted with lyrics found in "commercialised pop".[61] Alexis Petridis of The Guardian lauded Swift's artistic control that resulted in a "perfectly attuned" 1980s-styled synth-pop authenticity.[58]

The album's 1980s synth-pop production divided critics. In an enthusiastic review, The New York Times critic Jon Caramanica complimented Swift's avoidance of contemporary hip hop/R&B crossover trends, writing, "Ms. Swift is aiming somewhere even higher, a mode of timelessness that few true pop stars...even bother aspiring to."[29] Writing for Rolling Stone, Rob Sheffield characterized the record as "deeply weird, feverishly emotional, wildly enthusiastic".[59] In a review published by Cuepoint, Robert Christgau applauded her departure from country to experiment with new styles, but felt this shift was not radical.[112] NME reviewer Matthew Horton considered Swift's transition to pop "a success", save for the inclusion of the "soft-rock mush" of "This Love" and "Clean".[43] Shane Kimberlin writing for musicOMH deemed Swift's transition to pop on 1989 "not completely successful", but praised her lyrics for incorporating "enough heart and personality", which he found rare in the mainstream pop scene.[114]

Several reviewers lamented that the musical shift erased Swift's authenticity as a lyricist.[115] Slant Magazine's Annie Galvin observed that Swift maintained the clever songwriting that had distinguished her earlier releases, but was disappointed with the new musical style.[56] Entertainment Weekly's Adam Markovitz and Spin's Andrew Unterberger were critical of the heavy synthesizers, which undermined Swift's conventionally vivid lyrics.[60][116] AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine described the album as "a sparkling soundtrack to an aspirational lifestyle" that fails to transcend the "transient transparencies of modern pop".[111] Mikael Wood, in his review for the Los Angeles Times, found the album inauthentic for Swift's artistry, but acknowledged her effort to emulate the music of an era she did not experience.[45]

Accolades

1989 won Favorite Pop/Rock Album at the 2015 American Music Awards,[117] Album of the Year (Western) at the 2015 Japan Gold Disc Awards,[118] and Album of the Year at the 2016 iHeartRadio Music Awards.[119] It also earned nominations for Best International Pop/Rock Album at the 2015 Echo Music Prize,[120] International Album of the Year at the 2015 Juno Awards,[121] and Best International Album at the Los Premios 40 Principales 2015.[122] At the 58th Grammy Awards in 2016, the album won Album of the Year and Best Pop Vocal Album.[123] Swift became the first female solo artist to win Album of the Year twice—her first win was for Fearless (2008) in 2010.[124]

The album appeared on multiple publications' year-end lists of 2014, ranking at number one on the list by Billboard.[125] It was also picked as one of the best albums of the 2010s decade, including top-10 entries in The A.V. Club[126] and Slant Magazine.[127] According to Metacritic, it was the sixteenth most prominently acclaimed album on the decade-end lists.[128] In terms of audience reception, 1989 ranked at number 44 on Pitchfork's readers' poll for the 2010s decade.[129] In 2020, 1989 placed at number 393 on Rolling Stone's 2020 revision of their 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[130]

| Critical rankings for 1989 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Commercial performance

1989 was released amidst a decline in record sales brought about by the emergence of digital download and streaming platforms.[154] Swift's two previous studio albums, Speak Now (2010) and Red (2012), each sold over one million copies within one week, establishing her as one of the best-selling album artists in the digital era.[73] Given the music industry's climate, and Swift's decision to eschew her characteristic country roots that had cultivated a sizable fan base, the sales performance of 1989 was subject to considerable speculation among industry experts.[74][73] One week before its release, Rolling Stone reported that US retailers predicted the album would sell from 600,000 to 750,000 copies in its debut week.[154]

1989 debuted atop the US Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 1.287 million copies, according to data compiled by Nielsen SoundScan for the chart dated November 15, 2014. Swift became the first artist to have three albums each sell one million copies within the first week, and 1989 was the first album released in 2014 to exceed one million copies.[155] 1989 topped the Billboard 200 for 11 non-consecutive weeks[156] and spent the first full year after its release in the top 10 of the Billboard 200.[157] By September 2020, the album had spent 300 weeks on the chart.[158] 1989 exceeded sales of five million copies in US sales by July 2015, the fastest-selling album since 2004 up to that point.[note 6] With 6.215 million copies sold by the end of 2019, the album was the third-best-selling album of the 2010s decade in the US.[161] The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) certified the album 9× Platinum, which denotes nine million album-equivalent units.[162] All of its singles except "New Romantics" achieved platinum or multi-platinum certifications. The album tracks "Welcome to New York" and "This Love" were certified platinum, and "New Romantics", "All You Had to Do Was Stay", "How You Get the Girl", and "I Know Places" were certified gold.[163]

The album reached number one on the record charts of various European and Oceanic countries, including Australia, Belgium, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, and Switzerland.[164] In Canada, it was certified 6× Platinum[165] and was the fifth-best-selling album of the 2010s, with sales of 542,000 copies.[166] It was the fastest-selling album by a female artist of 2014 in the UK,[167] where it has sold 1.25 million copies and earned 4× Platinum certification.[168] 1989 became one of the best-selling digital albums in China, having sold one million units as of August 2019.[169] According to the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI), 1989 was the second best-selling album of 2014 and the third best-selling album of 2015, and had sold 10.1 million copies worldwide by the end of 2016.[170]

Legacy

1989's commercial success transformed Swift's image from a country singer-songwriter to a worldwide pop phenomenon.[28][115][171] The album was the second album to spawn five or more US top-10 singles in the 2010s decade,[note 7] and made Swift the second woman to have two albums each score five US top-10 hits.[note 8] Its singles received heavy rotation on US radio over a year and a half following its release, which Billboard described as "a kind of cultural omnipresence that's rare for a 2010s album".[174] The academic Shaun Cullen specializing in the humanities described Swift as a figure "at the cutting edge of postmillennial pop".[175] According to the BBC's Neil Smith, 1989 "[forged] a path for artists who no longer wish to be ghettoised into separated musical genres".[176] Ian Gormely of The Guardian called Swift the forefront of poptimism, led by 1989 which replaced dance/urban trends with ambition, proving that "chart success and clarity of artistic vison aren't mutually exclusive ideas."[177] The album's electronic-pop production expanded on Swift's next two studio albums, Reputation (2017) and Lover (2019), which solidified her status as a pop star.[105]

Along with 1989's success, Swift's new image as a pop star became a subject of public scrutiny. While Swift supported feminism—her first time expressing her political opinions[178]—her public appearances with singers and fashion models whom the media called her "squad" gave the impression that she did so just to keep her name afloat in news headlines.[105] Kristy Fairclough, a professor in popular culture and film, commented, "Her shifting aesthetic and allegiances appear confusing in an overall narrative that presents Taylor Swift as the centre of the cultural universe."[105] Swift's disputes with several celebrities, most notably rapper Kanye West, diminished her sense of authenticity that she had maintained.[94][note 9] Swift announced a prolonged hiatus following the 1989 World Tour because "people might need a break from [her]".[94] Her follow-up album Reputation (2017) was influenced in part by this tumultuous affair with the media.[180]

Retrospective reviews from GQ's Jay Willis,[181] New York's Sasha Geffen,[182] and NME's Hannah Mylrea praised how 1989 avoided contemporary hip hop and R&B crossover trends, making it a timeless album that represents the best of Swift's prowess. Mylrea praised it as the singer's best record and described it as an influence for younger musicians to embrace "pure pop", contributing to a growing trend of nostalgic 1980s-styled sound.[183] Geffen also attributed the album's success to its lyrics offering emotional engagement that is uncommon in pop.[182] Contemporary artists who cited 1989 as an influence included American singer-songwriter Conan Gray,[184] American actor and musician Jared Leto,[185] and British pop band the Vamps, who took inspiration from 1989 while composing their album Wake Up (2015).[186] Jennifer Kaytin Robinson cited 1989 as an inspiration for her 2019 directorial debut, Someone Great.[187] American rock singer-songwriter Ryan Adams released his track-by-track cover album of 1989 in September 2015. Finding it a "joyful" record, he listened to the album frequently to cope with his broken marriage in late 2014.[188] On his rendition, Adams incorporated acoustic instruments which contrast with the original's electronic production.[189][190] Swift was delighted with Adams' cover, saying to him, "What you did with my album was like actors changing emphasis."[191]

Track listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Welcome to New York" |

| 3:32 | |

| 2. | "Blank Space" |

|

| 3:51 |

| 3. | "Style" |

|

| 3:51 |

| 4. | "Out of the Woods" |

|

| 3:55 |

| 5. | "All You Had to Do Was Stay" |

|

| 3:13 |

| 6. | "Shake It Off" |

|

| 3:39 |

| 7. | "I Wish You Would" |

|

| 3:27 |

| 8. | "Bad Blood" |

|

| 3:31 |

| 9. | "Wildest Dreams" |

|

| 3:40 |

| 10. | "How You Get the Girl" |

|

| 4:07 |

| 11. | "This Love" | Swift |

| 4:10 |

| 12. | "I Know Places" |

|

| 3:15 |

| 13. | "Clean" |

|

| 4:30 |

| Total length: | 48:41 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Producers | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Wonderland" |

|

| 4:05 |

| 15. | "You Are in Love" |

|

| 4:27 |

| 16. | "New Romantics" |

|

| 3:50 |

| Total length: | 60:23 | |||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 17. | "I Know Places" (piano/vocal voice memo) |

| 3:36 |

| 18. | "I Wish You Would" (track/vocal voice memo) |

| 1:47 |

| 19. | "Blank Space" (guitar/vocal voice memo) |

| 2:11 |

| Total length: | 68:37 | ||

| No. | Title | Director(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Shake It Off" (music video) | Mark Romanek | 4:02 |

| 2. | "Shake It Off – The Cheerleaders Scene" | 3:52 | |

| 3. | "Shake It Off – The Ballerinas Scene" | 3:44 | |

| 4. | "Shake It Off – The Modern Dancers Scene" | 4:01 | |

| 5. | "Shake It Off – The Animators Scene" | 3:58 | |

| 6. | "Shake It Off – The Twerkers & Finger Tutting Scene" | 4:00 | |

| 7. | "Shake It Off – The Ribbon Dancers Scene" | 3:40 | |

| 8. | "Shake It Off – The Band, the Fans & the Extras Scene" | 4:13 | |

| Total length: | 31:30 | ||

Notes

- ^a signifies an additional producer

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the liner notes of 1989.[1]

- Production

|

|

- Instruments

|

|

Charts

Weekly charts

| Chart (2014–2021) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[164] | 1 |

| Austrian Albums (Ö3 Austria)[194] | 5 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[195] | 1 |

| Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[196] | 7 |

| Brazilian Albums (ABPD)[197] | 3 |

| Canadian Albums (Billboard)[198] | 1 |

| Czech Albums (ČNS IFPI)[199] | 17 |

| Danish Albums (Hitlisten)[200] | 2 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[201] | 1 |

| Finnish Albums (Suomen virallinen lista)[202] | 10 |

| French Albums (SNEP)[203] | 9 |

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[204] | 4 |

| Greek Albums (IFPI)[205] | 11 |

| Hungarian Albums (MAHASZ)[206] | 22 |

| Irish Albums (IRMA)[207] | 1 |

| Italian Albums (FIMI)[208] | 5 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[209] | 3 |

| South Korean Albums (Circle)[210] | 10 |

| South Korean International Albums (Circle)[211] | 2 |

| Mexican Albums (AMPROFON)[212] | 1 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[213] | 1 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[214] | 1 |

| Polish Albums (ZPAV)[215] | 17 |

| Portuguese Albums (AFP)[216] | 3 |

| Scottish Albums (OCC)[217] | 1 |

| South African Albums (RISA)[218] | 7 |

| Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[219] | 4 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[220] | 23 |

| Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[221] | 3 |

| Swiss Albums (SNEP Romandy)[222] | 1 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[223] | 1 |

| US Billboard 200[224] | 1 |

| US Independent Albums (Billboard)[225] | 8 |

Year-end charts

|

|

Decade-end charts

| Chart (2010s) | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[276] | 8 |

| Canadian Albums (Billboard)[166] | 5 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[277] | 25 |

| US Billboard 200[278] | 2 |

All-time charts

| Chart | Position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[note 10] | 4 |

| Irish Female Albums (IRMA)[280] | 36 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[note 11] | 33 |

| US Billboard 200[note 12] | 64 |

| US Billboard 200 (Women)[note 13] | 5 |

Certifications and sales

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[note 14] | 9× Platinum | 630,000‡ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[286] | 3× Platinum | 45,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[287] | Platinum | 40,000* |

| Brazil (Pro-Música Brasil)[287] Digital sales |

Gold | 20,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[165] | 6× Platinum | 542,000[note 15] |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[288] | Platinum | 20,000‡ |

| France (SNEP)[289] | Platinum | 100,000‡ |

| Germany (BVMI)[290] | Platinum | 200,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[291] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Japan (RIAJ)[293] | Platinum | 268,000[note 16] |

| Mexico (AMPROFON)[294] | 3× Platinum+Gold | 210,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[295] | Gold | 20,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[296] | 6× Platinum | 90,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[297] | 3× Platinum | 60,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[298] | 2× Platinum | 40,000‡ |

| Singapore (RIAS)[299] | 2× Platinum | 20,000* |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[300] | Gold | 20,000‡ |

| Sweden (GLF)[301] | Gold | 20,000‡ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[302] | Gold | 10,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[303] | 4× Platinum | 1,250,000[note 17] |

| United States (RIAA)[162] | 9× Platinum | 6,250,000[note 18] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

Release history

| Region | Date | Edition(s) | Format(s) | Label | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | October 27, 2014 | Standard | [305] | ||

| United States | Big Machine | [306][307] | |||

| Canada | Deluxe | CD | [83] | ||

| United States | |||||

| Germany |

|

|

|

[308] | |

| United Kingdom |

|

[309] | |||

| Various | Digital download | Big Machine | [82] | ||

| Australia | October 28, 2014 | Standard | CD | Universal | [310] |

| Japan | October 29, 2014 | Deluxe | CD+DVD | [193] | |

| Canada | December 9, 2014 | Standard | Vinyl | [311] | |

| United States | Big Machine | [312] | |||

| Turkey | December 10, 2014 | CD | [313] | ||

| United States | December 15, 2014 | Karaoke (digital download) | [314] | ||

| Mainland China | December 30, 2014 | Deluxe | CD | Universal | [315] |

| Canada | March 3, 2015 | Karaoke (digital download) | Big Machine | [316] | |

| United States | April 14, 2015 | Standard | Karaoke (CD+G/DVD) | [317] | |

| Canada | May 14, 2015 | Deluxe | Karaoke (CD+G) | [318] |

See also

- List of best-selling albums by year in the United States

- List of best-selling albums in China

- List of best-selling albums in the United States of the Nielsen SoundScan era

- List of best-selling albums of the 2010s in the United Kingdom

- List of best-selling albums of the 21st century

- List of best-selling albums by women

- Lists of fastest-selling albums

References

Notes

- ^ Deluxe edition cover has "1989" written across the image, with "D.L.X." written in the bottom right corner.

- ^ The location of The Hideaway Studio, where "Clean" was recorded, is not indicated in the liner notes of 1989.[1]

- ^ 1989 has been re-added and available on Spotify since June 2017.[2]

- ^ Swift admired Lennox's "way she conveys a thought, there's something really intense about it". Commenting on Gabriel's music, Swift said, "What he was doing in the '80s was so ahead of its time, because he was playing with a lot of synth-pop sounds, but kind of creating sort of an atmosphere behind what he was singing, rather than a produced track."[15]

- ^ Wilkinson used "zany" to describe Swift as "a figure who emphasises the pop 'performance' as one of hard work instead, because she exposed its construction as one that does not come 'naturally'".[75]

- ^ The record was later surpassed by Adele's 25 (2015).[159][160]

- ^ Following Katy Perry's Teenage Dream (2010)[172]

- ^ After Janet Jackson; her first album to have five US top-10 entries was Fearless (2008).[173]

- ^ Swift and West previously had a publicized adversary at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, where West interrupted Swift's acceptance speech for Best Female Video. Their so-called feud emerged again when West released his 2016 single "Famous", in which West incorporates a lyric referencing Swift. West claimed that he had asked for Swift's approval, which she objected to.[179]

- ^ Chart data for albums 1988–2021[279]

- ^ Chart data for albums 1988–2021[281]

- ^ Chart data for albums 1963–2015[282]

- ^ Chart data for albums 1963–2015[283]

- ^ The Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) certified 1989 Diamond (500,000 units) in 2015[284] and 9× Platinum (630,000 units) in 2019[285]

- ^ Canadian sales figures for 1989 as of January 2020[166]

- ^ Japanese sales figures for 1989 as of 2015[292]

- ^ UK sales figures for 1989 as of August 2019[168]

- ^ US sales figures for 1989 as of October 2020[304]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h 1989 (CD liner notes). Taylor Swift. Big Machine Records. 2014. BMRBD0500A.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b "Taylor Swift returns to Spotify on the day Katy Perry's album comes out". BBC News. June 9, 2017. Archived from the original on June 9, 2017. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (October 30, 2012). "Taylor Swift's 'Red' Sells 1.21 Million; Biggest Sales Week for an Album Since 2002". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b McNutt 2020, p. 77.

- ^ McNutt 2020, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Doyle, Patrick (July 15, 2013). "Taylor Swift: 'Floodgates Open' for Next Album". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Vinson, Christina (September 8, 2014). "Taylor Swift on Turning Away from Country Music on '1989'". Taste of Country. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Allen, Bob (July 3, 2014). "Taylor Swift's Red Wraps as All-Time Country Tour". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c McNutt 2020, p. 78.

- ^ Jo Sales, Nancy; Diehl, Jessica. "Taylor Swift's Telltale Heart". Vanity Fair. No. April 2013. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Chang, Bee-Shyuan (March 15, 2013). "Taylor Swift Gets Some Mud on Her Boots". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 22, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "On the Road with Best Friends Taylor Swift and Karlie Kloss". Vogue. February 13, 2015. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved November 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Eells, Josh (September 16, 2014). "Taylor Swift Reveals Five Things to Expect on '1989'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 16, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Peterson, Price (March 31, 2014). "Taylor Swift Moves into NYC Apartment Built Over Mysterious River of Pink Slime". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Block, Melissa (October 31, 2014). "'Anything That Connects': A Conversation With Taylor Swift" (Audio upload and transcript). NPR. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (October 15, 2015). "Taylor Swift on 'Bad Blood,' Kanye West, and How People Interpret Her Lyrics". GQ. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ a b Talbott, Chris (October 12, 2013). "Taylor Swift talks next album, CMAs and Ed Sheeran". Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 26, 2013. Retrieved December 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Eells, Josh (September 8, 2014). "Cover Story: The Reinvention of Taylor Swift". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Zollo, Paul (February 12, 2015). "The Oral History of Taylor Swift's '1989'". Cuepoint. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c Light, Alan (December 5, 2014). "Billboard Woman of the Year Taylor Swift on Writing Her Own Rules, Not Becoming a Cliche and the Hurdle of Going Pop". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Lee, Christina (June 11, 2014). "Max Martin Produced 'Most Of' Taylor Swift's Next Album". Idolator. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Grady (October 20, 2013). "Taylor Swift goes 80s bubblegum on new single 'Sweeter than Fiction'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wickman, Forrest (October 24, 2014). "Taylor Swift's 1989: A Track-by-Track Breakdown". Slate. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Hosken, Patrick (October 12, 2015). "Taylor Swift Breaks Down 'Shake It Off' Partly So We Could All Dance to It at Weddings". MTV News. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Mansfield, Brian (October 14, 2014). "How Taylor Swift created 'Out of the Woods'". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Perricone, Kathleen (October 20, 2014). "Taylor Swift Gives Details on Recording 'I Know Places' With Ryan Tedder". American Top 40. Archived from the original on January 19, 2015. Retrieved January 19, 2015.

- ^ McNutt 2020, pp. 81–82.

- ^ a b Dickey, Jack (November 13, 2014). "The Power of Taylor Swift". Time. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Caramanica, Jon (October 26, 2014). "A Farewell to Twang". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Garibaldi, Christina (May 30, 2014). "Taylor Swift Finally Reveals Details About Her Next Album". MTV News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Announced New Album 1989". Universal Music Canada. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b McNutt 2020, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b Aswad, Jem (October 24, 2014). "Album Review: Taylor Swift's Pop Curveball Pays Off With '1989'". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Mathieson, Craig (October 31, 2014). "Taylor Swift's new album 1989 defies expectations". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Eakin, Marah (October 28, 2014). "With 1989, Taylor Swift finally grows up". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ McNutt 2020, p. 80.

- ^ He, Richard (November 9, 2017). "Why Taylor Swift's '1989' Is Her Best Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Donella, Leah (September 26, 2018). "Taylor Swift Is The 21st Century's Most Disorienting Pop Star". NPR. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Empire, Kitty (October 26, 2014). "Taylor Swift: 1989 review – a bold, gossipy confection". The Observer. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Leedham, Robert (October 30, 2014). "Album Review: Taylor Swift – 1989". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on February 14, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Jagoda, Vrinda (August 19, 2019). "Taylor Swift: 1989 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Grady (October 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift: the hidden meaning in 1989's album notes – and an Aphex Twin mashup". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Horton, Matthew (October 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift – '1989'". NME. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Lansky, Sam (October 23, 2014). "Review: 1989 Marks a Paradigm Swift". Time. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Wood, Mikael (October 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift smooths out the wrinkles on sleek '1989'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Geffen, Sasha (October 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift – 1989 | Album Reviews". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ Petridis, Alexis (April 26, 2019). "Taylor Swift's singles – ranked". The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Mansfield, Brian (October 14, 2014). "How Taylor Swift created 'Out of the Woods'". USA Today. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Mylrea, Hannah (September 8, 2020). "Every Taylor Swift song ranked in order of greatness". NME. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ a b Iasimone, Ashley (October 11, 2015). "Taylor Swift Shares the Stories Behind 'Out of the Woods' & 'I Know Places'". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Inocencio, Marc. "Taylor Swift Unveils New Song 'Out of the Woods' off '1989' Album: Listen". iHeartRadio. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (October 19, 2015). "See Ryan Adams, Taylor Swift Discuss '1989,' Songwriting". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Feeney, Nolan (August 18, 2014). "Watch Taylor Swift Show Off Her Dance Moves in New 'Shake It Off' Video". Time. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (August 18, 2014). "Taylor Swift's 'Shake It Off' Single Review: The Country Superstar Goes Full Pop". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ a b Baesley, Corey (October 30, 2014). "Taylor Swift: 1989". PopMatters. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Galvin, Annie (October 27, 2014). "Review: Taylor Swift, 1989". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ^ Lang, Cady (July 17, 2019). "A Comprehensive Guide to the Taylor Swift-Katy Perry Feud From 2009 to the 'You Need to Calm Down' Happy Meal Reunion". Time. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Petridis, Alexis (October 24, 2014). "Taylor Swift: 1989 review – leagues ahead of the teen-pop competition". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Sheffield, Rob (October 24, 2014). "1989". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Unterberger, Andrew (October 28, 2014). "Taylor Swift Gets Clean, Hits Reset on New Album '1989'". Spin. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ a b c McCormick, Neil (October 26, 2014). "Taylor Swift, 1989, review: 'full of American fizz'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- ^ Greenwald, David (October 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift's '1989' loses more than country". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Gevinson, Tavi (May 7, 2015). "Taylor Swift Has No Regrets". Elle. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Sheffield, Rob (September 21, 2017). "All 129 of Taylor Swift Songs Ranked: New Romantics". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.

- ^ Wilson, Carl (October 29, 2014). "Contemplating Taylor Swift's Navel". Slate. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Bonanos, Christopher (October 27, 2014). "A Close Examination of Taylor Swift's 1989 Cover". New York. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c Williamson, Jason (December 15, 2014). "Beyond 1989: Taylor Swift and Polaroids". The Line of Best Fit. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Dickey, Jack (November 13, 2014). "Taylor Swift on 1989, Spotify, Her Next Tour and Female Role Models". Time. Archived from the original on October 6, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ a b Rothman, Michael (August 19, 2014). "Taylor Swift Explains Meaning Behind Cover of New Album '1989'". ABC News. Archived from the original on September 1, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Leonard, Devin (November 12, 2014). "Taylor Swift and Big Machine Are The Music Industry". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Garibaldi, Christina (October 27, 2014). "Here Are the Secret Messages Hidden in '1989'". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Swift album cover boosts vintage Polaroid sales". The New Zealand Herald. August 9, 2015. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Sisario, Ben (November 5, 2014). "Sales of Taylor Swift's '1989' Intensify Streaming Debate". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Christman, Ed; Caulfield, Keith; Gruger, William (November 7, 2014). "The Roadmap to Taylor Swift's Record-Breaking Week in 6 (Not So Easy) Steps". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ a b Wilkinson 2017, p. 441.

- ^ Wilkinson 2017, p. 442.

- ^ a b Lewis, Randy (October 28, 2014). "How does Taylor Swift connect with fans? 'Secret sessions' and media blitzes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ Hampp, Andrew (September 26, 2014). "Exclusive: Taylor Swift Teams With Subway, Diet Coke For #MeetTaylor Promotion". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ O'Keeffe, Kevin (August 19, 2014). "Taylor Swift Announces New Album '1989,' Premieres New Music Video 'Shake It Off'". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ Trust, Gary (August 27, 2014). "Taylor Swift's 'Shake It Off' Debuts At No. 1 On Hot 100". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 21, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ Stutz, Colin (October 16, 2014). "Watch Taylor Swift's '1989' Secret Sessions Behind The Scenes Video". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 10, 2019. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ a b 1989 digital releases worldwide:

"1989 by Taylor Swift". iTunes Store (global). Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

"1989 (Deluxe) by Taylor Swift". iTunes Store (global). Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2019. - ^ a b c "Taylor Swift – 1989 (Deluxe Edition) – Target Exclusive". Target Corporation. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (October 13, 2014). "Taylor Swift Previews 'Out Of The Woods,' New Track Out Tuesday: Listen". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.;

"Taylor Swift Reveals First Song on '1989': 'Welcome to New York'". ABC News Radio. October 20, 2014. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2014. - ^ a b "Top 100 Albums of the 2010s". Consequence of Sound. November 4, 2019. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ "Taylor Swift chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Strecker, Erin (December 22, 2015). "Taylor Swift's Video for 'Out of the Woods' Will Premiere on 'New Year's Rockin' Eve'". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ^ Iasimone, Ashley (February 20, 2015). "Taylor Swift's 'New Romantics' Set as Next '1989' Single". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 26, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Lipshutz, Jason (February 17, 2015). "Taylor Swift Releasing '1989' Bonus Songs to iTunes". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved February 27, 2019.;

"Wonderland – Single". iTunes Store (US). Archived from the original on June 3, 2015.;

"You Are In Love – Single". iTunes Store (US). Archived from the original on June 3, 2015. - ^ Knopper, Steve (November 8, 2014). "Taylor Swift Pulled Music From Spotify for 'Superfan Who Wants to Invest,' Says Rep". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 21, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ Richmond, Ben (November 4, 2014). "Taylor Swift Versus Spotify: How the Music Industry Is Still Fighting Streaming". Vice. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Peters, Mitchell (June 21, 2015). "Taylor Swift Pens Open Letter Explaining Why '1989' Won't Be on Apple Music". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 22, 2015. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ^ Rosen, Christopher (June 25, 2015). "Taylor Swift is putting 1989 on Apple Music". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 2017, p. 443.

- ^ Melas, Chloe (November 16, 2020). "Taylor Swift speaks out about sale of her masters". CTV News. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Swift wants to re-record her old hits". BBC News. August 22, 2019. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ Comer, M. Tye (August 24, 2014). "Taylor Swift Dazzles During 'Shake It Off' Performance at MTV VMAs". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Payne, Chris (November 23, 2014). "Taylor Swift Wins Dick Clark Award at AMAs, Hits Back at Spotify". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved July 4, 2015.

- ^ "iHeartRadio festival kicks off in Las Vegas". The Arizona Republic. September 20, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Edwards, Gavin (October 25, 2014). "Taylor Swift, Ariana Grande and Gwen Stefani Cover the Hollywood Bowl in Glitter". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Harvey, Lydia (December 3, 2014). "Taylor Swift prances around in lingerie during Victoria's Secret Fashion Show". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on February 6, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Stutz, Colin (December 6, 2014). "Taylor Swift Beats Laryngitis, Sam Smith, Ariana Grande Shine at KIIS FM Jingle Ball". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 8, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "Taylor Swift takes Tokyo by storm, kicking off 1989 World Tour". Los Angeles Times. May 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 24, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Derschowitz, Jessica (December 12, 2015). "Taylor Swift says goodbye to 1989 world tour in Australia". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Levine, Nick (August 21, 2019). "Taylor Swift's Lover: The struggle to maintain superstardom". BBC. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Waddell, Ray (December 11, 2015). "Live Music's $20 Billion Year: The Grateful Dead's Fare Thee Well Reunion, Taylor Swift, One Direction Top Boxscore's Year-End". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Frankenberg, Eric (August 21, 2018). "Taylor Swift Breaks Her Own Record for Highest-Grossing U.S. Tour by a Woman". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ Frankenberg, Eric (November 30, 2018). "Taylor Swift's Reputation Stadium Tour Breaks Record for Highest-Grossing U.S. Tour". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2018.

- ^ "1989 by Taylor Swift reviews". AnyDecentMusic?. Archived from the original on June 30, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "Reviews for 1989 by Taylor Swift". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved December 23, 2014.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "1989 – Taylor Swift". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved December 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (February 6, 2015). "Robert Christgau: Expert Witness". Cuepoint. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ Weber, Lindsey (October 28, 2014). "What Is Everyone Saying About Taylor Swift's 1989?". New York. Archived from the original on June 25, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Kimberlin, Shane (November 3, 2014). "Taylor Swift – 1989 | Album Review". musicOMH. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

- ^ a b McNutt 2020, p. 79.

- ^ Markovitz, Adam (November 11, 2014). "1989". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ "AMAs Winners List 2015". Billboard. November 22, 2015. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ 第29回 日本ゴールドディスク大賞 [The 29th Japan Gold Disc Awards] (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan. Archived from the original on March 5, 2015. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ "iHeartRadio Music Awards 2016: See the Full Winners List". Billboard. April 3, 2016. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2016.

- ^ "Die Helene-Fischer-Festspiele haben begonnen" (in German). March 27, 2015. Archived from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2016.

- ^ Bliss, Karen (January 27, 2015). "Magic!, Kiesza and Leonard Cohen Lead Juno Awards Nominations". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 30, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Premios 40 Principales 2015" (in Spanish). Los 40 Principales. Archived from the original on October 13, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2015.

- ^ "Grammy awards winners: the full list". The Guardian. February 15, 2016. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Lynch, Joe (February 19, 2016). "Taylor Swift Joins Elite Club to Win Grammy Album of the Year More Than Once: See the Rest". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "The 10 Best Albums of 2014". Billboard. December 11, 2014. Archived from the original on December 24, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "The 50 best albums of the 2010s". The A.V. Club. November 20, 2019. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ a b "The 100 Best Albums of the 2010s (page 1)". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ "Best Albums of the Decade (2010-19)". Metacritic. January 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ "2010s Readers' Poll Results". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020.

- ^ a b "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "American Songwriter's Top 50 Albums of 2014: Presented by D'Addario". American Songwriter. November 24, 2014. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ "The 20 best albums of 2014". The A.V. Club. December 8, 2014. Archived from the original on March 2, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2015.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Albums of the 2010s: Staff Picks". Billboard. November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- ^ Caramanica, Jon (December 11, 2014). "Jon Caramanica's Top 10 Albums of 2014". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 2014". Complex. December 18, 2014. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Naftule, Ashley (November 8, 2019). "The Top 25 Pop Albums of the 2010s". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 9, 2019.

- ^ "Best 50 albums of 2014". The Daily Telegraph. April 2, 2015. Archived from the original on April 9, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2018.

- ^ Adams, Sean (December 16, 2014). "Drowned In Sound's Favourite Albums of 2014". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 15, 2015.

- ^ "The best albums of 2014". The Guardian. November 26, 2014. Archived from the original on December 12, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben; Snapes, Laura; Curtin, April (September 13, 2019). "The 100 best albums of the 21st century". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved September 14, 2019.

- ^ "The Best Albums Of 2014: The Music's Writers' Poll". The Music. December 16, 2014. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ Hubbard, Michael (December 6, 2014). "musicOMH's Top 100 Albums Of 2014". musicOMH. Archived from the original on March 30, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ^ "NME's Greatest Albums of The Decade: The 2010s". NME. November 30, 2019. Archived from the original on December 11, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2019.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 2010s". Paste. October 9, 2019. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "The Village Voice's 42nd Pazz & Jop Music Critics Poll". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ "The 50 Best Albums of 2014". Pitchfork. December 17, 2014. Archived from the original on January 15, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ "The Best Albums of 2014". PopMatters. December 22, 2014. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ^ "50 Best Albums of 2014". Rolling Stone. December 2014. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^ "The 100 Best Albums of the 2010s". Rolling Stone. December 3, 2019. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Top 10 Best Albums of 2014". Time. December 2, 2014. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (December 16, 2014). "Ken Tucker's Top 9 Albums Of 2014, Plus A Book". NPR. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ "All The Best Albums Of The 2010s, Ranked". Uproxx. October 7, 2019. Archived from the original on October 11, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ^ Willman, Chris (December 20, 2019). "The Best Albums of the Decade". Variety. Archived from the original on March 7, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Knopper, Steve (October 21, 2014). "Can Taylor Swift's '1989' Save Ailing Music Industry?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 1, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (November 4, 2014). "Official: Taylor Swift's '1989' Debuts With 1.287 Million Sold In First Week". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 7, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (February 11, 2015). "Taylor Swift's '1989' Spends 11th Week at No. 1 on Billboard 200 Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (October 27, 2015). "Taylor Swift's '1989' Only Fifth Album to Spend First Year in Billboard 200's Top 10". Billboard. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (September 15, 2020). "Taylor Swift's '1989' Now One of Only Four Albums by Women to Spend 300 Weeks on Billboard 200 Chart". Billboard. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Caulfield, Keith (July 8, 2015). "Taylor Swift's '1989' Hits 5 Million in U.S. Sales, Making It the Fastest-Selling Album In Over 10 Years". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ Berenson, Tessa (December 11, 2015). "Adele's 25 Sells 5 Million Copies in the U.S." Time. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ "2019 Nielsen Year-End Report" (PDF). Billboard. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2020. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ a b "American album certifications – Taylor Swift – 1989". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum – Taylor Swift – Format: singles". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ a b "Australiancharts.com – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Canadian album certifications – Taylor Swift – 1989". Music Canada. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Nielsen 2019 Year End Report Canada" (PDF). Billboard. p. 41. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 2, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Moss, Liv (November 2, 2014). "Taylor Swift scores fastest selling female album of the year so far". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on November 2, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Copsey, Rob (August 22, 2019). "Taylor Swift's Official Top 20 biggest singles in the UK revealed". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2019.

- ^ Oakes, Tara (August 30, 2019). Jones, Gareth (ed.). "Taylor Swift's 'Lover' album breaks new record in China". Reuters. Archived from the original on August 30, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ Data compiled by the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry for each year:

2014: "IFPI Digital Music Report 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 10, 2016.

2015: "IFPI Global Music Report 2016" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 30, 2016.

2016: "Anuario Sgae de Las Artes Escenias, Musicales y Audiovisuales 2017" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2017. - ^ Hertweck, Nate (January 18, 2018). "Taylor Swift, '1989': For The Record". The Recording Academy. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved August 8, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Trevor (October 30, 2015). "From Michael Jackson's 'Thriller' to Taylor Swift's '1989': Albums with Five Top 10 Hot 100 Hits". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Trevor (August 18, 2020). "Juice WRLD's 'Legends Never Die' & The 27 Other Albums With Five or More Top 10 Hot 100 Hits". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 29, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Unterberger, Andrew (July 6, 2018). "While You Weren't Looking, Taylor Swift Scored Her Biggest 'Reputation' Radio Hit". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2020.

- ^ Cullen 2016, p. 37.

- ^ Smith, Neil (June 22, 2015). "Five ways Taylor Swift is changing the world". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 23, 2019. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ Gormely, Ian (December 3, 2014). "Taylor Swift leads poptimism's rebirth". The Guardian. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Hoby, Hermione (August 23, 2014). "Taylor Swift: 'Sexy? Not on my radar'". The Guardian. Retrieved November 14, 2020.

- ^ Snapes, Laura (August 24, 2019). "Taylor Swift: 'I was literally about to break'". The Guardian. Retrieved November 13, 2020.

- ^ Hiatt, Brian (September 30, 2019). "9 Taylor Swift Moments That Didn't Fit in Our Cover Story". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Willis, Jay (October 25, 2019). "Taylor Swift's 1989 Perfected the Pop Crossover Album". GQ. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Geffen, Sasha (November 10, 2017). "Revisiting Taylor Swift's '1989' Album". New York. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Mylrea, Hannah (July 24, 2020). "Taylor Swift: every single album ranked and rated". NME. Archived from the original on August 10, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Welby, Augustus (April 14, 2020). "Conan Gray: 'I always write about things that make me feel uncomfortable'". Tone Deaf. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Weiner, Natalie (July 12, 2015). "Jared Leto Listens to Taylor Swift's '1989' For Musical Inspiration: See His Reaction". Billboard. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Akingbade, Tobi (March 2, 2019). "The Vamps reveal they really want to work with Taylor Swift again: 'She revolutionised music'". Metro. Archived from the original on June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Hilary (August 25, 2019). "Taylor Swift Calls Rom-Com Inspiration Behind 'Lover' Song the 'Most Meta Thing That's Ever Happened to Me'". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 27, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- ^ O'Donnell, Kevin (September 21, 2015). "Ryan Adams 1989 interview: Indie icon opens up about covering Taylor Swift's smash album". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Zaleski, Annie (September 21, 2015). "Ryan Adams transforms Taylor Swift's 1989 into a melancholy masterpiece". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Winograd, Jeremy (October 21, 2015). "Review: Ryan Adams, 1989". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ Hendicott, James (October 19, 2015). "Taylor Swift tells Ryan Adams 'what you did with my album was like actors changing emphasis' – watch". NME. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ 1989 (digital booklet). Taylor Swift (deluxe ed.). Big Machine Records. 2014.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ a b "1989 (Deluxe) by Taylor Swift". Japan: HMV. Archived from the original on February 9, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Taylor Swift – 1989" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Taylor Swift – 1989" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Taylor Swift – 1989" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Brazil Albums: December 13, 2014". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- ^ "Taylor Swift Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 44.Týden 2014 on the field besides the words "CZ – ALBUMS – TOP 100" to retrieve the correct chart. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Taylor Swift – 1989" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Taylor Swift: 1989" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Taylor Swift – 1989" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- ^ "Official IFPI Charts Top-75 Albums Sales Chart" (in Greek). IFPI Greece. Archived from the original on November 10, 2014. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ "Album Top 40 slágerlista – 2014. 44. hét" (in Hungarian). MAHASZ. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ "Irish-charts.com – Discography Taylor Swift". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ "Italiancharts.com – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ 週間 CDアルバムランキング2014年11月10日付 [Weekly CD Albums Ranking 2014-11-10] (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on November 11, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "South Korea Circle Album Chart". On the page, select "2014.10.26~2014.11.01" to obtain the corresponding chart. Circle Chart Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ "South Korea Circle International Album Chart". On the page, select "2014.10.26~2014.11.01" to obtain the corresponding chart. Circle Chart Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "Los Más Vendidos 2015 – Mejor posición" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas (AMPROFON). Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Taylor Swift – 1989". Hung Medien. Retrieved November 7, 2014.