Bessarabia

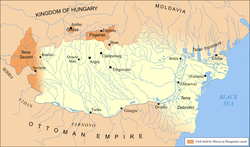

Bessarabia (Template:Lang-ro; Template:Lang-ru, Bessarabiya; Template:Lang-tr; Template:Lang-uk, Bessarabiya; Template:Lang-bg Besarabiya) is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. Today Bessarabia is mostly (approx. 65%) part of the modern-day Moldova, with the Ukrainian Budjak region covering the southern coastal region and part of the Ukrainian Chernivtsi Oblast covering a small area in the north.

In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812), and the ensuing Peace of Bucharest, the eastern parts of the Principality of Moldavia, an Ottoman vassal, along with some areas formerly under direct Ottoman rule, were ceded to Imperial Russia. The acquisition was among the Empire's last territorial acquisitions in Europe. The newly acquired territories were organised as the Governorate of Bessarabia, adopting a name previously used for the southern plains, between the Dniester and the Danube rivers. Following the Crimean War, in 1856, the southern areas of Bessarabia were returned to Moldavian rule; Russian rule was restored over the whole of the region in 1878, when Romania, the result of Moldavia's union with Wallachia, was pressured into exchanging those territories for the Dobruja.

In 1917, in the wake of the Russian Revolution, the area constituted itself as the Moldavian Democratic Republic, an autonomous republic part of a proposed federative Russian state. Bolshevik agitation in late 1917 and early 1918 resulted in the intervention of the Romanian Army, ostensibly to pacify the region. Soon after, the parliamentary assembly declared independence, and then union with the Kingdom of Romania.[1] The legality of these acts was however disputed, most prominently by the Soviet Union, which regarded the area as a territory occupied by Romania.

In 1940, after securing the assent of Nazi Germany through the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the Soviet Union pressured Romania into withdrawing from Bessarabia, allowing the Red Army to retake the region. The area was formally integrated into the Soviet Union: the core joined parts of the Moldavian ASSR to form the Moldavian SSR, while territories inhabited by Slavic majorities in the north and the south of Bessarabia were transferred to the Ukrainian SSR. Axis-aligned Romania briefly recaptured the region in 1941 during the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, but lost it in 1944 as the tide of war changed. In 1947, the Soviet-Romanian border along the Prut was internationally recognised by the Paris Treaty that ended World War II.

During the process of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Moldavian and Ukrainian SSRs proclaimed their independence in 1991, becoming the modern states of Moldova and Ukraine, while preserving the existing partition of Bessarabia. Following a short war in the early 1990s, Transnistria proclaimed itself the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic, separate from the government of the Republic of Moldova, extending its authority also over the municipality of Bender in Bessarabia. Part of the Gagauz-inhabited areas in the southern Bessarabia was organised in 1994 as an autonomous region within Moldova.

Etymology

According to the traditional interpretation, the name Bessarabia (Basarabia in Romanian) derives from the Wallachian Basarab dynasty, who allegedly ruled over the southern part of the area in the 14th century. Recent research has however cast doubt on this view, as the name was first applied to the territory by Western cartographers, showing up in local sources only in the second half of the 17th century. Furthermore, the use of the term to refer to the Moldavian lands near the Black Sea was explicitly rejected as a cartographic confusion by the early Moldavian chronicler Miron Costin. The confusion may have been caused by Polish references to Wallachia as Bessarabia, wrongly interpreted by medieval Western cartographers as a separate land between that country and Moldavia.[2] According to Dimitrie Cantemir, the name originally applied only to the part of the territory south of the Upper Trajanic Wall, somewhat bigger than current Budjak. The name Bessarabia may literally mean "Bessi slaves" (?) after the Thracian tribe which was expelled by Trajan north of the Danube.[citation needed]

Geography

The region is bounded by the Dniester to the north and east, the Prut to the west and the lower River Danube and the Black Sea to the south. It has an area of 45,630 km2 (17,620 sq mi).[3] The area is mostly hilly plains with flat steppes. It is very fertile, and has lignite deposits and stone quarries. People living in the area grow sugar beet, sunflowers, wheat, maize, tobacco, wine grapes and fruit. They also raise sheep and cattle. Currently, the main industry in the region is agricultural processing.

The region's main cities are Chișinău (the former capital of Bessarabia Governorate, nowadays the capital of Moldova), Izmail and Bilhorod-Dnistrovs'kyi, historically called Cetatea Albă / Akkerman (nowadays both in Ukraine). Other towns of administrative or historical importance include: Khotyn, Reni and Kilia (nowadays all in Ukraine), and Lipcani, Briceni, Soroca, Bălți, Orhei, Ungheni, Bender/Tighina and Cahul (nowadays all in Moldova).

History

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

In the late 14th century, the newly established Principality of Moldavia encompassed what later became known as Bessarabia. Afterwards, this territory was directly or indirectly, partly or wholly controlled by: the Ottoman Empire (as suzerain of Moldavia, with direct rule only in Budjak and Khotin), Russian Empire, Romania, the USSR. Since 1991, most of the territory forms the core of Moldova, with smaller parts in Ukraine.

Prehistory

The territory of Bessarabia has been inhabited by people for thousands of years. Cucuteni-Trypillian culture flourished between the 6th and 3rd millennium BC. The Indo-European culture spread in the region around 2000 BC.

Ancient times

In Antiquity the region was inhabited by Thracians, as well as for various shorter periods Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, and Celts, specifically by tribes such as Costoboci, Carpi, Britogali, Tyragetae, and Bastarnae.[4] In the 6th century BC, Greek settlers established the colony of Tyras, along the Black Sea coast and traded with the locals. Also, Celts settled in the southern parts of Bessarabia, their main city being Aliobrix.

The first polity that is believed to have included the whole of Bessarabia was the Dacian polity of Burebista in the 1st century BC. After his death, the polity was divided into smaller pieces, and the central parts were unified in the Dacian kingdom of Decebalus in the 1st century AD. This kingdom was defeated by the Roman Empire in 106. Southern Bessarabia was included in the empire even before that, in 57 AD, as part of the Roman province Moesia Inferior, but it was secured only when the Dacian Kingdom was defeated in 106. The Romans built defensive earthen walls in Southern Bessarabia (e.g. Lower Trajan Wall) to defend the Scythia Minor province against invasions. Except for the Black Sea shore in the south, Bessarabia remained outside direct Roman control; the myriad of tribes there are called by modern historians Free Dacians.[5] The 2nd to the 5th centuries also saw the development of the Chernyakhov culture.

In 270, the Roman authorities began to withdraw their forces south of the Danube, especially from the Roman Dacia, due to the invading Goths and Carpi. The Goths, a Germanic tribe, poured into the Roman Empire from the lower Dniepr River, through the southern part of Bessarabia (Budjak steppe), which due to its geographic position and characteristics (mainly steppe), was swept by various nomadic tribes for many centuries. In 378, the area was overrun by the Huns.

Early Middle Ages

From the 3rd century until the 11th century, the region was invaded numerous times in turn by different tribes: Goths, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans and Mongols. The territory of Bessarabia was encompassed in dozens of ephemeral kingdoms which were disbanded when another wave of migrants arrived. Those centuries were characterized by a terrible state of insecurity and mass movement of these tribes. The period was later known as the "Dark Ages" of Europe, or Age of migrations.

In 561, the Avars captured Bessarabia and executed the local ruler Mesamer. Following Avars, Slavs started to arrive in the region and establish settlements. Then, in 582, Onogur Bulgars settled in southeastern Bessarabia and northern Dobruja, from which they moved to Moesia Inferior (allegedly under pressure from the Khazars), and formed the nascent region of Bulgaria. With the rise of the Khazars' state in the east, the invasions began to diminish and it was possible to create larger states. According to some opinions, the southern part of Bessarabia remained under the influence of the First Bulgarian Empire until to the end of the 9th century.

Between the 8th and 10th centuries, the southern part of Bessarabia was inhabited by people from Balkan-Dunabian culture[6] (the culture of the First Bulgarian Empire). Between the 9th and 13th centuries, Bessarabia is mentioned in Slav chronicles as part of Bolohoveni (north) and Brodnici (south) voivodeships, believed[by whom?] to be Vlach principalities of the early Middle Ages.

The last large scale invasions were those of the Mongols of 1241, 1290, and 1343. Sehr al-Jedid (near Orhei), an important settlement of the Golden Horde, dates from this period. They led to a retreat of a big part of the population to the mountainous areas in Eastern Carpathians and to Transylvania. Especially low became the population east of Prut at the time of the Tatar invasions.

In the Late Middle Age, chronicles mention a Tigheci "republic", predating the establishment of the Principality of Moldavia, situated near the modern town of Cahul in the southwest of Bessarabia, preserving its autonomy even during the later Principality even into the 18th century. Genovese merchants rebuilt or established a number of forts along Dniester (notably Moncastro) and Danube (including Kyliya/Chilia-Licostomo).[citation needed]

Principality of Moldavia

After the 1360s the region was gradually included in the principality of Moldavia, which by 1392 established control over the fortresses of Akkerman and Chilia, its eastern border becoming the River Dniester. In the latter part of the 14th century, the southern part of the region was for several decades part of Wallachia. The main dynasty of Wallachia was called Basarab, from which the current name of the region originated. In the 15th century, the entire region was a part of the principality of Moldavia. Stephen the Great ruled between 1457 and 1504, a period of nearly 50 years during which he won 32 battles defending his country against virtually all his neighbours (mainly the Ottomans and the Tatars, but also the Hungarians and the Poles), while losing only two. During this period, after each victory, he raised a monastery or a church close to the battlefield honoring Christianity. Many of these battlefields and churches, as well as old fortresses, are situated in Bessarabia (mainly along Dniester).

In 1484, the Turks invaded and captured Chilia and Cetatea Albă (Akkerman in Turkish), and annexed the shoreline southern part of Bessarabia, which was then divided into two sanjaks (districts) of the Ottoman Empire. In 1538, the Ottomans annexed more Bessarabian land in the south as far as Tighina, while the central and northern Bessarabia remained part of the Principality of Moldavia (which became a vassal of the Ottoman Empire). Between 1711 and 1812, the Russian Empire occupied the region five times during its wars against Ottoman and Austrian Empires.

Annexation by the Russian Empire

By the Treaty of Bucharest of May 28, 1812—concluding the Russo-Turkish War, 1806-1812—the Ottoman Empire ceded the land between the Pruth and the Dniester, including both Moldavian and Turkish territories, to the Russian Empire. That entire region was then called Bessarabia.[7]

In 1814, the first German settlers arrived and mainly settled in the southern parts and Bessarabian Bulgarians began settling in the region too, founding towns such as Bolhrad. Between 1812 and 1846, the Bulgarian and Gagauz population migrated to the Russian Empire via the River Danube, after living many years under oppressive Ottoman rule, and settled in southern Bessarabia. Turkic-speaking tribes of the Nogai horde also inhabited the Budjak Region (in Turkish Bucak) of southern Bessarabia from the 16th to 18th centuries, but were totally driven out prior to 1812.

Administratively, Bessarabia became an oblast of the Russian Empire in 1818, and a guberniya in 1873.

By the Treaty of Adrianople that concluded the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829 the entire Danube Delta was added to the Bessarabian oblast.[citation needed] In 1834, Romanian language was banned from schools and government facilities, despite 80% of the population speaking the language. This would eventually lead to the banning of Romanian in churches, media and books. Those who protested the banning of Romanian could be sent to Siberia.[8]

Southern Bessarabia returned to Moldavia

At the end of the Crimean War, in 1856, by the Treaty of Paris, southern Bessarabia (later organised as the Cahul, Bolgrad, and Ismail counties) was returned to Moldavia, causing the Russian Empire to lose access to the Danube river.

In 1859, Moldavia and Wallachia united to form the Romanian United Principalities (Romania), which included the southern part of Bessarabia.

The railway Chișinău-Iași was opened on June 1, 1875 in preparation for the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and the Eiffel Bridge was opened on April 21 [O.S. April 9] 1877, just three days before the outbreak of the war. The Romanian War of Independence was fought in 1877–78, with the help of the Russian Empire as an ally. Northern Dobruja was awarded to Romania for its role in the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War, and as compensation for the transfer of the Southern Bessarabia.

Early 20th century

The Kishinev pogrom took place in the capital of Bessarabia on April 6, 1903 after local newspapers published articles inciting the public to act against Jews; 47 or 49 Jews were killed, 92 severely wounded and 700 houses destroyed. The anti-Semitic newspaper Бессарабец (Bessarabetz, meaning "Bessarabian"), published by Pavel Krushevan, insinuated that a Russian boy was killed by local Jews. Another newspaper, Свет (Lat. Svet, meaning "World"), used the age-old blood libel against the Jews (alleging that the boy had been killed to use his blood in preparation of matzos).

After the 1905 Russian Revolution, a Romanian nationalist movement started to develop in Bessarabia. In the chaos brought by the Russian revolution of October 1917, a National Council (Sfatul Țării) was established in Bessarabia, with 120 members elected from Bessarabia by some political and professional organizations and 10 elected from Transnistria (the left bank of Dniester where Moldovans and Romanians accounted for less than a third and the majority of the population was Ukrainian. See Demographics of Transdniestria).

On January 14, 1918, during the disorderly retreat of two Russian divisions from the Romanian front, Chișinău was sacked.[citation needed] The Rumcherod Committee (Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Romanian Front, Black Sea Fleet and Odessa Military District) proclaimed itself the supreme power in Bessarabia. On 16 January, the Romanian Army began a full-scale invasion of Bessarabia; following several skirmishes with Moldavian and Bolshevik troops, the occupation of the whole region was completed in early March.

With Romanian troops holding Chișinău, on January 24, 1918, Sfatul Țării declared Bessarabia's independence as the Moldavian Democratic Republic.

Unification with Romania

The county councils of Bălți, Soroca and Orhei were the earliest to ask for unification with the Kingdom of Romania, and on April 9 [O.S. March 27] 1918, in the presence of the Romanian Army,[9] Sfatul Țării voted in favour of the union, with the following conditions:

- Sfatul Țării would undertake an agrarian reform, which would be accepted by the Romanian Government.

- Bessarabia would remain autonomous, with its own diet, Sfatul Țării, elected democratically

- Sfatul Țării would vote for local budgets, control the councils of the zemstva and cities, and appoint the local administration

- Conscription would be done on a territorial basis

- Local laws and the form of administration could be changed only with the approval of local representatives

- The rights of minorities had to be respected

- Two Bessarabian representatives would be part of the Romanian government

- Bessarabia would send to the Romanian Parliament a number of representatives equal to the proportion of its population

- All elections must involve a direct, equal, secret, and universal vote

- Freedom of speech and of belief must be guaranteed in the constitution

- All individuals who had committed felonies for political reasons during the revolution would be amnestied.

86 deputies voted in support, 3 voted against and 36 abstained.

The first condition, the agrarian reform, was debated and approved in November 1918. Sfatul Țării also decided to remove the other conditions and made unification with Romania unconditional.[10] This vote has been judged illegitimate, since there was no quorum: only 44 of the 125 members took part in it (all voted "for").[10] As of mid 1919, the population of Bessarabia was estimated at around 2 million.[11]

In the autumn of 1919, elections for the Romanian Constituent Assembly were held in Bessarabia; 90 deputies and 35 senators were chosen. On December 20, 1919, these men voted, along with the representatives of Romania's other regions, to ratify the unification acts that had been approved by Sfatul Țării and the National Congresses in Transylvania and Bukovina.

The union was recognized by France, United Kingdom, Italy, and Japan in the Treaty of Paris of 1920, which however never came into force, because Japan did not ratify it. The United States refused to sign the treaty on the grounds that Russia was not represented at the Conference.[12] Soviet Russia (and later, the USSR) did not recognize the union, and by 1924, after its demands for a regional plebiscite were declined by Romania for the second time, declared Bessarabia to be Soviet territory under foreign occupation.[13]

The US also considered Bessarabia a territory under Romanian occupation, rather than Romanian territory, despite existing political and economic relations between the US and Romania.[14]

Part of Romania

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

A Provisional Workers' & Peasants' Government of Bessarabia was founded on May 5, 1919, in exile at Odessa, by the Bolsheviks.

On May 11, 1919, the Bessarabian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as an autonomous part of Russian SFSR, but was abolished by the military forces of Poland and France in September 1919 (see Polish–Soviet War). After the victory of Bolshevist Russia in the Russian Civil War, the Ukrainian SSR was created in 1922, and in 1924 the Moldovan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established on a strip of Ukrainian land on the left bank of Dniester where Moldovans and Romanians accounted for less than a third and the relative majority of population was Ukrainian. (See Demographics of Moldovan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic).

World War II

The Soviet Union did not recognize incorporation of Bessarabia into Romania and throughout the entire interwar period engaged in attempts to undermine Romania and diplomatic disputes with the government in Bucharest over this territory.[13] The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed on August 23, 1939. By Article 4 of the secret Annex to the Treaty, Bessarabia fell within the Soviet interest zone.

In spring of 1940, Western Europe was overrun by Nazi Germany. With world attention focused on those events, on June 26, 1940, the USSR issued an ultimatum to Romania, demanding immediate cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. Romania was given four days to evacuate its troops and officials. The two provinces had an area of 51,000 km2 (20,000 sq mi), and were inhabited by about 3.75 million people, half of them Romanians, according to official Romanian sources. Two days later, Romania yielded and began evacuation. During the evacuation, from June 28 to July 3, groups of local Communists and Soviet sympathizers attacked the retreating forces, and civilians who chose to leave. Many members of the minorities (Jews, ethnic Ukrainians and others) joined in these attacks.[15] The Romanian Army was also attacked by the Soviet Army, which entered Bessarabia before the Romanian administration finished retreating. The casualties reported by the Romanian Army during those seven days consisted of 356 officers and 42,876 soldiers dead or missing.[16]

On August 2, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was established on most of the territory of Bessarabia, merged with the western parts of the former Moldavian ASSR. Bessarabia was divided between the Moldavian SSR (65% of the territory and 80% of the population) and the Ukrainian SSR. Bessarabia's northern and southern districts (now Budjak and parts of the Chernivtsi oblast) were allotted to Ukraine, while some territories (4,000 km2) on the left (eastern) bank of Dniester (present Transnistria), previously part of Ukraine, were allotted to Moldavia. Following the Soviet takeover, many Bessarabians, who were accused of supporting the deposed Romanian administration, were executed or deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan.

Between September and November 1940, the ethnic Germans of Bessarabia were offered resettlement to Germany, following a German-Soviet agreement. Fearing Soviet oppression, almost all Germans (93,000) agreed. Most of them were resettled to the newly annexed Polish territories.

On June 22, 1941 the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union commenced with Operation Barbarossa. Between June 22 and July 26, 1941, Romanian troops with the help of Wehrmacht recovered Bessarabia and northern Bukovina. The Soviets employed scorched earth tactics during their forced retreat from Bessarabia, destroying the infrastructure and transporting movable goods to Russia by railway. At the end of July, after a year of Soviet rule, the region was once again under Romanian control.

As the military operation was still in progress, there were cases of Romanian troops "taking revenge" on Jews in Bessarabia, in the form of pogroms on civilians and murder of Jewish POWs, resulting in several thousand dead. The supposed cause for murdering Jews was that in 1940 some Jews welcomed the Soviet takeover as liberation. At the same time the notorious SS Einsatzgruppe D, operating in the area of the German 11th Army, committed summary executions of Jews under the pretext that they were spies, saboteurs, Communists, or under no pretext whatsoever.

The political solution of the "Jewish Question" was apparently seen by the Romanian dictator Marshal Ion Antonescu more in expulsion rather than extermination. That portion of the Jewish population of Bessarabia and Bukovina which did not flee before the retreat of the Soviet troops (147,000) was initially gathered into ghettos or Nazi concentration camps, and then deported during 1941–1942 in death marches into Romanian-occupied Transnistria, where the "Final Solution" was applied.[17]

After three years of relative peace, the German-Soviet front returned in 1944 to the land border on the Dniester. On August 20, 1944, a c. 3,400,000-strong Red Army began a major summer offensive codenamed Jassy-Kishinev Operation. The Soviet armies overran Bessarabia in a two-pronged offensive within five days. In pocket battles at Chișinău and Sărata the German 6th Army of c. 650,000 men, newly reformed after the Battle of Stalingrad, was obliterated. Simultaneously with the success of the Russian attack, Romania broke the military alliance with the Axis and changed sides. On August 23, 1944, Marshal Ion Antonescu was arrested by King Michael, and later handed over to the Soviets.

Part of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union regained the region in 1944, and the Red Army occupied Romania. By 1947, the Soviets had imposed a communist government in Bucharest, which was friendly and obedient towards Moscow. The Soviet occupation of Romania lasted until 1958. The Romanian communist regime did not openly raise the matter of Bessarabia or Northern Bukovina in its diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union.

Between 1969 and 1971, a clandestine National Patriotic Front was established by several young intellectuals in Chișinău, totaling over 100 members, vowing to fight for the establishment of a Moldavian Democratic Republic, its secession from the Soviet Union and union with Romania.

In December 1971, following an informative note from Ion Stănescu, the President of the Council of State Security of the Romanian Socialist Republic, to Yuri Andropov, the chief of KGB, three of the leaders of the National Patriotic Front, Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgar, Gheorghe Ghimpu and Valeriu Graur, as well as a fourth person, Alexandru Soltoianu, the leader of a similar clandestine movement in northern Bukovina (Bucovina), were arrested and later sentenced to long prison terms.[18]

Rise of independent Moldova

With the weakening of the Soviet Union, in February 1988, the first non-sanctioned demonstrations were held in Chișinău. At first pro-Perestroika, they soon turned anti-government and demanded official status for the Romanian (Moldavian) language instead of the Russian language. On August 31, 1989, following a 600,000-strong demonstration in Chișinău four days earlier, Romanian (Moldavian) became the official language of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. However, this was not implemented for many years. In 1990, the first free elections were held for Parliament, with the opposition Popular Front winning them. A government led by Mircea Druc, one of the leaders of the Popular Front, was formed. The Moldavian SSR became SSR Moldova, and later the Republic of Moldova. The Republic of Moldova became independent on August 31, 1991; it took over unchanged the boundaries of the Moldavian SSR.

Population

According to Bessarabian historian Ștefan Ciobanu and Moldovan philologist Viorica Răileanu, in 1810 the percentage of the Romanian (Moldavian) population was approximately 95%.[19][20] During the 19th century, as a result of the Russian policy of colonization and Russification,[21] the Romanian population decreased to (depending on data sources) 47.6% (in 1897), 52% or 75% for 1900 (Krusevan), 53.9% (1907), 70% (1912, Laskov), or 65–67% (1918, J. Kaba).[22]

The Russian Census of 1817, which recorded 96,526 families and 482,630 inhabitants, did not register ethnic data except for recent refugees (primarily Bulgarians) and certain ethno-social categories (Jews, Armenians and Greeks).[23] In the 20th century, Romanian historian Ion Nistor extrapolated the numbers for the ethnic groups,[23] providing the following estimates: 83,848 Romanian families (86%), 6,000 Ruthenian families (6.5%), 3,826 Jewish families (4.2%), 1,200 Lipovan families (1.5%), 640 Greek families (0.7%), 530 Armenian families (0.6%), 482 Bulgarian and Gagauz families (0.5%).[24] An 1818 statistic of three counties in southern Bessarabia (Akkerman, Izmail and Bender) that had witnessed strong emigration of the Muslim population and immigration from other regions, including Ottoman lands south of the Danube, recorded the following percentages: 48.64% Moldavians, 7.07% Russians, 15.65% Ukrainians, 17.02% Bulgarians and 11.62% others, amounting to a total population of 113,835.[25]

According to an administrative census made in 1843–1844 at the request of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the following proportions were recorded, in a total of 692,777 inhabitants: 59.4% Moldavians, 17.2% Ukrainians, 9.3% Bulgarians, 7.1% Jews and 2.2% Russians. It should be noted that, in the case of some urban centres, figures were not reported for all ethnic groups. Furthermore, the size of the total populations differs from other official reports of the same period, which put the population of Bessarabia at 774,492 or 793,103.[26]

Church records gathered around 1850–1855 put the total population at 841,523, with the following composition: 51.4% Moldavians, 4.2% Russians, 21.3% Ukrainians, 10% Bulgarians, 7.2% Jews and 5.7% others. On the other hand, official data for 1855 record a total population of 980,031, excluding the population on the territory under the authority of the Special Administration of the town of Izmail.[27]

According to Ion Nistor, the population of Bessarabia in 1856 was composed of 736,000 Romanians (74%), 119,000 Ukrainians (12%), 79,000 Jews (8%), 47,000 Bulgarians and Gagauz (5%), 24,000 Germans (2.4%), 11,000 Romani (1.1%), 6,000 Russians (0.6%), adding to a total of 990,274 inhabitants.[24]

Russian data, 1889 (Total: 1,628,867 inhabitants)

Russian Census, 1897 (Total 1,935,412 inhabitants).[28] By language:

- 920,919 Moldavians/Romanians (47.6%)

- 379,698 Ukrainians (19.6%)

- 228,168 Jews (11.8%)

- 155,774 Russians (8%)

- 103,225 Bulgarians (5.3%)

- 60,026 Germans (3.1%)

- 55,790 Turks (Gagauzes) (2.9%)

Some scholars, however, believed in regard to the 1897 census that "[...] the census enumerator generally has instructions to count everyone who understands the state language as being of that nationality, no matter what his everyday speech may be.", thus a number of Moldavians (Romanians) might have been registered as Russians.[29]

According to N. Durnovo, the population of Bessarabia in 1900 was (Total: 1,935,000 inhabitants):[30]

| County | Romanians | Ukrainians and Russians |

Jews | Bulgarians and Gagauz |

Germans, Greeks, Armenians, others |

Total inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotin County | 89,000 | 161,000 | 54,000 | 3,000 | 307,000 | |

| Soroca County | 156,000 | 28,000 | 31,000 | 4,000 | 219,000 | |

| Bălți County | 154,000 | 27,000 | 17,000 | 14,000 | 212,000 | |

| Orhei County | 176,000 | 10,000 | 26,000 | 1,000 | 213,000 | |

| Lăpușna County | 198,000 | 19,000 | 53,000 | 10,000 | 280,000 | |

| Tighina County | 103,000 | 32,000 | 16,000 | 36,000 | 8,000 | 195,000 |

| Cahul and Ismail1 | 109,000 | 53,000 | 11,000 | 27,000 | 44,000 | 244,000 |

| Cetatea Albă County | 106,000 | 48,000 | 11,000 | 52,500 | 47,500 | 265,000 |

| Total | 1,092,000 | 378,000 | 219,000 | 247,000 | 1,935,000 | |

| % | 56.5% | 19.5% | 11.5% | 12.5% | 100% | |

Notes: 1 The two counties were merged.

Romanian Census, 1930 (Total: 2,864,662 inhabitants)

| County | Romanians | Ukrainians | Russians1 | Jews | Bulgarians | Gagauz | Germans | others2 | Total inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hotin County | 137,348 | 163,267 | 53,453 | 35,985 | 26 | 2 | 323 | 2,026 | 392,430 |

| Soroca County | 232,720 | 26,039 | 25,736 | 29,191 | 69 | 13 | 417 | 2,183 | 316,368 |

| Bălți County | 270,942 | 29,288 | 46,569 | 31,695 | 66 | 8 | 1,623 | 6,530 | 386,721 |

| Orhei County | 243,936 | 2,469 | 10,746 | 18,999 | 87 | 1 | 154 | 2,890 | 279,282 |

| Lăpușna County | 326,455 | 2,732 | 29,770 | 50,013 | 712 | 37 | 2,823 | 7,079 | 419,621 |

| Tighina County | 163,673 | 9,047 | 44,989 | 16,845 | 19,599 | 39,345 | 10,524 | 2,570 | 306,592 |

| Cahul County | 100,714 | 619 | 14,740 | 4,434 | 28,565 | 35,299 | 8,644 | 3,948 | 196,963 |

| Ismail County | 72,020 | 10,655 | 66,987 | 6,306 | 43,375 | 15,591 | 983 | 9,592 | 225,509 |

| Cetatea Albă County | 62,949 | 70,095 | 58,922 | 11,390 | 71,227 | 7,876 | 55,598 | 3,119 | 341,176 |

| Total | 1,610,757 | 314,211 | 351,912 | 204,858 | 163,726 | 98,172 | 81,089 | 39,937 | 2,864,662 |

| % | 56.23% | 10.97% | 12.28% | 7.15% | 5.72% | 3.43% | 2.83% | 1.39% | 100% |

Notes: 1 Includes Lipovans. 2 Poles, Armenians, Albanians, Greeks, Gypsies, etc. and non-declared

When?: Total: 2,995,821

- Romanians 1,735,000

- Ukrainians 315,000

- Russians 352,000

- Jews 210,000

- Bulgarians 164,000

- Gagauz 99,000

- Germans 82,000

- others ?

Data of the Romanian census 1939 was not completely processed before the Soviet occupation of Bessarabia. Estimates of the total population at 3.2 million.

Soviet census for the Moldavian SSR (including Transnistria; northern and southern Bessarabia - part of Ukraine - not included), 1979: 63.9% identified themselves as Moldovans and 0.04% as Romanians.

Soviet census (Moldavian SSR), 1989: 64.5% Moldovans and 0.06% Romanians.

Moldovan census, 2004 (not including Transnistria): 75.81% Moldovans and 2.17% Romanians.

Economy

- 1911: There were 165 loan societies, 117 savings banks, forty three professional savings and loan societies, and eight Zemstvo loan offices; all these had total assets of about 10,000,000 rubles. There were also eighty nine government savings banks, with deposits of about 9,000,000 rubles.

- 1918: There was only 1,057 km (657 mi) of railway; the main lines converged on Russia and were broad gauge. Rolling stock and right of way were in bad shape. There were about 400 locomotives, with only about one hundred fit for use. There were 290 passenger coaches and thirty three more out for repair. Finally, out of 4530 freight cars and 187 tank cars, only 1389 and 103 were usable. The Romanians reduced the gauge to a standard 1,440 mm (56.5 in), so that cars could be run to the rest of Europe. Also, there were only a few inefficient boat bridges. Romanian highway engineers decided to build ten bridges: Cuzlău, Țuțora, Lipcani, Șerpenița, Ștefănești–Brăniște, Cahul-Oancea, Bădărăi-Moara Domnească, Sărata, Bumbala-Leova, Badragi and Fălciu (Fălciu is a locality in Romania. Its correspondent in Bessarabia is Cantemir.) Of these, only four were ever finished: Cuzlău, Fălciu, Lipcani and Sărata.

See also

References

- ^ Clark, Charles Upson (1927). Bessarabia. New York City: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ Coman, Marian (2011). "Basarabia – Inventarea cartografică a unei regiuni". Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie. XXIX. Institutul de Istorie Nicolae Iorga: 183–215. ISSN 1222-4766.

- ^ Descrierea Basarabiei: teritoriul dintre Prut și Nistru în evoluție istorică (din primele secole ale mileniului II până la sfîrșitul secolului al XX-lea). Cartier. 2011. pp. 414–. ISBN 978-9975-79-704-7.

- ^ Template:RoHotia C. Matei, "Enciplopedia de istorie" ("History encyclopedia"), Meronia, Bucharest, 2006, ISBN 978-973-7839-03-9, pag. 290

- ^ Mihai Bărbulescu, Dennis Diletant, Keith Hitchins, Șerban Papacostea, Pompiliu Teodor, "Istoria României", Corint, Bucharest, 2007, ISBN 978-973-135-031-8, pag. 77

- ^ Чеботаренко, Г.Ф. Материалы к археологической карте памятников VІІІ-Х вв. южной части Пруто-Днестровского междуречья//Далекое прошлое Молдавии, Кишинев, 1969, с. 224–230

- ^ Prothero, GW, ed. (1920). Bessarabia. Peace handbooks. London: H.M. Stationery Office. pp. 12, 15–16.

- ^ Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 31.

- ^ Cristina Petrescu, "Contrasting/Conflicting Identities:Bessarabians, Romanians, Moldovans" in Nation-Building and Contested Identities, Polirom, 2001, pg. 156, also footnote №23 on page 169

- ^ a b Charles King, "The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture", Hoover Press, 2000, pg. 35

- ^ Kaba, John (1919). Politico-economic Review of Basarabia. United States: American Relief Administration. p. 8.

- ^ Wayne S Vucinich, Bessarabia In: Collier's Encyclopedia (Crowell Collier and MacMillan Inc., 1967) vol. 4, p. 103

- ^ a b C. Petrescu, footnote №26 on page 170

- ^ Moldova: a Romanian province under Russian rule p. 131

- ^ Nagy-Talavera, Nicolas M. (1970). Green Shirts and Others: a History of Fascism in Hungary and Romania. p. 305.

- ^ Paul Goma (2006). Săptămâna Roșie. p. 206.

- ^ "Constructing Interethnic Conflict and Cooperation: Why Some People Harmed Jews and Others Helped Them during the Holocaust in Romania Diana Dumitru". World Politics. 63 (1): 1–42. January 2011. Retrieved 2014-10-19.

- ^ "Political Repressions in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic after 1956: Towards a Typology Based on KGB files Igor Casu". Dystopia. I (1–2): 89–127. 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-19.

- ^ Ciobanu, Ștefan (1923). Cultura românească în Basarabia sub stăpânirea rusă. Chișinău: Editura Asociației Uniunea Culturală Bisericească. p. 20.

- ^ The Memory of (Im)Proper Names from Basarabia

- ^ Marcel Mitrasca (2007). Moldova: A Romanian Province Under Russian Rule : Diplomatic History from the Archives of the Great Powers. Algora Publishing. pp. 20–. ISBN 978-0-87586-184-5.

- ^ Cenuses in Bessarabia

- ^ a b Poștarencu, Dinu (2009). Contribuții la istoria modernă a Basarabiei. II. Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-9975-78-735-2.

- ^ a b Ion Nistor, Istoria Basarabiei, edit. Humanitas, București, 1991

- ^ Poștarencu, Dinu (2009). Contribuții la istoria modernă a Basarabiei. II. Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. p. 30. ISBN 978-9975-78-735-2.

- ^ Poștarencu, Dinu (2009). Contribuții la istoria modernă a Basarabiei. II. Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-9975-78-735-2.

- ^ Poștarencu, Dinu (2009). Contribuții la istoria modernă a Basarabiei. II. Chișinău: Tipografia Centrală. p. 40. ISBN 978-9975-78-735-2.

- ^ Results of the 1897 Russian Census at demoscope.ru Archived 2016-05-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charles Upson Clark, Bessarabia. Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea: "These figures were based on estimates of the population of Bessarabia as consisting 70% of Moldavians, 14% Ukrainians, 12% Jews, 6% Russians, 3% Bulgarians, 3% Germans, 2% Gagautzi (Turks of Christian religion), and 1% Greeks and Armenians. This appears to be a fairly accurate guess; the official Russian figures, which the Moldavians considered as inaccurate and padded, set the Moldavian proportion considerably lower, as about one-half. Such figures are misleading in all European countries of mixed nationalities, since the census enumerator generally has instructions to count everyone who understands the state language as being of that nationality, no matter what his everyday speech may be."

- ^ cf. Nistor, pp. 212–213

- Thilemann, Alfred. Steppenwind: Erzahlungen aus dem Leben der Bessarabien deutschen (The Wind from the Steppe: Stories of the Life of the Bessarabian Germans). Stuttgart, West Germany: Heimatmuseum der Deutschen aus Bessarabien e. V., 1982.

External links

- Charles Upson Clark. 1927. "Bessarabia: Russia and Roumania on the Black Sea". (An electronic version of the book).

- George F. Jewsbury (1976). The Russian Annexation of Bessarabia, 1774–1828: A Study of Imperial Expansion. East European Quarterly. ISBN 978-0-914710-09-7.

- Ioan Scurtu (2003). Istoria Basarabiei de la începuturi până în 2003. Editura Institutului Cultural Român.

- Jews in Bessarabia on the eve of WWII

- Massacres, deportations & death marches from Bessarabia, from July 1941

- Bessarabia – Homeland of a German minority

- Igor Casu, (2000) "Politica națională" în Moldova Sovietică, 1944–1989, Chisinau, 214 p.

- Игор Кашу, (2014) У истоков советизации Бессарабии. Выявление "классового врага", конфискация имущества и трудовая мобилизация, 1940–1941. Сборник документов. Chisinau,CARTIER 458 p.

- Андрей Кушко, Виктор Таки, Олег Гром (2012) Бессарабия в составе Российской империи (1812—1917). Москва, Новое Литературное обозрение, 400 с.

- Igor Casu, (2014) Dusmanul de clasa. Represiuni politice, violenta si rezistenta in R(A)SS Moldoveneasca, 1924–1956, Chisinau, CARTIER, 394p.