History of Thailand (2001–present)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| 21st-century Thailand | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 January 2001 – present | |||

The royal urn of King Bhumibol Adulyadej being transported on Golden Palanquin | |||

| Monarch(s) |

| ||

| Leader(s) | |||

| Key events | |||

| Chronology | |||

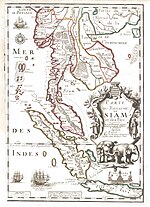

| History of Thailand |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Thailand since 2001 has been dominated by the politics surrounding the rise and fall from power of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, and subsequent conflicts, first between his supporters and opponents, then over the rising military influence in politics. Thaksin and his Thai Rak Thai Party came to power in 2001 and became very popular among the electorate, especially rural voters. Opponents, however, criticized his authoritarian style and accused him of corruption. Thaksin was deposed in a coup d'état in 2006, and Thailand became embroiled in continuing rounds of political crisis involving elections won by Thaksin's supporters, massive anti-government protests by multiple factions, removals of prime ministers and disbanding of political parties by the judiciary, and two military coups.

Thaksin was prime minister from 2001 to 2006, when he was ousted by a coup following protests by the anti-Thaksin People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD, "Yellow Shirts"). However, his supporters were brought back to power in a new election following the enactment of new constitution in 2007. The PAD protested against the government through most of 2008, and the ruling party was dissolved by the Constitutional Court. The opposition Democrat Party, led by Abhisit Vejjajiva, formed a government, but also faced protests by the opposing Red Shirt movement led by the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship. This led to a violent military crackdown in May 2010. Another Thaksin-aligned party won the election in 2011, installing his sister Yingluck Shinawatra as prime minister. Renewed anti-government protests began in November 2013, and continued until the military again staged a coup in May 2014. Coup leader Prayut Chan-o-cha took power as prime minister, and oversaw systemic suppression of political freedom before finally allowing elections in 2019 under a pro-military constitution, which reinstalled Prayut as prime minister.

The conflicts have sharply divided popular opinion in Thailand. Even in exile, Thaksin still commanded strong support, especially among the rural population of the North and Northeast, who widely benefited from his policies and formed the majority of the electorate. They were joined, especially after the 2006 coup, by liberal academics and activists, who opposed his opponents' pushes to achieve a non-elected government. On the other hand, Thaksin's opponents consisted of much of Bangkok's urban middle class and the Southern population (a traditional Democrat stronghold), professionals and academics, as well as members of the "old elite" who wielded political influence before Thaksin came to power. They claim that Thaksin abused his power and undermined democratic processes and institutional checks and balances, monopolizing power and using populist policies to secure his political standing. While Thaksin's opponents claim that elections which resulted in victories for his allies were not truly democratic because of such interference, his supporters have also accused the courts, which brought down multiple Thaksin-aligned governments, of engaging in judicial activism. Thaksin's influence began to wane following the 2019 election, which separately saw the rise of a progressive youth-oriented movement directed against military interference in politics.

These events took place as the country approached the end of King Bhumibol Adulyadej's reign. The King, who had reigned for 70 years, died in October 2016 after several years of deteriorating health during which he appeared less and less frequently in public. Bhumibol had long been regarded as a uniting figure and guiding moral authority for the country, and commanded a great amount of respect, unlike his successor Vajiralongkorn. The uncertainties surrounding the impending royal succession compounded the political instability. Many anti-Thaksin groups claimed to be loyal to Bhumibol, accusing their opponents of bearing republican sentiments. Prosecutions under the lèse-majesté law sharply increased after 2006, in what has been criticized as politicization of the law at the expense of human rights. Meanwhile, the long-standing separatist movement in the deep South has significantly worsened since 2004, with almost 7,000 having been killed in the conflict.

Economically, the country made its recovery from the 1997 Asian financial crisis and became an upper-middle income economy in 2011, though it was affected by the Great Recession and GDP growth has slowed from the early 2000s. Unlikely the SARS outbreak in 2003, the multiple political crises and coups had little impact on the Thai economy individually, and the country quickly recovered from major disasters, such as Boxing Day tsunami in Southern Thailand in December 2004 and with widespread flooding in 2011. However, inequality remains high, contributing to the urban–rural divide and potentially fuelling further social and political conflict. The future of the country remains unclear as the 2017 constitution, drafted under junta, paved the way for further military intervention in politics, amidst concerns regarding the return to democratic rule and the changing role of the monarchy under a new reign.

On 13 January 2020, Thailand was the first country to report a case of the global novel coronavirus outside China. In March, Thailand entered lockdowns, which saw the beginning of stay-at-home orders, mask mandates, and social distancing. While it was relatively successful in containing the virus, the country saw many social and economic impacts from the pandemic, its tourism-dependent economy being badly affected. Two years later, the COVID-19 response in the country was ended.

Politics

[edit]Premiership of Thaksin Shinawatra

[edit]

Thaksin's Thai Rak Thai Party came to power through a general election in 2001, where it won a near-majority in the House of Representatives. As prime minister, Thaksin launched a platform of policies, popularly dubbed "Thaksinomics", which focused on promoting domestic consumption and providing capital especially to the rural populace. By delivering on electoral promises, including populist policies such as the One Tambon One Product project and the 30-baht universal healthcare scheme, his government enjoyed high approval, especially as the economy recovered from the effects of the 1997 Asian financial crisis. Thaksin became the first democratically elected prime minister to complete a four-year term in office, and Thai Rak Thai won a landslide victory in the 2005 general election.[1]

However, Thaksin's rule was also marked by controversy. He had adopted an authoritarian "CEO-style" approach in governing, centralising power and increasing intervention in the bureaucracy's operations. While the 1997 constitution had provided for greater government stability, Thaksin also used his influence to neutralise the independent bodies designed to serve as checks and balances against the government. He threatened critics and manipulated the media into carrying only positive commentary. Human rights in general deteriorated, with a "war on drugs" resulting in over 2,000 extrajudicial killings. Thaksin responded to the South Thailand insurgency with a highly confrontational approach, resulting in marked increases in violence.[2]

Public opposition to Thaksin's government gained much momentum in January 2006, sparked by the sale of Thaksin's family's holdings in Shin Corporation to Temasek Holdings. A group known as the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD), led by media proprietor Sondhi Limthongkul, began holding regular mass rallies, accusing Thaksin of corruption. As the country slid into a state of political crisis, Thaksin dissolved the House of Representatives, and a general election was held in April. However, opposition parties, led by the Democrat Party, boycotted the election. The PAD continued its protests, and although Thai Rak Thai won the election, the results were nullified by the Constitutional Court due to a change in arrangement of voting booths. A new election was scheduled for October, and Thaksin continued to serve as head of the caretaker government as the country celebrated King Bhumibol's diamond jubilee on 9 June 2006.[3]

2006 coup d'état

[edit]

On 19 September 2006, the Royal Thai Army under General Sonthi Boonyaratglin staged a bloodless coup d'état and overthrew the caretaker government. The coup was widely welcomed by the anti-Thaksin protesters, and the PAD dissolved itself. The coup leaders established a military junta called the Council for Democratic Reform, later known as the Council for National Security. It annulled the 1997 constitution, promulgated an interim constitution and appointed an interim government with former army commander General Surayud Chulanont as prime minister.[4] It also appointed a National Legislative Assembly to serve the functions of parliament and a Constitution Drafting Assembly to create a new constitution. The new constitution was promulgated in August 2007 following a referendum.[5]

As the new constitution came into effect, a general election was held in December 2007. Thai Rak Thai and two coalition parties had earlier been dissolved as a result of a ruling in May by the junta-appointed Constitutional Tribunal, which found them guilty of election fraud, and their party executives were barred from politics for five years. Thai Rak Thai's former members regrouped and contested the election as the People's Power Party (PPP), with veteran politician Samak Sundaravej as party leader. The PPP courted the votes of Thaksin's supporters, won the election with a near-majority, and formed government with Samak as prime minister.[5]

2008 political crisis

[edit]

Samak's government actively sought to amend the 2007 Constitution, and as a result the PAD regrouped in May 2008 to stage further anti-government demonstrations. The PAD accused the government of trying to grant amnesty to Thaksin, who was facing corruption charges. It also raised issues with the government's support of Cambodia's submission of Preah Vihear Temple for World Heritage Site status. This led to an inflammation of the border dispute with Cambodia, which later resulted in multiple casualties. In August, the PAD escalated its protest and invaded and occupied the Government House, forcing government officials to relocate to temporary offices and returning the country to a state of political crisis. Meanwhile, the Constitutional Court found Samak guilty of conflict of interest due to his working for a cooking TV programme, terminating his premiership in September. Parliament then chose PPP deputy leader Somchai Wongsawat to be the new prime minister. Somchai is a brother-in-law of Thaksin's, and the PAD rejected his selection and continued its protests.[6]

Living in exile since the coup, Thaksin returned to Thailand only in February 2008 after the PPP had come to power. In August, however, amid the PAD protests and his and his wife's court trials, Thaksin and his wife, Potjaman, jumped bail and applied for asylum in the United Kingdom, which was denied. He was later found guilty of abuse of power in helping Potjaman buy land on Ratchadaphisek Road, and in October was sentenced in absentia by the Supreme Court to two years in prison.[7]

The PAD further escalated its protest in November, forcing the closure of both of Bangkok's international airports. Shortly after, on 2 December, the Constitutional Court dissolved the PPP and two other coalition parties for electoral fraud, ending Somchai's premiership.[8] The opposition Democrat Party then formed a new coalition government, with Abhisit Vejjajiva as prime minister.[9]

Abhisit government and 2010 protests

[edit]Abhisit presided over a six-party coalition government, which was formed through the support of Newin Chidchob and his Friends of Newin Group, who had broken away from the previous PPP-led coalition. By then, Thailand's economy was feeling the effects of the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the ensuing Great Recession. Abhisit responded to the crisis with various stimulus programmes, while also expanding on some of the populist policies initiated by Thaksin.[10]

Relatively early in Abhisit's premiership, the pro-Thaksin group the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) began staging anti-government protests. The UDD, also known as the "Red Shirts" in contrast with the PAD's yellow, was formed following the 2006 coup and had previously protested against the military government and staged counter-rallies against the PAD in 2008. In April 2009, the UDD staged protests in Pattaya, where they disrupted the fourth East Asia Summit, and also in Bangkok, leading to clashes with government forces.[11]

The UDD suspended most of their political activities throughout the rest of the year, but regathered in March 2010 to call for new elections. The protesters later occupied a large area of Bangkok's central shopping district, blocking off areas from Ratchaprasong Intersection to Lumphini Park. Violent attacks, both against protesters and government units, escalated as the situation dragged on, while negotiations between the government and the protest leaders repeatedly failed. Around mid-May, in an attempt to remove the protesters, military forces performed a crackdown on the protest, leading to violent confrontations and over ninety deaths. Arson attacks erupted around the protest site as well as several provincial centres, but the government soon took control of the situation. The protesters dispersed as UDD leaders surrendered.[12]

Yingluck government and 2013–2014 crisis

[edit]

Abhisit dissolved the House of Representatives the following year, and a general election was held on 3 July 2011. It was won by the Thaksin-aligned Pheu Thai Party (created to replace the PPP in 2008), and Yingluck Shinawatra, a younger sister of Thaksin's, became prime minister.[13] Although the government initially struggled in its response to the widespread flooding in 2011, the political scene remained mostly calm throughout 2012 and early 2013.

Continuing on the populist platform, Yingluck's government delivered on election promises, including a controversial rice-pledging scheme, which was later found to have lost the government hundreds of billions of baht. However, it was the government's push to pass an amnesty bill and amend the constitution in 2013 that sparked public outcry. Protesters, whose leadership would later call itself the People's Democratic Reform Committee, demonstrated against the bill, which they perceived as being created to grant amnesty to Thaksin. Although the bill was voted down by the Senate, the protests turned towards an anti-government agenda, and the protesters moved to occupy several government offices, as well as the central shopping district, in a bid to create a "People's Council" to oversee reforms and remove Thaksin's political influence.[14]

Yingluck responded to the protests by dissolving the House of Representatives, and a general election was held on 2 February 2014. The protesters moved to obstruct the election, forcing voting to be postponed at some polling stations. This later became the basis of the Constitutional Court's annulment of the election, since according to the constitution, it had to take place in one day.[15] This left the country still without a working government, amid increasing violent attacks by unnamed factions.

As the political stalemate continued, the Constitutional Court on 7 May ruled on a case concerning the transfer of Thawil Pliensri from his post as Secretary-general of the National Security Council back in 2011. It found that this was done with conflict of interest, and ruled that Yingluck be removed from her role as caretaker prime minister, along with nine other cabinet members. Deputy Prime Minister Niwatthamrong Boonsongpaisan was chosen to replace Yingluck as caretaker prime minister.[16]

2014 coup d'état

[edit]

Amid the ongoing political crisis, the Royal Thai Army under General Prayut Chan-o-cha declared martial law on 20 May 2014, citing the need to suppress violence and maintain peace and order. Talks were held between leaders of various factions, but after these failed, Prayut took power in a coup d'état on 22 May. The National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) was established as the ruling junta, and the constitution was again repealed.[17]

In contrast to the 2006 coup, the NCPO oversaw a more systemic suppression of opposition. Politicians and activists, as well as academics and journalists, were summoned; some were detained for "attitude adjustment". An interim constitution was eventually promulgated on 22 July, followed by the creation of an appointed National Legislative Assembly, and the appointment of Prayut as prime minister on 25 August. Despite promising a road map for the return to democracy, the junta exercised considerable authoritarian power; political activities, especially criticism of the military, were banned, and the lèse-majesté law was even more heavily enforced than before.[18] After several drafts, a new constitution was passed in a referendum on 7 August 2016. It contained many provisions that allowed the military to assert its influence in politics. After repeated postponements, elections took place on 24 March 2019.[19]

2019 parliament and 2020 protests

[edit]This section should include only a brief summary of 2020 Thai protests. |

Several new parties emerged to contest the 2019 election, including the pro-Prayut Palang Pracharath Party, and the liberal, anti-junta Future Forward Party led by Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit. The constitution's provision that also included the junta-appointed Senate in the parliamentary vote for prime minister led to the Palang Pracharath–led coalition successfully installing Prayut as prime minister in June.[20] Meanwhile, Future Forward, which had found success mobilizing support from young people and became the most vocal among the opposition, found itself the target of technicality-based petitions, and the Constitutional Court ruled in February 2020 that a loan the party received from Thanathorn was illegal, dissolving the party.[21]

The ruling was met by student protests in university campuses all over the country, which subsided due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The protests resumed in July and developed into a sustained movement against the military-dominated government and human rights violations, with several large demonstrations, some of which also included public criticisms of the monarchy.[22] Several protest groups emerged, most prominently the Free People group, who demanded the resignation of the cabinet, dissolution of parliament, and drafting of a new constitution.[23]

On 3 August, two student groups publicly raised demands to reform the monarchy, breaking a long taboo of publicly criticising the monarchy. A week later, ten demands for monarchy reform were declared. A 19 September rally saw 20,000–100,000 protesters and has been described as an open challenge to King Vajiralongkorn. A government decision to delay voting on a constitutional amendment in late September fuelled nearly unprecedented public republican sentiment.[24] Following mass protests on 14 October, a "severe" state of emergency was declared in Bangkok during 15–22 October, citing the alleged blocking of a royal motorcade. Emergency powers were extended to the authorities on top of those already given by the Emergency Decree since March. Protests continued despite the ban, prompting a crackdown by police on 16 October using water cannons.

In November, the Parliament voted to pass two constitutional amendment bills, but their content effectively shut down the protesters' demands of abolishing the Senate and reformation of the monarchy. Clashes between the protesters and the police and royalists became more prevalent, and resulted in many injuries. The protesters were mostly students and young people without an overall leader.[25] Apart from the aforementioned political demands, some rallies were held by LGBTQ groups who called for gender equality, as well as student groups who campaigned for reforming the country's education system.

Government responses included filing criminal charges using the Emergency Decree; arbitrary detention and police intimidation; delaying tactics; the deployment of military information warfare units; media censorship; the mobilisation of pro-government and royalist groups who have accused the protesters of receiving support from foreign governments or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) as part of a global conspiracy against Thailand; and the deployment of thousands of police at protests. The government ordered university chancellors to prevent students from demanding reforms to the monarchy and to identify student protest leaders. Protests since October, when the King had returned to the country from Germany,[26] resulted in the deployment of the military, riot police, and mass arrests.

In November 2021, The Constitutional Court ruled that demands for reform of the Thai monarchy abused the rights and freedoms and harmed the state’s security and ordered an end to all movements, declaring them unconstitutional. It has been likened to judicial coup.[27]

In September 2022, Thailand's Constitutional Court ruled that Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha could stay in office. The opposition had challenged him, because the new constitution limits the term for prime minister as a total period of eight years in office. The Constitutional Court's ruling was that his term in office began in April 2017, simultaneously with the new constitution, although Prayut had ruled as the leader of the government since the 2014 military coup.[28]

2023 election and Srettha government

[edit]In May 2023, Thailand’s reformist opposition, the progressive Move Forward Party (MFP) and the populist Pheu Thai Party, won the general election, meaning the royalist-military parties that supported Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha lost power.[29] Initially, the opposition parties attempted to form a government together with MFP's Pita Limjaroenrat as prime ministerial candidate. This failed despite a majority in the lower house, as under the 2017 constitution the junta-appointed Senate also voted for the prime minister along with the elected lower house.[30] Pheu Thai then dissolved its coalition with MFP and allied instead with the royalist-military parties, which allowed the new coalition to garner votes in the military-dominated Senate. On 22 August 2023, its candidate Srettha Thavisin became Thailand’s new prime minister, while the Pheu Thai party’s billionaire figurehead Thaksin Shinawatra returned to Thailand after years in self-imposed exile.[31]

Royal succession

[edit]

Throughout most of the 2010s, King Bhumibol Adulyadej underwent a period of deteriorating health, being repeatedly hospitalized and making few public appearances. The King died on 13 October 2016, prompting an outpouring of grief among the people and a year of national mourning. The King had reigned since 1946, and was regarded as a moral authority and a pillar of stability for the nation. He was succeeded by his son, Vajiralongkorn, who, in a break with tradition, delayed his formal accession until 1 December 2016.[32] King Bhumibol's royal cremation ceremony was held on 26 October 2017, with over 19 million people attending sandalwood flower-laying ceremonies throughout the country.[33] The coronation of King Vajiralongkorn was held on 4 May 2019.[34]

Conflicts

[edit]In the three southernmost Muslim-majority provinces, a long-standing separatist movement flared up in 2004, during Thaksin's premiership. Thaksin's heavy-handed responses escalated the violence, which entailed frequent bombings and attacks on security forces as well as civilians. Almost 7,000 people are estimated to have died. The government held peace talks in 2013, which were unsuccessful. Though the violence has declined since its peak in 2010, sporadic attacks still occur, with little sign of resolution.[35]

Thailand has also seen several terrorist attacks outside of the South, the most significant being a bombing in Bangkok in 2015, which killed 20 and injured over 120. The bombing is suspected to be the work of Uyghur nationalists retaliating against Thailand's earlier repatriation of Uyghur asylum-seekers to China, though the case has not been conclusively settled.[36] Other (unrelated) attacks have also occurred in Bangkok in 2006 and 2012.

Disasters

[edit]

Thailand saw some of its worst natural disasters during this period. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami caused over 5,000 deaths,[37] while the 2011 floods resulted in economic losses estimated at 1.43 trillion baht (US$46 billion).[38]

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]In the light of COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand was one of the first countries affected by the global outbreak in 2020, and by March, all provinces declared state of emergency; while it was relatively successful in containing the virus, its tourism-dependent economy was badly affected. In 2022, two years later, the COVID-19 response in Thailand was ended due to the virus likely becoming endemic.

Economy and society

[edit]Thailand made its recovery from the 1997 Asian financial crisis, completing repayment of loans from the IMF in 2003.[39] The World Bank re-classified Thailand as an upper-middle income economy in 2011.[40] However, the level of economic disparity remains high, even as absolute poverty levels have continued to decline. A number of government policies have successfully provided a social safety net for the large majority of the population, including a universal healthcare system and free access to primary and secondary education.[41]

The successes of Thaksin's policies have coincided with an increased political awareness among the rural populace, who benefited from them. Following Thaksin's removal, they took on an active political role, and became competing forces with the urban middle class in the subsequent political crises. Thai society has thus become highly polarized along political lines, which for the most part reflected the socioeconomic divide.[42] While military rule since the 2014 coup has for the most part suppressed overt conflict, there is uncertainty over the expected eventual return to democratic rule.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 262–5

- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 263–8

- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 269–70

- ^ "Thailand prime minister sworn in". 1 October 2006.

- ^ a b Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 270–2

- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 272–3

- ^ MacKinnon, Ian (21 October 2008). "Former Thai PM Thaksin found guilty of corruption". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Top Thai court ousts PM Somchai". BBC News. 2 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Bell, Thomas (15 December 2008). "Old Etonian becomes Thailand's new prime minister". The Telegraph. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Ahuja, Ambika (28 September 2010). "Analysis: Thailand struggles against tide of corruption". Reuters. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 274–5

- ^ Baker & Phongpaichit 2014, pp. 275–7

- ^ Szep, Jason; Petty, Martin (3 July 2011). "Thaksin party wins Thai election by a landslide". Reuters. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Hodal, Kate (13 January 2014). "Thai protesters blockade roads in Bangkok for 'shutdown'". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Olarn, Kocha; Mullen, Jethro; Cullinane, Susannah (21 March 2014). "Thai court declares February election invalid". CNN. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Hodal, Kate (7 May 2014). "Thai court orders Yingluck Shinawatra to step down as PM". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (22 May 2014). "Thailand's Military Stages Coup, Thwarting Populist Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Gerson, Katherine (2 June 2018). "Thai Junta Shows No Signs of Halting Assault on Human Rights". The Diplomat. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Thailand's military junta gets its way in a rigged vote". The Economist. 24 March 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "House, Senate elect Prayut Thailand's new prime minister". Bangkok Post. 6 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Vejpongsa, Tassanee; Peck, Grant (26 February 2020). "Thai student rallies protest dissolution of opposition party". Washington Post. AP. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ "The students risking it all to challenge the monarchy". BBC News. 14 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Mala, Dumrongkiat (17 August 2020). "Students press demands". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Jory, Patrick (31 December 2019). "Chapter Five. Republicanism in Thai History". In Peleggi, Maurizio (ed.). A Sarong for Clio. Cornell University Press. pp. 97–118. doi:10.7591/9781501725937-007. ISBN 978-1-5017-2593-7. S2CID 198887226. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ^ "Explainer: What's behind Thailand's protests?". Reuters. 15 October 2020. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ Bengali, Shashank; Kirschbaum, Erik (16 October 2020). "A royal bubble bursts: Thailand's king faces trouble on two continents". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020.

- ^ "Thai court rules calls for curbs on monarchy are 'abuse of freedoms'". the Guardian. 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Prayuth Chan-ocha: Thai court rules coup leader can remain PM". BBC News. 30 September 2022.

- ^ Rasheed, Zaheena. "'Impressive victory': Thai opposition crushes military parties". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca; Siradapuvadol, Navaon (2023-07-13). "Thailand's winning candidate for PM blocked from power". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-09-14.

- ^ "Srettha Thavisin elected Thailand PM as Thaksin returns from exile". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Thai crown prince proclaimed new king". BBC News. 1 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Olarn and, Kocha; Cripps, Karla (27 October 2017). "Thailand's royal cremation ceremony caps year of mourning". CNN. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Thailand's King Vajiralongkorn crowned". BBC News. 3 May 2019.

- ^ Morch, Maximillian (6 February 2018). "The Slow Burning Insurgency in Thailand's Deep South". The Diplomat. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas; Wong, Edward (15 September 2015). "Thailand Blames Uighur Militants for Bombing at Bangkok Shrine". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Fatalities in 2004 tsunami remembered". The Nation. 26 December 2011. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "The World Bank Supports Thailand's Post-Floods Recovery Effort". World Bank. 13 December 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Thailand Repays IMF Loan 2 Years Ahead of Schedule". VOA. 1 August 2003. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Thailand Now an Upper Middle Income Economy". World Bank (Press release). 2 August 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ "Thailand Overview". World Bank. September 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (30 June 2011). "Rural Thais Find an Unaccustomed Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 December 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2014). A History of Thailand (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107420212.

Further reading

[edit]- Chachavalpongpun, Pavin, ed. (2014). Good Coup Gone Bad : Thailand's political developments since Thaksin's downfall. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4459-60-0.

- Ferrara, Federico (2015). The Political Development of Modern Thailand. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107061811.

- Phongpaichit, Pasuk; Baker, Chris (2004). Thaksin : The business of politics in Thailand. NIAS Press. ISBN 9788791114786.