Book of Genesis

| |||||

| Tanakh (Judaism) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Old Testament (Christianity) | |||||

|

|

|||||

| Bible portal | |||||

The Book of Genesis,[a] the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament,[1] is an account of the creation of the world, the early history of humanity, Israel's ancestors and the origins of the Jewish people.[2] Its Hebrew name is the same as its first word, Bereshit ("In the beginning").

It is divisible into two parts, the primeval history (chapters 1–11) and the ancestral history (chapters 12–50).[3] The primeval history sets out the author's concepts of the nature of the deity and of humankind's relationship with its maker: God creates a world which is good and fit for mankind, but when man corrupts it with sin God decides to destroy his creation, saving only the righteous Noah to reestablish the relationship between man and God.[4] The ancestral history (chapters 12–50) tells of the prehistory of Israel, God's chosen people.[5] At God's command Noah's descendant Abraham journeys from his birthplace (described as Ur of the Chaldeans and whose identification with Sumerian Ur is tentative in modern scholarship) into the God-given land of Canaan, where he dwells as a sojourner, as does his son Isaac and his grandson Jacob. Jacob's name is changed to Israel, and through the agency of his son Joseph, the children of Israel descend into Egypt, 70 people in all with their households, and God promises them a future of greatness. Genesis ends with Israel in Egypt, ready for the coming of Moses and the Exodus. The narrative is punctuated by a series of covenants with God, successively narrowing in scope from all mankind (the covenant with Noah) to a special relationship with one people alone (Abraham and his descendants through Isaac and Jacob).[6]

In Judaism, the theological importance of Genesis centers on the covenants linking God to his chosen people and the people to the Promised Land. Christianity has interpreted Genesis as the prefiguration of certain cardinal Christian beliefs, primarily the need for salvation (the hope or assurance of all Christians) and the redemptive act of Christ on the Cross as the fulfillment of covenant promises as the Son of God.

Tradition credits Moses as the author of Genesis, as well as the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and most of Deuteronomy, but modern scholars especially from the 19th century onward see them as a product of the 6th and 5th centuries BC.[7][8]

Structure

Genesis appears to be structured around the recurring phrase elleh toledot, meaning "these are the generations," with the first use of the phrase referring to the "generations of heaven and earth" and the remainder marking individuals—Noah, the "sons of Noah", Shem, etc., down to Jacob.[9] It is not clear, however, what this meant to the original authors, and most modern commentators divide it into two parts based on subject matter, a "primeval history" (chapters 1–11) and a "patriarchal history" (chapters 12–50).[10][b] While the first is far shorter than the second, it sets out the basic themes and provides an interpretive key for understanding the entire book.[11] The "primeval history" has a symmetrical structure hinging on chapters 6–9, the flood story, with the events before the flood mirrored by the events after;[12] the "ancestral history" is structured around the three patriarchs Abraham, Jacob and Joseph.[13] (The stories of Isaac do not make up a coherent cycle of stories and function as a bridge between the cycles of Abraham and Jacob.)[14]

The toledot formula, occurring eleven times in the book of Genesis, delineating its sections and shaping its structure, serves as a heading which marks a transition to a new subject:

- Genesis 1:1 (narrative) In the beginning

- Genesis 2:4 (narrative) Toledot of Heaven and Earth

- Genesis 5:1 (genealogy) Toledot of Adam

- Genesis 6:9 (narrative) Toledot of Noah

- Genesis 10:1 (genealogy) Toledot of Shem, Ham, and Japheth

- Genesis 11:1 (narrative without toledot) The tower of Babel

- Genesis 11:10 (genealogy) Toledot of Shem

- Genesis 11:27 (narrative) Toledot of Terach

- Genesis 25:12 (genealogy) Toledot of Ishmael

- Genesis 25:19 (narrative) Toledot of Isaac

- Genesis 36:1 & 36:9 (genealogy) Toledot of Esau

- Genesis 37:2 (narrative) Toledot of Jacob[15][16]

Summary

There are two distinct versions of God's creation of the world in Genesis.[17]God creates the world in six days and consecrates the seventh as a day of rest. God creates the first humans Adam and Eve and all the animals in the Garden of Eden but instructs them not to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. A talking serpent portrayed as a deceptive creature or trickster, entices Eve into eating it against God's wishes, and she entices Adam, whereupon God throws them out and curses them—Adam to getting what he needs only by sweat and work, and Eve to giving birth in pain. This is interpreted by Christians as the fall of humanity. Eve bears two sons, Cain and Abel. Cain kills Abel after God accepts Abel's offering but not Cain's. God then curses Cain. Eve bears another son, Seth, to take Abel's place.

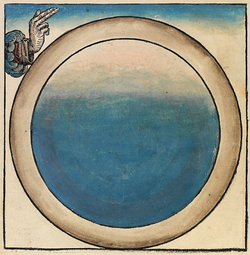

After many generations of Adam have passed from the lines of Cain and Seth, the world becomes corrupted by human sin and Nephilim, and God determines to wipe out humanity. First, he instructs the righteous Noah and his family to build an ark and put examples of all the animals on it, seven pairs of every clean animal and one pair of every unclean. Then God sends a great flood to wipe out the rest of the world. When the waters recede, God promises he will never destroy the world with water again, using the rainbow as a symbol of his promise. God sees mankind cooperating to build a great tower city, the Tower of Babel, and divides humanity with many languages and sets them apart with confusion.

God instructs Abram to travel from his home in Mesopotamia to the land of Canaan. There, God makes a covenant with Abram, promising that his descendants shall be as numerous as the stars, but that people will suffer oppression in a foreign land for four hundred years, after which they will inherit the land "from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates". Abram's name is changed to Abraham and that of his wife Sarai to Sarah, and circumcision of all males is instituted as the sign of the covenant. Due to her old age, Sarah tells Abraham to take her Egyptian handmaiden, Hagar, as a second wife. Through Hagar, Abraham fathers Ishmael.

God resolves to destroy the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah for the sins of their people. Abraham protests and gets God to agree not to destroy the cities for the sake of ten righteous men. Angels save Abraham's nephew Lot and his family, but his wife looks back on the destruction against their command and turns into a pillar of salt. Lot's daughters, concerned that they are fugitives who will never find husbands, get him drunk to become pregnant by him, and give birth to the ancestors of the Moabites and Ammonites.

Abraham and Sarah go to the Philistine town of Gerar, pretending to be brother and sister (they are half-siblings). The King of Gerar takes Sarah for his wife, but God warns him to return her, and he obeys. God sends Sarah a son whom she will name Isaac; through him will be the establishment of the covenant. Sarah drives Ishmael and his mother Hagar out into the wilderness, but God saves them and promises to make Ishmael a great nation.

God tests Abraham by demanding that he sacrifice Isaac. As Abraham is about to lay the knife upon his son, God restrains him, promising him numberless descendants. On the death of Sarah, Abraham purchases Machpelah (believed to be modern Hebron) for a family tomb and sends his servant to Mesopotamia to find among his relations a wife for Isaac; after proving herself, Rebekah becomes Isaac's betrothed. Keturah, Abraham's other wife, births more children, among whose descendants are the Midianites. Abraham dies at a prosperous old age and his family lays him to rest in Hebron.

Isaac's wife Rebecca gives birth to the twins Esau, father of the Edomites, and Jacob. Through deception, Jacob becomes the heir instead of Esau and gains his father's blessing. He flees to his uncle where he prospers and earns his two wives, Rachel and Leah. Jacob's name is changed to Israel, and by his wives and their handmaidens he has twelve sons, the ancestors of the twelve tribes of the Children of Israel, and a daughter, Dinah.

Joseph, Jacob's favorite son, makes his brothers jealous and they sell him into slavery in Egypt. Joseph prospers, after hardship, with God's guidance of interpreting Pharaoh's dream of upcoming famine. He is then reunited with his father and brothers, who fail to recognize him, and plead for food. After much manipulation, he reveals himself and lets them and their households into Egypt, where Pharaoh assigns to them the land of Goshen. Jacob calls his sons to his bedside and reveals their future before he dies. Joseph lives to an old age and exhorts his brethren, if God should lead them out of the country, to take his bones with them.

Composition

Title and textual witnesses

Genesis takes its Hebrew title from the first word of the first sentence, Bereshit, meaning "In [the] beginning [of]"; in the Greek Septuagint it was called Genesis, from the phrase "the generations of heaven and earth".[18] There are four major textual witnesses to the book: the Masoretic Text, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Septuagint, and fragments of Genesis found at Qumran. The Qumran group provides the oldest manuscripts but covers only a small proportion of the book; in general, the Masoretic Text is well preserved and reliable, but there are many individual instances where the other versions preserve a superior reading.[19]

Origins

For much of the 20th century most scholars agreed that the five books of the Pentateuch—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy—came from four sources, the Yahwist, the Elohist, the Deuteronomist and the Priestly source, each telling the same basic story, and joined together by various editors.[20] Since the 1970s there has been a revolution leading scholars to view the Elohist source as no more than a variation on the Yahwist, and the Priestly source as a body of revisions and expansions to the Yahwist (or "non-Priestly") material. (The Deuteronomistic source does not appear in Genesis.)[21]

Scholars use examples of repeated and duplicate stories to identify the separate sources. In Genesis these include three different accounts of a Patriarch claiming that his wife was his sister, the two creation stories, and the two versions of Abraham sending Hagar and Ishmael into the desert.[22]

This leaves the question of when these works were created. Scholars in the first half of the 20th century came to the conclusion that the Yahwist is a product of the monarchic period, specifically at the court of Solomon, 10th century BC, and the Priestly work in the middle of the 5th century BC (with claims that the author is Ezra), but more recent thinking is that the Yahwist is from either just before or during the Babylonian exile of the 6th century BC, and the Priestly final edition was made late in the Exilic period or soon after.[8]

As for why the book was created, a theory which has gained considerable interest, although still controversial is "Persian imperial authorisation". This proposes that the Persians of the Achaemenid Empire, after their conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, agreed to grant Jerusalem a large measure of local autonomy within the empire, but required the local authorities to produce a single law code accepted by the entire community. The two powerful groups making up the community—the priestly families who controlled the Temple and who traced their origin to Moses and the wilderness wanderings, and the major landowning families who made up the "elders" and who traced their own origins to Abraham, who had "given" them the land—were in conflict over many issues, and each had its own "history of origins", but the Persian promise of greatly increased local autonomy for all provided a powerful incentive to cooperate in producing a single text.[23]

Genre

Genesis is an example of a creation myth, a type of literature telling of the first appearance of humans, the stories of ancestors and heroes, and the origins of culture, cities and so forth.[24] The most notable examples are found in the work of Greek historians of the 6th century BC: their intention was to connect notable families of their own day to a distant and heroic past, and in doing so they did not distinguish between myth, legend, and facts.[25] Professor Jean-Louis Ska of the Pontifical Biblical Institute calls the basic rule of the antiquarian historian the "law of conservation": everything old is valuable, nothing is eliminated.[26] Ska also points out the purpose behind such antiquarian histories: antiquity is needed to prove the worth of Israel's traditions to the nations (the neighbours of the Jews in early Persian Palestine), and to reconcile and unite the various factions within Israel itself.[26]

Themes

Promises to the ancestors

In 1978 David Clines published his influential The Theme of the Pentateuch – influential because he was one of the first to take up the question of the theme of the entire five books. Clines' conclusion was that the overall theme is "the partial fulfillment – which implies also the partial nonfulfillment – of the promise to or blessing of the Patriarchs". (By calling the fulfillment "partial" Clines was drawing attention to the fact that at the end of Deuteronomy the people are still outside Canaan).[27]

The patriarchs, or ancestors, are Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, with their wives (Joseph is normally excluded).[28] Since the name YHWH had not been revealed to them, they worshipped El in his various manifestations.[29] (It is, however, worth noting that in the Jahwist source the patriarchs refer to deity by the name YHWH, for example in Genesis 15.) Through the patriarchs God announces the election of Israel, meaning that he has chosen Israel to be his special people and committed himself to their future.[30] God tells the patriarchs that he will be faithful to their descendants (i.e. to Israel), and Israel is expected to have faith in God and his promise. ("Faith" in the context of Genesis and the Hebrew Bible means agreement to the promissory relationship, not a body of belief).[31]

The promise itself has three parts: offspring, blessings, and land.[32] The fulfilment of the promise to each patriarch depends on having a male heir, and the story is constantly complicated by the fact that each prospective mother – Sarah, Rebekah and Rachel – is barren. The ancestors, however, retain their faith in God and God in each case gives a son – in Jacob's case, twelve sons, the foundation of the chosen Israelites. Each succeeding generation of the three promises attains a more rich fulfillment, until through Joseph "all the world" attains salvation from famine,[33] and by bringing the children of Israel down to Egypt he becomes the means through which the promise can be fulfilled.[28]

God's chosen people

Scholars generally agree that the theme of divine promise unites the patriarchal cycles, but many would dispute the efficacy of trying to examine Genesis' theology by pursuing a single overarching theme, instead citing as more productive the analysis of the Abraham cycle, the Jacob cycle, and the Joseph cycle, and the Yahwist and Priestly sources.[34] The problem lies in finding a way to unite the patriarchal theme of divine promise to the stories of Genesis 1–11 (the primeval history) with their theme of God's forgiveness in the face of man's evil nature.[35][36] One solution is to see the patriarchal stories as resulting from God's decision not to remain alienated from mankind:[36] God creates the world and mankind, mankind rebels, and God "elects" (chooses) Abraham.[6]

To this basic plot (which comes from the Yahwist) the Priestly source has added a series of covenants dividing history into stages, each with its own distinctive "sign". The first covenant is between God and all living creatures, and is marked by the sign of the rainbow; the second is with the descendants of Abraham (Ishmaelites and others as well as Israelites), and its sign is circumcision; and the last, which does not appear until the book of Exodus, is with Israel alone, and its sign is Sabbath. A great leader mediates each covenant (Noah, Abraham, Moses), and at each stage God progressively reveals himself by his name (Elohim with Noah, El Shaddai with Abraham, Yahweh with Moses).[6]

Judaism's weekly Torah portions in the Book of Genesis

- Bereshit, on Genesis 1–6: Creation, Eden, Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, Lamech, wickedness

- Noach, on Genesis 6–11: Noah's Ark, the Flood, Noah's drunkenness, the Tower of Babel

- Lech-Lecha, on Genesis 12–17: Abraham, Sarah, Lot, covenant, Hagar and Ishmael, circumcision

- Vayeira, on Genesis 18–22: Abraham's visitors, Sodomites, Lot's visitors and flight, Hagar expelled, binding of Isaac

- Chayei Sarah, on Genesis 23–25: Sarah buried, Rebekah for Isaac

- Toledot, on Genesis 25–28: Esau and Jacob, Esau's birthright, Isaac's blessing

- Vayetze, on Genesis 28–32: Jacob flees, Rachel, Leah, Laban, Jacob's children and departure

- Vayishlach, on Genesis 32–36: Jacob's reunion with Esau, the rape of Dinah

- Vayeshev, on Genesis 37–40: Joseph's dreams, coat, and slavery, Judah with Tamar, Joseph and Potiphar

- Miketz, on Genesis 41–44: Pharaoh's dream, Joseph in government, Joseph's brothers visit Egypt

- Vayigash, on Genesis 44–47: Joseph reveals himself, Jacob moves to Egypt

- Vaychi, on Genesis 47–50: Jacob's blessings, death of Jacob and of Joseph

See also

- Dating the Bible

- Enûma Eliš

- Genesis creation narrative

- Genesis 1:1

- Historicity of the Bible

- Mosaic authorship

- Paradise Lost

- Protevangelium

- Wife–sister narratives in the Book of Genesis

Notes

- ^ The name "Genesis" is from the Latin Vulgate, in turn borrowed or transliterated from Greek "γένεσις", meaning "Origin"; Template:Lang-he-n, "Bərēšīṯ", "In [the] beginning"

- ^ The Weekly Torah portions, Parashot, divide the book into 12 readings.

References

- ^ Hamilton 1990, p. 1.

- ^ Sweeney 2012, p. 657.

- ^ Bergant 2013, p. xii.

- ^ Bandstra 2008, p. 35.

- ^ Bandstra 2008, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Bandstra (2004), pp. 28–29

- ^ Van Seters (1998), p. 5

- ^ a b Davies (1998), p. 37

- ^ Hamilton (1990), p. 2

- ^ Whybray (1997), p. 41

- ^ McKeown (2008), p. 2

- ^ Walsh (2001), p. 112

- ^ Bergant 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Bergant 2013, p. 103.

- ^ Schwartz (2016), p.1

- ^ Leithart (2017)

- ^ Joel S. Baden,The Book of Exodus: A Biography, Princeton University Press 2019 ISBN 978-0-691-18927-7 p.14. Speaking of the disunity of the Pentateuch, Baden writes:' Two creation stories of Genesis 1 and 2 provide the opening salvo. It is impossible to read them as a single unified narrative, as they disagree on almost every point, from the nature of the precreation world to the order of creation to the length of time creation took.'

- ^ Carr 2000, p. 491.

- ^ Hendel, R. S. (1992). "Genesis, Book of". In D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 2, p. 933). New York: Doubleday

- ^ Gooder (2000), pp. 12–14

- ^ Van Seters (2004), pp. 30–86

- ^ Lawrence Boadt; Richard J. Clifford; Daniel J. Harrington (2012). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction. Paulist Press.

- ^ Ska (2006), pp. 169, 217–18

- ^ Van Seters (2004) pp. 113–14

- ^ Whybray (2001), p. 39

- ^ a b Ska (2006), p. 169

- ^ Clines (1997), p. 30

- ^ a b Hamilton (1990), p. 50

- ^ John J Collins (2007), A Short Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, Fortress Press, p. 47

- ^ Brueggemann (2002), p. 61

- ^ Brueggemann (2002), p. 78

- ^ McKeown (2008), p. 4

- ^ Wenham (2003), p. 34

- ^ Hamilton (1990), pp. 38–39

- ^ Hendel, R. S. (1992). "Genesis, Book of". In D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 2, p. 935). New York: Doubleday

- ^ a b Kugler, Hartin (2009), p.9

Bibliography

Commentaries on Genesis

- Sweeney, Marvin (2012). "Genesis in the Context of Jewish Thought". In Evans, Craig A.; Lohr, Joel N. (eds.). The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004226531.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0495391050.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bergant, Dianne (2013). Genesis: In the Beginning. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814682753.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567372871.

- Brueggemann, Walter (1986). Genesis. Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Atlanta: John Knox Press. ISBN 0-8042-3101-X.

- Carr, David M. (2000). "Genesis, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9780567372871.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cotter, David W (2003). Genesis. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650400.

- De La Torre, Miguel (2011). Genesis. Belief: A Theological Commentary on the Bible. Westminster John Knox Press.

- Fretheim, Terence E. "The Book of Genesis." In The New Interpreter's Bible. Edited by Leander E. Keck, vol. 1, pp. 319–674. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994. ISBN 0-687-27814-7.

- Hamilton, Victor P (1990). The Book of Genesis: chapters 1–17. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825216.

- Hamilton, Victor P (1995). The Book of Genesis: chapters 18–50. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823090.

- Hirsch, Samson Raphael. The Pentateuch: Genesis. Translated by Isaac Levy. Judaica Press, 2nd edition 1999. ISBN 0-910818-12-6. Originally published as Der Pentateuch uebersetzt und erklaert Frankfurt, 1867–1878.

- Kass, Leon R. The Beginning of Wisdom: Reading Genesis. New York: Free Press, 2003. ISBN 0-7432-4299-8.

- Kessler, Martin; Deurloo, Karel Adriaan (2004). A Commentary on Genesis: The Book of Beginnings. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809142057.

- McKeown, James (2008). Genesis. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802827050.

- Plaut, Gunther. The Torah: A Modern Commentary (1981), ISBN 0-8074-0055-6

- Rogerson, John William (1991). Genesis 1–11. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567083388.

- Sacks, Robert D (1990). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis. Edwin Mellen.

- Sarna, Nahum M. The JPS Torah Commentary: Genesis: The Traditional Hebrew Text with the New JPS Translation. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1989. ISBN 0-8276-0326-6.

- Speiser, E.A. Genesis: Introduction, Translation, and Notes. New York: Anchor Bible, 1964. ISBN 0-385-00854-6.

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Turner, Laurence (2009). Genesis, Second Edition. Sheffield Phoenix Press. ISBN 9781906055653.

- Von Rad, Gerhard (1972). Genesis: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227456.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). "Genesis". In James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson (ed.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Whybray, R.N (2001). "Genesis". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

General

- Bandstra, Barry L (2004). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495391050.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2004). Treasures old and new: Essays in the Theology of the Pentateuch. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802826794.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of faith: A Theological Handbook of Old Testament themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664222314.

- Campbell, Antony F; O'Brien, Mark A (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

- Carr, David M (1996). Reading the Fractures of Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220716.

- Clines, David A (1997). The Theme of the Pentateuch. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567431967.

- Davies, G.I (1998). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Gooder, Paula (2000). The Pentateuch: A Story of Beginnings. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567084187.

- Hendel, Ronald (2012). The Book of "Genesis": A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691140124.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). The Old Testament between Theology and History: A Critical Survey. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Levin, Christoph L (2005). The Old Testament: A Brief Introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691113944.

- Longman, Tremper (2005). How to read Genesis. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830875603.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- Newman, Murray L. (1999). Genesis (PDF). Forward Movement Publications, Cincinnati, OH.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to Reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Van Seters, John (1992). Prologue to History: The Yahwist as Historian in Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664221799.

- Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham (ed.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: A Social-science Commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567080882.

- Walsh, Jerome T (2001). Style and Structure in Biblical Hebrew Narrative. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658970.

External links

- Book of Genesis Hebrew Transliteration

- Book of Genesis illustrated

- Genesis Reading Room (Tyndale Seminary): online commentaries and monographs on Genesis.

- Bereshit with commentary in Hebrew

- בראשית Bereishit – Genesis (Hebrew – English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Genesis at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society translation)

01 Genesis public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions

01 Genesis public domain audiobook at LibriVox Various versions- Genesis (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Genesis (Judaica Press) at Chabad.org

- Young's Literal Translation (YLT)

- New International Version (NIV)

- Revised Standard Version (RSV)

- Westminster-Leningrad codex

- Aleppo Codex

- Book of Genesis in Bible Book

- Genesis in Hebrew, Aramaic, Syriac, Greek, Latin, and English – The critical text of the Book of Genesis in Hebrew with ancient versions (Masoretic, Samaritan Pentateuch, Samaritan Targum, Targum Onkelos, Peshitta, Septuagint, Vetus Latina, Vulgate, Aquila, Symmachus, and Theodotion) and English translation for each version in parallel.