Blowup

| Blow-up | |

|---|---|

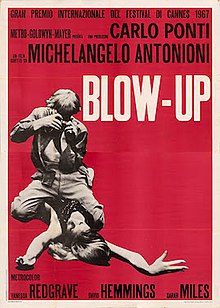

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Dialogue by | Edward Bond |

| Story by | Michelangelo Antonioni |

| Based on | Las babas del diablo by Julio Cortázar |

| Produced by | Carlo Ponti |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Carlo Di Palma |

| Edited by | Frank Clarke |

| Music by | Herbert Hancock |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Premier Productions |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.8 million[2] |

| Box office | $20 million[2] |

Blowup (sometimes styled as Blow-up or Blow Up) is a 1966 mystery thriller film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and produced by Carlo Ponti. It was Antonioni's first entirely English-language film, and stars David Hemmings as a London fashion photographer who believes he has unwittingly captured a murder on film. The film also stars Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles, John Castle, Jane Birkin, Tsai Chin, Peter Bowles, and Gillian Hills, as well as 1960s model Veruschka.

The film's plot was inspired by Julio Cortázar's short story "Las babas del diablo" (1959).[3] The screenplay was by Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, with English dialogue by British playwright Edward Bond.[4] The cinematographer was Carlo di Palma. The film's non-diegetic music was scored by jazz pianist Herbie Hancock, while rock group the Yardbirds also feature. The film is set within the mod subculture of 1960s Swinging London.[5]

In the main competition section of the Cannes Film Festival, Blowup won the Grand Prix du Festival International du Film, the festival's highest honour. The American release of the counterculture-era[6] film with its explicit sexual content was in direct defiance of Hollywood's Production Code. Its subsequent critical and box-office success influenced the abandonment of the code in 1968 in favour of the MPAA film rating system.[7]

Blowup would inspire subsequent films, including Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974) and Brian De Palma's Blow Out (1981).[8] In 2012, Blowup was ranked No. 144 in the Sight & Sound critics' poll of the world's greatest films.[9]

Plot

The narrative covers a day in the life of a glamorous fashion photographer, Thomas (Hemmings), the character's creation being inspired by the life of an actual "Swinging London" photographer, David Bailey,[10] and contemporaries such as Terence Donovan, David Montgomery and John Cowan.

After spending the night at a doss house, where he has taken pictures for a book of art photos, Thomas is late for a photo shoot with Veruschka at his studio, which in turn makes him late for a shoot with other models later in the morning. He grows bored and walks off, leaving the models and production staff in the lurch. As he leaves the studio, two teenaged girls who are aspiring models (Birkin and Hills) ask to speak with him, but the photographer drives off to look at an antique shop.

Wandering into Maryon Park, he takes photos of two lovers. The woman (Vanessa Redgrave) is furious at being photographed, pursues Thomas, demands his film, and ultimately tries to snatch his camera. He refuses and photographs her as she runs off.

Thomas then meets his agent Ron (Peter Bowles) for lunch, and notices a man following him and looking into his car. Back at his studio, the woman from the park arrives, asking desperately for the film. They have a conversation and flirt, but he deliberately hands her a different film roll. She, in turn, writes down a false telephone number and gives it to him.

He, curious, makes many enlargements of the black-and-white film of the two lovers. They reveal the woman worriedly looking at a third person lurking in the trees with a pistol. Thomas excitedly calls Ron, claiming his impromptu photo session may have saved a man's life. Thomas is disturbed by a knock on the door, and it is the two girls again, with whom he has a romp in his studio and falls asleep. Awakening, he finds they hope he will photograph them, but he realizes there may be more to the photographs in the park. He tells them to leave, saying, "Tomorrow! Tomorrow!"

Further examination of a blurred figure under a bush makes Thomas suspect the man in the park may have been murdered after all, during the time Thomas was arguing with the woman around the bend.

As evening falls, the photographer goes back to the park and finds the body of the man, but he has not brought his camera and is scared off by the sound of a twig breaking, as if being stepped on. Thomas returns to find his studio ransacked. All the negatives and prints are gone except for one very grainy blowup of what is possibly the body.

After driving into town, he sees the woman and follows her into a club where The Yardbirds, featuring both Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck on guitar and Keith Relf on vocals, are seen performing the song "Stroll On". A buzz in Beck's amplifier angers him so much, he smashes his guitar on stage, then throws its neck into the crowd. A riot ensues. The photographer grabs the neck and runs out of the club before anyone can snatch it from him. Then, he has second thoughts about it, throws it on the pavement, and walks away. A passer-by picks up the neck and throws it back down, not realizing it is from Beck's guitar.[11] Thomas never locates the elusive woman.

At a drug-drenched party in a house on the Thames near central London, the photographer finds Veruschka, who had told him that she was going to Paris; when confronted, she says she is in Paris. Thomas asks Ron to come to the park as a witness, but cannot convince him of what has happened because Ron is incredibly stoned. Instead, Thomas joins the party and wakes up in the house at sunrise. He returns to the park alone, only to find that the body is gone.

Befuddled, Thomas watches a mimed tennis match, is drawn into it, and picks up the imaginary ball and throws it back to the two players. While he watches the mime, the sound of the ball being played is heard and his image fades away, leaving only the grass as the film ends.

Cast

- David Hemmings as Thomas

- Vanessa Redgrave as Jane

- Sarah Miles as Patricia

- John Castle as Bill

- Jane Birkin as the Blonde

- Gillian Hills as the Brunette

- Peter Bowles as Ron

- Veruschka von Lehndorff as herself

- Julian Chagrin as Mime

- Claude Chagrin as Mime

- Susan Brodrick as Antique Shop Owner (uncredited)

- Tsai Chin as Thomas's receptionist (uncredited)

- Jill Kennington as Model (uncredited)

- Peggy Moffitt as Model (uncredited)

- Harry Hutchinson as Shopkeeper (uncredited)

- Ronan O'Casey as Jane's lover in the park (uncredited)

- Reg Wilkins as Thomas's Assistant (uncredited)

Production

The plot of Blowup was inspired by Julio Cortázar's short story "Las babas del diablo" (1959),[3] collected in the book End of the Game and Other Stories, in turn based on a story told to Cortázar by photographer Sergio Larraín.[12] Subsequently, the short story was retitled "Blow Up" to connect it with the film.[3] The life of Swinging London photographer David Bailey was also an influence.[13]

Several people were offered the role of the protagonist, including Sean Connery, who declined when Antonioni refused to show him the script, the photographer David Bailey, and Terence Stamp, who was replaced shortly before filming began after Antonioni found David Hemmings in a stage production of Dylan Thomas’s Adventures in the Skin Trade.[14]

The opening mimes were filmed on the Plaza of The Economist Building in St. James's Street, London, a project by 'New Brutalists' Alison and Peter Smithson constructed between 1959–64.[15] The park scenes were at Maryon Park, Charlton, south-east London, and the park has changed little since the film.[16] Photographer Jon Cowan leased his studio at 39 Princes Place to Antonioni for much of the interior and exterior filming, and Cowan's own photographic murals are featured in the film.[17][18] Other locations included Heddon Street[19] where the album cover of David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust was later photographed,[20] and Cheyne Walk, in Chelsea.

The rock club scene featuring the Yardbirds performing "Stroll On" – a modified version of "Train Kept A-Rollin'" – was filmed at Elstree Studios, from 12 to 14 October 1966.[21]

Actor Ronan O'Casey (dated 10 February 1999) claimed that the film's mysterious nature is the product of an "unfinished" production, and that scenes which would have "depict[ed] the planning of the murder and its aftermath – scenes with Vanessa, Sarah Miles and Jeremy Glover, Vanessa's new young lover who plots with her to murder me – were never shot because the film went seriously over budget."[22] Two scenes in particular give credence to this theory: the first in the restaurant when Glover's character is seen apparently tampering with Thomas' car, and the second when Glover and Redgrave are glimpsed together in a Rover 2000 (which also appears elsewhere) following Thomas' Rolls Royce.

Release

MGM did not gain approval for the film under the MPAA Production Code in the United States.[5] The film was condemned by the National Legion of Decency. The code's collapse and revision was foreshadowed when MGM released the film through a subsidiary distributor, Premier Productions, and Blowup was shown widely in North American cinemas.[7]

Writing about Antonioni for Time in 2007, the film writer Richard Corliss states that the film grossed "$20 million (about $120 million today) on a $1.8 million budget and helped liberate Hollywood from its puritanical prurience".[2]

The film earned $5.9 million in theatrical rentals in the United States and Canada in 1967.[23]

Critical reception

Reviews

Film critic Andrew Sarris said the movie was "a mod masterpiece". In Playboy magazine, film critic Arthur Knight wrote that Blowup would be "as important and seminal a film as Citizen Kane, Open City and Hiroshima, Mon Amour – perhaps even more so".[24] Time magazine called the film a "far-out, uptight and vibrantly exciting picture" that represented a "screeching change of creative direction" for Antonioni; the magazine predicted it would "undoubtedly be by far the most popular movie Antonioni has ever made".[25]

Bosley Crowther, film critic of The New York Times, called it a "fascinating picture,"[5] but expressed reservations, describing the "usual Antonioni passages of seemingly endless wanderings" as "redundant and long"; nevertheless, he called Blowup a "stunning picture – beautifully built up with glowing images and color compositions that get us into the feelings of our man and into the characteristics of the mod world in which he dwells".[5] Even film director Ingmar Bergman, who generally disliked Antonioni, called the film a masterpiece.[26]

Analysis

In an interview at the time of the film's release, Antonioni stated that the film "is not about man's relationship with man, it is about man's relationship with reality".[27] Anthony Quinn, writing for The Guardian, described Blowup as "a picture about perception and ambiguity," suggesting an association between elements of the film and the Zapruder film of the 1963 Kennedy assassination.[27] According to author Thomas Beltzer, the film explores the "inherently alienating" qualities of our media, where "the camera has turned us into passive voyeurs, programmable for predictable responses, ultimately helpless and even inhumanly dead".[3] Crowther of The New York Times stated that the film explores "the matter of personal involvement and emotional commitment in a jazzed-up, media-hooked-in world so cluttered with synthetic stimulations that natural feelings are overwhelmed".[5] Bilge Eberi of Houston Press notes the contrast between "the sinewy movements of the girls, their psychedelic jumpsuits and slinky dresses and multicolored minis," and "the blurred, frozen, inchoate unknowability of the death contained within his image," explaining that the photo "is a glimpse of the eternal and elemental – the dead body and the gun are both in the bushes, almost like a natural fact – that completely reorders, or rather disorders, Thomas' world. As an artist, he can't capture it or understand it or do anything with it. As an individual, he can't possess it or consume it."[8]

Roger Ebert described the film as "a hypnotic conjuring act, in which a character is awakened briefly from a deep sleep of bored alienation and then drifts away again. This is the arc of the film. Not 'Swinging London.' Not existential mystery. Not the parallels between what Hemmings does with his photos and what Antonioni does with Hemmings. But simply the observations that we are happy when we are doing what we do well, and unhappy seeking pleasure elsewhere. I imagine Antonioni was happy when he was making this film."[28] In his commentary for the DVD edition of the movie, Peter Brunette connects the film to the existentialist tenet that actions and experiences have no meaning per se, but are given a meaning within a particular context; this is especially borne out by the disposal of the broken guitar after the rock show: "He's rescued the object, this intensely meaningful object. Yet, out of the context, it's just a broken piece of a guitar [...] the important point here being that meaning, and the construction we put on reality, is always a group social function. And it's contextual."[29]

Accolades

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | 10 April 1967 | Best Director | Michelangelo Antonioni | Nominated | [30] |

| Best Original Screenplay | Michelangelo Antonioni, Tonino Guerra and Edward Bond | Nominated | |||

| British Academy Film Awards | 1968 | Best British Film | Michelangelo Antonioni | Nominated | [31] |

| Best Cinematography, Colour | Carlo Di Palma | Nominated | |||

| Best Art Direction, Colour | Assheton Gorton | Nominated | |||

| Cannes Film Festival | 27 April – 12 May 1967 | Grand Prix du Festival International du Film | Michelangelo Antonioni | Won | [32][33] |

| French Syndicate of Cinema Critics | 1968 | Best Foreign Film | Won | [34] | |

| Golden Globes | 15 February 1967 | Best English-Language Foreign Film | Blowup | Nominated | [35] |

| Nastro d'Argento | 1968 | Best Foreign Director | Michelangelo Antonioni | Won | [34] |

| National Society of Film Critics | January 1967 | Best Film | Blowup | Won | [36] |

| Best Director | Michelangelo Antonioni | Won |

See also

Notes

- ^ Several people known in 1966 are in the film; others became famous later. The most widely noted cameo was by The Yardbirds who perform "Stroll On" in the last third. Michelangelo Antonioni first asked Eric Burdon to play that scene but he turned it down. As Keith Relf sings, Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck play to either side along with Chris Dreja.

- ^ After Jeff Beck's guitar amplifier fails, he bashes his guitar to bits as The Who did at the time. Michelangelo Antonioni had wanted The Who in Blowup as he was fascinated by Pete Townshend's guitar-smashing routine.[37]

- ^ Steve Howe of Tomorrow recalled and wrote "We went on the set and started preparing for that guitar-smashing scene in the club. They even went as far as making up a bunch of Gibson 175 replicas and then we got dropped for The Yardbirds who were a bigger name. That's why you see Jeff Beck smashing my guitar rather than his!"[38] Michelangelo Antonioni also considered using The Velvet Underground (signed at the time to a division of MGM Records) in the nightclub scene but according to guitarist Sterling Morrison, "the expense of bringing the whole entourage to England proved too much for him".[39]

- ^ Janet Street-Porter can be seen dancing in a silver coat and red and yellow striped Carnaby Street trousers during the scene inside the nightclub.[40] A pre-Monty Python Michael Palin can also be seen in the motionless crowd watching The Yardbirds.[41]

References

- ^ a b c "Blowup (1967)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ a b c Corliss, Richard (5 August 2007). "When Antonioni Blew Up the Movies". Time. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Beltzer, Thomas (15 April 2005). "La Mano Negra: Julio Cortázar and His Influence on Cinema". Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ "Best of Bond". The Guardian. 21 January 2008. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Crowther, Bosley (19 December 1966). "Blow-Up". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Ryce, Walter (27 November 2013). "Ethan Russell's seminal '60s rock photos dazzle at Winfield Gallery in Carmel". montereycountyweekly.com. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ a b vbcsc03l@vax.csun.edu (snopes) (25 May 1993). "Re: The MPAA". The Skeptic Tank. The Skeptic Tank. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ebiri, Bilge (28 July 2017). "The Mysteries of Antonioni's Blow-Up, a Half Century on". Houston Press. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Votes for Blowup (1967)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- ^ PDN Legends Online: David Bailey Archived 22 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ "Yardbirds 1966 Blow Up," YouTube

- ^ Forn, Juan. "El rectángulo en la mano". Página 12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Tast, Brigitte; Tast, Hans-Jürgen (2014). light room – dark room. Antonionis "Blow-Up" und der Traumjob Fotograf. Schellerten: Kulleraugen. ISBN 978-3-88842-044-3.

- ^ McGlone, Neil McGlone. "Seventy Years of Cannes: Blow-Up in 1967". Criterion Collection. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ James, Simon R.H. (2007). London Film Location Guide. Batsford (London). p. 87. ISBN 978-0-7134-9062-6.

- ^ James (2007) p. 181.

- ^ "On the Trail of the Swinging Sixties – 'Blow-Up', Antonioni's Cult Film, Hit Our Screens 40 Years Ago. Robert Nurden Goes in Search of the Places Used for Filming, from Notting Hill to a Neglected Park in a Little-Known Corner of South-East London". The Independent. 10 September 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Blow-up: John Hooton's Photography Blog. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ James (2007) p. 38.

- ^ "Heddon Street, London" The Ziggy Stardust Companion. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ Birnbaum, Larry (2012). Before Elvis: The Prehistory of Rock 'n' Roll. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8629-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Antonioni's Corpse from "Blow-Up" speaks!". rogerebert.com. 10 February 1999. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1967". Variety. 3 January 1968. p. 25.

- ^ "Antonioni's Blowup Defines Cool". filminfocus.com. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ "Cinema: The Things Which Are Not Seen". Time. 30 December 1966. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ Interview published in Sydsvenska Dagbladet. "Bergman on Film Directors" Archived 26 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine at zakka.dk. Retrieved 25 December 2009.

- ^ a b Quinn, Anthony (10 March 2017). "Freedom, revolt and pubic hair: why Antonioni's Blow-Up thrills 50 years on". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (2002). The Great Movies. Broadway Books. p. 78. ISBN 0-7679-1038-9.

- ^ Commentary track by Peter Brunette on the 2005 DVD edition of Blow Up

- ^ "THE 39TH ACADEMY AWARDS". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Film in 1968". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Blowup". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- ^ "People: May 19, 1967". Time. 19 May 1967. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ a b Passafiume, Andrea. "Blow-Up (1966), AWARDS AND HONORS". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Blow-Up". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Platt, John; Dreja, Chris; McCarty, Jim (1983). Yardbirds. Sidgwick and Jackson (London). ISBN 978-0-283-98982-7.

- ^ Frame, Pete (1993). The Complete Rock Family Trees. Omnibus Press (London; New York City). p. 55. ISBN 978-0-711-90465-1.

- ^ Bockris, Victor and Malanga, Gerard (1983). Uptight – The Velvet Underground Story. Quill (New York). p. 67. ISBN 978-0-688-03906-6.

- ^ Hemmings, David (2004). Blow-up and other exaggerations. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-86105-789-1.

- ^ Dennis, Jon (24 November 2011). "My favourite film: Blow-Up". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

Bibliography

- Brunette, Peter (2005). DVD Audio Commentary (Iconic Films).

- Hemmings, David (2004). Blow-Up… and Other Exaggerations – The Autobiography of David Hemmings. Robson Books (London). ISBN 978-1-861-05789-1.

- Huss, Roy, ed. (1971). Focus on Blow-Up. Film Focus. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-13-077776-8. Includes a translation of Cortázar's original short story.

External links

- Blowup at IMDb

- Blowup at the TCM Movie Database

- Blowup at AllMovie

- Blowup at Rotten Tomatoes

- Where Did They Film That? – film entry

- Peter Bowles on making of Blow-Up

- Blowup Then & Now website

- On the set of Antonioni's Blow-Up and how this film about a '60s fashion photographer compared to the real thing.

- Blow-Up: In the Details an essay by David Forgacs at the Criterion Collection

- 1966 films

- 1960s mystery thriller films

- 1960s psychological thriller films

- 1960s thriller drama films

- American films

- American mystery drama films

- American mystery thriller films

- American psychological thriller films

- American thriller drama films

- British films

- British mystery drama films

- British mystery thriller films

- British psychological thriller films

- British thriller drama films

- Cameras in fiction

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- English-language films

- Films about fashion photographers

- Films directed by Michelangelo Antonioni

- Films based on short fiction

- Films produced by Carlo Ponti

- Films scored by Herbie Hancock

- Films set in London

- Films shot in London

- Films with screenplays by Edward Bond

- Films with screenplays by Tonino Guerra

- Italian films

- Italian mystery thriller films

- Italian psychological thriller films

- Italian thriller drama films

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Palme d'Or winners

- 1966 drama films

- National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Film winners