Carbon emission trading

Carbon emission trading (also called carbon market, emission trading scheme (ETS) or cap and trade) is a type of emissions trading scheme designed for carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs). A form of carbon pricing, its purpose is to limit climate change by creating a market with limited allowances for emissions. Carbon emissions trading is a common method that countries use to attempt to meet their pledges under the Paris Agreement, with schemes operational in China, the European Union, and other countries.[1]

Emissions trading sets a quantitative total limit on the emissions produced by all participating emitters, which correspondingly determines the prices of emissions. Under emission trading, a polluter having more emissions than their quota has to purchase the right to emit more from emitters with fewer emissions. This can reduce the competitiveness of fossil fuels, which are the main driver of climate change. Instead, carbon emissions trading may accelerate investments into renewable energy, such as wind power and solar power.[2]: 12

However, such schemes are usually not harmonized with defined carbon budgets that are required to maintain global warming below the critical thresholds of 1.5 °C or "well below" 2 °C, with oversupply leading to low prices of allowances with almost no effect on fossil fuel combustion.[3] Emission trade allowances currently cover a wide price range from €7 per tonne of CO2 in China's national carbon trading scheme[4] to €63 per tonne of CO2 in the EU-ETS (as of September 2021).[5]

Other greenhouse gases can also be traded but are quoted as standard multiples of carbon dioxide with respect to their global warming potential.

Purpose

[edit]The economic problem with climate change is that the emitters of greenhouse gases (GHGs) do not face the external costs of their actions, which include the present and future welfare of people, the natural environment,[6][7][8] and the social cost of carbon. This can be addressed with the dynamic price model of emissions trading.

An emissions trading scheme for greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) works by establishing property rights for the atmosphere.[9] The atmosphere is a global public good, and GHG emissions are an international externality. In the cap-and-trade variant of emissions trading, a cap on access to a resource is defined and then allocated among users in the form of permits. Compliance is established by comparing actual emissions with permits surrendered.[10] The setting of the cap affects the environmental integrity of carbon trading, and can result in both positive and negative environmental effects.[11]

Emissions trading programmes such as the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) complement the country-to-country trading stipulated in the Kyoto Protocol by allowing private trading of permits, coordinating with national emissions targets provided under the Kyoto Protocol. Under such programmes, a national or international authority allocates permits to individual companies based on established criteria, with a view to meeting targets at the lowest overall economic cost.[12]

History

[edit]"Economy-wide pricing of carbon is the centre piece of any policy designed to reduce emissions at the lowest possible costs".

Ross Garnaut, lead author of the Garnaut Climate Change Review in 2011[13]

Carbon emission trading began in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, when 160 countries agreed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The necessary detail was left to be settled by the UN Conference of Parties (COP).

In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol was the first major agreement to reduce greenhouse gases. 38 developed countries committed themselves to targets and timetables.[14] The resulting inflexible limitations on GHG growth could entail substantial costs if countries have to solely rely on their own domestic measures.[15]

Carbon emissions trading increased rapidly in 2021 with the start of the Chinese national carbon trading scheme.[16] The increasing costs of permits on the EU ETS have had the effect of increasing costs of coal power.[17]

A 2019 study by the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy finds that efforts to put a price on greenhouse gas emissions are growing in North America.[18] In 2021, shipowners said they were against being included in the EU ETS.[19]

Economic aspects and tools

[edit]| Part of a series about |

| Environmental economics |

|---|

|

Economists generally agree that to regulate emissions efficiently, all polluters need to face the full marginal social costs of their actions.[20] Regulation of emissions applied only to one economic sector or region drastically reduces the efficiency of efforts to reduce global emissions.[21] There is, however, no scientific consensus over how to share the costs and benefits of reducing future climate change, or the costs and benefits of adapting to any future climate change.

Carbon offsets and credits

[edit]

Carbon offsetting is a carbon trading mechanism that enables entities to compensate for offset greenhouse gas emissions by investing in projects that reduce, avoid, or remove emissions elsewhere. When an entity invests in a carbon offsetting program, it receives carbon credit or offset credit, which account for the net climate benefits that one entity brings to another. After certification by a government or independent certification body, credits can be traded between entities. One carbon credit represents a reduction, avoidance or removal of one metric tonne of carbon dioxide or its carbon dioxide-equivalent (CO2e).

A variety of greenhouse gas reduction projects can qualify for offsets and credits depending on the scheme. Some include forestry projects that avoid logging and plant saplings,[22][23] renewable energy projects such as wind farms, biomass energy, biogas digesters, hydroelectric dams, as well as energy efficiency projects. Further projects include carbon dioxide removal projects, carbon capture and storage projects, and the elimination of methane emissions in various settings such as landfills. Many projects that give credits for carbon sequestration have received criticism as greenwashing because they overstated their ability to sequester carbon, with some projects being shown to actually increase overall emissions.[24][25][26][27]

Carbon offset and credit programs provide a mechanism for countries to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) commitments to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement.[28] Article 6 of the Paris Agreement includes three mechanisms for "voluntary cooperation" between countries towards climate goals, including carbon markets. Article 6.2 enabled countries to directly trade carbon credits and units of renewable power with each other. Article 6.4 established a new international carbon market allowing countries or companies to use carbon credits generated in other countries to help meet their climate targets.

Carbon offset and credit programs are coming under increased scrutiny because their claimed emissions reductions may be inflated compared to the actual reductions achieved.[29][30][31] To be credible, the reduction in emissions must meet three criteria: they must last indefinitely, be additional to emission reductions that were going to happen anyway, and must be measured and monitored to assure the that the amount of reduction promised has in fact been attained.[32]Carbon leakage

[edit]A domestic carbon emissions trading scheme is constrained in its regulatory jurisdiction. GHG emissions may thus leak to another region or sector with less regulation. Generally, leakages reduce the effectiveness of domestic emission abatement efforts. Notwithstanding, leakages may also be negative in nature, increasing the effectiveness of domestic abatement efforts.[33] For example, a carbon tax applied only to developed countries might lead to a positive leakage to developing countries.[34] However, a negative leakage might also occur due to technological developments driven by domestic regulation of GHGs,[35] helping to reduce emissions even in less regulated regions.

The current state of carbon emissions trading shows that roughly 22% of global greenhouse emissions are covered by 64 carbon taxes and emission trading systems as of 2021.[36] Energy intensive industries that are covered by such instruments may view the regulatory disparity between jurisdictions as a loss of competitiveness. They may therefore make strategic production decisions that involve carbon leakage. To mitigate carbon leakage and its effects on the environment, policymakers need to harmonize international climate policies and provide incentives to prevent companies from relocating production to regions with more lenient environmental regulations.[37]

Free emission permits, given to sectors vulnerable to international competition, are one way of addressing carbon leakage[38] by acting as a subsidy for the sector in question. The Garnaut Climate Change Review considered the free allocation of permits unjustified in any circumstances, arguing that governments could deal with market failure or claims for compensation more transparently with the revenue from full auctioning of permits.[39]

Border Adjustment

[edit]Another economically efficient solution to carbon leakage is border adjustment,[40] where tariffs are set on imported goods from less regulated countries. A problem with border adjustments is that they might be used as a disguise for trade protectionism.[41] Some types of border adjustment may also not prevent emissions leakage. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism takes in effect for 6 sectors in 2026.[42]

Potential global carbon market

[edit]The Paris Agreement provided a legal base for the creation of a global carbon market, which has a potentially significant role in stopping climate change.[43] In the beginning of 2024, the idea made some progress, as in the Bonn meeting new tools and supervisory bodies was created.[44]

The rules of the European Union Emissions Trading System include the possibility of connecting it with other trading systems. This has already happened with the Switzerland emissions trading system.[43][45] China expressed a support for a global carbon market, saying it is better than the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.[46]

In 2023 the global value of carbon markets was $948.75 billion.[47] It is expected to reach 2.68 trillion dollars by 2028 [48] and 22 trillion by 2050.[49]

Allocation of permits

[edit]Tradable emissions permits can be issued to firms within an ETS by two main ways: by free allocation of permits to existing emitters or by auction.[50] In the first case, the government receives no carbon revenue. In the second it receives the full value of the permits, on average. In either case, permits will be equally scarce and just as valuable to market participants, such that the price at sale will be the same in either case.[citation needed]

Generally, emitters will profit from permits allocated to them for free. But if they must pay, their profits will be reduced. If the carbon price equals the true social cost of carbon, then long-run profit reduction will reflect the consequences of paying this new cost. If having to pay this cost is unexpected, then there will likely be a one-time loss due to the change in regulations and not simply due to paying the real cost of carbon. However, if there is advanced notice of this change, or if the carbon price is introduced gradually, this one-time regulatory cost will be minimized. There has now been enough advance notice of carbon pricing that this effect should be negligible on average.[citation needed]

Grandfathering

[edit]Allocating permits based on past emissions is called "grandfathering".[51] Grandfathering permits can lead to perverse incentives, such as a firm being given fewer permits in the future for aiming to cut emissions drastically.[52] Another method of grandfathering is to base allocations on current production of economic goods rather than historical emissions. Under this method of allocation, the government will set a benchmark level of emissions for each good deemed to be sufficiently trade exposed and allocate firms units based on their production of this good. However, allocating permits in proportion to output implicitly subsidises production.[53]

The Garnaut Climate Change Review noted that grandfathered permits are not free of cost. As the permits are scarce, they have value, and the benefit of that value is acquired in full by the emitter. The cost is imposed elsewhere in the economy, typically on consumers who cannot pass on the costs:[39] The cost of a grandfathered permit may be regarded as the opportunity cost of not selling the permit at full value.[54] As a result, profit-maximising firms receiving free permits will raise prices to customers because of the new, non-zero cost of emissions.[55] This gives permit-liable polluters an incentive to reduce their emissions. However, if a firm sells the same amount of output as before that cap, with no change in production technology, the full value of permits received for free becomes windfall profits.[54] However, since the cap reduces output and often causes the company to incur costs to increase efficiency, windfall profits will be less than the full value of its free permits.

Grandfathering may also slow down technological development towards less polluting technologies.[56] The Garnaut Report noted that any method for free permit allocation will have the disadvantages of high complexity, high transaction costs, value-based judgements, and the use of arbitrary emissions baselines.[39] Garnaut also noted that the complexity of free allocation and the large amounts of money involved encourage non-productive rent-seeking behaviour and lobbying of governments — activities that dissipate economic value.[39]

At the same time, allocating permits can be used as a measure to protect domestic firms who are internationally exposed to competition.[57] This happens when domestic firms compete against other firms that are not subject to the same regulation. This argument in favor of allocation of permits has been used in the EU ETS, where industries that have been judged to be internationally exposed have been given permits for free.[58]

The International Air Transport Association, whose 230 member airlines comprise 93% of all international traffic, argue that emissions levels should be based on industry averages rather than using individual companies' previous emissions levels to set their future permit allowances, stating that "would penalise airlines that took early action to modernise their fleets, while a benchmarking approach, if designed properly, would reward more efficient operations".[59]

Auctioning

[edit]Hepburn et al. state that, empirically, businesses tend to oppose auctioning of emissions permits, while economists almost uniformly recommend auctioning permits.[60] Auctioning permits provides the government with revenues, which can be used to fund low-carbon investment and cuts in distortionary taxes.[61][62] Auctioning permits can therefore be more efficient and equitable than allocating permits.[63] Garnaut stated that full auctioning will provide greater transparency and accountability and lower implementation and transaction costs as governments retain control over the permit revenue.[39] Auctions of units are more flexible in distributing costs, provide more incentives for innovation, lessen the political arguments over the allocation of economic rents, and reduce tax distortions.[64] Recycling of revenue from permit auctions could also offset a significant proportion of the economy-wide social costs of a cap and trade scheme.[65]

The perverse incentive of grandfathering can be alleviated through auctioning.[57]

Permit supply level

[edit]Regulatory agencies run the risk of issuing too many emission credits, which can result in a very low price on emission permits.[66] This reduces the incentive that permit-liable firms have to cut back their emissions. On the other hand, issuing too few permits can result in an excessively high permit price.[57] An argument has been made for a hybrid instrument having a price floor and a price ceiling. However, a price-ceiling safety value removes the certainty of a particular quantity limit of emissions.[67]

Criticisms

[edit]

Emissions trading has been criticized for a variety of reasons. For one, it has been argued that climate change requires more radical solutions than pollution trading schemes, and that systemic changes must be made to reduce fossil fuel usage.[69][70] At the same time, carbon credits have been seen as enabling large companies to pollute the environment at the expense of local communities.[69] Carbon trading has also been criticised as a form of colonialism, in which rich countries maintain their levels of consumption while getting credit for carbon savings in inefficient industrial projects.[71]

Groups such as the Corner House have argued that the market will choose the easiest means to save a given quantity of carbon in the short term, which may be different from the means to reduce climate change.[citation needed] In September 2010, campaigning group FERN released "Trading Carbon: How it works and why it is controversial"[72][full citation needed] which compiles many of the arguments against carbon trading. According to Carbon Trade Watch, carbon trading has had a "disastrous track record". The effectiveness of the EU ETS was criticized, and it was argued that the CDM had routinely favoured "environmentally ineffective and socially unjust projects".[73]

Some groups have claimed that non-existent emission reductions can be recorded under the Kyoto Protocol due to the surplus of allowances that some countries possess. For example, Russia had a surplus of allowances due to its economic collapse following the end of the Soviet Union.[71] Other countries could have bought these allowances from Russia, but this would not have reduced emissions. In practice, as of 2010, Kyoto Parties had not yet chosen not to buy these surplus allowances.[74]

The complexity of cap and trade schemes around the world has resulted in the uncertainties around such schemes in Australia, Canada, China, the EU, India, Japan, New Zealand, and the US. As a result, some organizations have had little incentive to innovate and comply, resulting in an ongoing battle of stakeholder contestation for the past two decades.[75]

Proposals for alternative schemes to avoid the problems of cap-and-trade schemes include Cap and Share,[clarification needed] which was considered by the Irish Parliament in 2008, and the Sky Trust schemes.[76]

Carbon emission trading without border adjustments for exports leads to reduced global competitiveness for carbon-intensive products.[77]

Abuses

[edit]The Financial Times published an article about cap-and-trade systems, which argued that "Carbon markets create a muddle" and "...leave much room for unverifiable manipulation".[78] Emissions trading schemes have also been criticised for the potential of creating a new speculative market through the commodification of environmental risks through financial derivatives.[79][clarification needed]

Annie Leonard's 2009 documentary The Story of Cap and Trade criticized carbon emissions trading for the free permits to major polluters giving them unjust advantages, cheating in connection with carbon offsets, and as a distraction from the search for other solutions.[80]

In China, some companies started artificial production of greenhouse gases with sole purpose of recycling and gaining carbon credits. Similar practices happened in India. Earned credit were then sold to companies in US and Europe.[81][82]

Corporate and governmental carbon emission trading schemes have been modified in ways that have been attributed to permitting money laundering to take place.[83][84]

Examples by country

[edit]Australia

[edit]In 2003 the New South Wales (NSW) state government unilaterally established the New South Wales Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme[85] to reduce emissions by requiring electricity generators and large consumers to purchase NSW Greenhouse Abatement Certificates (NGACs). This has prompted the rollout of free energy-efficient compact fluorescent lightbulbs and other energy-efficiency measures, funded by the credits. This scheme has been criticised by the Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM) of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) because of its lack of effectiveness in reducing emissions, its lack of transparency and its lack of verification of the additionality of emission reductions.[86]

Prior to the 2007 federal election, both the incumbent Howard Coalition government and the Rudd Labor opposition promised to implement an emissions trading scheme (ETS). Labor won the election, and the new government proceeded to implement an ETS. The new Rudd government introduced the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme, which the Liberal Party of Australia (now led by Malcolm Turnbull) supported. Tony Abbott questioned an ETS, advocating a "simple tax" as the best way to reduce emissions.[87] Shortly before the carbon vote, Abbott defeated Turnbull in a leadership challenge (1 December 2009), and from there on the Liberals opposed the ETS. This left the Rudd Labor government unable to secure passage of the bill, and it was subsequently withdrawn.

Julia Gillard defeated Rudd in a leadership challenge, becoming Federal Prime Minister in June 2010. She promised that she would not introduce a carbon tax, but would look to legislate a price on carbon[88] when taking the government to the 2010 election. In the first Australian hung-parliament result in 70 years, the Gillard Labor government required the support of crossbenchers - including the Greens. One requirement for Greens' support was a carbon price, which Gillard proceeded with in forming a minority government. A fixed carbon-price would proceed to a floating-price ETS within a few years under the plan. The fixed price lent itself to characterisation as a "carbon tax", and when the government proposed the Clean Energy Bill in February 2011,[89] the opposition denounced it as a broken election promise.[90]

The Lower House passed the bill in October 2011[91] and the Upper House in November 2011.[92] The Liberal Party vowed to repeal the bill if elected.[93] The bill thus resulted in passage of the Clean Energy Act, which possessed a great deal of flexibility in its design and uncertainty over its future.

The Liberal/National coalition government elected in September 2013 promised to reverse the climate legislation of the previous government.[94] In July 2014, the carbon tax was repealed - as well as the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) that was to start in 2015.[95]

Canada

[edit]The Canadian provinces of Quebec and Nova Scotia operate an emissions trading scheme. Quebec links its program with the US state of California through the Western Climate Initiative.

China

[edit]The Chinese national carbon trading scheme is the largest in the world. It is an intensity-based trading system for carbon dioxide emissions by China, which started operating in 2021.[96] The initial design of the system targets a scope of 3.5 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions that come from 1700 installations.[97] It has made a voluntary pledge under the UNFCCC to lower CO2 per unit of GDP by 40–45% in 2020 when comparing to the 2005 levels.[98]

In November 2011, China approved pilot tests of carbon trading in seven provinces and cities—Beijing, Chongqing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Tianjin, as well as Guangdong Province and Hubei Province, with different prices in each region.[99] The pilot is intended to test the waters and provide valuable lessons for the design of a national system in the near future. Their successes or failures will, therefore, have far-reaching implications for carbon market development in China in terms of trust in a national carbon trading market. Some of the pilot regions can start trading as early as 2013/2014.[100] National trading is expected to start in 2017, latest in 2020.

The effort to start a national trading system has faced some problems that took longer than expected to solve, mainly in the complicated process of initial data collection to determine the base level of pollution emission.[101] According to the initial design, there will be eight sectors that are first included in the trading system: chemicals, petrochemicals, iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, building materials, paper, power and aviation, but many of the companies involved lacked consistent data.[97] Therefore, by the end of 2017, the allocation of emission quotas have started but it has been limited to only the power sector and will gradually expand, although the operation of the market is yet to begin.[102] In this system, Companies that are involved will be asked to meet target level of reduction and the level will contract gradually.[97]

European Union

[edit]

The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is a carbon emission trading scheme (or cap and trade scheme) that began in 2005 and is intended to lower greenhouse gas emissions in the EU. Cap and trade schemes limit emissions of specified pollutants over an area and allow companies to trade emissions rights within that area. The ETS covers around 45% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions.[103]

As from 2027 road transport and buildings and industrial installation that fell out of EU ETS will be covered by a new EU ETS2. The "old" ETS and the new EU ETS2 allowances will be traded independently. A major difference to the ETS is that ETS2 will cover the CO2 emissions upstream - whereby accredited fuel suppliers who places the fuel on the EU market will be obliged to cover that fuel with ETS2 emission allowances. The ETS2 covers around 40% of the EU's greenhouse gas emissions.

The scheme has been divided into four "trading periods". The first ETS trading period lasted three years, from January 2005 to December 2007. The second trading period ran from January 2008 until December 2012, coinciding with the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol. The third trading period lasted from January 2013 to December 2020. Compared to 2005, when the EU ETS was first implemented, the proposed caps for 2020 represent a 21% reduction of greenhouse gases. This target was achieved six years early as emissions in the ETS fell to 1.812 billion (109) tonnes in 2014.[104]

The fourth phase started in January 2021 and will continue until December 2030. The emission reductions to be achieved over this period are unclear as of November 2021, as the European Green Deal necessitates tightening of the current EU ETS reduction target for 2030 of -43% concerning to 2005. The EU Commission proposes in its "Fit for 55" package to increase the EU ETS reduction target for 2030 to −61% compared to 2005.[105][106]

EU countries view the emissions trading scheme as necessary for meeting climate goals. A strong carbon market guides investors and industry in their transition from fossil fuels.[107] A 2020 study found that the EU ETS successfully reduced CO2 emissions even though the prices for carbon were set at low prices.[108] A review of 13 policy evaluations quantifies this emission reduction effect at 7%.[109] A 2023 study on the effects of the EU ETS identified a reduction in carbon emissions in the order of -10% between 2005 and 2012 with no impacts on profits or employment for regulated firms.[110] The price of EU allowances exceeded 100€/tCO2 ($118) in February 2023.[107] A 2024 study further demonstrated that the EU ETS has incidentally contributed to reduce atmospheric levels of air pollutants in the EU including sulfur dioxide, fine particulate matter, and nitrogen oxide.[111] This reduction has translated in local health co-benefits, alongside the system's primary goal of mitigating climate change.India

[edit]Trading is set to begin in 2014 after a three-year rollout period. It is a mandatory energy efficiency trading scheme covering eight sectors responsible for 54 per cent of India's industrial energy consumption. India has pledged a 20 to 25 per cent reduction in emission intensity from 2005 levels by 2020. Under the scheme, annual efficiency targets will be allocated to firms. Tradable energy-saving permits will be issued depending on the amount of energy saved during a target year.[100][needs update]

Japan

[edit]Japan as a country does not have a compulsory emissions trading scheme. The government in 2010 (the Hatoyama cabinet) had planned to introduce one, but the plan lost momentum after Hatoyama resigned as prime minister, due partly from industrial opposition,[112] and was eventually shelved. Japan has a voluntary scheme. Furthermore, the Kyoto Prefecture has a voluntary emissions trading scheme.[113]

Two regional mandatory schemes exist however, in Tokyo and Saitama Prefecture. The city of Tokyo consumes as much energy as "entire countries in Northern Europe, and its production matches the GNP of the world's 16th largest country". A cap-and-trade carbon trading scheme launched in April 2010 covers the top 1,400 emitters in Tokyo, and is enforced and overseen by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.[114] Phase 1, which was similar to Japan's voluntary scheme, ran until 2015.[115] Emitters had to cut their emissions by 6% or 8% depending on the type of organization; from 2011, those who exceed their limits were required to buy matching allowances, or invest in renewable-energy certificates, or offset credits issued by smaller businesses or branch offices.[116] Polluters that failed to comply were liable up to 500,000 yen in fines plus credits for 1.3 times excess emissions.[117] In its fourth year, emissions were reduced by 23% compared to base-year emissions.[118] In phase 2 (FY2015–FY2019), the target was expected to increase to 15–17%. The aim was to cut Tokyo's carbon emissions by 25% from 2000 levels by 2020.[116]

One year after Tokyo launched its cap-and-trade scheme, the neighbouring Saitama Prefecture launched a highly similar scheme. The two schemes are connected.[113]

New Zealand

[edit]

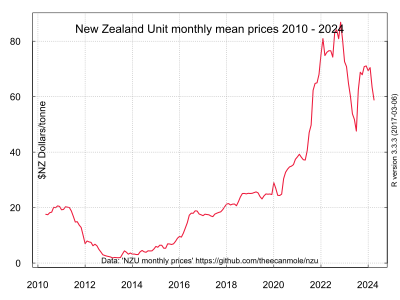

The New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (NZ ETS) is an all-gases partial-coverage uncapped domestic emissions trading scheme that features price floors, forestry offsetting, free allocation and auctioning of emissions units.

The NZ ETS was first legislated in the Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act 2008 in September 2008 under the Fifth Labour Government of New Zealand[119][120] and then amended in November 2009[121] and in November 2012[122] by the Fifth National Government of New Zealand.

The NZ ETS was until 2015 highly linked to international carbon markets as it allowed unlimited importing of most of the Kyoto Protocol emission units. There is a domestic emission unit; the 'New Zealand Unit' (NZU), which was initially issued by free allocation to emitters until auctions of units commenced in 2020.[123] The NZU is equivalent to 1 tonne of carbon dioxide. Free allocation of units varies between sectors. The commercial fishery sector (who are not participants) received a one-off free allocation of units on a historic basis.[124] Owners of pre-1990 forests received a fixed free allocation of units.[125] Free allocation to emissions-intensive industry,[126][127] is provided on an output-intensity basis. For this sector, there is no set limit on the number of units that may be allocated.[128][129] The number of units allocated to eligible emitters is based on the average emissions per unit of output within a defined 'activity'.[130] Bertram and Terry (2010, p 16) state that as the NZ ETS does not 'cap' emissions, the NZ ETS is not a cap and trade scheme as understood in the economics literature.[131]

Some stakeholders have criticised the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme for its generous free allocations of emission units and the lack of a carbon price signal (the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment),[132] and for being ineffective in reducing emissions (Greenpeace Aotearoa New Zealand).[133]South Korea

[edit]South Korea's national emissions trading scheme officially launched on January 1, 2015, covering 525 entities from 23 sectors. With a three-year cap of 1.8687 billion tCO2e, it now forms the second-largest carbon market in the world, following the EU ETS. This amounts to roughly two-thirds of the country's emissions. The Korean emissions trading scheme is part of the Republic of Korea's efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 30% compared to the business-as-usual scenario by 2020.[118]

United Kingdom

[edit]United States

[edit]The American Clean Energy and Security Act (H.R. 2454), a greenhouse gas cap-and-trade bill, was passed on 26 June 2009 in the House of Representatives by a vote of 219–212. The bill originated in the House Energy and Commerce Committee. It was introduced by Representatives Henry A. Waxman and Edward J. Markey.[137] The political advocacy organizations FreedomWorks and Americans for Prosperity, funded by brothers David and Charles Koch of Koch Industries, encouraged the Tea Party movement to focus on defeating the legislation.[138][139] Although cap and trade also gained a significant foothold in the Senate via the efforts of Republican Lindsey Graham, Independent and former Democrat Joe Lieberman, and Democrat John Kerry,[140] the legislation died in the Senate.[141]

President Barack Obama's proposed 2010 United States federal budget wanted to support clean energy development with a 10-year investment of US$15 billion per year, generated from the sale of greenhouse gas emissions credits. Under the proposed cap-and-trade program, all GHG emissions credits would have been auctioned off, generating an estimated $78.7 billion in additional revenue in FY 2012, steadily increasing to $83 billion by FY 2019.[142] The proposal was never made law. Failing to get congressional approval for such a scheme, President Barack Obama instead acted through the United States Environmental Protection Agency to attempt to adopt the Clean Power Plan, which does not feature emissions trading. The plan was subsequently challenged by the administration of President Donald Trump.

In 2021, Washington state instituted its own emissions trading system, which it called "cap-and-invest." Revenue from the auctioning of carbon allowances is directly invested in programs intended to address climate change.

In the United States, most polling shows large support for emissions trading.[143][144][145][146]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Emissions Trading Worldwide: Status Report 2021". Berlin: International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP). Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Olivier, J.G.J.; Peters, J.A.H.W. (2020). "Trends in global CO2 and total greenhouse gas emissions (2020)" (PDF). The Hague: PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

- ^ "Policy Brief: EU emissions trading". Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change. Archived from the original on March 2, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ Yuan, Lin (July 22, 2021). "China's national carbon market exceeds expectations". Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ "Carbon Price Viewer". EMBER. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ IMF (March 2008). "Fiscal Implications of Climate Change" (PDF). International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Affairs Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Halsnæs, K.; et al. (2007). "2.4 Cost and benefit concepts, including private and social cost perspectives and relationships to other decision-making frameworks". In B. Metz; et al. (eds.). Framing issues. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y., U.S.A. p. 6. Archived from the original on May 2, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Toth, F.L.; et al. (2005). "10.1.2.2 The Problem Is Long Term.". In B. Metz; et al. (eds.). Decision-making Frameworks. Climate Change 2005: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: GRID-Arendal website. Archived from the original on December 7, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ Goldemberg, J.; et al. (1996). "Introduction: scope of the assessment.". In J.P. Bruce; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-56854-8.

- ^ Tietenberg, Tom (2003). "The Tradable-Permits Approach to Protecting the Commons: Lessons for Climate Change". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 19 (3): 400–419. doi:10.1093/oxrep/19.3.400.

- ^ David M. Driesen. "Capping Carbon". Environmental Law. 40 (1): 1–55.

Setting the cap properly matters more to environmental protection than the decision to allow, or not allow, trades

- ^ "Tax Treaty Issues Related to Emissions Permits/Credits" (PDF). OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ "Key points: Update Paper 6: Carbon pricing and reducing Australia's emissions". Garnaut Climate Change Review. March 17, 2011. Archived from the original on April 21, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- ^ Grimeaud, D, 'An overview of the policy and legal aspects of the international climate change regime' (2001) 9(2) Environmental Liability 39.

- ^ Stewart, R, "Economic incentives for environmental protection: opportunities and obstacles", in Revesz, R; Sands, P; Stewart, R (eds.), Environment Law, the Economy and Sustainable Development, 2000, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "China's carbon market scheme too limited, say analysts". Financial Times. July 16, 2021. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "Study: EU emission trading system makes coal more expensive". CompressorTECH2. June 24, 2021. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ "State and Provincial Efforts to Put a Price on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, with Implications for Energy Efficiency". ACEEE. January 2, 2019. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^ Meredith, Sam (July 12, 2021). "The world's largest carbon market is set for a historic revamp. Europe's shipowners are concerned". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ Goldemburg et al., 1996, pp. 29, 37

- ^ Goldemburg et al., 1996, p. 30

- ^ a b Hamrick, Kelley; Gallant, Melissa (May 2017). "Unlocking Potential: State of the Voluntary Carbon Markets 2017" (PDF). Forest Trends' Ecosystem Marketplace. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ Haya, Barbara K.; Evans, Samuel; Brown, Letty; Bukoski, Jacob; Butsic, Van; Cabiyo, Bodie; Jacobson, Rory; Kerr, Amber; Potts, Matthew; Sanchez, Daniel L. (March 21, 2023). "Comprehensive review of carbon quantification by improved forest management offset protocols". Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 6. Bibcode:2023FrFGC...6.8879H. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2023.958879. ISSN 2624-893X.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (January 18, 2023). "Revealed: more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets by biggest certifier are worthless, analysis shows". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Blake, Heidi (October 16, 2023). "The Great Cash-for-Carbon Hustle". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Greenfield, Patrick (August 24, 2023). "Carbon credit speculators could lose billions as offsets deemed worthless". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Masie, Desné (August 3, 2023). "Are carbon offsets all they're cracked up to be? We tracked one from Kenya to England to find out". Vox. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "Climate Explainer: Article 6". World Bank. Retrieved March 29, 2023.

- ^ "Goldman School of Public Policy | Goldman School of Public Policy | University of California, Berkeley". gspp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Probst, Benedict; Toetzke, Malte; Anadon, Laura Diaz; Kontoleon, Andreas; Hoffmann, Volker (July 27, 2023). Systematic review of the actual emissions reductions of carbon offset projects across all major sectors (Report). In Review. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3149652/v1. hdl:20.500.11850/620307.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Carbon offsets and credits :1was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hawken, Paul, ed. (2021). Regeneration: ending the climate crisis in one generation. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-313697-2.

- ^ IPCC (2007). "Glossary A-D". In B. Metz; et al. (eds.). Annex I: Glossary. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Goldemberg et al., 1996, pp. 27–28

- ^ Barker, T.; et al. (2007). "Executive Summary". In B. Metz; et al. (eds.). Mitigation from a cross-sectoral perspective. Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Print version: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A.. This version: IPCC website. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010.

- ^ World Bank. (2021, May 25). State and trends of carbon pricing 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35620

- ^ Carbon Market Watch. (2017). Carbon Leakage: A short history of an industry lobbying buzzword. Retrieved from https://carbonmarketwatch.org/2017/02/28/carbon-leakage-a-short-history-of-an-industry-lobbying-buzzword/

- ^ Carbon Trust (March 2009). "Memorandum submitted by The Carbon Trust (ET19)". The role of carbon markets in preventing dangerous climate change. Minutes of Evidence, Tuesday 21 April 2009. UK Parliament House of Commons Environmental Audit Select Committee. The fourth report of the 2009-10 session. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Garnaut, Ross (2008). "Releasing permits into the market". The Garnaut Climate Change Review. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74444-7. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Neuhoff, K. (February 22, 2009). "Memorandum submitted by Karsten Neuhoff, Assistant Director, Electric Policy Research Group, University of Cambridge". The role of carbon markets in preventing dangerous climate change. Written evidence. UK Parliament House of Commons Environmental Audit Select Committee. The fourth report of the 2009-10 session. Retrieved May 1, 2010.<ref>Newbery, D. (February 26, 2009). "Memorandum submitted by David Newbery, Research Director, Electric Policy Research Group, University of Cambridge". The role of carbon markets in preventing dangerous climate change. Written evidence. UK Parliament House of Commons Environmental Audit Select Committee. The fourth report of the 2009-10 session. Retrieved April 30, 2010.</ ref>

- ^ Grubb, M.; et al. (August 3, 2009). "Climate Policy and Industrial Competitiveness: Ten Insights from Europe on the EU Emissions Trading System". Climate Strategies: 5. Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- ^ "cbam regulation". EUR-Lex. May 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "International carbon market". European Commission. European Union. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Jardine, Chloe (March 4, 2024). "Paris agreement carbon crediting mechanism advances". Argus. Retrieved March 5, 2024.

- ^ Vaughan, Scott; Di Leva, Charles. "Will International Carbon Markets Finally Deliver?". International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ "China Objects to EU's Border Carbon Tax, Backs Global Market". BNN Bloomberg. February 26, 2024. Retrieved February 27, 2024.

- ^ Twidale, Susanna (February 12, 2024). "Global carbon markets value hit record $949 bln last year - LSEG". Reuters. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "Global Carbon Credit Market 2023: Sector to Reach $2.68 Trillion by 2028 at a CAGR of 18.23%". Yahoo. April 19, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ McFarlane, Sarah (September 1, 2023). "Energy Traders See Big Money in Carbon-Emissions Markets". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ Gupta, S.; et al. (2007), "Section 13.2.1.3 Tradable permits", in B. Metz; et al. (eds.), Chapter 13: Policies, instruments, and co-operative arrangements, Climate Change 2007: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A., retrieved July 10, 2010

- ^ Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 38

- ^ "Fiscal Implications of Climate Change" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. March 2008. pp. 25–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Fischer, C; Fox, A (2007). "Output-based allocation of emissions permits for mitigating tax and trade interactions" (PDF). Land Economics. 83 (4): 575–599. doi:10.3368/le.83.4.575. S2CID 55649597. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 17, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

However, there often are important trade-offs in terms of efficiency because OBA implicitly subsidizes production, unlike conventional lump-sum allocation mechanisms like grandfathering.

- ^ a b Don Fullerton & Gilbert E. Metcalf (1997). "Environmental Taxes and the Double-Dividend Hypothesis" (PDF). NBER. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2014.

- ^ Goulder, Lawrence H.; Pizer, William A. (2006). The Economics of Climate Change (PDF). DP 06-06. Resources for the Future. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 26, 2006.

- ^ Fisher, B.S.; et al. (1996). "An Economic Assessment of Policy Instruments for Combating Climate Change.". In J.P. Bruce; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York, N.Y., U.S.A. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-521-56854-8.

- ^ a b c Hepburn, C. (2006). "Regulating by prices, quantities or both: an update and an overview" (PDF). Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 22 (2): 236–239. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grj014. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2009. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Cambridge Centre for Climate Change Mitigation Research (June 19, 2008). "The Revision of the EU's Emissions Trading System". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ "What You Need to Know About Emissions Trading" (PDF). International Air Transport Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2009.

- ^ Hepburn, Cameron J; Neuhoff, Karsten; Grubb, Michael; Matthes, Felix; Tse, Max (2006). "Auctioning of EU ETS Phase II allowances: why and how?" (PDF). Climate Policy. 6 (1): 137–160. doi:10.3763/cpol.2006.0608. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ "Climate change; The greening of America". The Economist. January 25, 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Fisher, B.S.; et al. (1996). "An Economic Assessment of Policy Instruments for Combating Climate Change" (PDF). In J.P. Bruce; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 1995: Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Second Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-521-56854-8.

- ^ Hepburn, C. (2006). "Regulating by prices, quantities or both: an update and an overview" (PDF). Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 22 (2): 226–247. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grj014. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Kerr, Suzi; Cramton, Peter (1998). "Tradable Carbon Permit Auctions: How and Why to Auction Not Grandfather" (PDF). Discussion Paper Dp-98-34. Resources For the Future. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 26, 2003.

An auction is preferred to grandfathering (giving companies permits based on historical output or emissions), because it allows reduced tax distortions, provides more flexibility in distribution of costs, provides greater incentives for innovation, and reduces the need for politically contentious arguments over the allocation of rents.

- ^ Stavins, Robert N. (2008). "Addressing climate change with a comprehensive US cap-and-trade system" (PDF). Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 24 (2 24): 298–321. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grn017. hdl:10419/53231. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 10, 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 4: Carbon markets and carbon price". Building a low-carbon economy – The UK's contribution to tackling climate change. Committee on Climate Change. December 2008. pp. 140–149. Archived from the original on May 25, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Bashmakov, I.; et al. (2001). "6. Policies, Measures, and Instruments". In B. Metz; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2001: Mitigation. Contribution of Working Group III to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC. Archived from the original on August 5, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2021, World Bank, May 25, 2021, archived from the original on July 16, 2021, retrieved July 7, 2021

- ^ a b Lohmann, Larry (December 5, 2006). "A licence to carry on polluting?". New Scientist. 2580. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2010. Alt URL Archived 2011-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carbon Trade Watch". Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ a b Liverman, D.M. (2008). "Conventions of climate change: constructions of danger and the dispossession of the atmosphere" (PDF). Journal of Historical Geography. 35 (2): 279–296. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2008.08.008. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 4, 2009. Retrieved August 8, 2009.

- ^ "Trading Carbon". Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ Carbon Trade Watch (November 2009). "Carbon Trading – How it works and why it fails". Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ PBL (October 16, 2009). "Industrialised countries will collectively meet 2010 Kyoto target". Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) website. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Teeter, Preston; Sandberg, Jorgen (2016). "Constraining or Enabling Green Capability Development? How Policy Uncertainty Affects Organizational Responses to Flexible Environmental Regulations" (PDF). British Journal of Management. 28 (4): 649–665. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12188. S2CID 157986703. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Ray Barrell, Alan Barrett, Noel Casserly, Frank Convery, Jean Goggin, Ide Kearney, Simon Kirby, Pete Lunn, Martin O'Brien and Lisa Ryan. 2009. Budget Perspectives, Tim Callan (ed.)

- ^ Evans, Stuart; Mehling, Michael A.; Ritz, Robert A.; Sammon, Paul (March 16, 2021). "Border carbon adjustments and industrial competitiveness in a European Green Deal". Climate Policy. 21 (3): 307–317. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1856637. ISSN 1469-3062.

- ^ "Carbon markets create a muddle". Financial Times. April 26, 2007. Archived from the original on May 7, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Larry Lohmann: Uncertainty Markets and Carbon Markets. Variations on Polanyian Themes, New Political Economy, first published August 2009, abstract Archived February 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and full text Archived December 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Annie Leonard (2009). "The Story of Cap and Trade". The Story of Stuff Project. Archived from the original on November 3, 2010. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ "Carbon-Credits System Tarnished by WikiLeaks Revelation". Scientific American. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Imminent EU proposals to clamp down on fridge gas scam". November 24, 2010. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ "Carbon trading used as money-laundering front: experts" www.saigon-gpdaily.com.vn Archived August 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ I. Lippert. Enacting Environments: An Ethnography of the Digitalisation and Naturalisation of Emissions Archived January 17, 2023, at the Wayback Machine. University of Augsburg, 2013.

- ^ "The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme". NSW: Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme Administrator. January 4, 2010. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ Passey, Rob; MacGill, Iain; Outhred, Hugh (2007). "The NSW Greenhouse Gas Reduction Scheme: An analysis of the NGAC Registry for the 2003, 2004 and 2005 Compliance Periods" (PDF). CEEM discussion paper DP_070822. Sydney: The UNSW Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Thompson, Jeremy (June 7, 2011). "Abbott defends carbon tax interview". ABC News. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ "Julia Gillard's carbon price promise" Archived March 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, The Australian, 20 August 2010.

- ^ Leslie, Tim (February 24, 2011). "Gillard unveils Carbon Price Details". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Hudson, Phillip (February 26, 2011). "Tony Abbott calls for election on carbon tax". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2011.

- ^ Johnston, Matt (October 12, 2011). "Carbon tax bills pass lower house of federal Parliament". Herald Sun. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ AAP with Reuters (November 8, 2011). "Carbon tax gets green light in Senate". Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Opposition vows to repeal carbon tax". Sydney Morning Herald. October 2, 2011. Archived from the original on February 6, 2015. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "Abbott Government's first actions: trash climate change education, carbon pricing" Archived September 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Indymedia Australia, 20 September 2013. Accessed 8 November 2013.

- ^ "Carbon tax scrapped: PM Tony Abbott sees key election promise fulfilled after Senate votes for repeal". ABC News. July 7, 2014. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ "China National ETS". Archived from the original on June 3, 2019.

- ^ a b c "China Looks Towards Next Steps For Implementing National Carbon Market". ICTSD. January 18, 2018. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018.

- ^ "China could launch national carbon market in 2016". CLIMATE HOME. September 2014. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Andrews-Speed, Philip (November 2014). "China's Energy Policymaking Processes and Their Consequences". The National Bureau of Asian Research Energy Security Report. Archived from the original on July 22, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Factbox: Carbon trading schemes around the world". Reuters. July 11, 2011. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ Feng, Emily (December 19, 2017). "China moves towards launch of carbon trading scheme". Financial Times. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "China to Launch World's Largest Emissions Trading System". UNFCCC. December 19, 2017. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "EU Emissions Trading System".

- ^ "Transform -". www.environmentalistonline.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ European Commission (July 14, 2021). "Delivering the European Green Deal". Archived from the original on November 1, 2021. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ^ "EU Emissions Trading System reaches provisional agreement - SAFETY4SEA". March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Twidale, Susanna; Abnett, Kate; Chestney, Nina; Chestney, Nina (February 21, 2023). "EU carbon hits 100 euros taking cost of polluting to record high". Reuters. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Bayer, Patrick; Aklin, Michaël (April 2, 2020). "The European Union Emissions Trading System reduced CO2 emissions despite low prices". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (16): 8804–8812. Bibcode:2020PNAS..117.8804B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1918128117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7183178. PMID 32253304.

- ^ Döbbeling-Hildebrandt, Niklas; Miersch, Klaas; Khanna, Tarun M.; Bachelet, Marion; Bruns, Stephan B.; Callaghan, Max; Edenhofer, Ottmar; Flachsland, Christian; Forster, Piers M.; Kalkuhl, Matthias; Koch, Nicolas; Lamb, William F.; Ohlendorf, Nils; Steckel, Jan Christoph; Minx, Jan C. (May 16, 2024). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of ex-post evaluations on the effectiveness of carbon pricing". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 4147. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48512-w. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11099057. PMID 38755167.

- ^ Dechezleprêtre, Antoine; Nachtigall, Daniel; Venmans, Frank (March 1, 2023). "The joint impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon emissions and economic performance". Journal of Environmental Economics and Management. 118: 102758. Bibcode:2023JEEM..11802758D. doi:10.1016/j.jeem.2022.102758. ISSN 0095-0696.

- ^ Basaglia, Piero; Grunau, Jonas; Drupp, Moritz A. (July 9, 2024). "The European Union Emissions Trading System might yield large co-benefits from pollution reduction". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121 (28). doi:10.1073/pnas.2319908121. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 11252810.

- ^ Watanabe, Rie (January 1, 2012). "14. Northeast Asia: A. Japan". Yearbook of International Environmental Law. 23 (1): 454. doi:10.1093/yiel/yvt038. ISSN 0965-1721. Archived from the original on July 29, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ a b "Japan: Greenhouse gas emissions trading schemes | White & Case LLP". www.whitecase.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ China's Carbon Emission Trading Archived October 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 2012.

- ^ "Tokyo CO2 credit trading plan may become a model". Reuters. February 11, 2010. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Business Green (April 8, 2010). "Tokyo kicks off carbon trading scheme". The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved December 29, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Urban Environment and Climate Change – Publications". Archived from the original on January 24, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Emissions Trading Worldwide ICAP Status Report 2015" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Parker, David (September 10, 2008). "Historic climate change legislation passes" (Press release). New Zealand Government. Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- ^ "Climate Change Response (Emissions Trading) Amendment Act 2008 No 85". legislation.govt.nz. Parliamentary Counsel Office. September 25, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Hon Nick Smith (November 25, 2009). "Balanced new law important step on climate change" (Press release). New Zealand Government. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ "ETS Amendment Bill passes third reading" (Press release). New Zealand Government. November 9, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ "New Zealand Units (NZUs)". Climate change information New Zealand. Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government (www.climatechange.govt.nz). June 18, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

In the short term, the Government is unlikely to sell emission units because the Kyoto units allocated to New Zealand will be needed to support New Zealand's international obligations, as well as allocation to eligible sectors under the emissions trading scheme.

- ^ MfE (September 2009). "Summary of the proposed changes to the NZ ETS". Emissions trading bulletin No 11. Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ MfE (January 14, 2010). "How will the changes impact on forestry?". Questions and answers about amendments to the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government (www.climatechange.govt.nz). Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ "Who will get a free allocation of emission units?". Questions and answers about the emissions trading scheme. Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. January 14, 2010. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- ^ MfE (September 2009). "Agriculture". Summary of the proposed changes to the NZ ETS - Emissions Trading Bulletin 11. Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ MfE (September 1, 2009). "Emissions trading bulletin No 11: Summary of the proposed changes to the NZ ETS". Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ MfE (September 2009). "Industrial allocation update". Emissions trading bulletin No 12, INFO 441. Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. Retrieved August 8, 2010.

The Bill changes the allocation provisions of the existing CCRA from allocating a fixed pool of emissions to an uncapped approach to allocation. There is no longer an explicit limit on the number of New Zealand units (NZUs) that can be allocated to the industrial sector.

- ^ MfE (January 14, 2010). "How will free allocation of emission units to the industrial sector work now?". Questions and answers about amendments to the New Zealand Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Ministry for the Environment, NZ Government. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ Bertram, Geoff; Terry, Simon (2010). The Carbon Challenge: New Zealand's Emissions Trading Scheme. Bridget Williams Books, Wellington. ISBN 978-1-877242-46-5.

The New Zealand ETS does not fit this model because there is no cap and therefore no certainty as to the volume of emissions with which the national economy must operate

- ^ "New bill 'weakens ETS' says Environment Commissioner" (Press release). Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. October 15, 2009. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

The allocation of free carbon credits to industrial processes is extremely generous and removes the carbon price signal where New Zealand needs one the most

- ^ "Revised ETS an insult to New Zealanders" (Press release). Greenpeace New Zealand. September 14, 2009. Retrieved October 12, 2009.

We now have on the table a pathetic ETS which won't actually do anything to reduce emissions

- ^ "Policy briefing: Get ready for the UK's emissions trading scheme". www.endsreport.com. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Participating in the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (UK ETS), published 17 December 2021, accessed 15 January 2021

- ^ Ng, Gabriel (January 23, 2021). "Introducing the UK Emissions Trading System". Cherwell. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ "The American Clean Energy and Security Act (H.R. 2454)". Energycommerce.house.gov. June 1, 2009. Archived from the original on February 5, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2010.

- ^ Dryzek, John S.; Norgaard, Richard B.; Schlosberg, David (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Climate Change and Society. Oxford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780199683420.

- ^ Mayer, Jane (August 30, 2010). "Covert Operations: The billionaire brothers who are waging a war against Obama". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 21, 2022. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Lizza, Ryan (October 11, 2010). "As the World Burns: How the Senate and the White House missed their best chance to deal with climate change". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ Turin, Dustin R. (2012). "The Challenges of Climate Change Policy: Explaining the Failure of Cap and Trade in the United States With a Multiple-Streams Framework". Student Pulse. 4 (6). Archived from the original on May 25, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2021.

- ^ "President's Budget Draws Clean Energy Funds from Climate Measure". Renewable Energy World. Archived from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ "Majority of Poll Respondents Say U.S. Should Limit Greenhouse Gases Archived January 31, 2021, at the Wayback Machine", The Washington Post. 25 June 2009.

- ^ "Poll Position: New Zogby Poll Shows 71% Support for Waxman-Markey Archived July 31, 2020, at the Wayback Machine", The Wall Street Journal. 11 Aug. 2009

- ^ "Poll: Americans Support Strong Climate, Energy Policies", Yale Climate & Energy Institute Archived 2012-01-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "IBD editorial board claims that cap-and-trade is unpopular in America Archived May 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine", PolitiFact

External links

[edit]- The Stern Review on the economics of climate change – Chapters 14 and 15 have extensive discussions on emission trading schemes and carbon taxes

- Emissions Trading and CDM – International Energy Agency