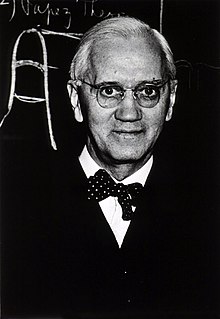

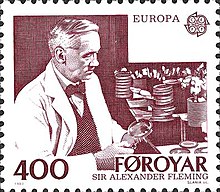

Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming (August 6, 1881 – March 11, 1955) was a Scottish biologist and pharmacologist. Fleming published many articles on bacteriology, immunology, and chemotherapy. His most well known achievements are the discovery of the enzyme lysozyme in 1922 and isolation of the antibiotic substance penicillin from the fungus Penicillium notatum in 1928, for which he shared a Nobel Prize with Florey and Chain.[1].

Birth and education

Fleming was born on a farm at Lochfield near Darvel in East Ayrshire, went to the local school, and then for two years at the Kilmarnock Academy. After working in a shipping office for four years, 20 year old Fleming inherited some money from an uncle. (For the story about his father rescuing a boy, see the section fable ). His older brother, Tom, was already a doctor and suggested the same career, and so in 1901, he enrolled at St Mary's Hospital, London. He qualified for the school with distinction in 1906 and had the option of becoming a surgeon. By chance, however, he had been a member of the rifle club (he had been an active member of the Territorial Army since 1900). The captain of the club, wishing to retain Fleming in the team suggested that he join the research department at St Mary's, where he became assistant bacteriologist to Sir Almroth Wright, a pioneer in vaccine therapy and immunology. He gained M.B. and then B.Sc. with Gold Medal in 1908, and became a lecturer at St. Mary's until 1914. He served throughout World War I as a captain in the Army Medical Corps, and was mentioned in dispatches. He and many of his colleagues worked in battlefield hospitals at the Western Front in France. In 1918 he returned to St.Mary's Hospital, which was a teaching hospital. He was elected Professor of Bacteriology at the School in 1928.

Work before penicillin

After the war Fleming looked for anti-bacterial agents, because he had witnessed the death of many soldiers from septicemia. Unfortunately antiseptics killed the patient's immunological defences faster than they killed the invading bacteria. In an article in The Lancet during WWI, Fleming described an ingenious experiment, which he was able to do due to his own glass blowing skills, which explained why antiseptics were killing more soldiers than the diseases themselves during WWI. Antiseptics worked well on the skin, but deep wounds had a tendency to shelter anaerobic bacteria, and antiseptics mainly seemed to remove beneficial agents that actually protected the patients in these cases. Sir Almroth Wright strongly supported Fleming's findings. Despite this, most army physicians during WWI continued to use antiseptics even in cases where this worsened the condition of the patients.

In 1922, Fleming discovered lysozyme, the "body's own antibiotic", and that it has weak anti-bacterial properties.

Accidental discovery

Fleming was not the first to notice the antibiotic properties of molds and fungi. See Discoveries of anti-bacterial effects of penicillium moulds before Fleming.

By 1928, he was investigating the properties of staphylococci. He was already well known by then due to his earlier work, and known to be a brilliant but careless researcher; cultures that he worked on were often forgotten and his lab was usually in chaos. After returning from a long vacation, Fleming noticed that many of his culture dishes were contaminated with a fungus and so threw the dishes in disinfectant. He had to show a visitor what he had been doing and retrieved some of the unsubmerged dishes. He then noticed a zone around a fungus where the bacteria had not grown. Fleming isolated an extract from the mould, correctly identified it as from the pencillium family and named the agent, penicillin.

He investigated its effect on many bacteria successfully, and noticed that it affected bacteria such as staphylococci and all Gram-positive pathogenes (scarlet fever, pneumonia, gonorrhea, meningitis, diphteria ) but not typhoid or paratyphoid, to which he was looking for a cure at the time.

Fleming published his discovery in 1929 in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology, but little attention was paid to the paper. Fleming continued his investigations but found that it was difficult to grow penicillium mould and having made it, it was even more difficult to refine it. Fleming's impression was that, because of the problem of producing it in quantity and because its action seemed slow, penicillin would not be an important in treating infection. Fleming also became convinced that penicillin would not last long enough in the human body to kill bacteria. Many clinical tests were inconclusive, probably since they used it as an antiseptic. In 1933 he dramatically cured Keith Rogers and suddenly he had a notable clinical case to show that might interest a chemist to further pursue the goal of developing a stable form of penicillin. At the same time as doing other research, he continued until 1940 to try and interest a chemist skilled enough to achieve this.

Purification to a stable form and industrial scale production

Howard Florey led a large team of scientists at Sir William Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford. The team had previously done work with Fleming's Lysozyme and Florey had read Fleming's paper that described the antibacterial effects of penicillin. In 1938 he chose to try to purify three promising substances, hoping that at least one of them might prove useful. One of the three substances was penicillin.

Ernst Chain worked out how to isolate and concentrate penicillin. He also correctly theorized the structure of penicillin. Shortly after the team published their first results in 1940, Fleming turned up and asked to see what they had done. When Chain asked who he was and Fleming told him his name Chain exclaimed "I thought you were dead!".

Norman Heatley suggested transferring the active ingredient of penicillin back into water by changing its acidity. This produced enough of the drug to begin testing on animals.

Sir Henry Harris said in 1998: "Without Fleming, no Chain or Florey; without Chain, no Florey; without Florey, no Heatley; without Heatley, no penicillin." There were many more people involved in the Oxford team, and at one point the entire Dunn School was involved in its production.

After the team had developed a method of purifying penicillin to an effective first stable form in 1940, several clinical trials ensued, and their amazing success inspired the team to develop methods for mass production and mass distribution in 1945.

Fleming was modest about his part in the development of penicillin, describing his fame as the "Fleming Myth" and he praised Florey and Chain for transforming the laboratory curiosity into a practical drug. Fleming was the first to isolate the active substance, giving him the privilege of naming it: penicillin. He also kept, grew and distributed the original mould for twelve years, and continued until 1940 to try to get help from any chemist that had enough skill to make a stable form of it for mass production. There were many failed attempts around Fleming towards stabilising the substance before Florey organized his large and very skilled biochemical research team in 1938 at Oxford to undertake the immense and innovative work that had to be done to produce a stable 'mass produce-able' penicillin.

Antibiotics

Fleming's accidental discovery and isolation of penicillin in September 1928 marks the start of modern Antibiotics.

Fleming also discovered very early that bacteria developed Antibiotic resistance whenever too little penicillin was used or when it was used for too short a period.

Almroth Wright had predicted the Antibiotic resistance even before it was noticed during experiments.

Fleming cautioned about the use of penicillin in his many speeches around the world. He cautioned not to use penicillin unless there was a properly diagnosed reason for it to be used, and that if it were used, never to use too little, or for too short a period, since these are the circumstances under which Antibiotic resistance to bacteria develop.

Accolades

- Fleming, Florey, and Chain jointly received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1945. According to the rules of the Nobel committee a maximum of three people may share the prize.

- Fleming was knighted in 1944.

- Florey received the greater honour of a peerage for his monumental work in making penicillin available to the public and saving millions of lives in World War II, becoming a Baron.

- Fleming was ranked #43 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

- The discovery of penicillin was ranked as the most important discovery of the millennium when the year 2000 was approaching by at least 3 large Swedish magazines[2]. It is impossible to know how many lives have been saved by this discovery, but some of these magazines placed their estimate near 200 million lives.

- Kevin Brown's biography contains a list with hundreds prizes and honours given to Fleming.

Other information

In 1915, Fleming married Sarah Marion McElroy of Killala, Ireland, who died in 1949. Their son became a general medical practitioner.

After Sarah's death, Fleming married Dr. Amalia Koutsouri-Voureka, a Greek colleague at St. Mary's in 1953.

Fleming was long a member of the Chelsea Arts Club, a private club for artists of all genres, founded in 1891 at the suggestion of the painter James McNeil Whistler. Fleming was admitted to the club after he made "germ paintings," in which he drew with a culture loop using spores of highly pigmented bacteria. The bacteria were invisible while he painted, but when cultured made bright colours.

- Serratia marcescens - red

- Chromobacterium violaceum - purple

- Micrococcus luteus - yellow

- Micrococcus varians - white

- Micrococcus roseus - pink

- Bacillus sp. - purple

Fable

The popular story of Winston Churchill's father's paying for Fleming's education after Fleming's father saved young Winston from death is false. According to the biography, "Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution" by Kevin Brown, Alexander Fleming is quoted as saying that this was "a wonderful fable". Nor did he save Winston Churchill himself during WWII. Churchill was saved by Lord Moran, using sulphonamides, since he had no experience with penicillin, when Churchill fell ill in Carthage in Tunisia in 1943. The Daily Telegraph and The Morning Post on 21 December 1943 wrote that he had been saved by penicillin. It is probable that, as sulphonamide was a German discovery, and there was a war with Germany, that the patriotic pride in the miracle cure of penicillin had something to do with this error in reporting.

Death

Fleming died in 1955 of a heart attack at the age of 73. He was buried as a national hero in the crypt of St. Paul's Cathedral in London. His discovery of penicillin had changed the world of modern medicines by introducing the age of useful antibiotics and his discovery of the penicillin has saved and is still saving millions of people.

Biographies

- Penicillin Man: Alexander Fleming and the Antibiotic Revolution, by Kevin Brown, St Mary's Trust Archivist and Alexander Fleming Laboratory Museum Curator. (2004) ISBN 0750931523 (Most of the information in this article comes from this book)

- Alexander Fleming, the Man and the Myth (1984) by Gwyn Macfarlane

- The Life of Sir Alexander Fleming (1959) by André Maurois

- Fleming, Discoverer of Penicillin (1952) by Laurence James Ludovici

Other books

- The Cambridge Illustrated History of Medicine. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1996. Porter, Roy, ed.

- An Outline History of Medicine. London: Butterworths, 1985. Rhodes, Philip.

- Nobel Lectures, Physiology or Medicine 1942-1962, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1964

External links

References

- ^ "Sir Alexander Fleming – Biography". Nobel. 1945-12-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Greatest Hero of the Millennium". Ny Teknik. 1999-12-16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

On Lysosome:

(Fleming A. On a remarkable bacteriolytic element found in tissues and secretions. Proc Roy Soc Ser B 1922;93:306-17).