Lod

Template:Infobox Israel municipality Lod (Template:Lang-he-n, Template:Hebrew; Arabic: اللد al-Lidd, al-Ludd; Latin: Lydda, Diospolis, Ancient Greek: Λύδδα / Διόσπολις – city of Zeus) is a city 15 km (9.3 mi) southeast of Tel Aviv in the Central District of Israel. In 2022 it had a population of 85,351.[1]

The name is derived from the Biblical city of Lod,[2][3] and it was a significant Judean town from the Maccabean Period to the early Christian period. During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War most of the city's Arab inhabitants were expelled in the 1948 Palestinian exodus from Lydda and Ramle.[4][5] The town was resettled by Jewish immigrants, most of them from Arab countries,[6][7] alongside 1,056 Arabs who remained.[6] Today, the city has an Arab population of 30%.[8]

Israel's main international airport, Ben Gurion Airport (previously known as Lydda Airport, RAF Lydda, and Lod Airport) is located on the outskirts of the city.

Biblical references

The Hebrew name Lod appears in the Hebrew Bible as a town of Benjamin, founded along with Ono by Shamed or Shamer (1 Chronicles 8:12; Ezra 2:33; Nehemiah 7:37; 11:35). In Ezra 2:33, it is mentioned as one of the cities whose inhabitants returned after the Babylonian captivity. Lod is not mentioned among the towns allocated to the tribe of Benjamin in Joshua 18:11–28.[9]

In the New Testament, the town appears in its Greek form, Lydda,[10][11][12] as the site of Peter's healing of a paralytic man in Acts 9:32-38.[13]

Islamic reference

The city also finds reference in an Islamic Hadith, as the location of the battlefield where the antichrist (Dajjal) will be slain before the Day of Judgment.[14]

History

Prehistory

Pottery finds have dated the initial settlement in the area now occupied by the town to 5600–5250 BCE.[15]

Bronze Age

The earliest written record is in a list of Canaanite towns drawn up by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III at Karnak in 1465 BCE.[16]

Kingdom of Judah till First Jewish–Roman War

From the fifth century BCE until the Roman conquest in 70 CE, the city was a centre of Jewish scholarship[17] and commerce.[18] According to Martin Gilbert, during the Hasmonean period, Jonathan Maccabee and his brother Simon Maccabaeus enlarged the area under Jewish control, which included conquering the city.[19]

Roman period

In 43 BC, Cassius, the Roman governor of Syria, sold the inhabitants of Lod into slavery, but they were set free two years later by Mark Antony.[20][21] During the First Jewish–Roman War, the Roman proconsul of Syria, Cestius Gallus, razed the town on his way to Jerusalem in 66 CE. It was occupied by Emperor Vespasian in 68 CE.[22]

In the period following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Rabbi Tarfon, who appears in many Tannaitic and Jewish legal discussions, served as a rabbinic authority in Lod.[23]

During the Kitos War, 115–117 CE, the Roman army laid siege to Lod, where the rebel Jews had gathered under the leadership of Julian and Pappos. Torah study was outlawed by the Romans and pursued mostly in the underground.[24] The distress became so great, the patriarch Rabban Gamaliel II, who was shut up there and died soon afterwards, permitted fasting on Ḥanukkah. Other rabbis disagreed with this ruling.[25] Lydda was next taken and many of the Jews were executed; the "slain of Lydda" are often mentioned in words of reverential praise in the Talmud.[26]

In 200 CE, emperor Septimius Severus elevated the town to the status of a city, calling it Colonia Lucia Septimia Severa Diospolis.[27] The name Diospolis ("City of Zeus") may have been bestowed earlier, possibly by Hadrian.[28] At that point, most of its inhabitants were Christian. The earliest known bishop is Aëtius, a friend of Arius.[20]

Byzantine period

This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (June 2016) |

In December 415, the Council of Diospolis was held here to try Pelagius; he was acquitted. In the sixth century, the city was renamed Georgiopolis[29] after St. George, a soldier in the guard of the emperor Diocletian, who was born there between 256 and 285 CE.[30] The Church of St George is named for him.[16] The 6th-century Madaba map shows Lydda as an unwalled city with a cluster of buildings under a black inscription reading "Lod, also Lydea, also Diospolis". An isolated large building with a semicircular colonnaded plaza in front of it might represent the St George shrine.[31]

Early Muslim period

After the Muslim conquest of Palestine by Amr ibn al-'As in 636 CE,[32] Lod which was referred to as "al-Ludd" in Arabic served as the capital of Jund Filastin ("Military District of Palaestina") before the seat of power was moved to nearby Ramla during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph Suleiman ibn Abd al-Malik in 715–716. The population of al-Ludd was relocated to Ramla, as well.[33] With the relocation of its inhabitants and the construction of the White Mosque in Ramla, al-Ludd lost its importance and fell into decay.[34]

The city was visited by the local Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi in 985, when it was under the Fatimid Caliphate, and was noted for its Great Mosque which served the residents of al-Ludd, Ramla, and the nearby villages. He also wrote of the city's "wonderful church (of St. George) at the gate of which Christ will slay the Antichrist."[35]

Crusader and Ayyubid period

The Crusaders occupied the city in 1099 and named it St. Jorge de Lidde.[18] It was briefly conquered by Saladin, but retaken by the Crusaders in 1191. The Crusaders built a cathedral, currently changed to become the Great Mosque of Ramla—one of Israel's best-preserved Crusader churches.[36] For the English Crusaders, it was a place of great significance as the birthplace of Saint George. The Crusaders made it the seat of a Latin rite diocese,[37] and it remains a titular see.[20] It owed the service of 10 knights and 20 sergeants, and it had its own burgess court during this era.[38]

In 1226, Ayyubid Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi visited al-Ludd and stated it was part of the Jerusalem District during Ayyubid rule.[39]

Mamluk period

Sultan Baybars brought Lydda again under Muslim control by 1267–8.[40] According to Qalqashandi, Lydda was an administrative centre of a wilaya during the fourteenth and fifteenth century in the Mamluk empire.[40] Mujir al-Din described it as a pleasant village with an active Friday mosque.[40][41] During this time, Lydda was a station on the postal route between Cairo and Damascus.[40][42]

Ottoman period

In 1517, Lydda was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire as part of the Damascus Eyalet, and in the 1550s, the revenues of Lydda were designated for the new waqf of Hasseki Sultan Imaret in Jerusalem, established by Hasseki Hurrem Sultan (Roxelana), the wife of Suleiman the Magnificent.[43]

By 1596 Lydda was a part of the nahiya ("subdistrict") of Ramla, which was under the administration of the liwa ("district") of Gaza. It had a population of 241 households and 14 bachelors who were all Muslims, and 233 households who were Christians.[44] They paid a fixed tax-rate of 33,3 % on agricultural products, including wheat, barley, summer crops, vineyards, fruit trees, sesame, special product ("dawalib" =spinning wheels[40]), goats and beehives, in addition to occasional revenues and market toll, a total of 45,000 Akçe. All of the revenue went to the Waqf.[45]

The village appeared as Lydda, though misplaced, on the map of Pierre Jacotin compiled in 1799.[46]

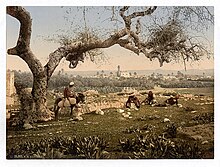

The missionary Dr. William M. Thomson visited Lydda in the mid-19th century, describing it as a "flourishing village of some 2,000 inhabitants, imbosomed in noble orchards of olive, fig, pomegranate, mulberry, sycamore, and other trees, surrounded every way by a very fertile neighbourhood. The inhabitants are evidently industrious and thriving, and the whole country between this and Ramleh is fast being filled up with their flourishing orchards. Rarely have I beheld a rural scene more delightful than this presented in early harvest ... It must be seen, heard, and enjoyed to be appreciated."[47]

In 1869, the population of Ludd was given as: 55 Catholics, 1,940 "Greeks", 5 Protestants and 4,850 Muslims.[48] In 1870, the Church of Saint George was rebuilt. In 1892, the first railway station in the entire region was established in the city.[49] In the second half of the 19th century, Jewish merchants migrated to the city, but left after the 1921 Jaffa riots.[49]

In 1882, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described Lod as "A small town, standing among enclosure of prickly pear, and having fine olive groves around it, especially to the south. The minaret of the mosque is a very conspicuous object over the whole of the plain. The inhabitants are principally Moslim, though the place is the seat of a Greek bishop resident of Jerusalem. The Crusading church has lately been restored, and is used by the Greeks. Wells are found in the gardens...."[48]

British Mandate

From 1918, Lydda was under the administration of the British Mandate in Palestine, as per a League of Nations decree that followed the Great War. During the Second World War, the British set up supply posts in and around Lydda and its railway station, also building an airport that was renamed Ben Gurion Airport after the establishment of Israel.[49]

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, Lydda had a population of 8,103 inhabitants; 7,166 Muslims, 11 Jews and 926 Christians,[50] the Christians were 921 Orthodox, 4 Roman Catholics and 1 Melkite.[51] This had increased by the 1931 census to 11,250; 10,002 Muslims, 28 Jews, 1,210 Christians and 10 Bahai, in a total of 2475 residential houses.[52]

In 1945 Lydda had a population of 16,780; 14,910 Muslims, 1,840 Christians, 20 Jews and 10 classified as "other".[53] Until 1948, Lydda was an Arab town with a population of around 20,000—18,500 Muslims and 1,500 Christians.[54][55] In 1947, the United Nations proposed dividing Mandatory Palestine into two states, one Jewish state and one Arab; Lydda was to form part of the proposed Arab state.[56] In the ensuing war, Israel captured Arab towns outside the area the UN had allotted it, including Lydda.

State of Israel

1948 War

The Israel Defense Forces entered Lydda on 11 July 1948.[57] The following day, under the impression that it was under attack,[58] the 3rd Battalion was ordered to shoot anyone "seen on the streets". According to Israel, 250 Arabs were killed. Other estimates are higher: Arab historian Aref al Aref estimated 400, and Nimr al Khatib 1,700.[59][60]

During 1948, the population rose to 50,000 people as Arab refugees fleeing other areas made their way there.[49] All but 700[61] to 1,056[6] were expelled by order of the Israeli high command, and forced to walk 17 km (11 mi) to the Jordanian Arab Legion lines. Estimates of those who died from exhaustion and dehydration vary from a handful to 355.[62][63] The town was subsequently sacked by the Israeli army.[64] A disputed claim, advanced by scholars including Ilan Pappé, characterizes this as ethnic cleansing.[65] The few hundred Arabs who remained in the city were not permitted to live in their own homes.[66] They were soon outnumbered by the influx of Jewish refugees who moved into the town from August 1948 onwards, most of them from Arab countries.[6] as a result of which Lydda became a predominantly Jewish town.[55][67]

-

Lydda five months after Operation Danny. December 1948.

-

Lydda, 1948

-

St George's Church, Lydda, after the battle. 1948

-

Palmach 3 inch mortar in front of Lydda mosque. 1948

Resettlement of Lod

The Jewish immigrants who settled Lod came in waves, first from Morocco and Tunisia, later from Ethiopia, and then from the former Soviet Union.[68] As a result, the city's logo (coat of arms) is inscribed with Biblical words from Jeremiah 31:17Template:Bibleverse with invalid book: "The children will return to their country."[citation needed]

2000s

Although the city has been plagued by a poor image for decades, as of 2008 dozens of projects were under way to improve life in the city. New upscale neighbourhoods are expanding the city to the east, among them Ganei Ya'ar and Ahisemah.[69] According to the Economist, a three-meter-high wall was erected in 2010 to separate Jewish and Arab neighbourhoods, and limits have been imposed on Arab building, whereas construction in the Jewish areas is promoted. Some municipal services, such as street lighting and rubbish collection, are only provided to Jewish areas. Violent crime in the Arab neighbourhoods of Lod is largely directed at other Arabs and revolves around family feuds over turf and honour crimes.[70] In 2010, the Lod Community Foundation organised an event for representatives of bicultural youth movements, volunteer aid organisations, educational start-ups, businessmen, sports organizations, and conservationists who are working on programmes to better the city.[71]

The city continues to influence the work of Israeli artists and thinkers,[citation needed] such as Dor Guez's 2009–2010 exhibit Georgeopolis at the Petach Tikva art museum.[72]

Demographics

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the population of Lod in 2010 was 69.5 thousand people.[73]

Education

According to CBS, 38 schools and 13,188 pupils are in the city. They are spread out as 26 elementary schools and 8,325 elementary school pupils, and 13 high schools and 4,863 high school pupils. About 52.5% of 12th-grade pupils were entitled to a matriculation certificate in 2001.

Economy

The airport and related industries are a major source of employment for the residents of Lod. A Jewish Agency Absorption Centre (the main type of facility for handling Jewish immigrants arriving in Israel) is also located in Lod. According to CBS figures for 2000, 23,032 people were salaried workers and 1,405 were self-employed. The mean monthly wage for a salaried worker was NIS 4,754, a real change of 2.9% over the course of 2000. Salaried men had a mean monthly wage of NIS 5,821 (a real change of 1.4%) versus NIS 3,547 for women (a real change of 4.6%). The mean income for the self-employed was NIS 4,991. About 1,275 people were receiving unemployment benefits and 7,145 were receiving an income supplement.

Archaeology

A well-preserved mosaic floor dating to the Roman period was excavated in 1996 as part of a salvage dig conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority and the Municipality of Lod, prior to widening HeHalutz Street. According to Jacob Fisch, executive director of the Friends of the Israel Antiquities Authority, a worker at the construction site noticed the tail of a tiger and halted work.[74] The mosaic was initially covered over with soil at the conclusion of the excavation for lack of funds to conserve and develop the site.[75] The mosaic is now part of the Lod Mosaic Archaeological Center.

The Lod Community Archaeology Program, which operates in ten Lod schools, five Jewish and five Israeli Arab, combines archaeological studies with participation in digs in Lod.[76]

Sports

The city's major football club, Hapoel Bnei Lod, plays in Liga Leumit (the second division). Its home is at the Lod Municipal Stadium. The club was formed by a merger of Bnei Lod and Rakevet Lod in the 1980s. Two other clubs in the city play in the regional leagues: Hapoel MS Ortodoxim Lod in Liga Bet and Maccabi Lod in Liga Gimel.

Hapoel Lod played in the top division during the 1960s and 1980s, and won the State Cup in 1984. The club folded in 2002. A new club, Hapoel Maxim Lod (named after former mayor Maxim Levy) was established soon after, but folded in 2007.

Notable residents

- Etti Ankri, singer

- DAM, a hip-hop group

- George Habash (1926–2008), founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

- Tamer Nafar, rapper

- Salim Tuama, footballer

- Rabbi Akiva, Talmudic sage

- Oshri Cohen, actor

- Eliezer ben Hurcanus, Talmudic sage

- Rabbi Tarfon, Talmudic sage

- Joshua ben Levi, Talmudic sage

- St George, Patron Saint of Beirut, Palestine, England, Russia, and Catalonia

Twin towns-sister cities

Lod is twinned with:

See also

References

- ^ "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ The Madaba Mosaic Map, Jerusalem 1954, 61–62

- ^ Yacobi, 2009, p. 29: "The occupation of Lydda by Israel in the 1948 war did not allow the realization of Pocheck's garden city vision. Different geopolitics and ideologies began to shape Lydda's urban landscape ... [and] its name was changed from Lydda to Lod, which was the region's biblical name."; also see Pearlman, Moshe and Yannai, Yacov. Historical sites in Israel. Vanguard Press, 1964, p. 160. For the Hebrew name being used by inhabitants before 1948, see A Cyclopædia of Biblical literature: Volume 2, by John Kitto, William Lindsay Alexander. p. 842 ("... the old Hebrew name, Lod, which had probably been always used by the inhabitants, appears again in history."); And Lod (Lydda), Israel: from its origins through the Byzantine period, 5600 B.C.E.-640 C.E., by Joshua J. Schwartz, 1991, p. 15 ("the pronunciation Lud began to appear along with the form Lod")

- ^ Shapira, Anita, “Politics and Collective Memory: the Debate Over the 'New Historians' in Israel,” History and Memory 7 (1) (Spring 1995), pp. 9ff, 12–13, 16–17.

- ^ Blumenthal, 2013, p. 420

- ^ a b c d M. Sharon, s.v. "Ludd," Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed. Leiden: Brill, 1983, vol. 5, pp. 798-803. ISBN 978-90-04-07164-3.

- ^ Morris, 2004, pp. 414-461.

- ^ https://jerusaleminstitute.org.il/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/PUB_505_facts-and-trends_eng_2019_web.pdf, p. 18.

- ^ Exell, J. S. and Spencer-Jones, H. (eds), Pulpit Commentary on 1 Chronicles 8, accessed 8 February 2020

- ^ Bible Dictionary, "Lydda"

- ^ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, "Lod; Lydda"

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 216

- ^ "Lod," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009. "And it came to pass, as Peter passed throughout all quarters, he came down also to the saints which dwelt at Lydda," Acts 9:32–38

- ^ "Signs of the Appearance of the Dajjal". Missionislam.com. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ^ Schwartz, Joshua J. Lod (Lydda), Israel: from its origins through the Byzantine period, 5600 B.C.-640 A.D.. Tempus Reparatum, 1991, p. 39.

- ^ a b "Excursions in Terra Santa". Franciscan Cyberspot. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ Rozenfeld, 2010, p. 52

- ^ a b "Lod," Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ^ Gilbert, Martin. Dearest Auntie Flori: The Story of the Jewish People. New York: Harper Collins 2002, p. 82; also see Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 14:208

- ^ a b c d Lydda Catholic-hierarchy.org

- ^ Josephus, "Jewish War", I, xi, 2; "Antiquities", XIV xii, 2–5.

- ^ Michael Avi-Yonah, s.v. "Lydda," Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- ^ Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions, ed. Eric Orlin

- ^ Holder, 1986, p. 52

- ^ Ta'anit ii. 10; Yer. Ta'anit ii. 66a; Yer. Meg. i. 70d; R. H. 18b

- ^ Pes. 50a; B. B. 10b; Eccl. R. ix. 10

- ^ Cecil Roth, Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1972, p. 619.

- ^ Smallwood, 2001, p. 241

- ^ Yoram Tsafrir, Leah Di Segni, Judith Green, Tabula Imperii Romani Iudaea-Palestina: Eretz Israel in the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods; Maps and Gazetteer, p. 171. Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994. ISBN 978-965-208-107-0

- ^ Frenkel, Sheera and Low, Valentine. "Why Lod, the other land of St George, isn't for the faint-hearted", The Times, April 23, 2009.

- ^ Donner, Herbert (1995). The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide. Palaestina antiqua (7) (2nd print ed.). Kampen: Kok Pharos. p. 54. ISBN 90-390-0011-5. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 28

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 303

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 308

- ^ Le Strange, 1890 p. 493

- ^ Official Website Archived 2015-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Pringle, 1998, p. 11

- ^ Le Strange, 1890, p. 494

- ^ a b c d e Petersen, 2001, p. 203

- ^ Moudjir ed-dyn, 1876, Sauvaire (translation), pp. 210-213

- ^ al-Ẓāhirī, 1894, pp. 118-119

- ^ Singer, 2002, p.49

- ^ Petersen, 2005, p. 131

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 154

- ^ Karmon, 1960, p. 171

- ^ Thomson, 1859, pp. 292-3

- ^ a b Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 252

- ^ a b c d Shahin, 2005, p. 260

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, p. 21

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 46

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 21

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- ^ "Lod," 2 January 1949, IS archive Gimel/5/297 in Yacobi, 2009, p. 31.

- ^ a b Monterescu and Rabinowitz, 2012, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Sa'di and Abu-Lughod, 2007, pp. 91-92.

- ^ For one account, interspersed with interviews with IDF soldiers, see Ari Shavit, My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2013, pp. 99–132.

- ^ Tal, 2004, p. 311.

- ^ Sefer Hapalmah ii (The Book of the Palmah), p. 565; and KMA-PA (Kibbutz Meuhad Archives – Palmah Archive). Quoted in Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987.

- ^ Morris, 2004, p. 205 Morris writes: "[...] dozens of unarmed detainees in the mosque and church in the centre of the town were shot and killed."

- ^ The figure comes from Bechor Sheetrit, the Israeli Minister for Minority Affairs at the time, cited in Yacobi, 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Spiro Munayyer, The Fall of Lydda( اللد لن تقع), Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Summer, 1998), pp. 80–98. See also Yitzhak Rabin's diaries, quoted here [1].

- ^ Holmes et al., 2001, p. 64.

- ^ Morris, Benny "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948," Middle East Journal 40 (1986) p. 88.

- ^ For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing," see, for example, Pappé 2006.

- On whether what occurred in Lydda and Ramle constituted ethnic cleansing:

- Morris 2008, p. 408: "although an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed during critical months, transfer never became a general or declared Zionist policy. Thus, by war's end, even though much of the country had been 'cleansed' of Arabs, other parts of the country—notably central Galilee—were left with substantial Muslim Arab populations, and towns in the heart of the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa, were left with an Arab minority."

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Schwartzwald 2012, p. 63: "The facts do not bear out this contention [of ethnic cleansing]. To be sure, some refugees were forced to flee: fifty thousand were expelled from the strategically located towns of Lydda and Ramle ... But these were the exceptions, not the rule, and ethnic cleansing had nothing to do with it."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107: "The explusion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- ^ Hoffman, Carl (16 December 2008). "Lod: In need of a major makeover". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2009-06-02.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Yacobi, 2009, p. 29.

- ^ "Polishing a Lost Gem to Dazzle Tourists." New York Times. July 8, 2009.

- ^ Ganei Ya'ar in Lod[permanent dead link] The Jerusalem Post, 7 February 2008

- ^ Pulled Apart. The Economist. 2010-10-14.

- ^ Ron Friedman, Pushing for a better tomorrow in 8,000-year-old Lod, The Jerusalem Post, 8 April 2010. Accessedd 2020-03-25.

- ^ Neta Halperin, There's Art Outside of Tel Aviv, You Just Have to Look, Haaretz, 3 April 2012, accessedd 2020-03-25

- ^ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics Annual Report 2010.

- ^ Lod Mosaic tells nearly 2,000-year-old story from ancient Israel

- ^ Lod mosaic

- ^ Community Based Archaeology at Khan el-Hilu, Lod, Israel

- ^ "Piatra Neamţ – Twin Towns". Piatra Neamţ. Archived from the original on 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Blumenthal, M. (2013). Goliath: Life and Loathing in Greater Israel. Nation Books. ISBN 1568586345. - Profile at Google Books

- Conder, C. R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dauphin, Claudine (1998). La Palestine byzantine, Peuplement et Populations. BAR International Series 726 (in French). Vol. III : Catalogue. Oxford: Archeopress. ISBN 0-860549-05-4.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Gorzalczany, Amir; et al. (2016-05-09). "Lod, the Lod Mosaic" (128). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale. (p. 392)

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Holder, Meir (1986). History of the Jewish People From Yavne to Pumbedisa. Mesorah Publications. ISBN 089906499X.

- Holmes, R.; Strachan, H.; Bellamy, C.; Bicheno, Hugh (2001). The Oxford companion to military history (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198662092.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Monterescu, Daniel; Rabinowitz, Dan (2012). Mixed towns, trapped communities: historical narratives, spatial dynamics, gender relations and cultural encounters in Palestinian-Israeli towns (Illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 1409487466.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-00967-7.

- Moudjir ed-dyn (1876). Sauvaire (ed.). Histoire de Jérusalem et d'Hébron depuis Abraham jusqu'à la fin du XVe siècle de J.-C. : fragments de la Chronique de Moudjir-ed-dyn.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2001). A Gazetteer of Buildings in Muslim Palestine (British Academy Monographs in Archaeology). Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-727011-0.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 1841718211.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39037 0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. (pp.49 −55)

- Rozenfeld, Ben Tsiyon (2010). Torah Centers and Rabbinic Activity in Palestine, 70–400 CE: History and Geographic Distribution. BRILL. ISBN 9004178384.

- Sa'di, A. H.; Abu-Lughod, L. (2007). Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the claims of memory (Illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13579-5.

- Shahin, Mariam (2005). Palestine: A Guide. Interlink Books. ISBN 156656557X.

- Singer, A. (2002). Constructing Ottoman Beneficence: An Imperial Soup Kitchen in Jerusalem. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5352-9.

- Smallwood, E. M. (2001). The Jews under Roman rule: From Pompey to Diocletian: A Study in Political Relations. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-0-391-04155-4.

- Tal, D. (2004). War in Palestine, 1948: Strategy and diplomacy. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5275-7.

- Thomson, W. M. (1859). The Land and the Book: Or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery, of the Holy Land. Vol. 2 (1 ed.). New York: Harper & brothers.

- Yacobi, Haim (2009). Goliath:The Jewish-Arab City: Spatio-politics in a mixed community. Routledge. ISBN 1134065841.

- al-Ẓāhirī, Khalīl Ibn Shāhīn, Ghars al-Dīn Khalīl ibn Shāhīn (1894). Zoubdat kachf el-mamâlik: tableau politique et administratif de l'Égypte. E. Leroux.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- City council (in Hebrew)

- al-Lydd Palestine Remembered

- Lydda (Lod), Jewish Agency for Israel

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons