List of examples of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution — the repeated evolution of similar traits in multiple lineages which all ancestrally lack the trait — is rife in nature, as illustrated by the examples below. The ultimate cause of convergence is usually a similar evolutionary biome, as similar environments will select for similar traits in any species occupying the same ecological niche, even if those species are only distantly related. In the case of cryptic species, it can create species which are only distinguishable by analysing their genetics. Unrelated organisms often develop analogous structures by adapting to similar environments.

In animals

Mammals

- Several groups of ungulates have independently reduced or lost side digits on their feet, often leaving one or two digits for walking. That name comes from their hooves, which have evolved from claws several times. Among familiar animals, horses have one walking digit and domestic bovines two on each foot. Various other land vertebrates have also reduced or lost digits.[2]

- Similarly, laurasiathere perissodactyls and afrothere paenungulates have several features in common, to the point of there being no obvious distinction among basal taxa of both groups.[3]

- The pronghorn of North America, while not a true antelope and only distantly related to them, closely resembles the true antelopes of the Old World, both behaviorally and morphologically. It also fills a similar ecological niche and is found in the same biomes.[4]

- Members of the two clades Australosphenida and Theria evolved tribosphenic molars independently.[5]

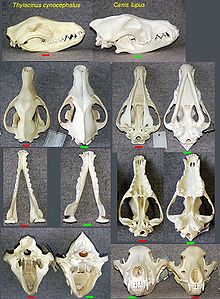

- The marsupial thylacine (Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf) had many resemblances to placental canids.[6]

- Several mammal groups have independently evolved prickly protrusions of the skin – echidnas (monotremes), the insectivorous hedgehogs, some tenrecs (a diverse group of shrew-like Madagascan mammals), Old World porcupines (rodents) and New World porcupines (another biological family of rodents). In this case, because the two groups of porcupines are closely related, they would be considered to be examples of parallel evolution; however, neither echidnas, nor hedgehogs, nor tenrecs are close relatives of the Rodentia. In fact, the last common ancestor of all of these groups was a contemporary of the dinosaurs.[7] The eutriconodont Spinolestes that lived in the Early Cretaceous Period represents an even earlier example of a spined mammal, unrelated to any modern mammal group.

- Cat-like sabre-toothed predators evolved in three distinct lineages of mammals – carnivorans like the sabre-toothed cats, and nimravids ("false" sabre-tooths), the sparassodont family Thylacosmilidae ("marsupial" sabre-tooths), the gorgonopsids and the creodonts also developed long canine teeth, but with no other particular physical similarities.[8]

- A number of mammals have developed powerful fore claws and long, sticky tongues that allow them to open the homes of social insects (e.g., ants and termites) and consume them (myrmecophagy). These include the four species of anteater, more than a dozen armadillos, eight species of pangolin (plus fossil species), eight species of the monotreme (egg-laying mammals) echidna (plus fossil species), the Fruitafossor of the Late Jurassic, the marsupial numbat, the African aardvark, the aardwolf, and possibly also the sloth bear of South Asia, all unrelated.[9]

- Marsupial koalas of Australia have evolved fingerprints, indistinguishable from those of non-related primates, such as humans.[10]

- The Australian honey possums acquired a long tongue for taking nectar from flowers, a structure similar to that of butterflies, some moths, and hummingbirds, and used to accomplish the same task.[11]

- Marsupial sugar glider and squirrel glider of Australia are like the placental flying squirrel. Both lineages have independently developed wing-like flaps (patagia) for leaping from trees, and big eyes for foraging at night.[12]

- The North American kangaroo rat, Australian hopping mouse, and North African and Asian jerboa have developed convergent adaptations for hot desert environments; these include a small rounded body shape with large hind legs and long thin tails, a characteristic bipedal hop, and nocturnal, burrowing and seed-eating behaviours. These rodent groups fill similar niches in their respective ecosystems.[13]

- Opossums and their Australasian cousins have evolved an opposable thumb, a feature which is also commonly found in the non-related primates.[14]

- The marsupial mole has many resemblances to the placental mole.[15]

- Marsupial mulgaras have many resemblances to placental mice.[16]

- Planigale has many resemblances to the deer mouse.[17]

- The marsupial Tasmanian devil has many resemblances to the placental hyena or a wolverine. Similar skull morphology, large canines and crushing carnasial molars.[18]

- Marsupial kangaroos and wallabies have many resemblances to the maras (a large rodent from the cavy family (Caviidae)), rabbits and hares (lagomorphs).[19]

- The marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, had retractable claws, the same way the placental felines (cats) do today.[20]

- Microbats, toothed whales and shrews developed sonar-like echolocation systems used for orientation, obstacle avoidance and for locating prey. Modern DNA phylogenies of bats have shown that the traditional suborder of echolocating bats (Microchiroptera) is not a true clade, and instead some echolocating bats are more related to non-echolocating Old World fruit bats than to other echolocating species. The implication is that echolocation in at least two lineages of bats, Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera has evolved independently or been lost in Old World fruit bats.[21][22]

- Echolocation in bats and whales also both necessitate high frequency hearing. The protein prestin, which confers high hearing sensitivity in mammals, shows molecular convergence between the two main clades of echolocating bats, and also between bats and dolphins.[23][24] Other hearing genes also show convergence between echolocating taxa.[25] Recently the first genome-wide study of convergence was published, this study analysed 22 mammal genomes and revealed that tens of genes have undergone the same replacements in echolocating bats and ceteaceans, with many of these genes encoding proteins that function in hearing and vision.[26]

- Both the aye-aye lemur and the striped possum have an elongated finger used to get invertebrates from trees. There are no woodpeckers in Madagascar or Australia where the species evolved, so the supply of invertebrates in trees was large.[27]

- Castorocauda, a Jurassic Period mammal and beavers both have webbed feet and a flattened tail, but are not related.[28]

- Prehensile tails evolved in a number of unrelated species marsupial opossums, kinkajous, New World monkeys, tree-pangolins, tree-anteaters, porcupines, rats, skinks and chameleons, and the salamander Bolitoglossa.[29]

- Pig form, large-headed, pig-snouted and hoofs are independent in true pigs in Eurasia, peccaries in South America and the extinct entelodonts.[30]

- Tapirs and pigs look much alike, but tapirs are perissodactyls (odd-toed ungulates) and pigs are artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates).[31]

- Filter feeding: baleen whales like the humpback and blue whale (mammals), the whale shark and the basking shark separately, the manta ray, the Mesozoic bony fish Leedsichthys, and the early Paleozoic anomalocaridid Aegirocassis have separately evolved ways of sifting plankton from marine waters.[32]

- The monotreme platypus has what looks like a bird's beak (hence its scientific name Ornithorhynchus), but is a mammal.[33] It was thought that somebody had sewn a duck's beak onto the body of a beaver-like animal. Shaw even took a pair of scissors to the dried skin to check for stitches.[34] However, it is not structurally similar to a bird beak (or any "true" beak, for that matter), being fleshy instead of keratinous.

- Red blood cells in mammals lack a cell nucleus. In comparison, the red blood cells of other vertebrates have nuclei; the only known exceptions are salamanders of the genus Batrachoseps and fish of the genus Maurolicus.[35]

- Caniforms like skunks and raccoons in North and South America and feliforms such as mongoose and civets in Asia and Africa have both evolved to fill the niche of small to medium omnivore/insectivore on their side of the world. Some species of mongoose and civet can even spray their attacker with musk similar to the skunk and some civets have also independently evolved similar markings to the raccoon such as the African civet.[36]

- River dolphins of the three species that live exclusively in freshwater, live in different rivers: Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers of India, the Yangtze River of China, and the Amazon River. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequence analysis demonstrates the three are not related.[37]

- Mangabeys comprise three different genera of Old World monkeys. The genera Lophocebus and Cercocebus resemble each other and were once thought to be closely related, so much so that all the species were in one genus. However, it is now known that Lophocebus is more closely related to baboons, while the Cercocebus is more closely related to the mandrill.[38]

- Sperm whale and the microscopic copepods both use the same buoyancy control system.[39]

- The wombat is a marsupial that has many resemblances to the groundhog a placental rodent related to marmots, which are mostly related to squirrels.[40]

- The fossa of Madagascar looks like a small cat. Fossa have semiretractable claws. Fossa also has flexible ankles that allow it to climb up and down trees head-first, and also support jumping from tree to tree. Its classification has been controversial because its physical traits resemble those of cats, but is more closely related to the mongoose family, (Herpestidae) or most likely the family Malagasy carnivores family, (Eupleridae).[41][42]

- The raccoon dog of Asia looks like the raccoon of North America (hence its scientific name Procyonoides) due to its black face mask, stocky build, bushy appearance, and ability to climb trees. Despite their similarities, it is actually classified as part of the dog family, (Canidae).

- Gliders or passive flight has developed independently in flying squirrels, Australian marsupial, lizards, paradise tree snake, frogs, gliding ants and flying fish and the ancient volaticotherium that lived in the Jurassic Period looked like a flying squirrel, but is not an ancestor of squirrels.[43][44]

- Amynodontidae a family of extinct rhinoceroses that are thought to have looked and behaved like squat, aquatic, hippopotamuses.[45][46]

- Trichromatic color vision, separate blue, green and red vision, found only in a few mammals and came about independently in humans, Old World monkeys and the howler monkeys of the New World, and a few Australian marsupials. .[47][48]

- Ruminant forestomaches came about independently in: hoatzin bird and tree sloths of the Amazon, ruminant artiodactyls (deer, cattle), colobus monkeys of the Old World and some Macropodidae.[49][50]

- Adept metabolic water, acquiring water by fat combustion in xerocole desert animal and others came about independently in: camel, kangaroo rat, migratory birds must rely exclusively on metabolic water production while making non-stop flights and more.[51][52][53][54]

- Many aquatic mammals independently came to have adaptions to live in water; for example, dugongs and whales have similar-looking tail flukes.[citation needed] Unrelated herbivores and carnivores have adapted to marine and freshwater environments.

- Glyptodontidae, a family of extinct mammals related to armadillos, had a shell much like a tortoise or turtle. Pangolins have convergently evolved the same features.

- Megaladapis, a genus of extinct lemur, bears a great resemblance to an indri or a koala (hence its nickname "koala-lemur") due to their stocky build, tufted ears, and short stumpy tail.

- Palaeopropithecidae, a family of extinct lemurs, which are most likely related to the family Indriidae due to their morphology, have many similarities to sloths due to their appearance and behaviour, such as long arms, hooked fingers, and slow moving, giving them the nickname "sloth-lemurs".

- Archaeolemuridae, another family of extinct lemurs, which are also most likely related to the family Indriidae, have many similarities to monkeys and baboons due to their body plans, which are both adopted to arboreal and terrestrial lifestyle, giving them the nickname "monkey-lemurs" or "baboon-lemurs".

- South American fox looks like a fox, but it not. [55]

Prehistoric reptiles

- Pterosaurian pycnofibrils strongly resemble mammalian hair, but are thought to have evolved independently.[56]

- Ornithischian (bird-hipped) dinosaurs had a pelvis shape similar to that of birds, or avian dinosaurs, which evolved from saurischian (lizard-hipped) dinosaurs.[57]

- The Heterodontosauridae evolved a tibiotarsus which is also found in modern birds. These groups aren't closely related.[58]

- Ankylosaurs and glyptodont mammals both had spiked tails.[59]

- The sauropods and giraffes independently evolved long necks.[60]

- The horned snouts of ceratopsian dinosaurs like Triceratops have also evolved several times in Cenozoic mammals: rhinos, brontotheres, Arsinoitherium, and Uintatherium.[61]

- Billed snouts on the duck-billed dinosaurs hadrosaurs strikingly convergent with ducks and duck-billed platypus.[62]

- Ichthyosaurs a marine reptile of the Mesozoic era looked strikingly like dolphins.[63]

- Beaks are independent in ceratopsian dinosaurs like Triceratops, birds, turtles, and cephalopods like squid and octopus.[64]

- The Pelycosauria and the Ctenosauriscidae bore striking resemblance to each other because they both had a sail-like fin on their back. The pelycosaurs are more closely related to mammals while the ctenosauriscids are closely related to pterosaurs and dinosaurs. Also, the spinosaurids had sail-like fins on their backs, when they were not closely related to either.[65][66]

- Also, Acrocanthosaurus and Ouranosaurus, which are not closely related to either pelycosaurs, ctenosauriscids or spinosaurids, also had similar, but thicker, spines on their vertebrae, and thus have humps, like the unrelated, mammalian camels and bison.[67]

- Noasaurus, Baryonyx, and Megaraptor, all unrelated, all had an enlarged hand claw that were originally thought to be placed on the foot, as in dromaeosaurs. A similarly modified claw (or in this case, finger) is on the hand of Iguanodon.[68]

- The ornithopods had feet and beaks that resembled that of birds, but are only distantly related.[69]

- Three groups of dinosaurs, the Tyrannosauridae, Ornithomimosauria, and the Troodontidae, all evolved an arctometatarsus, independently.[70]

- Some placodonts (like Cyamodus, Psephoderma, Henodus and especially Placochelys) bear striking resemblance to sea turtles (and turtles in general) in terms of size, shell, beak, mostly toothless jaws, paddle-shaped limbs and possibly other adaptations for aquatic lifestyle.[71]

- Cretaceous Hesperornithes were much like modern diving ducks, loons and grebes. Hesperornithes had the same lobed feet like grebes, with the hind legs very far back, that most likely they could not walk on land.[72][73]

Extant reptiles

- The thorny devil (Moloch horridus) is similar in diet and activity patterns to the Texas horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum), although the two are not particularly closely related.[citation needed]

- Modern crocodilians resemble prehistoric phytosaurs, champsosaurs, certain labyrinthodont amphibians, and perhaps even the early whale Ambulocetus. The resemblance between the crocodilians and phytosaurs in particular is quite striking; even to the point of having evolved the graduation between narrow- and broad-snouted forms, due to differences in diet between particular species in both groups.[74]

- The body shape of the prehistoric fish-like reptile Ophthalmosaurus was similar to those of other ichthyosaurians, dolphins (aquatic mammals), and tuna (scombrid fish).[75]

- Death adders strongly resemble true vipers, but are elapids.[76]

- The glass snake is actually a lizard but is mistaken as a snake .[77]

- Large tegu lizards of South America have converged in form and ecology with monitor lizards, which are not present in the Americas.[78]

- Legless lizards such as Pygopodidae are snake-like lizards that are much like true snakes.[79]

- Anole lizards, with populations on isolated islands, are one of the best examples of both adaptive radiation and convergent evolution.[80]

- The Asian sea snake Enhydrina schistosa (beaked sea snake) looks just like the Australian sea snake Enhydrina zweifeli, but in fact is not related.[81]

- The emerald tree boa and the green tree python are from two different genera, yet are very much alike.[40]

Avian

- Ostriches are large ratites specialised to cursoriality, having lost the first and second toes. Eogruids and geranoidids were crane relatives that also specialised for cursoriality in the same way, showing a reduction in the second toe's trochea, culminating in its disappearance in more derived taxa.

- The little auk of the north Atlantic (Charadriiformes) and the diving-petrels of the southern oceans (Procellariiformes) are remarkably similar in appearance and habits.[82]

- The Eurasian magpie is a corvid, the Australian magpie is not.[83]

- Penguins in the Southern Hemisphere evolved similarly to flightless wing-propelled diving auks in the Northern Hemisphere: the Atlantic great auk and the Pacific mancallines.[84]

- Vultures are a result of convergent evolution: both Old World vultures and New World vultures eat carrion, but Old World vultures are in the eagle and hawk family (Accipitridae) and use mainly eyesight for discovering food; the New World vultures are of obscure ancestry, and some use the sense of smell as well as sight in hunting. Birds of both families are very big, search for food by soaring, circle over sighted carrion, flock in trees, and have unfeathered heads and necks.[85]

-

Nubian vulture, an Old World vulture

-

Turkey vulture, a New World vulture

-

Hummingbird, a New World bird, with a sunbird, an Old World bird

-

Comparison of an ostrich and the eogruid Ergilornis (to scale), combined with the closest living relatives, a tinamou and a trumpeter respectively (not to scale).

- Hummingbirds resemble sunbirds. The former live in the Americas and belong to an order or superorder including the swifts, while the latter live in Africa and Asia and are a family in the order Passeriformes. Also the nectar-feeding Hawaiian honeycreepers resemble the two and differs from other honeycreeper.[86][87]

- Flightlessness has evolved in many different birds independently. However, taking this to a greater extreme, the terror birds, Gastornithiformes and dromornithids (ironically all extinct) all evolved the similar body shape (flightlessness, long legs, long necks, big heads), yet none of them were closely related. They also share the trait of being giant, flightless birds with vestigial wings, long legs, and long necks with the ratites, although they are not related.[88][89]

- Certain longclaws (Macronyx) and meadowlarks (Sturnella) have essentially the same striking plumage pattern. The former inhabit Africa and the latter the Americas, and they belong to different lineages of Passerida. While they are ecologically quite similar, no satisfying explanation exists for the convergent plumage; it is best explained by sheer chance.[90]

- Resemblances between swifts and swallows is due to convergent evolution. The chimney swift was originally identified as chimney swallow (Hirundo pelagica) by Carl Linnaeus in 1758, before being moved to the swift genus Chaetura by James Francis Stephens in 1825.[91]

- Downy woodpecker and hairy woodpecker look almost the same, as do some 'Chrysocolaptes and Dinopium flamebacks, the smoky-brown woodpecker and some Veniliornis species, and other Veniliornis species and certain "Picoides" and Piculus. In neither case are the similar species particularly close relatives.[92]

- Many birds of Australia, like wrens and robins, look like Northern Hemisphere birds but are not related.[93]

- Oilbird like microbats and toothed whales developed sonar-like echolocation systems used for locating prey.[94]

- The brain structure, forebrain, of hummingbirds, songbirds, and parrots responsible for vocal learning (not by instinct) is very similar. These types of birds are not closely related.[95]

- Seriemas and secretary birds very closely resemble the ancient dromaeosaurid and troodontid dinosaurs. Both have evolved a retractable sickle-shaped claw on the second toe of each foot, both have feathers, and both are very similar in their overall physical appearance and lifestyle.[96]

- Migrating birds like, Swainson's thrushes can have half the brain sleep with the other half awake. Dolphins, whales, Amazonian manatee and pinnipeds can do the same. Called Unihemispheric slow-wave sleep.[97]

- Brood parasitism, laying eggs in the nests of birds of other species, happens in types of birds that are not closely related.[98]

Fish

- Fish that swim by using an elongated fin along the dorsum, ventrum, or in pairs on their lateral margins (such as Oarfish, Knifefish, Cephalopods) have all come to the same ratio of amplitude to wavelength of fin undulation to maximize speed, 20:1.[99]

- Mudskippers exhibit a number of adaptations to semi-terrestrial lifestyle which are also usually attributed to Tiktaalik: breathing surface air, having eyes positioned on top of the head, propping up and moving on land using strong fins.[100]

-

Tiktaalik roseae - artistic interpretation. Neil Shubin, suggests the animal could prop up on its fins to venture onto land, though many palaeonthologists reject this idea as outdated

-

Boleophthalmus boddarti - a mudskipper which is believed to share some features with extinct fishapods in terms of adaptations to terrestrial habitats

-

A group of mudskippers coming ashore - they use pectoral fins to prop up and move on land. Some scientists believe Tiktaalik to have acted likewise

- Goby dorsal finned like the lumpsuckers, yet they are not related.

- The Rhenanids became extinct over 200 million years before the first stingrays evolved, yet they share quite a similar appearance.

- Sandlance fish and chameleons have independent eye movements and focusing by use of the cornea.[101]

- Acanthurids and mbuna are both aggressive, brightly colored fish that feed principally on aufwuchs, although the former is found only in marine environments, while the latter is only found in freshwater Lake Malawi.

- Cichlids of South America and the "sunfish" of North America are strikingly similar in morphology, ecology and behavior.[102]

- The peacock bass and largemouth bass are excellent examples. The two fishes are not related, yet are very similar. Peacock bass are native of South America and is a Cichla. While largemouth bass are native to Southern USA states and is a sunfish.[103] others will surely be described (but see the results based on DNA data[104]).

- The antifreeze protein of fish in the arctic and Antarctic, came about independently.[105] AFGPs evolved separately in notothenioids and northern cod. In notothenioids, the AFGP gene arose from an ancestral trypsinogen-like serine protease gene.[106]

- Electric fish: electric organs and electrosensory systems evolved independently in South American Gymnotiformes and African Mormyridae.[107]

- Eel form are independent in the North American brook lamprey, neotropical eels, and the African spiny eel.[108]

- Stickleback fish, there is widespread convergent evolution in sticklebacks.[109]

- Flying fish can fly up to 400 m (1,300 ft) at speeds of more than 70 kilometres per hour (43 mph) at a maximum altitude of more than 6 m (20 ft), much like other flying birds, bats and other gliders.[110]

- Extinct fish of the family Thoracopteridae, like Thoracopterus or Potanichthys, were similar to modern flying fish (gliding ability thanks to enlarged pair of pectoral fins and a deeply forked tail fin) which is not, however, considered to be their descendant.[111]

- The cleaner wrasse Labroides dimidiatus of the Indian Ocean is a small, longitudinally-striped black and bright blue cleaner fish, just like the cleaner goby Elacatinus evelynae of the western Atlantic.[112]

- The fish of the now discredited genus Stylophthalmus are only distantly related, but their larvae (Stomiiformes and Myctophiformes) have developed similar, stalked eyes.[113] (see: Stylophthalmine trait)

- Sawfish, a ray and unrelated sawshark have sharp transverse teeth for hunting.[114]

- Underwater camouflage is found independently in many fish like: leafy seadragon (large part of its body is just for camouflage, pygmy seahorse, leaf scorpionfish, flounder, peacock flounder. Some have active camouflage that changes with need.[115]

- Distraction eye, many fish have spot on the tail to fool prey. Prey are not sure which is the front, the direction of travel.[116]

- Gills appear in unrelated fish, some amphibians, some crustacean, aquatic insects and some mollusk, like freshwater snails, squid, octopus.[117]

-

Cleaner wrasse Labroides dimidiatus servicing a Bigeye squirrelfish

-

Caribbean cleaning goby Elacatinus evelynae

Amphibians

- Plethodontid salamanders and chameleons have evolved a harpoon-like tongue to catch insects.[118]

- The Neotropical poison dart frog and the Mantella of Madagascar have independently developed similar mechanisms for obtaining alkaloids from a diet of mites and storing the toxic chemicals in skin glands. They have also independently evolved similar bright skin colors that warn predators of their toxicity (by the opposite of crypsis, namely aposematism).[119]

- Caecilians are lissamphibians that secondarily lost their limbs, superficially resembling snakes and legless lizards.[120]

- Oldest known tetrapods (semi-aquatic Ichthyostegalia) resembled giant salamanders (body plan, lifestyle), though they are considered to be only distantly related.[121]

- A number of amphibians such as lungless salamanders and the Bornean flat-headed frog separately evolved lunglessness.[122]

-

Elginerpeton pacheni, the oldest known tetrapod

-

Andrias japonicus, a giant salamander which resembles first tetrapods

- Ambystoma mexicanum, an extant species, is difficult to tell apart from Permian Branchiosaurus[123]

-

Branchiosaurus, a Permian genus

-

Mexican salamander (axolotl), extant

Arthropods

- The smelling organs of the terrestrial coconut crab are similar to those of insects.[124]

- In an odd cross-phyla example, an insect, the hummingbird hawk-moth (Macroglossum stellatarum), also feeds by hovering in front of flowers and drinking their nectar in the same way as hummingbirds and sunbirds.[125]

- Pill bugs and pill millipedes have evolved not only identical defenses, but are even difficult tell apart at a glance.[126] There is also a large ocean version: the giant isopod.[127]

- Silk: Spiders, silk moths, larval caddis flies, and the weaver ant all produce silken threads.[128]

- The praying mantis body type – raptorial forelimb, prehensile neck, and extraordinary snatching speed - has evolved not only in mantid insects but also independently in neuropteran insects Mantispidae.[129]

- Gripping limb ends have evolved separately in scorpions and in some decapod crustaceans, like lobsters and crabs. These chelae or claws have a similar architecture: the next-to-last segment grows a projection that fits against the last segment.[130]

- Agriculture: Some kinds of ants, termites, and ambrosia beetles have for a long time cultivated and tend fungi for food. These insects sow, fertilize, and weed their crops. A damselfish also takes care of red algae carpets on its piece of reef; the damselfish actively weeds out invading species of algae by nipping out the newcomer.[131]

- Slave-making behavior has evolved several times independently in the ant subfamilies Myrmicinae and Formicinae,[132][133] and more than ten times in total in ants.[134]

- Proleg a fleshy leg on many larvae of insects is found in all the orders in which they appear, formed independently of each order by convergent evolution.[135]

- Parasitoid use of viruses, parasitoid wasps lay their eggs inside host caterpillars, to keep the caterpillar's immune system from killing the egg, a virus is also "laid" with the eggs. Two unrelated wasps use this trick.[136]

- Short-lived breeders, species that are in the juvenile phase for most of their lives. The adult lives are so short most do not have working mouth parts. Unrelated species: cicada, mayflies, some flies, dragonfly, silk moths, and some other moths.[137][138]

- Katydids and frogs both make loud sounds with a sound-producing organs to attract females for mating .[139]

- Camouflage of two kinds: twig-like camouflage independently in walking sticks and the larvae of some butterflies and moths; leaf camouflage is found independently in some praying mantids and winged moths.

- Dipteran flies and Strepsiptera insects independently came up with whirling drumsticks halteres that are used like gyroscopes in flight.[140]

- Carcinisation, in which a crustacean evolves into a crab-like form from a non-crab-like form. The term was introduced into evolutionary biology by L. A. Borradaile, who described it as "one of the many attempts of Nature to evolve a crab".[141]

Molluscs

- Bivalves and the gastropods in the family Juliidae have very similar shells.[142]

- There are limpet-like forms in several lines of gastropods: "true" limpets, pulmonate siphonariid limpets and several lineages of pulmonate freshwater limpets.[143][144]

- Cephalopod (like in octopuses & squid) and vertebrate eyes are both lens-camera eyes with much overall similarity, yet are very unrelated species. A closer examination reveals some differences like: embryonic development, extraocular muscles, how many lens parts, etc.[145][146]

- Swim bladders: Buoyant bladders independently evolved in fishes, the tuberculate pelagic octopus, and siphonophores such as the Portuguese man o' war.[147]

- Bivalves and brachiopods independently evolved paired hinged shells for protection. However, the anatomy of their soft parts is very dissimilar, which is why molluscs and brachiopods are put into different phyla.[148]

- Jet propulsion in squids and in scallops: these two groups of mollusks have very different ways of squeezing water through their bodies in order to power rapid movement through a fluid. (Dragonfly larvae in the aquatic stage also use an anal jet to propel them, and jellyfish have used jet propulsion for a very long time.). Sea hares (gastropod molluscs) employ a similar means of jet propulsion, but without the sophisticated neurological machinery of cephalopods they navigate somewhat more clumsily.[149][150] tunicates (such as salps),[151][152] and some jellyfish[153][154][155] also employ jet propulsion. The most efficient jet-propelled organisms are the salps,[151] which use an order of magnitude less energy (per kilogram per metre) than squid.[156]

Other

- The notochords in chordates are like the stomochords in hemichordates.[157]

- Elvis taxon in the fossil record developed a similar morphology through convergent evolution.[158]

- Venomous sting: To inject poison with a hypodermic needle, a sharppointed tube, has shown up independently 10+ times: jellyfish, spiders, scorpions, centipedes, various insects, cone shell, snakes, some catfish, stingrays, stonefish, the male duckbill platypus, Siphonophorae and stinging nettles plant.[159]

- Bioluminescence: Symbiotic partnerships with light-emitting bacteria developed many times independently in deep-sea fish, jellyfish, fireflies, Rhagophthalmidae, Pyrophorus beetles, pyrosome, Mycena, Omphalotus nidiformis mushrooms, Vargula hilgendorfii, Quantula striata snail, googly-eyed glass squid, stiptic fungus, Noctiluca scintillans, Pyrocystis fusiformis, vargulin, sea pen, ostracod, Siphonophorae and glow worms. Bioluminescence is also produced by some animals directly. [160][161]

- Parthenogenesis: Some lizards and insects have independent the capacity for females to produce live young from unfertilized eggs. Some species are entirely female.[162]

- Extremely halophile archaeal family Halobacteriaceae and the extremely halophilic bacterium Salinibacter ruber both can live in high salt environment.[163]

- In the evolution of sexual reproduction and origin of the sex chromosome: Mammals, females have two copies of the X chromosome (XX) and males have one copy of the X and one copy of the Y chromosome (XY). In birds it is the opposite, with males have two copies of the Z chromosome (ZZ) and females have one copy of the Z and one copy of the W chromosome (ZW).[164]

- Multicellular organisms arose independently in brown algae (seaweed and kelp), plants, and animals.[165]

- Origins of teeth have happened at least two times.[166]

- Winged flight is found in unrelated species: birds, bats (mammal), insects, pterosaur and Pterodactylus (reptiles). Flying fish do not fly, but are very good at gliding flight.[167]

- Hummingbird, dragonfly and hummingbird hawk-moth can hover and fly backwards.[168]

- Neuroglobins are found in vertebrate neurons, (deuterostomes), and are found in the neurons of unrelated protostomes, like photosynthesis acoel and jelly fish.[169]

- Siphonophorae and Praya dubia resemble and act like jellyfish, but are Hydrozoa, a colony of specialized minute individuals called zooids.[170][171] Salp, a Chordata, also is very much like jellyfish, yet completely different.[172]

- Eusociality colonies in which only one female (queen) is reproductive and all other are divided into a castes system, all work together in a coordinate system. This system is used in many unrelated animals: ants, bees, and wasps, termites, naked mole-rat, Damaraland mole-rat, Synalpheus regalis shrimp, certain beetles, some gall thrips and some aphids.[173]

- Oxygenate blood came about in unrelated animals groups: vertebrates use iron (hemoglobin) and crustaceans and many mollusks use copper (hemocyanin).[174]

- Biomineralization the secrete protective shells or carapaces made out of organically made hard materials like mineral carbonates and organic chitins came about in unrelated species all at the same time during the cambrian Explosion in: mollusks, brachiopods, arthropods, bryozoans, echinoderms, tube worms.[175][a]

- Reef builders, a number of unrelated species of sea life build rocky like reefs: some types of bacteria make stromatolites, various sponges build skeletons of calcium carbonate, like: Archaeocyath sponges, and stromatoporoid sponges, corals, some anthozoan cnidarians, bryozoans, calcareous algae and some bivalves (rudist bivalves).[176][177][178]

- Magnetite for orientation, magnetically charged particles of magnetite for directional sensing have been found in unrelated species of salmon, rainbow trout, some butterflies and birds.[179]

- Hydrothermal vent adaptations like the use of bacteria housed in body flesh or in special organs, to the point they no long have mouth parts, have been found in unrelated hydrothermal vent species of mollusks and tube worms (like the giant tube worm.[180]

- Lichens are a partnerships of fungi and algae. Each "species" of lichen is make of different fungi and algae species, thus each has to come about independently.[181][182][183]

- Parental care came about independently in: mammals, most birds, some insects, some fish and crocodilians.[184][185]

- Regeneration, many different unrelated species can grow new limbs, tail or other body parts, if body parts are lost.[186][187]

- The Statocyst is a balance sensory receptor independently found in different organisms like: some aquatic invertebrates, including bivalves,[188] cnidarians,[189] echinoderms,[190] cephalopods,[191] and crustaceans.[192] Also found in single-cell ciliate. A similar structure is also found in Xenoturbella.[193]

- Hearing came about in many different unrelated species with the: Tympanal organ, Johnston's organ and mammals/bird ears. Also the simpler hearing found in reptiles, with only the stapes bone.

- Infrared vision is in many different unrelated species: Pit viper snakes (rattlesnakes), pythons, vampire bats, and wood-boring wasps and fire beetles.

In plants

- Leaves have evolved multiple times - see Evolutionary history of plants. They have evolved not only in land plants, but also in various algae, like kelp.[194]

- Prickles, thorns and spines are all modified plant tissues that have evolved to prevent or limit herbivory, these structures have evolved independently a number of times.[195]

- Stimulant toxins: Plants which are only distantly related to each other, such as coffee and tea, produce caffeine to deter predators.[196]

- The aerial rootlets found in ivy (Hedera) are similar to those of the climbing hydrangea (Hydrangea petiolaris) and some other vines. These rootlets are not derived from a common ancestor but have the same function of clinging to whatever support is available.[197]

- Flowering plants (Delphinium, Aerangis, Tropaeolum and others) from different regions form tube-like spurs that contain nectar. This is why insects from one place sometimes can feed on plants from another place that have a structure like the flower, which is the traditional source of food for the animal.[198]

- Some dicots (Anemone) and monocots (Trillium) in inhospitable environments are able to form underground organs such as corms, bulbs and rhizomes for reserving of nutrition and water until the conditions become better.

- Carnivorous plants: Nitrogen-deficient plants have in at least 7 distinct times become carnivorous, like: flypaper traps such as sundews and butterworts, spring traps-Venus fly trap, and pitcher traps in order to capture and digest insects to obtain scarce nitrogen.[199][200]

- Pitcher plants: The pitcher trap evolved independently in three eudicot lineages and one monocot lineage.[201][202]

- Similar-looking rosette succulents have arisen separately among plants in the families Asphodelaceae (formerly Liliaceae) and Crassulaceae.[203]

- The orchids, the birthwort family and Stylidiaceae have evolved independently the specific organ known as gynostemium, more popular as column.[204]

- The Euphorbia of deserts in Africa and southern Asia, and the Cactaceae of the New World deserts have similar modifications (see picture below for one of many possible examples).[205]

- Sunflower: some types of sunflower and Pericallis are due to convergent evolution.[206]

- Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a carbon fixation pathway that evolved in multiple plants as an adaptation to arid conditions.[207]

- C4 photosynthesis is estimated to have evolved over 60 times within plants,[208] via multiple different sequences of evolutionary events.[209] C4 plants use a different metabolic pathway to capture carbon dioxide but also have differences in leaf anatomy and cell biology compared to most other plants.

- Trunk, a single woody stem came about in unrelated plants: paleozoic tree forms of club mosses, horsetails, and seed plants.

- The marine animals sea lily crinoid, looks like a terrestrial palm tree.[210]

- Palm trees form are in unrelated plants: cycads (from Jurassic period) and older tree ferns.[211]

- Flower petals came about independently in a number of different plant lineages.[212]

- Bilateral flowers, with distinct up-down orientation, came about independently in a number of different plants like: violets, orchids and peas.[213][214]

- United petals, petals that unite into a single bell shape came about independently in blueberries, Ericaceae and other plants.[215]

- Hummingbird flowers are scentless tubular flowers that have independently came about in at least four plant families. They attract nectar-feeding birds like: hummingbirds, honey eaters, sunbirds. Remote Hawaii also has hummingbird flowers.[216]

- Carrion flower type flowers that smell like rotting meat have independently came about in: pawpaw (family Annonaceae), the giant Indonesian parasitic flower Rafflesia, and African milkweed (Stapelia gigantea).[217]

- Fruit that develops underground, after the upper part is pollinated the flower stalk elongates, arches downward and pushes into the ground, this has independently came about in: peanut, legume, Florida's endangered burrowing four o'clock and Africa's Cucumis humifructus.[218]

- Plant fruit the fleshy nutritious part of plants that animal dispense by eating independently came about in flowering plants and in some gymnosperms like: ginkgo and cycads.[219]

- Water transport systems, like vascular plant systems, with water conducting vessels, independently came about in horsetails, club mosses, ferns, and gymnosperms.[220]

- Wind pollination independently came about in pine trees, grasses, and wind pollinated flower.

- Wind dispersal of seeds independently came about in dandelions, milkweed, cottonwood trees, and others tufted seeds like, impatiens sivarajanii, all adapted for wind dispersal.[221]

- Hallucinogenic toxins independently came about in: peyotecactus, Ayahuasca vine, some fungi like psilocybin mushroom.[222]

- Plant toxins independently came about in: solauricine, daphnin, tinyatoxin, ledol, protoanemonin, lotaustralin, chaconine, persin and more.[223]

- Venus flytrap sea anemone is an Animalia and Venus flytrap plant. Both look and act the same.[224]

- Digestive enzymes independently came about in carnivorous plants and animals.[225]

In fungi

- There are a variety of saprophytic and parasitic organisms that have evolved the habit of growing into their substrates as thin strands for extracellular digestion. This is most typical of the "true" fungi, but it has also evolved in Actinobacteria (Bacteria), oomycetes (which are part of the stramenopile grouping, as are kelp), parasitic plants, and rhizocephalans (parasitic barnacles).[226][227][228]

- Slime molds are traditionally classified as fungi, but molecular-phylogeny work has revealed that most slime molds are not very close to Fungi proper and similar organisms, and that their slime-mold habit has originated several times. Mycetozoa (Amoebozoa), Labyrinthulomycetes (Stramenopiles), Phytomyxea and Guttulinopsis vulgaris[229] (Rhizaria), Acrasidae (Excavata), Fonticula alba (Opisthokonta), and Myxobacteria (Bacteria). Mycetozoa itself contains myxogastrids, dictyostelids, and protostelids, likely with separate origins, with protostelids themselves likely originating several times.[230][231][232]

- Specialized forms of osmotrophy are found in unrelated fungi and animals.[233]

In proteins, enzymes and biochemical pathways

Functional convergence

Here is a list of examples in which unrelated proteins have similar functions with different structure.

- The convergent orientation of the catalytic triad in the active site of serine and cysteine proteases independently in over 20 enzyme superfamilies.[234]

- The use of an N-terminal threonine for proteolysis.

- The existence of distinct families of carbonic anhydrase is believed to illustrate convergent evolution.

- The use of (Z)-7-dodecen-1-yl acetate as a sex pheromone by the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) and by more than 100 species of Lepidoptera.

- The biosynthesis of plant hormones such as gibberellin and abscisic acid by different biochemical pathways in plants and fungi.[235][236]

- The protein prestin that drives the cochlea amplifier and confers high auditory sensitivity in mammals, shows numerous convergent amino acid replacements in bats and dolphins, both of which have independently evolved high frequency hearing for echolocation.[23][24] This same signature of convergence has also been found in other genes expressed in the mammalian cochlea[25]

- The repeated independent evolution of nylonase in two different strains of Flavobacterium and one strain of Pseudomonas.

- The myoglobin from the abalone Sulculus diversicolor has a different structure from normal myoglobin but serves a similar function — binding oxygen reversibly. "The molecular weight of Sulculus myoglobin is 41kD, 2.5 times larger than other myoglobins." Moreover, its amino acid sequence has no homology with other invertebrate myoglobins or with hemoglobins, but is 35% homologous with human indoleamine dioxygenase (IDO), a vertebrate tryptophan-degrading enzyme. It does not share similar function with IDO. "The IDO-like myoglobin is unexpectedly widely distributed among gastropodic molluscs, such as Sulculus, Nordotis, Battilus, Omphalius and Chlorostoma."[237]

- The hemocyanin from arthropods and molluscs evolved from different ancestors, tyrosinase and insect storage proteins, respectively. They have different molecular weight and structure. However, the proteins both use copper binding sites to transport oxygen.[238]

- The hexokinase, ribokinase, and galactokinase families of sugar kinases have similar enzymatic functions of sugar phosphorylation, but they evolved from three distinct nonhomologous families since they all have distinct three-dimensional folding and their conserved sequence patterns are strikingly different.[239]

- Hemoglobins in jawed vertebrates and jawless fish evolved independently. The oxygen-binding hemoglobins of jawless fish evolved from an ancestor of cytoglobin which has no oxygen transport function and is expressed in fibroblast cells.[240]

- Toxic agent, serine protease BLTX, in the venom produced by two distinct species, the North American short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the Mexican beaded lizard, undergo convergent evolution. Although their structures are similar, it turns out that they increased the enzyme activity and toxicity through different way of structure changes. These changes are not found in the other non-venomous reptiles or mammals.[241]

- Another toxin BgK, a K+ channel-blocking toxin from the sea anemone Bunodosoma granulifera and scorpions adopt distinct scaffolds and unrelated structures, however, they have similar functions.[242]

- Antifreeze proteins are a perfect example of convergent evolution. Different small proteins with a flat surface which is rich in threonine from different organisms are selected to bind to the surface of ice crystals. "These include two proteins from fish, the ocean pout and the winter flounder, and three very active proteins from insects, the yellow mealworm beetle, the spruce budworm moth, and the snow flea."[243]

- RNA-binding proteins which contain RNA-binding domain (RBD) and the cold-shock domain (CSD) protein family are also an example of convergent evolution. Except that they both have conserved RNP motifs, other protein sequence are totally different. However, they have a similar function.[244]

- Blue-light-receptive cryptochrome expressed in the sponge eyes likely evolved convergently in the absence of opsins and nervous systems. The fully sequenced genome of Amphimedon queenslandica, a demosponge larvae, lacks one vital visual component: opsin-a gene for a light-sensitive opsin pigment which is essential for vision in other animals.[245]

- The structure of immunoglobulin G-binding bacterial proteins A and H do not contain any sequences homologous to the constant repeats of IgG antibodies, but they have similar functions. Both protein G, A, H are inhibited in the interactions with IgG antibodies (IgGFc) by a synthetic peptide corresponding to an 11-amino-acid-long sequence in the COOH-terminal region of the repeats.[246]

Structural convergence

Here is a list of examples in which unrelated proteins have similar tertiary structures but different functions. Whole protein structural convergence is not thought to occur but some convergence of pockets and secondary structural elements have been documented.

- Some secondary structure convergence occurs due to some residues favouring being in α-helix (helical propensity) and for hydrophobic patches or pocket to be formed at the ends of the parallel sheets.[247]

- ABAC is a database of convergently evolved protein interaction interfaces. Examples comprise fibronectin/long chain cytokines, NEF/SH2, cyclophilin/capsid proteins.[248]

See also

- McGhee, G.R. (2011) Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful. Vienna Series in Theoretical Biology: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press, Cambridge (MA). 322 pp.

Notes

- ^ Biomineralization is a process generally concomitant to biodegradation.[175]

References

- ^ L Werdelin (1986). "Comparison of Skull Shape in Marsupial and Placental Carnivores". Australian Journal of Zoology. 34 (2): 109–117. doi:10.1071/ZO9860109.

- ^ The phylogeny of the ungulates - Donald Prothero

- ^ Gheerbrant, Emmanuel; Filippo, Andrea; Schmitt, Arnaud (2016). "Convergence of Afrotherian and Laurasiatherian Ungulate-Like Mammals: First Morphological Evidence from the Paleocene of Morocco". PLOS ONE. 11 (7): e0157556. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1157556G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157556. PMC 4934866. PMID 27384169.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ tcnj.edu, ANTELOPE Vs. PRONGHORN

- ^ Luo, Zhe-Xi; Cifelli, Richard L.; Kielan-Jaworowska, Zofia (2001). "Dual origin of tribosphenic mammals". Nature. 409 (6816): 53–57. Bibcode:2001Natur.409...53L. doi:10.1038/35051023. PMID 11343108. S2CID 4342585.

- ^ The Curious Evolutionary History of the ‘Marsupial Wolf’ by Kyle Taitt

- ^ An Introduction to Zoology, Page 102, by Joseph Springer, Dennis Holley, 2012

- ^ Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful, page 158, by George R. McGhee, 2011

- ^ When Nature Discovers The Same Design Over and Over, By NATALIE ANGIER, Published: December 15, 1998

- ^ BBC, Koalas' Fingerprints

- ^ Convergent EVOLUTION: "Are Dolphins and Bats more related than we think?" by Cariosa Switzer, October 16, 2013

- ^ "Analogy: Squirrels and Sugar Gliders". Understanding Evolution. The University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ /jerboa.html desertusa.com, The Jerboa, by Jay Sharp

- ^ "johnabbott.qc.ca, Comparative Anatomy of Vertebrate Skeleta". Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare, page 137, D. S. Mills and Jeremy N. Marchant-Forde

- ^ weebly.com, Marsupials

- ^ "91st Annual Meeting, The American Society of Mammalogists, A Joint Meeting With The Australian Mammal Society Portland State University, 28 June 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ devilsatcradle.com, Tasmanian Devil - Sarcophilus harrisii Taxonomy

- ^ Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume 27, page 382, By Joel Asaph Allen

- ^ nationaldinosaurmuseum.com.au Thylacoleo Archived 2014-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yoon, Carol Kaesuk. "Donald R. Griffin, 88, Dies; Argued Animals Can Think", The New York Times, November 14, 2003. Accessed July 16, 2010.

- ^ D. R. Griffin (1958). Listening in the dark. Yale Univ. Press, New York.

- ^ a b Liu Y, Cotton JA, Shen B, Han X, Rossiter SJ, Zhang S (2010). "Convergent sequence evolution between echolocating bats and dolphins". Current Biology. 20 (2): R53–54. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.058. PMID 20129036. S2CID 16117978.

- ^ a b Liu, Y, Rossiter SJ, Han X, Cotton JA, Zhang S (2010). "Cetaceans on a molecular fast track to ultrasonic hearing". Current Biology. 20 (20): 1834–1839. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.008. PMID 20933423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Davies KT, Cotton JA, Kirwan J, Teeling EC, Rossiter SJ (2011). "Parallel signatures of sequence evolution among hearing genes in echolocating mammals: an emerging model of genetic convergence". Heredity. 108 (5): 480–489. doi:10.1038/hdy.2011.119. PMC 3330687. PMID 22167055.

- ^ Parker, J; Tsagkogeorga, G; Cotton, JA; Liu, Y; Provero, P; Stupka, E; Rossiter, SJ (2013). "Genome-wide signatures of convergent evolution in echolocating mammals". Nature. 502 (7470): 228–231. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..228P. doi:10.1038/nature12511. PMC 3836225. PMID 24005325.

- ^ Rawlins, D. R; Handasyde, K. A. (2002). "The feeding ecology of the striped possum Dactylopsila trivirgata (Marsupialia: Petauridae) in far north Queensland, Australia". J. Zool., Lond. (Zoological Society of London) 257: 195–206. 2010-04-09.

- ^ Ji, Q.; Luo, Z.-X.; Yuan, C.-X.; Tabrum, A. R. (2006). "A swimming mammaliaform from the Middle Jurassic and ecomorphological diversification of early mammals". Science. 311 (5764): 1123–1127. Bibcode:2006Sci...311.1123J. doi:10.1126/science.1123026. PMID 16497926. S2CID 46067702.

- ^ Organ, J. M. (2008). The Functional Anatomy of Prehensile and Nonprehensile Tails of the Platyrrhini (Primates) and Procyonidae (Carnivora). Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 9780549312260.

- ^ "Entelodont General Evidence". BBC Worldwide. 2002. Retrieved 2007-11-21.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (2005). The Ancestor's Tale. Boston: Mariner Books. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-618-61916-0.

- ^ whalefacts.org, Whale Shark Facts

- ^ "Duck-billed Platypus". Museum of hoaxes. Retrieved 2010-07-21.

- ^ "Platypus facts file". Australian Platypus Conservancy. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

- ^ "Avian Circulatory System". people.eku.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ The Behavior Guide to African Mammals: Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, By Richard Estes

- ^ Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, by William F. Perrin, Bernd Wursig, J. G.M. Thewissen

- ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2005/05/0519_050519_newmonkey_2.html nationalgeographic.com, New Monkey Species Discovered in East Africa, Genus Identification

- ^ planetearth.nerc.ac.uk, Copepods and whales share weight belt tactic, 16 June 2011, by Tom Marshall

- ^ a b theroamingnaturalist.com, Evolution Awesomeness Series #3: Convergent Evolution

- ^ edgeofexistence.org Fossa

- ^ a-z-animals.com Fossa

- ^ "Life in the Rainforest". Archived from the original on 2006-07-09. Retrieved 15 April 2006.

- ^ Corlett, Richard T.; Primack, Richard B. (2011). Tropical rain forests : an ecological and biogeographical comparison (2nd ed.). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 197, 200. ISBN 978-1444332551.

- ^ McKenna, M. C; S. K. Bell (1997). Classification of Mammals Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-11012-9.

- ^ American Museum of Natural History, "Perissodactyls Glossary"

- ^ Arrese, Catherine; 1 Nathan S. Hart; Nicole Thomas; Lyn D. Beazley; Julia Shand (16 April 2002). "Trichromacy in Australian Marsupials" (PDF). Current Biology. 12 (8): 657–660. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00772-8. PMID 11967153. S2CID 14604695. Archived from the original on February 20, 2005. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Rowe, Michael H (2002). "Trichromatic color vision in primates". News in Physiological Sciences. 17 (3): 93–98. doi:10.1152/nips.01376.2001. PMID 12021378.

- ^ "Rumination: The process of foregut fermentation". Archived from the original on 2013-07-19.

- ^ "Ruminant Digestive System" (PDF).

- ^ "metabolic water | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Klaassen M (1996). "Metabolic constraints on long-distance migration in birds". J Exp Biol. 199 (Pt 1): 57–64. PMID 9317335.

- ^ Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources (BANR), Nutrient Requirements of Nonhuman Primates: Second Revised Edition (2003), p. 144. [1]

- ^ Vorohuen (sic; Vorohué) Formation at Fossilworks.org

- ^ Witton, Mark (2013). Pterosaurs: Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy. Princeton University Press. p. 51.

- ^ Sereno, P.C. (1986). "Phylogeny of the bird-hipped dinosaurs (order Ornithischia)". National Geographic Research. 2 (2): 234–256.

- ^ Proctor, Nobel S. Manual of Ornithology: Avian Structure and Function. Yale University Press. (1993) ISBN 0-300-05746-6

- ^ David Lambert and the Diagram Group. The Field Guide to Prehistoric Life. New York: Facts on File Publications, 1985. pp. 196. ISBN 0-8160-1125-7

- ^ Bujor, Mara (2009-05-29). "Did sauropods walk with their necks upright?". ZME Science.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2011) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2010 Appendix.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (2009-06-29). "How dinosaurs chewed". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 2009-07-02. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- ^ Southampton, University of. "Fossil Saved from Mule Track Revolutionizes Understanding of Ancient Dolphin-Like Marine Reptile". Science Daily. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1890). "Additional characters of the Ceratopsidae, with notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 39 (233): 418–429. Bibcode:1890AmJS...39..418M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-39.233.418. S2CID 130812960.

- ^ Botha-Brink, J.; Modesto, S.P. (2007). "A mixed-age classed 'pelycosaur' aggregation from South Africa: earliest evidence of parental care in amniotes?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 274 (1627): 2829–2834. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0803. PMC 2288685. PMID 17848370.

- ^ Carroll, R.L. (1969). "Problems of the origin of reptiles". Biological Reviews. 44 (3): 393–432. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.1969.tb01218.x.

- ^ palaeos.com, Ornithischia: Hadrosauroidea

- ^ Agnolin, F.L.; Chiarelli, P. (2010). "The position of the claws in Noasauridae (Dinosauria: Abelisauroidea) and its implications for abelisauroid manus evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 84 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1007/s12542-009-0044-2. S2CID 84491924.

- ^ Zheng, Xiao-Ting; You, Hai-Lu; Xu, Xing; Dong, Zhi-Ming (2009). "An Early Cretaceous heterodontosaurid dinosaur with filamentous integumentary structures". Nature. 458 (7236): 333–336. Bibcode:2009Natur.458..333Z. doi:10.1038/nature07856. PMID 19295609. S2CID 4423110.

- ^ The Dinosauria: Second Edition, Page 193, David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson, Halszka Osmólska, 2004

- ^ Dixon, Dougal. "The Complete Book of Dinosaurs." Hermes House, 2006.

- ^ Holtz, Thomas R. Jr. (2012) Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix.

- ^ Larry D. Martin; Evgeny N. Kurochkin; Tim T. Tokaryk (2012). "A new evolutionary lineage of diving birds from the Late Cretaceous of North America and Asia". Palaeoworld. 21: 59–63. doi:10.1016/j.palwor.2012.02.005.

- ^ berkeley.edu, Phytosauria, The phytosaurs

- ^ Fischer, V.; A. Clement; M. Guiomar; P. Godefroit (2011). "The first definite record of a Valanginian ichthyosaur and its implications on the evolution of post-Liassic Ichthyosauria". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.11.005.

- ^ Hoser, R. (1998). "Death adders (genus Acanthophis): an overview, including descriptions of five new species and one subspecies". Monitor. 9 (2): 20–30, 33–41.

- ^ Ophisaurus at Life is Short, but Snakes are Long

- ^ Sheffield, K. Megan; Butcher, Michael T.; Shugart, S. Katharine; Gander, Jennifer C.; Blob, Richard W. (2011). "Locomotor loading mechanics in the hindlimbs of tegu lizards (Tupinambis merianae): Comparative and evolutionary implications". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (15): 2616–2630. doi:10.1242/jeb.048801. PMID 21753056.

- ^ Gamble T, Greenbaum E, Jackman TR, Russell AP, Bauer AM (2012). "Repeated origin and loss of adhesive toepads in geckos". PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e39429. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...739429G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039429. PMC 3384654. PMID 22761794.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Losos, Jonathan B. (2007). "Detective Work in the West Indies: Integrating Historical and Experimental Approaches to Study Island Lizard Evolution". BioScience. 57 (7): 585–97. doi:10.1641/B570712.

- ^ fox News, Deadliest sea snake splits in two, By Douglas Main, December 11, 2012

- ^ Christidis, Les; Boles, Walter (2008). Systematics and taxonomy of Australian Birds. Collingwood, Vic: CSIRO Publishing. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6

- ^ Christidis L, Boles WE (2008). Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds. Canberra: CSIRO Publishing. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-643-06511-6

- ^ The Origin and Evolution of Birds, Page 185, by Alan Feduccia, 1999

- ^ Vulture, By Thom van Dooren, page 20, 2011

- ^ Prinzinger, R.; Schafer T. & Schuchmann K. L. (1992). "Energy metabolism, respiratory quotient and breathing parameters in two convergent small bird species : the fork-tailed sunbird Aethopyga christinae (Nectariniidae) and the Chilean hummingbird Sephanoides sephanoides (Trochilidae)". Journal of thermal biology 17.

- ^ naturedocumentaries.org, Hawaiian Honeycreepers: Evolution in Hawaii

- ^ Harshman J, Braun EL, Braun MJ, et al. (September 2008). "Phylogenomic evidence for multiple losses of flight in ratite birds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (36): 13462–7. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513462H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803242105. PMC 2533212. PMID 18765814.

- ^ Holmes, Bob (2008-06-26). "Bird evolutionary tree given a shake by DNA study". New Scientist.

- ^ theguardian.com, Mystery bird: yellow-throated longclaw, Macronyx croceus, Dec. 2011

- ^ Cory, Charles B. (March 1918). "Catalogue of Birds of the Americas". Fieldiana Zoology. 197. 13 (Part 2): 13. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ beautyofbirds.com, Hairywoodpeckers, by Species account by Jeannine Miesle

- ^ Australian Birds by Donald Trounson, Molly Trounson, National Book Distributors and Publishers, 1996

- ^ University of North Carolina, Animal Bioacoustics: Communication and echolocation among aquatic and terrestrial animals

- ^ Evolution of brain structures for vocal learning in birds, by Erich D. JARVIS

- ^ Birn-Jeffery AV, Miller CE, Naish D, Rayfield EJ, Hone DW (2012). "Pedal claw curvature in birds, lizards and mesozoic dinosaurs--complicated categories and compensating for mass-specific and phylogenetic control". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e50555. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750555B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050555. PMC 3515613. PMID 23227184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walter, Timothy J.; Marar, Uma (2007). "Sleeping With One Eye Open" (PDF). Capitol Sleep Medicine Newsletter. pp. 3621–3628.

- ^ Payne, R. B. 1997. Avian brood parasitism. In D. H. Clayton and J. Moore (eds.), Host-parasite evolution: General principles and avian models, 338–369. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ Bale R, Neveln ID, Bhalla AP, MacIver MA, Patankar NA (April 2015). "Convergent evolution of mechanically optimal locomotion in aquatic invertebrates and vertebrates". PLOS Biology. 13 (4): e1002123. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002123. PMC 4412495. PMID 25919026.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Daeschler EB, Shubin NH, Jenkins FA (April 2006). "A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan". Nature. 440 (7085): 757–63. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. PMID 16598249.

- ^ mapoflife.org, Independent eye movement in fish, chameleons and frogmouths

- ^ .oscarfish.com, Cichlids and Sunfish: A Comparison, By Sandtiger

- ^ Kullander, Sven; Efrem Ferreira (2006). "A review of the South American cichlid genus Cichla, with descriptions of nine new species (Teleostei: Cichlidae)" (PDF). Ichthyological Explorations of Freshwaters. 17 (4).

- ^ Willis SC, Macrander J, Farias IP, Ortí G (2012). "Simultaneous delimitation of species and quantification of interspecific hybridization in Amazonian peacock cichlids (genus cichla) using multi-locus data". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 12 (1): 96. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-12-96. PMC 3563476. PMID 22727018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Crevel RW, Fedyk JK, Spurgeon MJ (July 2002). "Antifreeze proteins: characteristics, occurrence and human exposure". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 40 (7): 899–903. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(02)00042-X. PMID 12065210.

- ^ Chen L, DeVries AL, Cheng CH (April 1997). "Evolution of antifreeze glycoprotein gene from a trypsinogen gene in Antarctic notothenioid fish". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (8): 3811–6. Bibcode:1997PNAS...94.3811C. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.8.3811. PMC 20523. PMID 9108060.

- ^ Hopkins CD (December 1995). "Convergent designs for electrogenesis and electroreception". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 5 (6): 769–77. doi:10.1016/0959-4388(95)80105-7. PMID 8805421. S2CID 39794542.

- ^ Hopkins, C. D. (1995). "Convergent designs for electrogenesis and electroreception". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 5 (6): 769–777. doi:10.1016/0959-4388(95)80105-7. PMID 8805421. S2CID 39794542.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Family Gasterosteidae". FishBase. October 2012 version.

- ^ Fish, F. E. (1990). "Wing design and scaling of flying fish with regard to flight performance" (PDF). Journal of Zoology. 221 (3): 391–403. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb04009.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-20.

- ^ The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution by John A. Long

- ^ Cheney KL, Grutter AS, Blomberg SP, Marshall NJ (August 2009). "Blue and yellow signal cleaning behavior in coral reef fishes". Current Biology. 19 (15): 1283–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.028. PMID 19592250. S2CID 15354868.

- ^ Why are the eyes of larval Black Dragonfish on stalks? - Australian Museum

- ^ realmonstrosities.com, What's the Difference Between a Sawfish and a Sawshark? Sunday, 26 June 2011

- ^ Sewell, Aaron (March 2010). "Aquarium Fish: Physical Crypsis: Mimicry and Camouflage". Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ Aristotle. Historia Animalium. IX, 622a: 2-10. About 400 BC. Cited in Luciana Borrelli, Francesca Gherardi, Graziano Fiorito. A catalogue of body patterning in Cephalopoda. Firenze University Press, 2006. Abstract Google books

- ^ molluscs.at, Fresh Water Snails, Robert Nordsieck, Austria

- ^ mapoflife.org, Tongues of chameleons and amphibians

- ^ mongabay.com, Study discovers why poison dart frogs are toxic, by Rhett Butler, August 9, 2005

- ^ Nussbaum, Ronald A. (1998). Cogger, H.G. & Zweifel, R.G., ed. Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 52–59.

- ^ Niedźwiedzki (2010). "Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland". Nature. 463 (7277): 43–48. Bibcode:2010Natur.463...43N. doi:10.1038/nature08623. PMID 20054388. S2CID 4428903.

- ^ Hutchison, Victor (2008). "Amphibians: Lungs' Lift Lost". Current Biology. 18 (9): R392–R393. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.006. PMID 18460323.

- ^ Milner, Andrew R. (1980). "The Tetrapod Assemblage from Nýrany, Czechoslovakia". In Panchen, A. L. (ed.). The Terrestrial Environment and the Origin of Land Vertebrates. London and New York: Academic Press. pp. 439–96.

- ^ wired.com, Absurd Creature of the Week: Enormous Hermit Crab Tears Through Coconuts, Eats Kittens, By Matt Simon, 12.20.13

- ^ Herrera, Carlos M. (1992). "Activity pattern and thermal biology of a day-flying hawkmoth (Macroglossum stellatarum) under Mediterranean summer conditions". Ecological Entomology 17

- ^ "Defining Features of Nominal Clades of Diplopoda" (PDF). Field Museum of Natural History. Retrieved June 24, 2007.

- ^ Briones-Fourzán, Patricia; Lozano-Alvarez, Enrique (1991). "Aspects of the biology of the giant isopod Bathynomus giganteus A. Milne Edwards, 1879 (Flabellifera: Cirolanidae), off the Yucatan Peninsula". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 11 (3): 375–385. doi:10.2307/1548464. JSTOR 1548464.

- ^ Sutherland TD, Young JH, Weisman S, Hayashi CY, Merritt DJ (2010). "Insect silk: one name, many materials". Annual Review of Entomology. 55 (1): 171–88. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085401. PMID 19728833.

- ^ The Praying Mantids, Page 341, by Frederick R. Prete

- ^ Insects, pt. 1-4. History of the zoophytes. By Oliver Goldsmith, page 39

- ^ Fungal Biology, By J. W. Deacon, page 278

- ^ King, JR; Trager, JC.; Pérez-Lachaud, G. (2007), "Natural history of the slave making ant, Polyergus lucidus, sensu lato in northern Florida and its three Formica pallidefulva group hosts.", Journal of Insect Science, 7 (42): 1–14, doi:10.1673/031.007.4201, PMC 2999504, PMID 20345317

- ^ Goropashnaya, A. V.; Fedorov, V. B.; Seifert, B.; Pamilo, P. (2012), Chaline, Nicolas (ed.), "Phylogenetic Relationships of Palaearctic Formica Species (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) Based on Mitochondrial Cytochrome b Sequences", PLOS ONE, 7 (7): 1–7, Bibcode:2012PLoSO...741697G, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041697, PMC 3402446, PMID 22911845

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ D'Ettorre, Patrizia; Heinze, Jürgen (2001), "Sociobiology of slave-making ants", Acta Ethologica, 3 (2): 67–82, doi:10.1007/s102110100038, S2CID 37840769

- ^ Suzuki, Y.; Palopoli, M. (2001). "Evolution of insect abdominal appendages: Are prolegs homologous or convergent traits?". Development Genes and Evolution. 211 (10): 486–492. doi:10.1007/s00427-001-0182-3. PMID 11702198. S2CID 1163446.

- ^ Schmidt, O; Schuchmann-Feddersen, I (1989). "Role of virus-like particles in parasitoid-host interaction of insects". Subcell Biochem. Subcellular Biochemistry. 15: 91–119. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-1675-4_4. ISBN 978-1-4899-1677-8. PMID 2678620.

- ^ The Mysterious World, Top 10 shortest living animals in the world

- ^ University of Florida, Shortest Reproductive Life, Craig H. Welch, April 17, 1998 Archived July 30, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6 ed.). p. 1. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Dickinson, MH (29 May 1999). "Haltere-mediated equilibrium reflexes of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 354 (1385): 903–16. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0442. PMC 1692594. PMID 10382224.

- ^ Patsy A. McLaughlin; Rafael Lemaitre (1997). "Carcinization in the anomura – fact or fiction? I. Evidence from adult morphology". Contributions to Zoology. 67 (2): 79–123. doi:10.1163/18759866-06702001. PDF

- ^ maryland.gov, MOLLUSCS

- ^ University of Hawaii Archived 2006-06-03 at the Wayback Machine Educational page from Christopher F. Bird, Dep't of Botany. Photos and detailed information distinguishing the different varieties.

- ^ Lottia gigantea: taxonomy, facts, life cycle, bibliography

- ^ Yoshida, Masa-aki; Yura, Kei; Ogura, Atsushi (5 March 2014). "Cephalopod eye evolution was modulated by the acquisition of Pax-6 splicing variants". Scientific Reports. 4: 4256. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4256Y. doi:10.1038/srep04256. PMC 3942700. PMID 24594543.

- ^ Halder, G.; Callaerts, P.; Gehring, W. J. (1995). "New perspectives on eye evolution". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 5 (5): 602–609. doi:10.1016/0959-437X(95)80029-8. PMID 8664548.

- ^ "The illustration of the swim bladder in fishes is a good one, because it shows us clearly the highly important fact that an organ originally constructed for one purpose, namely, flotation, may be converted into one for a widely different purpose, namely, respiration. The swim bladder has, also, been worked in as an accessory to the auditory organs of certain fishes. All physiologists admit that the swimbladder is homologous, or "ideally similar" in position and structure with the lungs of the higher vertebrate animals: hence there is no reason to doubt that the swim bladder has actually been converted into lungs, or an organ used exclusively for respiration. According to this view it may be inferred that all vertebrate animals with true lungs are descended by ordinary generation from an ancient and unknown prototype, which was furnished with a floating apparatus or swim bladder." Darwin, Origin of Species.

- ^ fossilplot.org, Brachiopods and Bivalves: paired shells, with different histories

- ^ Mill, P. J.; Pickard, R. S. (1975). "Jet-propulsion in anisopteran dragonfly larvae". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 97 (4): 329–338. doi:10.1007/BF00631969. S2CID 45066664.

- ^ Bone, Q.; Trueman, E. R. (2009). "Jet propulsion of the calycophoran siphonophores Chelophyes and Abylopsis". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 62 (2): 263. doi:10.1017/S0025315400057271.

- ^ a b Bone, Q.; Trueman, E. R. (2009). "Jet propulsion in salps (Tunicata: Thaliacea)". Journal of Zoology. 201 (4): 481–506. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1983.tb05071.x.

- ^ Bone, Q.; Trueman, E. (1984). "Jet propulsion in Doliolum (Tunicata: Thaliacea)". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 76 (2): 105–118. doi:10.1016/0022-0981(84)90059-5.

- ^ Demont, M. Edwin; Gosline, John M. (January 1, 1988). "Mechanics of Jet Propulsion in the Hydromedusan Jellyfish (section I. Mechanical Properties of the Locomotor Structure)". J. Exp. Biol. 134 (134): 313–332.

- ^ Demont, M. Edwin; Gosline, John M. (January 1, 1988). "Mechanics of Jet Propulsion in the Hydromedusan Jellyfish (section II. Energetics of the Jet Cycle)". J. Exp. Biol. 134 (134): 333–345.

- ^ Demont, M. Edwin; Gosline, John M. (January 1, 1988). "Mechanics of Jet Propulsion in the Hydromedusan Jellyfish (section III. A Natural Resonating Bell; The Presence and Importance of a Resonant Phenomenon in the Locomotor Structure)". J. Exp. Biol. 134 (134): 347–361.

- ^ Madin, L. P. (1990). "Aspects of jet propulsion in salps". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 68 (4): 765–777. doi:10.1139/z90-111.

- ^ "faculty.vassar.edu, notochor" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ^ Benton, Michael J.; Harper, David A.T. (2009), Introduction to paleobiology and the fossil record, John Wiley & Sons, p. 77, ISBN 978-1-4051-8646-9

- ^ Smith WL, Wheeler WC (2006). "Venom evolution widespread in fishes: a phylogenetic road map for the bioprospecting of piscine venoms".

- ^ Meighen EA (1999). "Autoinduction of light emission in different species of bioluminescent bacteria". Luminescence. 14 (1): 3–9. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1522-7243(199901/02)14:1<3::AID-BIO507>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 10398554.

- ^ wn.com Bioluminescent

- ^ Liddell, Scott, Jones. γένεσις A.II, A Greek-English Lexicon, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940. q.v..

- ^ Robinson JL, Pyzyna B, Atrasz RG, et al. (February 2005). "Growth kinetics of extremely halophilic archaea (family halobacteriaceae) as revealed by arrhenius plots". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (3): 923–9. doi:10.1128/JB.187.3.923-929.2005. PMC 545725. PMID 15659670.

- ^ bio.sunyorange.edu, Gender and Sex Chromosomes

- ^ Strickberger's Evolution, By Brian Keith Hall, Page 188, Benedikt Hallgrímsson, Monroe W. Strickberger

- ^ sciencemag.org, Separate Evolutionary Origins of Teeth from Evidence in Fossil Jawed Vertebrates, by Moya Meredith Smith1 and Zerina Johanson, 21 February 2003

- ^ "Biology at the University of New Mexico, Vertebrate Adaptations". Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ^ birdsbybent.com, Ruby-throated HummingbirdArchilochus colubris

- ^ science.gov, Neuroglobins, Pivotal Proteins Associated with Emerging Neural Systems and Precursors of Metazoan Globin Diversity by Lechauve, Christophe; Jager, Muriel; Laguerre, Laurent; Kiger, Laurent; Correc, Gaelle; Leroux, Cedric; Vinogradov, Serge; Czjzek, Mirjam; Marden, Michael C.; Bail

- ^ Dunn, Casey (2005): Siphonophores. Retrieved 2008-JUL-08.

- ^ fox.rwu.edu Marine Ecology Progress Series, Dec. 7, 2006 By Sean P. Colin, John H. Costello, Heather Kordula

- ^ sciencedaily.com, Study sheds light on tunicate evolution, July 5, 2011, Source: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- ^ Crespi B. J. (1992). "Eusociality in Australian gall thrips". Nature. 359 (6397): 724–726. Bibcode:1992Natur.359..724C. doi:10.1038/359724a0. S2CID 4242926.

- ^ Science Coop, The Difference between Hemocyanin and Hemoglobin

- ^ a b Vert, Michel (2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04. S2CID 98107080.

- ^ Klappa, Colin F. (1979). "Lichen Stromatolites: Criterion for Subaerial Exposure and a Mechanism for the Formation of Laminar Calcretes (Caliche)". Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. 49 (2): 387–400. doi:10.1306/212F7752-2B24-11D7-8648000102C1865D.

- ^ Paleobotany: The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants, Edith L. Taylor, Thomas N. Taylor, Michael Krings, page [2]

- ^ Maloof, A.C. (2010). "Constraints on early Cambrian carbon cycling from the duration of the Nemakit-Daldynian–Tommotian boundary, Morocco". Geology. 38 (7): 623–626. Bibcode:2010Geo....38..623M. doi:10.1130/G30726.1. S2CID 128842533.

- ^ University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, The Magnetic Sense of Animals

- ^ Sea sky, Giant Tube Worm (Riftia pachyptila)

- ^ "What is a lichen?, Australian National Botanical Garden". Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Introduction to Lichens - An Alliance between Kingdoms, University of California Museum charity's Williams of Paleontology, [3]

- ^ Margulis, Lynn; Barreno, Eva (2003). "Looking at Lichens". BioScience. 53 (8): 776–778. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0776:LAL]2.0.CO;2.