Cham script

| Cham | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | 8th century–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Cham |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cham (358), Cham |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cham |

| U+AA00–U+AA5F | |

The Cham alphabet is an abugida used to write Cham, an Austronesian language spoken by some 230,000 Chams in Vietnam and Cambodia. It is written horizontally left to right, as in English.

History

The Cham script is a descendant of the Brahmi script of India. Cham was one of the first scripts to develop from a South Indian Brahmi script called the Grantha alphabet some time around 200 CE. It came to Southeast Asia as part of the expansion of Hinduism and Buddhism. Hindu stone temples of the Champa civilization contain both Sanskrit and Chamic language stone inscriptions.[1] The earliest inscriptions in Vietnam are found in Mỹ Sơn, a temple complex dated to around 400 CE. The oldest inscription is written in faulty Sanskrit. After this, inscriptions alternate between Sanskrit and the Cham language of the times.[2]

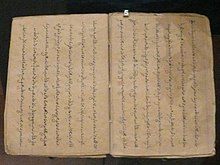

Cham kings studied classical Indian texts such as the Dharmaśāstra and inscriptions make reference to Sanskrit literature. Eventually, while the Cham and Sanskrit languages influenced one another, Cham culture assimilated Hinduism, and Chams were eventually able adequately express the Hindu religion in their own language.[2] By the 8th century, the Cham script had outgrown Sanskrit and the Cham language was in full use.[3] Most preserved manuscripts focus on religious rituals, epic battles and poems, and myths.[2]

Modern Chamic languages have the Southeast Asian areal features of monosyllabicity, tonality, and glottalized consonants. However, they had reached the Southeast Asia mainland disyllabic and non-tonal. The script needed to be altered to meet these changes.[1]

The Cham now live in two groups: the Western Cham of Cambodia and the Eastern Cham (Phan Rang Cham) of Vietnam. For the first millennium AD, the Chamic languages were a dialect chain along the Vietnam coast. The breakup of this chain into distinct languages occurred once the Vietnamese pushed south, causing most Cham to move back into the highlands while some like Phan Rang Cham became a part of the lowland society ruled by the Vietnamese. The division of Cham into Western and Phan Rang Cham immediately followed the Vietnamese overthrow of the last Cham polity.[1] Each uses a distinct variety of the script, although the former are mostly Muslim[4] and now prefer to use the Arabic alphabet. The latter are mostly Hindu and still use the Cham script. During French colonial times, both groups had to use the Latin alphabet.

Usage

The script is highly valued in Cham culture, but this does not mean that many people are learning it. There have been efforts to simplify the spelling and to promote learning the script, but these have met with limited success.[5] Traditionally, boys learned the script around the age of twelve when they were old and strong enough to tend to the water buffalo. However, women and girls did not typically learn to read.[3] The traditional Indic Cham script is still known and used by Vietnam's Eastern Cham but no longer by the Western Cham.[6]

Structure

As an abugida, Cham writes individual consonants supplemented by obligatory vowel diacritics tacked onto the consonant.

Most consonant letters, such as [b], [t], or [p], includes an inherent vowel [a] which does not need to be written. The nasal stops, [m], [n], [ɲ], and [ŋ] (the latter two transliterated nh and ng in the Latin alphabet) are exceptions, and have an inherent vowel [ɨ] (transliterated eu). A diacritic called kai, which does not occur with the other consonants, is added below a nasal consonant to write the [a] vowel.[3]

Cham words contain vowel and consonant-vowel (V and CV) syllables, apart from the last, which may also be CVC. There are a few characters for final consonants in the Cham script; other consonants merely extend a longer tail on the right side to indicate the absence of a final vowel.[3]

Unicode

Cham script was added to the Unicode Standard in April, 2008 with the release of version 5.1.

The Unicode block for Cham is U+AA00–U+AA5F:

| Cham[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+AA0x | ꨀ | ꨁ | ꨂ | ꨃ | ꨄ | ꨅ | ꨆ | ꨇ | ꨈ | ꨉ | ꨊ | ꨋ | ꨌ | ꨍ | ꨎ | ꨏ |

| U+AA1x | ꨐ | ꨑ | ꨒ | ꨓ | ꨔ | ꨕ | ꨖ | ꨗ | ꨘ | ꨙ | ꨚ | ꨛ | ꨜ | ꨝ | ꨞ | ꨟ |

| U+AA2x | ꨠ | ꨡ | ꨢ | ꨣ | ꨤ | ꨥ | ꨦ | ꨧ | ꨨ | ꨩ | ꨪ | ꨫ | ꨬ | ꨭ | ꨮ | ꨯ |

| U+AA3x | ꨰ | ꨱ | ꨲ | ꨳ | ꨴ | ꨵ | ꨶ | |||||||||

| U+AA4x | ꩀ | ꩁ | ꩂ | ꩃ | ꩄ | ꩅ | ꩆ | ꩇ | ꩈ | ꩉ | ꩊ | ꩋ | ꩌ | ꩍ | ||

| U+AA5x | ꩐ | ꩑ | ꩒ | ꩓ | ꩔ | ꩕ | ꩖ | ꩗ | ꩘ | ꩙ | ꩜ | ꩝ | ꩞ | ꩟ | ||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ a b c Thurgood, Graham. From Ancient Cham to Modern Dialects: Two Thousand Years of Language Contact and Change. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1999.

- ^ a b c Claude, Jacques. “The Use of Sanskrit in the Khmer and Cham Inscriptions.” In Sanskrit Outside India (Vol. 7, pp. 5-12). Leiden: Panels of the VIIth World Sanskrit Conference. 1991.

- ^ a b c d Blood, Doris E. "The Script as a Cohesive Factor in Cham Society". In Notes from Indochina on ethnic minority cultures. Ed. Marilyn Gregerson. 1980 p35-44.

- ^ Trankell & Ovesen 2004

- ^ Blood 1980a,b, 2008, Brunelle 2008.

- ^ Akbar Husain, Wim Swann Horizons of Spiritual Psychology 2009 - Page 28 "The traditional Cham script, based on an Indian script, is still known and used by the Eastern Cham in Vietnam, but it has been lost by the Western Cham. The Cham language is also non-tonal. Words may contain one, two, or three syllables."

Literature

- Etienne Aymonier, Antoine Cabaton (1906). Dictionnaire čam-français. Vol. Volume 7 of Publications de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. E. Leroux. Retrieved 2011-05-15.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Blood, Doris (1980a). Cham literacy: the struggle between old and new (a case study). Notes on Literacy 12, 6-9.

- Blood, Doris (1980b). The script as a cohesive factor in Cham society. In Notes from Indochina, Marilyn Gregersen and Dorothy Thomas (eds.), 35-44. Dallas: International Museum of Cultures.

- Blood, Doris E. 2008. The ascendancy of the Cham script: how a literacy workshop became the catalyst. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 192:45-56.

- Brunell, Marc. 2008. Diglossia, Bilingualism, and the Revitalization of Written Eastern Cham. Language Documentation and Conservation 2.1: 28-46. (Web based journal)

- Moussay, Gerard (1971). Dictionnaire Cam-Vietnamien-Français. Phan Rang: Centre Culturel Cam.

- Trankell, Ing-Britt and Jan Ovesen (2004). Muslim minorities in Cambodia. NIASnytt 4, 22-24. (Also on Web)

External links

![]() Media related to Cham script at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cham script at Wikimedia Commons