Cybernetics

Cybernetics is a transdisciplinary[1] approach for exploring regulatory systems, their structures, constraints, and possibilities. In the 21st century, the term is often used in a rather loose way to imply "control of any system using technology;" this has blunted its meaning to such an extent that many writers avoid using it.

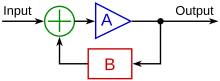

Cybernetics is relevant to the study of systems, such as mechanical, physical, biological, cognitive, and social systems. Cybernetics is applicable when a system being analyzed incorporates a closed signaling loop; that is, where action by the system generates some change in its environment and that change is reflected in that system in some manner (feedback) that triggers a system change, originally referred to as a "circular causal" relationship.

System dynamics, a related field, originated with applications of electrical engineering control theory to other kinds of simulation models (especially business systems) by Jay Forrester at MIT in the 1950s.

Concepts studied by cyberneticists include, but are not limited to: learning, cognition, adaptation, social control, emergence, communication, efficiency, efficacy, and connectivity. These concepts are studied by other subjects such as engineering and biology, but in cybernetics these are abstracted from the context of the individual organism or device.

Norbert Wiener defined cybernetics in 1948 as "the scientific study of control and communication in the animal and the machine."[2] The word cybernetics comes from Greek κυβερνητική (kybernetike), meaning "governance", i.e., all that are pertinent to κυβερνάω (kybernao), the latter meaning "to steer, navigate or govern", hence κυβέρνησις (kybernesis), meaning "government", is the government while κυβερνήτης (kybernetes) is the governor or the captain. Contemporary cybernetics began as an interdisciplinary study connecting the fields of control systems, electrical network theory, mechanical engineering, logic modeling, evolutionary biology, neuroscience, anthropology, and psychology in the 1940s, often attributed to the Macy Conferences. During the second half of the 20th century cybernetics evolved in ways that distinguish first-order cybernetics (about observed systems) from second-order cybernetics (about observing systems).[3] More recently there is talk about a third-order cybernetics (doing in ways that embraces first and second-order).[4]

Fields of study which have influenced or been influenced by cybernetics include game theory, system theory (a mathematical counterpart to cybernetics), perceptual control theory, sociology, psychology (especially neuropsychology, behavioral psychology, cognitive psychology), philosophy, architecture, and organizational theory.[5]

Definitions

Cybernetics has been defined in a variety of ways, by a variety of people, from a variety of disciplines. The Larry Richards Reader includes a listing by Stuart Umpleby of notable definitions:[6]

- "Science concerned with the study of systems of any nature which are capable of receiving, storing and processing information so as to use it for control." — A. N. Kolmogorov

- "The art of securing efficient operation." — Louis Couffignal[7]

- "'The art of steersmanship': deals with all forms of behavior in so far as they are regular, or determinate, or reproducible: stands to the real machine -- electronic, mechanical, neural, or economic -- much as geometry stands to real object in our terrestrial space; offers a method for the scientific treatment of the system in which complexity is outstanding and too important to be ignored." — W. Ross Ashby

- "A branch of mathematics dealing with problems of control, recursiveness, and information, focuses on forms and the patterns that connect." — Gregory Bateson

- "The art of effective organization." — Stafford Beer

- "The art and science of manipulating defensible metaphors." — Gordon Pask

- "The art of creating equilibrium in a world of constraints and possibilities." — Ernst von Glasersfeld

- "The science and art of understanding." — Humberto Maturana

- "The ability to cure all temporary truth of eternal triteness." — Herbert Brun

Other notable definitions include:

- "The science and art of the understanding of understanding." — Rodney E. Donaldson, the first president of the American Society for Cybernetics

- "A way of thinking about ways of thinking of which it is one." — Larry Richards

- "The art of interaction in dynamic networks." — Roy Ascott

Etymology

The term cybernetics stems from κυβερνήτης (kybernētēs) "steersman, governor, pilot, or rudder". As with the ancient Greek pilot, independence of thought is important in cybernetics.[8] Cybernetics is a broad field of study, but the essential goal of cybernetics is to understand and define the functions and processes of systems that have goals and that participate in circular, causal chains that move from action to sensing to comparison with desired goal, and again to action. Studies in cybernetics provide a means for examining the design and function of any system, including social systems such as business management and organizational learning, including for the purpose of making them more efficient and effective.

French physicist and mathematician André-Marie Ampère first coined the word "cybernetique" in his 1834 essay Essai sur la philosophie des sciences to describe the science of civil government.[9]

Cybernetics was borrowed by Norbert Wiener, in his book "Cybernetics", to define the study of control and communication in the animal and the machine.[10] Stafford Beer called it the science of effective organization and Gordon Pask called it "the art of defensible metaphors" (emphasizing its constructivist epistemology) though he later extended it to include information flows "in all media" from stars to brains. It includes the study of feedback, black boxes and derived concepts such as communication and control in living organisms, machines and organizations including self-organization. Its focus is how anything (digital, mechanical or biological) processes information, reacts to information, and changes or can be changed to better accomplish the first two tasks.[11] A more philosophical definition, suggested in 1956 by Louis Couffignal, one of the pioneers of cybernetics, characterizes cybernetics as "the art of ensuring the efficacy of action."[12] The most recent definition has been proposed by Louis Kauffman, President of the American Society for Cybernetics, "Cybernetics is the study of systems and processes that interact with themselves and produce themselves from themselves."[13]

History

Roots of cybernetic theory

The word cybernetics was first used in the context of "the study of self-governance" by Plato in The Alcibiades to signify the governance of people.[14] The word 'cybernétique' was also used in 1834 by the physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836) to denote the sciences of government in his classification system of human knowledge.

The first artificial automatic regulatory system, a water clock, was invented by the mechanician Ktesibios. In his water clocks, water flowed from a source such as a holding tank into a reservoir, then from the reservoir to the mechanisms of the clock. Ktesibios's device used a cone-shaped float to monitor the level of the water in its reservoir and adjust the rate of flow of the water accordingly to maintain a constant level of water in the reservoir, so that it neither overflowed nor was allowed to run dry. This was the first artificial truly automatic self-regulatory device that required no outside intervention between the feedback and the controls of the mechanism. Although they did not refer to this concept by the name of Cybernetics (they considered it a field of engineering), Ktesibios and others such as Heron and Su Song are considered to be some of the first to study cybernetic principles.

The study of teleological mechanisms (from the Greek τέλος or telos for end, goal, or purpose) in machines with corrective feedback dates from as far back as the late 18th century when James Watt's steam engine was equipped with a governor (1775-1800), a centrifugal feedback valve for controlling the speed of the engine. Alfred Russel Wallace identified this as the principle of evolution in his famous 1858 paper.[15] In 1868 James Clerk Maxwell published a theoretical article on governors, one of the first to discuss and refine the principles of self-regulating devices. Jakob von Uexküll applied the feedback mechanism via his model of functional cycle (Funktionskreis) in order to explain animal behaviour and the origins of meaning in general.

Early 20th century

Contemporary cybernetics began as an interdisciplinary study connecting the fields of control systems, electrical network theory, mechanical engineering, logic modeling, evolutionary biology and neuroscience in the 1940s. Electronic control systems originated with the 1927 work of Bell Telephone Laboratories engineer Harold S. Black on using negative feedback to control amplifiers. The ideas are also related to the biological work of Ludwig von Bertalanffy in General Systems Theory.

Early applications of negative feedback in electronic circuits included the control of gun mounts and radar antenna during World War II. Jay Forrester, a graduate student at the Servomechanisms Laboratory at MIT during WWII working with Gordon S. Brown to develop electronic control systems for the U.S. Navy, later applied these ideas to social organizations such as corporations and cities as an original organizer of the MIT School of Industrial Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management. Forrester is known as the founder of System Dynamics.

W. Edwards Deming, the Total Quality Management guru for whom Japan named its top post-WWII industrial prize, was an intern at Bell Telephone Labs in 1927 and may have been influenced by network theory. Deming made "Understanding Systems" one of the four pillars of what he described as "Profound Knowledge" in his book "The New Economics."

Numerous papers spearheaded the coalescing of the field. In 1935 Russian physiologist P.K. Anokhin published a book in which the concept of feedback ("back afferentation") was studied. The study and mathematical modelling of regulatory processes became a continuing research effort and two key articles were published in 1943. These papers were "Behavior, Purpose and Teleology" by Arturo Rosenblueth, Norbert Wiener, and Julian Bigelow; and the paper "A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity" by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts.

In 1936, Odobleja publishes "Phonoscopy and the clinical semiotics". In 1937, he participates in the IXth International Congress of Military Medicine with a paper entitled "Demonstration de phonoscopie", where he disseminates a prospectus in French, announcing the appearance of his future work "The Consonantist Psychology".[1]

The most important of his writings is Psychologie consonantiste, in which Odobleja lays the theoretical foundations of the generalized cybernetics. The book, published in Paris by "Librairie Maloine" (vol. I in 1938 and vol. II in 1939), contains almost 900 pages and includes 300 figures in the text.[2] The author wrote at the time that "this book is... a table of contents, an index or a dictionary of psychology, [for] a ... great Treatise of Psychology that should contain 20–30 volumes".

Due to the beginning of World War II, the publication went unnoticed. The first Romanian edition of this work did not appear until 1982 (the first edition was published in French). Cybernetics as a discipline was firmly established by Norbert Wiener, McCulloch and others, such as W. Ross Ashby, mathematician Alan Turing, and W. Grey Walter. Walter was one of the first to build autonomous robots as an aid to the study of animal behaviour. Together with the US and UK, an important geographical locus of early cybernetics was France.

In the spring of 1947, Wiener was invited to a congress on harmonic analysis, held in Nancy, France. The event was organized by the Bourbaki, a French scientific society, and mathematician Szolem Mandelbrojt (1899–1983), uncle of the world-famous mathematician Benoît Mandelbrot.

During this stay in France, Wiener received the offer to write a manuscript on the unifying character of this part of applied mathematics, which is found in the study of Brownian motion and in telecommunication engineering. The following summer, back in the United States, Wiener decided to introduce the neologism cybernetics into his scientific theory. The name cybernetics was coined to denote the study of "teleological mechanisms" and was popularized through his book Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (MIT Press/John Wiley and Sons, NY, 1948). In the UK this became the focus for the Ratio Club.

In the early 1940s John von Neumann, although better known for his work in mathematics and computer science, did contribute a unique and unusual addition to the world of cybernetics: von Neumann cellular automata, and their logical follow up the von Neumann Universal Constructor. The result of these deceptively simple thought-experiments was the concept of self replication which cybernetics adopted as a core concept. The concept that the same properties of genetic reproduction applied to social memes, living cells, and even computer viruses is further proof of the somewhat surprising universality of cybernetic study.

Wiener popularized the social implications of cybernetics, drawing analogies between automatic systems (such as a regulated steam engine) and human institutions in his best-selling The Human Use of Human Beings : Cybernetics and Society (Houghton-Mifflin, 1950).

While not the only instance of a research organization focused on cybernetics, the Biological Computer Lab at the University of Illinois, Urbana/Champaign, under the direction of Heinz von Foerster, was a major center of cybernetic research for almost 20 years, beginning in 1958.

Split from artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence (AI) was founded as a distinct discipline at the Dartmouth Conferences. After some uneasy coexistence, AI gained funding and prominence. Consequently, cybernetic sciences such as the study of neural networks were downplayed; the discipline shifted into the world of social sciences and therapy.[16]

Prominent cyberneticians during this period include:

New cybernetics

In the 1970s, new cyberneticians emerged in multiple fields, but especially in biology. The ideas of Maturana, Varela and Atlan, according to Jean-Pierre Dupuy (1986) "realized that the cybernetic metaphors of the program upon which molecular biology had been based rendered a conception of the autonomy of the living being impossible. Consequently, these thinkers were led to invent a new cybernetics, one more suited to the organizations which mankind discovers in nature - organizations he has not himself invented".[17] However, during the 1980s the question of whether the features of this new cybernetics could be applied to social forms of organization remained open to debate.[17]

In political science, Project Cybersyn attempted to introduce a cybernetically controlled economy during the early 1970s. In the 1980s, according to Harries-Jones (1988) "unlike its predecessor, the new cybernetics concerns itself with the interaction of autonomous political actors and subgroups, and the practical and reflexive consciousness of the subjects who produce and reproduce the structure of a political community. A dominant consideration is that of recursiveness, or self-reference of political action both with regards to the expression of political consciousness and with the ways in which systems build upon themselves".[18]

One characteristic of the emerging new cybernetics considered in that time by Felix Geyer and Hans van der Zouwen, according to Bailey (1994),[19] was "that it views information as constructed and reconstructed by an individual interacting with the environment. This provides an epistemological foundation of science, by viewing it as observer-dependent. Another characteristic of the new cybernetics is its contribution towards bridging the micro-macro gap. That is, it links the individual with the society".[19] Another characteristic noted was the "transition from classical cybernetics to the new cybernetics [that] involves a transition from classical problems to new problems. These shifts in thinking involve, among others, (a) a change from emphasis on the system being steered to the system doing the steering, and the factor which guides the steering decisions.; and (b) new emphasis on communication between several systems which are trying to steer each other".[19]

Recent endeavors into the true focus of cybernetics, systems of control and emergent behavior, by such related fields as game theory (the analysis of group interaction), systems of feedback in evolution, and metamaterials (the study of materials with properties beyond the Newtonian properties of their constituent atoms), have led to a revived interest in this increasingly relevant field.[11]

Cybernetics and economic systems

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

The design of self-regulating control systems for a real-time planned economy was explored by Viktor Glushkov in the former Soviet Union during the 1960s. By the time information technology was developed enough to enable feasible economic planning based on computers, the Soviet Union and eastern bloc countries began moving away from planning[20] and eventually collapsed.

More recent proposals for socialism involve "New Socialism", outlined by the computer scientists Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell, where computers determine and manage the flows and allocation of resources among socially-owned enterprises.[21]

Subdivisions of the field

Cybernetics is sometimes used as a generic term, which serves as an umbrella for many systems-related scientific fields.

Basic cybernetics

Cybernetics studies systems of control as a concept, attempting to discover the basic principles underlying such things as

- Artificial intelligence

- Robotics

- Computer Vision

- Control systems

- Emergence

- Learning organization

- New Cybernetics

- Second-order cybernetics

- Interactions of Actors Theory

- Conversation Theory

- Self-organization in cybernetics

In biology

Cybernetics in biology is the study of cybernetic systems present in biological organisms, primarily focusing on how animals adapt to their environment, and how information in the form of genes is passed from generation to generation.[22] There is also a secondary focus on combining artificial systems with biological systems.[citation needed] A notable application to the biology world would be that, in 1955, the physicist George Gamow published a prescient article in Scientific American called “Information transfer in the living cell,” and cybernetics gave biologists Jacques Monod and François Jacob a language for formulating their early theory of gene regulatory networks in the 1960s.[23]

- Bioengineering

- Biocybernetics

- Bionics

- Homeostasis

- Heterostasis

- Medical cybernetics

- Practopoiesis

- Synthetic Biology

- Systems Biology

- Autopoiesis

- Neuroscience

In computer science

Computer science directly applies the concepts of cybernetics to the control of devices and the analysis of information.

In engineering

Cybernetics in engineering is used to analyze cascading failures and System Accidents, in which the small errors and imperfections in a system can generate disasters. Other topics studied include:

In management

- Entrepreneurial cybernetics

- Management cybernetics

- Organizational cybernetics

- Operations research

- Systems engineering

In mathematics

Mathematical Cybernetics focuses on the factors of information, interaction of parts in systems, and the structure of systems.

In psychology

- Homunculus

- Psycho-Cybernetics

- Systems psychology

- Perceptual Control Theory

- Psychovector Analysis

- Attachment Theory

- Human-robot interaction

- Consciousness

- Embodied cognition

- Cognitive psychology

- Mind-body problem

- Behavioral cybernetics

In sociology

By examining group behavior through the lens of cybernetics, sociologists can seek the reasons for such spontaneous events as smart mobs and riots, as well as how communities develop rules such as etiquette by consensus without formal discussion[citation needed]. Affect Control Theory explains role behavior, emotions, and labeling theory in terms of homeostatic maintenance of sentiments associated with cultural categories. The most comprehensive attempt ever made in the social sciences to increase cybernetics in a generalized theory of society was made by Talcott Parsons. In this way, cybernetics establishes the basic hierarchy in Parsons' AGIL paradigm, which is the ordering system-dimension of his action theory. These and other cybernetic models in sociology are reviewed in a book edited by McClelland and Fararo.[24]

In education

A model of cybernetics in Education was introduced by Gihan Sami Soliman; an educational consultant, as a project idea to be implemented with the help of two team members in Sinai. The Sinai Sustainability Cybernetics Center announced as a semi-finalist project by MIT annual competition 2013.[25][26][27][28] The project idea proposed relating education to sustainable development through an IMS project that applies a multiple educational program related to the original natural self-healing system of life on earth. Education, sustainable development, social justice disciplines interact in a causal circular relationship that education would contribute to the development of the local community in Sinai village, on both sustainability and social responsibility levels while the community itself provides a unique learning environment that will contribute to the development of the educational program in a closed signaling loop.

In art

Nicolas Schöffer's CYSP I (1956) was perhaps the first artwork to explicitly employ cybernetic principles (CYSP is an acronym that joins the first two letters of the words "CYbernetic" and "SPatiodynamic").[29] The artist Roy Ascott elaborated an extensive theory of cybernetic art in "Behaviourist Art and the Cybernetic Vision" (Cybernetica, Journal of the International Association for Cybernetics (Namur), Volume IX, No.4, 1966; Volume X No.1, 1967) and in "The Cybernetic Stance: My Process and Purpose" (Leonardo Vol 1, No 2, 1968). Art historian Edward A. Shanken has written about the history of art and cybernetics in essays including "Cybernetics and Art: Cultural Convergence in the 1960s"[30] and "From Cybernetics to Telematics: The Art, Pedagogy, and Theory of Roy Ascott"(2003),[31] which traces the trajectory of Ascott's work from cybernetic art to telematic art (art using computer networking as its medium, a precursor to net.art.)

In Earth system science

Geocybernetics aims to study and control the complex co-evolution of ecosphere and anthroposphere,[32] for example, for dealing with planetary problems such as anthropogenic global warming.[33] Geocybernetics applies a dynamical systems perspective to Earth system analysis. It provides a theoretical framework for studying the implications of following different sustainability paradigms on co-evolutionary trajectories of the planetary socio-ecological system to reveal attractors in this system, their stability, resilience and reachability. Concepts such as tipping elements and tipping points in the climate system, planetary boundaries, the safe operating space for humanity and proposals for manipulating Earth system dynamics on a global scale such as geoengineering have been framed in the language of geocybernetic Earth system analysis.

Related fields

Complexity science

Complexity science attempts to understand the nature of complex systems.

Biomechatronics

Biomechatronics relates to linking mechatronics to biological organisms, leading to systems that conform to A. N. Kolmogorov's definition of Cybernetics, i.e. "Science concerned with the study of systems of any nature which are capable of receiving, storing and processing information so as to use it for control".[citation needed] From this perspective mechatronics are considered technical cybernetics or engineering cybernetics.

See also

- Artificial life

- Automation

- Autopoiesis

- Brain-computer interface

- Chaos theory

- Connectionism

- Cyborg

- Decision theory

- Family therapy

- Earth system science

- Gaia hypothesis

- Industrial Ecology

- Intelligence amplification

- Management science

- Perceptual control theory

- Principia Cybernetica

- Project Cybersyn

- Viable System Model

- Semiotics

- Superorganisms

- Synergetics

- Variety (cybernetics)

- Viable Systems Approach

References

- ^ Müller, Albert (2000). "A Brief History of the BCL". Österreichische Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaften. 11 (1): 9–30.

- ^ Wiener, Norbert (1948). Cybernetics, or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- ^ Heinz von Foerster (1981), 'Observing Systems", Intersystems Publications, Seaside, CA. OCLC 263576422

- ^ Kenny, Vincent (15 March 2009). "There's Nothing Like the Real Thing". Revisiting the Need for a Third-Order Cybernetics". Constructivist Foundations. 4 (2): 100–111. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ^ Tange, Kenzo (1966) "Function, Structure and Symbol".

- ^ Stuart Umpleby (2008). "Definitions of Cybernetics". The Larry Richards Reader 1997–2007 (PDF). pp. 9–11.

I developed this list of definitions/descriptions in 1987-88 and have been distributing it at ASC (American Society for Cybernetics)conferences since 1988. I added a few items to the list over the next two years, and it has remained essentially unchanged since then. My intent was twofold: (1) to demonstrate that one of the distinguishing features of cybernetics might be that it could legitimately have multiple definitions without contradicting itself, and (2) to stimulate dialogue on what the motivations (intentions, desires, etc.) of those who have proposed different definitions might be.

- ^ "La cybernétique est l’art de l’efficacité de l’action" originally a french definition formulated in 1953, lit. "Cybernetics is the art of effective action"

- ^ Leary,Timothy. "The Cyberpunk: the individual as reality pilot" in Storming the Reality Studio. Duke University Press: 1991.

- ^ H.S. Tsien Engineering Cybernetics, Preface vii, 1954 McGraw Hill

- ^ Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 1948 MIT Press

- ^ a b Kelly, Kevin (1994). Out of control: The new biology of machines, social systems and the economic world. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-48340-8. OCLC 221860672.

- ^ Couffignal, Louis, "Essai d’une définition générale de la cybernétique", The First International Congress on Cybernetics, Namur, Belgium, June 26–29, 1956, Gauthier-Villars, Paris, 1958, pp. 46-54

- ^ CYBCON discusstion group 20 September 2007 18:15

- ^ Johnson, Barnabas. "The Cybernetics of Society". Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- ^ http://people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S043.htm

- ^ Cariani, Peter (15 March 2010). "on the importance of being emergent". Constructivist Foundations. 5 (2): 89. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

artificial intelligence was born at a conference at dartmouth in 1956 that was organized by McCarthy, Minsky, rochester, and shannon, three years after the Macy conferences on cybernetics had ended (Boden 2006; McCorduck 1972). The two movements coexisted for roughly a de- cade, but by the mid-1960s, the proponents of symbolic ai gained control of national funding conduits and ruthlessly defunded cybernetics research. This effectively liquidated the subfields of self-organizing systems, neural networks and adaptive machines, evolutionary programming, biological computation, and bionics for several decades, leaving the workers in management, therapy and the social sciences to carry the torch. i think some of the polemical pushing-and-shoving between first-order control theorists and second-order crowds that i witnessed in subsequent decades was the cumulative result of a shift of funding, membership, and research from the "hard" natural sciences to "soft" socio-psychological interventions.

- ^ a b Jean-Pierre Dupuy, "The autonomy of social reality: on the contribution of systems theory to the theory of society" in: Elias L. Khalil & Kenneth E. Boulding eds., Evolution, Order and Complexity, 1986.

- ^ Peter Harries-Jones (1988), "The Self-Organizing Polity: An Epistemological Analysis of Political Life by Laurent Dobuzinskis" in: Canadian Journal of Political Science (Revue canadienne de science politique), Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 431-433.

- ^ a b c Kenneth D. Bailey (1994), Sociology and the New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis, p.163.

- ^ Feinstein, C.H. (September 1969). Socialism, Capitalism and Economic Growth: Essays Presented to Maurice Dobb. Cambridge University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-0521049870.

At some future date it may appear as a joke of history that socialist countries learned at long last to overcome their prejudices and to dismantle clumsy planning mechanisms in favour of more effective market elements just at a time when the rise of computers and of cybernetics laid the foundation for greater opportunities in comprehensive planning.

- ^ Allin Cottrell & W.Paul Cockshott, Towards a new socialism (Nottingham, England: Spokesman, 1993). Retrieved: 17 March 2012.

- ^ Note: this does not refer to the concept of Racial Memory but to the concept of cumulative adaptation to a particular niche, such as the case of the pepper moth having genes for both light and dark environments.

- ^ "Why Physics Is Not a Discipline - Issue 35: Boundaries - Nautilus". Nautilus. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- ^ McClelland, Kent A., and Thomas J. Fararo (Eds.). 2006. Purpose, Meaning, and Action: Control Systems Theories in Sociology. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ "SSCC (Sinai Sustainability Cybernetics Center)". MIT Enterprise Forum, Pan Arab Region.

- ^ "SSCC (Sinai Sustainability Cybernetics Center)" the 46th team to qualify for this year's MIT semi-finalist round — Naharnet. Naharnet.com (2013-04-25). Retrieved on 2013-11-02.

- ^ "SSCC, One minute movie".

- ^ "TV Interview on the project(Arabic)".

- ^ "CYSP I, the first cybernetic sculpture of art's history". Leonardo/OLATS - Observatoire Leonardo des arts et des technosciences.

- ^ Bruce Clarke and Linda Dalrymple Henderson, ed. (2002). From Energy to Information: Representation in Science, Technology, Art, and Literature. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 255–277.

- ^ Ascott, Roy (2003). Edward A. Shanken (ed.). Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology, and Consciousness. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Schellnhuber, H.-J., Discourse: Earth system analysis - The scope of the challenge, pp. 3-195. In: Schellnhuber, H.-J. and Wenzel, V. (Eds.). 1998. Earth system analysis: Integrating science for sustainability. Berlin: Springer.

- ^ Schellnhuber, H.-J., Earth system analysis and the second Copernican revolution. Nature, 402, C19-C23. 1999.

Further reading

- Medina, Eden (2011). Cybernetic revolutionaries : technology and politics in Allende's Chile. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-01649-0.

- Pickering, Andrew (2010). The cybernetic brain : sketches of another future ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226667898.

- Gerovitch, Slava (2002). From newspeak to cyberspeak : a history of Soviet cybernetics. Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.]: MIT Press. ISBN 0262-07232-7.

- Johnston, John (2008). The allure of machinic life : cybernetics, artificial life, and the new AI. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-10126-4.

- Heikki Hyötyniemi (2006). Neocybernetics in Biological Systems. Espoo: Helsinki University of Technology, Control Engineering Laboratory.

- Francis Heylighen, and Cliff Joslyn (2002). "Cybernetics and Second Order Cybernetics", in: R.A. Meyers (ed.), Encyclopedia of Physical Science & Technology (3rd ed.), Vol. 4, (Academic Press, San Diego), p. 155-169.

- Charles François (1999). "Systemics and cybernetics in a historical perspective". In: Systems Research and Behavioral Science. Vol 16, pp. 203–219 (1999)

- Heinz von Foerster, (1995), Ethics and Second-Order Cybernetics.

- Heims, Steve Joshua (1993). Constructing a social science for postwar America : the cybernetics group, 1946-1953 (1st ed.). Cambridge, Mass. u.a.: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262581233.

- Pangaro, Paul. "Cybernetics - A Definition".

- Stuart Umpleby (1989), "The science of cybernetics and the cybernetics of science", in: Cybernetics and Systems", Vol. 21, No. 1, (1990), pp. 109–121.

- Arbib, Michael A. (1987). Brains, machines, and mathematics (2nd ed.). New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387965390.

- Patten, Bernard C.; Odum, Eugene P. (December 1981). "The Cybernetic Nature of Ecosystems". The American Naturalist. 118 (6). The University of Chicago Press: 886–895. doi:10.1086/283881. JSTOR 2460822?.

- Hans Joachim Ilgauds (1980), Norbert Wiener, Leipzig.

- Beer, Stafford (1974). Designing freedom. Chichester, West Sussex, England: Wiley. ISBN 978-0471951650.

- Pask, Gordon (1972). "Cybernetics". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Helvey, T.C. (1971). The age of information; an interdisciplinary survey of cybernetics. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Educational Technology Publications. ISBN 9780877780083.

- Roy Ascott (1967). Behaviourist Art and the Cybernetic Vision. Cybernetica, Journal of the International Association for Cybernetics (Namur), 10, pp. 25–56

- William Ross Ashby (1956). An introduction to cybernetics (PDF). Chapman & Hall. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- Norbert Wiener (1948). Hermann & Cie (ed.). Cybernetics; or, Control and communication in the animal and the machine. Paris: Technology Press. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- Arbib, Michael A. (1972). The Metaphorical Brain. Wiley. ISBN 0-471-03249-2.

- F. H. George (1971). Cybernetics. Teach Yourself Books. ISBN 0-340-05941-9.

- V. Pekelis (1974). Cybernetics A to Z. Moscow: Mir Publishers.

External links

- General

- Norbert Wiener and Stefan Odobleja - A Comparative Analysis

- Reading List for Cybernetics

- Principia Cybernetica Web

- Web Dictionary of Cybernetics and Systems

- Glossary Slideshow (136 slides)

- "Basics of Cybernetics". Archived from the original on 2010-08-11. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- What is Cybernetics? Livas short introductory videos on YouTube

- Music

- Mailman, Joshua B. 2012. "Seven Metaphors for (Music) Listening: DRAMaTIC" in Journal of Sonic Studies v.2.

- Societies