English Channel

| English Channel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Western Europe; between the Celtic Sea and North Sea |

| Coordinates | 50°N 02°W / 50°N 2°W |

| Part of | Atlantic Ocean |

| Primary inflows | River Exe, River Seine, River Test, River Tamar, River Somme |

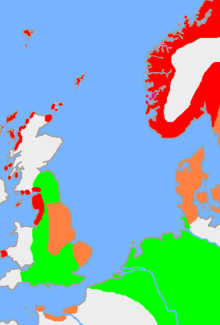

| Basin countries | United Kingdom France Bailiwick of Guernsey Bailiwick of Jersey |

| Max. depth | 174 m (571 ft) at Hurd's Deep |

| Salinity | 3.4–3.5% |

| Islands | Île de Bréhat, Île de Batz, Chausey, Tatihou, Îles Saint-Marcouf, Isle of Wight, Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, Sark, Herm |

| Settlements | Bournemouth, Brighton, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Calais, Le Havre |

The English Channel (French: la Manche, "the Sleeve" [hence German: Ärmelkanal]; Breton: Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; Cornish: Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"), also called simply the Channel, is the body of water that separates southern England from northern France, and joins the southern part of the North Sea to the rest of the Atlantic Ocean.

It is about 560 km (350 mi) long and varies in width from 240 km (150 mi) at its widest to 33.3 km (20.7 mi) in the Strait of Dover.[1] It is the smallest of the shallow seas around the continental shelf of Europe, covering an area of some 75,000 km2 (29,000 sq mi).[2]

Geography

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the English Channel as follows:[3]

- On the West. A line joining Isle Vierge (48°38′23″N 4°34′13″W / 48.63972°N 4.57028°W) to Lands End (50°04′N 5°43′W / 50.067°N 5.717°W).

- On the East. The Southwestern limit of the North Sea.

The IHO defines the southwestern limit of the North Sea as "a line joining the Walde Lighthouse (France, 1°55'E) and Leathercoat Point (England, 51°10'N)".[3] The Walde Lighthouse is 6 km east of Calais (50°59′06″N 1°55′00″E / 50.98500°N 1.91667°E), and Leathercoat Point is at the north end of St Margaret's Bay, Kent (51°10′00″N 1°24′00″E / 51.16667°N 1.40000°E).

The Strait of Dover (French: Pas de Calais), at the Channel's eastern end is its narrowest point, while its widest point lies between Lyme Bay and the Gulf of Saint Malo near its midpoint.[1] It is relatively shallow, with an average depth of about 120 m (390 ft) at its widest part, reducing to a depth of about 45 m (148 ft) between Dover and Calais. Eastwards from there the adjoining North Sea reduces to about 26 m (85 ft) in the Broad Fourteens where it lies over the watershed of the former land bridge between East Anglia and the Low Countries. It reaches a maximum depth of 180 m (590 ft) in the submerged valley of Hurd's Deep, 48 km (30 mi) west-northwest of Guernsey.[4] The eastern region along the French coast between Cherbourg and the mouth of the Seine river at Le Havre is frequently referred to as the Bay of the Seine (French: Baie de Seine).[5]

There are several major islands in the Channel, the most notable being the Isle of Wight off the English coast, and the Channel Islands, British Crown Dependencies off the coast of France. The coastline, particularly on the French shore, is deeply indented; several small islands close to the coastline, including Chausey and Mont Saint-Michel, are within French jurisdiction. The Cotentin Peninsula in France juts out into the Channel, whilst on the English side there is a small parallel channel known as the Solent between the Isle of Wight and the mainland. The Celtic Sea is to the west of the Channel.

The Channel is of geologically recent origins, having been dry land for most of the Pleistocene period. It is thought to have been created between 450,000 and 180,000 years ago by two catastrophic glacial lake outburst floods caused by the breaching of the Weald–Artois anticline, a ridge that held back a large proglacial lake in the Doggerland region, now submerged under the North Sea. The flood would have lasted for several months, releasing as much as one million cubic metres of water per second. The cause of the breach is not known but may have been an earthquake or the build-up of water pressure in the lake. The flood carved a large bedrock-floored valley down the length of the Channel, leaving behind streamlined islands and longitudinal erosional grooves characteristic of catastrophic megaflood events.[6][7] It destroyed the isthmus that connected Britain to continental Europe, although a land bridge across the southern North Sea would have existed intermittently at later times after periods of glaciation resulted in lowering of sea levels.[8]

The Channel acts as a funnel that amplifies the tidal range from less than a metre as observed at sea to more than 6 metres as observed in the Channel Islands, the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula and the north cost of Britanny. The time difference of about 6 hours between high water at the eastern and western limits of the Channel is indicative of the tidal range being amplified further by resonance.[9]

For the UK Shipping Forecast the Channel is divided into the following areas, from the west:

Name

The name English Channel has been widely used since the early 18th century, possibly originating from the designation [Engelse Kanaal] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Dutch sea maps from the 16th century onwards. In modern Dutch, however, it is known as [Het Kanaal] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (with no reference to the word "English").[10] Later, it has also been known as the British Channel[11] or the British Sea having been called the [Oceanus Britannicus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) by the 2nd-century geographer Ptolemy. The same name is used on an Italian map of about 1450, which gives the alternative name of [canalites Anglie] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)—possibly the first recorded use of the Channel designation.[12] The Anglo-Saxon texts often call it Sūð-sǣ ("South Sea") as opposed to Norð-sǣ ("North Sea" = Bristol Channel). The word channel was first recorded in Middle English in the 13th century and was borowed from Old French chanel, variant form of chenel "canal".

The French name [la Manche] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) has been in use since at least the 17th century.[2] The name is usually said to refer to the Channel's sleeve (French: la manche) shape. However, it is sometimes claimed to derive from a Celtic word meaning channel that is also the source of the name for the Minch in Scotland.[13]

In Spain and most Spanish-speaking countries the Channel is referred to as [el Canal de la Mancha] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). In Portuguese it is known as [Canal da Mancha] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). This is not a translation from French: in Portuguese and Spanish, [mancha] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) means stain, while the word for sleeve is [manga] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) – which suggests either a phonetic borrowing from French or a common source.[citation needed] There is no connection with the Spanish inland province of La Mancha. Other languages also use this name, such as Greek ([Κανάλι της Μάγχης] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), Italian ([la Manica] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Russian ([Ла-Манш] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). The German name is [Ärmelkanal] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), literally sleeve-channel, or more generally [der Kanal] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). In Danish it is kanalen (the channel or canal).

The name in Breton (Mor Breizh) means "Breton Sea", and its Cornish name (Mor Bretannek) means "British Sea".

History

Before the Devensian glaciation (the most recent ice age that ended around 10,000 years ago), Britain and Ireland were part of continental Europe, linked by an unbroken Weald-Artois Anticline, which acted as a natural dam that held back a large freshwater pro-glacial lake in the Doggerland region, now submerged under the North Sea. During this period the North Sea and almost all of the British Isles were covered with ice. The lake was fed by meltwater from the Baltic and from the Caledonian and Scandinavian ice sheets that joined to the north, blocking its exit. The sea level was about 120 m (390 ft) lower than it is today. Then, more than 200,000 years ago a single catastrophic glacial lake outburst flood overtopped the Weald-Artois Anticline and scoured a channel through an expanse of low-lying tundra, right down to the underlying chalk bedrock. In a study published in 2007[14][15] high-resolution sonar revealed the unexpectedly well-preserved scourmarks and the telltale lenticular island forms characteristic of torrential flood. Through the scoured channel passed a river which now drained the combined Rhine and Thames towards the Atlantic to the west. As the ice sheet melted, a large freshwater lake formed in the southern part of what is now the North Sea. As the meltwater could still not escape to the north (as the northern North Sea was still frozen) the outflow channel from the lake entered the Atlantic Ocean in the region of Dover and Calais.

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands.

William Shakespeare, Richard II (Act II, Scene 1)

The Channel, which delayed human reoccupation of Great Britain for more than 100,000 years,[16] has in historic times been both an easy entry for seafaring people and a key natural defence, halting invading armies while in conjunction with control of the North Sea allowing Britain to blockade the continent.[citation needed] The most significant failed invasion threats came when the Dutch and Belgian ports were held by a major continental power, e.g. from the Spanish Armada in 1588, Napoleon during the Napoleonic Wars, and Nazi Germany during World War II. Successful invasions include the Roman conquest of Britain, the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the invasion by the Dutch in 1688, while the concentration of excellent harbours in the Western Channel on Britain's south coast made possible the largest invasion of all time, the Normandy Landings in 1944. Channel naval battles include the Battle of the Downs (1639), Battle of Goodwin Sands (1652), the Battle of Portland (1653), the Battle of La Hougue (1692) and the engagement between USS Kearsarge and CSS Alabama (1864).

In more peaceful times the Channel served as a link joining shared cultures and political structures, particularly the huge Angevin Empire from 1135 to 1217. For nearly a thousand years, the Channel also provided a link between the Modern Celtic regions and languages of Cornwall and Brittany. Brittany was founded by Britons who fled Cornwall and Devon after Anglo-Saxon encroachment. In Brittany, there is a region known as "Cornouaille" (Cornwall) in French and "Kernev" in Breton[17] In ancient times there was also a "Domnonia" (Devon) in Brittany as well.

In February 1684, ice formed on the sea in a belt 3 miles (4.8 km) wide off the coast of Kent and 2 miles (3.2 km) wide on the French side.[18][19]

Route to the British Isles

Remnants of a mesolithic boatyard have been found on the Isle of Wight. Wheat was traded across the Channel about 8,000 years ago.[20][21] "... Sophisticated social networks linked the Neolithic front in southern Europe to the Mesolithic peoples of northern Europe." The Ferriby Boats, Hanson Log Boats and the later Dover Bronze Age Boat could carry a substantial cross-Channel cargo.[22]

Diodorus Siculus and Pliny[23] both suggest trade between the rebel Celtic tribes of Armorica and Iron Age Britain flourished. In 55 BC Julius Caesar invaded, claiming that the Britons had aided the Veneti against him the previous year. He was more successful in 54 BC, but Britain was not fully established as part of the Roman Empire until completion of the invasion by Aulus Plautius in 43 AD. A brisk and regular trade began between ports in Roman Gaul and those in Britain. This traffic continued until the end of Roman rule in Britain in 410 AD, after which the early Anglo-Saxons left less clear historical records.

In the power vacuum left by the retreating Romans, the Germanic Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began the next great migration across the North Sea. Having already been used as mercenaries in Britain by the Romans, many people from these tribes crossed during the Migration Period, conquering and perhaps displacing the native Celtic populations.[24]

Norsemen and Normans

The attack on Lindisfarne in 793 is generally considered the beginning of the Viking Age. For the next 250 years the Scandinavian raiders of Norway, Sweden, and Denmark dominated the North Sea, raiding monasteries, homes, and towns along the coast and along the rivers that ran inland. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle they began to settle in Britain in 851. They continued to settle in the British Isles and the continent until around 1050.[25]

The fiefdom of Normandy was created for the Viking leader Rollo (also known as Robert of Normandy). Rollo had besieged Paris but in 911 entered vassalage to the king of the West Franks Charles the Simple through the Treaty of St.-Claire-sur-Epte. In exchange for his homage and fealty, Rollo legally gained the territory he and his Viking allies had previously conquered. The name "Normandy" reflects Rollo's Viking (i.e. "Northman") origins.

The descendants of Rollo and his followers adopted the local Gallo-Romance language and intermarried with the area's inhabitants and became the Normans – a Norman French-speaking mixture of Scandinavians, Hiberno-Norse, Orcadians, Anglo-Danish, and indigenous Franks and Gauls.

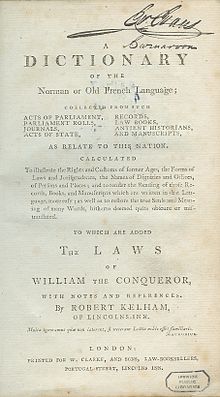

Rollo's descendant William, Duke of Normandy became king of England in 1066 in the Norman Conquest beginning with the Battle of Hastings, while retaining the fiefdom of Normandy for himself and his descendants. In 1204, during the reign of King John, mainland Normandy was taken from England by France under Philip II, while insular Normandy (the Channel Islands) remained under English control. In 1259, Henry III of England recognised the legality of French possession of mainland Normandy under the Treaty of Paris. His successors, however, often fought to regain control of mainland Normandy.

With the rise of William the Conqueror the North Sea and Channel began to lose some of their importance. The new order oriented most of England and Scandinavia's trade south, toward the Mediterranean and the Orient.

Although the British surrendered claims to mainland Normandy and other French possessions in 1801, the monarch of the United Kingdom retains the title Duke of Normandy in respect to the Channel Islands. The Channel Islands (except for Chausey) are Crown dependencies of the British Crown. Thus the Loyal toast in the Channel Islands is La Reine, notre Duc ("The Queen, our Duke"). The British monarch is understood to not be the Duke of Normandy in regards of the French region of Normandy described herein, by virtue of the Treaty of Paris of 1259, the surrender of French possessions in 1801, and the belief that the rights of succession to that title are subject to Salic Law which excludes inheritance through female heirs.

French Normandy was occupied by English forces during the Hundred Years' War in 1346–1360 and again in 1415–1450.

England and Britain: Naval superpower

From the reign of Elizabeth I, English foreign policy concentrated on preventing invasion across the Channel by ensuring no major European power controlled the potential Dutch and Flemish invasion ports. Her climb to the pre-eminent sea power of the world began in 1588 as the attempted invasion of the Spanish Armada was defeated by the combination of outstanding naval tactics by the English and the Dutch under command of Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham with Sir Francis Drake second in command, and the following stormy weather. Over the centuries the Royal Navy slowly grew to be the most powerful in the world.[26]

The building of the British Empire was possible only because the Royal Navy eventually managed to exercise unquestioned control over the seas around Europe, especially the Channel and the North Sea. During the Seven Years' War, France attempted to launch an invasion of Britain. To achieve this France needed to gain control of the Channel for several weeks, but was thwarted following the British naval victory at the Battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759.

Another significant challenge to British domination of the seas came during the Napoleonic Wars. The Battle of Trafalgar took place off the coast of Spain against a combined French and Spanish fleet and was won by Admiral Horatio Nelson, ending Napoleon's plans for a cross-Channel invasion and securing British dominance of the seas for over a century.

First World War

The exceptional strategic importance of the Channel as a tool for blockade was recognised by the First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher in the years before World War I. "Five keys lock up the world! Singapore, the Cape, Alexandria, Gibraltar, Dover."[27] However, on 25 July 1909 Louis Blériot made the first Channel crossing from Calais to Dover in an aeroplane. Blériot's crossing signalled the end of the Channel as a barrier-moat for England against foreign enemies.

Because the Kaiserliche Marine surface fleet could not match the British Grand Fleet, the Germans developed submarine warfare, which was to become a far greater threat to Britain. The Dover Patrol was set up just before the war started to escort cross-Channel troopships and to prevent submarines from sailing in the Channel, obliging them to travel to the Atlantic via the much longer route around Scotland.

On land, the German army attempted to capture Channel ports in the Race to the Sea but although the trenches are often said to have stretched "from the frontier of Switzerland to the English Channel", they reached the coast at the North Sea. Much of the British war effort in Flanders was a bloody but successful strategy to prevent the Germans reaching the Channel coast.

At the outset of the war, an attempt was made to block the path of U-boats through the Dover Strait with naval minefields. By February 1915, this had been augmented by a 25 kilometres (16 mi) stretch of light steel netting called the Dover Barrage, which it was hoped would ensnare submerged submarines. After initial success, the Germans learned how to pass through the barrage, aided by the unreliability of British mines.[28] On 31 January 1917, the Germans restarted unrestricted submarine warfare leading to dire Admiralty predictions that submarines would defeat Britain by November,[29] the most dangerous situation Britain faced in either world war.

The Battle of Passchendaele in 1917 was fought to reduce the threat by capturing the submarine bases on the Belgian coast, though it was the introduction of convoys and not capture of the bases that averted defeat. In April 1918 the Dover Patrol carried out the famous Zeebrugge Raid against the U-boat bases. During 1917, the Dover Barrage was re-sited with improved mines and more effective nets, aided by regular patrols by small warships equipped with powerful searchlights. A German attack on these vessels resulted in the Battle of Dover Strait in 1917.[30] A much more ambitious attempt to improve the barrage, by installing eight massive concrete towers across the strait was called the Admiralty M-N Scheme but only two towers were nearing completion at the end of the war and the project was abandoned.[31]

The naval blockade in the Channel and North Sea was one of the decisive factors in the German defeat in 1918.[32]

Second World War

During the Second World War, naval activity in the European theatre was primarily limited to the Atlantic. During the Battle of France in May 1940, the Germans succeeded in capturing both Boulogne and Calais, thereby threatening the line of retreat for the British Expeditionary Force. By a combination of hard fighting and German indecision, the port of Dunkirk was kept open allowing 338,000 Allied troops to be evacuated in Operation Dynamo. More than 11,000 were evacuated from Le Havre during Operation Cycle[33] and a further 192,000 were evacuated from ports further down the coast in Operation Ariel in June 1940.[34] The early stages of the Battle of Britain[35] featured air attacks on Channel shipping and ports, and until the Normandy Landings (with the exception of the Channel Dash) the narrow waters were too dangerous for major warships. Despite these early successes against shipping, the Germans did not win the air supremacy necessary for Operation Sealion, the projected cross-Channel invasion.

The Channel subsequently became the stage for an intensive coastal war, featuring submarines, minesweepers, and Fast Attack Craft.[36]

Dieppe was the site of an ill-fated raid by Canadian and British armed forces. More successful was the later Operation Overlord (D-Day), a massive invasion of German-occupied France by Allied troops. Caen, Cherbourg, Carentan, Falaise and other Norman towns endured many casualties in the fight for the province, which continued until the closing of the so-called Falaise gap between Chambois and Montormel, then liberation of Le Havre.

The Channel Islands were the only part of the British Commonwealth occupied by Germany (excepting the part of Egypt occupied by the Afrika Korps at the time of the Second Battle of El Alamein, which was a protectorate and not part of the Commonwealth). The German occupation of 1940–1945 was harsh, with some island residents being taken for slave labour on the Continent; native Jews sent to concentration camps; partisan resistance and retribution; accusations of collaboration; and slave labour (primarily Russians and eastern Europeans) being brought to the islands to build fortifications.[citation needed] The Royal Navy blockaded the islands from time to time, particularly following the liberation of mainland Normandy in 1944. Intense negotiations resulted in some Red Cross humanitarian aid, but there was considerable hunger and privation during the occupation, particularly in the final months, when the population was close to starvation. The German troops on the islands surrendered on 9 May 1945, a few days after the final surrender in mainland Europe.

Population

The English Channel is far more densely populated on the English shore. The most significant towns and cities along both the English and French sides of the Channel (each with more than 20,000 inhabitants, ranked in descending order; populations are the urban area populations from the 1999 French census, 2001 UK census, and 2001 Jersey census) are as follows:

England

- Brighton–Worthing–Littlehampton: 461,181 inhabitants, made up of:

- Portsmouth: 442,252, including

- Gosport: 79,200

- Bournemouth & Poole: 383,713

- Southampton: 304,400

- Plymouth: 258,700

- Torbay (Torquay): 129,702

- Hastings–Bexhill: 126,386

- Exeter: 119,600

- Eastbourne: 106,562

- Bognor Regis: 62,141

- Folkestone–Hythe: 60,039

- Weymouth: 56,043

- Dover: 39,078

- Walmer–Deal: 35,941

- Exmouth: 32,972

- Falmouth–Penryn: 28,801

- Ryde: 22,806

- St Austell: 22,658

- Seaford: 21,851

- Falmouth: 21,635

- Penzance: 20,255

France

- Le Havre: 248,547 inhabitants

- Calais: 104,852

- Boulogne-sur-Mer: 92,704

- Cherbourg: 42,318

- Saint-Brieuc: 45,879

- Saint-Malo: 50,675

- Lannion–Perros-Guirec: 48,990

- Dieppe: 42,202

- Morlaix: 35,996

- Dinard: 25,006

- Étaples–Le Touquet-Paris-Plage: 23,994

- Fécamp: 22,717

- Eu–Le Tréport: 22,019

- Trouville-sur-Mer–Deauville: 20,406

Channel Islands

- Saint Helier, Jersey: 28,310 inhabitants

- Saint Peter Port, Guernsey: 16,488 inhabitants

- Saint Anne, Alderney: 2,200 inhabitants

- Sark: 600 inhabitants

- Herm: 60 inhabitants

Shipping

The Channel has traffic on both the UK-Europe and North Sea-Atlantic routes, and is the world's busiest seaway, with over 500 ships per day.[37] Following an accident in January 1971 and a series of disastrous collisions with wreckage in February,[38] the Dover TSS[39] the world's first radar-controlled Traffic Separation Scheme was set up by the International Maritime Organization. The scheme mandates that vessels travelling north must use the French side, travelling south the English side. There is a separation zone between the two lanes.[40]

In December 2002 the MV Tricolor, carrying £30m of luxury cars sank 32 km (20 mi) northwest of Dunkirk after collision in fog with the container ship Kariba. The cargo ship Nicola ran into the wreckage the next day. There was no loss of life.[citation needed]

The shore-based long range traffic control system was updated in 2003 and there is a series of Traffic Separation Systems in operation.[41] Though the system is inherently incapable of reaching the levels of safety obtained from aviation systems such as the Traffic Collision Avoidance System, it has reduced accidents to one or two per year.[citation needed]

Marine GPS systems allow ships to be preprogrammed to follow navigational channels accurately and automatically, further avoiding risk of running aground, but following the fatal collision between Dutch Aquamarine and Ash in October 2001, Britain's Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) issued a safety bulletin saying it believed that in these most unusual circumstances GPS use had actually contributed to the collision.[42] The ships were maintaining a very precise automated course, one directly behind the other, rather than making use of the full width of the traffic lanes as a human navigator would.

A combination of radar difficulties in monitoring areas near cliffs, a failure of a CCTV system, incorrect operation of the anchor, the inability of the crew to follow standard procedures of using a GPS to provide early warning of the ship dragging the anchor and reluctance to admit the mistake and start the engine led to the MV Willy running aground in Cawsand bay, Cornwall in January 2002. The MAIB report makes it clear that the harbour controllers were informed of impending disaster by shore observers before the crew were themselves aware.[43] The village of Kingsand was evacuated for three days because of the risk of explosion, and the ship was stranded for 11 days.[44][45][46]

Ecology

As a busy shipping lane, the Channel experiences environmental problems following accidents involving ships with toxic cargo and oil spills.[47] Indeed, over 40% of the UK incidents threatening pollution occur in or very near the Channel.[48] One of the recent occurrences was the MSC Napoli, which on 18 January 2007 was beached with nearly 1700 tonnes of dangerous cargo in Lyme Bay, a protected World Heritage Site coastline.[citation needed] The ship had been damaged and was en route to Portland Harbour.

Transport

Ferry

The number of ferry routes crossing the Strait of Dover has reduced since the Channel Tunnel opened. Current cross-channel ferry routes are:

- Dover-Calais

- Dover-Dunkirk

- Newhaven-Dieppe

- Portsmouth-Ouistreham

- Portsmouth-Cherbourg

- Portsmouth-Le Havre

- Portsmouth-Saint Malo

- Portsmouth-Jersey & Guernsey

- Poole-Saint Malo

- Poole-Cherbourg

- Weymouth-Saint Malo

- Plymouth-Roscoff

Channel Tunnel

Many travellers cross beneath the Channel using the Channel Tunnel, first proposed in the early 19th century and finally opened in 1994, connecting the UK and France by rail. It is now routine to travel between Paris or Brussels and London on the Eurostar train. Cars can also be carried on special trains between Folkestone and Calais.

Economy

Tourism

The coastal resorts of the Channel, such as Brighton and Deauville, inaugurated an era of aristocratic tourism in the early 19th century, which developed into the seaside tourism that has shaped resorts around the world.[citation needed] Short trips across the Channel for leisure purposes are often referred to as Channel Hopping.

Culture and languages

The two dominant cultures are English on the north shore of the Channel, French on the south. However, there are also a number of minority languages that are or were found on the shores and islands of the English Channel, which are listed here, with the Channel's name following them.

- Celtic Languages

- Breton – "Mor Breizh" (Sea of Brittany)

- Cornish – "Mor Bretannek"

- Template:Lang-ga – "Merciful Sea"

- Germanic languages

- English

- Dutch – "het Kanaal" (the Channel)

Dutch previously had a larger range, and extended into parts of modern-day France. For more information, please see French Flemish.

- Romance languages

- French – "La Manche"

- Gallo – "Manche", "Grand-Mè", "Mè Bertone"[49]

- Norman, including the Channel Island vernaculars:

- Anglo-Norman (extinct, but fossilised in certain English law phrases)

- Auregnais (extinct)

- Cotentinais – "Maunche"

- Guernesiais – "Ch'nal"

- Jèrriais – "Ch'na"

- Sercquais

- Picard

Most other languages tend towards variants of the French and English forms, but notably Welsh has "Môr Udd".

Channel crossings

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2013) |

As one of the narrowest and most well-known international waterways lacking dangerous currents, the Channel has been the first objective of numerous innovative sea, air, and human powered crossing technologies.[citation needed] Pre-historic people sailed from the mainland to England for millennia. At the end of the last Ice Age, lower sea levels even permitted walking across.[50][51]

By boat

| Date | Crossing | Participant(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| March 1816 | the French paddle steamer Élise (ex Scottish-built Margery or Margory) was the first steamer to cross the Channel. | ||

| 9 May 1816 | Paddle steamer Defiance, Captain William Wager, was the first steamer to cross the Channel to Holland[52] | ||

| 10 June 1821 | Paddle steamer Rob Roy, first passenger ferry to cross channel | The steamer was purchased subsequently by the French postal administration and renamed Henri IV. | |

| June 1843 | First ferry connection through Folkestone-Boulogne | Commanding officer Captain Hayward | |

| 25 July 1959 | Hovercraft crossing (Calais to Dover, 2 hours 3 minutes) | SR-N1 | Sir Christopher Cockerell was on board |

| 22 August 1972 | First solo hovercraft crossing (same route as SR-N1; 2 hours 20 minutes)[53] | Nigel Beale (UK) | |

| 1974 | Coracle (13 and a half hours) | Bernard Thomas (UK) | As part of a publicity stunt, the journey was undertaken to demonstrate how the Bull Boats of the Mandan Indians of North Dakota could have been copied from Welsh coracles introduced by Prince Madog in the 12th century.[54] |

| 14 September 1995 | Fastest crossing by hovercraft, 22 minutes by "Princess Anne" | MCH SR-N4 MkIII | Craft was designed as a ferry |

| 1997 | First vessel to complete a solar-powered crossing using photovoltaic cells | SB Collinda | — |

| 14 June 2004 | New record time for crossing in amphibious vehicle (the Gibbs Aquada, three-seater open-top sports car) | Richard Branson (UK) | Completed crossing in 1 hour 40 minutes 6 seconds – previous record was 6 hours.[citation needed] |

| 26 July 2006 | New record time for crossing in hydrofoil car (the Rinspeed Splash, two-seater open-top sports car) | Frank M. Rinderknecht (Switzerland) | Completed crossing in 3 hours 14 minutes[55] |

| 25 September 2006 | First crossing on a towed inflatable object (not a powered inflatable boat) | Stephen Preston (UK) | Completed crossing in 180 min[56] |

| July 2007 | BBC Top Gear presenters "drive" to France in amphibious cars | Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond, James May (UK) | Completed the crossing in a 1996 Nissan D21 pick-up (the "Nissank"), fitted with a Honda outboard engine.[57] |

| 1960's | First crossing by water ski. | An annual Cross Channel Ski Race was run from the Varne Boat Club from the 1960s onwards. The race was from the Varne club in Greatstone on Sea to Cap Gris Nez / Boulogne (latter years) and back. Many waterskiers have made this return crossing non stop since this time.[citation needed] Youngest known waterskier to cross the Channel was John Clements aged 10, from the Varne Boat Club on 22 August 1974 who made the crossing from Littlestone to Boulogne and back without falling.[citation needed] | |

| 20 August 2011 | First Crossing by Sea Scooters | A four-man relay team from Scarborough, North Yorkshire, headed by Heath Samples, crossed from Shakespeare Beach to Wissant.[citation needed] | It took 12 hours 26 minutes 39 seconds and set a new Guinness World Record. |

Pierre Andriel crossed the English Channel aboard the Élise, ex the Scottish p.s. "Margery" in March 1816, one of the earliest seagoing voyages by steam ship.

The paddle steamer Defiance, Captain William Wager, was the first steamer to cross the Channel to Holland, arriving there on 9 May 1816.[52]

On 10 June 1821, English-built paddle steamer Rob Roy was the first passenger ferry to cross channel. The steamer was purchased subsequently by the French postal administration and renamed Henri IV and put into regular passenger service a year later. It was able to make the journey across the Straits of Dover in around three hours.[58]

In June 1843, because of difficulties with Dover harbour, the South Eastern Railway company developed the Boulogne-sur-Mer-Folkestone route as an alternative to Calais-Dover. The first ferry crossed under the command of Captain Hayward.[59]

In 1974 a Welsh coracle piloted by Bernard Thomas of Llechryd crossed the English Channel to France in 13½ hours. The journey was undertaken to demonstrate how the Bull Boats of the Mandan Indians of North Dakota could have been copied from coracles introduced by Prince Madog in the 12th century.[60][61]

The Mountbatten class hovercraft (MCH) entered commercial service in August 1968, initially between Dover and Boulogne but later also Ramsgate (Pegwell Bay) to Calais. The journey time Dover to Boulogne was roughly 35 minutes, with six trips per day at peak times. The fastest crossing of the English Channel by a commercial car-carrying hovercraft was 22 minutes, recorded by the Princess Anne MCH SR-N4 Mk3 on 14 September 1995,[62]

By air

The first aircraft to cross the Channel was a balloon in 1785, piloted by Jean Pierre François Blanchard (France) and John Jeffries (US).[63]

Louis Blériot (France) piloted the first airplane to cross in 1909.

By swimming

The sport of Channel swimming traces its origins to the latter part of the 19th century when Captain Matthew Webb made the first observed and unassisted swim across the Strait of Dover, swimming from England to France on 24–25 August 1875 in 21 hours 45 minutes.

In 1927, at a time when fewer than ten swimmers (including the first woman, Gertrude Ederle in 1926) had managed to emulate the feat and many dubious claims were being made, the Channel Swimming Association (CSA) was founded to authenticate and ratify swimmers' claims to have swum the Channel and to verify crossing times. The CSA was dissolved in 1999 and was succeeded by two separate organisations: CSA (Ltd) and the Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation (CSPF). Both observe and authenticate cross-Channel swims in the Strait of Dover. The Channel Crossing Association was set up at about this time to cater for unorthodox crossings.

The team with the most number of Channel swims to its credit is the Serpentine Swimming Club in London,[64] followed by the International Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team.[65]

By the end of 2005, 811 people had completed 1,185 verified crossings under the rules of the CSA, the CSA (Ltd), the CSPF and Butlins.

The number of swims conducted under and ratified by the Channel Swimming Association to 2005 was 982 by 665 people. This includes 24 two-way crossings and three three-way crossings.

The number of ratified swims to 2004 was 948 by 675 people (456 men, 214 women). There have been 16 two-way crossings (9 by men and 7 by women). There have been three three-way crossings (2 by men and 1 by a woman). (It is unclear whether this last set of data is comprehensive or CSA only.)

The Strait of Dover is the busiest stretch of water in the world. It is governed by International Law as described in Unorthodox Crossing of the Dover Strait Traffic Separation Scheme.[66] It states: "[In] exceptional cases the French Maritime Authorities may grant authority for unorthodox craft to cross French territorial waters within the Traffic Separation Scheme when these craft set off from the British coast, on condition that the request for authorisation is sent to them with the opinion of the British Maritime Authorities."

The CCA, CSA, and CS&PF are the organisations escorting channel swims, because their pilots have the experience, qualifications, and equipment to guarantee the safety of the swimmers they escort.

The fastest verified swim of the Channel was by the Australian Trent Grimsey on 8 September 2012, in 6 hours 55 minutes,[67][68] beating the previous record set in 2007 by Bulgarian swimmer Petar Stoychev.

There may have been some unreported swims of the Channel, by people intent on entering Britain in circumvention of immigration controls. A failed attempt to cross the Channel by two Syrian refugees in October 2014 only came to light when their bodies were later discovered on the shores of the North Sea in Norway and the Netherlands.[69]

By car

On 16 September 1965, two Amphicars crossed from Dover to Calais. One was crewed by two British Army officers, Captain Mike Bailey REME and Captain Peter Tappenden RAOC, the other by Tim Dill-Russell and Sgt Joe Minto RASC. The crossing took 7 hours 20 minutes, with mid-Channel wind conditions reaching force 5 on the Beaufort scale. The cars went on to the Frankfurt Motor Show that year, where they were put on display.[70]

In 2007, the presenters of the BBC programme Top Gear (Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond and James May) "drove" across the Channel from England to France. They did it by designing "amphibious cars" that could be driven on land and also operate in water. After four attempts – twice failing to leave Dover Harbour – they reached the coast of France in a Nissan pick-up with an outboard motor and oil drums attached to the back to aid stability in open water.[57] The other two vehicles that attempted the crossing (a Triumph Herald with a sail and a Volkswagen Campervan with a propeller attached to the flywheel) both sank.[71] Clarkson believed it might be possible to break the world record for crossing the Channel in this manner, but the team was unsuccessful.[72] The Daily Mail claimed that the BBC received criticism from a coastguard who claimed that they had not been told that the stunt was going to take place, and allegedly branded it "completely irresponsible"; however this was not reported by any other media sources and the aired episode showed the full co-operation of the coastguard.[73]

Other types

| Date | Crossing | Participant(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 27 March 1899 | First radio transmission across the Channel (from Wimereux to South Foreland Lighthouse) | Guglielmo Marconi (Italy) |

See also

References

- ^ a b "English Channel". The Columbia Encyclopedia, 2004.

- ^ a b "English Channel." Encyclopædia Britannica 2007.

- ^ a b "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition + corrections" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1971. pp. 42 [corrections to page 13] and 6. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- ^ "English Channel." The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia including Atlas. 2005.

- ^ File:Allied Invasion Force.jpg + French map of Channel

- ^ Gupta, Sanjeev; Jenny S. Collier, Andy Palmer-Felgate & Graeme Potter; Palmer-Felgate, Andy; Potter, Graeme (2007). "Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel". Nature. 448 (7151): 342–345. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..342G. doi:10.1038/nature06018. PMID 17637667. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - ^ "GPG Cambridge.ac Physics Today, Sonar mapping suggests that the English Channel was created by two megafloods, (extract of Gupta Potter), Freely downloadabe PDF" (PDF). Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Professor Bryony Coles. "The Doggerland project". University of Exeter. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Thompson, LuAnne. "Tide Dynamics – Dynamic Theory of Tides" (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ^ "Buitenlandse Aardrijkskundige Namen" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Taalunie. 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "A chart of the British Channel, Jefferys, Thomas, 1787". Davidrumsey.com. 22 February 1999. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ "Map Of Great Britain, Ca. 1450". The unveiling of Britain. British Library. 26 March 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

This may also be the first map to name the English Channel: "britanicus oceanus nunc canalites Anglie"

- ^ Room A. Placenames of the world: origins and meanings, p. 6.

- ^ Sanjeev Gupta et al. "Catastrophic flooding origin of shelf valley systems in the English Channel" Nature448, 342–345 (19 July 2007) (abstract)

- ^ "Catastrophic Flooding Changed The Course Of British History", Science Daily (19 July 2007).

- ^ " Researchers speculate that the flooding induced changes in topography creating barriers to migration which led to a complete absence of humans in Britain 100,000 years ago." (ScienceDaily (19 July 2007).

- ^ cf. "Kernow", the Cornish for Cornwall.

- ^ Hermann Flohn, Roberto Fantechi, The Climate of Europe, past, present, and future, 1984, ISBN 90-277-1745-1, p.46

- ^ PastPresented,info: The Great Frost of 1683–4

- ^ Balter, Michael (26 February 2015). "DNA recovered from underwater British site may rewrite history of farming in Europe". Science.

- ^ Larson, Greger (26 February 2015). "How wheat came to Britain". Science. 347: 945–946. doi:10.1126/science.aaa6113.

- ^ Smith, Oliver; Momber, Garry; Bates, Richard; Garwood, Paul (27 February 2015). "Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago". Science. 347 (6225): 998–1001. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..998S. doi:10.1126/science.1261278. PMID 25722413.

- ^ "History Compass" (PDF). History Compass. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Germany The migration period". Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Nick Attwood MA. "The Holy Island of Lindisfarne – The Viking Attack". Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ britishbattles.com (2007). "The Spanish Armada: Sir Francis Drake". Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ Geoffrey Miller. The Millstone: Chapter 2. Retrieved 1 November 2008. quoting Fisher, Naval Necessities I, p. 219

- ^ firstworldwar.com – Encyclopedia – The Dover Barrage

- ^ "U-Boat warfare at the Atlantic during World War I". German Notes. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Robert M. Grant, U-Boats Destroyed: The Effect of Anti-Submarine Warfare 1914–1918, Periscope Publishing Ltd 2002, ISBN 1-904381-00-6 (pp. 74–75)

- ^ Black Jack (Quarterly Magazine Southampton Branch World Ship Society) Issue No: 152 Autumn 2009: (p.6) SHOREHAM TOWERS – One of the Admiralty’s greatest engineering secrets, Reproduced from Engineering & Technology IET Magazine May 2009

- ^ "His Imperial German Majesty's U-boats in WWI: 6. Finale". uboat.net. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "Operation Cycle, the evacuation from Havre, 10-13 June 1940". Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ^ Operation Aerial, the evacuation from north western France, 15–25 June 1940. Historyofwar.org. Retrieved on 29 July 2013.

- ^ "Fact File: Battle of Britain". BBC. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Campaigns of World War II, Naval History Homepage. "Atlantic, WW2, U-boats, convoys, OA, OB, SL, HX, HG, Halifax, RCN ..." Retrieved 24 July 2007.

- ^ "The Dover Strait, navigation rules". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2007. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ "History of CNIS". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Dover Strait TSS". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "World Marine Guide – English Channel". Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ Chartlets published by the Maritime and Coastguard Agency

- ^ "Safety Bulletin 2" (PDF). Marine Accident Investigation Branch. 2001. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Report on the Investigation of the grounding of MV Willy" (PDF). Marine Accident Investigation Branch. October 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Picture gallery: Cornwall's stranded tanker". London: BBC. 5 January 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Salvage team hunts for leak". London: BBC. 6 January 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Stranded tanker safe in port". London: BBC. 14 January 2002. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Tanker wreck starts leaking oil". London: BBC. 1 February 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Annual Survey of Reported Discharges" (PDF). Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Auffray, Régis (2007). Le Petit Matao. Rue des Scribes. ISBN 2906064645.

- ^ "The Doggerland Project", University of Exeter Department of Archaeology

- ^ Patterson, W, "Coastal Catastrophe" (paleoclimate research document), University of Saskatchewan

- ^ a b Dawson, Charles (February 1998). "P. S. Defiance, the first steamer to Holland, 9 May 1816". The Mariner's Mirror. 84 (1). The Society for Nautical Research: 84.

- ^ Verifiable in Hovercraft Club of Great Britain Records and Archives

- ^ "Wales on Britannia: Facts About Wales & the Welsh". Britannia.com. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ Stuart Waterman (27 July 2006). "Rinspeed "Splash" sets English Channel record". Autoblog. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Inflatable Drag". Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ a b "1996 Nissan Truck [D21] in "Top Gear, 2002–2010"". IMCDb.org. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- ^ The History of the Channel Ferry

- ^ [1] Channel ferries & ferry ports

- ^ Wales on Britannia: Facts About Wales & the Welsh

- ^ John, Gilbert (5 April 2008). "'Coracle king' to hang up paddle". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "Hovercraft deal opens show". London: BBC News. 15 June 1966. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Blanchard, Jean-Pierre-François." Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- ^ serpentineswimmingclub.com "Serpentine Swimming Club". Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ srichinmoyraces.org "Sri Chinmoy Marathon Team". Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- ^ "Unorthodox Crossing of the Dover Strait Traffic Separation Scheme". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Trent Grimsey breaks channel swim record, The Age, 13 September 2012

- ^ Channel swimming records

- ^ Fjellberg, Anders (2015), The Wetsuitmen

- ^ Autocar article entitled Cars Ahoy published 10 December 1965

- ^ Series Ten, Episode Two

- ^ BBC Top Gear Series 10 Episode 2

- ^ "Coastguards' fury as Top Gear stars attempt to 'drive' across the Channel | Mail Online". Daily Mail. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

External links

- Full Channel swim lists and swimmer information

- Oceanus Britannicus or British Sea

- Channel swimmers website

- Archives of long distance swimming

- Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation

- Channel Swimming Association

- World War II Eye Witness Account – Audio Recording Air Battle over the English Channel (1940)