Brick

| Brick | |

|---|---|

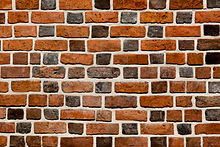

A single brick. |

A brick is a type of construction material used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term brick denotes a unit primarily composed of clay, but is now also used informally to denote units made of other materials or other chemically cured construction blocks. Bricks can be joined using mortar, adhesives or by interlocking.[1][2] Bricks are usually produced at brickworks in numerous classes, types, materials, and sizes which vary with region, and are produced in bulk quantities.[3]

Block is a similar term referring to a rectangular building unit composed of clay or concrete, but is usually larger than a brick. Lightweight bricks (also called lightweight blocks) are made from expanded clay aggregate.

Fired bricks are one of the longest-lasting and strongest building materials, sometimes referred to as artificial stone, and have been used since c. 4000 BC. Air-dried bricks, also known as mudbricks, have a history older than fired bricks, and have an additional ingredient of a mechanical binder such as straw.

Bricks are laid in courses and numerous patterns known as bonds, collectively known as brickwork, and may be laid in various kinds of mortar to hold the bricks together to make a durable structure.

History

Middle East and South Asia

The earliest bricks were dried mudbricks, meaning that they were formed from clay-bearing earth or mud and dried (usually in the sun) until they were strong enough for use. The oldest discovered bricks, originally made from shaped mud and dating before 7500 BC, were found at Tell Aswad, in the upper Tigris region and in southeast Anatolia close to Diyarbakir.[4]

Mudbrick construction was used at Çatalhöyük, from c. 7,400 BC.[5]

Mudbrick structures, dating to c. 7,200 BC have been located in Jericho, Jordan Valley.[6] These structures were made up of the first bricks with dimension 400x150x100 mm.[7]

Between 5000 and 4500 BC, Mesopotamia had discovered fired brick.[7] The standard brick sizes in Mesopotamia followed a general rule: the width of the dried or burned brick would be twice its thickness, and its length would be double its width.[8]

The South Asian inhabitants of Mehrgarh also constructed air-dried mudbrick structures between 7000 and 3300 BC[9] and later the ancient Indus Valley cities of Mohenjo-daro, Harappa,[10] and Mehrgarh.[11] Ceramic, or fired brick was used as early as 3000 BC in early Indus Valley cities like Kalibangan.[12]

In the middle of the third millennium BC, there was a rise in monumental baked brick architecture in Indus cities. Examples included the Great Bath at Mohenjo-daro, the fire altars of Kaalibangan, and the granary of Harappa. There was a uniformity to the brick sizes throughout the Indus Valley region, conforming to the 1:2:4, thickness, width, and length ratio. As the Indus civilization began its decline at the start of the second millennium BC, Harappans migrated east, spreading their knowledge of brickmaking technology. This led to the rise of cities like Pataliputra, Kausambi, and Ujjain, where there was an enormous demand for kiln-made bricks.[13]

By 604 BC, bricks were the construction materials for architectural wonders such as the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, where glazed fired bricks were put into practice.[7]

China

The earliest fired bricks appeared in Neolithic China around 4400 BC at Chengtoushan, a walled settlement of the Daxi culture.[14] These bricks were made of red clay, fired on all sides to above 600 °C, and used as flooring for houses. By the Qujialing period (3300 BC), fired bricks were being used to pave roads and as building foundations at Chengtoushan.[15]

According to Lukas Nickel, the use of ceramic pieces for protecting and decorating floors and walls dates back at various cultural sites to 3000-2000 BC and perhaps even before, but these elements should be rather qualified as tiles. For the longest time builders relied on wood, mud and rammed earth, while fired brick and mudbrick played no structural role in architecture. Proper brick construction, for erecting walls and vaults, finally emerges in the third century BC, when baked bricks of regular shape began to be employed for vaulting underground tombs. Hollow brick tomb chambers rose in popularity as builders were forced to adapt due to a lack of readily available wood or stone.[16] The oldest extant brick building above ground is possibly Songyue Pagoda, dated to 523 AD.

By the end of the third century BC in China, both hollow and small bricks were available for use in building walls and ceilings. Fired bricks were first mass-produced during the construction of the tomb of China's first Emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi. The floors of the three pits of the terracotta army were paved with an estimated 230,000 bricks, with the majority measuring 28x14x7 cm, following a 4:2:1 ratio. The use of fired bricks in Chinese city walls first appeared in the Eastern Han dynasty (25 AD-220 AD).[17] Up until the Middle Ages, buildings in Central Asia were typically built with unbaked bricks. It was only starting in the ninth century CE when buildings were entirely constructed using fired bricks.[16]

The carpenter's manual Yingzao Fashi, published in 1103 at the time of the Song dynasty described the brick making process and glazing techniques then in use. Using the 17th-century encyclopaedic text Tiangong Kaiwu, historian Timothy Brook outlined the brick production process of Ming dynasty China:

...the kilnmaster had to make sure that the temperature inside the kiln stayed at a level that caused the clay to shimmer with the colour of molten gold or silver. He also had to know when to quench the kiln with water so as to produce the surface glaze. To anonymous labourers fell the less skilled stages of brick production: mixing clay and water, driving oxen over the mixture to trample it into a thick paste, scooping the paste into standardised wooden frames (to produce a brick roughly 42 cm long, 20 cm wide, and 10 cm thick), smoothing the surfaces with a wire-strung bow, removing them from the frames, printing the fronts and backs with stamps that indicated where the bricks came from and who made them, loading the kilns with fuel (likelier wood than coal), stacking the bricks in the kiln, removing them to cool while the kilns were still hot, and bundling them into pallets for transportation. It was hot, filthy work.

Europe

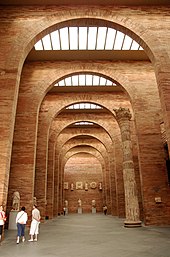

Early civilisations around the Mediterranean, including the Ancient Greeks and Romans, adopted the use of fired bricks. By the early first century CE, standardised fired bricks were being heavily produced in Rome.[18] The Roman legions operated mobile kilns,[19] and built large brick structures throughout the Roman Empire, stamping the bricks with the seal of the legion.[20] The Romans used brick for walls, arches, forts, aqueducts, etc. Notable mentions of Roman brick structures are the Herculaneum gate of Pompeii and the baths of Caracalla.[21]

During the Early Middle Ages the use of bricks in construction became popular in Northern Europe, after being introduced there from Northwestern Italy. An independent style of brick architecture, known as brick Gothic (similar to Gothic architecture) flourished in places that lacked indigenous sources of rocks. Examples of this architectural style can be found in modern-day Denmark, Germany, Poland, and Kaliningrad (former East Prussia).[22]

This style evolved into the Brick Renaissance as the stylistic changes associated with the Italian Renaissance spread to northern Europe, leading to the adoption of Renaissance elements into brick building. Identifiable attributes included a low-pitched hipped or flat roof, symmetrical facade, round arch entrances and windows, columns and pilasters, and more.[23]

A clear distinction between the two styles only developed at the transition to Baroque architecture. In Lübeck, for example, Brick Renaissance is clearly recognisable in buildings equipped with terracotta reliefs by the artist Statius von Düren, who was also active at Schwerin (Schwerin Castle) and Wismar (Fürstenhof).[24]

Long-distance bulk transport of bricks and other construction equipment remained prohibitively expensive until the development of modern transportation infrastructure, with the construction of canal, roads, and railways.[25]

Industrial era

Production of bricks increased massively with the onset of the Industrial Revolution and the rise in factory building in England. For reasons of speed and economy, bricks were increasingly preferred as building material to stone, even in areas where the stone was readily available. It was at this time in London that bright red brick was chosen for construction to make the buildings more visible in the heavy fog and to help prevent traffic accidents.[27]

The transition from the traditional method of production known as hand-moulding to a mechanised form of mass-production slowly took place during the first half of the nineteenth century. The first brick-making machine was patented by Richard A. Ver Valen of Haverstraw, New York, in 1852.[28] The Bradley & Craven Ltd 'Stiff-Plastic Brickmaking Machine' was patented in 1853. Bradley & Craven went on to be a dominant manufacturer of brickmaking machinery.[29] Henry Clayton, employed at the Atlas Works in Middlesex, England, in 1855, patented a brick-making machine that was capable of producing up to 25,000 bricks daily with minimal supervision.[30] His mechanical apparatus soon achieved widespread attention after it was adopted for use by the South Eastern Railway Company for brick-making at their factory near Folkestone.[31]

At the end of the 19th century, the Hudson River region of New York State would become the world's largest brick manufacturing region, with 130 brickyards lining the shores of the Hudson River from Mechanicsville to Haverstraw and employing 8,000 people. At its peak, about 1 billion bricks were produced a year, with many being sent to New York City for use in its construction industry.[32]

The demand for high office building construction at the turn of the 20th century led to a much greater use of cast and wrought iron, and later, steel and concrete. The use of brick for skyscraper construction severely limited the size of the building – the Monadnock Building, built in 1896 in Chicago, required exceptionally thick walls to maintain the structural integrity of its 17 storeys.[33]

Following pioneering work in the 1950s at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology and the Building Research Establishment in Watford, UK, the use of improved masonry for the construction of tall structures up to 18 storeys high was made viable. However, the use of brick has largely remained restricted to small to medium-sized buildings, as steel and concrete remain superior materials for high-rise construction.[34]

Methods of manufacture

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

Four basic types of brick are un-fired, fired, chemically set bricks, and compressed earth blocks. Each type is manufactured differently for various purposes.

Mudbrick

Unfired bricks, also known as mudbrick, are made from a mixture of silt, clay, sand and other earth materials like gravel and stone, combined with tempers and binding agents such as chopped straw, grasses, tree bark, or dung.[35][36] Since these bricks are made up of natural materials and only require heat from the Sun to bake, mudbricks have a relatively low embodied energy and carbon footprint.

The ingredients are first harvested and added together, with clay content ranging from 30% to 70%.[37] The mixture is broken up with hoes or adzes, and stirred with water to form a homogenous blend. Next, the tempers and binding agents are added in a ratio, roughly one part straw to five parts earth to reduce weight and reinforce the brick by helping reduce shrinkage.[38] However, additional clay could be added to reduce the need for straw, which would prevent the likelihood of insects deteriorating the organic material of the bricks, subsequently weakening the structure. These ingredients are thoroughly mixed together by hand or by treading and are then left to ferment for about a day.[35]

The mix is then kneaded with water and molded into rectangular prisms of a desired size. Bricks are lined up and left to dry in the sun for three days on both sides. After the six days, the bricks continue drying until required for use. Typically, longer drying times are preferred, but the average is eight to nine days spanning from initial stages to its application in structures. Unfired bricks could be made in the spring months and left to dry over the summer for use in the autumn. Mudbricks are commonly employed in arid environments to allow for adequate air drying.[35]

Fired brick

Fired bricks are baked in a kiln which makes them durable. Modern, fired, clay bricks are formed in one of three processes – soft mud, dry press, or extruded. Depending on the country, either the extruded or soft mud method is the most common, since they are the most economical.

Clay and shale are the raw ingredients in the recipe for a fired brick. They are the product of thousands of years of decomposition and erosion of rocks, such as pegmatite and granite, leading to a material that has properties of being highly chemically stable and inert. Within the clays and shales are the materials of aluminosilicate (pure clay), free silica (quartz), and decomposed rock.[39]

One proposed optimal mix is:[40]

- Silica (sand) – 50% to 60% by weight

- Alumina (clay) – 20% to 30% by weight

- Lime – 2 to 5% by weight

- Iron oxide – ≤ 7% by weight

- Magnesia – less than 1% by weight

Shaping methods

Three main methods are used for shaping the raw materials into bricks to be fired:

- Moulded bricks – These bricks start with raw clay, preferably in a mix with 25–30% sand to reduce shrinkage. The clay is first ground and mixed with water to the desired consistency. The clay is then pressed into steel moulds with a hydraulic press. The shaped clay is then fired at 900–1,000 °C (1,650–1,830 °F) to achieve strength.

- Dry-pressed bricks – The dry-press method is similar to the soft-mud moulded method, but starts with a much thicker clay mix, so it forms more accurate, sharper-edged bricks. The greater force in pressing and the longer firing time make this method more expensive.

- Extruded bricks – For extruded bricks the clay is mixed with 10–15% water (stiff extrusion) or 20–25% water (soft extrusion) in a pugmill. This mixture is forced through a die to create a long cable of material of the desired width and depth. This mass is then cut into bricks of the desired length by a wall of wires. Most structural bricks are made by this method as it produces hard, dense bricks, and suitable dies can produce perforations as well. The introduction of such holes reduces the volume of clay needed, and hence the cost. Hollow bricks are lighter and easier to handle, and have different thermal properties from solid bricks. The cut bricks are hardened by drying for 20 to 40 hours at 50 to 150 °C (120 to 300 °F) before being fired. The heat for drying is often waste heat from the kiln.

Kilns

In many modern brickworks, bricks are usually fired in a continuously fired tunnel kiln, in which the bricks are fired as they move slowly through the kiln on conveyors, rails, or kiln cars, which achieves a more consistent brick product. The bricks often have lime, ash, and organic matter added, which accelerates the burning process.

The other major kiln type is the Bull's Trench Kiln (BTK), based on a design developed by British engineer W. Bull in the late 19th century.

An oval or circular trench is dug, 6–9 metres (20–30 ft) wide, 2–2.5 metres (6 ft 7 in – 8 ft 2 in) deep, and 100–150 metres (330–490 ft) in circumference. A tall exhaust chimney is constructed in the centre. Half or more of the trench is filled with "green" (unfired) bricks which are stacked in an open lattice pattern to allow airflow. The lattice is capped with a roofing layer of finished brick.

In operation, new green bricks, along with roofing bricks, are stacked at one end of the brick pile. Historically, a stack of unfired bricks covered for protection from the weather was called a "hack".[41] Cooled finished bricks are removed from the other end for transport to their destinations. In the middle, the brick workers create a firing zone by dropping fuel (coal, wood, oil, debris, etc.) through access holes in the roof above the trench. The constant source of fuel maybe grown on the woodlots.[3]: 6

The advantage of the BTK design is a much greater energy efficiency compared with clamp or scove kilns. Sheet metal or boards are used to route the airflow through the brick lattice so that fresh air flows first through the recently burned bricks, heating the air, then through the active burning zone. The air continues through the green brick zone (pre-heating and drying the bricks), and finally out the chimney, where the rising gases create suction that pulls air through the system. The reuse of heated air yields savings in fuel cost.

As with the rail process, the BTK process is continuous. A half-dozen labourers working around the clock can fire approximately 15,000–25,000 bricks a day. Unlike the rail process, in the BTK process the bricks do not move. Instead, the locations at which the bricks are loaded, fired, and unloaded gradually rotate through the trench.[42]

Influences on colour

The colour of fired clay bricks is influenced by the chemical and mineral content of the raw materials, the firing temperature, and the atmosphere in the kiln. For example, pink bricks are the result of a high iron content, white or yellow bricks have a higher lime content.[43] Most bricks burn to various red hues; as the temperature is increased the colour moves through dark red, purple, and then to brown or grey at around 1,300 °C (2,370 °F). The names of bricks may reflect their origin and colour, such as London stock brick and Cambridgeshire White. Brick tinting may be performed to change the colour of bricks to blend-in areas of brickwork with the surrounding masonry.

An impervious and ornamental surface may be laid on brick either by salt glazing, in which salt is added during the burning process, or by the use of a slip, which is a glaze material into which the bricks are dipped. Subsequent reheating in the kiln fuses the slip into a glazed surface integral with the brick base.

Chemically set bricks

Chemically set bricks are not fired but may have the curing process accelerated by the application of heat and pressure in an autoclave.

Calcium-silicate bricks

Calcium-silicate bricks are also called sandlime or flintlime bricks, depending on their ingredients. Rather than being made with clay they are made with lime binding the silicate material. The raw materials for calcium-silicate bricks include lime mixed in a proportion of about 1 to 10 with sand, quartz, crushed flint, or crushed siliceous rock together with mineral colourants. The materials are mixed and left until the lime is completely hydrated; the mixture is then pressed into moulds and cured in an autoclave for three to fourteen hours to speed the chemical hardening.[44] The finished bricks are very accurate and uniform, although the sharp arrises need careful handling to avoid damage to brick and bricklayer. The bricks can be made in a variety of colours; white, black, buff, and grey-blues are common, and pastel shades can be achieved. This type of brick is common in Sweden as well as Russia and other post-Soviet countries, especially in houses built or renovated in the 1970s. A version known as fly ash bricks, manufactured using fly ash, lime, and gypsum (known as the FaL-G process) are common in South Asia. Calcium-silicate bricks are also manufactured in Canada and the United States, and meet the criteria set forth in ASTM C73 – 10 Standard Specification for Calcium Silicate Brick (Sand-Lime Brick).

Concrete bricks

Bricks formed from concrete are usually termed as blocks or concrete masonry unit, and are typically pale grey. They are made from a dry, small aggregate concrete which is formed in steel moulds by vibration and compaction in either an "egglayer" or static machine. The finished blocks are cured, rather than fired, using low-pressure steam. Concrete bricks and blocks are manufactured in a wide range of shapes, sizes and face treatments – a number of which simulate the appearance of clay bricks.

Concrete bricks are available in many colours and as an engineering brick made with sulfate-resisting Portland cement or equivalent. When made with adequate amount of cement they are suitable for harsh environments such as wet conditions and retaining walls. They are made to standards BS 6073, EN 771-3 or ASTM C55. Concrete bricks contract or shrink so they need movement joints every 5 to 6 metres, but are similar to other bricks of similar density in thermal and sound resistance and fire resistance.[44]

Compressed earth blocks

Compressed earth blocks are made mostly from slightly moistened local soils compressed with a mechanical hydraulic press or manual lever press. A small amount of a cement binder may be added, resulting in a stabilised compressed earth block.

Types

There are thousands of types of bricks that are named for their use, size, forming method, origin, quality, texture, and/or materials.

Categorized by manufacture method:

- Extruded – made by being forced through an opening in a steel die, with a very consistent size and shape.

- Wire-cut – cut to size after extrusion with a tensioned wire which may leave drag marks

- Moulded – shaped in moulds rather than being extruded

- Machine-moulded – clay is forced into moulds using pressure

- Handmade – clay is forced into moulds by a person

- Dry-pressed – similar to soft mud method, but starts with a much thicker clay mix and is compressed with great force.

Categorized by use:

- Common or building – A brick not intended to be visible, used for internal structure

- Face – A brick used on exterior surfaces to present a clean appearance

- Hollow – not solid, the holes are less than 25% of the brick volume

- Perforated – holes greater than 25% of the brick volume

- Keyed – indentations in at least one face and end to be used with rendering and plastering

- Paving – brick intended to be in ground contact as a walkway or roadway

- Thin – brick with normal height and length but thin width to be used as a veneer

Specialized use bricks:

- Chemically resistant – bricks made with resistance to chemical reactions

- Acid brick – acid resistant bricks

- Engineering – a type of hard, dense, brick used where strength, low water porosity or acid (flue gas) resistance are needed. Further classified as type A and type B based on their compressive strength

- Accrington – a type of engineering brick from England

- Fire or refractory – highly heat-resistant bricks

- Clinker – a vitrified brick

- Ceramic glazed – fire bricks with a decorative glazing

Bricks named for place of origin:

- Chicago common brick - a soft brick made near Chicago, Illinois with a range of colors, like buff yellow, salmon pink, or deep red

- Cream City brick – a light yellow brick made in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

- Dutch brick – a hard light coloured brick originally from the Netherlands

- Fareham red brick – a type of construction brick

- London stock brick – type of handmade brick which was used for the majority of building work in London and South East England until the growth in the use of machine-made bricks

- Nanak Shahi bricks – a type of decorative brick in India

- Roman brick – a long, flat brick typically used by the Romans

- Staffordshire blue brick – a type of construction brick from England

Optimal dimensions, characteristics, and strength

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

For efficient handling and laying, bricks must be small enough and light enough to be picked up by the bricklayer using one hand (leaving the other hand free for the trowel). Bricks are usually laid flat, and as a result, the effective limit on the width of a brick is set by the distance which can conveniently be spanned between the thumb and fingers of one hand, normally about 100 mm (4 in). In most cases, the length of a brick is twice its width plus the width of a mortar joint, about 200 mm (8 in) or slightly more. This allows bricks to be laid bonded in a structure which increases stability and strength (for an example, see the illustration of bricks laid in English bond, at the head of this article). The wall is built using alternating courses of stretchers, bricks laid longways, and headers, bricks laid crossways. The headers tie the wall together over its width. In fact, this wall is built in a variation of English bond called English cross bond where the successive layers of stretchers are displaced horizontally from each other by half a brick length. In true English bond, the perpendicular lines of the stretcher courses are in line with each other.

A bigger brick makes for a thicker (and thus more insulating) wall. Historically, this meant that bigger bricks were necessary in colder climates (see for instance the slightly larger size of the Russian brick in table below), while a smaller brick was adequate, and more economical, in warmer regions. A notable illustration of this correlation is the Green Gate in Gdansk; built in 1571 of imported Dutch brick, too small for the colder climate of Gdansk, it was notorious for being a chilly and drafty residence. Nowadays this is no longer an issue, as modern walls typically incorporate specialised insulation materials.

The correct brick for a job can be selected from a choice of colour, surface texture, density, weight, absorption, and pore structure, thermal characteristics, thermal and moisture movement, and fire resistance.

| Standard | Metric (mm) | Imperial (inches) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| 230 × 110 × 76 | 9.1 × 4.3 × 3.0 | 3:1.4:1 | |

| 240 × 155 × 53 | 9.4 × 6.1 × 2.1 | 4.5:2.9:1 | |

| 228 × 108 × 54 | 9.0 × 4.3 × 2.1 | 4.3:2:1 | |

| 240 × 115 × 71 | 9.4 × 4.5 × 2.8 | 3.4:1.6:1 | |

| 228 × 107 × 69 | 9.0 × 4.2 × 2.7 | 3.3:1.6:1 | |

| 210 × 100 × 60 | 8.3 × 3.9 × 2.4 | 3.5:1.6:1 | |

| 240 × 115 × 63 | 9.4 × 4.5 × 2.5 | 3.8:1.8:1 | |

| 250 × 120 × 65 | 9.8 × 4.7 × 2.6 | 3.8:1.8:1 | |

| 222 × 106 × 73 | 8.7 × 4.2 × 2.9 | 3:1.4:1 | |

| 250 × 120 × 62 | 9.8 × 4.7 × 2.4 | 4.1:2:1 | |

| 215 × 102.5 × 65 | 8.5 × 4.0 × 2.6 | 3.3:1.5:1 | |

| 194 × 92 × 57 | 7.6 × 3.6 × 2.2 | 3.5:1.6:1 |

In England, the length and width of the common brick remained fairly constant from 1625 when the size was regulated by statute at 9 x 4+1⁄2 x 3 inches[45] (but see brick tax), but the depth has varied from about two inches (51 mm) or smaller in earlier times to about 2+1⁄2 inches (64 mm) more recently. In the United Kingdom, the usual size of a modern brick (from 1965)[46] is 215 mm × 102.5 mm × 65 mm (8+1⁄2 in × 4 in × 2+1⁄2 in), which, with a nominal 10 millimetres (3⁄8 in) mortar joint, forms a unit size of 225 by 112.5 by 75 millimetres (9 in × 4+1⁄2 in × 3 in), for a ratio of 6:3:2.

In the United States, modern standard bricks are specified for various uses;[47] The most commonly used is the modular brick has the actual dimensions of 7+5⁄8 × 3+5⁄8 × 2+1⁄4 inches (194 × 92 × 57 mm). With the standard 3⁄8 inch mortar joint, this gives the nominal dimensions of 8 x 4 x 2+2⁄3 inches which eases the calculation of the number of bricks in a given wall.[48] The 2:1 ratio of modular bricks means that when they turn corners, a 1/2 running bond is formed without needing to cut the brick down or fill the gap with a cut brick; and the height of modular bricks means that a soldier course matches the height of three modular running courses, or one standard CMU course.

Some brickmakers create innovative sizes and shapes for bricks used for plastering (and therefore not visible on the inside of the building) where their inherent mechanical properties are more important than their visual ones.[49] These bricks are usually slightly larger, but not as large as blocks and offer the following advantages:

- A slightly larger brick requires less mortar and handling (fewer bricks), which reduces cost

- Their ribbed exterior aids plastering

- More complex interior cavities allow improved insulation, while maintaining strength.

Blocks have a much greater range of sizes. Standard co-ordinating sizes in length and height (in mm) include 400×200, 450×150, 450×200, 450×225, 450×300, 600×150, 600×200, and 600×225; depths (work size, mm) include 60, 75, 90, 100, 115, 140, 150, 190, 200, 225, and 250.[43] They are usable across this range as they are lighter than clay bricks. The density of solid clay bricks is around 2000 kg/m3: this is reduced by frogging, hollow bricks, and so on, but aerated autoclaved concrete, even as a solid brick, can have densities in the range of 450–850 kg/m3.

Bricks may also be classified as solid (less than 25% perforations by volume, although the brick may be "frogged," having indentations on one of the longer faces), perforated (containing a pattern of small holes through the brick, removing no more than 25% of the volume), cellular (containing a pattern of holes removing more than 20% of the volume, but closed on one face), or hollow (containing a pattern of large holes removing more than 25% of the brick's volume). Blocks may be solid, cellular or hollow.

The term "frog" can refer to the indentation or the implement used to make it. Modern brickmakers usually use plastic frogs but in the past they were made of wood.

The compressive strength of bricks produced in the United States ranges from about 7 to 103 MPa (1,000 to 15,000 lbf/in2), varying according to the use to which the brick are to be put. In England clay bricks can have strengths of up to 100 MPa, although a common house brick is likely to show a range of 20–40 MPa.

Uses

Bricks are a versatile building material, able to participate in a wide variety of applications, including:[39]

- Structural walls, exterior and interior walls

- Bearing and non-bearing sound proof partitions

- The fireproofing of structural-steel members in the form of firewalls, party walls, enclosures and fire towers

- Foundations for stucco

- Chimneys and fireplaces

- Porches and terraces

- Outdoor steps, brick walks and paved floors

- Swimming pools

In the United States, bricks have been used for both buildings and pavement. Examples of brick use in buildings can be seen in colonial era buildings and other notable structures around the country. Bricks have been used in paving roads and sidewalks especially during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The introduction of asphalt and concrete reduced the use of brick for paving, but they are still sometimes installed as a method of traffic calming or as a decorative surface in pedestrian precincts. For example, in the early 1900s, most of the streets in the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan, were paved with bricks. Today, there are only about 20 blocks of brick-paved streets remaining (totalling less than 0.5 percent of all the streets in the city limits).[50] Much like in Grand Rapids, municipalities across the United States began replacing brick streets with inexpensive asphalt concrete by the mid-20th century.[51]

In Northwest Europe, bricks have been used in construction for centuries. Until recently, almost all houses were built almost entirely from bricks. Although many houses are now built using a mixture of concrete blocks and other materials, many houses are skinned with a layer of bricks on the outside for aesthetic appeal.

Bricks in the metallurgy and glass industries are often used for lining furnaces, in particular refractory bricks such as silica, magnesia, chamotte and neutral (chromomagnesite) refractory bricks. This type of brick must have good thermal shock resistance, refractoriness under load, high melting point, and satisfactory porosity. There is a large refractory brick industry, especially in the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Engineering bricks are used where strength, low water porosity or acid (flue gas) resistance are needed.

In the UK a red brick university is one founded in the late 19th or early 20th century. The term is used to refer to such institutions collectively to distinguish them from the older Oxbridge institutions, and refers to the use of bricks, as opposed to stone, in their buildings.

Colombian architect Rogelio Salmona was noted for his extensive use of red bricks in his buildings and for using natural shapes like spirals, radial geometry and curves in his designs.[52]

Limitations

Starting in the 20th century, the use of brickwork declined in some areas due to concerns about earthquakes. Earthquakes such as the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 and the 1933 Long Beach earthquake revealed the weaknesses of unreinforced brick masonry in earthquake-prone areas. During seismic events, the mortar cracks and crumbles, so that the bricks are no longer held together. Brick masonry with steel reinforcement, which helps hold the masonry together during earthquakes, has been used to replace unreinforced bricks in many buildings. Retrofitting older unreinforced masonry structures has been mandated in many jurisdictions. However, similar to steel corrosion in reinforced concrete, rebar rusting will compromise the structural integrity of reinforced brick and ultimately limit the expected lifetime, so there is a trade-off between earthquake safety and longevity to a certain extent.

Accessibility

The United States Access Board does not specify which materials a sidewalk must be made of in order to be ADA compliant, but states that sidewalks must not have surface variances of greater than one inch.[53] Due to the accessibility challenges of bricks, the Federal Highway Administration recommends against the use of bricks as well as cobblestones in its accessibility guide for sidewalks and crosswalks. The Brick Industry Association maintains standards for making brick more accessible for disabled people, with proper and regular maintenance being necessary to keep brick accessible.[54]

Some US jurisdictions, such as San Francisco, have taken steps to remove brick sidewalks from certain areas such as Market Street in order to improve accessibility.[54]

Gallery

-

Chile house in Hamburg, Germany

-

A block of Bricks manufactured in Nepal to build Ancient Stupa

-

Roman opus reticulatum on Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli, Italy (2nd century)

-

Frauenkirche, Munich, Germany, erected 1468–1488, looking up at the towers

-

Eastern gable of church of St. James in Toruń (14th century)

-

Decorative pattern made of strongly fired bricks in Radzyń Castle (14th century)

-

Brick sculpting on Thornbury Castle, Thornbury, near Bristol, England. The chimneys were erected in 1514

-

A typical brick house in the Netherlands.

-

A 19th-century brick church in Loppi, Finland

-

A typical Dutch farmhouse near Wageningen, Netherlands

-

Decorative bricks in St Michael and All Angels Church, Blantyre, Malawi

-

Virgilio Barco Public Library, Bogotá, Colombia

-

FES Building, Cali, Colombia

-

A brick kiln, Tamil Nadu, India

-

Brick sidewalk paving in Portland, Oregon, U.S.

-

Brick sidewalk in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

-

Porotherm style clay block brick

-

Moulding bricks, Poland

-

Brick made as a byproduct of ironstone mining Normanby – UK

-

Fired, clay bricks in Hainan, China

-

The largest brick warehouse in the world, Stanley Dock Tobacco Warehouse, Liverpool, UK

-

Medieval heir to the Roman brick in the Toulouse region, the "Foraine" brick has kept the same large and flat format.

-

The Albi Cathedral (France) was built using "Foraine" bricks.

See also

- Autoclaved aerated concrete – Lightweight, precast building material

- Banna'i – Use of glazed tiles alternating with plain brick for decorative purposes

- Ceramic building material – Archaeological term for baked clay building material

- Glossary of British bricklaying – List of bricklaying terms and their meanings

- Opus africanum – Form of ashlar masonry used in Carthaginian and ancient Roman architecture

- Opus latericium – Ancient Roman brickwork construction

- Opus mixtum – Combination of Roman construction techniques

- Opus spicatum – Masonry pattern used in Roman and medieval times

- Opus vittatum – Roman construction technique using horizontal courses of tuff blocks alternated with bricks

- Polychrome brickwork – Use of bricks of different colours for decoration

- Stockade Building System – Building block system using compressed wood shavings

- Surfaced block – Concrete masonry unit with a durable, slick surface

- Wienerberger – Manufacturer of bricks, pavers and pipes

References

- ^ "Interlocking bricks & Compressed stablized earth bricks - CSEB". Buildup Nepal.

- ^ "Bricks that interlock".

- ^ a b W., Beamish, A. Donovan (1990). Village-level brickmaking. Vieweg. ISBN 3-528-02051-2. OCLC 472930436.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ (in French) IFP Orient – Tell Aswad Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Wikis.ifporient.org. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Neolithic Site of Çatalhöyük". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Mud-brick Village Survived 7,200 Years in the Jordan Valley". Haaretz. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Fiala, Jan; Mikolas, Milan; Fiala Junior, Jan; Krejsova, Katerina (2019). "History and Evolution of Full Bricks of Other European Countries". IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 603 (3): 032097. Bibcode:2019MS&E..603c2097F. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/603/3/032097. S2CID 203996304.

- ^ Hasson Hnaihen, Kadim (18 December 2019). "The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia". Athens Journal of History. 6 (1): 73–96. doi:10.30958/ajhis.6-1-4. ISSN 2407-9677. S2CID 214024042.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (1996)

- ^ History of brickmaking, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (2005), "Uncovering the keys to the Lost Indus Cities", Scientific American, 15 (1): 24–33, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0105-24sp, PMID 12840948

- ^ Khan, Aurangzeb; Lemmen, Carsten (2013), Bricks and urbanism in the Indus Valley rise and decline, arXiv:1303.1426, Bibcode:2013arXiv1303.1426K

- ^ Gupta, Sunil (May–June 1998). "History of Brick in India" (PDF). ARCHITECTURE+DESIGN. pp. 74–78. Retrieved 4 December 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Yoshinori Yasuda (2012). Water Civilization: From Yangtze to Khmer Civilizations. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 30–31. ISBN 9784431541103.

- ^ Yoshinori Yasuda (2012). Water Civilization: From Yangtze to Khmer Civilizations. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 33–35. ISBN 9784431541103.

- ^ a b Lukas Nickel: Bricks in Ancient China and the Question of Early Cross-Asian Interaction, Arts Asiatiques, Vol. 70 (2015), pp. 49-62 (50f.)

- ^ Xue, Q.; Jin, X.; Cheng, Y.; Yang, X.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Y. (2019). "The historical process of the masonry city walls construction in China during 1st to 17th centuries AD". PLOS ONE. 14 (3): e0214119. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1414119X. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0214119. PMC 6430406. PMID 30901369.

- ^ Östborn, Per; Gerding, Henrik (1 March 2015). "The Diffusion of Fired Bricks in Hellenistic Europe: A Similarity Network Analysis". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 22 (1): 306–344. doi:10.1007/s10816-014-9229-4. ISSN 1573-7764. S2CID 254606236.

- ^ Ash, Ahmed (20 November 2014). Materials science in construction : an introduction. Sturges, John. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 9781135138417. OCLC 896794727.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Roman Brick Stamps: Auxiliary and Legionary Bricks". www.romancoins.info. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ 2fm.pl; BrickArchitecture.com. "The History of Bricks and Brickmaking". brickarchitecture.com. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Discover Brick Gothic architecture on the European route | DW | 01.06.2010". DW.COM. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ "Italian Renaissance Revival Style 1890 - 1930 | PHMC > Pennsylvania Architectural Field Guide". www.phmc.state.pa.us. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Schloss Schwerin | Welterbe Schwerin". www.welterbe-schwerin.de (in German). Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ "General information on the history of the brick | Scotland's Brick and Tile Manufacturing Industry". www.scottishbrickhistory.co.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2024.

- ^ Wiskemann, Barbara (2005). "Prefabrication". In Deplazes, Andrea (ed.). Constructing Architecture: Materials, Processes, Structures (PDF). Basel, Boston & Berlin: Birkhäuser – Publishers for Architecture. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-7643-7313-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ Peter Ackroyd (2001). London the Biography. Random House. p. 435. ISBN 978-0-09-942258-7.

- ^ "US Patent 9082". Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ The First Hundred Years: the Early History of Bradley & Craven, Limited, Wakefield, England by Bradley & Craven Ltd (1963)

- ^ "Henry Clayton". Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ The Mechanics Magazine and Journal of Engineering, Agricultural Machinery, Manufactures and Shipbuilding. 1859. p. 361.

- ^ Falkenstein, Michelle (28 June 2022). "Brick collectors of the Hudson Valley". www.timesunion.com. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Monadnock Building: The Last Brick Skyscraper". www.amusingplanet.com. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "The History of Bricks". De Hoop:Steenwerve Brickfields.

- ^ a b c Emery, Virginia L. (27 August 2009). "Mud-Brick". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1).

- ^ Homsher, Robert S. (November 2012). "Mud Bricks and the Process of Construction in the Middle Bronze Age Southern Levant". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 368: 1–27. doi:10.5615/bullamerschoorie.368.0001. ISSN 0003-097X. S2CID 164826274.

- ^ Downton, Paul; Clarke, Dick (2020). "Mud brick". YourHome. Retrieved 11 December 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tintner, Johannes; Roth, Kimberly; Ottner, Franz; Syrová-Anýžová, Zuzana; Žabičková, Ivana; Wriessnig, Karin; Meingast, Roland; Feiglstorfer, Hubert (20 March 2020). "Straw in Clay Bricks and Plasters—Can We Use Its Molecular Decay for Dating Purposes?". Molecules. 25 (6): 1419. doi:10.3390/molecules25061419. ISSN 1420-3049. PMC 7144354. PMID 32244982.

- ^ a b Stoddard, Ralph Perkins; Carver, William (1946). Brick structures, how to build them ; practical reference data on materials, design, and construction methods employed in brick construction ... New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Punmia, B.C.; Jain, Ashok Kumar (2003), Basic Civil Engineering, Firewall Media, p. 33, ISBN 978-81-7008-403-7

- ^ Connolly, Andrew. Life in the Victorian Brickyards of Flintshire and Denbigshire, p34. 2003, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch.

- ^ Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency, Brick Kiln Units (PDF file) Archived 16 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Almssad, Asaad; Almusaed, Amjad; Homod, Raad Z. (January 2022). "Masonry in the Context of Sustainable Buildings: A Review of the Brick Role in Architecture". Sustainability. 14 (22): 14734. doi:10.3390/su142214734. ISSN 2071-1050.

- ^ a b McArthur, Hugh, and Duncan Spalding. Engineering materials science: properties, uses, degradation and remediation. Chichester, U.K.: Horwood Pub., 2004. 194. Print.

- ^ Burton, Joseph & William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 518.

- ^ "Brick sizes, variations and standardisation". Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ [1] Archived 29 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Brick Industry Association. Technical Note 9A, Specifications for and Classification of Brick. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ [2] Archived 11 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine bia.org. Technical Note 10, Dimensioning and Estimating Brick Masonry (pdf file) Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Crammix Maxilite. crammix.co.za

- ^ Michigan | Success Stories | Preserve America | Office of the Secretary of Transportation | U.S. Department of Transportation.

- ^ Schwartz, Emma (31 July 2003). "Bricks come back to city streets". USA Today. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Romero, Simon (6 October 2007). "Rogelio Salmona, Colombian Architect Who Transformed Cities, Is Dead at 78". The New York Times.

- ^ "ADA Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG)". United States Access Board. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ a b "San Francisco Will Say So Long to Brick Sidewalk". Next City. Retrieved 11 August 2024.

- ^ Alejandro Porcel Arraut (16 October 2018). "Desarrollo inmobiliario en Xoco: relato de ciudades enfrentadas". Nexos (magazine) (in Spanish).

Further reading

- Aragus, Philippe (2003), Brique et architecture dans l'Espagne médiévale, Bibliothèque de la Casa de Velazquez, 2 (in French), Madrid

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Campbell, James W.; Pryce, Will, photographer (2003), Brick: a World History, London & New York: Thames & Hudson

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Coomands, Thomas; VanRoyen, Harry, eds. (2008), "Novii Monasterii, 7", Medieval Brick Architecture in Flanders and Northern Europe, Koksijde: Ten Duinen

- Das, Saikia Mimi; Das, Bhargab Mohan; Das, Madan Mohan (2010), Elements of Civil Engineering, New Delhi: PHI Learning Private Limited, ISBN 978-81-203-4097-8

- Kornmann, M.; CTTB (2007), Clay Bricks and Roof Tiles, Manufacturing and Properties, Paris: Lasim, ISBN 978-2-9517765-6-2

- Plumbridge, Andrew; Meulenkamp, Wim (2000), Brickwork. Architecture and Design, London: Seven Dials, ISBN 1-84188-039-6

- Dobson, E. A. (1850), Rudimentary Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks and Tiles, London: John Weale

- Hudson, Kenneth (1972) Building Materials; chap. 3: Bricks and tiles. London: Longman; pp. 28–42

- Lloyd, N. (1925), History of English Brickwork, London: H. Greville Montgomery

![Baroque brick Parish of San Sebastián Mártir, Xoco in Mexico City, was completed in 1663[55]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/70/Capilla_San_Sebasti%C3%A1n_M%C3%A1rtir_a.jpg/80px-Capilla_San_Sebasti%C3%A1n_M%C3%A1rtir_a.jpg)