Civil Cooperation Bureau

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

The South African Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB) was a government-sponsored death squad[1] during the apartheid era that operated under the authority of Defence Minister General Magnus Malan. The Truth and Reconciliation Committee pronounced the CCB guilty of numerous killings, and suspected more killings.[2][3][4][5]

Forerunners and contemporaries

When South African newspapers first revealed its existence in the late 1980s, the CCB appeared to be a unique and unorthodox security operation: its members wore civilian clothing; it operated within the borders of the country; it used private companies as fronts; and it mostly targeted civilians. However, as the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) discovered a decade later, the CCB's methods were neither new nor unique. Instead, they had evolved from precedents set in the 1960s and 70s by Eschel Rhoodie's Department of Information (see Muldergate Scandal[6]), the Bureau of State Security (B.O.S.S.)[7] and Project Barnacle (a top-secret project to eliminate SWAPO detainees and other "dangerous" operators).[8]

From information given to the TRC by former agents seeking amnesty for crimes committed during the apartheid era, it became clear that there were many other covert operations similar to the CCB, which Nelson Mandela would label the Third Force. These operations included Wouter Basson's 7 Medical Battalion Group,[9] the Askaris, Witdoeke, Experimental Group Program (also called "Clandestine Cooperation Bureau") and C1/C10 or Vlakplaas.

Besides these, there were also political front organizations like the International Freedom Foundation, Marthinus van Schalkwyk's Jeugkrag (Youth for South Africa),[10] and Russel Crystal's National Student Federation[11] which would demonstrate that while the tactics of the South African government varied, the logic remained the same: Total onslaught demanded a total strategy.[12]

Establishment

Inaugurated in 1986 with the approval of Minister of Defense General Magnus Malan[13][14] and Chief of SADF General Jannie Geldenhuys, the CCB became fully functional by 1988. As a reformulation of Project Barnacle, the nature of its operations were disguised, and it disassociated itself from all other Special Forces and DMI (Directorate Military Intelligence) structures. The CCB formed the third arm of the Third Force, alongside Vlakplaas C1 and the Special Tasks projects.[15]

In his 1997 submission to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission,[16] General Malan described the CCB as follows:

"15.1 Let me now deal with the matter of the CCB. The CCB-organization as a component of Special Forces was approved in principle by me. Special Forces was an integral and supportive part of the South African Defence Force. The role envisaged for the CCB was the infiltration and penetration of the enemy, the gathering of information and the disruption of the enemy. The CCB was approved as an organization consisting of ten divisions, or as expressed in military jargon, regions. Eight of these divisions or regions were intended to refer to geographical areas. The area of one of these regions, Region Six, referred to the Republic of South Africa. The fact that the organization in Region Six was activated, came to my knowledge for the first time in November 1989. The CCB provided the South African Defence Force with good covert capabilities. 15.2 During my term of office as Head of the South African Defence Force and as Minister of Defence instructions to members of the South African Defence Force were clear: destroy the terrorists, their bases and their capabilities. This was also government policy. As a professional soldier, I issued orders and later as Minister of Defence I authorised orders which led to the death of innocent civilians in cross-fire. I sincerely regret the civilian casualties, but unfortunately this is part of the ugly reality of war. However, I never issued an order or authorised an order for the assassination of anybody, nor was I ever approached for such authorization by any member of the South African Defence Force. The killing of political opponents of the government, such as the slaying of Dr Webster, never formed part of the brief of the South African Defence Force."

Reports about the CCB were first published in 1990 by the now-defunct weekly Vrye Weekblad, and more detailed information emerged later in the 1990s at a number of TRC amnesty hearings. General Joep Joubert, in his testimony before the TRC, revealed that the CCB was a long-term special forces project in the South African Defence Force. It had evolved from the 'offensive defence' philosophy prevalent in P.W. Botha's security establishment.[17]

Nominally a civilian organisation that could be plausibly disowned by the apartheid government, the CCB drew its operatives from the SADF itself or the South African Police. According to Joubert, many operatives did not know that they were members of an entity called the CCB.[18]

In the wake of the National Party government's Harms Commission, whose proceedings were considered seriously flawed by analysts and the official opposition, the CCB was disbanded in August 1990.[19] Some members were transferred to other security organs.[20] No prosecutions resulted.

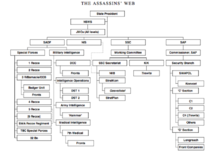

Structure

The CCB consisted of four groups with different functions:[21] an executive, a management board, two staff functions, eight operational sections known as regions, and an ad hoc collection of contractors. The overall size of the CCB never exceeded 250-300 full-time personnel.[22]

Executive

There is much dispute about what senior military officers knew when. However it is common cause that the CCB was a unit of special forces at first controlled by the General Officer Commanding Special Forces, Major-General Eddie Webb[23]: 53 [24] who reported to the Chief of the SADF.

Management board

The CCB operated as a civilian entity, so it had a chairman of the board and a group of 'directors'. The GOC Special Forces – Major General Joep Joubert (1985–89) followed by Major General Eddie Webb from the beginning of 1989 - was the chairman. The rest of the board included Joe Verster (managing director), Dawid Fourie (deputy MD), WJ Basson, Theuns Kruger, and Lafras Luitingh.

Staff functions

Although there is consistent evidence that the CCB had two staff functions[23]: 53 it is not clear what the names of these groups were and whether these remained the same over the life of the CCB. Region 9, is sometimes referred to as Intelligence or Psychological Warfare and elsewhere as Logistics. Region 10 is known as Finance and Administration or simply Administration.[25]

Operational sections

Each region had an area manager and its own co-ordinator who reported to the managing director.

- Region 1: Botswana - regional manager up to 1988 was Commandant Charl Naudé and thereafter Dawid Fourie, while Christoffel Nel handled the intelligence function.

- Region 2: Mozambique and Swaziland - the manager was Commandant Corrie Meerholtz until the end of 1988. He was replaced by the operational co-ordinator, Captain Pieter Botes. while the intelligence function was performed by Peter Stanton, one of the few remaining ex-Rhodesians from the D40 and Barnacle eras.

- Region 3: Lesotho - Fourie was also the manager in region 3.

- Region 4: Angola, Zambia and Tanzania - Dawid Fourie was also responsible, taking it over in 1988 from Meerholtz. Christoffel Nel handled the intelligence function while Ian Strange was also involved in this region.

- Region 5: International/Europe – Johan Niemoller appears to have been coordinator. In 1987, he was suddenly withdrawn following the arrest of a number of individuals living in England on charges of plotting to kill ANC leaders. Eeben Barlow, the founder of the private military company, Executive Outcomes, then took command of Region 5.[26]

- Region 6: South Africa - formed on 1 June 1988; Staal Burger was regional manager; operatives included 'Slang' Van Zyl, Chappies Maree and Calla Botha. The TRC later receives eight amnesty applications related to four operations: 1) the attempted killing of Abdullah Omar, 2) the planned killing of Gavin Evans, 3) bombing of the Early Learning Centre in Athlone Cape Town on 31 August 1989, 4) the harassment of Archbishop Desmond Tutu in Cape Town in 1989.

- Region 7: Zimbabwe - Various CCB members co-ordinated this region including WJ Basson and Lafras Luitingh. Others involved in sub-management were Ferdi Barnard (for a brief period) and Alan Trowsdale. Kevin Woods and three members of a CCB cell, Barry Bawden, Philip Conjwayo and Michael Smith conducted a Bulawayo bombing action.

- Region 8: South West Africa - headed by Roelf van Heerden.

Unknown region: Operated by ex S.A.D.F. members. Some names were: Micks McCloud (aka:Ausie)and Schalk Van Der Merwe (aka: William Reid, Morise Morris, Reson)

Blue plans and red plans

Operatives were required to have a 'blue plan'. This referred to a front operation (mostly a business) funded by the CCB. Slang Van Zyl, for instance, started a private investigation business while Chappies Maree ran an electronic goods export company called Lema. Operatives were allowed to keep the proceeds of their activities.[27] Proceeds from all blue plan activities vastly exceeded the funding CCB received from the state. A large private sector was created, which employing tens of thousands of people. Former security officers not in the CCB ran these companies alongside CCB officers.[22] In the December 1993 Goldstone Commission, the task group found that ex CCB members were involved in various illegal activities including gun and drug smuggling

Red plans, on the other hand, detailed the activities they would undertake against the enemy. Operations could be of a criminal nature as long as they had prior approval from the CCB bureaucracy. These mostly began with a feasibility study. If the report showed merit it was verified, then reviewed by a panel of five: the operative, the manager or handler, the coordinator, the managing director and in the case of violent operations, the chairman. Where loss of life was anticipated the chairman was required to obtain approval from the Chief of the Army or the Chief of Staff.[27]

The 'red plan' targeted victims and detailed action to be taken against them. The scenario, as described by Max Coleman in A Crime Against Humanity: Analysing the Repression of the Apartheid State, was as follows:

Step 1: A person or a target would be identified as an enemy of the State. A cell member would then be instructed to monitor the 'target'.

Step 2: A project - i.e. the elimination of a target would be registered with the co-ordinator. The co-ordinator would then have the project authorised by the regional manager and the managing director.

Step 3: The CCB member would then do a reconnaissance to study the target's movements with a view to eliminating him or her.

Step 4: The operative would propose the most practical method to the managing director. If the director felt this method was efficient, he would sign the proposal at what was called an 'in-house' meeting. There adjustments could be made to the plan before it was approved. The budget would be considered and finance would be made available for the project. The finance would come from the budget the Defence Force allocated to CCB activities. Indications are that money was always paid in cash.

Step 5: The co-ordinator would be requested to make available the necessary arms and ammunition such as limpet mines, poison and/or live ammunition or other logistical support such as transport, etc.

Step 6: The project would be carried out and the target would be eliminated. To do this the cell member could engage the assistance of what were termed 'unconscious members'. These were essentially underworld criminals who would, for money, kill as instructed. These 'unconscious' members were never told of the motive or the SADF connection - a false motive was usually supplied.[28]

Known and suspected operations

To date there is no published record covering all operations conducted during the CCB's five-year existence. It is estimated[who?] that 85–100 active operations were conducted, including:

- Alleged harassment of

- Afrikaner dissident and Vrye Weekblad editor Max du Preez by pointing an RPG7 at him while forcing him to consume a large amount of mampoer or moonshine[29]

- actor and playwright Hannes Muller for his role in Somewhere on the Border, a play banned by the authorities for its criticism of the South African Border War[30]

- Alleged shooting of Danger Nyoni – 12 December 1986

- Attempted contamination of drinking water in a Namibian refugee camp, by introducing cholera bacterium into it, in an effort to disrupt that country's independence from South Africa[31] – August 1989[32]

- Attempted assault on UN Special Representative, Martti Ahtisaari, in Namibia – 1989. According to a hearing in September 2000 of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, two CCB operatives (Kobus le Roux and Ferdinand Barnard) were tasked not to kill Ahtisaari, but to give him "a good hiding". To carry out the assault, Barnard had planned to use the grip handle of a metal saw as a knuckleduster. In the event, Ahtisaari did not attend the meeting at the Keetmanshoop Hotel, where Le Roux and Barnard lay in wait for him, and thus escaped injury.[33]

- Attempted killing of

- Jeremy Brickhill in Harare – 13 October 1987[34]

- Reverend Frank Chikane by poisoning – 1989

- Father Michael Lapsley,[35] who lost both hands and an eye in a letter bomb attack in Harare – 28 April 1990

- Godfrey Motsepe in Brussels – 4 February 1988

- January Masilela — known as "Che O'Gara", his Umkhonto we Sizwe nom-de-guerre.[36] On 30 September 2002, Masilela wrote to the South African Special Forces League conferring the Defence Minister's recognition of the SFL as being "legally representative of the interests of military veterans."

- Dullah Omar[37] – 1989

- Anton Roskam – incorrectly spelled Rosskam in TRC transcripts, received threatening letters, car was set alight[38]

- Albie Sachs – by bombing in Maputo in which he lost an arm and sight in one eye while in a car borrowed from Indres Naidoo thought to have been[39] the actual target – 7 April 1988

- Bombing of a Western Cape kindergarten – the Early Learning Centre – on the evening of 31 August 1989[40]

- Harassment of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, by hanging a baboon foetus in the garden of his Cape Town home in 1989 in the hope that it would bewitch him[41]

- Killing of

- Tsitsi Chiliza, the wife of an ANC member killed in an operation targeted at Jacob Zuma – 11 May 1987

- Christopher[who?], by injection on the way to Zeerust in a vehicle in which operatives Gary Strout and Trevor Floyd were traveling[2]

- SWAPO activist Anton Lubowski[42]

- Jacob 'Boy' Molekwane

- ANC activist, Gibson Ncube (also known by the surname Mondlane) by poisoning

- Matsela Polokela[43] – some TRC documents misspell the surname 'Pokolela'[44]

- Dulcie September in Paris – 29 March 1988. French Secret Service involvement is alleged.[3]

- David Webster – Wits University academic and anti-apartheid activist killed by Ferdi Barnard 1 May 1989, outside the Eleanor Street, Troyeville, Johannesburg home he shared with partner Maggie Friedman[4]

- Supplying materials to SAP members for the 1986 killing of KwaNdebele cabinet minister Piet Ntuli[5]

Operations planned but not executed

According to TRC records,[45][46][47] CCB operatives were tasked to seriously injure Martti Ahtisaari, UN Special Representative in Namibia,[48] and to eliminate the following:

- Gavin Evans

- Theo-Ben Gurirab (SWAPO)

- Hidipo Hamutenya (SWAPO)

- Pallo Jordan and Ronnie Kasrils[49]

- Gwen Lister (SWAPO)

- Winnie Mandela

- Kwenza Mhlaba

- Jay Naidoo

- Joe Slovo

- Stompie Sepei

- Oliver Tambo

- Daniel Tjongarero (SWAPO)

- Andimba Toivo ya Toivo (SWAPO)

- Roland White

Known associates

While the CCB was a section of the SADF's Special Forces they were joined on many operations by individuals from other parts of the state's broad security apparatus,[50] sometimes making it difficult to ascertain whether a specific person was part of the CCB or not. Of the estimated one hundred covert members, evidence exists that the following individuals were deployed as administrators or operatives:[51]

Senior military decision-makers

- Magnus Malan – General, Minister of Defence (1980–1991)

- Jannie Geldenhuys – General, and Chief of the SADF (1985–1990)[52]

- Joep Joubert – held the rank of major general, Chairman of the management board (1985–89)

- Kat Liebenberg – General, and Chief of the SADF (1991–1993)

- Eddie Webb – held the rank of major general, Chairman of the management board (1989–1990)

- Pieter Johan Verster – mostly known as 'Joe' Verster, aliases 'Gerhard',[53] 'Dave Martin', 'Jack van Staden' and 'Rick van Staden', held the rank of colonel, CCB Managing Director or general manager

Operatives and associates

- Donald Dolan Acheson – an Irish mercenary nicknamed 'The Cleaner'[54]

- Eeben Barlow – also referred to incorrectly as "Eeban Barlow", intelligence operative, ex-member of 32 Battalion and at one point commander of Region 5[55]

- Ferdi Barnard – prominent Region 6 operative, convicted and jailed in 1998 for the murder of David Webster[56]

- Wouter Jacobus Basson – alias Christo Britz, one time coordinator of the Zimbabwe unit, not to be confused with his cousin Dr. Wouter Basson[57]

- Johannes Basson[58]

- Barry Bawden – cousin of Kit and Gary, Region 4 operative and member of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[59]

- Guy Bawden – brother of Kit, Region 4 operative and member of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[59]

- Kit Bawden – Region 4 operative and head of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[59]

- Petrus Foster Botes – alias Bobby Greeff,[50] held the rank of captain

- Carl Casteling Botha – nicknamed Calla, a one time forward for the Transvaal rugby team[60]

- Gray Branfield – alias major Brian, and Mr. Z,[61] killed 2004 in Kut, Iraq during a gunfight between Shi'ite radicals and Ukrainian forces[62]

- Ron Butterweck – a German (or Dutch?) mercenary/agent, active in Angola around 1985/86

- Phillip Conjwayo – Zimbabwean policeman, Region 4 operative and peripheral member of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[59]

- José Daniels – CCB operator working for Petrus Botes, in the period just prior to the first democratic elections in Namibia, was instructed to dump four bottles containing cholera bacterium into the water supply of a camp near Windhoek[63]

- Daniel du Toit Burger – also referred to as Daniël Ferdinand du Toit,[64] alias Staal (meaning steel in Afrikaans) Burger also the name of an Afrikaans radio comedy of the time,[65] held the rank of colonel, erstwhile owner of the Breakers Hotel in Berea, Johannesburg[66] and minder of a state-funded brothel,[67] recruited into the CCB by Verster on 1 June 1988 after vacating his position as head of the SAP's Brixton Murder and Robbery Unit[68]

- Trevor Mark Floyd[69] – testified in the trial of Wouter Basson that he smeared poisonous ointment received from Basson[70] on the door handle of the car belonging to Peter Kalangula; Basson denied the allegation; Implicated in the same trial by Danie Phaal, a Project Barnacle colleague, of murdering a fellow operator known only as Christopher in February 1983[71]

- Dawid Fourie – alias 'Heine Müller', held the rank of commandant and one time deputy head of the CCB[72]

- Edward James Gordon – nicknamed 'Peaches', informer, involved in the attempt on the life of Dullah Omar[73]

- [Gordon Proudfoot] – Special Forces operative associate of Ferdi Barnard[74]

- André Wilhelmus Groenewald – alias Kobus Pienaar[75]

- Isgak Hardien – nicknamed Gakkie, an informer and gangster based in the Western Cape who earned R18,000 for placing a limpet mine on the premises of the Early Learning Centre[76]

- Theodore Hermansen[75]

- André Klopper[77]

- Koos – CCB medical coordinator, who received, on the instructions of Wouter Basson, 16 bottles containing the cholera bacterium on 4 August 1989, and six more twelve days later from Dr. A. Immelman of Roodeplaat Research Laboratories[63]

- David Komansky, (not to be confused with the Merrill Lynch executive of the same name) a commodities broker from Johannesburg who received R29 million from the CCB to establish a business in Britain for procuring arms.[78]

- Theuns Kruger – alias 'Jaco Black', financial manager

- Kobus le Roux implicated with Ferdi Barnard in the plot to kill Ahtisaari[33]

- Jackie Lonte – recruited to deal with United Democratic Front supporters, founder of the 10,000 strong Cape Flats gang 'The Americans'

- Hans Louw[79][80]– claimed he belonged to a squad which plotted to kill president Samora Machel

- Lafras Luitingh – held the rank of major, one time coordinator of Zimbabwe unit[81]

- Leon André Maree – nickname 'Chappies' (also the name of a popular South African chewing gum)

- Cornelius Alwyn Johannes Meerholz – nicknamed Corrie, alias 'Kerneels Koekemoer', held the rank of commandant, after transferring to 5 Reconnaissance Regiment

- Tai Minnaar[82] – once held the rank of major-general in the SADF, founder member of the Bureau of State Security, had been a CIA operative in 1970s Cuba[83]

- Mr C – operated in Mozambique and Swaziland, once delivered a parcel to Windhoek on behalf of Pieter (most likely Petrus) Botes[84]

- Mr R – alias 'Frans Brink', medical doctor, member until the beginning of 1990[85]

- Edwin Mudingi, former Selous Scout member of the same cell as Hans Louw[86]

- Christoffel Nel – alias 'Derek Louw', held the rank of colonel, one time head of intelligence unit[42][72]

- Johan Niemoller Jr. – also referred to as Joseph Niemoller, until 1987 coordinator of (European and International) unit

- Nico Palm[87] – foreign operative, involved in the CCB front company Geo International Trading as an explosives expert

- Danie Phaal[88] – or DJ Phaal,[63] CCB head of security, also known as Frank, James or Johan

- Jao Pinta – involved in the murder of Florence and Fabian Ribeiro[89]

- Ruiz da Silva – involved in the murder of Florence and Fabian Ribeiro[89]

- Eugene Riley[90] – also referred to as Eugene Reilly

- Noel Robey – involved in the murder of Florence and Fabian Ribeiro[89]

- Michael Smith – ex-Rhodesian soldier, Region 4 operative and member of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[91]

- Migiel Sven Smuts-Muller – ex-31 Battalion member[85]

- Peter Stanton – ex-Rhodesian, intelligence operative[72]

- Pierre Theron – auditor of CCB books and keeper of share transfer certificates for related front companies[92]

- Ian Strange – alias Rodney, involved in the Angola, Zambia and Tanzania region[72]

- Alan Trowsdale[72]

- Charles Wildschudt (formerly Neelse)[72]

- Stefaans van der Walt – alias Anton du Randt[85]

- Willie van Deventer – claimed membership of CCB, and to have been part of the Gaborone raid in which ANC member, Matsela Pokolela, was killed[93]

- Roelf van Heerden – alias 'Roelf van der Westhuizen', one time head of South West Africa operations[72]

- Ferdi van Wyk[94] – Brigadier, also named as the Military Intelligence contact used by Marthinus van Schalkwyk in the covert funding of the front organization Jeugkrag[95]

- Abram van Zyl – aliases 'Thinus de Wet'[96] and 'Andries Rossouw', nickname 'Slang' (pronounced 'slung', means snake in Afrikaans), responsible for the Western Cape operations of Region Six, and for Ferdi Barnard; left the CCB in October 1989

- Leonard Veenendal[97]

- Athol Visser[98] – nickname 'Ivan the Terrible', a high-ranking CCB operative, posted to London in the 1980s to plan the elimination of key opponents of apartheid that allegedly included Swedish prime minister Olof Palme.

- Gary Strout – Region 4 operative and member of Zimbabwe-based CCB cell known as Juliet[59]

- Eugene Halliday[99] – alias "Wolf", was a member of the Experimental Group Program, linked to the assassination of Godfrey Mafuya[100] in Saulsville (1985) and several other "enemies of state" throughout Africa. His involvement in European missions has has never been confirmed

Associates who died mysteriously

- Edward James Gordon – killed 1991[101]

- André Klopper – murdered Thursday 11 May 1995 a week after amnesty ensured his release from jail; found next to a road in Elandsfontein; ex-SADF Special Forces members Mathys de Villiers (Kaalvoet Thysie) and Heckie Horn were tried for his murder and acquitted[102]

- Jackie Lonte – murdered in the 1990s[103]

- "Corrie" Alwyn Meerholtz – died in a car crash on 24 November 1989[104]

- Tai Minnaar – died in September 2002[105] after a chemical and biological weapons deal in which he was involved went wrong[106]

- Eugene Riley – was killed in January 1994[107] after probing the killing of Chris Hani[108][109]) – Died under suspicious circumstances.[85]

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Although the entire truth about the Civil Cooperation Bureau may never be known, South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC) concluded that:[110]

"...the CCB was a creation of the SADF and an integral part of South Africa's counter-insurgency system which, in the course of its operations, perpetrated gross violations of human rights, including killings, against both South African and non-South African citizens. The Commission finds that the activities of the CCB constituted a systematic pattern of abuse which entailed deliberate planning on the part of the leadership of the CCB and the SADF. The Commission finds these institutions and their members accountable for the aforesaid gross violations of human rights."

As per the policy of the TRC, its findings were set out, but no action was taken.

According to General Malan, the CCB's three objectives—comparable to those of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE)—were:

- to infiltrate and penetrate the enemy;

- to gather Information; and

- to disrupt the enemy.

In his testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Malan declared that he had never issued an order or authorised an order for the assassination of anybody, and that the killing of political opponents of the government never formed part of the brief of the South African Defence Force.[111]

Negative outcomes

The front company Oceantec among others was used to embezzle $100 million US from private investors and a collateral trading house as part of a supposed sanctions busting operation between 1989 and 1991.[112]

CCB member Eben Barlow and Michael Mullen recruited other CCB members to start Executive Outcomes a private military contractor that provided combatants, training and equipment.

See also

- Boipatong Massacre

- Dirk Coetzee

- Eugene de Kock

- Delta G Scientific Company

- Executive Outcomes

- Lema

- National Intelligence Service

- Project Coast

- Protechnik

- Roodeplaat Research Laboratories

- State Security Council

- Craig Williamson

References

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, 2003, p. 39

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Author unknown. (1998). A self-confessed apartheid era assassin told the Pretoria High Court yesterday that he did not apply for amnesty for his deeds, with one exception, because he believed his seniors, who gave him the orders, were the ones who should be punished. Business Day.

- ^ a b Peter Batchelor; Kees Kingma; Guy Lamb (2004), Demilitarisation and Peace-building in Southern Africa, Ashgate Publishing Ltd, ISBN 0-7546-3315-2, retrieved 18 May 2008

- ^ a b Author unknown. (1998). Former Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) agent Ferdi Barnard has admitted for the first time to murdering activist and academic David Webster in 1989 on instructions of then bureau head, Joe Verster. Business Day.

- ^ a b SAPA. (1999). Joubert authorises car bomb that killed Piet Ntuli.

- ^ Sanders, J (2006), Apartheid's friends, London: John Murray, pp. 34–55

- ^ Sanders, J (2006), Apartheid's friends, London: John Murray, pp. 94–119

- ^ "Confession 'built case against Basson'". Daily Dispatch. 7 December 2000. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- ^ Gould, Chandr; Burger, Marlene (2000), The South African Chemical and Biological Warfare Programme, vol. Trial Report: Twenty-Eight., Centre for Conflict Resolution, retrieved 21 May 2007

- ^ Adri, Kotzé (30 August 1997), "Marthinus `moet om amnestie vra, soos ANC-spioene'", Beeld, archived from the original (– Scholar search) on 27 September 2007

{{citation}}: External link in|format=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ken, Silverstein (17 April 2006), "The Making of a Lobbyist", Harper's Magazine

- ^ Engelbrecht, Leon (1 November 2006), "The life and times of PW Botha", IOL

- ^ Malan admits setting up CCB, ordering raids, Cape Town, 7 May 1997, retrieved 21 May 2007

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gear, Sasha (2000), Now that the War is Over. Ex-combatants Transition and the Question of Violence: A literature review, Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation., archived from the original (– Scholar search) on 20 October 2006, retrieved 24 May 2007

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - ^ O'Brien, Kevin. "The Use of Assassination as a Tool of State Policy: South Africa's Counter-Revolutionary Strategy 1979-92 (Part II)." Terrorism and Political Violence 13.2 (2001): 131

- ^ Submission to The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Gen MA de Malan, 2003, p. 28

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The Transformation of Military Intelligence and Special Forces. Towards an Accountable and Transparent Military Culture.", South African Defence Review, vol. 12, 1993, retrieved 16 May 2007

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, pp. 137-8. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ^ Human Rights Watch. (1991). The Killings in South Africa: The Role of the Security Forces and the Response of the State. ISBN 0-929692-76-4. Accessed 16 May 2007

- ^ Transcript of proceedings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (Day 18), 29 September 2000. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, pp. 139. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ^ a b O'Brien, Kevin A. The South African Intelligence Services: From Apartheid to Democracy, 1948-2005. Routledge, 2010., pg. 134-135

- ^ a b Barlow, E. (2007). Executive Outcomes. Against all odds. Alberton, South Africa: Galago.

- ^ Burger, Marlene (29 April 2000). "Basson trial to reveal dark CCB secrets". Sunday Independent. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Gould, C; Burger, M. (n.d.). "The South African Chemical and Biological Warfare Programme. Trial Report: Thirty-Three". University of Cape Town: Centre for Conflict Resolution. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ^ Barlow's most challenging assignment: heading up the Western European section of the CCB

- ^ a b Amnesty Committee. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. Application in terms of section 18 of the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, 34 of 1995. AC/2001/232. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Coleman, Max. "Apartheid - A Crime Against Humanity: The Unfolding of Total Strategy 1948-1989: Covert Operations". South African History Online. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Author unknown. (2005). Die geskiedenis van Vrye Weekblad in 170 bladsye. Die Burger. Accessed 12 December 2007

- ^ Author unknown. (2007). Van bliksem tot grotman. Die Burger. Accessed 12 December 2007

- ^ Associated Press. (1990). Paper Says Pretoria Put Germs in Namibian Water. New York Times, 12 May. Accessed 17 May 2007..

- ^ Burgess, S. & Purkitt, H. (undated). The secret program. South Africa's chemical and biological weapons. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ a b Targeted by the Civil Cooperation Bureau

- ^ von Paleske, A. (undated). Woods was part of murky past. The Zimbabwean. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission Video Collection. Yale Law School Lilian Goldman Library. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Structures and personnel of the ANC and MK

- ^ Author unknown. (1998). The top structure of the defence force's Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) had given the go-ahead in 1989 for the elimination of Dullah Omar and offered a well-known Cape Flats gangster R15 000 to gun down the future justice minister, the high court heard yesterday. Business Day. Accessed 16 May 2007.

- ^ "OMAR WAS LUCKY BARNARD DIDN'T KILL HIM: PTA HIGH COURT TOLD". SAPA. 30 March 1998. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ Stiff, Peter (2001), Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s., Alberton, South Africa: Galago, p. 266

- ^ Ashley, Smith (16 March 2000), "I won't apologise, says CCB boss", Cape Argus

- ^ Baboon foetus 'sent to bewitch Tutu’. Independent Newspapers Youthvote.

- ^ a b Author unknown. (1998). TRC clears Lubowski's name. The Namibian. Accessed 21 May 2007.

- ^ African National Congress, List of ANC Members who Died in Exile. March 1960 – December 1993. Accessed 21 May 2007

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, p. 110. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, p. 141. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ^ Walker, A. (2000). How an assassin bungled a deadly umbrella plot The Independent, 13 May.

- ^ SAPA. (1998). Winnie and Tutu were on Ferdi Barnard's hit list: ex-wife

- ^ Transcript of proceedings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa (Day 17), 28 September 2000. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Author unknown. (2000). A self-confessed apartheid era assassin told the Pretoria High Court yesterday that he did not apply for amnesty for his deeds, with one exception, because he believed his seniors, who gave him the orders, were the ones who should be punished. Business Day. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ a b Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. (2000). Transcript of proceedings: Amnesty Hearing of Henri van der Westhuizen. Application no: AM8079/97. (Day 1), October, 9. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, pp. 80, 82, 89, 110, 120, 136-8, 139, 140. Retrieved 4 May 2007

- ^ Stiff, Peter (2001), Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s., Alberton, South Africa: Galago, p. 315

- ^ Stiff, Peter (2001), Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s., Alberton, South Africa: Galago, p. 375

- ^ Stiff, P. (2001). Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s. Alberton, South Africa: Galago. pp 389.

- ^ Author unknown. (2007). Eeben Barlow on the record. Molotov Cocktail, 1, 9-13.

- ^ SAPA. (1998). Former CCB agent Ferdi Barnard convicted of murder. Accessed 16 May 2007.

- ^ Gould, C. & Burger, M. (unknown)The South African Chemical and Biological Warfare Programme. Trial Report: Thirty-Seven. Centre for Conflict Resolution. Accessed 17 May 2007.

- ^ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, p. 142, accessed 4 May 2007

- ^ a b c d e Schwegler, O, & Watts, D. (2006) Kevin Woods. Exclusive interview. Carte Blanche. Broadcast date: 23 July. Accessed 3 December 2007.

- ^ Author unknown. (2001). Colonel's orders: follow Evans, kill him! Dispatch, Wednesday, 27 June. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ NTI. South Africa profile. Biological overview. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ Gavin du Venage, The Australian, Apartheid assassins meet match in Iraq, 27 April 2004, accessed 16 May 2007

- ^ a b c The State vs Wouter Basson, Case CCT 30/03 (Constitutional Court of South Africa 10 March 2004).

- ^ Menges, W. (1999). SA cops cautious on Lubowski progress. The Namibian, 6 August. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ Springbok Radio. Archives. A list of programme titles that have been archived. Accessed 4 May 2007.

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ a b c d e f g Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Vol 2, Sec 2 Accessed 3 December 2007.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ [7]

- ^ a b [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ [10]

- ^ Heidenheimer, Arnold J.; Michael Johnston (2002), Political corruption: Concepts & Contexts, Edison, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, p. 407, ISBN 978-0-7658-0761-8

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 2011-11-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "FORMER CCB MAN LIED TO HARMS COMMISSION ABOUT WEBSTER". SAPA. 18 March 1998. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- ^ [11]

- ^ Warrick, J. & Mintz, J. (2003). Lethal Legacy: Bioweapons for Sale. Washington Post, Sunday, 20 April; Page A01. Accessed 22 May 2007.

- ^ [12]

- ^ a b c d [13]

- ^ Commey, Pusch (April 2003), Mozambique/South Africa: Who killed Samora Machel?, vol. New African, FindArticles, retrieved 17 April 2008

- ^ [14]

- ^ [15]

- ^ a b c [16]

- ^ [17]

- ^ [18]

- ^ [19]

- ^ [20]

- ^ Adri Kotzé, Beeld, Veldtog van BSB moes ANC `diskrediteer' `Wou ondergrondse strukture skep', 1997, accessed 16 May

- ^ Peta Thornycroft, Mail and Guardian, Shady past of FW's heir, 29 Aug 1997, accessed 16 May 2007

- ^ Transcript of an Amnesty Hearing, Day 15, Freeman Centre, Greenpoint, Cape Town: Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2000

- ^ [21]

- ^ [22]

- ^ https://plus.google.com/112689766446532642869/posts/aV7Hv4VUGbq

- ^ http://sabctrc.saha.org.za/victims/mafuya_godfrey.htm?tab=report

- ^ Regional Office Reports

- ^ Taljaard, Jan (15 June 1995), "Kaalvoet's storming nights at the Bastille" (– Scholar search), Mail & Guardian

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - ^ [23]

- ^ Stiff, P. (2001). Warfare by other means. South Africa in the 1980s and 1990s. Alberton, South Africa: Galago. pp 413-4.

- ^ [24]

- ^ [25]

- ^ [26]

- ^ – (Luitenant – SADF attached to Special Force)

- ^ South African Special Forces League ::

- ^ "The State outside South Africa between 1960 and 1990", Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report, Volume 2, Chapter 2, News24, 1993, retrieved 5 December 2007

- ^ General Malan's submission to the TRC - Section 15: The Civil Cooperation Bureau

- ^ "Us Bankers Sue South African Government".

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from July 2008

- Apartheid government

- Cold War military history of South Africa

- Organisations associated with apartheid

- Defunct organisations of South Africa

- Special forces of South Africa

- Defunct South African intelligence agencies

- 1988 establishments in South Africa

- 1990 disestablishments in South Africa