Ancient Greek coinage

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2007) |

The history of Ancient Greek coinage can be divided (along with most other Greek art forms) into four periods, the Archaic, the Classical, the Hellenistic and the Roman. The Archaic period extends from the introduction of coinage to the Greek world during the 7th century BC until the Persian Wars in about 480 BC. The Classical period then began, and lasted until the conquests of Alexander the Great in about 330 BC, which began the Hellenistic period, extending until the Roman absorption of the Greek world in the 1st century BC. The Greek cities continued to produce their own coins for several more centuries under Roman rule. The coins produced during this period are called Roman provincial coins or Greek Imperial Coins. Ancient Greek coins of all four periods span over a period of more than ten centuries.

Weight standards and denominations

The basic standards of the Ancient Greek monetary system were the Attic standard, based on the Athenian drachma of 4.3 grams of silver and the Corinthian standard based on the stater of 8.6 grams of silver, that was subdivided into three silver drachmas of 2.9 grams.[2] The word drachm(a) means "a handful", literally "a grasp".[1] Drachmae were divided into six obols (from the Greek word for a spit[3]), and six spits made a "handful". This suggests that before coinage came to be used in Greece, spits in prehistoric times were used as measures of daily transaction. In archaic/pre-numismatic times iron was valued for making durable tools and weapons, and its casting in spit form may have actually represented a form of transportable bullion, which eventually became bulky and inconvenient after the adoption of precious metals. Because of this very aspect, Spartan legislation famously forbade issuance of Spartan coin, and enforced the continued use of iron spits so as to discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. In addition to its original meaning (which also gave the euphemistic diminutive "obelisk", "little spit"), the word obol (ὀβολός, obolós, or ὀβελός, obelós) was retained as a Greek word for coins of small value, still used as such in Modern Greek slang (όβολα, óvola, "monies").

The obol was further subdivided into tetartemorioi (singular tetartemorion) which represented 1/4 of an obol, or 1/24 of a drachm. This coin (which was known to have been struck in Athens, Colophon, and several other cities) is mentioned by Aristotle as the smallest silver coin.[4]: 237 Various multiples of this denomination were also struck, including the trihemitetartemorion (literally three half-tetartemorioi) valued at 3/8 of an obol.[4]: 247

Archaic period

The first known coins were issued in either Lydia or Ionia in Asia Minor at some time before 600 BC, either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own use or perhaps because Greek mercenaries wanted to be paid in precious metal at the conclusion of their time of service, and wanted to have their payments marked in a way that would authenticate them. These coins were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver that was highly prized and abundant in that area. By the middle of the 6th century BC, technology had advanced, making the production of pure gold and silver coins simpler. Accordingly, King Croesus introduced a bi-metallic standard that allowed for coins of pure gold and pure silver to be struck and traded in the marketplace.

The Greek world was divided into more than two thousand self-governing city-states (in Greek, poleis), and more than half of them issued their own coins. Some coins circulated widely beyond their polis, indicating that they were being used in inter-city trade; the first example appears to have been the silver stater or didrachm of Aegina that regularly turns up in hoards in Egypt and the Levant, places which were deficient in silver supply. As such coins circulated more widely, other cities began to mint coins to this "Aeginetan" weight standard of (6.1 grams to the drachm), other cities included their own symbols on the coins. This is not unlike present day Euro coins, which are recognisably from a particular country, but usable all over the Euro zone.

Athenian coins, however, were struck on the "Attic" standard, with a drachm equaling 4.3 grams of silver. Over time, Athens' plentiful supply of silver from the mines at Laurion and its increasing dominance in trade made this the pre-eminent standard. These coins, known as "owls" because of their central design feature, were also minted to an extremely tight standard of purity and weight. This contributed to their success as the premier trade coin of their era. Tetradrachms on this weight standard continued to be a widely used coin (often the most widely used) through the classical period. By the time of Alexander the Great and his Hellenistic successors, this large denomination was being regularly used to make large payments, or was often saved for hoarding.

Classical period

The Classical period saw Greek coinage reach a high level of technical and aesthetic quality. Larger cities now produced a range of fine silver and gold coins, most bearing a portrait of their patron god or goddess or a legendary hero on one side, and a symbol of the city on the other. Some coins employed a visual pun: some coins from Rhodes featured a rose, since the Greek word for rose is rhodon. The use of inscriptions on coins also began, usually the name of the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily produced some especially fine coins. The large silver decadrachm (10-drachm) coin from Syracuse is regarded by many collectors as the finest coin produced in the ancient world, perhaps ever. Syracusan issues were rather standard in their imprints, one side bearing the head of the nymph Arethusa and the other usually a victorious quadriga. The tyrants of Syracuse were fabulously rich, and part of their public relations policy was to fund quadrigas for the Olympic chariot race, a very expensive undertaking. As they were often able to finance more than one quadriga at a time, they were frequent victors in this highly prestigious event. Syracuse was one of the epicenters of numismatic art during the classical period. Led by the engravers Kimon and Euainetos, Syracuse produced some of the finest coin designs of antiquity.

Amongst the first centers to produce coins during the Greek colonization of mainland Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) were Paestum, Crotone, Sybaris, Caulonia, Metapontum and Taranto. These ancient cities started producing coins from 550BC to 510BC.[5][6]

Hellenistic period

The Hellenistic period was characterized by the spread of Greek culture across a large part of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms were established in Egypt and Syria, and for a time also in Iran and as far east as what is now Afghanistan and northwestern India. Greek traders spread Greek coins across this vast area, and the new kingdoms soon began to produce their own coins. Because these kingdoms were much larger and wealthier than the Greek city states of the classical period, their coins tended to be more mass-produced, as well as larger, and more frequently in gold. They often lacked the aesthetic delicacy of coins of the earlier period.

Still, some of the Greco-Bactrian coins, and those of their successors in India, the Indo-Greeks, are considered the finest examples of Greek numismatic art with "a nice blend of realism and idealization", including the largest coins to be minted in the Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by Eucratides (reigned 171–145 BC), the largest silver coin by the Indo-Greek king Amyntas Nikator (reigned c. 95–90 BC). The portraits "show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland depictions of their royal contemporaries further West" (Roger Ling, "Greece and the Hellenistic World").

The most striking new feature of Hellenistic coins was the use of portraits of living people, namely of the kings themselves. This practice had begun in Sicily, but was disapproved of by other Greeks as showing hubris (arrogance). But the kings of Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria had no such scruples: having already awarded themselves with "divine" status, they issued magnificent gold coins adorned with their own portraits, with the symbols of their state on the reverse. The names of the kings were frequently inscribed on the coin as well. This established a pattern for coins which has persisted ever since: a portrait of the king, usually in profile and striking a heroic pose, on the obverse, with his name beside him, and a coat of arms or other symbol of state on the reverse.

Minting

All Greek coins were handmade, rather than machined as modern coins are. The design for the obverse was carved (in incuso) into a block of bronze or possibly iron, called a die. The design of the reverse was carved into a similar punch. A blank disk of gold, silver, or electrum was cast in a mold and then, placed between these two and the punch struck hard with a hammer, raising the design on both sides of the coin.[7]

Coins as a symbol of the city-state

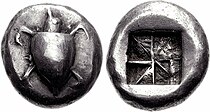

Coins of Greek city-states depicted a unique symbol or feature, an early form of emblem, also known as badge in numismatics, that represented their city and promoted the prestige of their state. Corinthian stater for example depicted pegasus the mythological winged stallion, tamed by their hero Bellerophon. Coins of Ephesus depicted the bee sacred to Artemis. Drachmas of Athens depicted the owl of Athena. Drachmas of Aegina depicted a chelone. Coins of Selinunte depicted a "selinon" (σέλινον[8] - celery). Coins of Heraclea depicted Heracles. Coins of Gela depicted a man-headed bull, the personification of the river Gela. Coins of Rhodes depicted a "rhodon" (ῥόδον[9] - rose). Coins of Knossos depicted the labyrinth or the mythical creature minotaur, a symbol of the Minoan Crete. Coins of Melos depicted a "mēlon" (μήλον - apple). Coins of Thebes depicted a Boeotian shield.

Commemorative coins

The use of commemorative coins to celebrate a victory or an achievement of the state was a Greek invention. Coins are valuable, durable and pass through many hands. In an age without newspapers or other mass media, they were an ideal way of disseminating a political message. The first such coin was a commemorative decadrachm issued by Athens following the Greek victory in the Persian Wars. On these coins that were struck around 480 BC, the owl of Athens, the goddess Athena's sacred bird, was depicted facing the viewer with wings outstretched, holding a spray of olive leaves, the olive tree being Athena's sacred plant and also a symbol of peace and prosperity.[10] The message was that Athens was powerful and victorious, but also peace-loving. Another commemorative coin, a silver dekadrachm known as " Demareteion", was minted at Syracuse at approximately the same time to celebrate the defeat of the Carthaginians. On the obverse it bears a portrait of Arethusa or queen Demarete.

Ancient Greek coins today

Collections of Ancient Greek coins are held by museums around the world, of which the collections of the British Museum, the American Numismatic Society, and the Danish National Museum are considered to be the finest. The American Numismatic Society collection comprises some 100,000 ancient Greek coins from many regions and mints, from Spain and North Africa to Afghanistan. To varying degrees, these coins are available for study by academics and researchers.

There is also an active collector market for Greek coins. Several auction houses in Europe and the United States specialize in ancient coins (including Greek) and there is also a large on-line market for such coins.

Hoards of Greek coins are still being found in Europe, Middle East, and North Africa, and some of the coins in these hoards find their way onto the market. Due to the numbers in which they were produced, the durability of the metals, and the ancient practice of burying large numbers of coins to save them, coins are an ancient art within the reach of ordinary collectors.

See also

- Art of Ancient Greece

- Indian coinage

- Philippeioi

- Seleucid coinage

- Silver stater with a turtle, early coin

Citations

- ^ a b Entry δράσσομαι in LSJ, cf: δράξ (drax), δραχμή (drachmē): grasp with the hand

- ^ BMC 11 - Attica Megaris Aegina

- ^ "Obol". Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ a b American Numismatic Society (1916). American Journal of Numismatics. Vol. 49–50. American Numismatic and Archaeological Society.

- ^ "Bruttium - Ancient Greek Coins - WildWinds.com". Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ "Lucania - Ancient Greek Coins - WildWinds.com". Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ^ Grierson: Numismatics

- ^ Entry σέλινον at LSJ

- ^ Entry ῥόδον at LSJ

- ^ "Decadrachm". Flickr. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

Further reading

- Grierson, Philip (1975), Numismatics, Oxford, Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-885098-0

- Head, Barclay V. (1911), Historia Numorum; A Manual of Greek Numismatics, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hill, George Francis (1906), Historical Greek Coins, London : Archibald Constable and Co.

- Jenkins, H.K. (1990), Ancient Greek Coins, Seaby, ISBN 1-85264-014-6

- Konuk, Koray (2003), From Kroisos to Karia; Early Anatolian Coins from the Muharrem Kayhan Collection, ISBN 975-8070-61-4

- Kraay, Colin M. (1976), Archaic and Classical Greek Coins, New York: Sanford J. Durst, ISBN 0-915262-75-4.

- Melville Jones, John R, 'A Dictionary of Ancient Greek Coins', London, Seaby 1986, reprinted Spink 2004.

- Melville Jones, John R, Testimonia Numaria. Greek and Latin texts concerning Ancient Greek Coinage, 2 vols (1993 and 2007), London, Spink, 0-907-05-40-0 and 978-1-902040-81-3.

- Ramage, Andrew and Craddock, Paul (2000), King Croesus' Gold; Excavations at Sardis and the History of Gold Refining, Trustees of the British Museum, ISBN 0-7141-0888-X.

- Rutter N. K, Burnett A. M, Crawford M. H, Johnston A. E.M, Jessop Price M (2001), Historia Numorum Italy, London: The British Museum Press, ISBN 0-7141-1801-X.

- Sayles, Wayne G, Ancient Coin Collecting, Iola, Wisconsin : Krause Publications, 2003.

- Sayles, Wayne G, Ancient Coin Collecting II: Numismatic Art of the Greek World", Iola, Wisconsin : Krause Publications, 2007.

- Sear, David, "Greek Coins and Their Values: Volume 1", London: Spink.

- Sear, David, "Greek Coins and Their Values: Volume 2" London: Spink.

- Seltman, Charles (1933), Greek Coins, London: Methuen & Co, Ltd.

- Seltman, Charles, Masterpieces of Greek Coinage, Bruno Cassirer - Oxford, 1949.

- Thompson M, Mørkholm O, Kraay C. M. (eds): An Inventory of Greek Coin Hoards, (IGCH). New York, 1973 ISBN 978-0-89722-068-2

- Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum:

- American Numismatic Society: The Collection of the American Numismatic Society, New York

- Ward, John, Greek Coins and their Parent Cities, London : John Murray, 1902. (accompanied by a catalogue of the author’s collection by Sir George Francis Hill)

External links

- International Numismatic Commission

- The British Academy

- Sylloge Nummorum Graecorum in UK

- American Numismatic Society

- Perseus Project at Tuft University

- Wildwinds: a database for Greek and Roman coins - includes images

- CoinArchives.com: A large database of coins previously sold at auction - includes images and prices

- National Numismatic Museum, Athens

- Historia Numorum: A Manual of Greek Numismatics

- Hellenic Numismatic Society

- History of the Greek coins And presentation of the Greek modern coins

- Online numismatic exhibit: "This round gold is but the image of the rounder globe" (H.Melville). The charm of gold in ancient coinage

- Digital Library Numis (DLN) Online books and articles on Greek coins

- Asia Minor Coins History and index/photo gallery of ancient Greek and Roman coins from Asia Minor (Anatolia/Turkey)