Golden Age of Comic Books

| Golden Age of Comic Books | |

|---|---|

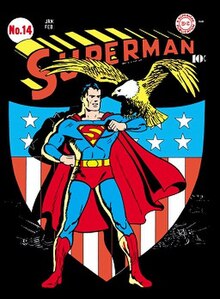

Superman, catalyst of the Golden Age: Superman #14 (Feb. 1942). Cover art by Fred Ray. | |

| Time span | may 1938 – August 1956 |

| Related periods | |

| Followed by | Silver Age of Comic Books |

The Golden Age of Comic Books describes an era of American comic books from 1938 to 1956. During this time, modern comic books were first published and rapidly increased in popularity. The superhero archetype was created and many well-known characters were introduced, including Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel (now known as Shazam), Captain America, and Wonder Woman.

Etymology

The first recorded use of the term "Golden Age" was by Richard A. Lupoff in an article, "Re-Birth", published in issue one of the fanzine Comic Art in April 1960.[1]

History

An event cited by many as marking the beginning of the Golden Age was the 1938 debut of Superman in Action Comics #1,[2] published by Detective Comics[3] (predecessor of DC Comics). Superman's popularity helped make comic books a major arm of publishing,[4] which led rival companies to create superheroes of their own to emulate Superman's success.[5][6]

World War II

Between 1939 and 1941 Detective Comics and its sister company, All-American Publications, introduced popular superheroes such as Batman and Robin, Wonder Woman, the Flash, Green Lantern, Doctor Fate, the Atom, Hawkman, Green Arrow and Aquaman.[7] Timely Comics, the 1940s predecessor of Marvel Comics, had million-selling titles featuring the Human Torch, the Sub-Mariner, and Captain America.[8] Although DC and Timely characters are well-remembered today, circulation figures suggest that the best-selling superhero title of the era was Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel with sales of about 1.4 million copies per issue. The comic was published biweekly at one point to capitalize on its popularity.[9]

Patriotic heroes donning red, white, and blue were particularly popular during the time of the second World War following The Shield's debut in 1940.[10] Many heroes of this time period battled the Axis powers, with covers such as Captain America Comics #1 (cover-dated March 1941) showing the title character punching Nazi leader Adolf Hitler.[11]

As comic books grew in popularity, publishers began launching titles that expanded into a variety of genres. Dell Comics' non-superhero characters (particularly the licensed Walt Disney animated-character comics) outsold the superhero comics of the day.[12] The publisher featured licensed movie and literary characters such as Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Roy Rogers and Tarzan.[13] It was during this era that noted Donald Duck writer-artist Carl Barks rose to prominence.[14] Additionally, MLJ's introduction of Archie Andrews in Pep Comics #22 (December 1941) gave rise to teen humor comics,[15] with the Archie Andrews character remaining in print well into the 21st century.[16]

At the same time in Canada, American comic books were prohibited importation under the War Exchange Conservation Act[17] which restricted the importation of non-essential goods. Canadian publishers responded to this lack of competition by producing titles of their own, informally called the Canadian Whites. While these titles flourished during the war, they did not survive the lifting of trade restrictions afterwards.

After the war

The educational comic book Dagwood Splits the Atom used characters from the comic strip Blondie.[18] According to historian Michael A. Amundson, appealing comic-book characters helped ease young readers' fear of nuclear war and neutralize anxiety about the questions posed by atomic power.[19] It was during this period that long-running humor comics debuted, including EC Comics's Mad and Carl Barks' Uncle Scrooge in Dell's Four Color Comics (both in 1952).[20][21]

In 1953, the comic book industry hit a setback when the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was created in order to investigate the problem of juvenile delinquency.[22] After the publication of Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent the following year that claimed comics sparked illegal behavior among minors, comic book publishers such as EC's William Gaines were subpoenaed to testify in public hearings.[23] As a result, the Comics Code Authority was created by the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers to enact self-censorship by comic book publishers.[24] At this time, EC canceled its crime and horror titles and focused primarily on Mad.[24]

Shift from superheroes

During the late 1940s, the popularity of superhero comics waned. To retain reader interest, comic publishers diversified into other genres, such as war, Westerns, science fiction, romance, crime and horror.[25] Many superhero titles were cancelled or converted to other genres.[citation needed]

In 1946, DC Comics' Superboy, Aquaman and Green Arrow were switched from More Fun Comics into Adventure Comics so More Fun could focus on humor.[26] In 1948 All-American Comics, featuring Green Lantern, Johnny Thunder and Dr. Mid-Nite, was replaced with All-American Western.[citation needed] The following year, Flash Comics and Green Lantern were cancelled.[citation needed] In 1951 All Star Comics, featuring the Justice Society of America, became All-Star Western. The next year Star Spangled Comics, featuring Robin, was retitled Star Spangled War Stories.[citation needed] Sensation Comics, featuring Wonder Woman, was cancelled in 1953.[citation needed] The only superhero comics published continuously through the entire 1950s were Action Comics, Adventure Comics, Batman, Detective Comics, Superboy, Superman, Wonder Woman and World's Finest Comics.[27]

Plastic Man appeared in Quality Comics' Police Comics until 1950, when its focus switched to detective stories; his solo title continued bimonthly until issue 52, cover-dated February 1955. Timely Comics' The Human Torch was canceled with issue #35 (March 1949)[28] and Marvel Mystery Comics, featuring the Human Torch, with issue #93 (Aug. 1949) became the horror comic Marvel Tales.[29] Sub-Mariner Comics was cancelled with issue #42 (June 1949) and Captain America Comics, by then Captain America's Weird Tales, with #75 (Feb. 1950). Harvey Comics' Black Cat was cancelled in 1951 and rebooted as a horror comic later that year—the title would change to Black Cat Mystery, Black Cat Mystic, and eventually Black Cat Western for the final two issues, which included Black Cat stories.[30] Lev Gleason Publications' Daredevil was edged out of his title by the Little Wise Guys in 1950.[31] Fawcett Comics' Whiz Comics, Master Comics and Captain Marvel Adventures were cancelled in 1953, and The Marvel Family was cancelled the following year.[32] The Silver Age of Comic Books is generally recognized as beginning with the debut of the first successful new superhero since the Golden Age, DC Comics' new Flash, in Showcase #4 (Oct. 1956).[33][34][35]

See also

- Silver Age of Comic Books

- Bronze Age of Comic Books

- Modern Age of Comic Books

- List of Golden Age comics publishers

- List of Marvel Comics Golden Age characters

References

- ^ Quattro, Ken (2004). "The New Ages: Rethinking Comic Book History". Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

... according to fanzine historian Bill Schelly, 'The first use of the words "golden age" pertaining to the comics of the 1940s was by Richard A. Lupoff in an article called'"Re-Birth' in Comic Art #1 (April 1960).

- ^ "The Golden Age of Comics". History Detectives: Special Investigations. PBS. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

The precise era of the Golden Age is disputed, though most agree that it was born with the launch of Superman in 1938.

- ^ "Action Comics #1". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 16, 2015.

- ^ Goulart, Ron (2000). Comic Book Culture: An Illustrated History (1st American ed.). Portland, Oregon: Collectors Press. p. 43. ISBN 9781888054385.

- ^ Eury, Michael (2006). The Krypton Companion: A Historical Exploration of Superman Comic Books of 1958-1986. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 116. ISBN 1893905616.

since Superman inspired so many different super-heroes.

- ^ Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature (1st ed.). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 10. ISBN 1578067197.

the various Superman-inspired "costume" comics

- ^ Various (January 19, 2005). The DC Comics Rarities Archives, Vol. 1. New York, New York: DC Comics. ISBN 1401200079.

- ^ Vernon Madison, Nathan (January 3, 2013). Anti-Foreign Imagery in American Pulps and Comic Books, 1920–1960. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0786470952.

- ^ Morse, Ben (July 2006). "Thunderstruck". Wizard (179).

- ^ Madrid, Mike (September 30, 2013). Divas, Dames & Daredevils: Lost Heroines of Golden Age Comics. Minneapolis, MN: Exterminating Angel Press. p. 29.

- ^ "Captain America Comics (1941) #1". Marvel Comics. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ^ Benton, Mike (November 1989). The Comic Book in America: An Illustrated History. Dallas, Texas: Taylor Publishing Company. p. 158. ISBN 0878336591.

- ^ Duncan, Randy; J. Smith, Matthew (January 29, 2013). Icons of the American Comic Book: From Captain America to Wonder Woman, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 193–201. ISBN 978-0313399237.

- ^ "Donald Duck "Lost in the Andes" | The Comics Journal". Tcj.com. January 24, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ Nadel, Dan (Jun 1, 2006). Art Out of Time: Unknown Comics Visionaries, 1900–1969. New York: Abrams Books. p. 8. ISBN 0810958384.

- ^ Telling, Gillian (July 6, 2015). "Mark Waid discusses 'overwhelmingly positive' reaction to Archie Andrews' new look after 75 years of Archie". Entertainment Weekly. Time Inc. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ The War Exchange Conservation Act, 1940, S.C. 1940-41, c. 2

- ^ "Dagwood splits the atom | The Ephemerist". Sparehed.com. 14 May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ^ Zeman, Scott C.; Amundson, Michael A. (2004). Atomic Culture: How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado. p. 11. ISBN 9780870817632.

- ^ Gertler, Nat; Lieber, Steve (6 July 2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel. New York: Alpha Books. p. 178. ISBN 1592572332.

- ^ Farrell, Ken (1 May 2006). Warman's Disney Collectibles Field Guide: Values and Identification. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 327. ISBN 0896893227.

- ^ Binder, Arnold; Geis, Gilbert (1 January 2001). Juvenile Delinquency: Historical, Cultural & Legal Perspectives (Third ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Routledge. p. 220. ISBN 1583605037.

- ^ Kiste Nyberg, Amy (1 February 1998). Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code (Studies in Popular Culture). Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. p. 59. ISBN 087805975X.

- ^ a b Kiste Nyberg, Amy. "Comics Code History: The Seal of Approval". cbldf.org. Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ^ Kovacs, George; Marshall, C. W. (2011). Classics and Comics. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780199734191.

- ^ Daniel, Wallace; Gilbert, Laura (September 20, 2010). DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. New York: DK Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 978-0756667429.

Following More Fun Comics change in focus the previous month, the displaced super-heroes Superboy, Green Arrow, Johnny Quick, Aquaman, and the Shining Knight were welcomed by Adventure Comics.

- ^ Schelly, William (2013). American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1950s. TwoMorrows Publishing. ISBN 9781605490540.

- ^ "The Human Torch". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ "Marvel Mystery Comics". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ^ Schoell, William (June 26, 2014). The Horror Comics: Fiends, Freaks and Fantastic Creatures, 1940–1980s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 82. ISBN 978-0786470273.

- ^ Plowright, Frank (September 22, 2003). The Slings & Arrows Comic Guide. Marietta, Georgia: Top Shelf Productions. p. 159. ISBN 0954458907.

- ^ Conroy, Mike (August 1, 2003). 500 Great Comic Book Action Heroes. Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series. p. 208. ISBN 0764125818.

- ^ Shutt, Craig (2003). Baby Boomer Comics: The Wild, Wacky, Wonderful Comic Books of the 1960s!. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 20. ISBN 087349668X.

The Silver Age started with Showcase #4, the Flash's first appearance.

- ^ Sassiene, Paul (1994). The Comic Book: The One Essential Guide for Comic Book Fans Everywhere. Edison, New Jersey: Chartwell Books, a division of Book Sales. p. 69. ISBN 9781555219994.

DC's Showcase No. 4 was the comic that started the Silver Age

- ^ "DC Flashback: The Flash". Comic Book Resources. July 2, 2007. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

External links

- Comic Book Plus (scans of presumed public domain Golden Age comics)

- Digital Comic Museum (scans of presumed public domain Golden Age comics)

- Don Markstein's Toonopedia

- International Catalogue of Superheroes

- Jess Nevins' Encyclopedia of Golden Age Superheroes

- Villain Paper a Golden Age Comics Subscription Service