Millennials in the United States

| Part of a series on |

| Social generations of the Western world |

|---|

|

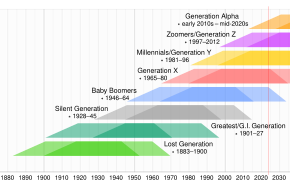

Millennials, also known as Generation Y or Gen Y, are the demographic cohort following Generation X and preceding Generation Z.

Unlike their counterparts in most other developed nations, Millennials in the United States are a relatively large cohort in their nation's population, which has implications for their nation's economy and geopolitics.[1] They generally adopt a slow-life history strategy in that compared to previous cohorts, they tend to be highly educated, be less inclined to engage in sexual intercourse, marry later, and have fewer children, or none at all.[2] Furthermore, Millennials are much less religious than older generations,[3][4][5] though some still identify as spiritual.[6] Millennials have faced economic challenges posed by the Great Recession, and another one in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[7] But they have been steadily catching up with their elders in terms of inflation-adjusted median household income and home ownership.[2][8] They also maintain a high level of participation in the labor force.[9]

Millennials are sometimes known as digital natives because they came of age when the Internet, electronic devices, and social media entered widespread usage.[10]

Despite their reputation for holding left-wing views, Millennials are not consistently aligned with liberalism.[11][12][13] In fact, they frequently identify as politically independent[13] and are not idealists.[11] Polling agency Ipsos-MORI warned that "many of the claims made about millennial characteristics are simplified, misinterpreted or just plain wrong, which can mean real differences get lost" and that "[e]qually important are the similarities between other generations—the attitudes and behaviors that are staying the same are sometimes just as important and surprising."[14]

Terminology and etymology

[edit]Authors William Strauss and Neil Howe, who created the Strauss–Howe generational theory, coined the term 'millennial' in 1987.[15][16] because the oldest members of this demographic cohort came of age at around the turn of the third millennium A.D.[17] They wrote about the cohort in their books Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069 (1991)[18] and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000).[15]

In August 1993, an Advertising Age editorial coined the phrase Generation Y to describe teenagers of the day, then aged 13–19 (born 1974–1980), who were at the time defined as different from Generation X.[19] However, the 1974–1980 cohort was later re-identified by most media sources as the last wave of Generation X,[20] and by 2003 Ad Age had moved their Generation Y starting year up to 1982.[21] According to journalist Bruce Horovitz, in 2012, Ad Age "threw in the towel by conceding that millennials is a better name than Gen Y,"[16] and by 2014, a past director of data strategy at Ad Age said to NPR "the Generation Y label was a placeholder until we found out more about them."[22]

Millennials are sometimes called echo boomers, due to them often being the offspring of the baby boomers, the significant increase in birth rates from the early 1980s to mid-1990s, and their generation's large size relative to that of boomers.[23][24][25][26] In the United States, the echo boom's birth rates peaked in August 1990[27][23] and a twentieth-century trend toward smaller families in developed countries continued.[28][29] Psychologist Jean Twenge described millennials as "Generation Me" in her 2006 book Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans Are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – and More Miserable Than Ever Before,[30][31] while in 2013, Time magazine ran a cover story titled Millennials: The Me Me Me Generation.[32] Alternative names for this group proposed include the Net Generation,[33] Generation 9/11,[34] Generation Next,[35] and The Burnout Generation.[36]

American sociologist Kathleen Shaputis labeled millennials as the Boomerang Generation or Peter Pan Generation because of the members' perceived tendency for delaying some rites of passage into adulthood for longer periods than most generations before them. These labels were also a reference to a trend toward members living with their parents for longer periods than previous generations.[37] Kimberly Palmer regards the high cost of housing and higher education, and the relative affluence of older generations, as among the factors driving the trend.[38] Questions regarding a clear definition of what it means to be an adult also impact a debate about delayed transitions into adulthood and the emergence of a new life stage, Emerging Adulthood. A 2012 study by professors at Brigham Young University found that college students were more likely to define "adult" based on certain personal abilities and characteristics rather than more traditional "rite of passage" events.[39] Larry Nelson noted that "In prior generations, you get married and you start a career and you do that immediately. What young people today are seeing is that approach has led to divorces, to people unhappy with their careers … The majority want to get married […] they just want to do it right the first time, the same thing with their careers."[39]

Date and age range definitions

[edit]Oxford Living Dictionaries describes a millennial as a person "born between the early 1980s and the late 1990s."[40] Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines millennial as "a person born in the 1980s or 1990s."[41]

Jonathan Rauch, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote for The Economist in 2018 that "generations are squishy concepts", but the 1981 to 1996 birth cohort is a "widely accepted" definition for millennials.[42] Reuters also state that the "widely accepted definition" is 1981–1996.[43]

Although the United States Census Bureau have said that "there is no official start and end date for when millennials were born"[44] and they do not officially define millennials,[45] a U.S. Census publication in 2022 noted that Millennials are "colloquially defined as" the cohort born from 1981 to 1996, using this definition in a breakdown of Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data.[46] The Pew Research Center defines millennials as born from 1981 to 1996, choosing these dates for "key political, economic and social factors", including the September 11 terrorist attacks, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Great Recession, and Internet explosion.[47][48] The United States Library of Congress explains that "defining generations is not an exact science" however cites Pew’s 1981-1996 definition to define millennials.[49] Various media outlets and statistical organizations have cited Pew's definition including The Washington Post,[50] The New York Times,[51] The Wall Street Journal,[52] PBS,[53] The Los Angeles Times,[54] and the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics.[55] The Brookings Institution defines the millennial generation as those born from 1981 to 1996,[56] as does Gallup,[57] Federal Reserve Board,[58] American Psychological Association,[59] and CBS.[60]

Psychologist Jean Twenge defines millennials as those born 1980–1994.[61] CNN reports that studies often use 1981–1996 to define millennials, but sometimes list 1980–2000.[62] Sociologist Elwood Carlson, who calls the generation "New Boomers", identified the birth years of 1983–2001, based on the upswing in births after 1983 and finishing with the "political and social challenges" that occurred after the 9/11 terrorist acts.[63] Author Neil Howe defines millennials as being born from 1982 to 2004 in his most recent book, The Fourth Turning is Here.[64]

The cohorts born during the cusp years before and after millennials have been identified as "microgenerations" with characteristics of both generations. Names given to these cuspers include Xennials,[65] Generation Catalano,[66] the Oregon Trail Generation;[67] Zennials,[68] and Zillennials,[69] respectively.

Cognitive abilities

[edit]Intelligence researcher James R. Flynn discovered that back in the 1950s, the gap between the vocabulary levels of adults and children was much smaller than it is in the early twenty-first century. Between 1953 and 2006, adult gains on the vocabulary subtest of the Wechsler IQ test were 17.4 points whereas the corresponding gains for children were only 4. He asserted that some of the reasons for this are the surge in interest in higher education and cultural changes. The number of Americans pursuing tertiary qualifications and cognitively demanding jobs has risen significantly since the 1950s. This boosted the level of vocabulary among adults. Back in the 1950s, children generally imitated their parents and adopted their vocabulary. This was no longer the case in the 2000s, when teenagers often developed their own subculture and as such were less likely to use adult-level vocabulary on their essays.[70]

Psychologists Jean Twenge, W. Keith Campbell, and Ryne A. Sherman analyzed vocabulary test scores on the U.S. General Social Survey () and found that after correcting for education, the use of sophisticated vocabulary has declined between the mid-1970s and the mid-2010s across all levels of education, from below high school to graduate school. Those with at least a bachelor's degree saw the steepest decline. Hence, the gap between people who never received a high-school diploma and a university graduate has shrunk from an average of 3.4 correct answers in the mid- to late-1970s to 2.9 in the early- to mid-2010s. Higher education offers little to no benefits to verbal ability. Because those with only a moderate level of vocabulary were more likely to be admitted to university than in the past, the average for degree holders declined. There are various explanations for this. Accepting high levels of immigrants, many of whom not particularly proficient in the English language, could lower the national adult average. Young people nowadays are much less likely to read for pleasure, thus reducing their levels of vocabulary. On the other hand, while the College Board has reported that SAT verbal scores were on the decline, these scores are an imperfect measure of the vocabulary level of the nation as a whole because the test-taking demographic has changed and because more students take the SAT in the 2010s then in the 1970s, which means there are more with limited ability who took it. Population aging is unconvincing because the effect is too weak.[71]

Common culture

[edit]

Millennials grew up during the 1990s, a time of peace, prosperity, and predictability that followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.[72] Many White Millennials were raised by helicopter parents, but this was not a common experience among other Millennials in the United States.[73] As adults, Millennials expect the institutions to look after their well-being.[64] They tend to follow a slow life history strategy,[2] preferring deep and cooperative relationships, including with their employers.[64] Culturally, they found themselves gravitated towards apathy, irony (as seen in the 1996 song "Ironic" by Alanis Morissette), and sentimentality (represented by the music performed by Britney Spears).[72] Millennial humor, a major feature of Internet memes during the 2010s, contained elements of absurdism and surrealism.[74] Surveys of high-school seniors and college freshmen of the early 2010s found that the proportion of students who placed a high value on wealth and who did not think it was important to keep abreast of political affairs grew, while the number of those who thought it was necessary to develop "a meaningful philosophy of life" fell compared to older generations. Compared to Baby Boomers, Millennials were also less likely to be involved in an environmental cleanup effort.[75]

Experts disagree on whether or not the level of narcissism, as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI), has gone up among Millennials relative to other cohorts.[76][77][78] In any case, there is considerable evidence for Millennials being a highly self-focused cohort as American society at large continues to shift towards individualism, a trend observed in every generation born after the Second World War. Phrases such as "believe in yourself" or "just be yourself" appeared with growing frequencies among popular books published during the formative years of Millennials.[2] In 2015, the Pew Research Center conducted research regarding generational identity that said a majority of millennials surveyed did not like the "millennial" label.[79] It was discovered that millennials are less likely to strongly identify with the generational term when compared to Generation X or the baby boomers, with only 40% of those born between 1981 and 1997 identifying as millennials. Among older millennials, those born 1981–1988, Pew Research found that 43% personally identified as members of the older demographic cohort, Generation X, while only 35% identified as millennials. Among younger millennials (born 1989–1997), generational identity was not much stronger, with only 45% personally identifying as millennials. It was also found that millennials chose most often to define themselves with more negative terms such as self-absorbed, wasteful, or greedy.[79] On the other hand, since the 2000 U.S. Census, millennials have taken advantage of the possibility of selecting more than one racial group in abundance.[80][81]

Among Millennials who played computer games, Oregon Trail II and Super Mario Bros. were among the most popular choices.[2] Television programs such as Dawson's Creek (1998–2003) and Glee (2009–2015) appealed to broad segments of the Millennial cohort when they first aired. Tops songs during period had lyrics emphasizing the level of individualism among Millennials. "I am the greatest man that ever lived," declared the band Weezer. "Don't cha wish your girlfriend was hot like me?" asked the Pussycat Dolls.[2] A 2019 poll by Ypulse found that among people aged 27 to 37, the musicians most representative of their generation were Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, the Backstreet Boys, Michael Jackson, Drake, and Eminem. (The last two were tied in fifth place.)[82]

A 2007 report by the National Endowment of the Arts stated that Americans aged 15 to 24 spent an average of two hours watching television and only seven minutes on reading. Reading comprehension skills of American adults of all levels of education deteriorated between the early 1990s and the early 2000s, especially among those with advanced degrees. According to employers, almost three quarters of university graduates were "deficient" in English writing skills. Meanwhile, the reading scores of American tenth-graders proved mediocre, in fifteenth place out of 31 industrialized nations, and the number of twelfth-graders who had never read for pleasure doubled to 19%.[83] Publishers and booksellers observed that the sales of adolescent and young-adult fiction remained strong. Part of the reason is because older adults were buying titles intended for younger people, which inflated the market, and because there were fewer readers buying more books.[83]

By the late 2010s, viewership of late-night American television among adults aged 18 to 49, the most important demographic group for advertisers, has fallen substantially despite an abundance of materials. This is due in part to the availability and popularity of streaming services. However, when delayed viewing within three days is taken into account, the top shows all saw their viewership numbers boosted.[84] Despite having the reputation for "killing" many things of value to the older generations, millennials and Generation Z are nostalgically preserving Polaroid cameras, vinyl records, needlepoint, and home gardening, to name just some.[85] In fact, Millennials are a key cohort behind the vinyl revival.[86] However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s, certain items whose futures were in doubt due to a general lack of interest by millennials appear to be reviving with stronger sales than in previous years, such as canned food.[87]

Millennial fans, especially girls and women, have been the key factor behind the commercial success of franchises such as Harry Potter, Twilight, and The Hunger Games. More recently, they came out in large numbers for the movie Barbie (2023) and Taylor Swift's Eras Tour.[88]

Demographics

[edit]

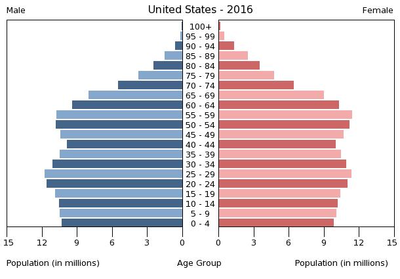

Baby Boomers came of age during a time of reliable contraception and legal abortion. Accordingly, those who had children wanted and planned their families, and these were generally smaller than for previous cohorts.[2] As of the mid-2010s, the United States is one of the few developed countries that does not have a top-heavy population pyramid. In fact, as of 2016, the median age of the U.S. population was younger than that of all other rich nations except Australia, New Zealand, Cyprus, Ireland, and Iceland, whose combined population is only a fraction of the United States. This is because American baby boomers had a higher fertility rate compared to their counterparts from much of the developed world. Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, and South Korea are all aging rapidly by comparison because their millennials are smaller in number than their parents. This demographic reality puts the United States at an advantage compared to many other major economies as the millennials reach middle age: the nation will still have a significant number of consumers, investors, and taxpayers.[1]

Millennial population size varies, depending on the definition used. Using its own definition, the Pew Research Center estimated that millennials comprised 27% of the U.S. population in 2014.[89] In the same year, using dates ranging from 1982 to 2004, Neil Howe revised the number to over 95 million people in the U.S.[90] In a 2012 Time magazine article, it was estimated that there were approximately 80 million U.S. millennials.[91] The United States Census Bureau, using birth dates ranging from 1982 to 2000, stated the estimated number of U.S. millennials in 2015 was 83.1 million people.[92]

In 2017, fewer than 56% millennial were non-Hispanic whites, compared with more than 84% of Americans in their 70s and 80s, 57% had never been married, and 67% lived in a metropolitan area.[93] According to the Brookings Institution, millennials are the “demographic bridge between the largely white older generations (pre-millennials) and much more racially diverse younger generations (post-millennials).”[94]

By analyzing data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the Pew Research Center estimated that millennials, whom they define as people born between 1981 and 1996, outnumbered baby boomers, born from 1946 to 1964, for the first time in 2019. That year, there were 72.1 million millennials compared to 71.6 million baby boomers, who had previously been the largest living adult generation in the country. Data from the National Center for Health Statistics shows that about 62 million millennials were born in the United States, compared to 55 million members of Generation X, 76 million baby boomers, and 47 million from the Silent Generation. Between 1981 and 1996, an average of 3.9 million millennial babies were born each year, compared to 3.4 million average Generation X births per year between 1965 and 1980. But millennials continue to grow in numbers as a result of immigration and naturalization. In fact, millennials form the largest group of immigrants to the United States in the 2010s. Pew projected that the millennial generation would reach around 74.9 million in 2033, after which mortality would outweigh immigration.[95] Yet 2020 would be the first time millennials (who are between the ages of 24 and 39) find their share of the electorate shrink as the leading wave of Generation Z (aged 18 to 23) became eligible to vote. In other words, their electoral power peaked in 2016. In absolute terms, however, the number of foreign-born millennials continues to increase as they become naturalized citizens. In fact, 10% of American voters were born outside the country by the 2020 election, up from 6% in 2000. The fact that people from different racial or age groups vote differently means that this demographic change will influence the future of the American political landscape. While younger voters hold significantly different views from their elders, they are considerably less likely to vote. Non-whites tend to favor candidates from the Democratic Party while whites by and large prefer the Republican Party.[96]

According to the Pew Research Center, "Among men, only 4% of millennials [ages 21 to 36 in 2017] are veterans, compared with 47%" of men in their 70s and 80s, "many of whom came of age during the Korean War and its aftermath."[93] Some of these former military service members are combat veterans, having fought in Afghanistan and/or Iraq.[97] As of 2016, millennials are the majority of the total veteran population.[98] According to the Pentagon in 2016, 19% of Millennials are interested in serving in the military, and 15% have a parent with a history of military service.[99]

Economic prospects and trends

[edit]Employment and finances

[edit]

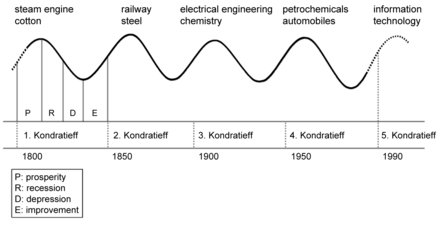

The oldest Millennials were young adults at the time of the Great Recession of the late 2000s, and this event has severely damaged their ability to generate and accumulate wealth.[101] Youth unemployment soared during the Great Recession, reaching a record 19% in July 2010.[102] Underemployment was also a major factor. Many Millennials found themselves struggling to make ends meet and were commonly living with their parents.[103] In April 2012, it was reported that half of all new college graduates in the US were still either unemployed or underemployed.[104] According to a Bloomberg L.P., "Three and a half years after the worst recession since the Great Depression, the earnings and employment gap between those in the under-35 population and their parents and grandparents threatens to unravel the American dream of each generation doing better than the last. The nation's younger workers have benefited least from an economic recovery that has been the most uneven in recent history."[105] Despite higher college attendance rates than Generation X, many Millennials were stuck in low-paid jobs, with the percentage of degree-educated young adults working in low-wage industries rising from 23% to 33% between 2000 and 2014.[106] Not only did they receive lower wages, they also had to work longer hours for fewer benefits.[7] By the mid-2010s, the U.S. economy was well on its way towards becoming a highly dynamic and increasingly service-oriented system, with careers getting replaced by short-term full-time jobs, full-time jobs by part-time positions, and part-time positions by income-generating hobbies. In one important way the economic prospects of Millennials are similar to those of their parents the Baby Boomers: their huge number means that the competition for jobs was always going to be intense.[1][107]

Yet despite all the hardship they have had to endure, they still have remained optimistic, as shown when about nine out of ten millennials surveyed by the Pew Research Center said that they currently have enough money or that they will eventually reach their long-term financial goals.[108] But many Millennials were concerned they were not saving enough for retirement thanks to expensive housing and student debts, among other reasons.[109] Risk management specialist and business economist Olivia S. Mitchell of the University of Pennsylvania calculated that in order to retire at 50% of their last salary before retirement, millennials will have to save 40% of their incomes for 30 years. She told CNBC, "Benefits from Social Security are 76% higher if you claim at age 70 versus 62, which can substitute for a lot of extra savings." Maintaining a healthy lifestyle—avoiding smoking, over-drinking, and sleep deprivation—should prove beneficial.[110]

By late 2010s, however, Millennials were steadily closing the wealth gap between them and older generations.[8] Much of this progress has been due to rising wages earned by young women.[2] After adjusting for inflation, the median household income of Millennials exceeded those of Generation X and the Baby Boomers when they were at the same age. In terms of wealth (assets minus debts), student loan debt was a major problem for Millennials, however, though those with four-year degrees were out-earning their peers without higher education.[2] Millennials enjoy a number of important advantages compared to their elders, such as higher levels of education, and longer working lives, but they suffer some disadvantages including limited prospects of economic growth, leading to delayed home ownership.[112] In addition, Millennials have a higher labor participate rate than other adults.[9] Because they are having fewer children than older generations or none at all, Millennial households have more money to spend per person, which has helped them accumulate more wealth.[2] As consumers, Millennials and Generation Z are more likely than older cohorts to prioritize personal well-being and happiness, and they are willing to spend on hobbies and other non-essential items.[113]

Even though Millennials are well known for taking out large amounts of student loans, these are actually not their main source of non-mortgage personal debt, but rather credit-card debt. According to a 2019 Harris poll, the average non-mortgage personal debt of millennials was US$27,900, with credit card debt representing the top source at 25%.[111] Although it is often said that millennials ignore conventional advertising, they are in fact heavily influenced by it. They are particularly sensitive to appeals to transparency, to experiences rather than things, and flexibility.[114]

As they saw their economic prospects improved in the aftermath of the Great Recession, the COVID-19 global pandemic hit, forcing lock-down measures that resulted in an enormous number of people losing their jobs. For Millennials, this is the second major economic downturn in their adult lives so far.[7] However, by early 2022, as the pandemic waned, workers aged 25 to 64 were returning to the work force at a steady pace. According to The Economist, if the trend continued, then their work-force participation would return to the pre-pandemic level of 83% by the end of 2022.[115] Millennials and Generation Z have been responsible for a surge in U.S. labor participation rates in the 2010s and 2020s.[116] Even so, the U.S. economy would continue to face labor shortages, which puts workers at an advantage while contributing to inflation.[115]

Working and volunteering

[edit]

Millennials prefer to work for companies engaged in the betterment of society.[117] Majorities are willing to take a pay cut to pursue a career path aligned with their passions and values.[117] They have been as troublesome to deal with by employers.[118][119] They have great expectations for advancement, salary, benefits, and for a coaching relationship with their manager,[119][120][121][122] and frequently switch jobs as a result.[123] They are also more likely to value a "work-life balance" than older cohorts.[121][124]

Data also suggests millennials are highly interested in volunteering.[124] Volunteering activities between 2007 and 2008 show the millennial age group experienced almost three-times the increase of the overall population, which is consistent with a survey of 130 college upperclassmen depicting an emphasis on altruism in their upbringing.[124]

Housing

[edit]Millennials were steadily leaving rural counties for urban areas for lifestyle and economic reasons in the early 2010s.[125] At that time, they were responsible for the so-called "back-to-the-city" trend.[126] Many urban areas in different parts of the United States grew considerably as a result.[127] Mini-apartments became more and more common in major urban areas with among young people living alone, who are willing to give up space in exchange for living in a location they liked.[128] Data from the Census Bureau reveals that in 2018, 34% of American adults below the age of 35 owned a home, compared to the national average of almost 64%.[129]

As they accumulated wealth, Millennials were becoming homeowners at a pace close to those of the Baby Boomers and Generation X when they were at the same age.[2] U.S. Census data shows that following the Great Recession, American suburbs grew faster than dense urban cores thanks to Millennial homeowners relocating to the suburbs.[131] This trend will likely continue as more and more Millennials purchase a home.[132] Economic recovery and easily obtained mortgages help explain this phenomenon.[131] Exurbs have been receiving attention from Millennial home buyers as well.[133] Among Baby Boomers who have retired, a significant portion opts to live in the suburbs, where the Millennials are also moving to in large numbers as they have children of their own. These confluent trends increase the level of economic activities in the American suburbs.[134] On the other hand, some Millennials prefer the slower pace of life and lower costs of living in rural places. While rural America lacked the occupational variety offered by urban America, multiple rural counties can still match one major city in terms of economic opportunities.[135]

While 14% of the U.S. population relocate at least once each year, Americans in their 20s and 30s are more likely to move than retirees.[136] As the majority of Millennials reach their 30s and 40s, they become the largest group home buyers.[101] People leaving the big cities generally look for places with low cost of living, including housing costs, warmer climates, lower taxes, better economic opportunities, and better school districts for their children.[136][137][138] High taxes and high cost of living are also reasons why people are leaving entire states behind.[138][139] For example, a 2019 poll by Edelman Intelligence of 1,900 residents of California found that 63% of Millennials said they were thinking about leaving the Golden State and 55% said they wanted to do so within five years. Popular destinations include Oregon, Nevada, Arizona, and Texas, according to California's Legislative Analyst's Office.[139] Broadly speaking, among younger cohorts of home owners, the Millennials were migrating North while Generation Z was going South.[140] Economics of space is also important, now that it has become much easier to transmit information and that e-commerce and delivery services have contracted perceived distances.[133] Even Millennials who do not have children prefer homes with plenty of space, so that the extra rooms can be turned into an office, a place for their hobbies, or a bedroom for an aging parent.[141]

Places in the South and Southwestern United States are especially popular. In some communities, millennials and their children are moving in so quickly that schools and roads are becoming overcrowded. This rising demand pushes prices upwards, making affordable housing options less plentiful.[126] Entry-level homes, which almost ceased to exist after housing bubble busted in the 2000s, started to return in numbers as builders respond to rising demand from Millennials. In order to cut construction costs, builders offer few to no options for floor plans. Previously, the Great Recession forced millennials delay home ownership. But by the late 2010s, older millennials had accumulated sufficient savings and were ready to buy a home. Prices have risen in the late 2010s due to high demand, but this could incentivize more companies to enter the business of building affordable homes.[142] Historically, between the 1950s and 1980s, Americans left the cities for the suburbs because of crime. Suburban growth slowed because of the Great Recession but picked up pace afterwards.[131] Overall, American cities with the largest net losses in their Millennial populations were New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, while those with the top net gains were Houston, Denver, and Dallas.[143]

As a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, interest in suburban properties skyrocketed, with Millennials being the largest block of buyers. For this reason, the home-building industry was seeing better recovery than expected.[144] As Millennials and senior citizens increasingly demand affordable housing outside the major cities, to prevent another housing bubble, banks and regulators have restricted lending to filter out speculators and those with bad credit.[145] By the time they neared midlife in the early 2020s, the bulk of older Millennials had entered the housing market, the number of millennial homeowners has grown substantially between the late 2010s and the early 2020s, so much so that by 2022, home-owning millennials outnumbered their renting counterparts for the first time.[146] Millennials working remotely were especially interested in suburban life.[130] Despite their ethnic diversity, younger Millennials appear to prefer homogeneous neighborhoods.[147] They are also more likely to prefer neighbors who share their political views compared to older cohorts and to Generation Z.[148]

Education

[edit]General trends

[edit]

According to the Pew Research Center, 53% of American millennials attended or were enrolled in university in 2002.[149] By the early 2020s, 39% of millennials had at least a bachelor's degree, more than the Baby Boomers at 25%.[150] Historically, university students were more likely to be male than female. But the late 2010s, the situation has reversed. Women are now more likely to enroll in university than men. In 2018, upwards of one third of each sex is a university student.[151]

In the United States today, high school students are generally encouraged to attend college or university after graduation while the options of technical school and vocational training are often neglected.[152] Historically, high schools separated students on career tracks, but all this changed in the late 1980s and early 1990s thanks to a major effort in the large cities to provide more abstract academic education to everybody. The mission of high schools became preparing students for college.[153] However, this program faltered in the 2010s, as institutions of higher education came under heightened skepticism due to high costs and disappointing results. People became increasingly concerned about debts and deficits. No longer were promises of educating "citizens of the world" or estimates of economic impact coming from abstruse calculations convincing. Colleges and universities found it necessary to prove their worth by clarifying how much money from which industry and company funded research, and how much it would cost to attend.[154] According to the U.S. Department of Education, people with technical or vocational trainings are slightly more likely to be employed than those with a bachelor's degree and significantly more likely to be employed in their fields of specialty.[152] The United States currently suffers from a shortage of skilled tradespeople.[152] Because jobs (that suited what one studied) were so difficult to find in the few years following the Great Recession, the value of getting a liberal arts degree and studying the humanities at an American university came into question, their ability to develop a well-rounded and broad-minded individual notwithstanding.[155] Those who majored in the humanities and the liberal arts in the 2010s were most likely to regret having done so, whereas those in STEM, especially computer science and engineering, were the least likely.[156] As of 2019, the total college debt has exceeded US$1.5 trillion, and two out of three college graduates are saddled with debt.[149] The average borrower owes US$37,000, up US$10,000 from ten years before. A 2019 survey by TD Ameritrade found that over 18% of millennials (and 30% of Generation Z) said they have considered taking a gap year between high school and college.[157]

In 2019, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published research (using data from the 2016 Survey of Consumer Finances) demonstrating that after controlling for race and age cohort families with heads of household with post-secondary education who were born before 1980 there have been wealth and income premiums, while for families with heads of household with post-secondary education but born after 1980 the wealth premium has weakened to point of statistical insignificance (in part because of the rising cost of college) and the income premium while remaining positive has declined to historic lows (with more pronounced downward trajectories with heads of household with postgraduate degrees).[158] Quantitative historian Peter Turchin noted that the United States was overproducing university graduates in the 2000s and predicted, using historical trends, that this would be one of the causes of political instability in the 2020s, alongside income inequality, stagnating or declining real wages, growing public debt. According to Turchin, intensifying competition among graduates, whose numbers were larger than what the economy could absorb, leads to political polarization, social fragmentation, and even violence as many become disgruntled with their dim prospects despite having attained a high level of education. He warned that the turbulent 1960s and 1970s could return, as having a massive young population with university degrees was one of the key reasons for the instability of the past.[159]

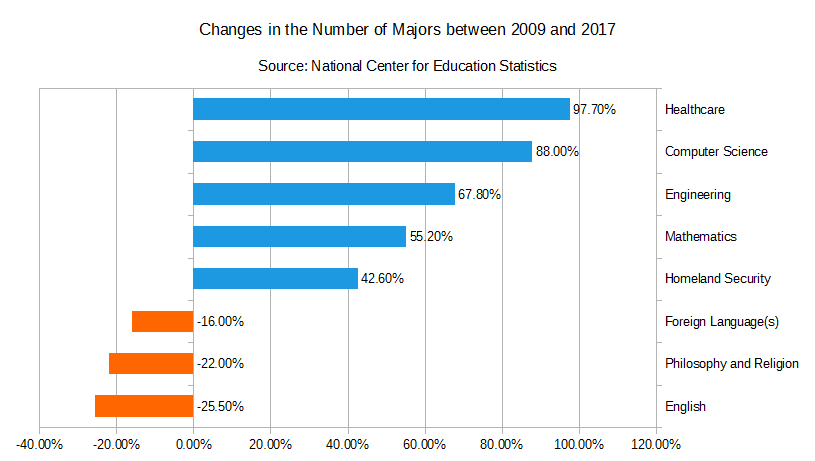

According to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, students were turning away from liberal arts programs. Between 2012 and 2015, the number of graduates in the humanities dropped from 234,737 to 212,512. Consequently, many schools have relinquished these subjects, dismissed faculty members, or closed completely.[160] Data from the National Center for Education Statistics revealed that between 2008 and 2017, the number of people majoring in English plummeted by just over a quarter. At the same time, those in philosophy and religion fell 22% and those who studied foreign languages dropped 16%. Meanwhile, the number of university students majoring in homeland security, science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM), and healthcare skyrocketed. (See figure below.)[161]

Despite the fact that educators and political leaders, such as President Barack Obama, have been trying to years to improve the quality of STEM education in the United States, and that various polls have demonstrated that more students are interested in these subjects, many fail to earn a university degree in STEM.[162] According to The Atlantic, 48% of students majoring in STEM dropped out of their programs between 2003 and 2009.[163] Data collected by the University of California, Los Angeles, (UCLA) in 2011 showed that although these students typically came in with excellent high school GPAs and SAT scores, among science and engineering students, including pre-medical students, 60% changed their majors or failed to graduate, twice the attrition rate of all other majors combined. Despite their initial interest in secondary school, many university students find themselves overwhelmed by the reality of a rigorous STEM education.[162] Some are mathematically unskilled,[162][163] while others are simply lazy.[162] The National Science Board raised the alarm all the way back in the mid-1980s that students often forget why they wanted to be scientists and engineers in the first place. Many bright students had an easy time in high school and failed to develop good study habits. In contrast, Chinese, Indian, and Singaporean students are exposed to mathematics and science at a high level from a young age.[162] Moreover, according education experts, many mathematics schoolteachers were not as well-versed in their subjects as they should be, and might well be uncomfortable with mathematics.[163] Given two students who are equally prepared, the one who goes to a more prestigious university is less likely to graduate with a STEM degree than the one who attends a less difficult school. Competition can defeat even the top students. Meanwhile, grade inflation is a real phenomenon in the humanities, giving students an attractive alternative if their STEM ambitions prove too difficult to achieve. Whereas STEM classes build on top of each other—one has to master the subject matter before moving to the next course—and have black and white answers, this is not the case in the humanities, where things are a lot less clear-cut.[162]

In 2015, educational psychologist Jonathan Wai analyzed average test scores from the Army General Classification Test in 1946 (10,000 students), the Selective Service College Qualification Test in 1952 (38,420), Project Talent in the early 1970s (400,000), the Graduate Record Examination between 2002 and 2005 (over 1.2 million), and the SAT Math and Verbal in 2014 (1.6 million). Wai identified one consistent pattern: those with the highest test scores tended to pick the physical sciences and engineering as their majors while those with the lowest were more likely to choose education. (See figure below.)[164][165]

During the 2010s, the mental health of American graduate students in general was in a state of crisis.[166]

Knowledge of history

[edit]A February 2018 survey of 1,350 individuals found that 66% of the American millennials (and 41% of all U.S. adults) surveyed did not know what Auschwitz was,[167] while 41% incorrectly claimed that two million Jews or fewer were killed during the Holocaust, and 22% said that they had never heard of the Holocaust.[168] Over 95% of American millennials were unaware that a portion of the Holocaust occurred in the Baltic states, which lost over 90% of their pre-war Jewish population, and 49% were not able to name a single Nazi concentration camp or ghetto in German-occupied Europe.[169][170] However, at least 93% surveyed believed that teaching about the Holocaust in school is important and 96% believed the Holocaust happened.[171]

The YouGov survey found that 42% of American millennials have never heard of Mao Zedong and another 40% are unfamiliar with Che Guevara.[172][173]

Health and welfare

[edit]Teenage pregnancy

[edit]

Teenage pregnancy rates in the United States have been falling steadily since the 1990s.[174]

Mental health

[edit]Although Millennials generally had a happy time growing up in the 1990s and 2000s, as adults, their mental health was in a state of crisis. During the 2010s, many succumbed to "deaths of despair"—notably, drug overdose, alcoholic liver disease, and suicide. During the late 2010s, and before the COVID-19 pandemic, Millennials had a higher mortality rate than Generation X, whose rate of suicide was alarmingly high in the early 1990s. But even before that, large numbers of Millennials exhibited some of the symptoms of depression, such as difficulty thinking, sleeping, and remembering things.[2]

Journalist Anne Helen Petersen called Millennials the "Burnout Generation." In her 2020 book, OK Boomer, Let’s Talk: How My Generation Got Left Behind, journalist Jill Filipovic wrote, "...we would be rewarded and life would be, if not amazing, at least good, stable, and predictable. And well, it wasn’t."[2]

Physical health

[edit]Even though the majority of strokes affect people aged 65 or older and the probability of having a stroke doubles only every decade after the age of 55, anyone can suffer from a stroke at any age. A stroke occurs when the blood supply to the brain is disrupted, causing neurons to die within minutes, leading to irreparable brain damage, disability, or even death. Statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), strokes are the fifth leading cause of death and a major factor behind disability in the United States. According to the National Strokes Association, the risk of having a stroke is increasing among young adults (those in their 20s and 30s) and even adolescents. During the 2010s, there was a 44% increase in the number of young people hospitalized for strokes. Health experts believe this development is due to a variety of reasons related to lifestyle choices, including obesity, smoking, alcoholism, and physical inactivity. Obesity is also linked to hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. CDC data reveals that during the mid-2000s, about 28% of young Americans were obese; this number rose to 36% a decade later. Up to 80% of strokes can be prevented by making healthy lifestyle choices while the rest are due to factors beyond a person's control, namely age and genetic defects (such as congenital heart disease). In addition, between 30% and 40% of young patients suffered from cryptogenic strokes, or those with unknown causes.[175]

According to a 2019 report from the American College of Cardiology, the prevalence of heart attacks among Americans under the age of 40 increased by an average rate of two percent per year in the previous decade. About one in five patients suffered from a heart attack came from this age group. This is despite the fact that Americans in general were less likely to suffer from heart attacks than before, due in part to a decline in smoking. The consequences of having a heart attack were much worse for young patients who also had diabetes. Besides the common risk factors of heart attacks, namely diabetes, high blood pressure, and family history, young patients also reported marijuana and cocaine intake, but less alcohol consumption.[176]

Sports and fitness

[edit]Fewer American millennials follow sports than their Generation X predecessors,[177] with a McKinsey survey finding that 38 percent of millennials in contrast to 45 percent of Generation X are committed sports fans.[178] However, the trend is not uniform across all sports; the gap disappears for basketball, mixed martial arts, soccer, and collegiate sports.[177] In the United States, while the popularity of football has declined among millennials, the popularity of soccer has increased more among this group than for any other generation. As of 2018 soccer was the second most popular sport among those aged 18 to 34.[179][180] Other athletic activities popular among Millennials include boxing,[181] cycling,[182][183] running,[184] and swimming.[185] On the other hand, golf has fallen in popularity.[186][187] The Physical Activity Council's 2018 Participation Report found that millennials were more likely than other generations to participate in water sports such as stand up paddling, board-sailing and surfing. According to the survey of 30,999 Americans, which was conducted in 2017, approximately half of American millennials participated in high caloric activities while approximately one quarter were sedentary. The same report also found millennials to be more active than Baby Boomers in 2017. Thirty-five percent of both millennials and Generation X were reported to be "active to a healthy level," with millennial's activity level reported as higher overall than that of Generation X in 2017.[188][189]

Vision health

[edit]The American Optometric Association sounded the alarm on the link between the regular use of handheld electronic devices and eyestrain.[190] According to a spokeswoman, digital eyestrain, or computer vision syndrome, is "rampant, especially as we move toward smaller devices and the prominence of devices increase in our everyday lives." Symptoms include dry and irritated eyes, fatigue, eye strain, blurry vision, difficulty focusing, headaches. However, the syndrome does not cause vision loss or any other permanent damage. In order to alleviate or prevent eyestrain, the Vision Council recommends that people limit screen time, take frequent breaks, adjust screen brightness, change the background from bright colors to gray, increase text sizes, and blink more often.[191]

Dental health

[edit]Millennials struggle with dental and oral health. More than 30% of young adults have untreated tooth decay (the highest of any age group), 35% have trouble biting and chewing, and some 38% of this age group find life in general “less satisfying” due to teeth and mouth problems.[192]

Political views and participation

[edit]Views

[edit]

A 2004 Gallup poll of Americans aged 13 to 17 found that 71% said their social and political views were more or less the same as those of their parents, with just over half holding politically moderate views. (See figure above.)[193]

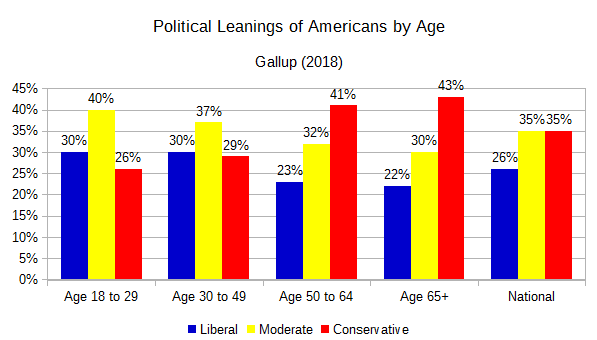

In 2018, Gallup conducted a survey of almost 14,000 Americans from all 50 states and the District of Columbia aged 18 and over on their political sympathies. They found that overall, younger adults, especially those with university degrees and women tended to lean to the left. Gallup found little variations by income groups compared to the national average.[194]

Despite their reputation for being politically liberal, Millennials do not necessarily align themselves closely with the left.[11][12] On one hand, a majority of Millennials support legalizing gay marriage[195][11] and recreational marijuana.[12] On the other hand, they disapprove of granting illegal immigrants a path towards citizenship and agree with requiring ID for voting.[11] Millennials' level of support for economic redistribution falls with higher income.[12] Millennials are almost evenly split on the issue of affirmative action.[11] On the other hand, the general comfort level of people aged 18 to 34 towards LGBT individuals has fallen noticeably by the late 2010s.[196]

Surveys conducted in 2018 by the Pew Research Center found that Millennials and Generation Z held similar views on a variety of social and political topics, setting them apart from older cohorts. Majorities of Millennials believed that climate change was real and was due to human activities, that the government should play a more active role in solving their problems, that pre-nuptial cohabitation was not wrong, and that ethnic and cultural diversity was good for society. Large numbers of Millennials thought that that single motherhood, same-sex marriage, and interracial marriage were neither a positive nor negative for society. In the case of financial responsibility in a two-parent household, though, majorities from across the generations answered that it should be shared, with 79% of both Millennials and Generation Z agreeing. Across all the generations surveyed, at least 84% thought that both parents ought to be responsible for rearing children. Very few thought that fathers should be the ones mainly responsible for taking care of children.[197]

Support for restrictions of free speech grew among Millennials on college campuses during the 2010s, reaching 40% in 2015, according to the Pew Research Center. Older generations were considerably much less supportive of this view. Pew noted similar age related trends in the United Kingdom, but not in Germany and Spain.[198] In the United States and the United Kingdom, younger Millennials frequently raised their concerns over microaggressions and advocated for safe spaces and trigger warnings in the university setting. While proponents of these restrictions have described them as conducive to inclusiveness, critics voiced their concerns regarding their impact on free speech, asserting these changes can promote censorship.[199][200] As university student Rachel Huebner wrote in The Harvard Crimson, "This undue focus on feelings has caused the college campus to often feel like a place where one has to monitor every syllable that is uttered to ensure that it could not under any circumstance offend anyone to the slightest degree."[201]

Millennials do not hold significantly different views on the topics of abortion or gun ownership than the broader American population.[13][202] In general, the older someone was, the less likely that they supported abortion. (See chart to the right.) American society at large is almost evenly split on both issues.[203][202]

In 2019, the Pew Research Center interviewed over 2,000 Americans aged 18 and over on their views of various components of the federal government. They found that 54% of the people between the ages of 18 and 29 wanted larger government and larger compared to 43% who preferred smaller government and fewer services. Meanwhile, 46% of those between the ages of 30 and 49 favored larger government compared to 49% who picked the other option. Older people were more likely to dislike larger government. Overall, the American people remain divided over the size and scope of government, with 48% preferring smaller government with fewer services and 46% larger government and more services. They found that the most popular federal agencies were the U.S. Postal Service (90% favorable), the National Park Service (86%), NASA (81%), the CDC (80%), the FBI (70%), the Census Bureau (69%), the SSA (66%), the CIA, and the Federal Reserve (both 65%). There is very little to no partisan divide on the Postal Service, the National Park Service, NASA, the CIA, the Census Bureau.[204]

In early 2019, Harvard University's Institute of Politics (IOP) Youth Poll asked voters aged 18 to 29—younger millennials and the first wave of Generation Z—what they would like to be priorities for U.S. foreign policy. They found that the top issues for these voters were countering terrorism and protecting human rights (both 39%), and protecting the environment (34%). Preventing nuclear proliferation and defending U.S. allies were not as important to young American voters.[205]

Millennials do not hold consistent views when it comes to fiscal policy.[13] Majorities support both government spending cuts and more spending on infrastructure. A slight majority also want more government services if taxes are not mentioned.[13] The Harvard IOP Youth Poll found that support for single-payer universal healthcare and free college dropped, down 8% to 47% and down 5% to 51%, respectively, if cost estimates were provided.[205] Large numbers of Millennials have a dim view of capitalism, blaming it for their problems.[2] A 2018 Gallup poll found that people aged 18 to 29 have a more favorable view of socialism than capitalism, 51% to 45%. Nationally, 56% of Americans prefer capitalism compared to 37% who favor socialism. Older Americans consistently prefer capitalism to socialism. Whether the current attitudes of millennials and Generation Z on capitalism and socialism will persist or dissipate as they grow older remains to be seen.[206] Moreover, very few Millennials can correctly define socialism.[13][12] (Also see Millennial socialism.)

According to a 2019 CBS News poll on 2,143 U.S. residents, 72% of Americans 18 to 44 years of age—Generations X, Y (Millennials), and Z—believed that it is a matter of personal responsibility to tackle climate change while 61% of older Americans did the same. In addition, 42% of American adults under 45 years old thought that the U.S. could realistically transition to 100% renewable energy by 2050, higher than for older people.[207] Even so, Millennials are less likely to consider themselves environmentalists.[13]

As is the case with many European countries, empirical evidence poses real challenges to the popular argument that the surge of nationalism and populism is an ephemeral phenomenon due to 'angry white old men' who would inevitably be replaced by younger and more liberal voters.[208] Especially since the 1970s, working-class voters, who had previously formed the backbone of support for the New Deal introduced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, have been turning away from the left-leaning Democratic Party in favor of the right-leaning Republican Party. As the Democratic Party attempted to make itself friendlier towards the university-educated and women during the 1990s, more blue-collar workers and non-degree holders left. Political scientist Larry Bartels argued because about one quarter of Democrat supporters held social views more in-tune with Republican voters and because there was no guarantee millennials would maintain their current political attitudes due to life-cycle effects, this process of political re-alignment would likely continue. As is the case with Europe, there are potential pockets of support for national populism among younger generations.[209]

Protests

[edit]A unique feature of Millennials is the role social media networks play in their social and political movements.[2] They used Facebook and Twitter to connect to like-minded individuals and issued calls to action and to coordinate their activities.[210] However, these movements were usually highly decentralized and focused on ideals rather than concrete goals or actions. As journalist Charlotte Alter explains, "There was no single objective but hundreds, or none, depending on whom you asked."[2]

The Occupy Wall Street protest of 2011 was an example of a movement dominated by Millennials.[2] When the police evicted the protestors on November 15, the movement quickly fizzled out,[211][212] ending almost two months of drama.[210] Public opinion on income inequality changed little because of these protests.[213] Richard V. Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in his book Dream Hoarders (2017) that, "...more than a third of the demonstrators on the May Day 'Occupy' march in 2011 had annual earnings of more than $100,000. But, rather than looking up in envy and resentment, the upper middle class would do well to look at their own position compared to those falling further and further behind."[214] Although later largely dismissed as a footnote in the pages of history, the Occupy Wall Street movement did have some long-term significance due to its language of resentment and (perceived) deprivation. It has led to the rise of populist politicians such as Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and Donald Trump.[210]

Votes

[edit]Millennials are more willing to vote than previous generations when they were at the same age. With voter rates being just below 50% for the four presidential cycles before 2017, they have already surpassed members of Generation X of the same age who were at just 36%.[215]

Pew Research described millennials as playing a significant role in the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States. Millennials were between 12 and 27 during the 2008 U.S. presidential election.[47] That year, the number of voters aged 18 to 29 who chose the Democratic candidate was 66%, a record since 1980. The total share of voters who backed the President's party was 53%, another record. For comparison, only 31% of voters in that age group backed John McCain, who got only 46% of the votes. Among millennials, Obama received votes from 54% of whites, 95% of blacks, and 72% of Hispanics. There was no significant difference between those with college degrees and those without, but millennial women were more likely to vote for Obama than men (69% vs. 62%). Among voters between the ages of 18 and 29, 45% identified with the Democratic Party while only 26% sided with the Republican Party, a gap of 19%. Back in 2000, the two main American political parties split the vote of this age group. This was a significant shift in the American political landscape. Millennials not only provided their votes but also the enthusiasm that marked the 2008 election. They volunteered in political campaigns and donated money.[216] But that millennial enthusiasm all but vanished by the next election cycle while older voters showed more interest.[217] In 2012, when Americans reelected Barack Obama, the voter participation gap between people above the age of 65 and those aged 18 to 24 was 31%.[209] Pew polls conducted a year prior showed that while millennials preferred Barack Obama to Mitt Romney (61% to 37%), members of the Silent Generation leaned towards Romney rather than Obama (54% to 41%). But when looking at white millennials only, Pew found that Obama's advantage which he enjoyed in 2008 ceased to be, as they were split between the two candidates.[217]

Although millennials are one of the largest voting blocs in the United States, their voting turnout rates have been subpar. Between the mid-2000s and the mid-2010s, millennial voting participation was consistently below those of their elders, fluctuating between 46% and 51%. For comparison, turnout rates for Generation X and the Baby Boomers rose during the same period, 60% to 69% and 41% to 63%, respectively, while those of the oldest of voters remained consistently at 69% or more. Millennials may still be a potent force at the ballot box, but it may be years before their participation rates reach their numerical potential as young people are consistently less likely to vote than their elders.[218] In addition, despite the hype surrounding the political engagement and possible record turnout among young voters, millennials' voting power is even weaker than first appeared due to the comparatively higher number of them who are non-citizens (12%, as of 2019), according to William Frey of the Brookings Institution.[219]

In general, the phenomenon of growing political distrust and de-alignment in the United States is similar to what has been happening in Europe since the last few decades of the twentieth century, even though events like the Watergate scandal or the threatened impeachment of President Bill Clinton are unique to the United States. Such an atmosphere depresses turnouts among younger voters. Among voters in the 18-to-24 age group, turnout dropped from 51% in 1964 to 38% in 2012. Although people between the ages of 25 and 44 were more likely to vote, their turnout rate followed a similarly declining trend during the same period. Political scientists Roger Eatwell and Matthew Goodwin argued that it was therefore unrealistic for Hillary Clinton to expect high turnout rates among millennials in 2016. This political environment also makes voters more likely to consider political outsiders such as Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump.[209] The Brookings Institution predicted that after 2016, millennials could affect how politics is conducted in the two-party system of the United States, given that they were more likely to identify as liberals or conservatives than Democrats or Republicans, respectively. In particular, while Trump supporters were markedly enthusiastic about their chosen candidate, the number of young voters identifying with the GOP has not increased.[220]

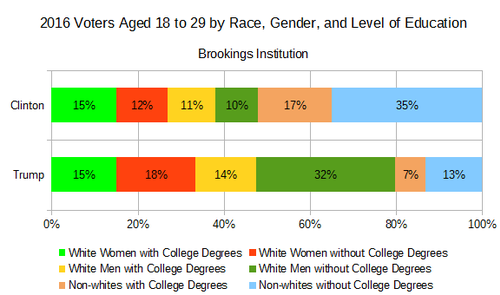

Bernie Sanders, a self-proclaimed democratic socialist and Democratic candidate in the 2016 United States presidential election, was the most popular candidate among millennial voters in the primary phase, having garnered more votes from people under 30 in 21 states than the major parties' candidates, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, did combined.[221] According to the Brookings Institution, turnout among voters aged 18 to 29 in the 2016 election was 50%. Hillary Clinton won 55% of the votes from this age group while Donald Trump secured 37%. Polls conducted right before the election showed that millennial blacks and Hispanics were concerned about a potential Trump presidency. By contrast, Trump commanded support among young whites, especially men. There was also an enthusiasm gap for the two main candidates. While 32% of young Trump supporters felt excited about the possibility of him being President, only 18% of Clinton supporters said the same about her. The Bookings Institution found that among Trump voters in the 18-to-29 age group, 15% were white women with college degrees, 18% were the same without, 14% were white men with college degrees, and 32% were the same without, for a grand total of 79%. These groups were only 48% of Clinton voters of the same age range in total. On the other hand, a total of 52% of Clinton voters aged 18 to 29 were non-whites with college degrees (17%) and non-whites without them (35%).[220] Clinton's chances of success were hampered by low turnouts among minorities and millennials with university degrees and students. Meanwhile, Trump voters included 41% of white millennials. These people tended to be non-degree holders with full-time jobs and were markedly less likely to be financially insecure than those who did not support Trump. Contrary to the claim that young Americans felt comfortable with the ongoing transformation of the ethnic composition of their country due to immigration, not all of them approve of this change despite the fact that they are an ethnically diverse cohort.[208] In the end, Trump won more votes from whites between the ages of 18 and 29 than early polls suggested.[220]

A Reuters-Ipsos survey of 16,000 registered voters aged 18 to 34 conducted in the first three months of 2018 (and before the 2018 midterm election) showed that overall support for Democratic Party among such voters fell by nine percent between 2016 and 2018 and that an increasing number favored the Republican Party's approach to the economy. Pollsters found that white millennials, especially men, were driving this change. In 2016, 47% of young whites said they would vote for the Democratic Party, compared to 33% for the Republican Party, a gap of 14% in favor of the Democrats. But in 2018, that gap vanished, and the corresponding numbers were 39% for each party. For young white men the shift was even more dramatic. In 2016, 48% said they would vote for the Democratic Party and 36% for the Republican Party. But by 2018, those numbers were 37% and 46%, respectively. This is despite the fact that almost two thirds of young voters disapproved of the performance of Republican President Donald J. Trump.[222] According to the Pew Research Center, only 27% of millennials approved of the Trump presidency while 65% disapproved that year.[223] Although American voters below the age of 30 helped Joe Biden win the 2020 U.S. Presidential election, their support for him fell quickly afterwards. By late 2021, only 29% of adults in this age group approved of his performance as President whereas 50% disapproved, a gap of 21 points, the largest of all age groups.[224] In the 2022 midterm election, voters below the age of 30 were the only major age group supporting the Democratic Party, and their numbers were large enough to prevent a 'red wave'.[225]

Preferred modes of transportation

[edit]According to the Pew Research Center, young people are more likely to ride public transit.[226] Also according to Pew, 51% of U.S. adults aged 18 to 29 used Lyft or Uber in 2018 compared to 28% in 2015. That number for all U.S. adults were 15% in 2015 and 36% in 2018. In general, users tend to be urban residents, young (18–29), university graduates, and high income earners ($75,000 a year or more).[227]

Millennials were initially not keen on getting a driver's license or owning a vehicle thanks to new licensing laws and the state of the economy when they came of age, but the oldest among them have already begun buying cars in great numbers.[228] This is consistent with what Millennials told pollsters when they were younger.[141] In 2016, millennials purchased more cars and trucks than any living generation except the Baby Boomers.[229] On the surface, the popular story is true: American millennials on average own 0.4 fewer cars than their elders. But when various factors—including income, marital status, number of children, and geographical location—were taken into account, such a distinction ceased to be.[228] In addition, once those factors are accounted for, Millennials actually drive longer distances than the Baby Boomers.[230] Economic forces, namely low gasoline prices, higher income, and suburban growth, result in Millennials having an attitude towards cars that is no different from that of their predecessors. An analysis of the National Household Travel Survey by the State Smart Transportation Initiative revealed that higher-income millennials drive less than their peers probably because they are able to afford the higher costs of living in large cities, where they can take advantage of alternative modes of transportation, including public transit and ride-hailing services.[228]

Religious beliefs

[edit]

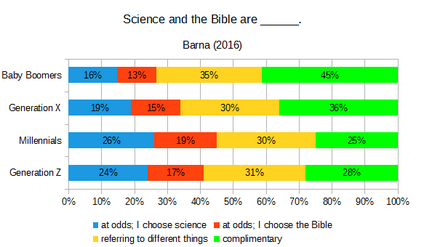

The United States has witnessed a trend towards irreligion that has been accelerating since the 1940s,[232] though the nation's rate of secularization remains slower than that in Europe.[233] American Millennials are the least likely to be religious when compared to older generations.[234] As teenagers during the 1990s and 2000s, a plurality of Millennials did not or rarely attended religious service.[2] A 2010 Pew Research Center study on millennials shows that of those between 18 and 29 years old, 25% of millennials were "Nones" and 75% were religiously affiliated.[4] On the other hand, some Millennials describe themselves as "spiritual but not religious" and will sometimes turn to astrology, meditation or mindfulness techniques possibly to seek meaning or a sense of control.[6] Overall, though, Millennials are both less religious and less spiritual.[2] Growing up in a culture that encourages individualism and free thought, Millennials tend to distrust institutions, including organized religion, and prefer a "do-it-yourself" approach to religion.[2][3][235]

A 2019 survey by Five Thirty Eight and the American Enterprise Institute identified three key reasons why Millennials were leaving religion in large numbers. Many had grown up in largely secular households and as such never felt a strong connection to organized religion. More young people had irreligious romantic partners or spouses, reinforcing their secular outlook and way of life, and those who had children were less likely to view religion as a source of morality.[5] Many Millennials are skeptical of religious doctrine, which they deem to be factually inaccurate or irrational.[3][236] Many are hostile towards religious stances, which the dismiss as judgmental, hypocritical, sexist, and homophobic.[235][236] Church scandals involving sexual molestation have further damaged the reputation of organized religion in the eyes of Millennials.[235] Unlike older cohorts, who would attempt to reconcile their personal values with religious teachings, Millennials are more likely to leave religion altogether. By the 2020s, when the oldest Millennials were in their 40s, the prediction that they could return to religion as they aged still did not come to fruition. Millennials who left religion when they were younger never returned.[2] In fact, younger Generation X and older Millennials had the greatest increase in irreligion between the 2010s and 2020s. According to political scientist Melissa Deckman, older generations were joining the young in abandoning religion as social stigma faded away.[237]

Social tendencies

[edit]Social circles

[edit]In March 2014, the Pew Research Center issued a report about how "millennials in adulthood" are "detached from institutions and networked with friends." The report said millennials are somewhat more upbeat than older adults about America's future, with 49% of millennials saying the country's best years are ahead, though they're the first in the modern era to have higher levels of student loan debt and unemployment.[238][239]

Romance and sex

[edit]Like their counterparts in some other wealthy nations, Millennials are less interested in sexual intercourse than previous generations when they were at their age, despite the fact that online dating platforms allow for the possibility of casual sex, the wide availability of contraception, and the relaxation of attitudes towards sex outside of marriage.[240] This is likely part of the ongoing trend in American society towards a slower life-history strategy, in which various adult activities are delayed. Other reasons could be the rise of the Internet, computer games, and social media. Even married couples also had sex less often. In short, people have more options.[241][242] Although this trend precedes the COVID-19 pandemic, fear of infection is likely to fuel the trend the future.[243]

Daniel Cox of Five Thirty Eight observed "a significant push back [among young Americans] against online dating as a way to meet partners." Many had been friends with their current partners before dating.[244] Meanwhile, significant number of Millennials and Generation Z is choosing to remain single, because they do not want to be in a relationship, are facing trouble meeting the right people, or have other priorities at present, such as (higher) education or careers.[245][244] Many American adults agreed that the "Me-too" movement has posed challenges for dating.[246]

Marriage and family life

[edit]

Research by the Urban Institute conducted in 2014, projected that if current trends continue, Millennials will have a lower marriage rate compared to previous generations, predicting that by age 40, 31% of millennial women will remain single, approximately twice the share of their single Gen-X counterparts. The data showed similar trends for males.[248][249] In a 2016 article, Richard Fry of the Pew Research Center described Millennials as "the group much more likely to live with their parents" who were "concentrating more on school, careers and work and less focused on forming new families, spouses or partners and children."[250][251] Compared to Baby Boomers, Millennials are less likely to get married and less likely to get divorced.[2] Indeed, fear of divorce is another reason why Millennials are not so keen on getting married.[252] Millennials who are married tend to tie the knot later in life,[253] and those who are already in a serious long-term relationship are not in a hurry to get married. As sociologist Andrew Cherlin explained, "Marriage used to be the first step into adulthood. Now it is often the last."[254] Although a majority of Millennials and Generation Z remain open to the option of marriage, significant numbers deem it to be an antiquated institution and an overwhelming majority think it is unnecessary for a fulfilling or happy life.[255] However, it was the middle class and especially the lower class that were driving the U.S. marriage rate down; marriage rates remained steady among the upper class.[256] In general, the level of education is a predictor of marriage and income. University graduates are more likely to get married but less likely to divorce.[256][257]

Married Millennial couples have shown a growing interest in sleeping in separate beds, for the sake of personal comfort, late-night work, quality sleep, and to avoid damaging their relationship. (Historically, it was not a universal norm of couples to share the same bed.)[258][141]

Research consistently shows that Millennials are much less interested in having children than older generations.[259][253] Demographers had previously expected Millennials to "catch up" as they got older and more financially secure. But the evidence did not support this. By the 2020s, the oldest Millennial women were already exiting their childbearing years without having more children.[141] Between 1990 and 2015, the number of married couples aged 18 to 34 with children dropped from 37% to 25%.[260] One reason is the rising cost of raising a child. In the United States today, it is no longer considered acceptable for a child to be unsupervised. Instead, parenting has become much more intensive and time-consuming. Extracurricular activities have become practically required and Millennial parents are spending more time with their children than previous cohorts. Even among Millennials who are gainfully employed, concerns over student loan debts loomed large.[2] Another reason is the high opportunity cost of having a child. Because Millennial women earn more money, should they choose to stay home when a baby arrives, they risk losing a significant stream of income for their households, at a time when the cost of childcare is increasing rapidly thanks to growing demands.[2] However, this has been largely a result of generational shifts in attitudes rather than economic precariousness.[261] Although concerns over climate change and financial security are commonly cited as reasons, the most popular reasons, according to various surveys, are personal independence, more leisure time, and a preference to focus on one's education and career.[2][262] In fact, about a quarter of Millennials say they do not want to have children.[263] After the Supreme Court decision Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), which returned the right to regulate aspects of abortion not covered by federal law to the individual states, the number of young and childfree adults seeking sterilization went up. Previously, it was usually middle-aged fathers who obtained vasectomies.[264][265] Tubal ligation, a sterilization procedure for women, has grown in popularity as well.[266] Meanwhile, more Millennials are choosing to have pets, referring to these animals as members of their families or their own children ("fur babies").[141] At current trend, Millennials are on track to have the lowest birth rate in history,[267][268][269] surpassing even the cohort that came of age during the First World War, the Spanish flu epidemic, and the Great Depression.[267] Even so, due to the size of Millennial cohort relative to the size of the U.S. population and because of their relatively high fertility rate, the United States will continue to maintain an economic advantage over most other developed nations, whose Millennials are not only smaller in number than their those of their elders but are also not having as high a fertility rate. The prospects of any given country is constrained by its demography.[1]

Demographer and futurist Mark McCrindle suggested the name "Generation Alpha" (or Generation ) for the offspring of a majority of Millennials,[270] people born after Generation Z,[271] noting that scientific disciplines often move to the Greek alphabet after exhausting the Roman alphabet.[271] By 2016, the cumulative number of American women of the millennial generation who had given birth at least once reached 17.3 million.[272] Compared to other cohorts, Millennials spend a lot more time at work, caring for their children, and on educational activities and less time volunteering, religious activities, and sports.[9]