Lee Marvin

Lee Marvin | |

|---|---|

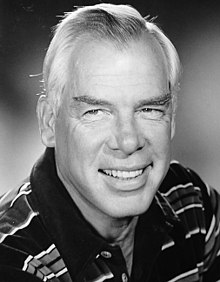

Marvin in 1971 | |

| Born | February 19, 1924 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | August 29, 1987 (aged 63) Tucson, Arizona, U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Education | Manumit School St. Leo College Preparatory School |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1948–1986 |

| Spouse(s) |

Betty Ebeling

(m. 1951; div. 1967)Pamela Feeley

(m. 1970; "his death" is deprecated; use "died" instead. 1987) |

| Partner | Michelle Triola (1965–1970) |

| Children | 4 |

Lee Marvin (February 19, 1924 – August 29, 1987) was an American film and television actor.

Known for his distinctive voice and premature white hair, Marvin initially appeared in supporting roles, mostly villains, soldiers, and other hardboiled characters. A prominent television role was that of Detective Lieutenant Frank Ballinger in the crime series M Squad (1957–1960). Marvin is best remembered for his lead roles as "tough guy" characters such as Charlie Strom in The Killers (1964), Rico Fardan in The Professionals (1966), Major John Reisman in The Dirty Dozen, Walker in Point Blank (both 1967), and the Sergeant in The Big Red One (1980).

One of Marvin's more notable movie projects was Cat Ballou (1965), a comedy Western in which he played dual roles. For portraying both gunfighter Kid Shelleen and criminal Tim Strawn, he won the Academy Award for Best Actor, along with a BAFTA Award, a Golden Globe Award, an NBR Award, and the Silver Bear for Best Actor.

Early life

Lee Marvin was born in New York City to Lamont Waltman Marvin, an advertising executive, and Courtenay Washington (née Davidge), a fashion writer. As with his elder brother, Robert (1922–1999), he was named in honor of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, who was his first cousin, four times removed.[1][2] His father was a direct descendant of Matthew Marvin Sr., who emigrated from Great Bentley, Essex, England in 1635, and helped found Hartford, Connecticut. Marvin studied violin when he was young.[3] As a teenager, Marvin "spent weekends and spare time hunting deer, puma, wild turkey, and bobwhite in the wilds of the then-uncharted Everglades".[4]

He attended Manumit School, a Christian socialist boarding school in Pawling, New York, during the late 1930s, and later attended St. Leo College Preparatory School, a Catholic school in St. Leo, Florida after being expelled from several other schools for bad behavior.[5]

Military service

World War II

Marvin left school at 18 to enlist in the United States Marine Corps Reserve on August 12, 1942. He served with the 4th Marine Division in the Pacific Theater during World War II.[6] While serving as a member of "I" Company, 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines, 4th Marine Division, he was wounded in action on June 18, 1944, during the assault on Mount Tapochau in the Battle of Saipan, during which most of his company were casualties.[7] He was hit by machine gun fire, which severed his sciatic nerve,[8] and then was hit again in the foot by a sniper.[9] After over a year of medical treatment in naval hospitals, Marvin was given a medical discharge with the rank of private first class. He previously held the rank of corporal, but had been demoted for troublemaking.[9]

Marvin's military awards include the Purple Heart Medal, the Presidential Unit Citation, the American Campaign Medal, the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, and the Combat Action Ribbon.[10]

Medals and ribbons

| Navy Commendation Medal with V Device |

Acting career

Early acting career

After the war, while working as a plumber's assistant at a local community theatre in upstate New York, Marvin was asked to replace an actor who had fallen ill during rehearsals. He caught the acting bug and got a job with the company at $7 a week. He moved to Greenwich Village and used the G.I. Bill to study at the American Theatre Wing.[11][12]

He appeared on stage in a production of Uniform of Flesh, an adaptation of Billy Budd (1949).[13] It was done at the Experimental Theatre, where a few months later Marvin also appeared in The Nineteenth Hole of Europe (1949).[14]

Marvin began appearing on television shows like Escape, The Big Story, and Treasury Men in Action.[15]

He made it to Broadway with a small role in a production of Uniform of Flesh, now titled Billy Budd in February 1951.[16]

Hollywood

Marvin's film debut was in You're in the Navy Now (1951), directed by Henry Hathaway, a movie that marked the debuts of Charles Bronson and Jack Warden. This required some filming in Hollywood. Marvin decided to stay in California.[11]

He had a similar small part in Teresa (1951) directed by Fred Zinnemann. As a decorated combat veteran, Marvin was a natural in war dramas, where he frequently assisted the director and other actors in realistically portraying infantry movement, arranging costumes, and the use of firearms.

He guest starred on episodes of Fireside Theatre, Suspense and Rebound. Hathaway used him again on Diplomatic Courier (1952) and he could be seen in Down Among the Sheltering Palms (1952), directed by Edmund Goulding, We're Not Married! (1952), also for Goulding, The Duel at Silver Creek (1952) directed by Don Siegel, and Hangman's Knot (1952), directed by Roy Huggins.

He guest starred on Biff Baker, U.S.A. and Dragnet, and had a decent role in a feature with Eight Iron Men (1952), a war film produced by Stanley Kramer (Marvin's role had been played on Broadway by Burt Lancaster).[17]

He was a sergeant in Seminole (1953), a Western directed by Budd Boetticher, and was a corporal in The Glory Brigade (1953), a Korean War film.[18]

Marvin guest starred in The Doctor, The Revlon Mirror Theater , Suspense again and The Motorola Television Hour.

He was now in much demand for Westerns: The Stranger Wore a Gun (1953) with Randolph Scott, and Gun Fury (1953) with Rock Hudson.

The Big Heat and The Wild One

Marvin received much acclaim for his portrayal as villains in two films: The Big Heat (1953) where he played Gloria Grahame's vicious boyfriend, directed by Fritz Lang; and The Wild One (1953) opposite Marlon Brando (Marvin's gang in the film was named "The Beetles"), produced by Kramer.[19]

He continued in TV shows such as The Plymouth Playhouse and The Pepsi-Cola Playhouse. He had support roles in Gorilla at Large (1954) and had a notable small role as smart-aleck sailor Meatball in The Caine Mutiny (1954), produced by Kramer.[11]

Marvin was in The Raid (1954), Center Stage, Medic and TV Reader's Digest.[20]

He had an excellent part as Hector, the small-town hood in Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) with Spencer Tracy.[21] Also in 1955, he played a conflicted, brutal bank-robber in Violent Saturday. A latter-day critic wrote of the character, "Marvin brings a multi-faceted complexity to the role and gives a great example of the early promise that launched his long and successful career."[22]

Marvin played Robert Mitchum's friend in Not as a Stranger (1955), a medical drama produced by Kramer. He had good supporting roles in A Life in the Balance (1955) (he was third billed), and Pete Kelly's Blues (1955) and appeared on TV in Jane Wyman Presents The Fireside Theatre and Studio One in Hollywood.

Marvin was in I Died a Thousand Times (1955) with Jack Palance, Shack Out on 101 (1955), Kraft Theatre, and Front Row Center.

Marvin was the villain in 7 Men from Now (1956) with Randolph Scott directed by Boetticher. He was second-billed to Palance in Attack (1956) directed by Robert Aldrich.

Marvin had good roles in Pillars of the Sky (1956) with Jeff Chandler, The Rack (1956) with Paul Newman, Raintree County (1956) and The Missouri Traveler (1958). He also guest starred on Climax! (several times), Studio 57, The United States Steel Hour and Schlitz Playhouse.

M Squad

Marvin finally got to be a leading man in M Squad as Chicago cop Frank Ballinger in 100 episodes of the successful 1957–1960 television series. One critic described the show as "a hyped-up, violent Dragnet ... with a hard-as-nails Marvin" playing a tough police lieutenant. Marvin received the role after guest-starring in a Dragnet episode as a serial killer.[23]

When the series ended Marvin appeared on Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, Sunday Showcase, The Barbara Stanwyck Show, The Americans, Wagon Train, Checkmate, General Electric Theater, Alcoa Premiere, The Investigators, Route 66 (he was injured during a fight scene),[24] Ben Casey, Bonanza, The Untouchables (several times), The Virginian, The Twilight Zone ("The Grave" and "Steel"), The Dick Powell Theatre,[25] and The Investigators.[26]

Early 1960s

Marvin returned to feature films with a prominent role in The Comancheros (1961) starring John Wayne. He played in two more films with Wayne, both directed by John Ford: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), and Donovan's Reef (1963). As the vicious Liberty Valance, Marvin played his first title role and held his own with two of the screen's biggest stars (Wayne and James Stewart).[27]

In 1962 Marvin appeared as Martin Kalig on the TV western The Virginian in the episode titled "It Tolls for Thee." He continued to guest star on shows like Combat!, Dr. Kildare and The Great Adventure. He did The Case Against Paul Ryker for Kraft Suspense Theatre.

For director Don Siegel, Marvin appeared in The Killers (1964) playing an efficient professional assassin alongside Clu Gulager, grappling with villain Ronald Reagan and Angie Dickenson. The Killers was the first film in which Marvin received top billing.[28]

He guest starred on Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre.

Cat Ballou and stardom

Marvin finally became a star for his comic role in the offbeat Western Cat Ballou (1965) starring Jane Fonda. This was a surprise hit and Marvin won the Academy Award for Best Actor. He also won the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the 15th Berlin International Film Festival in 1965.[29]

Playing alongside Vivien Leigh and Simone Signoret, Marvin won the 1966 National Board of Review Award for male actors for his role in Ship of Fools (1965) directed by Kramer.[N 1][33]

Marvin next performed in the Western The Professionals (1966), in which he played the leader of a small band of skilled mercenaries (Burt Lancaster, Robert Ryan, and Woody Strode) rescuing a kidnap victim (Claudia Cardinale) shortly after the Mexican Revolution.[34][35]

He followed that film with the hugely successful World War II epic The Dirty Dozen (1967) in which top-billed Marvin again portrayed an intrepid commander of a colorful group (played by John Cassavetes, Charles Bronson, Telly Savalas, Jim Brown, and Donald Sutherland) performing an almost impossible mission. Robert Aldrich directed.[36]

In the wake of these two films and after having received his Oscar, Marvin was a huge star, given enormous control over his next film Point Blank. In Point Blank, an influential film for director John Boorman, he portrayed a hard-nosed criminal bent on revenge. Marvin, who had selected Boorman for the director's slot, had a central role in the film's development, plot, and staging.[25]

In 1968, Marvin also appeared in another Boorman film, the critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful World War II character study Hell in the Pacific, also starring famed Japanese actor Toshiro Mifune. Boorman recounted his work with Lee Marvin on these two films and Marvin's influence on his career in the 1998 documentary Lee Marvin: A Personal Portrait by John Boorman. Paul Ryker, which Marvin shot for TV in 1963 was released theatrically as Sergeant Ryker.[37]

Marvin was originally cast as Pike Bishop (later played by William Holden) in The Wild Bunch (1969), but fell out with director Sam Peckinpah and pulled out to star in the Western musical Paint Your Wagon (1969), in which he was top-billed over a singing Clint Eastwood. Despite his limited singing ability, he had a hit with the song "Wand'rin' Star". By this time, he was getting paid $1 million per film, $200,000 less than top star Paul Newman was making at the time, yet he was ambivalent about the movie business, even with its financial rewards:[3]

You spend the first forty years of your life trying to get in this business, and the next forty years trying to get out. And then when you're making the bread, who needs it?

1970s

Marvin had a much greater variety of roles in the 1970s, with fewer 'bad-guy' roles than in earlier years. His 1970s movies included Monte Walsh (1970), a Western with Palance and Jeanne Moreau; the violent Prime Cut (1972) with Gene Hackman; Pocket Money (1972) with Paul Newman, for Stuart Rosenberg; Emperor of the North (1973) opposite Ernest Borgnine for Aldrich; as Hickey in The Iceman Cometh (1973) with Fredric March and Robert Ryan, for John Frankenheimer; The Spikes Gang (1974) with Noah Beery Jr. for Richard Fleischer; The Klansman (1974) with Richard Burton; Shout at the Devil (1976), a World War I adventure with Roger Moore, directed by Peter Hunt; The Great Scout & Cathouse Thursday (1976), a comic Western with Oliver Reed; and Avalanche Express (1978), a Cold War thriller with Robert Shaw who died during production. None of these films were big box-office hits.[38][39]

Marvin was offered the role of Quint in Jaws (1975) but declined, stating "What would I tell my fishing friends who'd see me come off a hero against a dummy shark?"[40]

1980s

Marvin's last big role was in Samuel Fuller's The Big Red One (1980), a war film based on Fuller's own war experiences.[41]

His remaining films were Death Hunt (1981), a Canadian action movie with Charles Bronson, directed by Hunt; Gorky Park (1983) with William Hurt; and Dog Day (1984), shot in France.[25]

For TV he did The Dirty Dozen: Next Mission (1985; a sequel with Marvin, Ernest Borgnine, and Richard Jaeckel picking up where they had left off despite being 18 years older).

His final appearance was in The Delta Force (1986) with Chuck Norris, playing a role turned down by Charles Bronson.[42][43]

Personal life

Marvin was a Democrat who opposed the Vietnam War. He publicly endorsed John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election.[28]

Marriages, children and partners

Marvin married Betty Ebeling in February 1951 and together they had four children, son Christopher Lamont (1952–2013),[44] and three daughters: Courtenay Lee (b. 1954), Cynthia Louise (b. 1956), and Claudia Leslie (1958–2012).[45][46] Married 16 years, they divorced in 1967.[47]

Marvin reunited with his high school sweetheart, Pamela Feeley, following his divorce. They married in October 1970. She had four children with three previous marriages; they had no children together and remained married until his death in 1987.[48]

Community property case

- See also Marvin v. Marvin

In 1971, Marvin was sued by Michelle Triola, his live-in girlfriend from 1965 to 1970, who legally changed her surname to "Marvin".[3] Although the couple never married, she sought financial compensation similar to that available to spouses under California's alimony and community property laws. Triola claimed Marvin made her pregnant three times and paid for two abortions, while one pregnancy ended in miscarriage.[49] She claimed the second abortion left her unable to bear children.[49] The result was the landmark "palimony" case, Marvin v. Marvin, 18 Cal. 3d 660 (1976).[50]

In 1979, Marvin was ordered to pay $104,000 to Triola for "rehabilitation purposes", but the court denied her community property claim for one-half of the $3.6 million which Marvin had earned during their six years of cohabitation – distinguishing nonmarital relationship contracts from marriage, with community property rights only attaching to the latter by operation of law. Rights equivalent to community property only apply in nonmarital relationship contracts when the parties expressly, whether orally or in writing, contract for such rights to operate between them. In August 1981, the California Court of Appeal found that no such contract existed between them and nullified the award she had received.[51][52] Michelle Triola died of lung cancer on October 30, 2009, having been with actor Dick Van Dyke since 1976.[53]

Later there was controversy after Marvin characterized the trial as a "circus", saying "everyone was lying, even I lied". There were official comments about possibly charging Marvin with perjury, but no charges were filed.[54]

This case was used as fodder for a mock debate skit on Saturday Night Live called "Point Counterpoint",[55] and on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson as a skit with Carson as Adam, and Betty White as Eve.[56]

Death

In December 1986, Marvin was hospitalized for more than two weeks because of a condition related to coccidioidomycosis. He went into respiratory distress and was administered steroids to help his breathing. He had major intestinal ruptures as a result, and underwent a colectomy. Marvin died of a heart attack on August 29, 1987, aged 63.[57] He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.[58][59]

Filmography

Film

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Escape | Episode: "Whappernocker Song" | |

| The Big Story | Episode: "Eugene Travis, Memphis Tennessee Reporter" | ||

| Treasury Men in Action | Episode: "The Case of the Deadly Fish" | ||

| 1950–1953 | Suspense | Barrow | 2 episodes |

| 1952 | Rebound | Sgt. Krone / Bull | 2 episodes |

| Fireside Theatre | Episode: "Sound in the Night" | ||

| Biff Baker, U.S.A. | Michler / Captain Hollis | Episode: "Alpine Assignment" | |

| 1952–1953 | Dragnet | James Mitchell / Henry Ross | 2 episodes |

| 1953 | The Doctor | Episode: "The Runaways" | |

| The Revlon Mirror Theater | Red Johnson | Episode: "Lullaby" | |

| The Motorola Television Hour | Episode: "Outlaw's Reckoning" | ||

| Plymouth Playhouse | Episode: "Outlaw's Reckoning" | ||

| 1954 | The Pepsi-Cola Playhouse | John Temple | 2 episodes |

| Center Stage | Zach Toombs | Episode: "The Day Before Atlanta" | |

| Medic | Larry Collins | Episode: "White Is the Color" | |

| 1954–1959 | Schlitz Playhouse of Stars | Jim Patterson / Russ Anderson | 3 episodes |

| 1954–1961 | General Electric Theater | Sid Benton / Clerk / Joe Kittridge / Dick Giles / Art Temple / Captain Morrissey | 7 episodes |

| 1955 | TV Reader's Digest | Charlie Faust | Episode: "How Charlie Faust Won a Pennant for the Giants" |

| Fireside Theatre | Jigger | Episode: "Little Guy" | |

| Studio One | Teale | Episode: "Shakedown Cruise" | |

| 1955–1958 | Climax! | Mannon Tate / 'Little Man' Brush / Charter Plane Pilot / Capt. Cavallero | 4 episodes |

| 1956 | Kraft Television Theatre | Milo Bogardus | Episode: "The Fool Killer" |

| Front Row Center | David Hawken | Episode: "Dinner Date" | |

| 1957 | Studio 57 | Episode: "You Take Ballistics" | |

| The United States Steel Hour | Episode: "Shadow of Evil" | ||

| 1957–1960 | M Squad | Detective Lt. Frank Ballinger / Lt. Frank Ballinger / Barney | 117 episodes |

| 1959 | Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse | Captain David Roberts | Episode: "Man in Orbit" |

| 1960 | NBC Sunday Showcase | Ira Hayes | Episode: "The American" |

| 1960–1961 | Wagon Train | Jud Benedict / Jose Morales | 2 episodes |

| 1961 | Route 66 | John Ryan / Woody Biggs | 2 episodes |

| The Barbara Stanwyck Show | Jud Hollister | Episode: "Confession" | |

| The Americans | Capt. Judd | Episode: "Reconnaissance" | |

| Checkmate | Lee Tabor | Episode: "Jungle Castle" | |

| Alcoa Premiere | Hughes | Episode: "People Need People" Nominated—Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role | |

| The Investigators | "Nostradamus" (Walter Mimms) | Episode: "The Oracle" | |

| 1961–1962 | The Untouchables | Mike Brannon / Victor Rait / Howard Carson / Nick Acropolis | 3 episodes |

| 1961–1963 | The Twilight Zone | Sam "Steel" Kelly / Conny Miller | Episodes: "The Grave" and "Steel" |

| 1962 | Ben Casey | Gerry Bramson | Episode: "A Story to Be Softly Told" |

| Bonanza | Peter Kane | Episode: "The Crucible" | |

| The DuPont Show of the Week | Juan de Nuñez | Episode: "The Richest Man in Bogotá" | |

| The Virginian | Martin Kalig | Episode: "It Tolls for Thee" | |

| 1962–1964 | Dr. Kildare | Buddy Bishop / Dr. Paul Probeck | 2 episodes |

| 1963 | The Dick Powell Show | Finn / Dave Blassingame | 2 episodes |

| Combat! | Sgt. Turk | Episode: "The Bridge at Châlons" | |

| Kraft Suspense Theatre | Sgt. Paul Ryker | 2 episodes | |

| The Great Adventure | Misok Bedrozian | Episode: "Six Wagons to the Sea" | |

| 1963–1964 | Lawbreakers | Himself – Host / Narrator | 35 episodes |

| 1965 | Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Nick Karajanian | Episode: "The Loving Cup" |

| 1985 | The Dirty Dozen: Next Mission | Maj. John Reisman | Television film |

See also

- The Sons of Lee Marvin, a tongue-in-cheek secret society dedicated to Marvin

- Welcome to Night Vale, which features Lee Marvin as an integral piece of its mythology and supporting cast.

References

Notes

- ^ The film proved to be Leigh's last film and her anguished portrayal of a desperate older woman was punctuated by her real-life "battle with demons".[30] Leigh's performance was tinged by paranoia and resulted in outbursts that marred her relationship with other actors, although both Simone Signoret and Marvin were sympathetic and understanding.[31] In one unusual instance, she hit Marvin so hard with a spiked shoe, it marked his face.[32]

Citations

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 6, 14–15.

- ^ Bailey 2014, p. 270.

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger. "An interview with Lee Marvin." Chicago Sun-Times for Esquire, October 1970.

- ^ "Elk Hunting with Lee Marvin". Gun World. May 1964. Retrieved October 11, 2013.[permanent dead link] .

- ^ Zec 1980, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Wise and Rehill 1999, p. 43.

- ^ Zec 1980, p. 38.

- ^ Rafael, George (February 15, 2007). "The real thing: Marvin and Point Blank". The First Post. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ a b "Hollywood Veterans in Arlington National Cemetery: Lee Marvin". Comet Over Hollywood.

- ^ "PFC Lee Marvin". Together We Served. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ a b c Wilson, Jane (August 27, 1967). "Hanging Tough with Lee Marvin". Los Angeles Times. p. m37.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 67.

- ^ BROOKS ATKINSON (January 31, 1949). "Experimental Theatre Stages Sea Drama Made From One of Herman Melville's Minor Novels". The New York Times. p. 15.

- ^ BROOKS ATKINSON (March 28, 1949). "AT THE THEATRE: Vivian Connell's 'The Nineteenth Hole of Europe' Put on By the Experimental Theatre". The New York Times. p. 16.

- ^ Washburn, Jim (February 21, 1995). "Keepers of the Flame : As fans of Lee Marvin, the members of the BSOL watch his old movies and light up cigars in the late actor's honor--even though they know the tough guy probably wouldn't approve". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ "'BILLY BUDD' MAKES ITS DEBUT TONIGHT: Coxe-Chapman Play Based on Melville Novel Will Arrive at the Biltmore Theatre". The New York Times. February 10, 1951. p. 22.

- ^ "FILMLAND BRIEFS". Los Angeles Times. February 14, 1952. p. A10.

- ^ Lentz 2000, p. 28.

- ^ Schallert, Edwin (January 31, 1953). "David Brian to 'Reform' as Safecracker; More Three-D Work on Foot". Los Angeles Times. p. 9.

- ^ Alpert, Don (February 6, 1966). "Lee Marvin---an Extra Something". Los Angeles Times. p. m4.

- ^ Epstein 2013, pp. 95–96.

- ^ "Film Noir of the Week: Violent Saturday (1955)". www.noiroftheweek.com. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 79.

- ^ "Lee Marvin Is Injured". New York Times. August 16, 1961. p. 63.

- ^ a b c Baker, Bob; Morrison, Patt (August 30, 1987). "Lee Marvin, Menacing Gunman of Films, Dies". Los Angeles Times (Home ed.). p. 1.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "CTVA US Drama - "The Investigators" (1961)". ctva.biz. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 124.

- ^ a b Epstein 2013, p. 135.

- ^ "Berlinale 1965: Prize Winners". Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin. Retrieved: October 11, 2013.

- ^ Bean 2013, p. 155.

- ^ David 1995, p. 46.

- ^ Walker 1987, p. 281.

- ^ Hopper, Hedda (July 11, 1965). "Lee Marvin: Who Needs a Million?". Los Angeles Times. p. A7.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Lentz 2000, p. 109.

- ^ Lentz 2000, p. 110.

- ^ ROGER EBERT (December 15, 1968). "I'm Mean. Tough as Nails. All Those Words". The New York Times. p. D25.

- ^ Dangaard, Colin (June 4, 1978). "Lee Marvin: Still reaching for the stars: Lee Marvin likes tough odds". Chicago Tribune. p. e22.

- ^ Leith, Henrietta (July 7, 1973). "Lee Marvin Cometh to O'Neillr's 'Iceman'". Los Angeles Times. p. b9.

- ^ Zec 1980, p. 217.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (November 14, 2004). "You Had to Be There. Sam Fuller Was". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 202.

- ^ "MARVIN, NORRIS TO COSTAR IN 'THE DELTA FORCE'". Boston Globe. September 3, 1985. p. 27.

- ^ "Obituary: Christopher Marvin The Santa Barbara Independent".

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 256.

- ^ "Obituary: Claudia Leslie Marvin". All-States Cremation. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Epstein 2013, p. 257.

- ^ Marvin 1997, p. 12.

- ^ a b Woo, Elaine (October 31, 2009). "Michelle Triola Marvin dies at 75; her legal fight with ex-lover Lee Marvin added 'palimony' to the language". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ "18 C3d 660: Marvin v. Marvin (1976)." online.ceb.com. Retrieved: October 11, 2013.

- ^ Laskin, Jerry. "California 'Palimony' Law; An Overview." Goldman & Kagon Law Corporation. Retrieved: October 11, 2013.

- ^ "Unmarried Cohabitant's Right to Support and Property". The People's Law Library. January 7, 2001. Archived from the original on September 22, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ " 'Palimony' figure Michelle Triola Marvin dies", Associated Press, October 30, 2009.

- ^ "Lee Marvin". Jango Radio.

- ^ "Point Counterpoint: Lee Marvin & Michelle Triola". Archived 2012-01-16 at the Wayback Machine NBC, March 17, 1979. Retrieved: October 11, 2013.

- ^ "The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson." on YouTube Carson Entertainment Group, February 9, 1979, retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis. "Lee Marvin, Movie Tough Guy, Dies", The New York Times, August 31, 1987; retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ "Lee Marvin to be buried at Arlington". UPI. September 18, 1987. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- ^ "Lee Marvin Is Buried With Military Honors". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 8, 1987. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Mark. Of All the Gin Joints: Stumbling through Hollywood History. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 2014. ISBN 978-1-56512-593-3.

- Bean, Kendra. Vivien Leigh: An Intimate Portrait. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-76245-099-2.

- David, Catherine. Simone Signoret. New York: Overlook Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-87951-581-2.

- Epstein, Dwayne. Lee Marvin: Point Blank. Tucson, Arizona: Schaffner Press, Inc., 2013. ISBN 978-1-93618-240-4.

- Lentz, Robert J. Lee Marvin: His Films and Career. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-7864-0723-9.

- Marvin, Pamela. Lee: A Romance. London: Faber & Faber Limited, 1997. ISBN 978-0-571-19028-7.

- Walker, Alexander. Vivien: The Life of Vivien Leigh. New York: Grove Press, 1987. ISBN 0-8021-3259-6.

- Wise, James E. and Anne Collier Rehill. Stars in the Corps: Movie Actors in the United States Marines. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1-55750-949-9.

- Zec, Donald. Marvin: The Story of Lee Marvin. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1980. ISBN 0-312-51780-7.

External links

- Lee Marvin at IMDb

- Lee Marvin at the Internet Broadway Database

- Profile of Marvin in Film Comment

- 1924 births

- 1987 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- United States Marine Corps personnel of World War II

- American people of English descent

- American shooting survivors

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Foreign Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Male actors from New York City

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- New York (state) Democrats

- People from Woodstock, New York

- Saint Leo University alumni

- Saint Leo College Preparatory School alumni

- Silver Bear for Best Actor winners

- United States Marines