Jewels of Elizabeth II

Queen Elizabeth II owned a historic collection of jewels – some as monarch and others as a private individual. They are separate from the gems and jewels of the Royal Collection, and from the coronation and state regalia that make up the Crown Jewels.

The origin of a distinct royal jewel collection is vague, though it is believed the jewels have their origin somewhere in the 16th century. Many of the pieces are from overseas and were brought to the United Kingdom as a result of civil war, coups and revolutions, or acquired as gifts to the monarch.[1] Most of the jewellery dates from the 19th and 20th centuries.

The Crown Jewels are worn only at coronations (St Edward's Crown being used to crown the monarch) and the annual State Opening of Parliament (the Imperial State Crown). At other formal occasions, such as banquets, Elizabeth II wore the jewellery in her collection. She owned more than 300 items of jewellery,[2] including 98 brooches, 46 necklaces, 37 bracelets, 34 pairs of earrings, 20 tiaras, 15 rings, 14 watches and 5 pendants,[3] the most notable of which are detailed in this article.

History

General history

Unlike the Crown Jewels—which mainly date from the accession of Charles II—the jewels are not official regalia or insignia. Much of the collection was designed for queens regnant and queens consort, though some kings have added to the collection. Most of the jewellery was purchased from other European heads of state and members of the aristocracy, or handed down by older generations of the Royal family, often as birthday and wedding presents. In recent years, Elizabeth had worn them in her capacity as Queen of Australia, Canada and New Zealand, and can be seen wearing jewels from her collection in official portraits made specially for these realms.[4]

The House of Hanover dispute

In 1714, with the accession of George I, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Kingdom of Hanover both came to be ruled in personal union by the House of Hanover. Early Hanoverian monarchs were careful to keep the heirlooms of the two realms separate. George III gave half the British heirlooms to his bride, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, as a wedding present. In her will, Charlotte left the jewels to the 'House of Hanover'. The Kingdom of Hanover followed the Salic Law, whereby the line of succession went through male heirs. Thus, when Queen Victoria acceded to the throne of the United Kingdom, her uncle Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale became King of Hanover. King Ernest demanded a portion of the jewellery, not only as the monarch of Hanover but also as the son of Queen Charlotte. Victoria flatly declined to hand over any of the jewels, claiming they had been bought with British money. Ernest's son, George V of Hanover, continued to press the claim. Victoria's husband, Prince Albert, suggested that she make a financial settlement with the Hanoverian monarch to keep the jewels, but Parliament informed Queen Victoria they would neither purchase the jewels nor loan funds for the purpose. A parliamentary commission was set up to investigate the matter and in 1857 they found in favour of the House of Hanover. On 28 January 1858, 10 years after Ernest's death, the jewels were handed to the Hanoverian Ambassador, Count Erich von Kielmansegg.[5] Victoria did manage to keep one of her favourite pieces of jewellery: a fine rope of pearls.[6]

Ownership and value

Some pieces of jewellery made before the death of Queen Victoria in 1901 are regarded as heirlooms owned by the monarch in right of the Crown and pass from one monarch to the next in perpetuity. Objects made later, including official gifts,[7] can also be added to that part of the Royal Collection at the sole discretion of a monarch.[8] It is not possible to say how much the collection is worth because the jewels have a rich and unique history, and they are unlikely to be sold on the open market.[9]

In the early 20th century, five other lists of jewellery, which have also never been published, supplemented those left to the Crown by Queen Victoria:[10]

- Jewels left to the Crown by Her Majesty Queen Victoria

- Jewels left by Her Majesty to His Majesty the King

- Jewels left to His Majesty King Edward VII by Her Majesty Queen Victoria, hereinafter to be considered as belonging to the Crown and to be worn by all future Queens in right of it

- Jewels the property of His Majesty King George V

- Jewels given to the Crown by Her Majesty Queen Mary

- Jewels given to the Crown by His Majesty King George V

Known Heirlooms of the Crown

- The Oriental Tiara

- Queen Anne and Queen Caroline Pearl Necklaces

- Queen Adelaide’s Fringe Necklace

- The Coronation Necklace

- The Golden Jubilee Necklace

- Queen Victoria’s Bracelet

- The Coronation Earrings

- Queen Adelaide’s Brooch

- Queen Victoria’s Bow Brooches

- Queen Victoria’s Wedding Brooch (also called Prince Albert’s Brooch)

- Queen Victoria’s Wheat-Ear Brooches

- Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Brooch

- The Kent Amethysts

Tiaras

-

Queen Mary wearing the Delhi Durbar Tiara (since redesigned)

-

The Queen of New Zealand wearing the Queen Mary Fringe Tiara and the City of London Fringe Necklace

-

Elizabeth II in 1959 wearing the Vladimir tiara and the Queen Victoria Jubilee Necklace

-

The Queen of Australia wearing the Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara in an official portrait

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Burmese Ruby Tiara at a state banquet in 2019

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Kokoshnik Tiara while dancing with President Ford at the White House in 1976

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Lover's Knot Tiara at the Royal Ball, Brisbane, 1954

-

The Duchess of Cornwall wearing the Greville Tiara at a state banquet in 2019

-

The Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother) wearing the Lotus Flower Tiara in 1925

-

The Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother) wearing the Strathmore Rose Tiara in 1927

Delhi Durbar Tiara

The Delhi Durbar Tiara was made by Garrard & Co. for Queen Mary, the wife of King George V, to wear at the Delhi Durbar in 1911.[11] As the Crown Jewels never leave the country, George V had the Imperial Crown of India made to wear at the Durbar, and Queen Mary wore the tiara. It was part of a set of jewellery made for Queen Mary to use at the event which included a necklace, stomacher, brooch and earrings. Made of gold and platinum, the tiara is 8 cm (3 in) tall and has the form of a tall circlet of lyres and S-scrolls linked by festoons of diamonds. It was originally set with 10 of the Cambridge emeralds, acquired by Queen Mary in 1910 and first owned by her grandmother, the Duchess of Cambridge. In 1912, the tiara was altered to take one or both of the Cullinan III and IV diamonds; the pear-shaped diamond was held at the top, and the cushion-shaped stone hung in the oval aperture underneath.[11] Mary lent the tiara to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) for the 1947 royal tour of South Africa, and it remained with her until she died in 2002, when it passed to Elizabeth II. In 2005, Elizabeth II lent the tiara to her daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Cornwall.[11]

Queen Mary Fringe Tiara

This tiara, which can also be worn as a necklace, was made for Queen Mary in 1919. It is not, as has sometimes been claimed, made with diamonds that once belonged to George III, but reuses diamonds taken from a necklace/tiara purchased by Queen Victoria from Collingwood & Co. as a wedding present for Princess Mary in 1893. In August 1936, Mary gave the tiara to her daughter-in-law, Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother).[12] When Queen Elizabeth, consort of King George VI, first wore the tiara, Sir Henry Channon called it "an ugly spiked tiara".[13] Later, she lent the piece to her daughter, Princess Elizabeth (future Elizabeth II), as "something borrowed" for her wedding to Prince Philip in 1947.[12] As Princess Elizabeth was getting dressed at Buckingham Palace before leaving for Westminster Abbey, the tiara snapped. Luckily, the court jeweller[who?] was standing by in case of any emergency, and was rushed to his work room by a police escort. Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) reassured her daughter that it would be fixed in time, and it was.[14] The Queen Mother lent it to her granddaughter, Princess Anne, for her wedding to Captain Mark Phillips in 1973.[14] It was later lent to Princess Beatrice for her wedding to Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi in 2020.[15]

It was put on show at an exhibition with a number of other royal tiaras in 2001.[16]

Queen Adelaide’s Fringe Necklace

The Queen Adelaide’s Fringe Necklace is a circlet incorporating brilliant diamonds that were formerly owned by George III. Originally commissioned in 1830 and made by Rundell, Bridge & Co, the necklace has been worn by many queens consort.[17] Originally, it could be worn as a collar or necklace, Queen Victoria modified it so it could be mounted on a wire to form the tiara.[18] Queen Victoria wore it as a tiara during a visit to the Royal Opera in 1839. In Franz Xaver Winterhalter's painting The First of May, completed in 1851, Victoria can be seen wearing it as she holds Prince Arthur, the future Duke of Connaught and Strathearn. In a veiled reference to the adoration of the Magi, the Duke of Wellington is seen presenting the young prince with a gift.[14] It was classified as an “heirloom of the Crown” in Garrard’s 1858 inventory of Queen Victoria’s jewels.[19]

Grand Duchess Vladimir Tiara

The Grand Duchess Vladimir Tiara (ru:Владимирская тиара), sometimes the Diamond and Pearl Tiara, was bought, along with a diamond rivière, by Queen Mary from Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, mother of the Duchess of Kent, in 1921 for a price of £28,000.[20] The grand duchess, known after her marriage as Princess Nicholas of Greece, inherited it from her mother, Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna, who received it as a wedding gift from her husband in 1874. It originally had 15 large drop pearls, and was made by the jeweller Carl Edvard Bolin at a cost of 48,200 rubles.[21][22]

During the Russian Revolution in 1917, the tiara was hidden with other jewels somewhere in Vladimir Palace in Petrograd, and later saved from Soviet Russia by Albert Stopford, a British art dealer and secret agent.[23] In the years to follow, Princess Nicholas sold pieces of jewellery from her collection to support her exiled family and various charities.[24]

Queen Mary had the tiara altered to accommodate 15 of the Cambridge cabochon emeralds. The original drop pearls can easily be replaced as an alternative to the emeralds. Elizabeth II inherited the tiara directly from her grandmother in 1953.[25] It is almost exclusively worn together with the Cambridge and Delhi Durbar parures, also containing large emeralds. Elizabeth wore the tiara in her official portrait as Queen of Canada as none of the Commonwealth realms besides the United Kingdom have their own crown jewels.[24]

Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara

Elizabeth II's first tiara was a wedding present in 1947 from her grandmother, Queen Mary, who received it as a gift from the Girls of Great Britain and Ireland in 1893 on the occasion of her marriage to the Duke of York, later George V.[26] Made by E. Wolfe & Co., it was purchased from Garrard & Co. by a committee organised by Lady Eve Greville.[27] In 1914, Mary adapted the tiara to take 13 diamonds in place of the large oriental pearls surmounting the tiara. Leslie Field, author of The Queen's Jewels, described it as, "a festoon-and-scroll with nine large oriental pearls on diamond spikes and set on a base of alternate round and lozenge collets between two plain bands of diamonds". At first, Elizabeth wore the tiara without its base and pearls but the base was reattached in 1969.[28] The Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara is one of Elizabeth's most recognisable pieces of jewellery due to its widespread appearance in portraits of the monarch on British banknotes and coinage.[29]

Burmese Ruby Tiara

Elizabeth ordered the Burmese Ruby Tiara in 1973, and it was made by Garrard & Co. using stones from her private collection. It is designed in the form of a wreath of roses, with silver and diamonds making the petals, and clusters of gold and rubies forming the centre of the flowers.[30] A total of 96 rubies are mounted on the tiara; they were originally part of a necklace given to her in 1947 as a wedding present by the people of Burma (now Myanmar), who credited them with having the ability to protect their owner from sickness and evil.[31] The diamonds were also given to her as a wedding present, by the Nizam of Hyderabad and Berar, who possessed a vast jewellery collection of his own.[32]

Queen Alexandra's Kokoshnik Tiara

The Kokoshnik Tiara was presented to Alexandra, Princess of Wales, as a 25th wedding anniversary gift in 1888 by Lady Salisbury on behalf of 365 peeresses of the United Kingdom. She had always wanted a tiara in the style of a kokoshnik (Russian for "cock's comb"), a traditional Russian folk headdress, and knew the design well from a tiara belonging to her sister, Maria Feodorovna, the Empress of Russia. It was made by Garrard & Co. and has vertical white gold bars pavé-set with diamonds, the longest of which is 6.5 cm (2.5 in).[33] In a letter to her aunt, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Princess Mary wrote, "The presents are quite magnificent [...] The ladies of society gave [Alexandra] a lovely diamond spiked tiara".[34] Upon the death of Queen Alexandra, the tiara passed to her daughter-in-law, Queen Mary, who bequeathed it to Elizabeth in 1953.[35] The tiara is featured in a 1960 portrait of the Queen taken by Anthony Buckley, which was used as the banknote portrait of the Queen for several countries and territories. The tiara is also featured on a 1979 New Zealand coin effigy of the Queen designed by James Berry.

Queen Mary's Lover's Knot Tiara

In 1913, Queen Mary asked Garrard & Co. to make a copy of a tiara owned by her grandmother, Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel, using Queen Mary's own diamonds and pearls. French in its neo-classical design, the tiara has 19 oriental pearls suspended from lover's knot bows each centred with a large brilliant. Mary left the tiara to Elizabeth II, who later gave it to Diana, Princess of Wales, as a wedding present. She wore it often, notably with her 'Elvis dress' on a visit to Hong Kong in 1989, but on her divorce from Prince Charles it was returned to Elizabeth.[36] The Duchess of Cambridge has worn it to a number of state occasions since 2015.[37]

Meander Tiara

This tiara was a wedding present to Elizabeth from her mother-in-law, Princess Alice of Greece and Denmark.[38] The Meander Tiara is in the classical Greek key pattern, with a large diamond in the centre enclosed by a laurel wreath of diamonds. It also incorporates a wreath of leaves and scrolls on either side. Elizabeth II never wore this item in public, and it was given in 1972 to her daughter, Princess Anne, who has frequently worn the tiara in public, notably during her engagement to Captain Mark Phillips[39] and for an official portrait marking her 50th birthday. Anne lent the tiara to her daughter, Zara Philips, to use at her wedding to Mike Tindall in 2011.[40]

Halo Tiara

This tiara, made by Cartier in 1936, was purchased by the Duke of York (later King George VI) for his wife (later the Queen Mother) three weeks before they became king and queen. It has a rolling cascade of 16 scrolls that converge on two central scrolls topped by a diamond. Altogether, it contains 739 brilliants and 149 baton diamonds.[41] The tiara was given to Elizabeth on her 18th birthday in 1944, and was borrowed by Princess Margaret, who used it at the 1953 coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.[42] Later, Elizabeth lent the Halo Tiara to Princess Anne, before giving her the Greek Meander Tiara in 1972. The Halo Tiara was lent to the Duchess of Cambridge to wear at her wedding to Prince William in 2011.[43]

Greville Tiara

This tiara was left to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) by Dame Margaret Greville upon Greville's death in 1942. Made by Boucheron in 1920, the tiara features a honeycomb-patterned diamond lattice and was a favorite of the Queen Mother. Elizabeth II inherited the tiara from her mother in 2002 and subsequently placed it under long-term loan to the Duchess of Cornwall.[44]

Queen Mary's Diamond Bandeau Tiara

The tiara was made in 1932 for Queen Mary.[45] Its centre brooch had been a wedding gift from the County of Lincoln in 1893. The tiara is a platinum band, made up of eleven sections, a detachable centre brooch with interlaced opals and diamonds. The tiara was lent to the Duchess of Sussex to use at her wedding to Prince Harry in 2018.[46]

Lotus Flower Tiara

This tiara was created by Garrard London in the 1920s. Made out of pearls and diamonds, it was made from a necklace originally given to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) as a wedding gift. It was often worn by Princess Margaret, upon whose death, the tiara was returned to Elizabeth II. The tiara has been worn at a number of state occasions by Elizabeth II's granddaughter-in-law, the Duchess of Cambridge.[47]

Strathmore Rose Tiara

Given to the Queen Mother as a wedding gift by her father the 14th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, this floral piece was worn by the Queen Mother for a few years following her marriage. It was a part of Elizabeth II's collection since her mother's death in 2002.[47]

Greville Emerald Kokoshnik Tiara

Like the Greville [honeycomb] Tiara, this tiara was also part of Dame Margaret Greville's 1942 bequest to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother). The tiara was constructed by Boucheron in 1919 and features diamonds and several large emeralds in a kokoshnik-style platinum setting. Princess Eugenie of York wore the tiara at her October 2018 wedding; this marked the first public wearing of the tiara by a member of the royal family.[48]

Queen Mother's Cartier Bandeau

Composed of ruby, emerald, and sapphire bracelets given to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) by King George VI, the set was worn by the Queen Mother in the form of a bandeau. It is now a part of Elizabeth II's collection; she had worn the pieces individually as bracelets over the years and had also lent them to other members of the royal family.[47]

Indian Circlet, Oriental Tiara

Designed by Prince Albert and made by Garrard for Queen Victoria in 1853.[49] Originally a complete circlet set with diamonds and opals. Remodeled in 1858 to remove diamonds lost in the Hanoverian claim, leaving space open at the back of the tiara. Opals were replaced with rubies by Queen Alexandra in 1902. It is made up of 'Moghul arches and lotus flowers' in diamonds and rubies.[50][51]

Modern Sapphire Tiara

Originally belonging to Louise of Belgium, Princess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha[52] in 1858, the Queen bought this tiara in 1963 to add to her collection.[53][54]

Brazilian Aquamarine Parure Tiara

This tiara made by Garrard in 1957 comes as part of a set of necklace and earrings gifted to the Queen for her coronation in 1953 by the President Getúlio Vargas and the people of Brazil.[55] It is made up of emerald-cut aquamarines and diamonds.[56] It has been redesigned in 1971 with aquamarines given by the Governor of São Paulo in 1968.[57]

Nizam of Hyderabad Tiara

This floral diamond tiara was chosen by Princess Elizabeth and given to her on her wedding day in 1947 by Nizam of Hyderabad. It was originally made by Cartier in 1935. Dismantled in 1973, the diamonds were reused to make Burmese Ruby tiara. Rose brooches were preserved. [58][59]

Earrings

-

The Queen wearing the Coronation Earrings and matching necklace at the opening of the New Zealand Parliament in 1963. She also wore the Kokoshnik Tiara.

-

Elizabeth II wearing Greville Chandelier Earrings, 2010

Coronation Earrings

Like the Coronation Necklace, these earrings have been worn by queens regnant and consort at every coronation since 1901. Made for Queen Victoria in 1858 using the diamonds from an old Garter badge, they are of typical design: a large brilliant followed by a smaller one, with a large pear-shaped drop. The drops were originally part of the Koh-i-Noor armlet.[60] After they had been made, Victoria wore the earrings and matching necklace in the painting Queen Victoria by the European court painter, Franz Winterhalter.[61]

Queen Mary’s Floret Earrings

These earrings were made for Queen Mary by Garrards, and consist of a large central diamond surrounded by seven smaller diamonds.[62] The two large central diamonds were a wedding present from Sir William Mackinnon.[63]

Queen Mary’s Cluster Earrings

These earrings were made for Queen Mary by Garrards. The central stones were a wedding present from the Bombay Presidency.[64]

Greville Chandelier Earrings

These 7.5 cm (3 in) long chandelier earrings made by Cartier in 1929 have three large drops adorned with every modern cut of diamond.[65] The earrings were purchased by Margaret Greville, who left them to her friend the Queen Mother in 1942, and Elizabeth's parents gave them to her in 1947 as a wedding present.[66] However, she was not able to use them until she had her ears pierced. When the public noticed that her ears had been pierced, doctors and jewellers found themselves inundated with requests by women anxious to have their ears pierced too.[67]

Greville Pear-drop Earrings

As well as the chandelier earrings, and 60 other pieces of jewellery, Mrs Greville left the Queen Mother a set of pear-drop earrings that she had bought from Cartier in 1938. The pear-shaped drop diamonds each weigh about 20 carats (4 g). Diana, Princess of Wales, borrowed them in 1983 to wear on her first official visit to Australia. At a state banquet, she wore the earrings with a tiara from her family's own collection.[68] The Greville Pear-drop Earrings passed to Elizabeth II upon her mother's death in 2002.[69]

Queen Victoria's Stud Earrings

A pair of large, perfectly matched brilliant cut diamonds set as ear studs for Queen Victoria.[70]

Bahrain Diamond and Pearl Earrings

Made out of a "shell containing seven pearls" that were given to Elizabeth as a wedding gift by the Hakim of Bahrain, these earrings consist of a round diamond followed by a circle diamond from which three baguette diamonds are suspended. At the bottom, three smaller diamonds are attached to the round pearl.[71] These earrings were occasionally lent by Elizabeth II to Diana, Princess of Wales, the Countess of Wessex, and the Duchess of Cambridge.[72][73]

Necklaces

-

Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) wearing the Queen Anne and Queen Caroline pearls, 1939

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Girls of Great Britain Tiara and the Festoon Necklace

-

Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) wearing the Greville Ruby Floral Bandeau Necklace, 1950

Queen Anne and Queen Caroline Pearl Necklaces

Both necklaces consist of a single row of large graduated pearls with pearl clasps. The Queen Anne Necklace is said to have belonged to Queen Anne, the last British monarch of the Stuart dynasty. Horace Walpole, the English art historian, wrote in his diary, "Queen Anne had but few jewels and those indifferent, except one pearl necklace given to her by Prince George". Queen Caroline, on the other hand, had a great deal of valuable jewellery, including no fewer than four pearl necklaces. She wore all the pearl necklaces to her coronation in 1727, but afterwards had the 50 best pearls selected to make one large necklace. In 1947, both necklaces were given to Elizabeth by her father as a wedding present. On her wedding day, Elizabeth realised that she had left her pearls at St James's Palace. Her private secretary, Jock Colville, was asked to go and retrieve them. He commandeered the limousine of King Haakon VII of Norway, but traffic that morning had stopped, so even the king's car with its royal flag flying could not get anywhere. Colville completed his journey on foot, and when he arrived at St James's Palace, he had to explain the odd story to the guards who were protecting Elizabeth's 2,660 wedding presents. They let him in after finding his name on a guest list, and he was able to get the pearls to the princess in time for her portrait in the Music Room of Buckingham Palace.[74]

King Faisal of Saudi Arabia Necklace

A gift from King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, it is a necklace in design and set with brilliant and baguette cut diamonds. King Faisal bought the necklace, made by the American jeweller Harry Winston, and presented it to Elizabeth II while on a state visit to the United Kingdom in 1967. Before his departure, she wore it to a banquet at the Dorchester hotel. She also lent the necklace to Diana, Princess of Wales, to wear on a state visit to Australia in 1983.[75] It was loaned to the Countess of Wessex in 2012.

Festoon Necklace

In 1947, George VI commissioned a three-strand necklace with over 150 brilliant cut diamonds from his inherited collection. It consists of three small rows of diamonds with a triangle motif. The minimum weight of this necklace is estimated to be 170 carats (34 g).[67]

King Khalid of Saudi Arabia Necklace

This necklace was given to Elizabeth II by King Khalid of Saudi Arabia in 1979. It is of the sunray design and contains both round and pear shaped diamonds. Like the King Faisal necklace, it was made by Harry Winston, and Elizabeth often lent the necklace to Diana, Princess of Wales.[76]

Greville Ruby Floral Bandeau Necklace

This necklace was made in 1907 by Boucheron for Margaret Greville. It was a part of her 1942 bequest to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), and Elizabeth's parents gave them to her in 1947 as a wedding present. She wore the necklace frequently in her younger years up until the 1980s.[67] In 2017, it was loaned to the Duchess of Cambridge for a State Banquet for King Felipe VI of Spain.[77] Elizabeth II wore it again for the first time in over 30 years in 2018 at a dinner as part of the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting.[77]

Greville Festoon Necklace

Cartier had the piece designed as a 2-row necklace in 1929 but three more strands were added in 1938 at the owner's request. The piece was frequently worn by Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother throughout her life. It was worn by the Duchess of Cornwall for the first time during the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 2007.[77]

Nizam of Hyderabad Necklace

A diamond necklace made by Cartier in the 1930s. It was a wedding gift to Elizabeth on her wedding to Prince Philip from the last Nizam of Hyderabad, Mir Osman Ali Khan, in 1947. The Nizam's entire gift set for the future Queen of the United Kingdom included a diamond tiara and matching necklace, whose design was based on English roses. The tiara has three floral brooches that can be detached and used separately. The Duchess of Cambridge has also worn the necklace.[71]

Coronation Necklace

Made for Queen Victoria in 1858 by Garrard & Co., the Coronation Necklace is 38 cm (15 in) long and consists of 25 cushion diamonds and the 22-carat (4.4 g) Lahore Diamond as a pendant. It has been used together with the Coronation Earrings by queens regnant and consort at every coronation since 1901.[78]

Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee Necklace

Presented to Queen Victoria by the Duchess of Buccleuch on 30 July 1888 on behalf of the “Daughters of Her Empire”. Made by Carrington & Co. in 1888.[79]

Diamond and Pearl Choker

The four-strand piece of "layered strings of cultured pearls" was originally given to Elizabeth from Japan in the 1970s.[80][81] She wore it to many occasions, including Margaret Thatcher's 70th birthday in 1995.[81] It was loaned to Diana, Princess of Wales, for one of her first engagements as a royal, as well as a 1982 banquet at Hampton Court Palace and a trip to the Netherlands in the same year.[81][82] Later, the piece was loaned to the Duchess of Cambridge, who wore it to the 70th wedding anniversary of Elizabeth II and Prince Philip in 2017[71] as well as Philip's funeral in 2021. She later wore it for Elizabeth II's funeral in 2022.[81]

South African Necklace

In 1947, Princess Elizabeth was presented with a necklace consisting of 21 diamonds from the South African government as a 21st birthday present.[83] This was later shortened to 15 diamonds and the remainder was used to create a matching bracelet.[84]

City of London Fringe Necklace

This necklace was a gift from the City of London to Princess Elizabeth on her marriage to Philip.[85]

Delhi Durbar Necklace

This necklace was made by Garrards in 1911 for Queen Mary as part of a suite of jewellery made for the 1911 Delhi Durbar.[86] The diamond pendant is the Cullinan VII, and the 9 cabochon emeralds are from a cache of 40 emeralds won by Princess Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge in a State lottery in Frankfurt.[87]

Bracelets

Queen Victoria’s Bracelet

This large bracelet is made of five square foliage pieces. It was worn by Queen Victoria for her official Golden Jubilee portrait photograph.[88] It was classified as an ‘heirloom of the Crown’ in 1858.

Queen Mary’s Bangles

This pair of bangles were a wedding present from the Bombay Presidency. They were given to Princess Elizabeth by Queen Mary as a wedding present.[89]

Rings

Cullinan IX Ring

This ring was thought to be made by Garrards in 1911, and is made using the smallest of the main stones cut from the Cullinan diamond (4.4 carat pear-shaped diamond.[90]

Brooches

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Prince Albert Sapphire Brooch, 2012

-

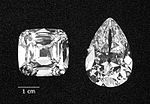

Cullinan diamonds IV and III

-

Cullinan V brooch

-

The Duchess of Cambridge wearing the Maple leaf brooch, 2011

-

The Queen wearing the New Zealand Silver Fern Brooch during the Royal tour of New Zealand, 1953

-

Australian Wattle Spray Brooch

Queen Adelaide’s Brooch

The brooch was made by Rundell, Bridge & Co. in 1831. It was originally commissioned by William IV for Queen Adelaide as a clasp to a necklace.[91] Subsequent Queens have always worn it as a brooch. It is classified as an “heirloom of the Crown” and was inherited by Queen Elizabeth II in 1952.[92]

Prince Albert Sapphire Brooch

The Prince Albert sapphire brooch was given by Prince Albert to Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace on 9 February 1840. It was the day before their wedding, and Victoria wrote in her diary that Albert came to her sitting room and gave her "a beautiful sapphire and diamond brooch".[93]

Queen Victoria's Diamond Fringe Brooch

This piece is made out of "nine chains pave-set with brilliant-cut diamonds" at the bottom and larger diamonds put together at the top, which were given to Queen Victoria by the Ottoman Sultan in 1856. The piece was frequently worn by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, and after her death it formed part of Elizabeth II's collection.[94]

Queen Victoria’s Bow Brooches

These brooches were made in 1858 for Queen Victoria by R. & S. Garrard & Co.[95] They were designated as “heirlooms of the Crown” by Queen Victoria.[96]

Queen Victoria’s Wheat-Ear Brooches

Six wheat-ear brooches or hair ornaments were commissioned by William IV for Queen Adelaide, and made in 1830 by Rundell, Bridge & Co.[97] Three were remade in 1858 after the successful Hanover claim. They were designated heirlooms of the crown by Queen Victoria.[98]

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Brooch

Made by Garrard in 1897, and was given to her by her Household as part of her Diamond Jubilee celebrations. It was designated as an “heirloom of the Crown” by Queen Victoria.[99]

Queen Mary's Dorset Bow Brooch

Made out of gold and silver and set with pave-set brilliants and a hinged pendant loop, the brooch resembles a ribbon-tied bow.[100] The piece was made in 1893 by Carrington & Co. as a wedding present by County of Dorset to Mary, Duchess of York (later Queen Mary).[100] Mary gave the brooch to her granddaughter Princess Elizabeth (later Elizabeth II) in 1947 as a wedding present.

Duchess of Cambridge's Pearl Pendant Brooch

Made by Garrard for Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge, it features a large pearl surrounded by a cluster of diamonds.[101] Hanging from it as a pendant is a smaller pearl.[101] It was inherited by Augusta's daughter, Mary Adelaide, Duchess of Teck, who passed it on to her daughter, Queen Mary.[101] The piece had been worn occasionally by Queen Elizabeth II and appeared in the first formal joint portrait of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, with her husband Prince William.[101]

Richmond Brooch

The Richmond Brooch was made by Hunt and Raskell in 1893, and given to Queen Mary as a wedding present.[102] She wore it on her honeymoon, and bequeathed it to Elizabeth after her death.[102] It features "diamonds, set with two pearls—one large round center pearl and the detachable pearl", as well as a pear-shaped, pearl-drop component that is removable.[102] The grand diamond piece is one of the largest within Elizabeth II's collection.[102] Elizabeth had worn it to many evening receptions and engagements, including the 2018 Festival of Remembrance and the 2021 funeral of her husband.[103]

Cullinan III & IV ("Granny's Chips")

Cullinan III and IV are two of several stones cut from the Cullinan Diamond in 1905. The large diamond, found in South Africa, was presented to Edward VII on his 66th birthday. Two of the stones cut from the diamond were the 94.4-carat (18.88 g) Cullinan III, a clear pear-shaped stone, and a 63.6-carat (12.72 g) cushion-shaped stone. Queen Mary had these stones made into a brooch with the Cullinan III hanging from IV. Elizabeth II inherited the brooch in 1953 from her grandmother. On 25 March 1958, while she and Prince Philip were on a state visit to the Netherlands, she revealed that Cullinan III and IV are known in her family as "Granny's Chips". The couple visited the Asscher Diamond Company, where the Cullinan had been cut 50 years earlier. It was the first time the Queen had publicly worn the brooch. During her visit, she unpinned the brooch and offered it for examination to Louis Asscher, the brother of Joseph Asscher who had originally cut the diamond. Elderly and almost blind, Asscher was deeply moved by her bringing the diamonds, knowing how much it would mean to him seeing them again after so many years.[104]

Cullinan V

The smaller 18.8-carat (3.76 g) Cullinan V is a heart-shaped diamond cut from the same rough gem as III and IV. It is set in the centre of a platinum brooch that formed a part of the stomacher made for Queen Mary to wear at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. The brooch was designed to show off Cullinan V and is pavé-set with a border of smaller diamonds. It can be suspended from the VIII brooch and can be used to suspend the VII pendant. It was often worn like this by Mary who left all the brooches to Elizabeth when she died in 1953.[105]

Cullinan VI and VIII Brooch

The Cullinan VI stone (11.5 carats) was bought for Queen Alexandra by Edward VII in 1908.[106] Since Queen Mary inherited it, it has been worn as a pendant to the Cullinan VIII brooch (6.8 carats). [107]

Diamond Maple Leaf Brooch

The piece was crafted by J. W. Histed Diamonds Ltd. in Vancouver, Canada.[108] It holds baguette-cut diamonds mounted in platinum, formed in the shape of the sugar maple tree leaf, the national emblem of Canada.[108][109] The brooch was originally presented to Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother) on her tour of Canada with her husband in 1939.[109] The piece was worn by Elizabeth II, then a princess, on her 1951 trip to Canada, and multiple instances since both within the country and in Britain.[109][108] It was worn by the Duchess of Cornwall on her trips to the nation in 2009 and 2012.[109][108] The Duchess of Cambridge has worn it during both her tours of Canada in 2011 and 2016.[108]

The Queen’s Cartier Aquamarine Clips

This pair of aquamarine and diamond clips was given to Princess Elizabeth as an 18th birthday present by her parents.[110]

New Zealand Silver Fern Brooch

The brooch was given to Elizabeth II by Annie Allum, wife of John Allum, Mayor of Auckland, during her 1953 visit to New Zealand,[111][71] as a Christmas present "from the woman of Auckland".[111] It is "bejewelled with round brilliant and baguette shaped diamonds", having been designed to form the shape of a fern, an emblem of New Zealand.[111][112] Various members of the royal family have worn the piece on visits to the country, including the Duchess of Cambridge.[111][71]

Australian Wattle Spray Brooch

The Queen owns a Wattle brooch, which was gifted to her by Prime Minister Robert Menzies on behalf of the Government and people of Australia on her first visit in 1954.[113][114] Made of platinum, and set with yellow and white diamonds, the brooch is in the form of a spray of wattle, and tea tree blossoms.[113][115] The Queen had worn the brooch many times on her visits to Australia, for instance, at the Randwick Racecourse in Sydney in 1970, Sydney Opera House in 2000, and during her arrival to Canberra in 2006 and 2011, or to Australia-related events in Britain.[113][116]

Sapphire Jubilee Snowflake Brooch

The Governor-General of Canada, David Johnston, presented Elizabeth II with the Sapphire Jubilee Snowflake Brooch at a celebration of Canada's sesquicentennial at Canada House on 19 July 2017 as a gift from the Government of Canada to celebrate her Sapphire Jubilee and to commemorate Canada 150.[117][118] David Johnston presented her with the brooch moments before she and the Duke of Edinburgh unveiled a new Jubilee Walkway panel outside Canada House. The brooch was designed as a companion to the diamond maple leaf brooch, the piece was made by Hillberg and Berk of Saskatchewan and consists of sapphires from a cache found in 2002 on Baffin Island by brothers Seemeega and Nowdluk Aqpik.[citation needed]

Infinity Isle of Man Brooch

To mark her Platinum Jubilee, the Manx government gave the Queen a brooch in the shape of island, made there by Element Isle. The 'Infinity Isle of Man' brooch design outlines the Island with four gems (Blue Topaz, Citrine, Amethyst and Emerald) representing the towns of Ramsey, Peel, Castletown and the city of Douglas. The colours of the stones were selected to represent Manx tartan.[119]

Greville Scroll Brooch

Made by Cartier in 1929, the piece features "three pearls anchoring a simple diamond-flecked scroll design" and was worn by the Queen Mother who eventually passed it down to the Queen.[77]

Sri Lankan Trumpet Brooch

Gifted by the mayor of Colombo to the Queen during her state visit in 1981, the piece features "pink, blue and yellow sapphires, garnets, rubies and aquamarine."[120][121]

Parures

A parure is a set of matching jewellery to be used together which first became popular in 17th-century Europe.

-

Elizabeth II wearing the Aquamarine Tiara with the Brazil necklace, earrings and bracelet

-

Elizabeth II wearing the George VI Victorian Suite

The Kent Demi-Parure

This set of jewellery was owned by Queen Victoria’s mother, the Duchess of Kent. The set consists of a necklace, three brooches, a pair of earrings, and a pair of haircombs.[122]

Brazil Parure

The Brazil Parure is one of the newest items of jewellery in the collection. In 1953, the president and people of Brazil presented Elizabeth II with the coronation gift of a necklace and matching pendant earrings of aquamarines and diamonds.[123] It had taken the jewellers Mappin & Webb an entire year to collect the perfectly matched stones. The necklace has nine large oblong aquamarines with an even bigger aquamarine pendant drop. Elizabeth II had the drop set in a more decorative diamond cluster and it is now detachable. She was so delighted with the gift that in 1957 she had a tiara made to match the necklace.[123] The tiara is surmounted by three vertically set aquamarines. Seeing that she had so liked the original Coronation gift that she had a matching tiara made, the Government of Brazil decided to add to its gift, and in 1958 it presented her with a bracelet of oblong aquamarines set in a cluster of diamonds, and a square aquamarine and diamond brooch.[124]

George VI Victorian Suite

The George VI Victorian Suite was originally a wedding present by George VI to his daughter Elizabeth in 1947. The suite consists of a long necklace of oblong sapphires and diamonds and a pair of matching square sapphire earrings also bordered with diamonds. The suite was originally made in 1850. The stones exactly matched the colour of the robes of the Order of the Garter. Elizabeth had the necklace shortened by removing the biggest sapphire in 1952, and later had a new pendant made using the removed stone. In 1963, a new sapphire and diamond tiara and bracelet were made to match the original pieces. The tiara is made out of a necklace that had belonged to Princess Louise of Belgium, daughter of Leopold II. In 1969, Elizabeth wore the complete parure to a charity concert.[125]

Queen Alexandra Wedding Parure

This set, a larger diamond and pearl parure made by Garrard in 1862, was commissioned by Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) for his bride Alexandra of Denmark.[126] It included an all-diamond tiara with knot and fleur-de-lis motifs, accompanied by a necklace, a brooch, and a pair of earrings, which feature button-style pearl and diamond clusters and pear-shaped pearl pendants.[126] On Alexandra's death, the tiara, known as the "Rundell Tiara", passed to her daughter Princess Victoria, and was disposed of by her.[127] The rest of the parure was passed down to Queen Mary, who wore the brooch and lent the necklace to her daughter-in-law, the Duchess of York (later Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother).[126] The necklace became a favourite of hers, and upon her death it was bequeathed to Elizabeth II, who lent it to her granddaughter-in-law, the Duchess of Cambridge.[126]

Greville Emerald Suite

The exact origin of the suite, which consists of an emerald necklace and emerald earrings, is unknown.[77] The necklace features square-cut emeralds set in diamond clusters, and the earrings consist of pear-shaped cabochon emeralds suspended from diamond studs. The suite was frequently worn by the Queen Mother and later passed on to the Queen.[77]

Dubai Sapphire Suite

In 1979, the ruler of Dubai, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, gifted the Queen a suite from Asprey, which included a necklace of diamond loops, a pair of earrings and a ring, during the Queen's tour of the Gulf States. The earrings were worn by the Duchess of Cambridge at a movie screening in 2021.[126]

Emerald Tassel Suite

First worn by the Queen in the 1980s, the suite consists of a necklace, a pair of earrings, a bracelet, and a ring. The earrings and the bracelet were worn by the Duchess of Cambridge during a tour of Jamaica in 2022.[126]

1937 coronets

For the coronation of their parents in 1937, it was decided that Elizabeth and Margaret should be given small versions of crowns to wear at the ceremony. Ornate coronets of gold lined with crimson and edged with ermine were designed by Garrard & Co. and brought to the royal couple for inspection. However, the king and queen decided they were inappropriately elaborate and too heavy for the young princesses.[128] Queen Mary suggested the coronets be silver-gilt in a medieval style with no decorations. George VI agreed, and the coronets were designed with Maltese crosses and fleurs-de-lis. After the coronation, Mary wrote: "I sat between Maud and Lilibet (Elizabeth), and Margaret came next. They looked too sweet in their lace dresses and robes, especially when they put on their coronets".[129] The coronation ensembles are in the Royal Collection Trust.[130]

See also

- Canadian royal clothing and jewellery

- Crown Jewels of the United Kingdom

- Jewels of Diana, Princess of Wales

- George IV State Diadem

- Royal Family Order

- Jewels of Mary, Queen of Scots

- Jewels of Anne of Denmark

References

- ^ Suzy Menkes (1990). The Royal Jewels. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4315-6.[page needed]

- ^ Bonnie Johnson (25 January 1988). "Yank Leslie Field traces the rich history of the Queen's jewels". People. 29 (3). Retrieved 28 December 2015.

- ^ Keith Dovkants (28 January 2014). "The Monarch and her money". Tatler. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Field, p. 9.

- ^ Field, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Helen Rappaport (2003). Queen Victoria: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-85109-355-7.

- ^ "Force the Royal Family to declare gifts, say MPs". Evening Standard. London. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ^ Andrew Morton (1989). Theirs Is the Kingdom: The Wealth of the Windsors. Michael O'Mara Books. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-948397-23-3.

- ^ Hannah Betts (30 June 2012). "'Diamonds' for a Diamond Queen". The Telegraph. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Edward Francis Twining (1960). A History of the Crown Jewels of Europe. B. T. Batsford. p. 189. ASIN B00283LZA6.

- ^ a b c "Delhi Durbar Tiara". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b "Fringe Tiara". Royal Collection Trust.

- ^ Penelope Mortimer (1986). Queen Elizabeth: Life of the Queen Mother. Viking. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-670-81065-9.

- ^ a b c Field, pp. 41–43.

- ^ Woodyatt, Amy; Picheta, Rob; Foster, Max (18 July 2020). "Princess Beatrice, daughter of Prince Andrew, releases photos of her private wedding". CNN. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ "Queen and Sir Elton put tiaras on show". The Telegraph. London. 24 December 2001. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. p. 28. ISBN 978 1 905686 38 4.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. p. 28. ISBN 978 1 905686 38 4.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. p. 28. ISBN 978 1 905686 38 4.

- ^ "2:2". De Kongelige Juveler (in Danish). 2011. DR.

- ^ Г.Н. Корнева, Т. Н. Чебоксарова. Великая княгиня Мария Павловна. Лики России. 2014 г. С-Петербург.

- ^ Osipova, I. (27 January 2018). "5 mysterious stories involving Russia's royal jewelry". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Magnificent Jewels" (PDF). Sotheby's. 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b Field, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Stanley Jackson (1975). Inside Monte Carlo. W. H. Allen. p. 127. ISBN 0-4910-1635-2.

- ^ Field, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Caroline Davies (2 May 2007). "Portrait of royalty reaches across the decades". The Telegraph. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ "A Royal Wedding: The Girls of Great Britain tiara". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "Queen Mary's Girls of Great Britain and Ireland Tiara". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016.

- ^ Field, p. 69.

- ^ The Gemmologist. Vol. 16. Gemmological Association of Great Britain. 1947. p. 368.

- ^ Usha R. Balakrishnan (2001). Jewels of the Nizams. India: Department of Culture. p. 60. ISBN 978-81-85832-15-9.

- ^ "Queen Alexandra's Kokoshnik Tiara". Royal Collection Trust. 29 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- ^ Ladies' Home Journal. Vol. 76. LHJ Publishing. 1959. p. 105.

- ^ Vol, Stellene; es (13 August 2019). "The Romanovs' Favorite Style of Tiara Is Back on Trend (Seriously)". Town & Country. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Field, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Lucy Clarke-Billings (9 December 2015). "Duchess of Cambridge wears Princess Diana's favourite tiara to diplomatic reception at Buckingham Palace". The Telegraph. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Anne Edwards (1990). Royal Sisters: Queen Elizabeth II and Princess Margaret. Morrow. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-688-07662-7.

- ^ Field, p. 47.

- ^ "British royal wedding tiaras: See the jewels worn by princess brides". Hello!. 19 May 2018. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ "The Halo Tiara". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- ^ Geoffrey C. Munn (2001). Tiaras: A History of Splendour. Antique Collectors' Club. p. 173. ISBN 978-1-85149-375-3.

- ^ "Royal wedding: Kate Middleton wears Queen's tiara". The Telegraph. 29 April 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ "Best Royal Family Jewelry of All Time". 10 October 2018.

- ^ Engel Bromwich, Jonah (19 May 2018). "Meghan Markle's Tiara: It's Sparkly". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ "Meghan Markle's Wedding Tiara: Everything You Need to Know". Brides. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ a b c Bruner, Raisa (3 May 2018). "Analyzing Every Tiara Meghan Markle Could Wear at the Royal Wedding". Time. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "Princess Eugenie's Wedding Tiara Was Her Something Borrowed". 12 October 2018.

- ^ "The Oriental Tiara". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ "40 Exquisite Tiaras Owned By The British Royal Family". Marie Claire. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Originally a complete circlet set with diamonds and opals. Remodeled in 1858 to remove diamonds lost in the Hanoverian claim, leaving space open at the back of the tiara.

- ^ "The Belgian Sapphire Tiara". The Court Jeweller. 1 September 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Sapphire and diamond Tiara, Sapphire Parure of necklace and earrings |Queen Elizabeth II Royal Jewels". royal-magazin.de. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "40 Exquisite Tiaras Owned By The British Royal Family". Marie Claire. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth II. Aquamarines Parure, Diadem, Earpendants, Brooch and Bracelet| Queens Jewels". royal-magazin.de. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "40 Exquisite Tiaras Owned By The British Royal Family". Marie Claire. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ https://royal-magazin.de/england/queen/aquamarine-parure-queen.htm

- ^ "40 Exquisite Tiaras Owned By The British Royal Family". Marie Claire. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ https://www.thecourtjeweller.com/2017/11/the-nizam-of-hyderabad-suite.html

- ^ "The Coronation Earrings". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Queen Victoria". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 405131.

- ^ Field, Leslie (1987). The Queen’s Jewels. Abradale Press. p. 44.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. p. 213.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. p. 212.

- ^ "The Greville Chandelier Earrings". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Don Coolican (1986). Tribute to Her Majesty. Windward/Scott. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7112-0437-9.

- ^ a b c Field, p. 53.

- ^ Field, p. 52.

- ^ "The Greville Pear-drop Earrings". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Field, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c d e Angelica Xidias (12 June 2019). "The crown jewels: every piece of jewellery Kate Middleton has borrowed or been gifted by the royal family". Vogue Australia. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "All the times Kate borrowed pieces from the Queen's jewelry box". Hello!. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Petit, Stephanie (28 August 2018). "Kate Middleton Dipped Into the Queen's Jewelry Box for Their Church Outing: See the Photo!". People. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ Field, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Field, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Field, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Kim, Leena (12 December 2021). "Who Was Margaret Greville—the Socialite Who Left Her Jewels to the Royal Family?". Town & Country. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ "The Coronation Necklace". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. pp. 68–73.

- ^ Hess, Liam (17 April 2021). "The Deeper Meaning Behind Kate Middleton's Pearl Necklace". Vogue. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Hosken, Olivia (19 April 2021). "What the Pearl Necklace Kate Middleton Wore to Prince Philip's Funeral Signifies". Town & Country. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Gonzales, Erica (17 April 2021). "Kate Middleton Wore the Queen's Pearl Necklace to Prince Philip's Funeral". Harper's Bazaar. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "The South African Necklace". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "The South African Bracelet". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "The Queen's City of London Necklace". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ "Delhi Durbar Necklace and Cullinan VII Pendant". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Field, p. 88.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Publications. pp. 44–45.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. p. 153. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ "Cullinan IX Ring". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. pp. 34–37. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. p. 34. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ Evert A. Duyckinck (1873). Portrait Gallery of Eminent Men and Women of Europe and America. Vol. 2. Johnson, Wilson. p. 101.

- ^ "Queen Victoria's Diamond Fringe Brooch". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. pp. 60–61. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. pp. 60–61. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. pp. 64–67.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. pp. 64–67.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh (2012). The Queen’s Diamonds. Royal Collection Trust. pp. 74–77. ISBN 1905686382.

- ^ a b "Queen Mary's Dorset bow brooch 1893". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d Whitehead, Joanna (23 June 2022). "Kate Middleton wears Queen's Duchess of Cambridge brooch for first time in new portrait". The Independent. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d Weaver, Hilary (19 April 2021). "Queen Elizabeth Wore a Deeply Symbolic Brooch to Prince Philip's Funeral". Town & Country. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "The Richmond Brooch". Royal Exhibitions. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Kenneth J. Mears (1988). The Tower of London: 900 Years of English History. Phaidon. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-7148-2527-4.

- ^ "The diamonds and their history" (PDF). Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "Cullinan VI and VIII Brooch". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ "Cullinan VI and VIII Brooch". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "The Story Behind Kate Middleton's Maple Leaf Brooch". Harper's Bazaar. 28 September 2016. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Strong, Gemma (July 2020). "The Queen's jewellery: A closer look at one of her most treasured gems". Hello!. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Field, Leslie (1987). The Queen’s Jewels. Abradale Press. p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Malivindi, Diandra. "A Brief History Of Queen Elizabeth II's Ornate And Jaw-Dropping Brooch Collection". Marie Claire. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ Gruffyd, Mared (23 February 2021). "Queen's silver fern brooch 'perfect symbol' of Her Majesty's 'personal qualities'". Express. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Queen wears special Australian jewel for meeting with Prime Minister Scott Morrison". 9Honey. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "The Queen's Australian Wattle brooch". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "A guide to The Queen's collection of brooches, which are more influential than you think". Vogue Australia. 20 July 2021.

- ^ "The Austraian Wattle Brooch". The Court Jeweller. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ General, The Office of the Secretary to the Governor. "The Governor General of Canada". Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Canada Plus – August 2017". Global Affairs Canada, UK Embassy. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Platinum Jubilee: Isle of Man brooch marks Queen's reign". BBC News. 1 June 2022.

- ^ "Sri Lankan Brooch 1981". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ "SLGJA recalls late Queen Elizabeth II and her love for Sri Lankan gemstones".

- ^ Field, Leslie (1987). The Queen’s Jewels. Abradale Press. p. 22.

- ^ a b "Dress for the Occasion". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Field, p. 21.

- ^ Field, pp. 148–149.

- ^ a b c d e f Crawford-Smith, James (9 April 2022). "Eight Times Kate Middleton Borrowed Queen Elizabeth II's Diamonds". Newsweek. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Hugh, The Queen's Diamonds (2012), Royal Collection Trust

- ^ Field, p. 179.

- ^ Helen Cathcart (1974). Princess Margaret. W. H. Allen. p. 36. ISBN 0-4910-1621-2.

- ^ "Ensembles worn by Princess Elizabeth and Princess Margaret for the Coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth". Royal Collection Trust. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Field, Leslie (2002). The Queen's Jewels: The Personal Collection of Elizabeth II. London: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-8172-6.